|

MANZANAR

Historic Resource Study/Special History Study |

|

CHAPTER SIXTEEN:

THE MANZANAR WAR RELOCATION CENTER SITE, NOVEMBER 21, 1945 - PRESENT

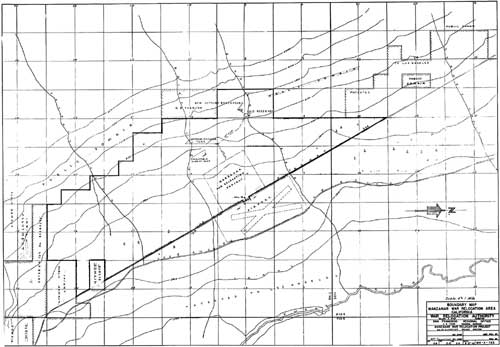

After the last evacuees left Manzanar on November 21, 1945, some War Relocation Authority personnel remained at the site to close out the relocation center's operations. On March 10, 1946, the capital or fixed assets of the former center were turned over to the Department of the Interior's General Land Office (after July 16, 1946, the General Land Office was combined with the Grazing Service under the newly-established Bureau of Land Management) for liquidation, while the center's movable property or consumer/capital goods were assumed by the War Assets Administration for disposal. By 1952 all buildings, except two rock sentry structures at the main entrance and the auditorium which still remain at the site, were removed.

The Manzanar site became the focus of annual pilgrimages in December 1969, and as a result of the efforts of the Los Angeles-based Manzanar Committee the historic significance of the relocation center gained increasing recognition. In January 1972, the California State Department of Parks and Recreation designated Manzanar as a State Historic Landmark. On July 30, 1976, the site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and in 1977 the City of Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Board declared Manzanar a City Historic Landmark. In February 1985, Manzanar was designated as a National Historic Landmark, and on March 3, 1992, President George Bush signed legislation establishing Manzanar as a National Historic Site under the administration of the National Park Service. Planning efforts were soon initiated for management of the site and protection, preservation, and interpretation of its resources for the American public.

WAR RELOCATION AUTHORITY CLOSE-OUT OPERATIONS

National Perspective: 1945-1947

After the relocation centers were vacated, the War Relocation Authority personnel in the Washington office, various other offices, and each of the centers turned their attention to the job of close-out operations. The closure process for the relocation centers consisted of four principal steps: (1) physical clean-up and placement in stand-by condition in preparation for transfer to federal disposal agencies; (2) inventory and declaration as surplus property of all movable and fixed assets of the physical plant for submission to the Surplus Property Board and its successors; (3) termination of operational activity, preparation of final reports, and consolidation of center records for shipment to Washington office for final disposition; and (4) termination of personnel. [1]

The War Relocation Authority had under its jurisdiction approximately $100,000,000 worth of government property By May 26, 1946, all of this had been disposed of except for a small amount of movable property held until June 30 by the Washington office. The $35,000,000 of movable assets had been inventoried and declared surplus. After the various bureaus of the Department of the Interior had selected the items they desired, and a small portion had been turned over to the Federal Public Housing Authority (FPHA) in the Los Angeles area, the remainder was declared surplus to the regional offices of the War Assets Administration (WAA). The $65,000,000 in fixed assets had been declared to the Washington office of the War Assets Administration, which in turn declared them to the disposal agencies of the departments interested.

Jerome, the first relocation center to close, was turned over to the War Department. Two of the relocation centers (Granada and Central Utah) went to the Farm Credit Administration in the Department of Agriculture, and seven (Minidoka, Heart Mountain, Gila River, Colorado River, Manzanar, Rohwer, Tule Lake) to the General Land Office in Department of the Interior. Eventually, Minidoka, Heart Mountain, and Tule Lake were placed under the custody of Interior's Bureau of Reclamation, while Colorado River was placed under the Office of Indian Affairs.

During the final months of the War Relocation Authority, its personnel section assisted employees to locate other employment. Four Civil Service Commission representatives explored openings in different areas of the United States. By June 30, 1946, when the WRA was liquidated by presidential executive order, approximately 3,000 people — all but the 80 employees who would continue with a liquidation unit — had been terminated. By June 1, about 2,200 of the agency's personnel had found employment in other fields. Of this total, the majority transferred to other federal agencies, many going to bureaus and divisions in the Department of the Interior and the National Housing Agency as well as the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration.

In order to carry out the final liquidation of WRA, a "War Agency Liquidation Division" was established under the direction of the Office of the Secretary of the Interior. This division, staffed by about 80 personnel, functioned for about a year after June 30, 1946, liquidating the outstanding obligations of the WRA, completing consolidation of the agency's records and file material for disposal to the National Archives, and completing personnel transactions.

From the outset, the WRA had undertaken efforts to document its program as extensively as possible. It was felt that the agency's program was unique and that complete records of its activities would be of value to government administrators and students in the future. Reports from administrative personnel who had been in charge of activities or programs, together with other file and documentary material, were transferred to the National Archives beginning on June 28, 1945. In addition, a complete duplicate set of the material was transferred to the library at the University of California, Berkeley, while a less complete record was sent by the Berkeley library to the library of the University of California, Los Angeles. A series of monographs and special reports on key phases of the WRA program and statistical records were also prepared by WRA staff members for publication and dissemination. [2]

MANZANAR PERSPECTIVE, NOVEMBER 21, 1945 - MARCH 9, 1946

The WRA continued to administer Manzanar for almost four months after the last evacuee left the camp on November 21, 1945. After conducting its close-out operations, the agency turned over custody of the capital or fixed assets at Manzanar to the General Land Office effective March 10, 1946. [3]

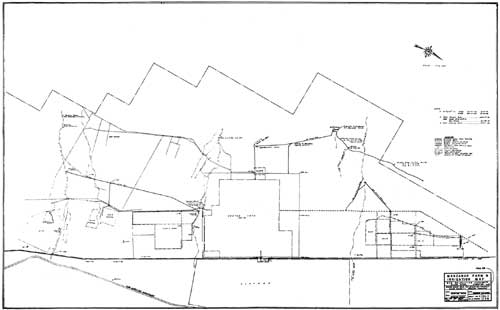

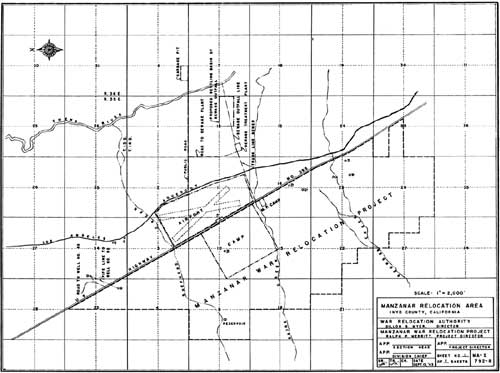

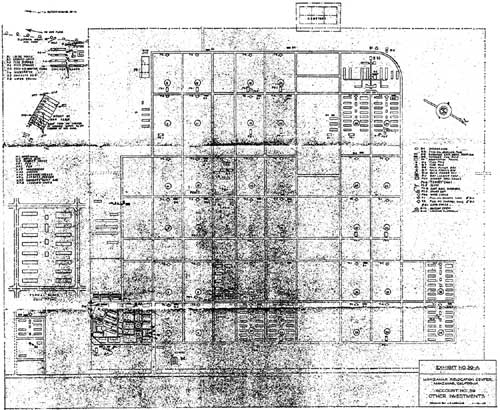

Fixed Asset Inventory

Between August and December, 1945, two specially-trained crews of WRA engineers, accountants, and supply personnel visited each relocation center to conduct a detailed inventory of the physical plant. At Manzanar, the Fixed Asset Inventory was prepared on November 15, 1945, six days before the last evacuee left the camp.The inventory included components relating to six agency control accounts. These were:

Account No. 34— Lands and Farming

Account No. 35 — Buildings

Account No. 36 — Utilities Systems

Account No. 37 — Roads and Bridges

Account No. 38 — Drainage and Irrigation

Account No. 39 — Other Investments (i.e., water stock, hog and poultry plants, processing plants, and miscellaneous items not otherwise covered)

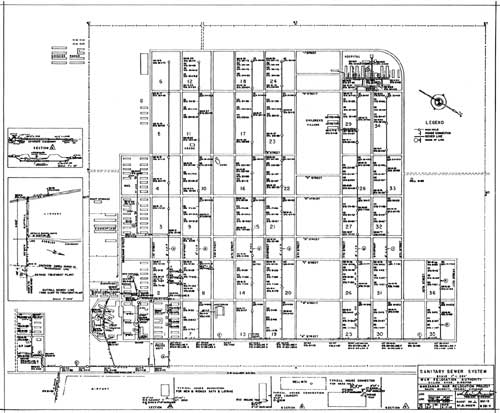

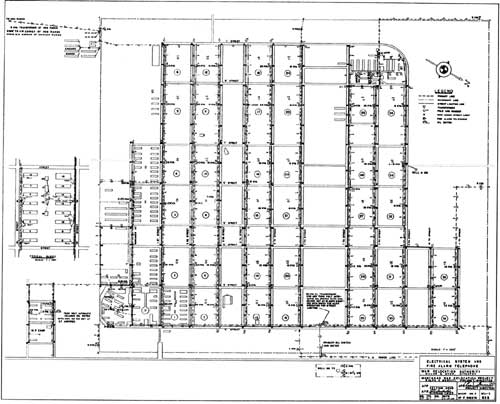

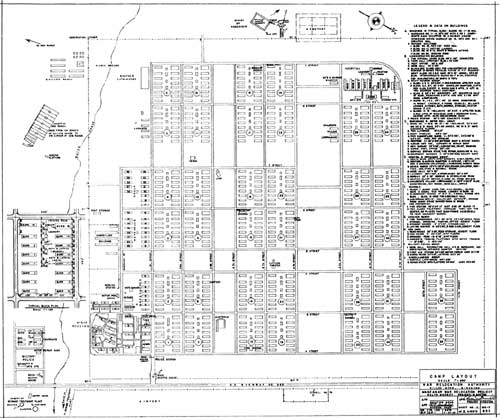

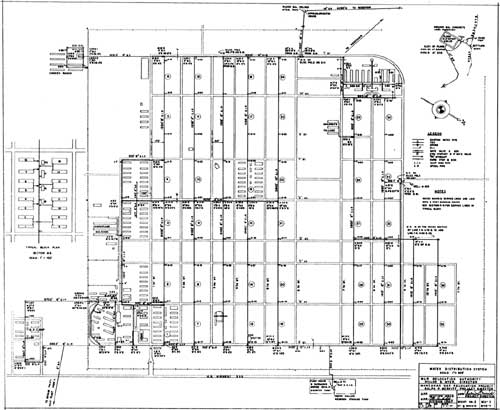

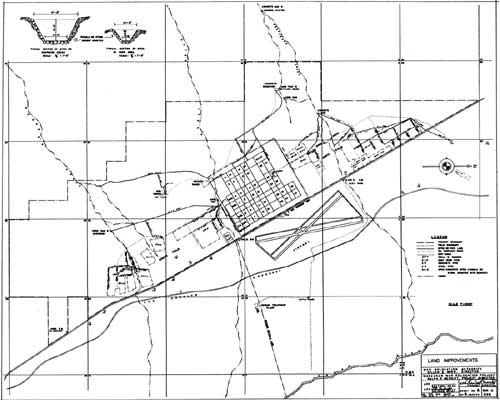

During the inventory process, each element was identified, appraised, recorded by number and check, and reconciled against the account books at the center. Tracings providing details of buildings, utilities, roads and bridges, and drainage and irrigation layouts were prepared.

As shown in the Fixed Asset Inventory, the total appraised value of inventoried items at Manzanar was $2,807,564.28. The original cost of the buildings and utility systems of the camp that had been acquired from the Corps of Engineers was $3,763,441.02, while the estimated cost of WRA additions and new construction was $251,374.27, thus making the estimated total cost of the fixed assets at Manzanar $4,014,815.29.

The inventory team recommended a depreciation of $1,208,427.51, resulting in a net total appraised value of the center's fixed assets of $2,807.564.28. [4]

Surplus Property

From November 21, 1945 to March 9, 1946, the Supply Section at Manzanar was responsible for disposition of all property at the center with the exception of the fixed assets. Early in the spring of 1945, procedures for declaring surplus property were determined "and slowly the writing of declarations began." This particular phase of the program gathered momentum until December 1945." During the next three months, the filing of declarations of surplus property "for all 'major' and 'minor' equipment, materials, and supplies was completed."

Physical inventories of all classes of property at Manzanar were conducted "as soon as released by the using section or unit." After the inventories were completed, all items were classified according to the "Surplus Property Board Manual." A declaration of Surplus Property was made to the disposal agencies on their "forms SPB-1, Declaration of Surplus Personal Property to Disposal Agencies." If and when the disposal agencies certified any items to be "unsaleable," action was initiated so that such property could be removed from property records and placed on the "salvage pile." When disposal agencies sold the property after declaration, the Supply Section delivered the items to the purchaser.

During the process when property was declared to the disposal agencies, it was necessary for Manzanar personnel to work closely with those entities. During early 1945, the disposal agency was known as the Treasury Procurement Surplus Property unit. Later, however, this unit was transferred to the Department of Commerce, thence to the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, and finally to the War Assets Administration. Thus, "the securing and sustaining of necessary cooperation from disposal agencies required considerable ingenuity and effort on the part of the Supply Officer." Despite the efforts of the Supply Officer, the everchanging reorganization of the surplus disposal agencies caused considerable delay and confusion in getting rid of surplus materials at the center.

During late 1945 and early 1946, the Manzanar Supply Section shipped "a great amount of property to the [WRA] Area and Regional Offices for their use in providing temporary housing for relocated evacuees." It also shipped "considerable building material" to various government agencies "for remodeling proposed housing units for relocated evacuees."

In addition, the Manzanar Supply Section conducted sales of surplus property to other bureaus under the Department of the Interior. It sold project-produced goods, surplus subsistence supplies, and salvage materials. [5]

Clean-up Operations

As at other the other relocation centers, the Engineering Section, aided by the Supply Section, undertook the clean-up of the grounds and buildings at Manzanar "for declaration to the Surplus Property Board" after the last evacuees left the camp. [6] As movable property was picked up from the barracks and other vacated structures and removed to warehouses, crews cleaned-up the center and placed it in "a standby condition." Each structure was cleaned and swept out, and the outside area was cleared of litter. Stoves were moved from the barracks to central locations for storage. Windows were shut, and doors were nailed tight. Connections in the water, sewage, and electric systems in the vacated areas of the center were turned off, and a weed eradication program was implemented to reduce the fire hazard. [7]

On November 30, 1945, the Manzanar post office was closed, and the task of distributing the staff's personal mail was added to the duties of the Mail and Files Office. That same day telephone operations were curtailed by closing the center switchboard from 11:30 P.M. to 7:30 A.M. each day. Telephones were removed from all center offices that had discontinued functioning, and dial telephones were placed in the apartments of Project Director Merritt, the fire chief and his assistant, and the Internal Security Office. The lone coin-operated telephone in the center was placed in the rock sentry house at the center's front gate. Telegraph service was discontinued on November 21, and teletype service was discontinued on November 30. [8]

After receiving per mission to dispose of its surplus subsistence, the Mess Hall Section shipped remaining supplies to government agencies and to two private dealers. By January 29, 1946, all except $1,000 worth of foodstuffs had been marketed. [9]

Disposal of Evacuee Property

When the last evacuee departed Manzanar on November 21, approximately "100 family lots of property which had not been picked up were still left in apartments." Immediately, the center's Evacuee Property Section began collecting the lots for storage pending its shipment to the relocated evacuees. The work was completed in approximately two weeks.

The property of the Terminal Island people who had recently left the center as a group, as well as numerous other lots, had not been weighed. After the lots were weighed, letters were sent to Terminal Island evacuees who had goods in project storage beyond the "60-day limit." By January 17, 1946, shipping instructions had been received for all but two of the 73 property lots stored at Manzanar.

At that time, it was estimated that about 30 property lots would have to be shipped to the government warehouse in Los Angeles because of the "inability of their owners to accept them." In addition, there were ten unidentified items (for the most part of no value) and four small lots of property which belonged to deceased evacuees without heirs, which would probably also be shipped to the warehouse before the section closed on February 15. [10]

Relocation Center Cemetery

As the WRA was preparing to close the Manzanar War Relocation Center, WRA officials in the Washington office and at the project discussed the status and disposition of the center's cemetery. On June 6, 1945, John H. Provinse, Chief, Community Management Division, in the Washington office wrote to Project Director Merritt requesting recommendations as to what should be done with the cemetery since "it would appear improbable that any long-time arrangements are possible for care and protection of such cemeteries." "Exhumation, shipment, and reburial at some place chosen by the responsible family relatives" was a possibility. "Cremation after exhumation might be acceptable in many cases." Some burials "without known surviving relatives which if moved at all" would "require reinterment in potters' fields" [11]

In response, Lyle G. Wentner, Assistant Project Director, responded to Provinse on June 27, stating that "the people of Manzanar erected a monument at the approximate cost of $1,000 at the entrance to their cemetery site, which they considered a permanent burial ground." Thus, there was "no reason whatsoever why these people could not stay where they are."

Although the cemetery had reportedly once contained 80 burials, only 15 burials (dates of death ranged from May 16, 1942 to December 19, 1944) remained, four of whom "are without relatives and whose remains would, by law, be put in custody of the county of their residence for disposal." When people died "intestate and the county assumes custody, the remains are disposed of by cremation in all cases." Bodies that were removed from the cemetery "must be shipped by state law" in metal boxes, "which are not obtainable at the present time." The cost of the metal containers was $50, and the cost of paperwork "incident to removal and shipment" was $25. The project management did not "deem it advisable to request local communities to accept remains for burial."

At the present time, according to Wentner, there were only three families "living in Manzanar who are relatives of deceased persons in our cemetery." Four of the deceased people had no relatives. Eight had relatives who had relocated to various places in the United States. Accordingly, Wentner recommended that the WRA write to the relatives informing them that the center was closing and that the agency wished "to respect their wishes if they desire to have deceased relatives removed from the Manzanar Cemetery." [12]

By early January 1946, all but six bodies had been removed from the Manzanar cemetery. On January 7, Project Director Merritt ordered A.M. Sandridge, Senior Engineer - Public Works, to build a "three-wire fence, with posts 4 feet high, around the smallest area of the Manzanar Cemetery necessary to enclose the remaining six graves." The ground "where bodies have been dug and removed" was to be smoothed out. Markers were to be left "only on the six graves in which there are bodies." A two-foot-wide opening in the fence should be provided "for people to enter." The little graves to the north of the cemetery were not to be included as they "are the burying places only of pets." [13]

Labor Needs

After the last evacuees left Manzanar, the center was forced to recruit common laborers, as well as a few skilled workers, to complete the camp's clean-up and close-out operations. Between November 21, 1945, and February 9, 1946, when the center's personnel records were forwarded to the Washington office, the Personnel Section at Manzanar recruited 155 new employees, and separated 74. The recruitment of labor was complicated by the fact that many of the mines and chemical companies in the Owens Valley region were restarting postwar operations, and some companies were offering wages that "were excessive even when compared with wartime wages."

Thus, many of the new employees tended to be itinerant laborers "who were more or less chronic drunkards." [14]

Beginning in October 1945, the appointed staff mess hall at Manzanar was staffed with a crew brought in from Los Angeles. This crew, consisting primarily of former evacuees from other relocation centers, remained at Manzanar until the end of February 1946. [15]

Reductions in Force

Beginning on November 30, 1945, when the first WRA appointed employee at Manzanar was terminated because of a reduction in force, the Personnel Section conducted a survey of permanent employees and remaining work at 15-day intervals. A decision was made concerning which employees in the closing sections could be transferred to sections needing additional help, and termination notices were issued to those employees whose services could not be utilized. Notices were issued 30 days prior to the time that an employee's services were terminated.

Early in November, a representative of the Civil Service Commission visited the center and interviewed every employee who desired to be placed in another federal agency In December, two representatives of the War Relocation Authority in Washington visited Manzanar for the same purpose. Late in January 1946, another representative of the Civil Service Commission interviewed employees for approximately a week relative to future employment opportunities. In addition, Project Director Merritt and other administrators at the camp gave the placement of Manzanar employees priority over all other business. All personnel records were transferred to Washington on February 9, and thereafter the Personnel Office confined itself to advising employees on personnel matters, forwarding personnel information to the Washington office, and placing Manzanar employees in other federal agencies. [16]

Shipment of Files and Records to Washington

The Washington office directed the Statistics Section at Manzanar to collect and forward all essential information concerning the evacuees. When the last evacuee had left, personnel from the Statistics Section joined those in the records unit in the effort to dispose of the center's records, separating the papers which should go to Washington from those which should not. Two former workers in the Relocation Division were also detailed to assist in the work. [17]

Final Report

The last staff meeting was convened by Project Director Merritt at Manzanar on February 15, 1946. On that date, the Final Report, Manzanar, a 5-volume document consisting of nearly 1,600 pages, was submitted to the Washington office. The voluminous report, prepared in compliance with a directive from the Washington office to all relocation centers, featured exhaustive descriptions of the management and accomplishments of each administrative office, division, and section, and thus provides the most comprehensive and detailed history of the operation of the camp. In the first section of the document, entitled "Project Director's Report," Merritt observed:

Thus ends the story of Manzanar as a relocation center. . . . The war-time job of every member of the Manzanar staff ended with credit to themselves and a successful completion of the program laid down for them by the national Director. . . .

Manzanar will return to the desert and be forgotten, but the spirit and achievements of staff and evacuees who here worked together will not die or be forgotten. In these three years and a half, while the world was engaged in its bloodiest war, the people of Manzanar of many national and racial origins, learned by practise [sic] the way of tolerance, understanding, and peace. [18]

LIQUIDATION AND DISPOSAL OF MANZANAR WAR RELOCATION CENTER UNDER GENERAL LAND OFFICE (BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT AFTER JULY 16, 1946) AND WAR ASSETS ADMINISTRATION: MARCH 10, 1946 - APRIL 1, 1947

On March 10, 1946, the capital or fixed assets of the Manzanar War Relocation Center were turned over to the custody of the General Land Office in the Department of the Interior for liquidation, while movable property or consumer and capital goods were assumed by the War Assets Administration for disposal. The functions of General Land Office and the Grazing Service were reorganized and placed under the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) established within the Department of the Interior on July 16, 1946.

Appraisal Report

After the Manzanar War Relocation Center site was turned over to the General Land Office, that bureau sent five field examiners, including Elton M. Hattan, Ernest R. Cushing, J.D.C. Thomas, C.L. Farrar, and Edmund J. Sweeney, from its Branch of Field Examination in Washington to Manzanar to conduct an appraisal of the property. In late April and early May, the field examiners prepared and submitted an "Appraisal Report: Buildings, Improvements, and Designated Personal Property Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California" to the bureau's Washington office.

One section of the report, entitled "Appraisal Report of Buildings and Structures," which reevaluated and revised estimates of the earlier Fixed Asset Inventory, concluded that the cost to the government of buildings and structures at the former relocation center, amounted to $3,999,612.79. The appraised value of the buildings and structures in place was $550,400.77 (less than 20 percent of the total listed in the Fixed Asset Inventory), while their appraised salvage value (taken apart or torn down and removed from the site) was $279,429.87.

In an appended section, entitled "Explanatory Notes," the field examiners reported that the evacuee barracks and recreation buildings could not "be used in place and will have to be moved or torn down to comply with the court order of condemnation which requires that the property be restored to its original owners in its original condition." Accordingly, they determined the value of the buildings based on "the actual value of the material in the building, with no addition for cost of construction, and no deduction for loss of salvage."

Concerning the salvage material in the structures, the field examiners found that the "doors, except as otherwise mentioned, are home-made of scrap lumber and have no salvage value." The windows were generally "in good condition with very few broken panes. Concerning the "dimension lumber", they noted:

The dimension lumber such as 2" x 6" and 2" x 4" pieces can be salvaged and the greater part of the roof sheathing. There will be considerable waste in the flooring and side walls. The evacuees cut extra doors under many of the windows which will reduce the salvage material in the side walls. There is some salvage material in skirting, from the ground up to the floors.

The field examiners noted that the WRA had dismantled three buildings "with much care" using evacuee labor paid at the rate of $16 per month. [19] The amount of usable lumber salvaged was approximately 7,740 board feet. It was not likely, however, that "that amount of lumber can be saved in the course of normal salvage operations." It was estimated that in normal operations "approximately 60% of the lumber and 25% of gypsum board can be salvaged." The labor cost was estimated "from experience of the WRA here at 16 man days at $12 per day, or approximately $192 for dismantling each building." The value in place of each building was $279, thus resulting in a salvage value of only $87.

Similar detailed evaluations of the appraised and salvage value of all buildings and structures in the former center were prepared by the field examiners. In addition to the buildings and structures, the field examiners prepared inventories/appraisals of equipment and furnishings in the auditorium, hospital complex, and appointed personnel quarters, listing the acquisition cost and appraised value for each item. [20]

Maintenance of Site

By May 1946, the General Land Office had established an eight-man maintenance crew at the former Manzanar War Relocation Center under the direction of Clyde F. Bradshaw. Two of the men, George Shepherd and Johnnie T. Shepherd (Johnnie had been employed by the WRA from October 16, 1945 to March 9, 1946), were Paiute Indians living on the tribal reservation near Lone Pine. The Shepherds were general laborers, who mowed the grass and helped on oil, rubbish, and plumbing crews for which they were paid $35 per week. The other members of the maintenance crew included a boiler maintenance man, carpenter, oil and rubbish maintenance man, plumber, general utility and stove maintenance man, and an office man. According to Bradshaw. the maintenance crew "was selected for general ability." All members, "except the Indian laborers," served "in any needed capacity." The water and irrigation systems required "daily attention, frequently at off-schedule hours." Most of the maintenance crew worked "50 to 60 hours weekly. "With a small crew, and work areas spaced as much as six miles apart, such a schedule" was, according to Bradshaw, "almost unavoidable." [21]

Disposal of Buildings, Structures, and Improvements

When the General Land Office assumed custody of the Manzanar War Relocation Center site on March 10, 1946, it acquired the lease to the property that the War Department had obtained from the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California, Northern Division, on June 27, 1942. The lease, which was subsequently declared surplus, provided that 90 days after its termination the buildings and improvements erected by the government at the relocation center were to be removed. The General Land Office believed the removal could be accomplished by mid-September 1946; thus, notice was given that the lease, which expired on June 30, 1946, would not be renewed.

Under the terms of the original lease, the City of Los Angeles had the option of indicating that it wished to acquire the buildings and improvements in lieu of site restoration. Exercising its option, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power had submitted to the Surplus Property Board on November 28, 1945, and January 8, 1946, applications for acquisition of various buildings and facilities in the former relocation center. The General Land Office formally acknowledged these applications on March 3, 1946, in view of its impending takeover of the center for liquidation purposes. Accordingly, on March 8 the department submitted an updated and revised list of "Structures and Equipment at Manzanar Relocation Center Needed By Department of Water and Power." The department offered to purchase "eight apartment and dormitory structures to accommodate eighteen families and five single workmen" in the former WRA appointed personnel housing area, together with their furnishings; the auditorium with its incidental equipment and fixtures; 11 buildings in the hospital complex; the appurtenant water and sewage systems associated with these structures; and the entire electrical power distribution system. Later on March 26, the department indicated that it also wished to purchase the laundry building in the former appointed personnel housing area. These requests were formalized by a court stipulation on March 27, 1946, serving notice that these buildings and utility systems were not to removed.

The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power considered a wide range of uses for the buildings and improvements in the former relocation center that it wished to purchase. In terms of the hospital structures, the department considered operating the facility for the benefit of its Owens Valley employees and their families as well as any private patients who might desire medical service; leasing the facilities to a private doctor or group of doctors or to a community hospital district which might be formed to include the Manzanar area; and selling the medical equipment to Bishop Community Hospital. As for the auditorium, the department intended to interest local organizations in purchasing the building and leasing a small parcel of acreage on which it stood. In terms of the former WRA appointed personnel housing, the department considered renting the structures to employees, as well as non-department people, to meet the postwar housing shortage. Two dormitories might be moved to Mojave where facilities for single employees were needed. The department's power system branch might find several structures useful for removal to station locations for employee housing. [22]

During May 1946, the Federal Public Housing Administration informally arranged to convey eight structures in the former WRA appointed personnel housing area at Manzanar to the Inyo County Housing Commission for emergency housing for veterans, and the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power informally agreed to lease to the Housing Commission for a five-year period a 19-acre parcel of land upon which the structures were located. The negotiations were conducted with the understanding that employees of the department who had served in World War II would be permitted to occupy some of the quarters and that the structures would revert back to the department at the end of the lease. Since the structures which the FPHA proposed to convey to the Housing Commission were among those requested earlier by the department, the General Land Office would not authorize such conveyance until the LADWP withdrew its application. Thus, the department on June 7, 1946, withdrew its application for the eight apartment dormitory buildings designated G, H, L, M, N, O, P, Q. [23]

In addition to the LADWP, agencies in the Department of the Interior and other public entities also indicated interest in acquisition of buildings or equipment at Manzanar during late 1945 and early 1946. For instance, the furnishings in the former WRA appointed personnel housing units were earmarked for the U.S. Indian Service, while the hospital laundry equipment was designated for delivery to the National Park Service. The Owens Valley Unified School District wanted two "caucasian housing units" for transfer to Independence to meet urgent teacher housing shortage needs. [24]

During the period from late March to mid-May 1946, Ralph Merritt, the former WRA project director who had become the War Assets Administration field representative at the site, pressed the LADWP for "a five-year lease on certain acreage and facilities within the present fenced area of the Manzanar Center." On March 26, he informed LADWP officials that he had lived in Owens Valley for 12 years. Thus it was "natural that I have a strong attachment for the place and should desire to remain" and "to secure a place of living and activity for myself and family" He continued:

The Board does not desire to create a new town in the Valley but at the same time has publicly stated its purpose to obtain and maintain certain facilities now at Manzanar. Board employees, school teachers in near by towns, employees of the State and County, veterans and other residents are in urgent need of housing facilities at this time. Conditions five years from now may be much different but no housing now available should be destroyed or removed. It would appear to be sound policy to permit a five year lease holder to operate the staff housing group of buildings consisting of 22 buildings containing apartments and single rooms, the administration building converted into a social center, the mess hall (of operation is needed and profitable), the reefer building and one warehouse, a total of 26 buildings with all present furnishings and equipment oil storage tanks and water sewage and electrical connecting lines. The lessee should be permitted to use water for lawns and dust control without added charge but should pay on scheduled rates for domestic water and lights and power used. Rates for rentals to department employees and the number of employees to be housed should be approved by the Board.

In addition to the housing area I desire the use of approximately 20 acres in the north west corner of the Center. I propose to buy from whosoever purchases the barrack area of the Center from the Government. The hospital buildings, children's village or blocks 29 and 34 together with water, sewer and electrical lines. This would be used as a tourist and recreational center. Because of the gardens now in this area and the adaptability of the buildings little new capital would be required for a tourist center of about 50 units. Because so little capital is needed for construction the lease might require that I clear the site in five years. Approximately 10 of the 20 acres might be used for agriculture and the lease might be based on such charges as are established.

I also wish to use the bath house and 3 acres of herb garden. . . [25]

On May 9, Merritt, although aware of the negotiations among the FPHA, Inyo County Housing Commission, and LADWP, again wrote to Department of Water and Power officials, reminding them of his request for a five-year lease. He observed that he desired the appointed personnel housing area at Manzanar to provide employment for his son Peter, who had been working with the Curry Company in Yosemite National Park and had "valuable experience in activities of that nature." He also desired to lease a small area in the vicinity of the hospital to establish "a semi-recreational and tourist facility, taking advantage of the approximately $5,000 worth of roses and other shrubs that the Japanese had left there." [26]

After rejecting the LADWP purchase offer because of the difficulties inherent in selling scattered buildings and utility system segments at the former relocation center, the General Land Office determined to offer the buildings and improvements at Manzanar under the provisions of the Surplus Property Act of October 3, 1944. Notices of sale were published in the Inyo Independent on June 14 and the Los Angeles Times on June 15. In addition notices were sent to 82 private individuals, 23 government agencies, and the State of California, all of whom had previously indicated interest in acquiring buildings or improvements at the former relocation center.

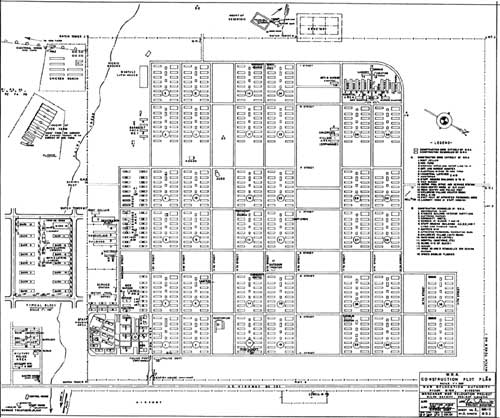

The notice of sale, entitled "Invitation For Offers and Terms and Conditions of Sale of Buildings and Improvements at Manzanar War Relocation Project, June 14, 1946," provided that offers would be received on or after June 14 at the office of the project representative, Joseph H. Favorite, Regional Field Examiner, General Land Office in San Francisco. The purchaser would assume all necessary expenses in "taking down and replacing telephone, electric, and other wires, fences, which may obstruct removal of buildings or improvements and pay all necessary costs in connection therewith." The purchaser would assume responsibility for "the care and protection of the buildings or improvements purchased by him and will be required to remove completely the buildings or improvements covered by the offer, including smoke stacks, chimneys and fireplaces, and clean up the site of the buildings or the improvements to the satisfaction of the Commissioner of the General Land Office or a representative designated by him." Work hours were limited to week days between 8:00 A. M. and 5:00 P.M. The purchaser was required "to fill any post holes under said buildings or excavations necessary for the removal of improvements, to cap all water, gas and sewer lines extending above the ground, to disconnect electric and telephone lines and to make other restorations deemed necessary. The buildings and clean-up operations were to be completed by September 27, 1946. The notice of sale included descriptions of 15 "sales units:"

1. 36 evacuee block units

2. One hospital area unit

3. One warehouse area unit

4. One garage area unit

5. One administration area unit

6. One camouflage area unit

7. One high school area unit

8. One staff housing area unit

9. One Miscellaneous Unit No. 1 (Assorted Buildings in Military Area, etc.)

10. One Miscellaneous Unit No. 2 (Fence and Pipe)

11. One Miscellaneous Unit No. 3 (Poultry and Hog Ranches)

12. One sewer system unit

13. One water system unit

14. One electric system unit 15. One fuel system unit [27]

Following publication of the notice of sale, many inquiries were received by the General Land Office project representatives at the site, but only 19 firm offers materialized, Of these, only ten were acceptable. Offers that were rejected included those for which bids were less than 75 percent of the appraised price of the "sales unit." Under government regulations, such offers were submitted to the War Assets Administration which rejected them. Several interested persons failed to make offers, because the "sales units" in which the property was offered were too small. For instance, some persons and companies interested in large-scale salvage operations were only interested in making offers to purchase all of the buildings and improvements in the former relocation center. In response to critics, however, Secretary of the Interior Julius A. Krug defended the terms of the sale, stating that under government regulations the General Land Office had been required to establish "sales units" that would be attractive to persons for small business, residential, or agricultural purposes. The regulations also stipulated that priorities would be given to war veterans to purchase single buildings, as well as to federal, state, and local governments and their instrumentalities and non-profit institutions. The General Land Office, according to Krug, was not authorized to sell the project as a whole since such action would have created an opportunity to large salvage companies to obtain control of the project and thus deny individuals and small businessmen a chance to acquire some of the property.

While the notice of sale provided that after 10 days from the date of the publication the property at Manzanar might be disposed of "by transfer of responsibility of demolition and disposal to the disposal agency designated to perform demolition functions," the General Land Office, and its successor the Bureau of Land Management, permitted an additional period of time to persons who might wish to make offers for the property. The transfer for demolition was sought by the War Assets Administration in order to provide materials for the "HH" program of the National Housing Agency. This program was designed to make available from temporary wartime camps and other emergency installations the materials that were sorely needed to construct housing for war veterans. Accordingly, on July 18, when it became apparent that not enough offers would be received to permit disposal of the project within a reasonable time, the former relocation center was transferred by the Bureau of Land Management to the War Assets Administration for demolition. Excepted from this transfer were 22 buildings in the former WRA appointed personnel housing area, along with their furnishings/facilities and appurtenant utility systems, that were conveyed to the Federal Public Housing Authority for transfer to the Inyo County Housing Commission to establish a war veterans' housing area known as the "Manzanar Housing Project." In addition, those buildings which were in the process of sale to the 'aforementioned ten successful bidders were also excepted from the transfer to the War Assets Administration. Arrangements for completion of the demolition work at Manzanar were assigned to the WAA and the Corps of Engineers. [28]

During the summer and early autumn of 1946, more than 90 buildings were sold, dismantled, and removed from the site of the former relocation center. These structures included: Block 1, Building 5; Block 2, 20 buildings; Block 7, 20 buildings; Block 8, 20 buildings; Block 18, 20 buildings; Block 36, Buildings 11 and 13; Garage Area, nine buildings; Hospital Area, Doctors' and Nurses' Quarters; Children's Village, Building 3. Virtually all of this demolition work was conducted during August, September, and October, and most was completed by mid-October. [29]

Leland R. Abel, John C. Ellis, and J.W. Newton, all of Laton, California, were the successful bidders for purchase, dismantling, and removal of all the buildings in Blocks 7, 8, and 2, respectively. The three men were farmers, although Newton also owned the Laton Lumber Company. They received permission to live in the laundry room of Block 7 while they dismantled their purchased buildings, because they claimed they could not afford to stay in area hotels for several weeks. In return for this privilege, they agreed to obey the "fire rules" and stay within the area of the buildings they were removing. They set up a butane stove in the laundry room, which also served as their sleeping quarters and mess. Newton subcontracted with R. J. Roulet, a building contractor and house mover from Bishop, to move four barracks from Block 2 to Olancha. Ellis sold at least one building to a Mr. Garretson at Wasco who used the salvaged materials for domestic uses in his community. A considerable amount of the salvaged materials from Blocks 2, 7, and 8 were used for repair and construction of residential and ranch buildings in Laton.

Telly C. Imus, the purchaser of 20 buildings in Block 18, used the salvaged materials from his structures for repair and construction of residences in Lone Pine and his home community of Big Pine.Isadore Lindenbaum of Los Angeles purchased nine buildings in the garage unit area. Perhaps because of the distance from his home to Manzanar, he subcontracted with Paul M. Hurst and Robert Blair to dismantle and remove the buildings. The contract, however, did not include equipment, tools, or supplies in the buildings, and officials with the Bureau of Land Management took care to ensure that these items were not removed from the site. [30]

Nina Taylor, a member of the Ezra Taylor family that had moved to the Manzanar community in 1927, later wrote that her Aunt Anna Taylor had given her "three lots on the corner of East Post and South Mt. Whitney Drive" in Lone Pine. After one of the houses from the relocation center was moved to her property, she had new roofing installed and added windows and screen doors. The exterior, as well as the interior, was refurbished with a new finish and painting. [31]

Meanwhile, negotiations with the Federal Public Housing Authority had continued throughout the late spring and summer of 1946 as federal housing officials attempted to meet the nationwide housing shortage facing returning war veterans. By late August 1946, a total of 36 buildings at Manzanar had been transferred to the FPHA to help meet these needs. Of this total, 25 were used on site for the aforementioned "Manzanar Housing Project," and 11 were removed off-site. On May 24, 1946, eight buildings in the military group area — Building No. l. Administrative Building; Building No. 2, Recreation Hall; Building No. 3, Mess Hall; Building No. 4, Officers' Quarters; Buildings Nos. 6, 7, 8, 9, Barracks — were conveyed for off-site transfer. On June 19, 25 buildings in the former WRA administration and appointed personnel housing areas, along with their furnishings and utility systems, were conveyed for use on site. Twenty-two of these buildings were in the former appointed personnel area: Dormitory Buildings A, B, C; Family Apartments E and F; Personnel Apartments G, H, I, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, U, V, and W. Three of these buildings were in the former relocation center administrative area: Administration Building No. 1; Provost Town Hall, Building No. 4; and Personnel Mess Hall, Building No. 6. On July 13, two additional buildings in the military area — Building No. 10, First Aid Building, and Building No. 11, Bath House — were transferred to the FPHA for removal off-site. On August 29, a final building in the military area — Building No. 12 — was transferred for removal off-site. [32]

During the summer of 1946, the War Assets Administration took steps to demolish all of the buildings and improvements at the former relocation center that had not been transferred to the FPHA or sold, dismantled, and removed from the site. On August 9, John J. O'Brien, Deputy Administrator of the WAA Office of Real Property Disposal, informed the Corps of Engineers that pursuant to a directive prepared on June 20 by Wilson W. Wyatt, a WAA Housing Expediter, the Corps was directed to proceed with the preparation of a plan and specifications for negotiation of a contract to demolish approximately 742 buildings on the site of the former relocation center. The government's lease of the land for the center, which had expired on June 30, provided that the site be cleared and restored to its original condition by September 30. Thus, the specifications should cover (1) complete dismantlement of all structures; (2) salvage of all usable materials, equipment, and assemblies; (3) stockpiling of all salvaged items onsite with provision for adequate protection from the weather; (5) removal from the site of all materials, equipment, and assemblies which were determined not to be usable; (6) and retention by the government of title to all usable materials, equipment, and assemblies; and (7) complete inventory of all recovered materials, equipment, and assemblies.

On August 26, Cecil L. deWolfe, the WAA Deputy Regional Director for Real Property Disposal in Los Angeles, forwarded to the District Engineer of the U.S. Engineer's Office in Los Angeles a detailed list of the buildings and miscellaneous structures to be dismantled and removed from the site. Accompanying the list, entitled "Units To Be Dismantled, Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, Calif., Directive Consecutive No. 7-D-28, Job No. Manzanar ESA 7-299-0," were directions from deWolfe regarding restoration of the site, The restoration work would include removal of concrete slabs, foundations, curbs, piers, or structures that extended above normal ground surface. These materials were to be broken up and buried under "not less than 30 inches of earth cover leaving surface so as to conform with surrounding terrain" or by hauling them "to [the] dump site on government land westerly of the camp for disposal.' Cellar excavations and other "unnatural depressions" were to be backfilled "to conform with normal ground surface." Fences were to be restored to their "original condition and locations as indicated by [a] Department of Water and Power representative." Debris or scrap lumber was to include 'gathering, burning, and burial of ashes with not less than one foot of earth cover leaving surface level with surrounding terrain." Noncombustible material was to be disposed of in a manner similar to that for "broken concrete." Cleaning up would include "raking and hauling to [the] dump site all refuse or debris remaining after completion of dismantlement and/or restoration operations." Removal of utility systems and roadways in the camp area and concrete-lined ditches, pipe lines and irrigation structures in the agricultural areas would not "be necessary.' "Concrete slabs located at the swine farm and chicken ranch, excepting those portions extending above normal ground. may be left undisturbed." "Rock walls and borders along roadways and paths, particularly in the hospital area, may be left in place" [33]

As initial demolition procedures at Manzanar got underway, Congressman Clair Engle and Senator William F. Knowland appealed to the WAA to sell the auditorium to the Turner Barnes Post No. 8036, Veterans of Foreign Wars of Inyo County, for use as a clubhouse and meeting hall. Accordingly, Paul C. Williams, Director of the WAA's Urban & Rural Division, Office of Real Property Disposal, authorized deWolfe on September 4 to withdraw the auditorium from demolition temporarily and dispose of it to a local governmental agency that would handle its conveyance to the Veterans of Foreign Wars for its salvage value rather than its appraisal value. Disposal to a local governmental agency was subject to certain conditions:

. . . . demolition of the building could not be delayed beyond the point at which it might delay the entire program, since the United States are obligated to vacate the property by September 30, 1946.

The purchaser of the building must assume all obligation of the United States to restore the land upon which the building stands. Or if arrangements have been made with the City of Los Angeles, as lessor, for the purchase to leave the building on its present site, the City as lessor, must release the United States from its obligation to restore that portion of the installation upon which the building is located. In view of the terms of the lease between the United States and the City of Los Angeles, disposal of the building can be made only on condition that it be removed.

The purchaser should further be advised that the United States can grant him entry to the property and access to the building only until September 30, 1946. . . . . the purchaser must be charged a price equal to the current market value of the property. [34]

During the spring of 1947, the auditorium was sold to Inyo County and a 10-acre "strip of land 320 feet in width extending 1445 feet westerly of the State Highway" on which the building was located was leased to the county The west boundary of the parcel extended "only a short distance beyond the auditorium sufficient to include a paved street and a fire hydrant." Because the auditorium was located approximately one-quarter mile from the state highway and "it would be impossible to move the large structure for a reasonable cost, the majority of the acreage involved" was located "between the auditorium and the State Highway." This area constituted "an ideal parking location for automobiles and would not be particularly useful to the Department without the expense of fencing same on an irregular boundary." [35]

Demolition and removal of the buildings and improvements at Manzanar proceeded slowly during the autumn of 1946 under a contract let to J. F. Combings of Burbank, California. On December 2, 1946, the Los Angeles Times reported that except "for a few staff buildings left standing the war-born town of Manzanar which housed 10,000 Japanese internees today is flatter than Hiroshima." The "once-teeming relocation center" had been "hauled away piecemeal, in trucks." Observing that veterans "got a break," the newspaper noted that a veteran only needed his discharge as a "priority" to purchase a "20 x 100-foot barracks for $333.13, including tax." For his money, he got "8000 square feet of seasoned pine and redwood lumber, 1000 square feet of wallboard, 22 slide windows, four interior doors, 200 feet of wiring and six electrical outlets." Erwood P. Elden, a "Glendale architect and former major in the Army combat engineers," had drawn up four floor plans, any one of which can be built from the materials salvaged from a barracks."

The newspaper praised Ralph Merritt who had become the WAA field representative at Manzanar. Under Merritt's direction, "750,000 board feet of lumber and 600,000 square feet of salvaged wallboard have been redistributed in this neck of the woods." During a special sale that had been arranged at the urging of Merritt from November 15-27, veterans from Bishop had purchased 52 barracks, while those from Lone Pine had bought 32. Veterans from Independence had purchased 28, Inyo-Kern 27, Ridgecrest 20, Bridgeport 12, and Los Angeles 12.

According to the newspaper, a typical purchaser at the sale was Joseph Guzman, an ex Army infantryman who supported his wife and two children by working in a talc mill. They were renting quarters in Keeler, but would soon move into their three bedroom house at Lone Pine, "just as soon as Guzman finds time to build it with his $333.13 worth of materials." Another veteran from Norwalk, a suburb of Los Angeles, purchased one entire ward of the Manzanar Hospital, the materials from which he intended to use for construction of a four-family apartment house.

Federal agencies had also taken advantage of the special November sale. The Birmingham Veterans Hospital near Van Nuys in the San Fernando Valley purchased quantities of "scarce items" such "as plumbing, medical supplies and lumber." Plumbing supplies and lumber were sent to the Veterans Hospital at Sawtelle in the West Los Angeles area. Nearly half of the salvaged materials from the camp were "redistributed" to the Federal Public Housing Administration for veterans' housing projects in Bishop, southern California, Utah, and Arizona. Citizens in the northern part of Inyo County organized the Inyo County Hospital Association and equipped a "modern hospital at Bishop with $14,000 in supplies" — the estimated value of the supplies was $60,000.

Although much of the former Manzanar War Relocation Center site looked "like it had been the target of an atomic bomb," some buildings remained. Inyo County had purchased the auditorium and planned to convey it to the veterans for use as a social center. Thirty families were living in the former WRA appointed personnel quarters, and 30 more families would soon move in. [36]

On December 6, 1946, the Inyo Register published an editorial that praised Merritt for "re distributing" Manzanar for the benefit of "Inyo-Mono veterans and organizations." The

last-minute 'redistribution' benefits accruing to this area just didn't happen. They were planned. The pleasing of veterans with 'no red tape' purchases of building materials was the work of Mr. Merritt, who was successful in arranging the new type sale with WAA officials.

In addition to many of the items featured in the aforementioned Los Angeles Times article, this editorial noted that fire fighting equipment and a fire truck from the former relocation center were "being provided the City of Bishop through a negotiated sale." The Arizona State Hospital had been equipped with "a modern hospital, laundry and steam plant" from Manzanar. The Corps of Engineers had purchased and shipped overseas the center's modern sewage disposal plant. Schools, organizations, parks, cemeteries, and other groups in Inyo County had obtained plants and shrubbery. The article concluded: "As we wave goodbye to Manzanar Relocation Center, it's well to know that Owens Valley and its citizens have benefitted so handsomely in the overall picture. [37]

In January 1947 nine WAA officials investigated the progress of the demolition project at Manzanar. They found that 98 percent of the buildings had been demolished, and that 92 percent of the site's clean-up was complete. The demolition work had taken longer than expected, and thus the lease of the property had been extended. However, the demolition work was conducted "in an excellent manner" by J.F. Combings. The area engineer had originally estimated that the demolition contract would cost $650,000, but the actual cost of the contract had only amounted to approximately $450,000. As of January 16, only 12 buildings remained to be demolished. They were currently used to house the demolition contractor's personnel. Approximately 90 percent of the camp's building materials had been made available for salvage, and about 90 percent had been removed from the premises. The remainder would be delivered within ten days.

All told, cash sales of building materials from November 14 to December 4 had been $130,000, while the market value of lumber, plumbing, and electrical supplies transferred to the Federal Public Housing Authority and Veterans Administration from 16 blocks and the hospital and camouflage buildings was approximately $150,000. The WAA had realized approximately $14,000 from the sale of the steam plant, laundry, morgue, and sprinkler system to Arizona State Hospital; $6,000 from sale of the auditorium to Inyo County; $12,500 from building sales of the General Land Office between June 14 and July 16; $34,000 from transfer of buildings to FPHA for veterans' housing; $35,000 from transfer of electrical, sewer, and water system components for service to the auditorium and the FPHA veterans' housing project; and $30,000 from salvage and transfer of electrical distributing system components by Schurr & Finlay Electric, a firm in Hawthorne, California, to the FPHA for Los Angeles Housing Authority. The net value of inventory on hand at the site, which included deep well pumps and motors, water pipe lines, lumber, and elements of the sewage disposal plant, electrical system, and oil distribution system, was approximately $52,000. [38]

Costs for restoration of the Manzanar site were held to the "barest minimum" as a result of cooperative efforts by Merritt and WAA officials and officials representing the City of Los Angeles. Subsequent to negotiations between the WAA and the City of Los Angeles, the latter accepted various improvements at the site in lieu of a complete restoration of the premises: (1) water supply system unit (including one concrete reservoir, one 90,000-gallon steel storage tank, two frame buildings at the reservoir, and iron, steel, and pipe appurtenant to the system, excluding water system components transferred to the FPHA; (2) electric system unit, including poles, cross-arms, transformers, insulators, wire, guy wires, but excluding elements transferred to the FPHA; (3) sewage system unit, including the reinforced tank of the treatment plant, together with the two frame control and chlorinator houses, vitrified clay pipe, sewer piping throughout the camp, manholes, manhole covers and facilities appurtenant to the system, but excluding the elements transferred to FPHA; (4) approximately four miles of barbed wire fencing; (5) two frame houses at the hog and chicken farms; (6) staff housing, public utilities, and the auditorium which were transferred to the FPHA for lease to Inyo County; (7) 15 miles of oiled roadways; (8) concrete-lined ditches and channels; (9) concrete slabs that did not extend above normal ground level, including those at hog and chicken ranches and rock walls/borders, especially those in the hospital and Children's Village areas and the entrance to the military compound; and (10) trees and shrubs. [39]

As a result of negotiations in March 1947, the City of Los Angeles and the WAA agreed that the salvage value of the aforementioned components of the utility systems at Manzanar was $12,203. The estimated cost of the Site's total restoration was approximately $71,759, while restoration that had already been conducted amounted to $7,217. Thus, the transfer of the utility system components, together with other items such as piers, slabs, rock walls, foundation curbs, roads/streets, and fencing which had no salvage value, would result in savings of approximately $54,693 to the federal government. The agreement was formally confirmed by court stipulation on April 2, 1947. On the previous day, the former Manzanar War Relocation Center site formally reverted back to the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power via court stipulation. [40]

Disposal of Agricultural Crops

On July 17, 1946, Elton M. Hattan, a Bureau of Land Management field examiner, informed Tom Silvius, an employee of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power at Independence, that the "alfalfa hay crop" at Manzanar now belonged to the City of Los Angeles. Rattan had been informed by an official in the BLM regional office in San Francisco that we cannot "sell the hay or any of the other things, such as the fruit crops." The official felt "badly about this because it" seemed "certain that the City" could not "take possession of the entire area until we are through with it." Accordingly, Hattan was told that "we should stop spending our time and money in growing crops for the City of Los Angeles." If they "are going to get the benefit from the hay why shouldn't they have some one come in there and irrigate it?" [41]

MANZANAR SITE, 1947-1960s

During the postwar years, the City of Los Angeles leased much of the acreage of the former relocation center site at Manzanar to local ranchers for grazing purposes. This activity would constitute the primary use of the land for the next several decades. [42]

During the postwar years, veterans as well as Los Angeles Department of Water and Power employees, continued to live in the Manzanar Housing Project in the former WRA appointed personnel housing area in the southeast corner of the one-time relocation center site. In August 1948, 126 persons were reportedly living in the project. [43]

In 1951, the housing project at Manzanar was terminated, and the buildings reverted back to the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. The department's records indicate that the vacant buildings were subjected to looting late in 1951. Accordingly, on March 15, 1952, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power held a public auction on the site for the sale and removal of the 26 buildings that had constituted the Manzanar Housing Project. The terms of the sale stated that the buildings were to be reduced "to parts not greater than flat panels" before removal from the site unless exceptions were authorized. Despite the sale terms, however, not all structures were reduced to "flat panels," because some are still in use throughout the Owens Valley today as dwellings and businesses. [44]

The auditorium was leased by Inyo County to the Veterans of Foreign Wars until November 5, 1951. Although the date is not definitely known, it is likely that a wing of the building was moved to Lone Pine for use as a hall by the Veterans of Foreign Wars prior to termination of the lease. Soon thereafter, the Inyo County Roads Department converted the auditorium for use as a garage to service its vehicles. The building would continue to be used as a garage by the department until 1995. [45]

On December 3, 1954, Mary F. Dean, leaser of the Goodale Ranch in Independence, was given permission by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power to remove approximately 250 feet of 2-inch and 3-inch pipe from the ground to make repairs to the domestic water system on her ranch. The work was to be completed by January 31, 1955, the ground and ditches at Manzanar were to be left in a safe and satisfactory condition, and debris was to be cleared away. [46]

MANZANAR AIRPORT, 1956 - 1972

In 1941 the City of Los Angeles leased to Inyo County 619 acres of Department of Water and Power Land on the east side of the highway at Manzanar for airport construction. The 50-year lease, which was never recorded in the county records, provided that rental of the land would be equal to taxes and 50 percent of net profits. A provision in the lease provided that the instrument would terminate automatically should the land not be used for airport purposes for more than one year. The lease also provided that if the lease was terminated as a result of default by the county, the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) could take over for the remainder of the term if it desired. On May 24, 1956, Inyo County notified the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power that it had abandoned the airport, that the CAA had consented to such abandonment and was not interested in the site, that the premises had not been used for airport purposes for more than one year, and that the county would regard the lease terminated as of July 1, 1956. In connection with the lease cancellation the county marked off the runways on July 18, 1956, and the wind sock and tower were removed on January 8, 1957. The Corps of Engineers indicated that it had no further interest in the airport on December 17, 1956. Later on July 7, 1958, LADWP employees removed electrical equipment, including the obstruction lights, arms, conduit, and wires for obstruction lights, for storage in the department's "Independence Warehouse." [47]

Thereafter, the land on which the former Manzanar airport had been located, was leased to local ranchers for grazing purposes and used for a variety of special events. From August 14 to September 1, 1957, the airport was used as a bivouac area for an advance party of the Nevada National Guard. Permission was granted to the State of California's Department of Fish and Game to use the land for coordination of an elk hunt during October 1969. During the period from October 30,1968, to February 1, 1969, Aerojet General of Downey, California, was granted permission to use the land and runways for experimental tests. During April 24-25, 1971, the airstrip was used for the First Annual Lone Pine-Manzanar Time Trials of the Clippinger-Corvair-Corvette Camaro Club. The event was hosted by the Lone Pine Chamber of Commerce, Lions Club, and various area veterans organizations. The "Second Annual Lone Pine Time Trials" were held at the former airport on May 13-14, 1972. Later that spring and summer, the High Sierra Timing Association of Bishop held drag race meets at the former airport on June 4, July 9, August 6, and September 3. [48]

INCREASING RECOGNITION OF HISTORIC SIGNIFICANCE OF MANZANAR, 1969-1992

In response to the rising movement for ethnic identification and sensitivity on college and university campuses during the late 1960s, a group of Los Angeles-based college students organized a pilgrimage to Manzanar in late December 1969. According to one writer, most of the 250 participants were "Asian students who were curious about the camp and unable to get their parents to talk about life there." [49] As a result of the renewed interest in Manzanar, the Manzanar Committee was soon established under the leadership of Sue Kunitomi Embrey, a Los Angeles school teacher who had been evacuated to Manzanar as an 18-year-old high school graduate on May 9, 1942. She had resided in the relocation center until October 6, 1943, when she relocated to Madison, Wisconsin, under the sponsorship of the YWCA. While at Manzanar, Embrey had helped the Maryknoll Sisters to organize a school in the center, worked in the camouflage net factory, and served as a roving reporter and later as managing editor of the Manzanar Free Press. [50]

When it was established, the Manzanar Committee had a two-fold purpose — public education concerning the historic significance of the Manzanar site and establishment of Manzanar as a state historic landmark. Annual pilgrimages to the Manzanar site have continued to be sponsored by the committee to the present time (since 1973 the pilgrimages have generally taken place on the last Saturday of April). Each pilgrimage has featured a commemorative ceremony at the Manzanar Cemetery, followed by a picnic and clean-up efforts at the site. [51]

In late 1971 the Manzanar Committee applied to the California State Department of Parks and Recreation to declare Manzanar as a state historic site, noting that the site "recreates" for many Japanese Americans "that moment in their lives when all the world was enclosed within this one-mile square." In January 1972, the Department of Parks and Recreation designated Manzanar as California Registered Historic Landmark No. 850, and a 4.33-acre area, including the two rock sentry houses at the entrance to the former relocation center in addition to the cemetery and adjacent parking area, were leased by the LADWP to the Manzanar Committee and the Japanese American Citizens League for the historical landmark. [52]

During ceremonies attended by some 1,500 people at the fourth pilgrimage on April 14, 1973, a plaque was placed on the rock sentry house nearest the highway by the State Department of Parks and Recreation in cooperation with the Manzanar Committee and the Japanese American Citizens League. The plaque was installed by Ryozo F. Kado, an 83-year-old Issei who as an evacuee resident at Manzanar had supervised the two rock sentry houses and cemetery monument. For the occasion, Kado reassembled his seven-man evacuee crew.

The Manzanar Committee's fourth pilgrimage and the ceremonies associated with the installation of the plaque were significant in that they "represented the culmination" of more than a year of heated "negotiations with the State Department of Recreation and Parks." The negotiations had involved "torrid controversies over whether such terms as 'concentration camps' and 'racism' ought to be engraved on the plaque which was to make Manzanar a California Historical Landmark." On three occasions, representatives of the Manzanar Committee and the Japanese American Citizens League traveled to Sacramento in an attempt to get their wording accepted by state officials. After the state found other words, such as "hysteria" and "greed," objectionable, the Manzanar Committee enlisted "community support" in "the form of letters and petitions." State Assemblymen Alex Garcia, whose district included "Little Tokyo," Ralph Dillis, whose Gardena district included many Japanese Americans, State Senator Mervyn Dymally of Los Angeles, and Assembly Speaker Robert Moretti entered the fray on the side of the Japanese American groups. After a stormy 90-minute confrontation with William Penn Mott, the Director of the state Department of Parks and Recreation who would later become Director of the National Park Service, a compromise was worked out. Under its terms, the state would write the first paragraph on the plaque. The second paragraph, to be written by the Manzanar Committee and the Japanese American Citizens League, declared Manzanar to be the first of 10 such concentration camps confining 10,000 persons bounded within barbed wire and guard towers. The third paragraph incorporated compromise language, allowing the state to include wartime "hysteria" as a contributing element to the government's evacuation program and the Japanese to blame evacuation and relocation on "racism and economic exploitation." The final wording of the plaque, which would continue to remain the focus of controversy, stated:

In the early part of World War II, 110,000 persons of Japanese ancestry were interned in relocation centers by Executive Order No. 9066, issued on February 19, 1942.

Manzanar, the first of ten such concentration camps, was bounded by barbed wire and guard towers, confining 10,000 persons, the majority being American citizens.

May the injustices and humiliation suffered here as a result of hysteria, racism and economic exploitation never emerge again. [53]

In 1974 the California Assembly passed House Resolution No. 135 directing the state Department of Parks and Recreation to study the feasibility of acquiring and developing a plan "for the acquisition and preservation of a portion of Manzanar Internment Camp as an historical unit of the state park system." The resolution read in part:

WHEREAS. A shameful chapter in American history was written during World War II, when thousands of American citizens were locked up in concentration camps without a trial — their only crime being that they were born of Japanese ancestry; and

WHEREAS, Because of the trauma caused by the disaster at Pearl Harbor, reason was driven from the minds of many American people, and liberals and conservatives alike demanded the imprisonment of the Japanese-Americans without trial; and

WHEREAS, One of the most notorious of the concentration camps was Manzanar near the town of Lone Pine; and

WHEREAS, Rather than allowing Manzanar, and what it stood for, to fade into the forgotten past, a portion of it ought to be preserved and restored to monument of what can happen in America to Americans. . . . [54]

On September 16, 1974, the Department of Parks and Recreation released its mandated report entitled, Manzanar: Feasibility Study. The study noted that the "historic significance of the internment camp of the Japanese Americans can certainly be regarded as a notable aspect of U.S. history in relation to mass wartime psychology as exemplified by the public and official reaction to the presence of Japanese populations in America at the outbreak of World War II." The "fact that 10,000 Japanese Americans were forced to live at Manzanar, their Constitutional rights denied, is a sad chapter in U.S. and California history." Accordingly, the study found that the "entire formerly enclosed 495-acre camp area, plus cemetery, is necessary for an adequate interpretation of the Manzanar story." Since the City of Los Angeles "values this land only for its water rights," it "should be feasible to transfer the land to the State Park System at no cost to the state.

According to the study, the "primary purpose of this project would be historic interpretation." A supplemental purpose "would be development of a garden with structures for shelter." This facility "would provide former inmates solace, the general community an opportunity to reflect and focus on the area's history, and the traveler a resting place." Commercialism was not "intended," and interpretation would "project the story of Manzanar objectively" This would "be accomplished in reconstructed evacuee barracks," and a citizen's advisory committee would be established to assist the state in the interpretive effort. A "road would be reconstructed through the camp following former road patterns to the cemetery just outside the rear boundary," and the "entire camp area would be fenced with barbed wire to control access, which will help reduce the vandalism potential and impart more of the original camp feeling." Physical remains throughout the camp site, "such as foundations, roads, gardens, and trees, would also be interpreted, but not restored." There was "a possibility that one guard tower could be reconstructed." [55]

The efforts by the Department of Parks and Recreation to establish a state historical park at Manzanar faced considerable opposition throughout the 1970s. In 1979, for instance, organizers for a reunion of former Manzanar farmers and community residents sent a letter to the department protesting the proposed development at the Manzanar site which would focus exclusively on the relocation center period. [56]

On March 7, 1979, the Lone Pine Chamber of Commerce sent a letter to Governor Edmund G. Brown, Jr., protesting the proposed plan as "costly, unnecessary and totally unacceptable to the area residents." The Chamber of Commerce could "anticipate nothing "but bad feelings and enmity resulting from the implementation of such a plan." The Chamber of Commerce had "very strong feelings regarding the aesthetics and safety factors" of the plan, and the "pioneer history of the Manzanar area speaks for itself and does not require keying in on 3 1/2 short years for its claim to fame or infamy as the case may be." [57]

Native American groups also protested "the projected plan to construct the site for a memorial park to commemorate the limited time Japanese Americans were restricted at Manzanar. On March 12, 1979, a group of Owens Valley Tribal Elders wrote to Inyo County Supervisor Wilma Muth:

We want to point the fact that Indians have a definite history in this Valley . . . .

. . . We want to mention a painful memory of our people when a great number of our ancestors were slaughtered along the way through and near Manzanar at the hands of the U.S. Government while being driven south on foot to an unknown destination, the valley is sprinkled with the blood and bones of our ancestors. [58]

During subsequent years, Manzanar and the government's evacuation and relocation policies during World War II became topics of considerable debate both at the national and the state and local levels of government. On February 19, 1976, for instance, President Gerald R. Ford rescinded Executive Order 9066, issued by President Roosevelt 34 years before. [59] In his proclamation, Ford noted: "We know now what we should have known then: not only was [the] evacuation wrong, but Japanese-Americans were and are loyal Americans." [60]

In 1977, the City of Los Angeles Cultural Heritage Board declared Manzanar a City Historic Landmark. On July 30, 1976, the "Manzanar War Relocation Center" was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In February 1985, Manzanar was designated as a National Historic Landmark. [61]

As Manzanar was gaining recognition as a historic site deserving preservation and interpretation, the federal government moved toward admission that the evacuation and relocation programs during World War II had been errors. In 1980, for instance, Congress established the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians to review the circumstances surrounding Executive Order 9066 and its impact on American citizens, as well as aliens, and to recommend remedies. The commission conducted lengthy hearings and published its findings in a report, entitled Personal Justice Denied, in 1982. On August 10, 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed into legislation a bill providing a review of convictions and pardons of crimes for noncooperation with various facets of the evacuation program, as well as payment of $20,000 to each surviving individual who was evacuated and relocated under Executive Order 9066. The legislation established the Civil Liberties Public Education Fund and a board to administer its activities. While the Japanese American community remained divided over whether redress went far enough, the move to establish Manzanar as a historic site was seen by some observers to "offer an opportunity for education and enlightenment that could go a long way toward healing this still-open wound." [62]