|

MANZANAR

Historic Resource Study/Special History Study |

|

CHAPTER THREE:

EVACUATION OF PERSONS OF JAPANESE ANCESTRY FROM THE WEST COAST OF THE UNITED STATES: IMPLEMENTATION OF EXECUTIVE ORDER 9066

With the signing of Executive Order 9066, the foundation for mass evacuation of Japanese Americans from the west coast was set. American citizens of Japanese ancestry would be required to move from the west coast on the basis of wartime military necessity and the way was open to move any other group the military thought necessary. For the War Department and the Western Defense Command, the problem now became primarily one of method and operation, not basic policy. General DeWitt first tried "voluntary" resettlement under which the Issei and Nisei were to move outside restricted military zones on the West coast, as well as outside the boundaries of his command, but were free to go wherever they chose. From a military standpoint, this policy was bizarre and impractical. If the Issei and Nisei were being excluded because they threatened sabotage and espionage, why would they be left at large in the interior where there were innumerable dams, power lines, bridges, and war industries vital to the nation's security to be spied upon or disrupted. Sabotage in the interior could also be synchronized with a Japanese military invasion for a powerful fifth column effect. Thus, "voluntary" evacuation raised substantial doubts about how gravely the War Department regarded the threat. The implications were not lost on the citizens and politicians of the interior western states; they believed that people who were a threat to wartime security on the west coast were equally dangerous in the interior.

For the Issei and Nisei, "voluntary" relocation was highly impractical. Quick sale of a business or a farm with crops in the ground could not be expected at a fair price. Most businesses that relied on the ethnic trade in the "Little Tokyos" of the west coast could not be sold for anything close to market value. The absence of fathers and husbands who had been incarcerated in government internment camps following Pearl Harbor and the lack of liquidity after funds were frozen made matters more difficult. It was not easy to leave familiar surroundings, and the prospect of a deeply hostile reception in some unknown location in the interior was a powerful deterrent to moving.

Inevitably, the government ordered mandatory mass evacuation controlled by the Army, the Japanese Americans first being ordered to assembly centers — temporary staging areas, typically at fairgrounds and racetracks — and from there to relocation centers — bleak, barbed-wire-enclosed camps in the interior. Mass evacuation proceeded in one locality after another along the west coast, on short notice, with military thoroughness and lack of sentimentality. As Executive Order 9066 required, government agencies attempted, only partially successful, to protect the property and economic interests of the people removed to the camps. The loss of liberty of the Japanese Americans, however, resulted in enormous economic losses.

During the months following Executive Order 9066, none of the political entities in American society came to the aid of the Nisei or their alien parents. Congress promptly passed, without debate on questions of civil rights and civil liberties, a criminal statute prohibiting violation of military orders issued under the executive order. The district courts rejected Nisei pleas and arguments, both on habeas corpus petitions and on the review of criminal convictions for violating General DeWitt's curfew and exclusion orders.

Public opinion on the west coast and in the country at large, enflamed by the continuing racial animosity and war hysteria fostered by the press, did nothing to temper its violently anti-Japanese rage. Only a handful of citizens and organizations — a few churchmen, a small part of organized labor, and a few isolated citizens — spoke out for the rights and interests of the Japanese Americans.

Thus, the Nisei and Issei had little alternative but to comply with the mass evacuation program. Few in numbers, bereft of friends, and fearful that the war hysteria would bring mob violence and vigilantism that law enforcement would do little to control, they were left only to choose a resistance which would have proven the very disloyalty that they denied. Each carried a personal burden of rage, resignation, or despair to the assembly centers and camps that the government hastily constructed to "protect" more than 130,000,000 Americans against 60,000 Nisei and their resident alien parents. [1]

CONGRESSIONAL ACTS

Executive Order 9066 gave the military the power to issue orders, but it could not impose sanctions for failure to obey them. The Roosevelt Administration quickly turned to Congress to obtain that authority. By February 22, 1942, three days after the order was signed, the War Department sent draft legislation to the Justice Department for review and comment. General DeWitt wanted mandatory imprisonment and a felony sanction because "you have greater liberty to enforce a felony than you have to enforce a misdemeanor, viz. You can shoot a man to prevent the commission of a felony." [2] On March 9, Secretary of War Stimson sent the proposed legislation to Congress where the bill was introduced immediately by Senator Robert Reynolds of North Carolina, Chairman of the Senate Committee on Military Affairs, and by Representative John M. Costello, a friendly California Democrat on the House Committee of Military Affairs. [3]

Executive Order 9066 represented what the west coast Congressional delegation had demanded of the president and the War Department. Congressman John H. Tolan of California, who chaired the House Select Committee Investigating National Defense Migration that examined the evacuation from prohibited military areas during hearings on the west coast between February 21 and March 12, 1942, characterized the order as "the recommendation in almost the same words of the Pacific coast delegation." [4]

The Tolan Committee hearings were instituted at the behest of Carey McWilliams, Chief of the California Division of Immigration and Housing, with the intent of forestalling mass evacuation by giving a forum to moderate voices. The hearings, however, boomeranged. Members of the Tolan Committee continued to support the implementation of Executive Order 9066 after the hearings. They began the hearings persuaded that espionage and fifth column activity by Issei and Nisei in Hawaii had been central to the success of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harber. Censorship in Hawaii meant that the only authoritative news from the islands was official government sanctioned information. With regard to sabotage and fifth column activity, that version of events was still largely made up of two pieces: Secretary Knox's firmly stated December views that local sabotage had substantially aided the attack, and the Roberts' Commission's silence about fifth column activity Thus, there was no effective answer to be made when Tolan challenged pro-Nisei witnesses. Not privy to the facts in Hawaii, advocates of Japanese American loyalty, such as the Japanese American Citizens League, were frequently reduced to arguing lamely that the mainland Nisei were different from, and more reliable than, the residents of Hawaii. This view of Pearl Harbor explains in part the continuing argument, repeated by the Tolan Committee, that the lack of sabotage only showed that enemy loyalists were waiting for a raid or invasion to trigger organized activity. [5]

During the Tolan Committee hearings, the Nisei spoke in their own defense, a few academics, churchmen, and labor leaders, supporting them. The strongest statements in support of the Japanese Americans came from A. L. Wirin, Counsel for the Southern California Branch of the American Civil Liberties Union, and Louis Goldblatt, Secretary of the State Congress of Industrial Organizations. In his testimony, Wirin observed:

....there must be a point beyond which there may be no abridgement of civil liberties and we feel that whatever the emergency, that persons must be judged, so long as we have a Bill of Rights, because of what they do as persons We feel that treating persons, because they are members of a race, constitutes illegal discrimination, which is forbidden by the fourteenth amendment whether we are at war or peace. [6]

Much of the testimony before the Tolan Committee, however, assumed that mass evacuation was a fait accompli, and addressed secondary issues such as treatment during evacuation. Traditional anti-Japanese voices, such as the California Joint Immigration Committee, testified in support of the executive order, reiterating the historical catalogue of anti-Japanese charges. The press encouraged anti-Japanese sentiments by reporting primarily testimony that supported evacuation. [7]

Several events occurred on the west coast soon after the Tolan Committee hearings began, heightening public war hysteria and adding urgency to the demands for immediate mass evacuation. On February 23, four days after the signing of Executive Order 9066 and two days after the hearings commenced, an oil refinery at Goleta on the California coast near Santa Barbara, north of Los Angeles, was shelled by a surfaced Japanese submarine, identified after the war as the I-17 commanded by Kozo Nishino, a captain in the Japanese navy This was the occasion for the publication of eye-witness accounts identifying the craft as a Japanese submarine and spurious reports of signaling activities on shore. Two days later, on February 25, in the "Battle of Los Angeles," one to five unidentified planes were reported over the city which was blacked out. Antiaircraft guns were fired. None of the planes (if there were any) over Los Angeles were ever identified as Japanese. However, the two incidents received widespread coverage in the press and provided increased support to demands for the immediate removal of all persons of Japanese descent from the west coast. [8]

Earl Warren, then Attorney General of California and preparing to run for governor of the state later that year, strongly supported the anti-Japanese forces during his testimony at the Tolan hearings. One of the first witnesses, Warren presented his views at length to the committee. He candidly admitted that California had made no sabotage or espionage investigation of its own and that he had no evidence of sabotage or espionage. In place of evidence Warren offered extensive documentation concerning Japanese American cultural patterns and ethnic organizations as well as the opinions of California law enforcement officers, illustrating his testimony with maps showing Nisei land ownership. Among other things, he observed:

I do not mean to suggest that it should be thought that all of these Japanese who are adjacent to strategic points are knowing parties to some vast conspiracy to destroy our State by sudden and mass sabotage. Undoubtedly, the presence of many of these persons in their present locations is mere coincidence, but it would seem equally beyond doubt that the presence of others is no coincidence. It would seem difficult, for example, to explain the situation in Santa Barbara County by coincidence alone.

After stating that Japanese farmers and property owners flanked virtually every principal military installation, utility, airfield, bridge, telephone and power line, harbor entrance, oil field, and open stretch of beach in Santa Barbara County suited for landing purposes, Warren noted that "there were no Japanese on the equally attractive lands between these points." He concluded:

Such a distribution of the Japanese population appears to manifest something more than coincidence. But, in any case, it is certainly evident that the Japanese population of California is, as a whole, ideally situated, with reference to points of strategic importance, to carry into execution a tremendous program of sabotage on a mass scale should any considerable number of them be inclined to do so. [9]

As late as February 8, Warren had advised the state personnel board that it could not bar Nisei employees on the basis that they were children of enemy alien parentage, stating that such action was a violation of constitutionally-protected liberties. [10] This earlier position undoubtedly provided his testimony before the Tolan Committee with special effectiveness. Although Warren may have presented his views to General DeWitt earlier in February, it is interesting to note that the aforementioned War Department's Final Report, prepared principally by DeWitt and published in 1943, repeated much of Warren's presentation to the Tolan Committee virtually verbatim without attribution as the central arguments for the issuance of Executive Order 9066. [11]

Although Warren's presentation before the Tolan Committee provided no proof or evidence, the overpowering mass of his data — maps and letters and lists from all parts of the state — gripped the public imagination and turned the discussion to fruitless argument about such questions as whether land was bought before or after a power line or plant was built. These were not weeks of calm reflection on the west coast, and there was little or no focus on the meaning or significance of this "evidence." [12]

In late February and early March, the Tolan Committee assumed that Secretary Knox had evidence to substantiate his "Fifth Column" charges and that President Roosevelt had based his signing of Executive Order 9066 on informed factual analysis. The views of anti-Japanese witnesses added substance and confirmed what was already publicized and suspected. Although the committee was eager to see that the property of aliens was safeguarded by the government and wanted the Army to be concerned about hardship cases in an evacuation, it returned to Washington unwilling to challenge the need for Executive Order 9066 and the evacuation. Despite its support of the executive order, however, the Tolan Committee would issue reports during the next several months in which it began to raise questions about the policy underlying exclusion and removal. [13]

In the aftermath of the Tolan Committee hearings, Congress took up the matter of legislation that would put teeth into enforcement of the new evacuation program, making criminal any violation of Executive Order 9066. There was no civil liberty opposition in Congress, and the Nisei, few of whom were of voting age, had no voice in that legislative body Thus, debate over the bill to formalize the order as a federal statute focused only on the inclusive wording of the bill, no one publicly questioning the military necessity of the action or its intrusion into the fundamental liberties of American citizens. Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio spoke briefly against the bill, although he did not vote against it:

I think this is probably the "sloppiest" criminal law I have ever read or seen anywhere. I certainly think the Senate should not pass it. I do not want to object, because the purpose of it is understood. . . .

[The bill] does not say who shall prescribe the restrictions. It does not say how anyone shall know that the restrictions are applicable to that particular zone. It does not appear that there is any authority given to anyone to prescribe any restriction. . . .

I have no doubt an act of that kind would be enforced in war time. I have no doubt that in peacetime no man could ever be convicted under it, because the court would find that it was so indefinite and so uncertain that it could not be enforced under the Constitution. [14]

The debate was no more pointed or cogent in the House, where there seemed to be some suggestion that the bill applied to aliens rather than citizens. [15] The bill became Public Law 503, passing by voice vote in both houses on March 19, and it was signed into law by President Roosevelt on March 21, 1942. [16] The law stated:

That whoever shall enter, remain in, leave, or commit any act in any military area or military zone prescribed, under the authority of an Executive Order of the President, by the Secretary of War, or by any military commander designated by the Secretary of War, contrary to the restrictions applicable to any such areas or zone or contrary to the order of the Secretary of War or any such military commander, shall, if it appears that he knew or should have known of the existence and extent of the restrictions or order and that his act was in violation thereof, be guilty of misdemeanor and upon conviction shall be liable to a fine of not to exceed $5,000 or to imprisonment for not more than one year, or both, for each offense. [17]

This ratification of executive branch actions under Executive Order 9066 was significant, because another independent branch of the federal government now stood formally behind the exclusion and evacuation of Japanese Americans. During 1943 and 1944, the Supreme Court gave great weight to the Congressional action in upholding the imposition of a curfew as well as the evacuation itself. [18]

INITIAL PROCLAMATIONS TO IMPLEMENT THE EXECUTIVE ORDER

Executive Order 9066 empowered the Secretary of War or his delegate to designate military areas to which entry of any or all persons would be barred whenever such action was deemed militarily necessary or desirable. On February 20, 1942, the day after President Roosevelt signed the order, Secretary Stimson wrote to General DeWitt delegating authority to implement the order within the Western Defense Command and setting forth a series of specific requests and instructions. American citizens of Japanese descent, Japanese and German aliens, and any persons suspected of being potentially dangerous were to be excluded from designated military areas. Everyone of Italian descent was to be omitted from any plan of exclusion, at least for the time being, because they were "potentially less dangerous, as a whole." DeWitt was to consider redesignating the Justice Department's prohibited areas as military areas, excluding Japanese and German aliens from those areas by February 24 and excluding "actually" suspicious persons as soon as practicable." Full advantage was to be taken of voluntary exodus. People were to be removed gradually to avoid unnecessary hardship and dislocation of business and industry "so far as is consistent with national safety." Accommodations for the evacuees were to be established before the exodus, with proper provision for housing, food, transportation, and medical care, and evacuation plans were to include protection for evacuees' property. [19]

On February 23, Colonel Bendetsen arrived in San Francisco to serve as a liaison officer between DeWitt and Assistant Secretary of War McCloy and to help in the execution of the War Department directives. With his assistance, DeWitt drafted and obtained War Department approval of his first public proclamation for the evacuation program and an accompanying press release, both of which were issued on March 2. Public Proclamation No. 1, announced as a matter of military necessity the establishment of Military Areas Nos. 1 and 2. Military Area No. 1 included the approximate western half of Washington, Oregon, and California and the southern half of Arizona. All portions of those states not included in Military Area No. 1 were placed in Military Area No. 2. The proclamation also established a number of zones; Zones A-I through A-99, which included a strip about fifteen miles wide running the entire length of the coast and along the Mexican border, were primarily within Military Area No. 1, while Zone B constituted the remainder of Military Area No. 1. The proclamation noted that in the future people might be excluded from Military Area No. 1 and from Zones A-2 to A-99 and that the designation of Military Area No. 2 did not contemplate restrictions or prohibitions except with respect to the designated zones. In this proclamation, for the first time, restrictions were applied not only to "any Japanese, German or Italian alien" but also to "any person of Japanese ancestry." All such persons residing in Military Area No. 1 who changed their residence, were required to file a form with the post office. Finally, the proclamation expressly continued the prohibited and restricted areas designated earlier by the Attorney General. [20]

In the press release accompanying his first proclamation, DeWitt stated that orders would eventually be issued "requiring all Japanese, including those who are American born, to vacate all of Military Area No. 1." He added that those "Japanese and other aliens who move into the interior out of this area now will gain considerable advantage, and in all probability will not again be disturbed." Only after the Japanese had been excluded would German and Italian aliens be evacuated, and some of these would be entirely exempt from evacuation. [21]

DeWitt issued Public Proclamations Nos. 2 and 3 during the next several weeks. Public Proclamation No. 2, issued March 16, established four military areas covering the states of Idaho, Montana, Nevada, and Utah and listed 933 additional prohibited zones. [22] Public Proclamation No. 3, issued on March 24 and effective on March 27 affected the daily lives of Japanese Americans directly, instituting a curfew regulation requiring all enemy aliens and "persons of Japanese ancestry" to be in their homes between 8 p.m. and 6 a.m. The proclamation provided that "at all other times all such persons shall only be at their place of residence or employment or travelling between those places or within a distance of not more than five miles from their place of residence." They could continue to move out of the military area if they did so during noncurfew hours. [23]

VOLUNTARY EVACUATION

In late February and early March, both the War Department and General DeWitt hoped that the mere announcement of prohibited and restricted zones would induce a voluntary migration out of these zones, as had been the case in the California prohibited zones previously announced by the Department of Justice in the aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attack. Bendetsen, for example, noted that many aliens ordered to move after Pearl Harbor had found new residences for themselves; thus, he felt the Army should not advertise that it would provide food and housing for those it displaced because numerous aliens might take advantage of a free "living." He also supported voluntary migration because he thought the Army should not be responsible for resettlement, since such action would divert the military from its primary task of winning the war. DeWitt estimated that 15,000 persons moved out of the Justice Department's prohibited zones by midnight, February 24 Most of them had moved into adjacent restricted zones in urban areas. Thus, in his press release of March 2, DeWitt urged the continuation of this voluntary migration of Japanese from Military Area No. 1 along the coast to the interior. [24]

It soon became apparent to many observers, however, that the voluntary program could not work. As early as February 21, the Tolan Committee received complaints from interior areas to which the evacuees were moving, indicating that fears of sabotage and destruction were spreading inland. [25] The Japanese who were willing to migrate also struggled with problems of insecurity as evidenced by a statement to the Tolan Committee by the Emergency Defense Council of the Seattle Chapter, Japanese American Citizens League:

A large number of people have remarked that they will go where the Government orders them to go, willingly, if it will help the national defense effort. But the biggest problem in their minds is where to go. The first unofficial evacuation announcement pointed out that the Government did not concern itself with where evacuees went, just so they left prohibited areas. Obviously this was no solution to the question, for immediately, from Yakima, Idaho, Montana, Colorado and elsewhere authoritative voices shouted: 'No Japs wanted Here!'

The Japanese feared with reason that, forced to vacate their homes, unable to find a place to stay, they would be kicked from town to town in the interior like the 'Okies' of John Steinbeck's novel. Others went further, and envisioned the day when inhabitants of inland States, aroused by the steady influx of Japanese, would refuse to sell gasoline and food to them. They saw, too, the possibility of mob action against them as exhausted, impoverished and unable to travel further, they stopped in some town or village where they were not wanted. [26]

As a result of such developments, political officials, including Earl Warren and Richard Neustadt, the regional director of the Federal Security Agency, realized that only a mandatory evacuation and relocation program operated by the government could work. [27]

The reaction from the interior states was direct and forceful. On February 21, for instance, Governor Carville of Nevada informed General DeWitt that permitting unsupervised enemy aliens to go to all parts of the country, particularly his state, would be conducive to the spread of sabotage and subversive activities:

I have made the statement here that enemy aliens would be accepted in the State of Nevada under proper supervision. This would apply to concentration camps as well as to those who might be allowed to farm or do such other things as they could do in helping out. This is the attitude that I am going to maintain in this State and I do not desire that Nevada be made a dumping ground for enemy aliens to be going anywhere they might see fit for travel. [28]

Although Governor Ralph L. Carr of Colorado was characterized by many contemporaries as the one mountain state chief executive receptive to relocation of the Issei and Nisei, his radio address of February 28, 1942, offered a vivid impression of the emotions associated with the relocation of the Japanese in the interior:

If those who command the armed forces of our Nation say that it is necessary to remove any persons from the Pacific coast and call upon Colorado to do her part in this war by furnishing temporary quarters for those individuals, we stand ready to carry out that order. If any enemy aliens must be transferred as a war measure, then we of Colorado are big enough and patriotic enough to do our duty. We announce to the world that 1,118,000 red-blooded citizens of this State are able to take care of 3,500 or any number of enemies, if that be the task which is allotted to us. . . .

The people of Colorado are giving their sons, are offering their possessions, are surrendering their rights and privileges to the end that this war may be fought to victory and permanent peace. If it is our duty to receive disloyal persons, we shall welcome the performance of that task.

This statement must not be construed as an invitation, however. Only because the needs of our Nation dictate it, do we even consider such an arrangement. In making the transfers, we can feel assured that governmental agencies will take every precaution to protect our people, our defense projects, and our property from the same menace which demands their removal from those sections. [29]

Federal officials were also beginning to realize the hardship which the "voluntary" program was posing for evacuees. Secretary Knox, for instance, forwarded to the attorney general a report that the situation of the Japanese in southern California was becoming critical because they were being forced to move with no provision for housing or means of livelihood. McCloy, who although continuing to favor the voluntary program, wrote to Harry Hopkins, one President Roosevelt's leading advisers at the White House, that one "of the drawbacks they have is the loss of their property. A number of forced sales are taking place, and, until the last minute, they hate to leave their land or their shop." [30]

Inevitably, the voluntary evacuation failed. On March 21, Colonel Bendetsen recommended the termination of voluntary migration, and four days later DeWitt determined that it should end. The Army recognized this failure in Public Proclamation No. 4 issued on March 27, the same day that Public Proclamation No. 3 went into effect. The proclamation prohibited all persons of Japanese ancestry in Military Area No. 1, where most of them still lived, from changing their residence without permission or approval from the Army, effective midnight, March 29. [31] The Western Defense Command explained that the proclamation was designed "to ensure an orderly, supervised, and thoroughly controlled evacuation with adequate provision for the protection . . . of the evacuees as well as their property." Thus, the evacuees, according to the military, would be shielded from intense public hostility by this approach. [32]

Government statistics, although not entirely consistent, show the failure of the voluntary evacuation program. The change-of-address cards required by Public Proclamation No. 1 show the number of people who voluntarily relocated before March 29. In the three weeks following March 2, only 2,005 of the approximately 107,500 persons of Japanese descent who lived in Military Area No. 1 moved out. These statistics alone demonstrated that voluntary migration would not achieve evacuation. Public Proclamation No. 4 was issued on March 27 and became effective at midnight March 29. In the interval, approximately 2,500 cards show moves out of Military Areas Nos. 1 and 2. The statistics in the War Department's Final Report show discrepancies concerning the number of voluntary evacuees. They show that from March 12 to June 30, 1942, 10,312 persons reported their "voluntary" intention to move out of Military Area No, 1. But a net total of less than half that number — 4,889 — left the areas as part of the voluntary program. Of these voluntary migrants, 1,963 went to Colorado, 1,519 to Utah, 305 to Idaho, 208 to eastern Washington, 115 to eastern Oregon, and the remainder to other states. The Final Report concludes that this net total "probably accounts for 90 percent of the total number of Japanese ... who voluntarily left the West Coast area for inland points." [33]

ESTABLISHMENT OF THE WAR RELOCATION AUTHORITY AND THE WARTIME CIVIL CONTROL ADMINISTRATION

While the voluntary program was failing, government officials and others began to propose programs designed to benefit the evacuees. On February 20, 1942, Carey McWilliams, a California state official who later became editor of The Nation, sent a telegram to Biddle recommending that the president establish an Alien Control Authority operated by representatives of federal agencies. The agency would register, license, settle, maintain, and reemploy the evacuees, and conserve alien property. During the first week of March, John Collier, Commissioner of Indian Affairs in the Department of the Interior, proposed a constructive program for the evacuees, including useful work, education, health care, and other services, as well as a plan for rehabilitation after the war. While these recommendations were being circulated, the Tolan Committee filed an interim report which showed great prescience about future problems and concern for the fate of the evacuees. [34]

As these recommendations were being circulated, the realization that voluntary migration was failing and that considerable manpower would be needed to implement a mandatory evacuation program led to further discussions by federal officials as to how the government might systematize the process and supervise the evacuees. The War Department was eager to be out of the resettlement business, and discussed with the attorney general and the Budget Bureau the mechanism for setting up a permanent organization to take over the job. In his record of a Cabinet meeting discussion at the White House on February 27, Secretary Stimson noted:

The President brought this up first of all and showed that thus far he has given very little attention to the principal task of the transportation and resettlement of the evacuees. I outlined what DeWitt's plan was and his proclamation [Public Proclamation No. 1] so far as I could without having the paper there. Biddle supported us loyally, saying that he had the proclamation already in his hands. I enumerated the five classes in the order which are being affected and tried to make clear that the process was necessarily gradual, DeWitt being limited by the size of the task and the limitations of his own force. The President seized upon the idea that the work should be taken off the shoulders of the Army so far as possible after the evacuees had been selected and removed from places where they were dangerous. There was general confusion around the table arising from the fact that nobody had realized how big it was, nobody wanted to take care of the evacuees, and the general weight and complication of the project. Biddle suggested that a single head should be chosen to handle the resettlement instead of the pulling and hauling of all the different agencies, and the President seemed to accept this; the single person to be of course a civilian and not the Army . . . [35]

As a result of this discussion, Milton S. Eisenhower, Assistant to the Secretary of the Agriculture as director of information and coordinator of the department's land use programs and a brother of Dwight D. Eisenhower, a fast-rising and popular general in the military, was selected as the civilian to oversee the Japanese evacuation and resettlement effort. Eisenhower, a 42-year-old native of Abilene, Kansas, had been trained as a journalist and had served in the Department of Agriculture since 1926. A candidate fully acceptable to the War Department, he worked informally on the evacuation problem from the end of February, and McCloy took him to San Francisco to meet DeWitt in March 1942. By March 17, plans for an independent authority responsible for the resettlement of Japanese Americans were completed. The next day President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9102 establishing the War Relocation Authority in the Office for Emergency Management in the Executive Office of the President, appointed Eisenhower director, and allocated $5,500,000 for the WRA. [36]

According to Executive Order 9102, the purpose of the WRA was "to provide for the removal from designated areas of persons whose removal is necessary in the interest of national security." The director was given wide discretion; the executive order did not expressly provide for relocation camps, but it gave the director authority to "accomplish all necessary evacuation not undertaken by the Secretary of War or appropriate military commander, provide for the relocation of such persons in appropriate places, provide for their needs in such manner as may be appropriate, and supervise their activities." The director was to "provide, insofar as feasible and desirable, for the employment of such persons at useful work in industry, commerce, agriculture, or public projects, prescribe the terms and conditions of such public employment, and safeguard the public interest in the private employment of such persons." [37]

Until a meeting with the governors and other officials of ten western and intermountain states at Salt Lake City on April 7, the War Relocation Authority under Eisenhower continued to hope that it could arrange for the resettlement of a substantial number of the evacuated Japanese in the interior and provide for their employment in public works, land development, agricultural production, and manufacturing in the relocation areas. But the intransigent attitudes exhibited at that meeting persuaded all concerned that the Japanese, whether aliens or citizens, would have to be kept indefinitely in large government-operated camps, called relocation centers, to be hastily constructed by the Corps of Engineers during the spring and summer of 1942. With that final destination placed in the hands of a civilian agency, the Army was ready to push firmly ahead with its part of the evacuation. [38]

On March 10, 1942, eight days prior to the establishment of the WRA, General DeWitt established a civil affairs organization of his own to handle evacuation problems and facilitate voluntary migration. The War Department directives of February 20 to DeWitt in effect placed the Western Defense Command's evacuation operations under the direct supervision of the Secretary of War, and, as aforementioned, Colonel Bendetsen was chosen as coordinator of evacuation issues between Washington and San Francisco. Because Army headquarters was facing an impending general reorganization, the arrangements for supervision from Washington were somewhat confused, thus necessitating Bendetsen's role as coordinator. After the reorganization of March 9, the Washington military staff agencies would almost disappear from the picture as far as evacuation supervision was concerned, except for planning and direction of construction of assembly centers by the Corps of Engineers with staff supervision by the Services of Supply. During a visit by McCloy to the west coast, DeWitt established a Civil Affairs Division in his general staff on March 10. The following day he created the Wartime Civil Control Administration to act as his operations agency to carry out assigned missions involving civilian control and evacuation program procedures. At McCloy's urging, Colonel Bendetsen was transferred from the War Department staff and designated as Assistant Chief of Staff for Civil Affairs, General Staff, and also as Director, WCCA. Thomas Clark was loaned to the WCCA by the Justice Department to be head of its civilian staff and coordinate the many federal civilian agencies that took part in the evacuation program. The WCCA initiated its operations with a brief, but nonetheless comprehensive, directive from DeWitt:

To provide for the evacuation of all persons of Japanese ancestry. . . . with a minimum of economic and social dislocation; a minimum use of military personnel and maximum speed; and initially to employ all appropriate means to encourage voluntary migration. [39]

Although the principal activities of the WCCA would focus on processing the evacuees, the new organization initially established 48 service offices, one in each area of significant Japanese population in the area to be affected by evacuation, to facilitate voluntary migration. Announcements "through every available public information channel" encouraged evacuees to visit these offices in order to receive aid in undertaking voluntary movement. The offices were staffed by representatives of various federal agencies that were equipped to provide help to the evacuees. Provisions were made to assist in property settlements, provide social counseling and travel permits, and lend financial assistance to those evacuees who needed it. The WCCA offices also offered to locate specific employment opportunities in interior areas for voluntary migrants. [40]

ASSEMBLY CENTER SELECTION

Once the decision was made that evacuation would no longer be voluntary, a plan for immediate compulsory evacuation was needed. To facilitate the evacuation effort, the WCCA determined to separate evacuation from the problem of removing evacuees to more permanent relocation centers. The War Department's Final Report stated:

It was concluded that evacuation and relocation could not be accomplished simultaneously. This was the heart of the plan. It entailed the provision for a transitory phase. It called for establishment of Assembly Centers at or near each center of evacuee population. These Centers were to be designed to provide shelter and messing facilities and the minimum essentials for the maintenance of health and morale....

The program would have been seriously delayed if all evacuation had been forced to await the development of Relocation Centers. The initial movement of evacuees to an Assembly Center as close as possible to the area of origin also aided the program (a) by reducing the initial travel; (b) by keeping evacuees close to their places of former residence for a brief period while property matters and family arrangements which had not been completed prior to evacuation could be settled; and (c) by acclimating the evacuees to the group life of a Center in their own climatic region. [41]

During the period of the voluntary evacuation program, the Army had begun the search for appropriate camp facilities, both temporary and more permanent. Regarding the criteria for selection of assembly centers, as the temporary camps came to be called, General DeWitt later wrote:

Assembly Center site selection was a task of relative simplicity As time was of the essence, it will be apparent that the choice was limited by four rather fundamental requirements which virtually pointed out the selections ultimately made. First, it was necessary to find places with some adaptable pre-existing facilities suitable for the establishment of shelter, and the many needed community services. Second, power, light, and water had to be within immediate availability as there was no time for a long pre-development period. Third, the distance from the Center of the main elements of evacuee population served had to be short, the connected road and rail net good, and the potential capacity sufficient to accept the adjacent evacuee group. Finally it was essential that there be some area within the enclosure for recreation and allied activities as the necessary confinement would otherwise have been completely demoralizing. The sudden expansion of our military and naval establishments further limited the choice. [42]

By early March 1942, the Army had selected issued instructions to establish these centers two sites as "reception centers." DeWitt through which Japanese Americans would be funneled out of Military Area No. 1. Work began immediately on the construction of the two centers — Manzanar at the eastern base of the Sierra Nevada in Owens Valley in eastern California and Poston south of Parker Dam on the Colorado River Indian Reservation in Arizona. The two sites, located in barren areas and constructed to house some 10,000 evacuees each, were designed "to provide temporary housing for those who were either unable to undertake their own evacuation, or who declined to leave until forced to." Designed initially by the WCCA as assembly centers to provide temporary quarters for evacuees, the two sites would later become two of the ten permanent relocation centers under the WRA. [43]

Meanwhile, the other assembly center sites, which were to serve as temporary quarters for the evacuees, were selected with dispatch. On March 16, Bendetsen dispatched two site-selection teams of federal officials, including representatives of the Bureau of Reclamation in the Department of the Interior, the National Resources Planning Board, Soil Conservation Service, and Farm Security Administration in the Department of Agriculture, the Works Projects Administration, and the Corps of Engineers, South Pacific Division, with instructions to locate facilities capable of housing 100,000 people. Within four days these teams reported back to Bendetsen, listing between them 17 potential sites. The War Department's Final Report described their selection:

After an intensive survey the selections were made. Except at Portland, Oregon, Pinedale and Sacramento, California and Mayer, Arizona, large fairgrounds or racetracks were selected. As the Arizona requirements were small, an abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps camp at Mayer was employed. In Portland the Pacific International Live Stock Exposition facilities were adapted to the purpose. At Pinedale the place chosen made use of the facilities remaining on a former mill site where mill employees had previously resided. At Sacramento an area was employed where a migrant camp had once operated and advantage was taken of nearby utilities. [44]

After quick review, DeWitt, on March 20, ordered the Army's Corps of Engineers to proceed with construction of 16 (including the Manzanar and Poston "reception centers") "Assembly Centers for the housing of evacuees," and gave the Corps of Engineers a deadline of April 21 for making the camps ready. Thirteen assembly centers were located in California (Marysville, Sacramento, Tanforan, Stockton, Turlock, Salinas, Merced, Pinedale, Fresno, Tulare, Santa Anita, Pomona, and Manzanar), and the other three at Puyallup, Washington, Portland, Oregon, and Mayer, Arizona. [45]

Thus, as systematic compulsory evacuation began, the evacuation program and the operation of the assembly centers were under the authority of the Army by agreement with the WRA. Evacuation was under military supervision, while the centers were operated by the WCCA.

TERMINAL ISLAND EVACUATION

The small-scale evacuation of Terminal Island in February 1942 was a precursor of the mass evacuation of the west coast and provided a vivid portent of the hardship that would be wrought by evacuation. Approximately six miles long and one-half mile wide, Terminal Island, most of whose residents would ultimately be evacuated to Manzanar, marked the boundaries of Los Angeles Harbor and the Cerritos Channel. Lying directly across the harbor from a U.S. Navy base at San Pedro, the island was reached in 1942 by ferry or a small drawbridge.

The isolated Japanese community on the island consisted of some 500 families, primarily occupied in the fishing and canning industries. A half-dozen fish canneries, each with its own employee housing, were located on the island. In 1942, the Japanese population of the island was approximately 3,500, of whom approximately half were American-born Nisei. The majority of the businesses, including restaurants, grocery stores, barbershops, beauty shops, and poolhalls (in addition to three physicians, and two dentists), which served the island were owned or operated by Issei or Nisei. [46]

Immediately following the Pearl Harbor attack, the FBI removed individuals from the Japanese community on Terminal Island who were considered dangerous aliens, and followed this with "daily dawn raids... removing several hundred more aliens" and sending them to internment camps in Montana and North Dakota. In late January 1942, the island was designated by authorities as a "strategic area" from which enemy aliens would be barred. Within several days, FBI agents again raided the Japanese community, arresting 336 Issei who were considered potentially dangerous. On February 10, 1942, the Department of Justice posted a warning that all Japanese aliens had to leave the island by the following Monday. The next day, a presidential order placed Terminal Island under the jurisdiction of the Navy. By the 15th, Secretary of the Navy Knox directed Rear Admiral R. S. Holmes, Commandant of the 11th Naval District in San Diego, to notify all island residents that their dwellings would be condemned, effective within 30 days. On February 25, however, the Navy informed the island residents that the deadline had been advanced to midnight, February 27, slightly more than 48 horn's away. The Terminal Islanders were, in essence, evicted, and the Navy did not care where they went as long as they left the "strategic" island. [47]

As a consequence of the FBI raids on Terminal Island, the heads of many families, as well as community and business leaders, were gone and mainly older women and minor children were left. With the new edict, these women and children, who were unaccustomed and ill equipped to handle business transactions, were forced to make quick financial decisions regarding their property and possessions. [48] Dr. Yoshihiko Fujikawa, a resident of the island, described the chaotic scene prior to evacuation:

It was during these 48 hours that I witnessed unscrupulous vultures in the form of human beings taking advantage of bewildered housewives whose husbands had been rounded up by the F. B. I. within 48 hours after Pearl Harbor. They were offered pittances for practically new furniture and appliances: refrigerators, radio consoles, etc., as well as cars, and many were falling prey to these people. [49]

The day after the Terminal Island evacuation, the former Japanese community was littered with abandoned goods and equipment, much of which would disappear or be stolen. [50] Most of the Terminal Islanders, unprepared for such an abrupt move, remained in Los Angeles County, many sleeping out in the open or sleeping under blanket tents in crowded church chapels or Japanese language schools. [51]

The experience of Henry Murikami, a Japanese fisherman on Terminal Island, was typical. He had become a fisherman after graduating from high school. After gaining experience, he leased a boat from the Van Camp Seafood Company and went into business on his own, saving money to increase and improve his fishing equipment. By the time of Pearl Harbor he owned three sets of purse seine nets valued at $22,500. After the Pearl Harbor attack, he, as well as the rest of the Japanese fishermen, were stopped from fishing and told to remain in their fishing camps. In early February, Murikami, along with every alien male on Terminal Island who held a fisherman's license, was arrested and sent to a Department of Justice internment camp in Bismarck, North Dakota. His equipment lay abandoned, accessible for the taking. [52]

INITIAL EVACUATION TO MANZANAR

Approximately three weeks after the Terminal Island evacuation and several days before the issuance of the Arms first compulsory exclusion order, a hastily-planned evacuation of some 1,000 Japanese residents from Los Angeles to Manzanar was undertaken. While assembly center site selection was underway, and before construction of the centers was completed, public pressure for initiation of a definite evacuation movement reached the point that, according to some observers, there was "grave danger of serious incidents." Accordingly, on March 23 the WCCA organized a voluntary evacuation of some 1,000 persons from Los Angeles to Manzanar where work had started on March 16 to clear land and erect housing under the direction of the Corps of Engineers. The Commanding General, Southern California Sector, Western Defense Command, provided escort for the convoy of several hundred privately-owned automobiles, from Model Ts to 1942 sedans, that assembled at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena. The vehicles were driven by their owners, the convoy being spaced by highway patrol cars and Army jeeps. The convoy "extended at some points a distance in excess of six miles." In addition to the convoy, a train transported some 500 of the evacuees from Los Angeles to Lone Pine. The Quartermaster, Western Defense Command, obtained the necessary subsistence, and the U.S. Public Health Service provided medical care. An advance party of some 80 voluntary evacuees, consisting primarily of single men and heads of families, had preceded the main party on March 21 to assist the WCCA administrative staff at Manzanar in preparing for the reception of the 1,000 evacuees. Thus, Manzanar became the first assembly or reception center to receive evacuees. [53]

COMMENCEMENT OF MANDATORY EVACUATION: EVACUATION OF BAINBRIDGE ISLAND

The first compulsory exclusion order under the Army evacuation program was issued on March 24, 1942, three days following the enactment of Public Law 503 providing criminal penalties for disobeying Executive Order 9066. The exclusion order applied to the largely agrarian and fishing Japanese community, consisting of about 54 families, on Bainbridge Island in Puget Sound, some ten miles west of Seattle, Washington, near the strategically-sensitive Bremerton Naval Base. In a sense, the Bainbridge Islanders were used as "guinea pigs" by the Army "in a kind of dress rehearsal for the full scale evacuation which was to come." The 227 Bainbridge Islanders were evacuated directly via a lengthy train trip to Manzanar, because the Puyallup Assembly Center on the Washington state fairgrounds, the nearest assembly Center site to their homes, was not ready for occupancy, and the Manzanar assembly or reception center was the only camp to be open at the time. 54]

The exclusion order directed "that all persons of Japanese ancestry, including aliens and nonaliens, be excluded from that Portion of Military Area No. 1 described as 'Bainbridge Island,' in the State of Washington, on or before 12 o'clock noon, P.W.T., of the 30th day of March 1942." The order stated that exclusion would be accomplished in the following manner:

(a) Such persons may, with permission, on or prior to March 29, 1942, proceed to any approved place of their choosing beyond the limits of Military Area No. 1 and the prohibited zones established by said proclamations [Public Proclamations Nos. 1 and 2] or hereafter similarly established, subject only to such regulations as to travel and change of residence as are now or may hereafter be prescribed by this headquarters and by the United States Attorney General. Persons affected hereby will not be permitted to take up residence or remain within the region designated as Military Area No. 1 or the prohibited zones heretofore or hereafter established. Persons affected hereby are required on leaving or entering Bainbridge Island [after 9 a. m., March 24, 1942] to register and obtain a permit at the Civil Control Office to be established on said Island at or near the ferryboat landing [at the Anderson Dock Store in Winslow].

(b) On March 30, 1942, all such persons who have not removed themselves from Bainbridge Island in accordance with Paragraph 1 hereof shall, in accordance with instructions of the Commanding General, Northwestern Sector, report to the Civil Control Office referred to above on Bainbridge Island for evacuation in such manner and to such place or places as shall then be prescribed.

(c) A responsible member of each family [preferably the head of the family or the person in whose name most of the property was held] affected by this order and each individual living alone so affected will report to the Civil Control Office described above between 8 a.m. and 5 p. m. Wednesday, March 25, 1942 [to receive further instruction].

The exclusion order went on to state that any "person affected by this order who fails to comply with any of its provisions or who is found on Bainbridge Island after 12 o'clock noon, P.W.T. of March 30, 1942" would be subject to the criminal penalties provided by Public Law 503. Alien Japanese would "be subject to immediate apprehension and internment."

The exclusion order also included specific "Instructions To All Japanese Living on Bainbridge Island." Among other things, these instructions included a list of topics for which the Civil Control Office was equipped to assist the Japanese population:

Give advice and instructions on the evacuation.

Provide services with respect to the management, leasing, sale, storage, or other disposition of most kinds of property, including farms, livestock and farm equipment, boats, tools, household goods, automobiles, etc.

Provide temporary residence for all Japanese in family groups, elsewhere.

Transport persons and a limited amount of clothing and equipment to their new residence, as specified below.

Give medical examinations and make provision for all invalided persons affected by the evacuation order.

Give special permission to individuals and families who are able to leave the area and proceed to an approved destination of their own choosing on or prior to March 29, 1942.

The exclusion order noted that there were two conditions "imposed on voluntary evacuation." The destination must be outside Military Area No. 1, and arrangements must "have been made for employment and shelter at the destination."The instructions stated further that provisions "have been made to give temporary residence in a reception center elsewhere [Puyallup Assembly Center]." Evacuees who did not go to "an approved destination of their own choice, but who go to a reception center under Government supervision, must carry with them the following property, not exceeding that which can be carried by the family or the individual." These items included:

(a) Blankets and linens for each member of the family;

(b) Toilet articles for each member of the family;

(c) Clothing for each member of the family;

(d) Sufficient knives, forks, spoons, plates, bowls, and cups for each member of the family . . . .

All items "carried will be securely packaged, tied, and plainly marked with the name of the owner and numbered in accordance with instructions received at the Civil Control Office." No contraband items, as earlier specified by the Department of Justice, could be carried.

The instructions noted that the federal government "through its agencies will provide for the storage at the sole risk of the owner of only the more substantial household items, such as ice boxes, washing machines, pianos, and other heavy furniture." Cooking utensils and other small items "must be crated, packed, and plainly marked with the name and address of the owner." All persons going to a reception center would "be furnished transportation and food for the trip." Transportation "by private means" would "not be permitted." Instructions would "be given by the Civil Control Office as to when evacuees must be fully prepared to travel." [55]

Tom G. Rathbone, field supervisor for the U.S. Employment Service, filed a report after the Bainbridge Island evacuation, with recommendations for improvement that provide a picture of the government's approach to the first compulsory exclusion order. On March 23, a meeting, attended by representatives of various federal agencies, was called by the WCCA, which oversaw operation of the civil control station on Bainbridge island, to outline evacuation procedures. After setting up the station on the island, the government group "reported to Center at 8:00 a.m for the purpose of conducting a complete registration" of the "persons of Japanese ancestry who were residents of the Island." Rathbone recommended that more complete instructions from Army officials would clarify many questions, including what articles the evacuees could take with them, the climate at the designated assembly center, and the timing of the evacuation. He also suggested better planning so that the evacuees would not be required to return repeatedly to the center. He observed that "such planning would have to contemplate the ability to answer the type of question [sic] which occur and the ability to give accurate and definite information which would enable the evacuee to close out his business and be prepared to report at the designated point with necessary baggage, etc." Further, Rathbone noted that disposition of evacuees' property following evacuation caused the most serious hardship and prompted the most questions. He reported:

We received tentative information late Friday afternoon to the effect that it was presumed that the Government would pay the transportation costs of such personal belongings and equipment to the point of relocation upon proper notice. When this word was given to the evacuees, many complained bitterly because they had not been given such information prior to that time and had, therefore, sold, at considerable loss, many such properties which they would have retained had they known that it would be shipped to them upon relocation. Saturday morning we receive additional word through the Federal Reserve Bank that the question had not been answered and that probably no such transportation costs would be paid. Between the time on Friday afternoon and Saturday morning some Japanese had arranged to repossess belongings which they had already sold and were in a greater turmoil than ever upon getting the latter information. To my knowledge, there still is no answer to this question, but it should be definitely decided before the next evacuation is attempted. [56]

The Bainbridge [slanders were the last Japanese Americans in Military Area No. 1 to have the option of moving voluntarily to an approved place of their choosing. While their evacuation was in progress, DeWitt issued the aforementioned Public Proclamation No. 4 on March 27 ending voluntary migration at midnight, March 29. [57] After the Bainbridge evacuation, exclusion orders (a copy of a typical order may be seen on pages 59-62) were issued for each of the other 98 exclusion areas in Military Area No. 1, each area having approximately 1,000 resident Japanese. In establishing the boundaries of the exclusion areas, efforts were made to adhere "to the established policy of keeping family units unbroken, and to move communities with similar social and economic backgrounds to the same Assembly Center." The evacuation process commenced with the issuance of a civilian exclusion order, a document which defined the exclusion area and provided the immediate sanction for its evacuation. The order specified the exclusion date and the registration date or dates. The order was accompanied by specific "Instructions to Evacuees" concerning their responsibilities in the evacuation program. In each area covered by a civilian exclusion order, a civil control station, staffed with representatives of the Federal Reserve Bank, Farm Security Administration, associated agencies of the Federal Security Agency, including the U.S. Employment Service, U.S. Public Health Service, and Bureau of Public Assistance of the Social Security Board, was set up under the direction of the WCCA to provide information, administer registration and medical inspection, render financial assistance, and process the evacuees. These stations were usually located in a public hail, school gymnasium, or auditorium and, whenever possible, they were near the center of the Japanese population of the area being evacuated.

The exclusion orders were issued in a sequence based upon several considerations. Military security requirements were the primary considerations, but other issues were involved as well. The ability of the assembly or reception centers to receive evacuees, the availability of civilian personnel in the various agencies which participated in the operation of control stations, the distance evacuees were to be moved, and the availability of rail or motor transportation were important factors in determining the order in which the exclusion areas were evacuated. Areas were evacuated in the order indicated by the civilian exclusion order number "with but a few exceptions."

No publicity was permitted concerning the evacuation of any specific unit area prior to the posting of the civilian exclusion order within the affected area. The evacuation operations within most exclusion areas covered a period of seven days. Exclusion orders were posted throughout the area from 12:00 noon the first day to 5:00 a.m. the second day. Registration of all persons of Japanese ancestry within the area was conducted from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. on the second and third days. Processing on preparing of evacuees for evacuation occurred from 8:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. on the fourth and fifth days. Movements of evacuees in increments of approximately 500 took place on the sixth and seventh days. [58]

The last of the exclusion orders (No. 99 affecting a small area near Sacramento) that required the departure of Japanese Americans who resided in Military No. 1 was issued on June 6, 1942. Thus, this phase of the evacuation was completed nearly six months after Pearl Harbor and two days after the stunning American naval victory over Japan in the Battle of Midway Island. [59]

EVACUEES' PROPERTY DISPOSAL

Although later evacuations tended to be better organized than the one at Bainbridge Island, difficulties continued to plague the program. The handling of evacuee property, for instance, continued to present a major problem for the government. Early in its hearings on the west coast the Tolan Committee learned that frightened, bewildered Japanese were being preyed upon by second-hand dealers and real estate profiteers. On February 28, the committee cabled Attorney General Biddle recommending that an Alien Property Custodian be appointed. [60]

Before any action was taken, however, evacuation proceedings had commenced. Spot prohibited zones had been cleared of Japanese by order of the Department of Justice immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack; the Navy had evacuated Terminal Island in Los Angeles in late February; and the Western Defense Command had urged a number of west coast residents of Japanese ancestry to leave the military area voluntarily. The military viewed its primary mission to be removal of evacuees from the designated areas rather than looking after their property.

Headquarters

Western Defense Command

and Fourth ArmyPresidio of San Francisco. California

April 20, 1942Civilian Exclusion Order No. 7

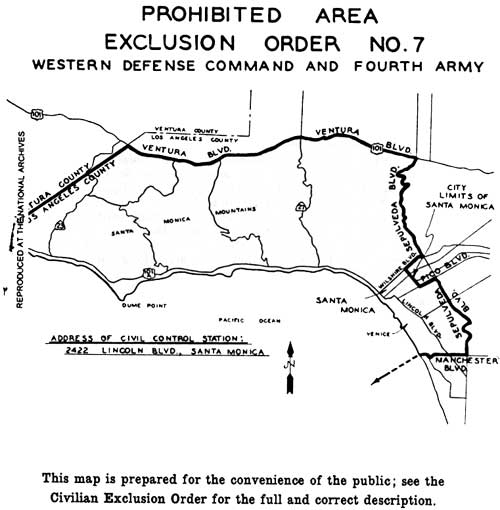

1. Pursuant to the provisions of Public Proclamations Nos. 1 and 2, this Headquarters, dated March 2, 1942, and March 16, 1942, respectively, it is hereby ordered that from and after 12 o'clock noon, P.W.T., of Tuesday, April 28, 1942, all persons of Japanese ancestry, both alien and non-alien, be excluded from that portion of Military Area No. 1 described as follows:

All that portion of the County of Los Angeles, State of California, within the boundary beginning at the point where the Los Angeles-Ventura County line meets the Pacific Ocean; thence northeasterly along said county line to U. S. Highway No. 101; thence easterly along said Highway No, 101 to Sepulveda Boulevard; thence southerly along Sepulveda Boulevard to Wilshire Boulevard; thence westerly on Wilshire Boulevard to the limits of the City of Santa Monica; thence southerly along the said city limits to Pico Boulevard; thence easterly along Pico Boulevard to Sepulveda Boulevard; thence southerly on Sepulveda Boulevard to Manchester Avenue; thence westerly on Manchester Avenue and Manchester Avenue extended to the Pacific Ocean: thence northwesterly across Santa Monica Bay to the point of beginning.

2. A responsible member of each family and each individual living alone in the above described area will report between the hours of 8:00 A. M. and 5:00 P. M., Tuesday, April 21, 1942, or during the same hours on Wednesday, April 22, 1942, to the Civil Control Station located at:

2422 Lincoln Boulevard

Santa Monica, California3. Any person subject to this order who fails to comply with any of its provisions or with the provisions of published instructions pertaining hereto or who is found in the above area after 12 o'clock noon, P.W.T., of Tuesday, April 28, 1942, will be liable to the criminal penalties provided by Public Law No. 503, 77th Congress, approved March 21, 1942, entitled "An Act to Provide a Penalty for Violation of Restrictions or Orders with Respect to Persons Entering, Remaining in, Leaving, or Committing any Act in Military Areas or Zones," and alien Japanese will be subject to immediate apprehension and internment.

J. L. DeWitt

Lieutenant General, U. S. Army CommandingFigure 1: Civilian Exclusion Order No. 7.

PROHIBITED AREA

EXCLUSION ORDER NO.7

WESTERN DEFENSE COMMAND AND FOURTH ARMY>

This map is prepared the convenience of the public; see the Civilian Exclusion Order for the full and correct description.

Figure 2: Prohibited Area Order No. 7.

WESTERN DEFENSE COMMAND AND FOURTH ARMY

WARTIME CIVIL CONTROL ADMINISTRATION

Presidio of San Francisco. CaliforniaINSTRUCTIONS

TO ALL PERSONS OF

JAPANESE

ANCESTRY

LIVING IN THE FOLLOWING AREA:All that portion of the County of Los Angeles, State of California, within the boundary beginning at the point where the Los Angeles-Ventura County line meets the Pacific Ocean; thence northeasterly along said county line to U. S. Highway No. 101; thence easterly along said Highway No. 101 to Sepulveda Boulevard; thence southerly along Sepulveda Boulevard to Wilshire Boulevard; thence westerly on Wilshire Boulevard to the limits of the City of Santa Monica; thence southerly along the said city limits to Pico Boulevard; thence easterly along Pico Boulevard to Sepulveda Boulevard; thence southerly on Sepulveda Boulevard to Manchester Avenue; thence westerly on Manchester Avenue and Manchester Avenue extended to the Pacific Ocean; thence northwesterly across Santa Monica Bay to the point of beginning.

Pursuant to the provisions of Civilian Exclusion Order No. 7, this Headquarters, dated April 20, 1942, all persons of Japanese ancestry, both alien and non-alien, will be evacuated from the above area by 12 o'clock noon, P.W.T., Tuesday, April 28, 1942.

No Japanese person living in the above area will be permitted to change residence after 12 o'clock noon, P.W.T., Monday, April 20, 1942, without obtaining special permission from the representative of the Commanding General, Southern California Sector at the Civil Control Station located at:

2422 Lincoln Boulevard

Santa Monica, CaliforniaSuch permits will only be granted for the purpose of uniting members of a family, or in cases of grave emergency.

The Civil Control Station is equipped to assist the Japanese population affected by this evacuation in the following ways:

1. Give advice and instructions on the evacuation.

2. Provide services with respect to the management, leasing, sale, storage or other disposition of most kinds of property, such as real estate, business and professional equipment, household goods, boats, automobiles and livestock.

3. Provide temporary residence elsewhere for all Japanese in family groups.

4. Transport persons and a limited amount of clothing and equipment to their new residence.

THE FOLLOWING INSTRUCTIONS MUST BE OBSERVED:

1. A responsible member of each family, preferably the head of the family, or the person in whose name most of the property is held, and each individual living alone, will report to the Civil Control Station to receive further instructions. This must be done between 8:00 A. M. and 5:00 P. M. on Tuesday, April 21, 1942, or between 8:00 A. M. and 5:00 P. M. on Wednesday, April 22, 1942.

2. Evacuees must carry with them on departure for the Reception Center, the following property:

(a) Bedding and linens (no mattress) for each member of the family;

(b) Toilet articles for each member of the family;

(c) Extra clothing for each member of the family;

(d) Sufficient knives, forks, spoons, plates, bowls and cups for each member of the family;

(e) Essential personal effects for each member of the family.

All items carried will be securely packaged, tied and plainly marked with the name of the owner and numbered in accordance with instructions obtained at the Civil Control Station. The size and number of packages is limited to that which can be carried by the individual or family group.

3. No pets of any kind will be permitted.

4. The United States Government through its agencies will pro vide for the storage at the sole risk of the owner of the more substantial household items, such as iceboxes, washing machines, pianos and other heavy furniture. Cooking utensils and other small items will be accepted for storage if crated, packed and plainly marked with the name and address of the owner. Only one name and address will be used by a given family.

5. Each family and individual living alone will be furnished transportation to the Reception Center. Private means of transportation will not be utilized. All instructions pertaining to the movement will be obtained at the Civil Control Station.

Go to the Civil Control Station between the hours of 8:00 A. M. and 5:00 P. M., Tuesday, April 21, 1942, or between the hours of 8:00 A. M. and 5:00 P. M., Wednesday, April 22, 1942 to receive further instructions.

J. L. DeWitt

Lieutenant General, U. S. Army CommandingFigures 3-4: Instructions to All Persons of Japanese Ancestry pages 2-3.

On March 6, 1942, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, acting as the agent of the Treasury Department, was given responsibility for handling the urban property problems of the evacuees, and an Alien Property Custodian was appointed on March 11. [61] Four days later, the Farm Security Administration assumed responsibility for assisting with farm property questions. The Federal Security Agency, through its various associated agencies, agreed to provide necessary social services. Each of these agencies had representatives at the 48 WCCA civil control stations to facilitate the early initiatives for voluntary migration, and although voluntary migration from Military Area No. 1 formally ended on March 29 each agency retained its obligation under the direction of the WCCA by staffing the civil control stations in the exclusion areas until the WRA assumed total responsibility for the evacuees in August 1942. [62]

By that time, however, many abuses had already been committed. Vulnerable to opportunists, the evacuees were subjected to droves of people who came to purchase goods and to take advantage of the availability of household furnishings, farm equipment, automobiles, and merchandise at bargain prices. [63] The Tolan Committee provided a succinct example of what it had discovered:

A typical practice was the following: Japanese would be visited by individuals representing themselves as F.B.I. agents and advised that an order of immediate evacuation was forthcoming. A few hours later, a different set of individuals would call on the Japanese so forewarned and offer to buy up their household and other equipment. Under these conditions the Japanese would accept offers at a fraction of the worth of their possessions. Refrigerators were thus reported to have been sold for as low as $5. [64]

Property and business losses also arose from confusion among government agencies. The military's delay in providing reasonable and adequate property protection and its failure to provide warehouses or other secure structures contributed to initial evacuee losses. Confusion existed among the Federal Reserve Bank, the Farm Security Administration, and the Office of the Alien Property Custodian. Not only did each agency have different policies, but there was also confusion within each how to implement its program. Dillon S. Myer, a Department of Agriculture official who replaced Eisenhower as director of the WRA on June 17, 1942, after the latter became Deputy Director of the Office of War Information, decried the result of the government's efforts to protect the evacuees' property:

The loss of hundreds of property leases and the disappearance of a number of equities in land and buildings which had been built up over the major portion of a lifetime were among the most regrettable and least justifiable of all the many costs of the wartime evacuation. [65]

In general, the Japanese evacuees were encouraged to take care of their own goods and their own affairs. Given the immense difficulties of protecting the diverse economic interests of more than 100,000 people, it is not surprising that despite the government's offer of aid it relied primarily on the evacuees to care for their own interests. At the same time, it is not surprising that, facing the distrust expressed in the government's exclusion and evacuation policies, most evacuees wanted to do what they could for themselves. [66] Economic losses from the evacuation were substantial for the Japanese. Owners and operators of farms and businesses either sold their income-producing assets under distress-sale circumstances on very short notice or attempted, with or without government help, to place their property in the custody of Caucasian friends or other people remaining on the coast. The effectiveness of these measures varied greatly in protecting evacuees' economic interests. Homes had to be sold or left without the personal attention that owners would devote to them. Businesses lost their good will, reputation, and customers. Professionals had their careers and practices disrupted. Not only did many suffer major losses during evacuation, but their economic circumstances deteriorated further while they resided in assembly and relocation centers during the war. The years of exclusion were frequently punctuated by financial troubles as the Japanese attempted to look after property without being on the scene when troubles arose, and they lacked a source of income to meet tax, mortgage, and insurance payments. Goods were lost or stolen during the war years, and the income and earning capacity of the excluded Japanese were reduced to almost nothing during the lengthy detention in relocation centers. [67]

SECOND STAGE OF EVACUATION

On June 2, 1942, a second stage of the government's Japanese evacuation program began when, by Public Proclamation No. 6, DeWitt ordered the exclusion of Japanese aliens and American citizens of Japanese ancestry from the California portion of Military Area No. 2 on the grounds of military necessity. [68] This order left undisturbed those Japanese then living in eastern Oregon and Washington, southern Arizona, and in other states of the Western Defense Command — except as DeWitt applied to them his new authority to exclude suspected individuals from sensitive areas. The first civilian exclusion order [No. 100] for this area was issued on June 27, and by August 8 all persons of Japanese ancestry had been removed from the eastern part of California. In all, 9,337 evacuees were encompassed in Civilian Exclusion Orders Nos. 100-08. This final phase of the mass evacuation was carried out by direct movements from places of residence to relocation centers. More than half of these were Japanese who had moved voluntarily, with the encouragement of the military, into the interior of California from Military Area No. 1, the majority of whom moved on the two days between the issuance of the "freeze order" [Public Proclamation No. 4] of March 27 and its effective date of March 29. [69]

The exclusion from the California portion of Military Area No. 2 appears to have been decided without any additional evidence of threat or danger in the area. The aforementioned War Department's Final Report observed:

Military Area No. 2 in California was evacuated because (1) geographically and strategically the eastern boundary of the State of California approximates the easterly limit of Military Area No. 1 in Washington and Oregon . . . and because (2) the natural forests and mountain barriers, from which it was determined to exclude all Japanese, lie in Military Area No. 2 in California, although these lie in Military Area No. 1 of Washington and Oregon. [70]