|

MANZANAR

Historic Resource Study/Special History Study |

|

CHAPTER FOUR:

ASSEMBLY CENTERS UNDER THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE WARTIME CIVIL CONTROL ADMINISTRATION

Compulsory mass evacuation began on March 30, 1942. Until August 8, groups of Japanese left their homes for assembly centers, directed by one of the 108 civilian exclusion orders. The WCCA attempted, not always successfully, to place people in centers close to their homes. Sixteen assembly centers (a list of the centers and their average population, total days occupied, dates of occupancy, and maximum population may be seen on the following page) were established by the WCCA to provide temporary facilities for the Japanese evacuees before they would be transferred to permanent relocation centers. Thirteen of the centers were in California, one (Puyallup) was in Washington, one (Portland) was in Oregon, and one (Mayer) was in Arizona. The thirteen centers in California included Marysville, Sacramento, Tanforan, Stockton, Turlock, Salinas, Merced, Pinedale, Fresno, Tulare, Santa Anita, Pomona, and Manzanar. Two of the assembly center sites were converted race tracks (Santa Anita and Tanforan), one was a rodeo ground (Salinas), and nine were fairgrounds (Marysville, Stockton, Turlock, Merced, Fresno, Tulare, Portland, Puyallup, and Pomona). [1]

As mentioned in Chapter 3 of this study, the Manzanar and Poston (officially designated the Colorado River Relocation Center) assembly centers were intended initially as "reception centers." They were to be operated by the Army during the initial phases of evacuation. Manzanar remained under the administration of the WCCA (and thus functioned generally as an assembly center) from its opening in mid-March until June 1, 1942, when it was transferred to the War Relocation Authority for use as a permanent relocation center. In June, Mayer was closed down, and its inhabitants were transferred to Poston, a WRA-operated relocation center established on a former Arizona Indian reservation. Direct evacuation to both of these centers was substantial. In the War Department's Final Report, DeWitt observed that 9,830 evacuees were moved directly to Manzanar. and 11,711 were evacuated directly to Poston, thus eliminating the need for additional assembly center capacity. [2]

ASSEMBLY CENTERS

Assembly centers were planned for use for short periods of time, their sole purpose being to serve as points of concentration and confinement until the War Relocation Authority could establish permanent relocation centers. Because of wartime difficulties in construction and transportation, as well as a shortage of building materials, however, the period of assembly center operation extended for approximately seven and one-half months. The assembly center operations program extended for 224 days from the opening of Manzanar on March 21 to the closing of Fresno on October 30. Exclusive of Manzanar. the Santa Anita Assembly Center, located at a racetrack in Los Angeles, had the longest period of occupancy and the largest number of residents — 215 days with an average population of 12,919. During much of this period, the population of Santa Anita was more than 18,000. [3] Next in order of length of evacuee occupancy were Fresno, 178 days; Tanforan, 169 days; and Stockton, 161 days. On the other hand, the center at Mayer was closed after 27 days, Sacramento after 52 days, Marysville after 53 days, Salinas after 69 days, and Pinedale after 78 days. [4]

| Center | Average population |

Total days occupied |

DATES OF OCCUPANCY |

MAXIMUM POPULATION | ||

| From | To | Number | To | |||

| Fresno Manzanar (1) Marysville Mayer Merced Pinedale Pomona Portland Puyallup Sacramento Salinas Santa Anita Stockton Tanforan Tulare Turlock |

4,403 5,186 1,760 214 3,762 3,690 4,735 2,969 5,704 3,190 3,032 12,919 3,725 6,501 4,112 2,888 |

178 72 53 27 133 78 110 132 137 52 69 215 161 169 138 105 |

5-6 3-21 5-8 5-7 5-6 5-7 5-7 5-2 4-28 5-6 4-27 3-27 5-10 4-28 4-20 4-30 |

10-30 5-31 6-29 6-2 9-15 7-23 8-24 9-10 9-12 6-26 7-4 10-27 10-I7 10-13 9-4 8-12 |

5,120 9,666 2,451 245 4,508 4,792 5,434 3,676 7,390 4,739 3,594 18,719 4,271 7,816 4,978 3,662 |

9-4 5-31 6-2 5-25 6-3 6-29 7-20 6-6 5-25 5-30 6-23 8-23 5-21 7-25 8-11 6-2 |

Figure 5: U.S. War Department, Final Report, p. 227.

CONSTRUCTION AND FACILITIES

In the War Department's Final Report, DeWitt observed that the sites selected for assembly centers "proved to be reasonably adequate for the purpose." He noted that the original intention "was to house evacuees in Assembly Centers for a much shorter period than that which proved to be the case." For "extended occupancy by men, women, and children whose movements were necessarily restricted, the use of [hastily constructed cantonment-type] facilities of this character" was "not highly desirable." However, there was, according to the general, "no alternative." "Modifications and additions effected during the course of operations," according to DeWitt, "tended largely to overcome the natural disadvantages inherent in the confinement of a large community within a limited area." DeWitt noted that assembly center construction by the Corps of Engineers

generally followed those specifications established for Army cantonments. Of course, numerous refinements were included adequately to provide for the housing of family units. Considerable augmentation was essential because of the necessity for providing separate utilities for men and for women and children. [5]

In most cases, adaptive use of existing structures at the assembly centers was limited, being used primarily as warehouse facilities, offices, infirmaries, or large mess halls. Some buildings, however, were utilized for evacuee work projects, schools, repair shops, and recreational activities.

Although a few existing buildings were modified for use as living quarters, apartment space was largely provided through new construction. The type of buildings erected for this purpose was substantially uniform. Theater of operations type barracks with suitable floors, ceilings, and partitions were built at most centers, Where possible, living quarters were grouped in blocks, each having showers, lavatories, and flush toilet facilities. Generally, blocks consisted of fourteen barracks. The capacity of each block varied, but the norm was between 600 to 800 persons. In the larger centers, there were up to 48 blocks. Where practicable, a kitchen and mess hall were provided for each block, In some centers, notably Santa Anita, Tanforan, and Portland, existing facilities were adapted for use as mess halls in which larger groups of evacuees were fed at a single facility At Santa Anita, for instance, the 25-acre camp was divided into seven sections, each with a post office, a store, a mess hall, and showers. [6]

Although most assembly centers were located at fairgrounds or racetracks, their design and construction varied. In Portland's Pacific International Livestock Exposition Pavilion, for instance, virtually all the evacuees were housed under one roof because the pavilion covered 11 acres and provided living quarters for 3,800 people. Puyallup had four separate housing areas — three were originally parking lots and one was the fairground itself. At Santa Anita and Tanforan, the stable areas were renovated and modified to provide "apartment" space.

Where existing structures Were inadequate to provide housing for community services, DeWitt noted that new buildings were built. At Tanforan, for instance, 169 new buildings were constructed. Infirmaries, each with a laboratory, surgical room, and kitchen, were established at each of the smaller assembly centers, and, in the larger centers, hospitals were constructed. Laundries, equipped with stationary wash tubs and ironing boards, canteens, post offices, dental clinics, barber shops, warehouses, administration buildings, recreation halls, and reception areas were built or created by adaptation of existing buildings. Hot water was initially in short supply at most assembly centers, but this "deficiency" was soon "augmented." Play fields, recreational halls, and fire stations were equipped "with the necessary items." [7]

Housing for military police at each center was provided in an area separate from the assembly center "barbed-wire" enclosure for the detainees, Where existing accommodations could not be adapted for this purpose, barracks were constructed as were "auxiliary installations." Although DeWitt claimed that these facilities were ordinarily "similar to those used by evacuees," there is evidence that facilities for the military police were more substantial than those for the evacuees.

Following transfer of the evacuees to the WRA-directed relocation centers, assembly center facilities were occupied by various Army units, most serving "as service schools for the various Army branches, such as ordnance, signal corps, quartermaster and transportation corps." DeWitt noted that the assembly centers were "more ideally suited for troop use than they were for the housing of families." [8]

WCCA policy allotted a 10-foot x 20-foot space (200 square feet) per married couple. Family groups inside the centers were to be kept together, and families would share space with others only if it were unavoidable. To meet these needs, units were to be remodeled if necessary, and each was to be furnished with "standard Army steel cots," mattresses, blankets (a minimum of three per person), and pillows. Each unit was to have electrical outlets. However, the speed of evacuation and the shortages of labor and building materials, such as lumber, meant that living arrangements did not always conform to WCCA policy. At Tanforan, for instance, bachelors who did not live in the renovated stables occupied a huge dormitory under the racetrack grandstand, an enormous room with 350 to 400 beds along one wall with less than two feet between each bed. [9]

Despite the problems associated with the sites and facilities at the assembly centers, the Red Cross representative who visited the centers at the Army's request concluded, taking into account his own experience in housing large numbers of refugees, that as a whole the evacuees were "comfortably and adequately sheltered." He stated:

Generally, the sites selected were satisfactory with the possible exception of Puyallup, where lack of adequate drainage and sewage disposal facilities created a serious problem. . . In studying the housing facilities in these centers, it is necessary to keep in mind that the job was without precedent, and that the sites were selected and buildings completed in record-breaking time in the face of such handicaps as material and labor shortages and transportation difficulties. [10]

ADMINISTRATION

Following establishment of the WCCA, R. L. Nicholson, then regional director of the Works Projects Administration for the eleven western states, was appointed in mid-March as its Chief, Assembly Center Branch of the Temporary Settlement Operations Division. As the operations of the Works Projects Administration, a large-scale national works program that had been established during the Depression for jobless employables, were being phased out as a result of the emerging war economy, large numbers of its field staff were available for other employment. As a result, Nicholson. who took a temporary leave of absence from the WPA to aid the evacuation program, facilitated the "transfer" of many former WPA personnel, who had considerable experience in federal fiscal, procurement, and administrative policy and procedures, to provide administrative staff for the assembly centers. The responsibility for assembly center operations, however, remained with DeWitt whose "administrative directions were carried into effect through" Colonel Bendetsen, the WCCA director, from the agency's headquarters in the Whitcomb Hotel in San Francisco. [11]

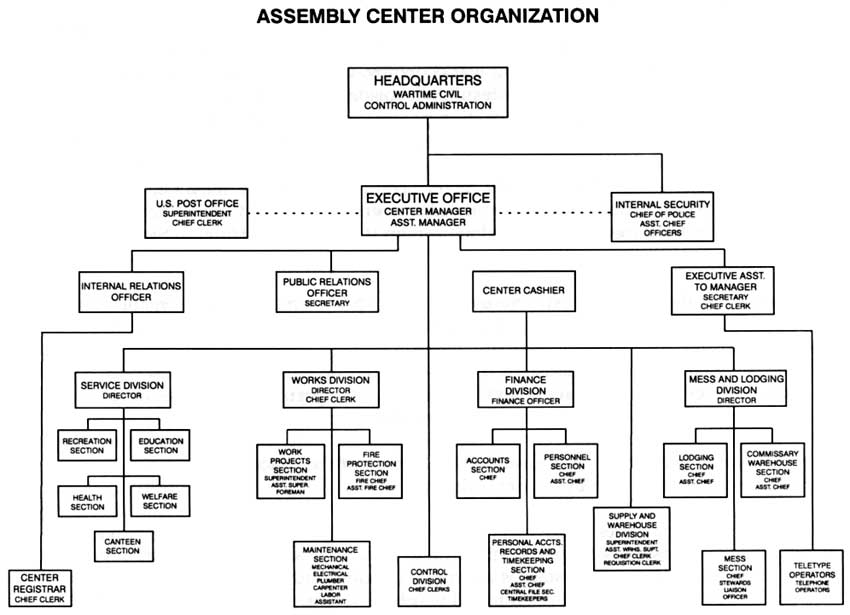

The "executive" organizational structure (A copy of an "Assembly Center Organization" chart may be seen on the following page) in the assembly centers included a manager and assistant manager under whom were an internal relations officer, public relations officer, center cashier, and executive assistant. There were four operating divisions: service, works, finance, and mess/lodging. Caucasian staff were a class apart: their quarters were generally located in a separate, guarded section outside the barbed-wire center enclosure. Even where the staff quarters were not rigidly separated from the rest of the center, they were noticeably better built and furnished than those of the evacuees. Fraternization with the Japanese was forbidden by written rule. [12]

U.S. postal service facilities were operated in the assembly centers by regular, bonded postal employees assigned by postal authorities. They were authorized to carry on normal postal services, such as selling stamps and money orders and handling parcel post packages. They were also authorized to sell war bonds. Evacuees sorted and delivered incoming and outgoing mail. Although such mail was not censored, parcel post packages were inspected for contraband "in the presence of the addressee." Banking facilities were provided in all assembly centers, although banking by mail was encouraged through the assistance of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. [13]

The U.S. Public Health Service was responsible for the immediate direction of center infirmaries, hospitals, and outpatient services. Evacuee doctors and nurses were recruited to staff the medical facilities. An evacuee physician in each center was designated as chief medical officer and dealt directly with the management. [14]

Soon after the selection of the assembly center sites, the WCCA issued an Operation Manual to provide administrative guidance for the centers' operation. Periodically updated, the manual, according to DeWitt, "covered all aspects of operations, and prescribed the rules to be observed by evacuees in the interests of public health, morals and order." Regulations were posted for the "information and guidance of those affected. [15]

ASSEMBLY CENTER ORGANIZATION

|

|

Figure 6: Assembly Center Organization U.S. War Department, Final

Report, p. 223. (click on the above image for an enlargement in a new window) |

SECURITY

The commanding generals of each sector of the Western Defense Command were responsible to DeWitt for the external security at each of the assembly centers. One or more military police companies were assigned to each assembly center "as required by the area and evacuee population involved.

The basic function of the military police at the assembly centers was to guard the camp perimeters and to "prevent ingress and egress of unauthorized persons [without passes issued by the WCCA]." According to the Operation Manual, the assembly centers were "generally located in grounds surrounded by fences clearly defining the limits for evacuees." In centers "having no fences, and boundaries marked only by signs, the military police" were to "control the roads leading into the Center and may have sentry towers placed to observe the evacuee barracks," The "balance of the area could "be covered by motor patrol." [16] If an evacuee attempted to leave camp without permission, he would be halted, arrested, and delivered to the center internal civilian police. A "firm but courteous" attitude toward the evacuees was required, but the military police were not permitted to fraternize with them. The military police were permitted within the areas occupied by the evacuees only when performing their prescribed duties. In the event of a fire, riot, or disorder which was beyond the control of center management or its internal police, assembly center officials were authorized to call for assistance from the military police. When they were called, the "commanding officer assumed full charge of the entire Center until the emergency was ended." The commanding officer of the military police was responsible for black-outs of the centers, and a switch was to "be so located to permit the prompt cut-off by the military police of all electric current in the center." The military police were also responsible for protection of merchandise at the post exchanges furnished for the use of the military personnel.

Original plans for internal security at each center contemplated a civilian law enforcement body consisting of an experienced Caucasian peace officer as chief of police and one other Caucasian assistant, with evacuees to serve as patrolmen. Early in the operation of the first centers, "disaffection among the evacuees" became "rampant," necessitating a change in plans. An Interior Security Branch was established in the central office of the WCCA, and an army officer with previous experience as a student of municipal affairs and as a metropolitan police chief was assigned as chief. Caucasian civilians with municipal police experience were employed as assistant chiefs of the branch, inspectors, and planning assistants. An experienced municipal police officer, directly responsible to the WCCA, was employed as chief of interior security police in each center. An assistant chief and two or more sergeants rounded out his Caucasian staff. A number of patrolmen were recruited from the evacuee population. The proportion of interior security police was four per one thousand evacuee population. Duties of the internal security police, as governed by an Interior Security Manual, included inspection of all incoming and outgoing parcels, except letter mail, for contraband; inspection of all vehicles passing through entrances and exits; supervision of visitors; patrol of mess halls; and escort of all evacuees who were authorized by the center manager to leave the center. The personnel of the Interior Security Branch reached its maximum in the month of July 1942 with a total of 334 employees — 319 in the assembly centers and 15 in the WCCA headquarters.

Charges for criminal offenses in the assembly centers totaled 534 between April 25 and October 25, 1942. The largest categories of offenses were larceny (theft), 123; "suspicion," 117; disorderly conduct, 72; gambling, 55; and assault, 36.

To assist in keeping the peace and regulating foot and motorized traffic during the early operations of the assembly centers, the chiefs of internal security recruited staffs of auxiliary police from among evacuees. This practice, according to DeWitt, "proved wholly unsuccessful." Their alleged "transgressions" included extending special privileges to influential evacuees, demanding extra compensation and privileges, protecting gambling rings, and participating in demonstrations and disturbances. Thus, after "more than a fair trial," the evacuee auxiliaries were disbanded.

Direct liaison was established between the internal security police at each center and local law enforcement agencies, county attorneys, and courts. All internal security police at each center received deputizations from local county sheriffs except in those cases where the center was entirely within a municipality. There special police commissions were issued by local police chiefs. Violations of local ordinances and state laws were tried in local courts before local prosecutors.

Subversive activities and violations of federal laws were investigated by the FBI and prosecuted in the federal courts. Internal security police conducted preliminary investigations, reported those that appeared to be federal violations to the FBI, and cooperated with FBI agents in further investigations and the apprehension of violators. [17]

EVACUEE EXPERIENCES

The evacuees endured the frustrations and inconveniences of the assembly centers for the most part peacefully and stoically. The experiences of many evacuees, however, contributed to and reinforced their sense of bitterness, hopelessness, and despair — attitudes they would take with them to the relocation centers.

Transfer to Assembly Centers

Once a civilian exclusion order was posted in an area to be evacuated, a representative of each family was directed to visit a civilian control station where the family was registered and issued a number that was to be appended to each piece of baggage and coat lapel of each family member. The representative was told when and where the family should report and what belongings could be taken. Baggage restrictions posed a problem, because most evacuees did not know their ultimate destination. They could only take what they could carry, a stipulation that created considerable anguish as one's lifetime possessions were sorted.

On departure day, the evacuees, wearing tags and carrying their baggage, gathered in groups of about 500 at an appointed spot. Although some were allowed to take their automobiles, traveling in military-escorted convoys to the assembly centers, most made the trip by bus or train. The WCCA made an effort to foresee problems during the journey. Ideally each group was to travel with at least one doctor and a nurse, as well as medical supplies and food. One of every four seats on the conveyance was to be vacant to hold hand luggage. The buses were to stop as necessary, and persons who might require medical assistance would be clustered in one bus or train car with the nurse.

Despite such planning, many evacuees experienced less than ideal conditions on their trips to the assembly centers. In some cases, there was little or no food on long trips. Sometimes train windows were blacked out, aggravating the evacuees' feelings of uncertainty and heightening their sense of isolation and abandonment. The sight of armed guards patrolling the trains and buses was not reassuring. One evacuee, for instance, later recalled her trip to an assembly center:

On May 16, 1942 at 9:30 a.m., we departed . . . for an unknown destination, To this day [August 6, 1981], 1 can remember vividly the plight of the elderly, some on stretchers, orphans herded onto the train by caretakers, and especially a young couple with 4 pre-school children. The mother had two frightened toddlers hanging on to her coat. In her arms, she carried two crying babies. The father had diapers and other baby paraphernalia strapped to his back. In his hands he struggled with duffle bag and suitcase. The shades were drawn on the train for our entire trip. Military police patrolled the aisles. [18]

Many evacuees recall two images of their arrival at the assembly centers. One was walking to the camp between a cordon of armed military guards with bared bayonets, and the other was first seeing the barbed wire, watchtowers, and searchlights surrounding the camp. Leonard Abrams, a member of a Field Artillery Battalion that guarded the Santa Anita Assembly Center, later recounted:

We were put on full alert one day, issued full belts of live ammunition, and went to Santa Anita Race Track. There we formed part of a cordon of troops leading into the grounds; busses kept on arriving and many people walked along . . .many weeping or simply dazed, or bewildered by our formidable ranks. [19]

For many evacuees, arrival at the assembly center brought the first vivid realization of their condition. They were under military guard and considered possible threats to the national security of the nation. One evacuee later recalled his entry into the Tanforan Assembly Center at San Bruno, California:

At the entrance . . . stood two lines of troops with rifles and fixed bayonets pointed at the evacuees as they walked between the soldiers to the prison compound. Overwhelmed with bitterness and blind with rage, I screamed every obscenity I knew at the armed guards daring them to shoot me. [20]

Once inside the gates of the assembly center, the evacuees were searched, fingerprinted, interrogated, given a cursory medical examination, and inoculated. After the preliminaries, Caucasian administrators compiled a lengthy social and occupational history of each arrival and explained the rules of the camp. Following these preliminaries, assembly center staff or selected Nisei directed the evacuees to their assigned quarters. Each family was presented with a broom, mop, and bucket for most of the camps were extremely dusty. Arrivals were handed long bags of mattress ticking containing straw, a method of mattressing the cots. Most new arrivals stuffed their own casings with straw, making not too uncomfortable beds at first — before they began to mat down and turn to dust, requiring them to be refilled every few weeks. [21]

Many of the evacuees typically reacted to their initial encounters at the assembly centers with feelings of bewilderment, insecurity, and apprehension. Red Cross representatives who visited the assembly centers described some evacuees' reactions soon after arrival:

Many families with sons in the United States Army and married daughters living in Japan are said to feel terrific conflict. Many who consider themselves good Americans now feel they have been classed with the Japanese. . . . There is a great financial insecurity. Many families have lost heavily in the sale of property. . ..Savings are dipped into for the purchase of coupon books to be used at the center store, and with the depletion of savings comes a mounting sense of insecurity and anxiety as to what will be done when the money is gone. . . . Doubtless the greatest insecurity is that about post-war conditions. Many wonder if they will ever be accepted in Caucasian communities. [22]

Housing and Facilities

During the hearings of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in 1981, evacuees described typical living arrangements that were well below the WCCA's spartan standards. Among the reminiscences were the following:

Pinedale. The hastily built camp consisted of tar paper roofed barracks with gaping cracks that let in insects, dirt from the . . . dust storms . . . no toilet facilities except smelly outhouses, and community bathrooms with overhead pipes with holes punched in to serve as showers. The furniture was camp cots with dirty straw mattresses. [23]

Puyallup. This was temporary housing, and the room in which I was confined was a makeshift barracks from a horse stable. Between the floorboards we saw weeds coming up. The room had only one bed and no other furniture. We were given a sack to fill up with hay from a stack outside the barracks to make our mattresses. [24]

Portland. The assembly center was the Portland stockyard. It was filthy, smelly, and dirty. There was roughly two thousand people packed in one large building. No beds were provided, so they gave us gunny sacks to fill with straw, that was our bed. [25]

Santa Anita. We were confined to horse stables. The horse stables were whitewashed. In the hot summers, the legs of the cots were sinking through the asphalt. We were given mattress covers and told to stuff straw in them. The toilet facilities were terrible. They were communal, There were no partitions. Toilet paper was rationed by family members. We had to, to bathe, go to the horse showers. The horses all took showers in there, regardless of sex, but with human beings, they built a partition.... The women complained that the men were climbing over the top to view the women taking showers. [When the women complained] one of the officials said, are you sure you women are not climbing the walls to look at the men. . . . [26]

It had extra guard towers with a searchlight panoraming the camp, and it was very difficult to sleep because the light kept coming into our window . . . I wasn't in a stable area, . . . [but] everyone who was in a stable area claimed that they were housed in the stall that housed the great Sea Biscuit. [27]

Barracks at most assembly centers were constructed of rough green lumber. These thin pine boards buckled and separated, and large spaces grew between them. The tar paper glued on the outside of the barracks did not keep the searchlights from shining between the boards at night. Doors might or might not fit the openings meant for them. Floors made of the same raw lumber developed cracks between the boards, although in some camps the government eventually laid linoleum. Cold entered the cracks at night and dust in the daytime.

A typical single family unit had one window that looked out on the street. Some quarters had no windows at all, while an exceptional room, such as some at Pomona, had three windows. There were no shades or curtains except when people were able to find goods with which to make them, no shelves, closets, or lockers, and to keep their places neat evacuees often stored their belongings under the beds.

Evacuees began immediately to improve their quarters, busying themselves scrubbing down floors and putting away their belongings. Water had to be hauled a long way as the block laundry rooms and mess halls were generally a good distance off. Water from these sources was cold as often as warm. Victory gardens were planted beside the barracks, and Tanforan evacuees built a miniature aquatic park with bridge, promenade, and islands. [28]

Among the most severe discomforts experienced by the evacuees at the assembly centers were overcrowding and lack of privacy. Despite WCCA planning, eight-person families were sometimes placed in 20-foot by 20-foot rooms, six persons in 12-foot by 20-foot rooms, and four persons in 8-foot by 20-foot rooms. If families were small, other persons were often moved in with them. Extra children might be housed next door. Several married couples sometimes were forced to share a single room, their quarters separated by sheets hung on wires across the room. Partitions between apartments did not provide much privacy, for many did not extend up to the roof, and conversations on the other side were necessarily overheard. Latrines were not properly partitioned, and it frequently took considerable protest by the evacuees to get the authorities to have appropriate partitions and shower curtains installed. [29] One evacuee, for instance, wrote from the Merced Assembly Center:

. . . the only thing I really don't like are the lavatories. It's not very sanitary and has caused a great deal of constipation in camp for both men and women. The toilets are one big row of seats, that is, one straight board with holes out about a foot apart with no partitions at all and all the toilets flush together. . . . about every five minutes. The younger girls couldn't go to them at first until they couldn't stand it any longer, which is really bad for them. [30]

The weather often made conditions oppressive in the assembly centers. On hot days, overcrowding and sewage problems made the heat seem unbearable. At Pinedale, for instance, temperatures soared to 110 degrees, and evacuees were given salt tablets to prevent dehydration. [31] At Puyallup, mud posed serious difficulties:

We fought a daily battle with the carnivorous Puyallup mud. The ground was a vast ocean of mud, and whenever it threatened to dry and cake up, the rains came and softened it into slippery ooze. [32]

Family Separation

Many families arrived at the assembly centers with family members missing, thus adding to their demoralized feelings. In some cases, family members, usually the father, had earlier been taken into custody by the FBI. In other instances, family members were institutionalized in sanitoriums, hospitals, or asylums. Those whom the WCCA considered too sick to move, who resided in institutions, or who were in prison, received exemptions or deferments until they were able to travel. As a result, some families arrived with single parents or without a child, and sometimes children arrived without either parent.

Another source of family separation was the WCCA policy defining who was "Japanese." Many individuals of mixed parentage had some Japanese ancestors; others Were Caucasian but married to someone of Japanese ancestry. Many of these people went to assembly centers but had a particularly difficult time, because they were not fully accepted into the community. Those who were allowed to leave often did so.

Some families were separated after they reached the centers, A 17-year-old boy, for instance, was apprehended after sneaking away from Santa Anita to go to the movies. He was sent to a different assembly center and did not see his family again for three years.

Family separation probably occurred most frequently among those who lived in different communities. Grown children were sent to centers different from their parents if they lived in another community. In some cases, exclusion area lines drawn arbitrarily through communities separated family members who lived in different parts of the same Japanese enclave. No visiting privileges, however, were permitted save for exceptional circumstances. [33]

Food, Sanitation, Clothing, and Medical Care

Most of the assembly centers were organized to feed the evacuees in large mess halls. At Santa Anita, for instance, there were three large mess halls where meals were served in three shifts of 2,000 persons each. Where shift feeding was instituted, a system of regulatory badges prevented evacuees from attending the same meal at various mess halls. [34] Lining up and waiting to eat is a memory shared by many:

[W]e stood two hours three times a day with pails in our hands like beggars to receive our meals. There was no hot water, no washing or bathing. It took about two months before we lived half way civilized. [35]

Communal feeding weakened traditional Japanese family ties. At first, families tried to stay together, and some obtained food from the mess hall and took it back to their quarters in order to eat together. In time, however, children began to eat with their friends, leaving many parents to congregate together. [36]

Most evacuees generally agreed that food at the assembly centers left much to be desired, One evacuee recalled that "breakfast consisted of toast, coffee, occasionally eggs or bacon, Then it was an ice cream scoop of rice, a cold sardine, a weeny, or sauerkraut." [37] Another evacuee remembered:

For the first few months our diet. . . . consisted of brined liver — salted liver. Huge liver. Brown and bluish in color . .[that]. . would bounce if dropped. . . . Then there was rice and for dessert, maybe half a can of peach or a pear, tea and coffee. Mornings were better with one egg, oatmeal, tea or coffee. [38]

In time, the kitchens were taken over by evacuee cooks, and culinary style improved, but problems of quality would remain.

Despite the complaints of evacuees, the Red Cross reported that, given the inherent limitations of mass feeding, menus "showed no serious shortages in nutritive values." [39] Many evacuees complained that there was enough milk only for babies and the elderly, thus contradicting the WCCA assertion that "per capita consumption of milk by the population was higher than before evacuation and that it was also higher than that of the American population as a whole." [40] Food problems were aggravated at some centers by a prohibition on importing food into the center. [41]

The WCCA had the same food allowance as that prescribed for the Army — 50 cents per day per person. The assembly centers, however, averaged less than that sum — an average of 39 cents per person per day. The WCCA was very cost conscious in its purchases of foodstuffs since various anti-Japanese elements outside the centers pressed the government to cut expenses even more. [42]

Food became a controversial issue at some assembly centers. At Santa Anita, for instance, a camp staff member was apparently stealing food. A letterwriting campaign began, and, at one point, a confrontation with the military police was narrowly averted when evacuees attempted to halt the car of a Caucasian mess steward whom they believed was purloining food. Following an investigation, the guilty staff member was dismissed. [43]

Assembly center sanitation arrangements were primitive, although the WCCA attempted to minimize health risks by establishing a system of block monitors to inspect evacuee quarters and regular inspections of barracks, showers, and latrines by the assembly center housing supervisor. Food handlers were supposed to undergo physical examinations, and kitchens were to be inspected daily. [44] Nevertheless, shower, washroom, toilet, and laundry facilities were overcrowded, necessitating long waiting lines. The distance to the lavatories, more than 100 yards in some parts of the Puyallup camp, posed a problem for the elderly and families with small children, especially given the muddy conditions. As a result, chamber pots became a highly valued commodity. [45] At some centers temporary plumbing and sewage disposal were problems. On hot days children played "in the shower water that overflowed from the plumbing." [46] An official report of the U.S. Public Health Service concluded that sanitation was bad and the lack of serious epidemics arising from unsanitary conditions in the camps was the result of "heroic efforts of the management of the centers, the County Health Departments and the Japanese Medical staffs." [47]

The Army's own reports testified to the poor sanitation in the assembly centers. For instance, a report prepared by a food consultant and a Quartermaster Corps officer indicated serious sanitary deficiencies:

The kitchens are not up to Army standards of cleanliness. . . . The dishes looked bad . . . gray and cracked. . . . Dishwashing not very satisfactory due to an insufficiency of hot water.., . Soup plates being used instead of plates, which means that the food all runs together and looks untidy and unappetizing. [48]

Securing everyday necessities was difficult for many evacuees. Most had brought their own clothing, but a few, either because of poverty or because they had not anticipated the climate, did not have appropriate clothing. In these cases, upon application, the WCCA provided a clothing allowance of between $25 and $42.19 a year depending on age and gender. The centers had canteens, though often these were poorly supplied. Thus, most evacuees were forced to purchase necessities by ordering from mail order houses. [49]

Inadequate medical facilities and care were among the greatest problems facing the evacuees at the assembly centers, thus adding fear, pain, and inconvenience to their experience. The evacuee doctors and nurses who were recruited by the U.S. Public Health Service found minimal equipment and supplies. At Pinedale, for instance, dental chairs Were made out of crates, and the only instruments were forceps and a few syringes. At Fresno, the hospital was a large room with cots; its only supplies were mineral oil, iodine, aspirin, Kaopectate, alcohol, and sulfa ointment. Some of the doctors who had not brought their instruments were sent home to retrieve them, and all relied, to some extent, on donated supplies. Shortages of medical personnel plagued the assembly centers. At Fresno, for instance, two doctors had to care for 2,500 people. [50]

With few exceptions, medical staff treated the normal range of illnesses and injuries. There were, however, some emergencies. At Fresno, an outbreak of food poisoning affected more than 200 persons, and a similar outbreak occurred at Puyallup. At Santa Anita, hospital records show that about 75 percent of the illnesses came from occupants of the horse stalls. Serious illnesses were treated at nearby hospitals outside the centers, and the Army reported that it paid for such services. Some evacuees, however, recall paying the bills themselves. [51]

Life in the Centers

Because the WCCA had planned only short stays in the assembly centers, they paid little attention to how evacuees would spend their time. As the move to relocation centers was postponed, however, the WCCA and the evacuees attempted to establish a semblance of normal life.

The educational program got off to a slow start but progressed rapidly at most centers, Because evacuation occurred near the end of the school year and the time at the centers was to be temporary, there was no provision in the original plan for schools or educational work. As the assembly centers continued operations into the fall, however, this aspect of life was given increasing attention. [52]

Responding to the needs of the population of the assembly centers, the WCCA belatedly appointed a director of education at each center. This educational supervisor was a member of the center administrative staff, while the education program was under the technical direction of the U.S. Office of Education, Rudimentary classrooms were staffed by evacuee teachers, mostly college graduates. A number of these graduates had been certified, and they were paid $16 per month. School programs varied, At Tanforan, for instance, schools opened late but were well attended — of 7,800 evacuees, 3,650 were students and 100 teachers. At Santa Anita, on the other hand, there was no organized educational program. School furnishings at the assembly centers were "either constructed with evacuee labor or improvised." Progress reports were issued, and work was exhibited, Books and classroom materials, which were often in short supply, were provided primarily through donation from the state and county schools the children had attended prior to evacuation. Supplies arrived sporadically most being the gifts of interested groups and individuals. Instruction was provided for pre-school through high school levels, and adult education classes were also offered at most centers, The curriculum varied, but most traditional subjects were taught in the elementary through high school levels, and adult education offered such subjects as English, knitting and sewing, American history, music, and art. Special classes were held in first aid, safety, fire prevention, and nursing. [53]

Recreational programs were organized cooperatively between the WCCA and the evacuees. Scout troops, musical groups, and arts and crafts classes were formed. Sports teams and leagues for baseball and basketball were established. A calisthenics class at Stockton drew 350 evacuees, Donations helped remedy equipment shortages. Movies were shown regularly at most centers often using donated equipment. At Tanforan, for instance, the mess card served as entrance pass; different nights were reserved for different mess hall groups. Some centers opened libraries to which both evacuees and outside donors contributed. Virtually all centers had some playground area, and some had more elaborate facilities, one even having a pitch-and-putt golf course. [54]

Holidays were cause for celebrations. One evacuee described her preparation for the Fourth of July festivities at Tanforan:

I worked as a recreation leader in our block for a group of 7-10 year old girls. Perhaps one of the highlights was the yards and yards of paper chains we (my 7-10 year old girls) made from cut up strips of newspaper which we colored red, white, and blue for the big Fourth of July dance aboard the ship (recreation hall) dubbed the S.S-6.

These paper chains were the decoration that festooned the walls of the Recreation Hall. It was our Independence Day celebration, though we were behind barbed wire, military police all around us, and we could see the big sign of 'South San Francisco' on the hill just outside of the Tanforan Assembly Center. [55]

Some recreational pursuits, however, were simply traditional pastimes that the evacuees engaged in to while away the time at the assembly centers. Goh and Shogi, Japanese games akin to chess, were popular among the Issei, who ran frequent tournaments and matches, Knitting was a popular pastime among the women. Gambling games were operated, prompting raids and arrests by assembly center police in some cases. [56]

The majority of the evacuees were predominantly Buddhist or Protestant. The WCCA allowed evacuees to hold religious services in designated facilities in the centers and to request assistance from outside religious leaders. Caucasian religious workers were not allowed to live in the centers and could visit only by invitation. The services were monitored for fear they might be used for enemy propaganda or incitement. The use of Japanese was generally prohibited and publications had to be cleared. The prohibition on speaking Japanese created particular problems for the Buddhists, who had few English-speaking priests. Thus, their services were restructured and service books rewritten. [57]

Control of publications extended to the mimeographed center newspapers. Each center had a newspaper, written in English by evacuees under the "guidance of WCCA public relations representatives." News items were generally confined to those determined of "actual interest" to the evacuees. [58]

At some centers, evacuees organized rudimentary forms of self-government. For example, evacuees at Tanforan elected a Center Advisory Council. In August, however, the Army, concerned that such bodies were contributing to evacuee unrest and protest, issued an order dissolving all self-government bodies. [59]

Although no evacuee was required to work, the WCCA planned that assembly center operations be carried out principally by evacuees. Efforts were undertaken to employ evacuees "to the fullest extent practicable on assignments they proved to be capable of performing. Thus, evacuees were employed in virtually every center department, including maintenance and repairs, construction, sanitation, gardening, recreation, education, and services, and some assisted WCCA administrators. Under supervision all kitchens and mess halls were staffed by evacuees. Some 27,000 evacuees, or more than 30 percent of the assembly centers' population, were employed in "necessary and productive" tasks. The average "man-hours per month of those employed equaled 47.7 hours per person of the aggregate evacuee population, non-workers included."

The appropriate payment for evacuee employment was a matter of dispute and a source of continuing dissatisfaction among the evacuee population. At first there was no pay. Eventually evacuees were compensated nominally for work. General DeWitt determined that net cash wages paid to evacuees "should not exceed the net cash allowance then available [$21 for their first four months of service] to any enlisted man in the United States Army." Thus, comparatively low monthly wage rates, based on a 40-hour week, were set at $8 and $12 for unskilled and skilled labor, respectively, and $16 for professionals. [60]

Subsistence, shelter, and medical care, including dental work and hospitalization, were furnished without cost. All evacuees were given a monthly allowance in script or coupons for the purchase of necessities. The monthly coupon allowance was $1 for evacuees under 16 years of age, $2.50 for those over age 16, a maximum of $4.50 for married couples, and a maximum of $7.50 for families, Available community services, such as shoe repair, barber, and beauty shops, were "obtainable in exchange for coupons only." Evacuees were permitted to purchase extra coupon books. [61]

Several assembly centers experimented with establishing enterprises to support the war effort and raise funds to cover the cost of center operations. At Santa Anita, for instance, a camouflage net project produced enough revenue to offset the cost of food for the entire camp. Limited to American citizens because of restrictions imposed by the Geneva Convention, the project attracted more than 800 evacuees. The camouflage net factory was the scene of the only strike in the assembly centers, a sit-down protest over working conditions and insufficient food. At Marysville, in May 1942, a group of evacuees was given leave to thin sugar beets, thus alleviating a labor shortage in the local agricultural sector. This development was exceptional; from most assembly centers, no leave for outside work was permitted. [62]

Security

The military police guarding the perimeters of the assembly centers aroused substantial concern among the evacuees, Armed with machine guns, they appeared menacing. In some cases, they were accused of propositioning or otherwise harassing female evacuees, In general, however, they were rather remote from the life of the centers, entering only at the director's request. The military police, however, had a significant impact on the evacuees in that they signified "the loss and freedom and independence." [63]

According to a study of the assembly centers by the War Relocation Authority community Analysis Section, the "fences, the military police, the searchlights and watchtowers of the centers created a good deal of ill-feeling among the people." "Resentment was high, and in spite of the publicity efforts stating these were not concentration camps, the presence of these fences made this assertion unconvincing." The study stated further:

The crowded conditions and lack of adequate space made the fences seem even closer and more unbearable. After a while, the people became resigned to them, However, they continued to resent the searchlights, especially in those centers in which the guards would play them over the center and flash them into the barracks and on people walking through the area (as reported from Santa Anita), The evacuees hoped and thought that their feeling of restraint and restriction, focused on the psychology of the fences, would be eliminated when they came to the relocation centers. . . . [64]

The evacuees had more encounters and thus more conflict with the internal police in the assembly centers. Internal security measures varied at the centers, but curfews and rollcalls were common. Curfew at Puyallup, for instance, was at 10 p.m., while rollcall at Tanforan was held twice a day at 6:45 A.M. and 6:45 P.M. [65]

Most assembly centers held inspections, designed to search out and seize contraband and prohibited items. The definition of "contraband," however, changed as time went on, causing confusion and resentment, Flashlights and shortwave radios that conceivably could be used for signalling were always contraband. Hot plates and other electrical appliances (often controlled in the interests of fire prevention) were usually contraband, although exceptions were sometimes granted. Alcoholic beverages were forbidden, as were "potentially dangerous" items such as weapons, but the latter category sometimes included knives, scissors, chisels, and saws. At Tulare, inspection sometimes occurred at night, and at Tanforan, one was conducted by the Army, which placed each "section" under armed guard while searching. Evacuees at Puyallup were told to remain in their quarters during search procedures. [66]

Visits to the assembly centers by outsiders were controlled tightly, heightening the evacuees' sense of isolation. Visitors were not allowed "to enter the Center proper or to meet evacuees in their living quarters except in cases of serious illness or other emergency." Visitors could obtain passes to meet evacuees in "visiting houses," through mail application, or at the center gate from an attendant representing center management. [67] Visitors bringing gifts watched packages being opened. Melons, cakes, and pies were cut in half to ensure that none contained weapons or contraband. At some centers, evacuees could converse with visitors only through a wire fence, while others designated special visiting areas, At Tanforan and Pomona, for example, rooms at the top of grandstands were reserved for receiving visitors during specified hours. At Santa Anita, each family was allowed only one visitor's permit a week, and visits were limited to 30 minutes. [68]

According to the aforementioned study by the WRA Community Analysis Section, the "factors in the assembly centers that made the most vivid impressions on the evacuees were fears about the future, the long time spent standing in line for meals, the shame of the entire situation, and the deep feeling of humiliation they experienced because of the 'prison' atmosphere when their Caucasian friends visited them." The "fences around the center made them constantly aware of their status." The study stated further:

The deepest impression on the people was made not so much by the assembly center living conditions as by the sense of restraint, of being fenced in and watched over, of being evacuated from their homes, and by the basic insecurities and anxieties the evacuation had created. Added to this were the fears of the parents that their children were growing up in an artificial environment; that they were not learning the values of the society in which they must adjust and assimilate; and that their education was not comparable to that provided in the communities from which they came... [69]

Evacuees endured the frustrations and inconveniences of the assembly centers for the most part peacefully and stoically. They believed these centers were temporary, and most looked forward to better treatment at the next stop on their evacuation journey — the relocation center.

Although a "nebulous protest movement" developed at many centers, only one major disturbance occurred in the assembly centers. On August 4, 1942, a routine search for various articles of contraband was started after breakfast at Santa Anita. Several internal security police, according to DeWitt, became "over-zealous in their search and somewhat overbearing in their manner of approach to evacuees in two of the Center's seven districts." The evacuees were already upset by an order from the center manager "to pick up, without advance notice, electric hot plates which had previously been allowed on written individual authorization of the Center Management staff to families who needed them for the preparation of infant formulas and food for the sick," Other resentments had been accumulating at the center, including curtailment on reading and possessing Japanese language literature and a ban on Japanese phonograph records.

According to DeWitt, two mobs and a crowd of women evacuees, led in part by some of the evacuee auxiliary police, formed to protest the actions of the internal police and center management. One evacuee long suspected of giving information to the police was beaten, and the internal security police were "harassed" but not injured. Unable to reach the chief of internal security, rumors of other alleged improprieties at the center spread. The military police, armed with tanks and machine guns, were called to quell the disturbance, and the crowds dispersed without further incident. Center management and internal security staff officials responsible for the lack of liaison which allowed the signs of "brewing trouble to reach the boiling point without action" were removed from the center, and the police who had initially precipitated the trouble were replaced. Although this incident was settled without further violence, it, as well as latent protests at other centers, set a pattern that would be repeated with variations in one relocation center after another throughout the war. [70]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

manz/hrs/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2002