|

MANZANAR

Historic Resource Study/Special History Study |

|

CHAPTER FIVE:

RELOCATION CENTERS UNDER THE ADMINISTRATION OF THE WAR RELOCATION AUTHORITY

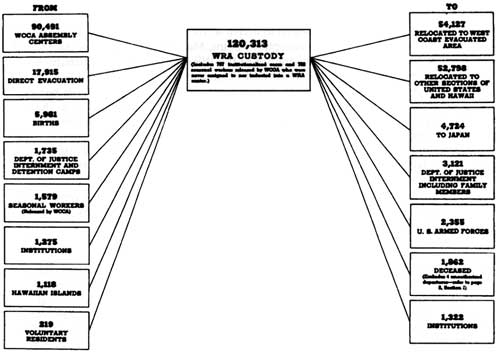

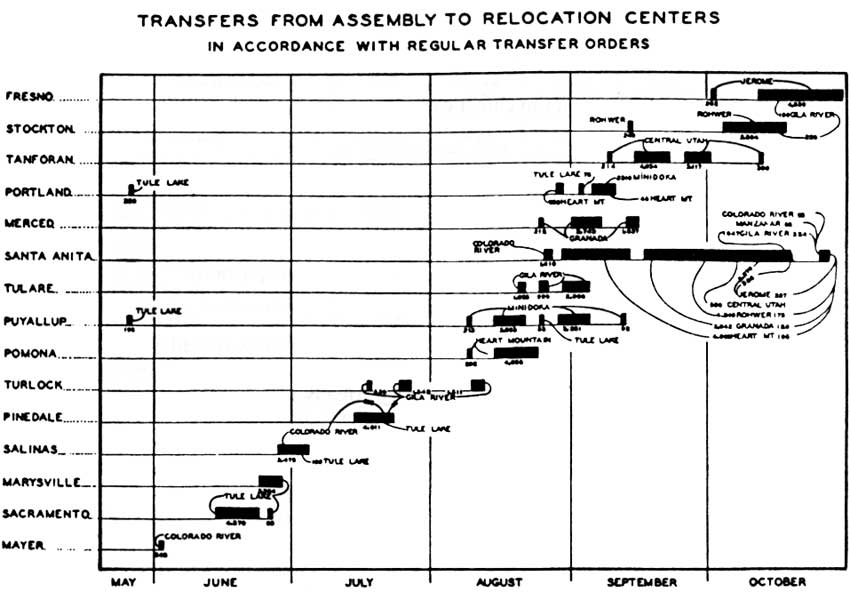

In early May 1942, the first evacuees began to arrive at the relocation centers operated by the War Relocation Authority, the two exceptions being Manzanar (which was transferred from the Wartime Civil Control Administration to the WRA to become an officially-designated relocation center on June 1, 1942) and Poston which had been established initially by the Army as "reception centers" to serve not only as assembly centers but also as permanent relocation centers. By June 5, when the movement of evacuees from their homes in Military Area No. 1 into assembly centers was completed, the transfer of evacuees to relocation centers was well underway. Most entrants to the relocation centers came directly from the WCCA assembly centers, although some arrived from other places, as shown in the chart on the next page. Evacuees had been assured that the WRA centers would be more suitable for residence and more permanent than the hastily-established assembly centers. They also believed that at the new camps some of the most repressive aspects of the assembly centers, particularly the guard towers and barbed wire fences, would be eliminated. All things considered, most evacuees were prepared for an orderly, cooperative move. [1]

Compared with the rapidity of the movement of the Japanese from their homes to the assembly centers, the movement to relocation centers was a lengthy six-month process. [2] By June 30, more than 27,000 people were living at three relocation centers: Manzanar, Poston, and Tule Lake. Three months later, all ten relocation centers except Jerome, Arkansas, had opened, and 90,000 people had been transferred. By November 1, transfers had been completed and, at the end of the year, the centers had the highest population they would ever have — 106,770 persons. More than 175 groups of about 500 each had moved, generally aboard one of 171 special trains, to a center in one of six western states or Arkansas. [3]

WAR RELOCATION AUTHORITY

When evacuees entered a relocation center, they left Army jurisdiction and came into the custody of the War Relocation Authority, a federal agency that had been established by President Roosevelt on March 18, 1942, by Executive Order 9102. Under the provisions of the executive order, the WRA was authorized to formulate and execute a relocation program — to provide shelter, subsistence, clothing, medical attention, educational and recreational facilities, as well as private and public opportunities for evacuees. To implement the WRA program, its director was authorized by the order to

1. Accomplish all necessary evacuation not undertaken by the Secretary of War or military commanders

2. Relocate, supervise, and provide for the needs of such persons

3. Provide for employment of such persons with due regard to the safeguarding of the public interest

4. Secure cooperation and assistance of any governmental agency

5. Consult with the Secretary of War relative to regulations issued by him in order to coordinate evacuation and relocation activities

7. Employ personnel and make expenditures including loans, grants, and the purchase of real property

8. Consult with the U.S. Employment Service and cooperate with the Alien Property Custodian

9. Establish a War Relocation Work Corps to be made up by voluntary enlistment of evacuees

10. Avoid duplication of evacuation activities by not undertaking any evacuation activities within military areas designated under Executive Order 9066 without the approval of the Secretary of War and an appropriate military commander. [4]

|

|

Figure 7: U.S. Department of the Interior, War Relocation Authority.

The Evacuated People: A Quantitative Description (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1946), p. 8. (click on the above image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Milton S. Eisenhower, appointed by President Roosevelt as the WRA's first director, faced a gargantuan task — building an agency to direct and supervise the lives of more than 100,000 people and, at the same time, deciding what to do with them. The WRA had to move quickly in finding centers to house the evacuees and in developing policies and procedures for handling the evacuees soon to come under its jurisdiction. The president had stressed the need for immediate action, and both the War Department and the WRA were anxious to remove the evacuees from the primitive, makeshift assembly centers. Eisenhower quickly concluded that the evacuation would eventually be viewed as "avoidable injustice" and an "inhuman mistake." Eisenhower confronted an initial decision that would shape the rest of the WRA program — would the evacuees be resettled and placed in new homes and jobs, or would they be detained, confined, and supervised for the duration of the war? He was given almost no guidance on this crucial matter. Nothing had been decided beyond the fact that the military would deliver the evacuees to the WRA and thereafter wish no further part in the "Japanese problem." [5]

Eisenhower and his advisors believed that the vast majority of the evacuees were law abiding and loyal and that, once out of the combat zone, they should be returned quickly to conditions approximating normal life. Convinced that the WRA's goal should be to achieve this rehabilitative measure, they devised a plan to move evacuees to the intermountain states. The government would operate "reception centers" and some evacuees would work within them, developing the land and farming. Many more, however, would work outside the centers in private employment — manufacturing, farming, or creating new self-supporting communities. [6]

Mike Masaoka, National Secretary of the Japanese American Citizens League, approached Eisenhower on April 6 with a lengthy letter setting out recommendations and suggestions for policies the WRA should follow. His suggestions were grounded in the basic position that JACL had taken on exclusion and evacuation:

We have not contested the right of the military to order this movement, even though it meant leaving all that we hold dear and sacred, because we believe that cooperation on our part will mean a reciprocal cooperation on the part of the government.

Among the letter's many recommendations was the plea that the government permit Japanese Americans to have as much contact as possible with white Americans to avoid isolation and segregation. [7]

The WRA's plans were in sympathy with such an approach, and on April 2 Eisenhower announced a five-point program for employment of evacuees. The employment program included public works such as land development, agricultural production, and manufacturing within relocation areas, private employment, and private resettlement. [8] However, the government's experience with voluntary relocation suggested that the WRA would only be successful if it could enlist the help of the interior state governors. Accordingly, the WRA arranged a meeting with officials of ten western states for April 7 in Salt Lake City. Representing the federal government were Bendetsen and Eisenhower, the former describing the evacuation and the Western Defense Command's reasons for it and the latter discussing his planned program. From the states, which included Utah, Arizona, Nevada, Montana, Idaho, Colorado, New Mexico, Washington, Oregon, and Wyoming, came five governors and a host of other officials, as well as a few farmers who were anxious to employ evacuees for harvesting. [9]

The governors of the mountain states were unimpressed by Bendetsen's presentation, but they adamantly opposed the "social engineering" theories on which Eisenhower's proposed program was based. They opposed any evacuee land purchase or settlement in their states and wanted guarantees that the government would forbid evacuees to buy land and that it would remove them at the end of the war. They objected to California using the interior states as a "dumping ground" for a California "problem."

People in their states were so bitter over the voluntary evacuation, they said, that unguarded evacuees would face physical danger. The most extreme viewpoint was expressed by Governor Herbert Maw of Utah who set forth a plan whereby the states would operate the relocation program with federal financing, hiring state guards and setting up camps where Japanese could be detained while working on federally approved projects. Citing strategic defense installations in Utah, he stated that evacuees should not be allowed to "roam" at large. Accusing the WRA of being too concerned about the rights and liberties of Japanese American citizens, he suggested that the Constitution be amended. The governors of Idaho and Wyoming agreed, the former advocating the round up and supervision of those who had already entered his state and the latter urging that evacuees be placed in "concentration camps." With few exceptions, the other officials present echoed these sentiments. Only Governor Ralph L. Carr of Colorado took a moderate position, and the voices of those hoping to use the evacuees for agricultural labor were drowned out. [10]

Bendetsen and Eisenhower were unable or unwilling to face down this united political opposition. The consensus of the meeting, to which these two reluctantly agreed, was that the plan for reception centers was acceptable, as long as the evacuees remained under guard within the camps. As he left Salt Lake City, Eisenhower had no doubt that private resettlement efforts had to be put off and that "the plan to move the evacuees into private employment had to be abandoned — at least temporarily." [11]

Before it had begun, Eisenhower and the WRA were thus forced by political pressure to abandon their evacuee resettlement theories and adopt an evacuee confinement policy. West coast politicians had achieved their program of exclusion, while political leaders of the interior states had achieved their program of detention. Without giving up its belief that evacuees should be brought back to normal productive life, WRA had, in effect, become their jailer, contending that confinement was for the benefit of the evacuees and that the controls on their departure were designed to prevent mistreatment by other Americans. [12]

MEMORANDUM OF AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE WAR DEPARTMENT AND THE WAR RELOCATION AUTHORITY

The tenor of Executive Order 9102 establishing the War Relocation Authority indicated that the agency would fully assume the task of formulating and implementing a relocation program. However, to expedite the removal of evacuees from the assembly centers to the relocation centers, the Army assumed certain responsibilities imposed on the WRA by the executive order. Among the most significant activities in this category were the construction and equipment of the relocation Centers and the transfer of the evacuees to the latter.

General plans for the establishment, construction, and equipment of relocation centers, then termed reception centers, were developed by the Wartime Civil Control Administration before the WRA was established. Following creation of the WRA, the WCCA halted the relocation center site selection aspects of its program. Otherwise, the WRA accepted, almost without change, the program already formulated by the WCCA during the early days of its existence. In essence, the program called for the evacuation first to assembly centers and thence to relocation centers in the interior. With the exception of site selection for the relocation centers, the WRA was free to concentrate solely on the rehabilitation aspects of the relocation program.

Close coordination was established between the headquarters of the WCCA and the WRA during the spring of 1942. Following his appointment, Eisenhower arrived in San Francisco and established his headquarters in the Whitcomb Hotel where the WCCA had already had its central administrative office. Although the headquarters of the WRA would later be established in Washington, until well into the summer of 1942 its principal office was what became known as the San Francisco Regional Office. Captain Mark H. Astrup was directed by the War Department to report for duty to Eisenhower, who in turn assigned him as Liaison Officer from the WRA to the WCCA. [13]

As discussed in Chapter Three of this study, the War Department and the WRA agreed informally to a division of labor concerning evacuation and relocation by the end of March 1942. This informal understanding was formalized in a memorandum of agreement between the two governmental entities on April 17, 1942, ten days after the aforementioned meeting at Salt Lake City. The agreement stipulated that sites for the relocation centers were to be selected by the WRA, subject to War Department approval. Such approval was necessary in the eyes of the military "in order that large numbers of evacuees might not be located immediately adjacent to present or proposed military installations or in strategically important areas." The sites, however, were to be acquired by the War Department, the WRA defraying the acquisition costs. "Initial" facilities at relocation centers would be constructed by the War Department, including "all facilities necessary to provide the minimum essentials of living, viz., shelter, hospital, mess, sanitary facilities, administration building, housing for relocation staff, post office, store houses, essential refrigeration equipment, and military police housing." War Department construction would not include "refinements such as schools, churches and other community planning adjuncts." Placement and construction of military police housing would be subject to the approval of the appropriate military commander." The War Department, through the Office of the Surgeon and the Quartermaster of the Western Defense Command, would procure and supply the initial equipment for the relocation centers such as kitchen equipment, minimum mess and barrack (beds, mattresses, and blankets) equipment, hospital equipment, medical supplies, and ten days' supply of non perishable subsistence (canned goods, smoked meats, and staples such as beans, rice, flour, sugar, etc.) based on the relocation center evacuee capacity. Once a relocation center was opened by the WRA, the War Department would transfer accountability for all such equipment to the WRA.

Other stipulations in the agreement stated that the WRA would be responsible for operating the relocation centers "from the date of opening." This responsibility would include staffing, administration, project planning, and complete operation and maintenance. The WRA would be prepared "to accept successive increments of evacuees as construction is completed and supplies and equipment are delivered." The War Department through the Western Defense Command would transport the evacuees to the relocation centers, and it had arranged for the storage of household effects of evacuees through the Federal Reserve Bank of Stan Francisco. When evacuee goods were stored and the bank delivered inventory receipts to the WRA, the agency would assume responsibility for the warehousing program. In the interest of the evacuees' security, relocation sites would be designated by the appropriate military commander or by the Secretary of War as "prohibited zones and military areas, and appropriate restrictions with respect to the rights of evacuees and others to enter, remain in, or leave such areas will be promulgated so that ingress and egress of all persons, including evacuees, will be subject to the control of the responsible Military Commander." Each relocation site would "be under Military Police patrol and protection as determined by the War Department." [14]

WAR DEPARTMENT ACTIONS TAKEN TO COMPLY WITH AGREEMENT

Subsequent to the aforementioned agreement, the War Department took steps to implement its provisions. Each assembly and relocation center within the Western Defense Command was made the basis for Civilian Restrictive Orders Nos. 1, 18, 19, 20, 23, and 24, describing the boundaries of the various camps. Center residents were required to remain within these physical boundaries. Each center resident was enjoined to obtain express written authority before undertaking to leave the designated area. During the assembly center phase, such permits were issued only by the WCCA.

On June 27, 1942, DeWitt promulgated Public Proclamation No. 8 to further assure the security of relocation centers and adjacent communities. Under its terms all center residents were required to obtain a permit before leaving the designated center boundaries. The proclamation specifically controlled ingress and egress of persons other than center residents. Violators of both the civilian restrictive orders and Public Proclamation No. 8 were subjected to the penalties provided under Public Law 503. DeWitt stated further that in "the delegation of authority to control ingress and egress," the WRA "was given full freedom of action in determining who might enter and who might leave." The military police stationed around the perimeters of the relocation centers would "not participate in this determination." Their mission, according to the general, "was merely to prevent unauthorized entry and unauthorized departure — as determined solely by the War Relocation Authority."

Four of the ten relocation centers were established outside the boundaries and jurisdiction of the Western Defense Command. To secure uniformity of control, the War Department published Public Proclamation WD:1 on August 13, 1942, designating Heart Mountain in Wyoming, Granada in Colorado, and Jerome and Rohwer in Arkansas as military areas. This proclamation contained provisions similar to those of Public Proclamation No. 8 relative to entry into and departure from relocation centers.

While DeWitt retained authority to regulate and prohibit the entry or movement of persons of Japanese ancestry in the evacuated areas (Military Areas Nos. 1 and 2), he delegated authority, on August 11, 1942, to determine entry into and departure from the relocation centers to the director of the WRA and to such persons as the director might designate in writing. The director in turn delegated responsibility to the individual directors of the relocation centers. The net result of this arrangement was that in relocation centers outside the evacuated zone, the military authorities exercised no control over ingress and egress "beyond that involved in the military police function of preventing those entries and departures not authorized by the Center Director." As to the four relocation centers located within the evacuated zone (Tule Lake, Manzanar, Colorado River, and Gila River), the control "reserved by the Commanding General [of the Western Defense Command] was limited to regulating the conditions of travel and movement through the area."

Because the WRA endeavored to use evacuee labor to construct and operate the relocation centers, further action by the military was required. The railheads serving the Colorado River, Tule Lake, Gila River, and Manzanar relocation centers were outside the center boundaries. To facilitate WRA policy, DeWitt, on September 21, 1942, authorized emergency employment of Japanese evacuees outside of the four War Relocation Authority Centers located within the evacuated areas." [15]

WAR RELOCATION CENTERS

Site Selection

Selecting the sites for the relocation centers proved to be a complicated endeavor for the WRA. Two sites — Manzanar and Poston — had been chosen by military authorities before the WRA was established. Manzanar, a site in Owens Valley, California, originally selected and acquired by the Army for a reception or assembly center, was turned over to the WRA to serve as a permanent relocation center on June 1, 1942. The Colorado River Relocation Center site at Poston, Arizona, had been acquired from the Colorado River Indian Reservation for a reception center. The WCCA never operated it, however, as Eisenhower agreed to have WRA staff operate it from the beginning. Because of difficulties in assembling a staff, Eisenhower turned over initial operations to the Indian Service. [16]

Eight more locations were needed — designed to be "areas where the evacuees might settle down to a more stable kind of life until plans could be developed for their permanent relocation in communities outside the evacuated areas." Under the terms of the agreement of April 17, 1942, the War Department and the WRA were required to agree on site locations. Each of these entities, however, had different interests. The WRA retained the portion of its early plan that called for large-scale agricultural programs in which evacuees would clear, develop, and cultivate the land. Thus, the centers were to consist of at least 7,500 acres of land and have agricultural possibilities or provide opportunities for year-round employment of other types. The WRA insisted that the centers not displace local white labor. The War Department, no longer advocating freedom of movement outside the Western Defense Command and concerned about security arrangements, insisted that sites be isolated from civilian population centers and "not be located immediately adjacent to present or proposed military installations or strategically important areas" (a term that included power lines and reservoirs). The Army also wanted each center to have an evacuee population of at least 5,000 and thus keep to a minimum the number of military police that would be needed. Considerations "of good public policy," according to the WRA, "made it desirable to locate the centers on lands either in Federal ownership or available for Federal purchase — so that improvements would not be made at Federal expense to increase the value of private property" Operational requirements dictated the selection of sites that "were within reasonable distance of a railhead and which had access to a dependable and comparatively economical supply of water and of electric power." [17]

To aid in the job of site selection, the WRA enlisted the cooperation of technicians from a number of federal and state agencies, including the Office of Indian Affairs, Soil Conservation Service, Bureau of Reclamation, Bureau of Agricultural Economics, Farm Security Administration, U.S. Forest Service, U.S. Public Health Service, and the National Resources Planning Board. More than 300 proposals were considered on paper, and nearly 100 possible sites were examined by field inspection crews. By June 5, after negotiating with many potentially affected state and local government officials and consulting with War Department personnel, the WRA completed its selection of the final eight sites. (A list of the sites, their location, and projected capacities may be seen on the next page.) [18]

Site Acquisition

Acquisition of the property for relocation center sites was a War Department function, carried out by the United States Corps of Engineers at the request of DeWitt. When military clearance was obtained, DeWitt issued a directive to the Division Engineer, South Pacific Division. who acted for the Chief of Engineers, requesting that he direct the Division Engineer concerned to proceed with the land acquisition. DeWitt notified the governor of the state in which the site was located that, because of military necessity, a relocation center was to be constructed. The cost of acquisition was paid by the WRA. [19]

Site Descriptions

The sites for the relocation centers were much alike in their isolation, rugged terrain, primitive character, and almost total lack of conveniences at the start. [20] More than any other single factor, the requirement for large tracts of land virtually guaranteed that the sites would be inhospitable. As one relocation historian has explained: "That these areas were still vacant land in 1942, land that the ever-voracious pioneers and developers had either passed by or abandoned, speaks volumes about their attractiveness." [21]

| Name | Location | Capacity (in persons) |

|---|---|---|

|

Central Utah (Topaz) Colorado River (Poston) Unit 1 Unit 2 Unit 3 Gila River (Rivers) Butte Camp Canal Camp Granada (Amache) Heart Mountain Jerome (Denson) Manzanar Minidoka (Hunt) Rohwer Tule Lake (Newell) |

West-central Utah Western Arizona Western Arizona Western Arizona Central Arizona Central Arizona Southeastern Colorado Northwestern Wyoming Southeastern Arkansas East-central California South-central Idaho Southeastern Arkansas North-central California |

10,000 10,000 5,000 5,000 10,000 5,000 8,000 12,000 10,000 10,000 10,000 10,000 16,000 |

Figure 8: U.S. Department of the Interior, War Relocation Authority, Story of Human Conservation, p. 22.

An overview of the sites for the relocation centers demonstrates their inhospitable characteristics. Manzanar and Poston, which had been selected by the Army, were in the desert and subject to high summer temperatures and dust storms. Although both would eventually produce crops, extensive irrigation would be needed. Manzanar, which was leased from the City of Los Angeles, had once been the site of ranches and orchards, but since the late 1920s the land had "reverted to desert conditions" as the city exploited its extensive acreage in Owens Valley to provide water for the expanding metropolitan area. Poston's desert climate was particularly harsh and its land was completely undeveloped and covered with brush. While some of its soil was highly suited to irrigation, much was "fourth class and so highly impregnated with salts and alkali that cultivation would be difficult." Gila River, near Phoenix, was subject to extreme summer temperatures, but was situated in a district famous for winter vegetable production. Minidoka and Heart Mountain, the two northernmost centers, were known for harsh winters and severe dust storms. Minidoka's "68,000 acres" were "covered with lava outcroppings in such a way that only about 25 per cent" of the land was "suitable for cultivation," and Heart Mountain had an annual temperature range "from a maximum of 101 degrees above zero to a minimum of 30 degrees below zero." Tule Lake, the most developed site, was located in a dry lake bed formerly controlled by the Bureau of Reclamation in a rich potato-growing section of northern California, and its fertile sandy loam soil was ready for planting. Several thousand acres of the Central Utah site "were in crop but the greatest portion was covered with greasewood brush." Granada was little better, although there was provision for irrigation as much of the site had formerly been a stock ranch. The last two sites — Jerome and Rohwer in Arkansas — were in the Mississippi River delta area and were "heavily wooded," "quite swampy," and subject to severe drainage problems, excessive humidity, and mosquito infestations. [22]

Design and Construction

By June 30, the Colorado River, Tule Lake, and Manzanar relocation centers were in partial operation with a combined evacuee population of 27,766. Four other centers — Gila River, Minidoka, Heart Mountain, and Granada — were under construction. [23]

By September 30, all the relocation centers but one — Jerome in southeast Arkansas — were in operation. Five of them were close to their population capacities, while the other four were still receiving contingents of evacuees. More than 90,000 evacuees had been transferred to the nine operating centers. [24] By November 1, the transfer of evacuees to the relocation centers was completed (see the following page for a list of the relocation centers, their dates of operation, and peak populations), and at the end of the year, the centers had the highest population they would ever have — 106,770. [25]

Design. According to the War Department's Final Report, the design of temporary buildings to house the evacuees at the relocation centers presented a problem to the Army "since no precedents for this type of housing existed." Permanent buildings were not desired. Thus, it was essential to be "as economical as possible and to avoid the excessive use of critical materials." Speed of construction was also "a vital factor because it was desired to move the Japanese out of the Assembly Centers as quickly as possible."

In the report, DeWitt observed that the Army had "available drawings of cantonment type" buildings which "might be classed as semi-permanent, and of theater of operations type buildings which were purely temporary." The latter were intended primarily for rapid construction to house troops in the rear of combat zones.

Theater of operations type buildings, according to DeWitt, "answered most of the requirements for troop shelter but were too crude for the housing of women, children and elderly persons." Normally, this type of housing had no floors; toilet facilities were meager (usually pit latrines); and heating units were omitted in all except extremely cold climates. It was decided, according to DeWitt, "that a modified theater of operations camp could be developed which would adequately house all evacuees, young and old, male and female, and still meet fairly well the desire for speed, low cost, and restricted use of critical materials." [26] Thus, despite the promise that the relocation centers would be more hospitable than the assembly centers, the type of construction chosen for the relocation centers was, according to the WRA, "similar to that in assembly centers." [27]

A set of standards and details for the construction of relocation centers was developed by the WCCA. Adopted in a conference involving DeWitt and a representative of the Office of the Chief of Engineers, they were issued on June 8, 1942, under the title — "Standards and Details, Construction of Japanese Evacuee Reception Centers." Later three supplements were issued: No. 1, dated June 18, listed the hospital equipment to be provided; No. 2, dated June 29, covered fire fighting equipment; and No. 3, dated September 23, included standards for military police housing. (Copies of these standards may be seen in Appendix C of this study.) [28]

Prior to the issuance of these standards, the WCCA experienced difficulty in establishing "uniformity" in facilities to be provided at the various relocation centers, because more than one Engineer Division was involved and each interpreted WCCA requests differently. These standards provided the necessary "uniformity" for center construction after June. The standards "provided a basis on which all of the contractors and engineers could work towards the common goal." Before the standards were issued, however, several centers, notably Manzanar, Tule Lake, Colorado River, one unit at Gila River, had been placed under construction.

Undoubtedly, experience gained during construction of those centers was reflected in the details of the standards. [29]

| Note: Resident population refers to population excluding evacuees on short-term and seasonal leave. | ||||||||

| CENTER | L O C A T I O N | DATE FIRST EVACUEE ARRIVED |

PEAK POPULATION | DAYS CENTER IN OPERATION |

DATE LAST RESIDENT DEPARTED | |||

| State | County | Last Post Office Address |

Date | Population | ||||

| Central Utah Colorado River Gila River Granada Heart Mountain Jerome Manzanar Minidoka Rohwer Tule Lake |

Utah Arizona Arizona Colorado Wyoming Arkansas California Idaho Arizona California |

Millard Yuma Pinal Prowers Park Drew & Chicot Inyo Jerome Dasha Modoc |

Topaz Poston Rivers Amache Heart Mountain Denson Manzanar Hunt Relocation Newell |

9-11-42 5-8-42 7-20-42 8-27-42 8-12-42 10-6-42 1/6-1-42 8-10-42 9-18-42 5-27-42 |

3-17-43 9-4-42 12-30-42 2-1-43 1-1-43 2-11-43 9-22-42 3-1-43 3-11-43 12-25-44 |

8,130 17,814 13,348 7,318 10,767 8,497 10,046 9,397 8,475 18,789 |

1,147 1,301 1,210 1,146 1,187 634 1,270 1,176 1,170 1,394 |

10-31-45 11-28-45 11-10-45 10-15-45 11-10-45 6-30-44 11-21-45 10-28-45 11-30-45 3-20-46 |

Figure 9: U.S. Department of the Interior, War Relocation Authority, Evacuated People, p. 17.

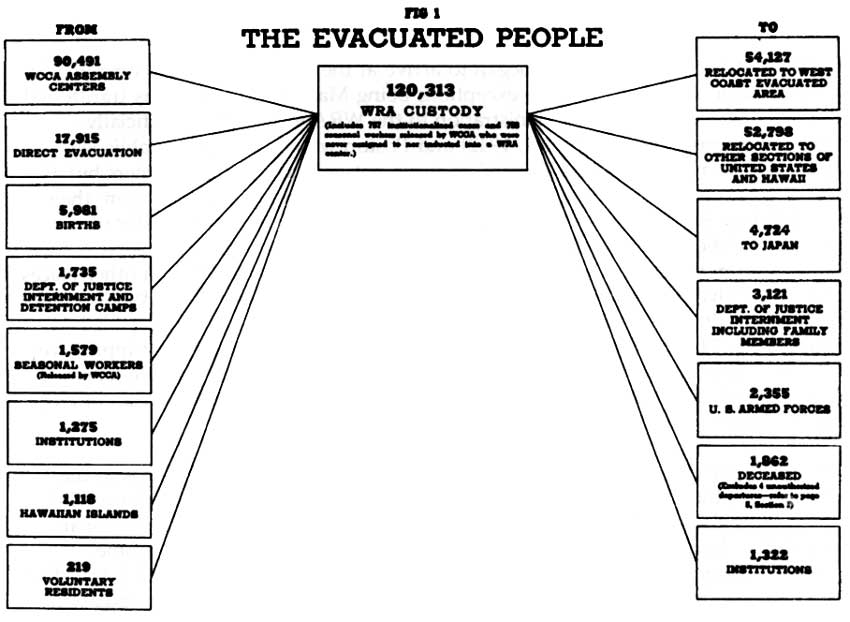

Typical Center Lay-Out. In the War Department's Final Report, DeWitt provided details and drawings for a typical relocation center designed for a resident evacuee population of 10,000. The buildings in each center, according to DeWitt, were "grouped as to use." The evacuee housing group was the largest and consisted of the blocks in which the evacuees had their homes. Several blocks in this group were reserved "for future schools, churches, and recreational centers." The other principal groups in each center included administration and warehouse groups, a military police camp, and a hospital. (A copy of a "Typical Plot Plan, War Relocation Center, 10,000 Population" may be seen on the following pages.) [30]

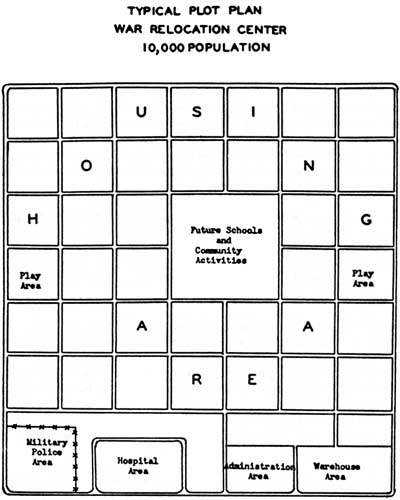

The typical evacuee housing area, or camp, was an approximate square-mile barbed wire enclosure. There were 36 housing blocks. Each block contained 12 barrack buildings (20 feet x 120 feet), a recreation building, a mess hall (40 feet x 120 feet), and a combination H-shaped structure that had toilet and bath facilities for both men and women as well as a laundry room and a heater room. (A copy of a "Typical Housing Block, War Relocation Center" may be seen on the following pages.) [31]

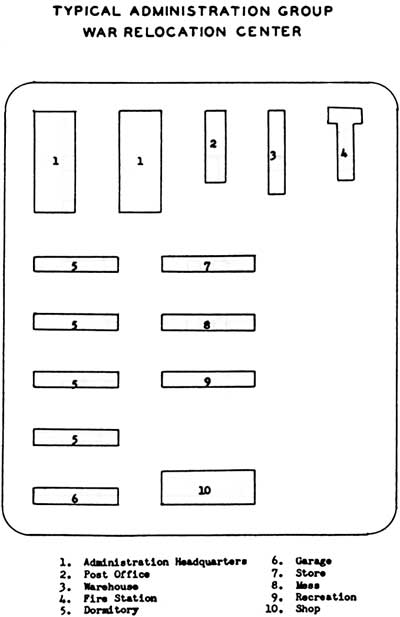

The administration building group comprised the structures devoted to the use of relocation center management. Included in a typical administrative group were four dormitories for non-evacuee employees, two office buildings, a post office, store, fire house, warehouse, shop building, garage, mess hall for the non-evacuee staff, and a recreation building. (A copy of a "Typical Administration Group, War Relocation Center" may be seen on the following pages.) [32]

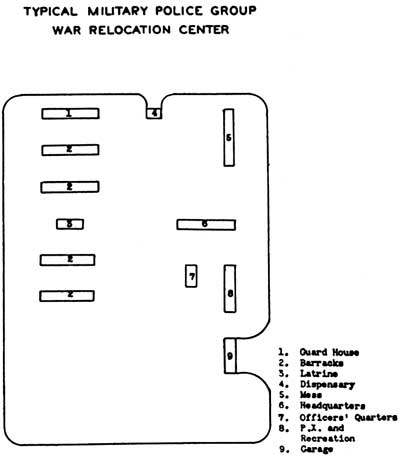

The military police camp was usually separated from the relocation center proper, thus aiding in the prevention of "fraternization between the guards and the evacuees." The military police buildings on most centers were of the "modified mobilization type," and in a few cases the buildings were of prefabricated construction. [33] The buildings in the group, which provided facilities for one company of military police, included four enlisted men s barracks, a bachelor officers' quarters, headquarters and supply building, guard house, recreation and post exchange building, a dispensary, latrine, and bathhouse, mess hall, and garage. (A copy of a "Typical Military Police Group, War Relocation Center" may be seen on the following pages.) [34]

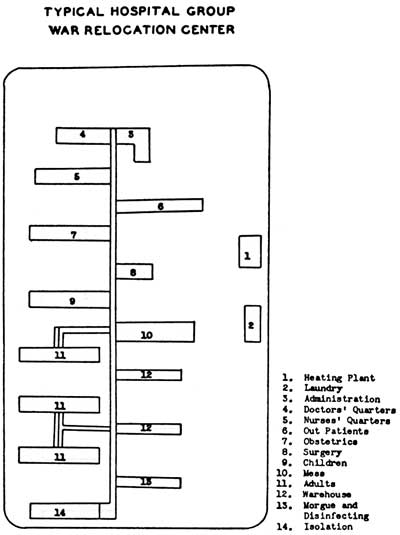

The hospital building group provided "space for the principal medical activities carried on in any metropolitan community." The hospital buildings included an administration building, doctors' quarters, nurses' quarters, three general wards for adults, an outpatient building, obstetrical ward, surgery building, pediatric ward, mess hall isolation ward, morgue, laundry, two storehouses for supplies and equipment, and a boiler house that supplied steam for heating buildings and operating sterilization equipment. (A copy of a "Typical Hospital Group, War Relocation Center" may be seen on the following page.) [35]

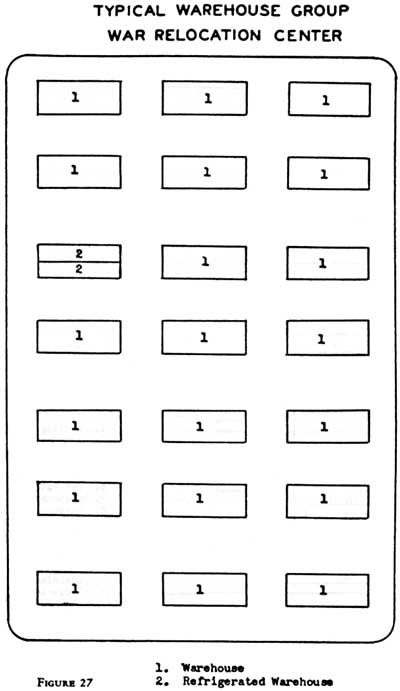

The warehouse group provided storage space for large quantities of food, supplies, and equipment. Some were refrigerated for the preservation of perishable foods, and the balance for storing staple foods, supplies, and equipment. Originally, two 20-foot x 100-foot refrigerated warehouses were provided for a 10,000-person capacity relocation center, but it was found to be more efficient to erect one 40-foot x 100-foot building, divided into compartments for different types of food, such as fruits and vegetables, meats, and dairy products. The standard relocation center of 10,000 evacuees had twenty 40-foot x 100-foot warehouses which were not partitioned or heated for dry storage. (A copy of "Typical Warehouse Group, War Relocation Center" may be seen on page 110.) [36]

|

| Figure 10: Typical Plot Plan, War Relocation Center U.S. War Department, Final Report, p. 266. |

|

| Figure 11: Typical Housing Block, War Relocation Center, U.S. War Department, Final Report, p. 267. |

|

| Figure 12: Typical Administration Group, War Relocation Center, U.S. War Department, Final Report, p. 268. |

|

| Figure 13: Typical Military Police Group, War Relocation Center, U.S. War Department, Final Report, p. 269. |

|

| Figure 14: Typical Hospital Group, War Relocation Center, U.S. War Department, Final Report, p. 270. |

|

| Figure 15: Typical Warehouse Group, War Relocation Center, U.S. War Department, Final Report, p. 271. |

Construction of the relocation centers included provision for water supply, sewage disposal, electric power and lighting, and telephone facilities. DeWitt described the guidelines and features for installation of each of these systems:

Water supply systems, designed to provide 100 gallons per capita per day with ample storage capacity, were constructed to provide adequate water for culinary, sanitary, and fire-protection purposes. In most instances, the water was secured from wells which produced potable water that needed no treatment, but in some centers partial or complete treatment was necessary.

Water-borne sewage disposal conforming to minimum health requirements of the respective state health departments was provided. Sewer capacity was based on 75 gallons per capita per day The sewage systems ranged from large septic tanks with no chlorination of effluent to modern disposal plants that included digesters, chlorinators, sludge beds, and effluent ponds.

Electric power and lighting was designed on the basis of 2,000 KVA per 10,000 population. Street lighting was installed in the earlier centers, but after the standards were issued one light at each end of all main buildings constituted outdoor lighting.

Telephone facilities at relocation centers generally consisted of not more than four trunk lines to a 40-line board with 60 handset stations for administration and operation and 15 handsets for the military police unit. One separate outside line with handset station was provided for the commanding officer of the military police unit. The installation of the telephone systems was conducted or supervised by the Signal Corps of each Service Command in its area. [37]

Construction. Plans and specifications for the construction of the buildings at the relocation centers were prepared at the District Engineer's office in the district in which the centers were located. These plans were submitted for approval to the Civil Affairs Division, General Staff (thence to WCCA) of the Western Defense Command. After approval, contracts were awarded by the district engineers to private construction firms.

During construction of the relocation centers, considerable difficulty was encountered in obtaining building materials and mechanical equipment as well as skilled building-trades craftsmen because of the war emergency. Deliveries were slow, and it was necessary to have "expediters working constantly to speed shipments." Spot shortages of various types of lumber occurred frequently, and nails, pipe, plumbing fixtures, and pumps for water supply and sewage systems were particularly difficult to secure on schedule. Skilled building-trades craftsmen were scarce in some localities, particularly the most isolated locations, and in some cases workers had to be transported long distances. To keep them on the job it was sometimes necessary for contractors to establish commissaries and dormitories near the relocation center sites.

The War Department prepared a preliminary estimate of the cost of building the ten relocation centers on December 1, 1942. The total estimated cost was $56,482,000 or approximately $471 per evacuee. According to the estimates, the most expensive center to be built was at Colorado River ($9,365,000), while the least expensive was Manzanar ($3,764,000). The center having the highest per capita cost was Minidoka ($584), and the lowest was Manzanar ($376). [38]

According to the WRA, "practically all construction and improvement work over and above this subsistence base [as constructed by the Corps of Engineers] was carried out by the evacuees themselves after their arrival at the center." The plan "followed was to bring into each center first a small contingent [about 200] of evacuee specialists — such as cooks, stewards, doctors, and nurses — in order to prepare for the mass arrivals later." As the center began to fill up and the people had a chance to become settled, "improvements on individual family quarters and on the community as a whole were undertaken." [39]

Description of Buildings. The War Department's Final Report provides general standard descriptions of the buildings constructed at relocation centers. The descriptions of these hastily constructed buildings demonstrate the military precision that went into their planning and design and provide ample evidence of their spartan and austere nature.

Originally, barracks or living quarters were 20-foot x 100-foot structures divided into five 20-foot x 20-foot rooms that were termed "apartments" by the Army. To accommodate differences in family sizes the design was changed to provide for 120 foot-long structures with two 16-foot x 20-foot, two 20-foot x 20-foot, and two 24-foot x 20-foot apartments. Ideally, one family was assigned to an apartment, but this goal was not always attained. No toilet or bath facilities were provided in the barracks, because they were located in a common building for each block. A heating unit, either of the cannon type stove or cabinet oil heater variety, depending on the fuel used, was placed in each apartment. In the colder climates wall board was provided to the WRA so that the evacuees could line and seal the interiors of their quarters. The exterior walls and roofs were generally of shiplap or other sheathing covered with tarpaper. One drop light per room was furnished. Floors of the apartments at all centers were wood, except at Granada, where they were built of brick. Single floors were found unsatisfactory because of the cracks which resulted when the green lumber used for construction dried. At several centers, including Manzanar, Tule Lake, Gila River, and Colorado River, the WRA later installed "a patented flooring called Mastipave which gave a smooth, washable surface." Fly screening was provided to the evacuees to make screens for their quarters.

In the first relocation centers to be constructed, such as Manzanar, bachelors were housed in barracks which were not partitioned into rooms. Usually there were two of these buildings to a block, but it was proven to be more efficient to divide all barracks into rooms. Bachelors could then be assigned wherever desired and all buildings were available for the housing of families.

Mess halls were generally 40-foot x 100-foot structures. Approximately one-third of the mess halls' square footage was devoted to kitchen, store room, and space for washing dishes, pots and pans, and kitchen utensils. Windows and doors were screened against flies, and heat was provided by cannon stoves or cabinet heaters. Tables, with benches, to seat 300 persons were standard. Each kitchen was to be equipped with three ranges, 60 cubic feet of electric refrigeration, scullery sinks, hot water heater and tank, cooks' tables, and a meat block. Shelving was built into the store room, and serving counters were provided. Concrete floors were standard after the first four camps, including Manzanar, were constructed with wooden ones.

One recreation building was constructed for each evacuee housing block. This 20-foot x 100-foot structure had no partitions or equipment with the exception of heaters.

A combination latrine and laundry building, constructed in a "H" shape, was located between the two rows of barracks in each block. One side of the structure contained the block laundry, and the other the men's toilet and shower rooms and the women's toilet and bath rooms. A water heater and storage tank were housed in the space forming the cross bar of the "H". The floors of this building were concrete.

The laundry room was fitted out with 18 double compartment laundry trays and 18 ironing boards with an electric outlet at each board. Plumbing fixtures in each unit or block facility were hung on the basis of eight showerheads, four bathtubs, fourteen lavatories, fourteen toilets, and one slop sink for the women; and twelve showerheads, twelve lavatories, ten toilets, four urinals, and one slop sink for men. [40]

TRANSFER OF SUPPLIES FROM ASSEMBLY TO RELOCATION CENTERS

Necessary supplies, equipment, and subsistence items for the relocation centers was the responsibility of the Quartermaster, Western Defense Command and Fourth Army. Some supplies and equipment used at assembly centers, including cots, mattresses, blankets, kitchen equipment, and eating utensils, were transferred to the relocation centers, while additional supplies were shipped from Quartermaster Depots. Each relocation center was provided with an initial supply of ten days' requirements of non-perishable foods, including canned goods, smoked meats, and staples such as beans, rice, flour, and sugar. According to the War Department's Final Report, the logistics of transferring evacuees from assembly to relocation centers were developed by the WCCA "in such a manner as to result in the use of a minimum of supplies and equipment." By providing the relocation centers that "received the first movements of evacuees with sufficient supplies and equipment to handle transfers for a three or four week period, and by scheduling the movement of supplies and equipment out of evacuated assembly centers to relocation centers in the order in which evacuees would be transferred to them," it was possible, according to General DeWitt, "to utilize again the supplies and equipment originally purchased for the Japanese in Assembly Centers." Transfer movements of evacuees were timed to provide a two-week period during which cots, blankets, mattresses, cooking and eating utensils, and other supplies and equipment to be moved from assembly to relocation centers could be inventoried, "renovated," and shipped to the new centers. [41]

TRANSFER OF EVACUEES FROM ASSEMBLY CENTERS TO RELOCATION CENTERS

According to the War Department's Final Report, evacuees were transferred from the assembly centers and custody of the military to the WRA under the provisions of the aforementioned April 17, 1942, agreement "as rapidly as Relocation Centers were completed for beneficial occupancy." Thus, evacuees passed from the custody of the Army to the WRA in the following ways during 1942:

Regular transfer movement from an assembly to a relocation center

Direct transfer of the Manzanar Reception Center on June 1, 1942

Direct evacuation from an exclusion area to the relocation centers at Colorado River, Gila River, and Tule Lake

Release to WRA on work furlough

Transfer of individual evacuees and special groups to WRA centers

Transfer to WRA during September and October the responsibilities for institutional cases remaining in hospitals, homes, prisons, jails, etc., physically located within the evacuated area

The total number of evacuees transferred by the WCCA to the WRA by these methods was 111,155. (A copy of a summary chart may be seen on the following page.) These transfers accounted for all the persons who came directly under the evacuation program with three principal exceptions. The exceptions included: (1) those persons who had been released from assembly centers in accordance with regulations governing the release of mixed-marriage cases; (2) a few persons who were deferred from evacuation and later release; and (3) some persons who were permitted to leave the assembly centers for interior points to join their families who had previously established residence outside the evacuated area.

TABLE 32.—SUMMARY OF TRANSFER OF EVACUEES FROM CUSTODY OF THE ARMY TO CUSTODY OF WAR RELOCATION AUTHORITY

| Place of Custody | Total | Transfer order |

Direct evacuation | Other movement |

| WRA Custody To all Relocation Centers Central Utah Colorado River Hear Mountain Jerome (1) Gila River Granada Manzanar (2) Minidoka Rohwer Tule Lake To other than Relocation Centers Furlough Institutions, etc. | ||||

| 111,155* 108,503 8,255 17,740 10,972 7,674 13,234 7,567 10,049 9,484 8,232 15,296 2,652* 1,630 1,022* |

89,698 89,698 8,223 5,919 10,954 7,674 10,202 7,554 9,731 9,467 8,232 11,742 ...... ...... ...... |

18,249 18,026 ...... 11,711 ...... ...... 2,946 ...... 165 ...... ...... 3,204 223 223 ...... |

2,414 779 32 110 18 ...... 86 13 153 17 ...... 350 1,635 1,407 228 |

|

* Including 794 persons remaining in institutions in evacuated

area, and who were never evacuated. (1) Including 894 persons enroute from Fresno on October 31. (2) 9,666 evacuees transferred by inter-agency agreement, June 1, 1942. |

Figure 16: Table 32.—Summary of Transfers of Evacuees From Custody of Custody of the Army to War Relocation Authority U.S. War Department, Final Report, p. 279.

In accord with the provisions of the agreement between the War Department and the WRA, DeWitt authorized the Assistant Chief of Staff for Civil Affairs to make the necessary arrangements for the transfer of evacuees from assembly to relocation centers on May 23, 1942. His directive also granted authority to call on the sector commanders for necessary military assistance to facilitate the transfer.

A "schedule of movement" was prepared by the military as the first step in the plan for evacuee transfers. The following factors, although not always realized, were presumably considered in formulating this schedule:

Date when each relocation center would be available for "beneficial occupancy," including progress of construction and availability and transfer of supplies

Urgency of early evacuation of assembly centers "having pit latrines or which presented an abnormal fire hazard"

Desirability "for efficient operation, of transferring the evacuees in an entire Assembly Center in a continuous movement, and, if possible, to the same Relocation Center destination"

Need to balance the urban and rural populations in each relocation center, and the desirability of relocating together the rural and urban groups which had been evacuated from the same general area

Attainment of a minimum climatic change consistent with the placement in available centers

Transfer of evacuees to a relocation center as close to their community of former residence as possible

Availability of sufficient train equipment to transport the evacuees without interrupting the prearranged schedules of major troop movements

A preliminary "schedule of movement" was drafted in early June. In addition to the proposed transfers from assembly to relocation centers, it allowed for the direct evacuation of Japanese from the California portion of Military Area No. 2 to relocation centers. Because of the delay in construction of some relocation centers and the unavailability of some types of supplies and equipment, however, this preliminary schedule was revised in August. The initial schedule had called for the evacuation of all assembly centers by October 12, while the revised schedule set October 30 — "the realized goal" — as the date of the final movement. (The logistics of transfer prescribed by the WCCA is represented in the chart on the following page.)

|

|

Figure 17: Transfers from Assembly to Relocation Centers, U.S. War

Department, Final Report, p. 281. (click on the above image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Specific transfer orders, a list of which may be seen in Appendix D, were issued covering all of the regular transfer movements of evacuees from assembly to relocation centers. The transfer orders were prepared by the Civil Affairs Division, General Staff, issued by Headquarters, Western Defense Command, and addressed to the Commanding General of the Sector in which the movement originated as well as to all WCCA agencies concerned with transfer operations. Transfer orders Nos. 1-5 and 7, however, were issued directly by the WCCA director. Such orders were usually issued 12 to 19 days prior to the departure of the first train of evacuees to be moved under the order.

Each transfer order directed the agencies concerned to make the necessary arrangements for the transfer of the evacuees. The orders contained information on the approximate number of persons, the assembly center of origin, the relocation center destination, the dates of movement, and, where necessary, a specific description by family numbers or civilian exclusion order of the exact group of evacuees who were to be moved. It also directed that a suitable military escort be provided and that the necessary transportation and meals be furnished to the evacuees, Caucasian medical attendants, and military escort. A formal operating procedure developed to prepare the orders was formalized in a "Procedure Memorandum" issued on June 26, 1942 (a copy of which is printed in the Final Report, pp. 592-99)

As much as possible, the evacuation of an assembly center was accomplished by blocks or other administrative areas within the center, thus permitting the closing off of unused portions of the center for cleanup by the remaining evacuees and for the removal, inventory, and storage of government property. A cleanup crew of evacuees was retained for a short period after the main body of evacuees had been transferred to a relocation center. These workers performed services necessary to prepare the center for reoccupancy and assisted the center staff in the completion of fiscal and property records and the storage of government property As each assembly center was evacuated, residents of the evacuated area were required to perform necessary policing of the barracks, latrines, and grounds immediately surrounding the barracks. All shelving, wiring, and other facilities installed by evacuees in their living quarters were removed.

Once evacuation of an assembly center started, it was generally continued until the center was empty. Evacuees were normally moved by special train in increments of approximately 500 persons, because the military considered that number to be an optimum train load. It was also the maximum number that could be efficiently handled in departing an assembly center and quickly processed on arrival at a relocation center. Movements occurred daily or on alternate days until the ordered transfer was competed. Of the evacuees transferred, only 710 were moved by bus — for relatively short distances. All other transfers were conducted with the use of 171 special trains.

Coordination for transportation necessary to move the evacuees, baggage, and freight was the responsibility of the Rail Transportation Officer in the Western Defense Command's Office of the Quartermaster. The U.S. Public Health Service provided medical personnel to accompany the evacuees to the relocation centers, providing one doctor and one or two registered nurses to accompany the longer transfers. The Sector Commander furnished the necessary military personnel, including a sector transportation officer, a train commander, and sufficient military personnel "to assure the safe conduct of the evacuees." The train commanders took responsibility for the evacuees at the exit gate of the assembly center. The evacuees were permitted "to take on the same train only such personal effects and bedding as required by the evacuee immediately upon arrival at the War Relocation Center." Two baggage cars were to be provided for each train. Excess baggage was to be sent to the relocation center by freight. When two or more meals were required enroute, dining cars were included in the train equipment. For movements involving only one or two meals, lunches were provided by the assembly center management. [42]

EVACUEES' EXPERIENCES DURING TRANSFER TO RELOCATION CENTERS

Notwithstanding the Army's planning efforts for the transfer of evacuees from the assembly to the relocation centers, the evacuees often experienced less than ideal conditions. In its Second Quarterly Report, the WRA reported that during the summer and early fall of 1942 "contingent after contingent of evacuees boarded trains at the assembly centers and travelled hundreds of miles farther inland to the partially completed relocation centers." In addition some 8,000 to 9,000 people of Japanese ancestry were moved from their homes in the eastern half of California (Military Area No. 2 portion of the state) directly into relocation centers beginning on July 9. The WRA observed that in "planning the movement to relocation centers, every effort was made to hold families intact and to bring together people who came originally from a common locality." However, the agency noted:

Evacuees from the San Francisco Bay Area, for example, were first moved to the Tanforan and Santa Anita Assembly Centers and later reunited at the Central Utah Relocation Center. Colorado River Relocation Center drew its population largely from the Imperial Valley, from the Salinas and Pinedale Assembly Centers, and Military Area No. 2. The two northern-most relocation centers — Minidoka in Idaho and Heart Mountain in Wyoming — received their contingents mainly from the assembly centers at Puyallup, Washington and at North Portland, Oregon. Gila River absorbed the whole population of the assembly centers at Tulare and Turlock, plus several contingents from Santa Anita and others from Military No. 2.

"Despite this general pattern," however, the WRA reported that "some mingling of heterogeneous populations was inevitable." Evacuees at the Santa Anita Assembly Center, for example, "were widely dispersed in the movement to relocation centers." "These people, most of whom were originally from Los Angeles, were scattered among the Gila River, Granada, Central Utah, and Rohwer Relocation Centers." Later, some Santa Anita evacuees would also be sent to Manzanar and Jerome. At Granada, "where the highly urban Santa Anita people were combined with predominantly rural contingents from the Merced Assembly Center," the WRA noted that "some minor tensions had already developed between the two groups before" the end of September. "Sincere efforts were being made on both sides, however, to create a better mutual understanding and to develop greater community solidarity." [43]

The train trips, particularly the longer ones, were often uncomfortable for the evacuees. Even on trips of several days, sleeping berths were provided only for infants, invalids, and others who were physically incapacitated. Most evacuees sat up during the entire trip, and mothers with small children who were allowed berths were separated from their husbands. Ventilation was poor because the military had ordered that the shades be drawn for security purposes. The toilets sometimes flooded, soaking suitcases and belongings on the floor. The trips were slow because the trains were old, and sometimes they were shunted to sidings while higher-priority trains passed. Delays could be as long as ten hours. Arrangements for meals were sometimes less than satisfactory, and medical care was frequently poor. Although the WCCA had ordered that trains be stopped and ailing evacuees hospitalized along the route, at least two infants died during the journeys. [44]

Some evacuees were harassed by the military guards. One evacuee later recalled:

When we finally reached our destination, four of us men were ordered by the military personnel carrying guns to follow them. We were directed to unload the pile of evacuees' belongings from the boxcars to the semi-trailer truck to be transported to the concentration camp. During the interim, after filling one trailer truck and waiting for the next to arrive, we were hot and sweaty and sitting, trying to conserve our energy, when one of the military guards standing with his gun, suggested that one of us should get a drink of water at the nearby water faucet and try and make a run for it so he could get some target practice. [45]

Another evacuee remembered:

At Parker, Arizona, we were transferred to buses. With baggage and carryalls hanging from my arm, I was contemplating what I could leave behind, since my husband was not allowed to come to my aid. A soldier said, "Let me help you, put your arm out." He proceeded to pile everything on my arm. And to my horror, he placed my two-month-old baby on top of the stack. He then pushed me with the butt of the gun and told me to get off the train, knowing when I stepped off the train my baby would fall to the ground. I refused. But he kept prodding and ordering me to move. I will always be thankful [that] a lieutenant checking the cars came upon us. He took the baby down, gave her to me, and then ordered the soldier to carry all our belongings to the bus and see that I was seated and then report back to him. [46]

At the end of the lengthy train trips were the new relocation centers. To travel-weary refugees, the spectacle of guard towers and armed sentries in the middle of vast, primitive expanses of nothingness came as a rude shock, especially since they had been assured that the relocation centers were to be residential communities without the most repressive aspects of the hastily-constructed assembly centers. [47] Upon arrival at the relocation centers the evacuees underwent an often grueling "intake" procedure, which usually took about two hours. The process included five principal steps: (1) a medical check; (2) issuance of registration and address forms to each family group; (3) assignment to quarters; (4) emergency recruitment of evacuees needed in the mess halls and other essential community services; and (5) delivery of hand baggage to individual families. [48]

In his The Governing of Men, Alexander H. Leighton described the "intake" process and its effect on the evacuees at the Poston relocation center. He observed:

In May the physical shell of Poston began to fill with its human occupants. First came the volunteers and then a swelling stream of evacuees until the city of barracks had become alive. . . .

[The] first volunteers were soon followed by others until a total of 251 turned to work in the growing heat and cleaned up the barracks for the 7,450 evacuees who arrived during the succeeding three weeks. The volunteers worked at the receiving stations interviewing, registering, housing and explaining to the travel-weary newcomers what they must do and where they must go. . . .

The new arrivals, coming in a steady stream, were poured into empty blocks one after another, as into a series of bottles. The reception procedure became known as "intake" and it left a lasting impression on all who witnessed or took part in it.When the bus stops, its forty occupants quietly peer out to see what Poston is like. A friend is recognized and hands wave. The bus is large and comfortable, but the people look tired and wilted, with perspiration running off their noses. They have been on the train for twenty-four hours and have been hot since they crossed the Sierras, with long Waits at desert stations. . . .

They begin to file out of the bus, clutching tightly to children and bundles. Military Police escorts anxiously help and guides direct them in English and Japanese. They are sent into the mess halls where girls hand them ice water, salt tablets and wet towels. In the back are cots where those who faint can be stretched out, and the cots are usually occupied. At long tables sit interviewers suggesting enlistment in the War Relocation Works Corps. . . . Men and women, still sweating, holding on to children and bundles, try to think. A whirlwind comes and throws clouds of dust into the mess hail, into the water and into the faces of the people while papers fly in all directions. . . .

Interviewers ask some questions about former occupations so that cooks and other types of workers much needed in the camp can be quickly secured. Finally, fingerprints are made and the evacuees troop out across an open space and into another hall for housing allotment, registration and a cursory physical examination . . . In the end, the evacuees are loaded onto trucks along with their hand baggage and driven to their new quarters; there each group who will live together is left to survey a room 20 by 25 feet with bare boards, knotholes through the floor and into the next apartment, heaps of dust, and for each person an army cot, a blanket and a sack which can be filled with straw to make a mattress. There is nothing else. No shelves, closets, chairs, tables or screens. In this space 5 to 7 people, and in a few cases 8, men, women and their children, are to live indefinitely.

"Intake" was a focus of interest and solicitude on the part of the administrative staff. The Project Director said it was one of the things he would remember longest out of the whole experience at Poston, He thought the people looked lost, not knowing what to do or what to think. [49]

While the intake process was an inauspicious introduction to the WRA for the evacuees, the physical condition of the relocation centers at the time of arrival also contributed to their feelings of disaffection. At the end of September the WRA reported on living conditions in the centers:

Seriously hampered by wartime shortages of materials and wartime transportation problems, construction of the relocation communities went busily forward under supervision of the Army Corps of Engineers throughout the summer months, At most centers, the building of evacuee barracks was finished on or very close to schedule, Installation of utilities, however, involved more critical materials and consequently moved forward at a considerably slower rate. At some of the centers, evacuees were forced temporarily to live in barracks without lights, laundry facilities, or adequate toilets. Mess halls planned to accommodate about 300 people had to handle twice and three times that number for short periods as evacuees poured in from assembly centers on schedule and shipment of stoves and kitchen facilities lagged behind. In a few cases, where cots were not delivered on time, some newly arriving evacuees spent their first night in relocation centers sleeping on barracks floors. At nearly all centers, evacuee living standards temporarily were forced, largely by inevitable wartime conditions, far below the level originally contemplated by the War Relocation Authority.

The WRA went on to report that "most of these difficulties were either straightened out or well on the way to solution" by the end of September. Still ahead, however, was "the sizable job of constructing buildings which were not included in the agreement with the War Department" such as schools and administrative housing. "With the fall term already started at most public schools in the United States, evacuee children were getting ready to resume their education in barracks and other buildings which were never intended for classroom use." [50]

Other developments also contributed to the confusion and disgust of many evacuees as they entered the relocation centers, One of the most disconcerting issues confronting both the WRA and its new charges was the agency's unreadiness to undertake its mandate. Having selected the sites for the relocation centers, the WRA quickly turned to its second job — development of policies and procedures that would control the lives of the evacuees — while the centers were being constructed. In his letter to Eisenhower on April 6, Masaoka set forth a long list of recommendations for regulating life in the camps and stressed, among other things, the importance of respecting the citizenship of the Nisei, protecting the health of elderly Issei, providing educational opportunities, and recognizing that the evacuees were "American" in their outlook and wanted to make a contribution to the war effort. [51]

Although the WRA agreed with many of these recommendations, it was slow in developing policies for operating the relocation centers. The WRA would later describe the difficulties it encountered as it grappled with the issue of policy formulation:

Ideally the War Relocation Authority should have had a complete set of operating policies drawn up and ready to go into effect when the first contingent of 54 evacuees arrived at the gates of the Colorado River Relocation Center on May 8, 1942. Actually it was 3 weeks after this date before the agency produced a set of policies which were then frankly labeled by the Director as 'tentative, still fairly crude, and subject to immediate change.' And it was not until August, when more than half of the evacuee population had been transferred to WRA supervision, that the Authority was able to provide the centers with carefully conceived and really dependable answers to some of the more basic questions of community management.

The chief reason for the delay in producing a reliable set of basic policies lies in the fact that WRA had to start virtually from scratch, . . . no agency — governmental or private — had ever been called upon before to care for the needs of a tenth of a million men, women, and children who had been uprooted from their homes under a cloud of widespread popular distrust in time of total war. The problem of managing camps under these conditions were so unprecedented, so complex, and so unpredictable that the process of policy formulation continued, at varying levels of intensity, throughout the major part of the agency's active life. Nevertheless, the principal outlines of center management policy were laid down in 1942 — in tentative form in a statement issued at the Washington office on May 29 and then, somewhat more thoughtfully and against a brief background of actual operating experience, in an agency conference held at San Francisco in the middle of August. [52]

Given the limited time available and the novelty of WRA's task as both jailer and advocate for the evacuees, it is not surprising that the agency was not fully prepared for the evacuees when they began arriving at the relocation centers, Furthermore, the "Tentative Policy Statement" issued in mimeographed form on May 29 must have left the evacuees puzzled and confused. Committed to a policy of detention even before the relocation centers were completed, the WRA announced that it had begun making plans to assure evacuees "for the duration of the war and as nearly as wartime exigencies permit, an equitable substitute for the life, work, and homes given up, and to facilitate participation in the productive life of America both during and after the war." [53] Nevertheless, the fact that WRA was unable to provide dependable answers to basic questions, such as policies on evacuee employment and compensation, self-government, internal security, education, agricultural production, and consumer enterprises in the relocation centers, until late August and early September contributed to the disaffection and anxiety that increasingly characterized evacuee reactions to the relocation centers. [54]

The confluence of diverse political interests had again conspired against the evacuees. The condition of the relocation centers at which the evacuees arrived in 1942 were barely an improvement over the hastily constructed and makeshift assembly centers they had left. The increased freedom and possible resettlement they had anticipated had been reversed in favor of confinement, and the rules and policies that would govern their uprooted lives for the indefinite future were uncertain, tentative, or non-existent, The Manzanar War Relocation Center, located in the arid expanse of Owens Valley in eastern California, will provide a poignant case history of the WRA administered program to both detain and relocate persons of Japanese ancestry during World War II.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

manz/hrs/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2002