|

MANZANAR

Historic Resource Study/Special History Study |

|

CHAPTER SIX:

SITE SELECTION FOR MANZANAR WAR RELOCATION CENTER — HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF OWENS VALLEY AND MANZANAR VICINITY

In March 1942, a site in Owens Valley, approximately five miles south of Independence, California, was selected by the U. S. Army for establishment of a reception or assembly center for persons of Japanese descent who were to be evacuated from the west coast. Located on lands that had been settled by a fruit-growing community known as Manzanar during the early 20th century, this site would become known as the Manzanar War Relocation Center. Although this site's historical significance is based primarily on the events that occurred here during World War II, the historical development of the Manzanar vicinity and Owens Valley provide insights into the settlement and growth of a little-known chapter in eastern California history.

SITE SELECTION

Two principal sources provide explanations for the military's decision to locate a reception or relocation center in the Owens Valley in March 1942. The first is the Project Director's Report, prepared in February 1946 by two men who would play influential roles in the development and operation of Manzanar. The two men were Robert L. Brown, who became reports officer at Manzanar on March 15, 1942, and later served as assistant project director at the relocation center from January 1943 to February 1946, and Ralph P Merritt, who served as project director at Manzanar from November 24, 1942, until the center closed on November 21, 1945. [1] The second source is a report written in early April 1942 by Milton E. Silverman, a feature writer for the San Francisco Chronicle, who was given a 60-day assignment by the Western Defense Command to investigate the relocation center operations of the Wartime Civil Control Commission. [2] Although the two reports offer some conflicting viewpoints on the events surrounding the Manzanar site selection, they corroborate each other in the essential details of the decision.

The Brown and Merritt report noted that the Manzanar site was located in Inyo County in the Owens River Valley, approximately 230 miles north of Los Angeles. A "long, narrow, semi-arid valley bounded on the west by the towering Sierra Nevada mountains and on the east by the colorful, but not quite-so-high Inyo mountains," Owens Valley had "a colorful history having been the scene of one of the great 'water-wars' of the West."

In the early years of the 20th century, the City of Los Angeles "in its quest for water turned to the steams flowing down the eastern slopes of the Sierra" in Owens Valley and "conceived and built a 230 mile aqueduct to carry these waters to its rapidly expanding boundaries." During the next two decades, Los Angeles, through its Department of Water and Power (LADWP), purchased "most of the land in the Owens Valley to protect this source of water [i.e., the water rights], and, as a consequence. forced most of the land to revert back to semi-arid desert land." "A few cattle and sheep men were given grazing leases, the farmers moved away, and the towns shrank to semi-ghost towns."

In the 1930s, "with the advent of better roads and increased population in Southern California," however, Owens Valley "began to be visited by vacationists looking for recreation spots during the summer months)." This "early trickle" of tourists "kept the towns from complete annihilation, and pumped new hope into the veins of the merchants who had refused to leave." "New leadership," according to Brown and Merritt, "began to focus the spotlight of national publicity on the injustices perpetrated by the City of Los Angeles." During the late 1930s, a "great wave of interest in Inyo and the Valley swept California" as tourists "flocked to the high mountains, the towns prospered, Los Angeles sold back some of the town property, and leased some ranches for farming." Owens Valley was again in the public eye and on the 'uphill' grade."

One of the supporters of the "new development" of Owens Valley was Manchester Boddy, influential publisher of the Los Angeles Daily News. Boddy was also a friend "of the Roosevelt Administration," and as such "his advice was often sought by the Administration on matters of national importance affecting the Pacific Coast." It was "by no strange coincidence," according to Brown and Merritt, that "when the publisher was asked for help and advice by the Administration on the handling of projected evacuation of citizen and alien Japanese," he "was the first to suggest their evacuation to the Owens Valley." Aware of the "plans outlined by a citizen group in the Valley aimed at developing a stronger economic position for the residents," Boddy also "knew the Japanese and shared none of the fears of the 'Yellow Peril' decried so loudly in front page banners" by the Hearst newspapers. Knowing "the temper of the California 'public,'" Boddy agreed "to aid the Administration in laying the groundwork for an orderly evacuation of the Japanese by the Army, and an orderly reception of them where they were sent)."

On February 21, 1942, two days after President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, Glenn Desmond, the public relations director of the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, called Brown, executive secretary and public relations director of the Inyo-Mono Associates (today known simply as Inyo Associates) organization that was promoting the valley's economic development through tourism, requesting that he travel to Los Angeles "for an off-the-record talk" with Boddy "on a matter of great importance." On February 26 Boddy told Brown and Desmond "that the Army had already decided on the Owens Valley as one place of 'detention' for as many perhaps, as 50,000 Japanese." He asked for suggestions on "handling the delicate relationship between the Army, the Department of Justice, the City of Los Angeles and the people of the Owens Valley." At the request of Attorney General Biddle, Boddy introduced the two public relations men to Thomas C. Clark, who had just been named by General DeWitt as Alien Control Coordinator and head of the civilian staff of the WCCA with responsibility for working out the preliminary organization of the evacuation. Evidently on Brown's advice, Clark chose to work with a citizens' committee that Brown would select. [3]

Following the meeting Brown returned to Owens Valley, enlisting the aid of some of its leading citizens. Among the individuals that agreed to aid in the endeavor were Merritt, a "rancher" near Independence and chairman of the committee on relations with the City of Los Angeles who was representing the people of Owens Valley in their discussions with the city "over land and Water." Merritt, who would serve as project director of the Manzanar War Relocation Center from November 1942 until its closure in November 1945, was a gifted agricultural organizer with a lengthy career in business, politics, and agricultural development. Since Merritt would play a significant role in pre-World War II Owens Valley history as well as the development and operation of the war relocation center at Manzanar, it is appropriate that his career, especially his relationship with the Japanese government, be examined.

Merritt was born in 1883 on a cattle ranch along the Sacramento River in Rio Vista, California. After growing up in Oakland, Merritt entered the University of California, Berkeley, in 1902. He dropped out of school after his freshman year to work as a cowpuncher for Miller and Lux, a large livestock concern with extensive landholdings in California, Nevada, and Oregon. Merritt reentered the University of California in 1904, becoming student body president in 1906 and graduating from the College of Agriculture in 1907. After graduation he served as secretary to the president of the university for several years, and in 1909 he was elected graduate manager of athletics. During 1911-13 Merritt served as vice president and general manager for Miller and Lux. By that time the company had acquired approximately 10,000,000 acres of land on which it raised some 600,000 cattle and more than 1,000,000 sheep. It owned a number of meat packing plants and was the largest distributor of meat and meat products in northern California. Merritt served as the University of California's first comptroller from 1912-17, organizing its business operations and properties and overseeing building expansion on the Berkeley campus. In 1917 he was appointed adjutant general of California, becoming chairman of the first civilian draft board in the state to oversee the draft during World War I. That same year Herbert C. Hoover, federal food administrator, appointed Merritt as food administrator for California, and in that capacity he was responsible for the state agricultural program and development of food supplies needed by the government. Merritt became a close friend of Hoover, working with him in the widely-heralded operation of Belgian relief. In 1919 Merritt returned to the University of California as its comptroller and served on the administrative board of the institution. In 1920 Merritt left the university to campaign for Hoover's presidential campaign After Warren G. Harding was elected President of the United States in 1920, Merritt opened a consulting and property management business in San Francisco. He purchased 1,200 acres near Wasco in Kern County to develop a commercial cotton-growing demonstration project. During the early 1920s, Merritt continued to be associated with the University of California, serving as its chairman of endowments and as its acting chairman of the Grounds and Buildings Committee. In the latter capacity, he supervised the first construction on the campus of the University of California, Los Angeles. In 1919 he became the director of the California Development Board, which would later become the California State Chamber of Commerce in 1929, and from 1925-28 he served as director of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. During the 1920s, Merritt also served as chairman of the first statewide water committee, playing a leading role in the Central Valley Project that developed a dependable water supply for the San Joaquin and Sacramento valleys. Other responsibilities of his during the 1920s included taking an active part in the campaign to reapportion the state legislature and serving as a member of the Bay Bridge Committee in San Francisco. In this latter capacity, he worked with Secretary of Commerce Hoover to lay the groundwork for the construction of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. Appointed to a federal agricultural committee by President Calvin Coolidge in the early 1920s, he worked with the War Finance Corporation to alleviate the crisis in sheep prices and with banking institutions to solve problems associated with marketing farm products. He became a leader in the field of cooperative marketing of agricultural products, helping to establish the California Rice Growers' Association and serving as its president during 1922-23.

In the latter year Merritt became president of the Sun Maid Raisin Growers' Association, a Fresno-based farm cooperative that stirred controversy in the San Joaquin Valley. He soon faced charges of violating anti-trust laws, but, as a result of his contacts with Harding administration officials, the indictment was dropped. He was with the Harding party during the president's last illness and death in San Francisco and helped with arrangements for removal of the president's body to Washington for funeral services. In 1924 Merritt and his wife went to the Orient to open markets for Sun Maid raisins in China, Japan, and the Philippines. During his visit the Japanese government proposed to award him with a medal and other honors "for having saved Japan at the time of its rice riots because the advent of the California rice into the Japanese market had quieted the rice riots and returned the people to a feeling that their kind of rice would be forthcoming." Although he declined the honors, Merritt developed significant relationships with Japanese government officials on the trip. While visiting Tokyo, word was received that the U.S. Congress had passed the Immigration Act of 1924 barring further Japanese immigration to the United States. In the wake of this announcement, violent anti-American demonstrations broke out as angry Japanese took to the streets. Merritt spoke to the crowds, promising to attempt changing the legislation if they would stop the demonstrations. Merritt would later say that this incident "began my interest in the Japanese people and my interest in trying to get this Exclusion Law and the [California] Anti-Alien land law stricken from our statutes. It finally led me to my part in the War Relocation Authority and being Director of Manzanar in World War II, the Presidency of the Japan America Society in Los Angeles in 1951, and my friendship with Crown Prince Akahito."

During the mid-1920s, Merritt purchased a vineyard outside Fresno to demonstrate his belief that vineyards should be removed and replaced by other crops to reduce the surplus of grapes and thus raise their "price" in domestic and foreign markets. The Sun Maid Raisin Growers' Association went bankrupt in 1928 and was taken over by its creditor banks. Following the financial collapse of Sun Maid, he went to Europe, broken in health, spirit, and finances. After his return, he worked with grape growers for a period, but soon suffered a severe attack of pneumonia. Merritt had relatives in eastern California, and had maintained a long-time close friendship with descendents of John Shepherd who in 1864 had homesteaded the land that would later form a portion of the Manzanar War Relocation Center site. Thus, Merritt retreated to Death Valley to recuperate under doctor's care in the early 1930s, later buying a ranch and establishing his home near Big Pine in Owens Valley. A long-time friend of Horace M. Albright who served as Director of the National Park Service from 1929-33, Merritt played a pivotal role in the effort to have President Hoover issue an executive order establishing Death Valley National Monument on February 11, 1933. Merritt began to speculate in silver and lead mining ventures in the Death Valley area and purchased additional ranch lands in the vicinity of Yerington in western Nevada. In 1937 he helped to found the Inyo-Mono Associates. [4]

Other persons in addition to Merritt that Brown contacted included George W. Savage, a resident of Independence and owner of the Chalfant Press which published the three major Owens Valley newspapers; Douglas Joseph, a Bishop merchant and president of Inyo-Mono Associates; R. R. Henderson, a lumber company owner in Lone Pine and chairman of the Inyo County Evacuation Committee; Inyo County Superior Court Judge William Dehy, one of the county's most respected citizens and a leader in the valley's resistance to the Los Angeles aqueduct during the 1920s; Dr. Howard Dueker, a medical doctor in Lone Pine, president of the Lone Pine Lions Club, and spokesman for medical aid and sanitation in Inyo County; and George Francis, a resident of Independence and District Attorney for Inyo County. These men, according to the Brown and Merritt report, "all saw the [Japanese relocation] program as a beneficial one to the area, but all of them also saw the difficulties ahead in handling public reaction." [5]

This "ad hoc" committee with Merritt as chairman was "asked unofficially" by Clark "to draw up a program for the Japanese which would be beneficial to the Valley" He also requested that they "aid the military in selecting a site" and "give advice to the military and to his office on the best and most timely way of informing the people of the Valley of the coming influx of people."

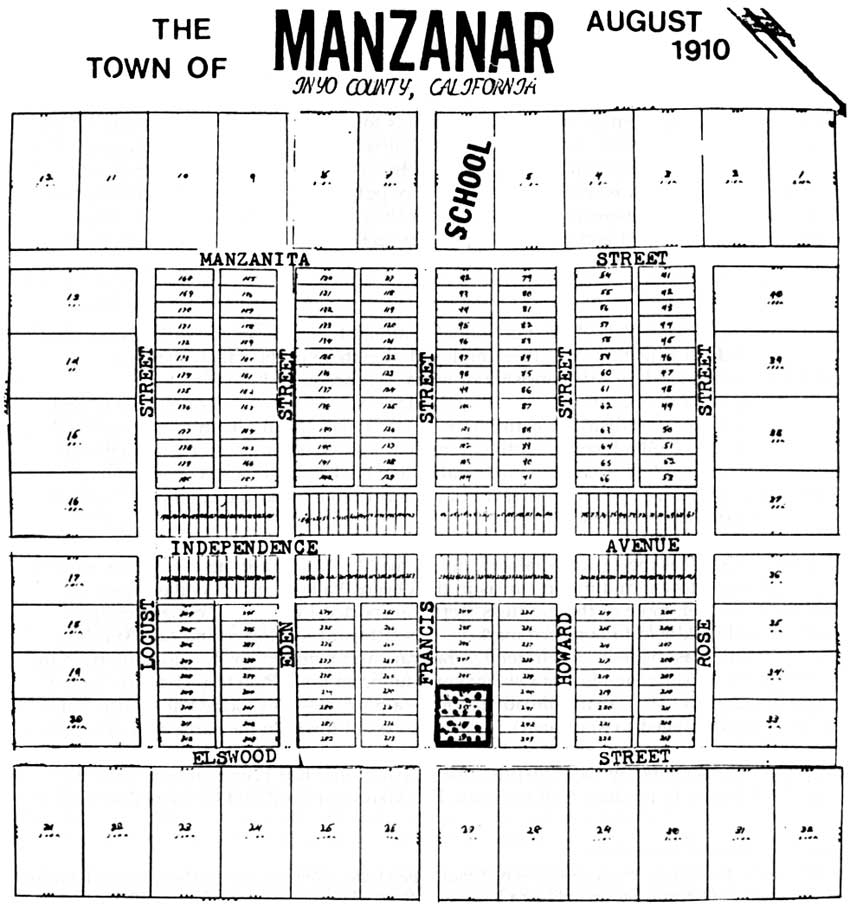

On February 27 Merritt and Brown, along with an Inyo County supervisor, accompanied "officers from the U. S. [Corps of] Engineers on a detailed tour of the Valley" during which several sites, including locations near Olancha and Bishop and one on the east side of the valley, were inspected. According to Brown and Merritt, the engineers selected a site on the west side of the valley between the towns of Independence and Lone Pine, primarily because of its relatively level ground and the water available from several streams which ran down from the Sierra Nevada. The location selected was the site of John Shepherd's 1864 homestead and of an early 20th century "irrigation colony" known as Manzanar, where portions of the drainage system and concrete conduits George Chaffey constructed were still in place. [6] In his report, Silverman stated that the military selected the site "because of its distance from any vital defense project (except the Los Angeles aqueduct), its relative inaccessibility, the ease with which it could be policed, and its general geography" The following day a first draft of a detailed plan "for the use of the Japanese and methods of handling public relations" was presented to Clark. [7]

A preliminary report on the Manzanar site was prepared on February 28 by Colonel Bendetsen and Lieutenant Colonel I.K. Evans but was not made public. [8] Confusion and controversy developed on February 28 when personnel of the Corps of Engineers "without consulting Clark on any method of approach on the delicate matter of public reaction, called on [H. A. Van Norman] the Chief Engineer of the Department of Water and Power." To "his utter consternation," according to Brown and Merritt, the military officials "demanded a lease on Department of Water and Power land in the Owens Valley amounting to 8,000 acres, for a 'prison camp' for 'Japs'!" Refusing the request, the chief engineer "started immediately to use his own influence in Washington to counteract any idea of the Army to use City-owned lands to house evacuated 'Japs'." Instead, he attempted to convince the Army that a site near Parker, Arizona, should be selected for a relocation center, and he tried to interest federal government officials, including the FBI, in the Japanese consulate's inquiry into the construction and operational details of the Los Angeles municipal water system in 1934, implying that the inquiry and subsequent hiring of 12 Japanese civil service employees by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power was part of a conspiracy by the Japanese government to sabotage the system. [9]

According to Brown and Merritt, this lack of coordination in handling the situation in Owens Valley prevented the "carefully worked out plan by all parties in the Clark agreement" from being presented.

Rumors began to spread through political circles in Los Angeles as well as the communities in Owens Valley, causing anxiety, fear, and anger. Anxious to get rid of its Japanese residents, Los Angeles officials nevertheless bitterly protested the choice of the Manzanar site. The vital aqueduct that carried water to Los Angeles originated in the Owens Valley and had been sabotaged in the past, and they feared that the Japanese would present a physical or sanitation threat, or both, to their water supply. Leading the attack against the Manzanar site was Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron and Congressmen Thomas F. Ford of Los Angeles, both of whom had consistently called for the evacuation and internment of persons of Japanese ancestry living on the west coast. Ford noted:

In my mind, I can see Tokio grinning with joy because of the opportunity this action will afford to sabotage the water supply of 1,500,000 people. I cannot penetrate the mind of the General [DeWitt]. He may have reasons for his action that are satisfactory to him, but I most vigorously protest this action as in my judgment as [an] inexcusable piece of stupidity. I sincerely hope that his military superiors in Washington will stop this move until a more thorough examination of the dangers inherent in the situation are investigated. [10]

Mayor Bowron, while reiterating his support for evacuation and internment, trembled to think of placing the Japanese in Owens Valley. Nevertheless, he added that if the Army really won't take anything but the Owens Valley" we "certainly can't stop them." [11]

Meanwhile, the residents of Owens Valley were also becoming embroiled in the heated controversy On March 3, for instance, the situation in Owens Valley was aggravated when a private contractor told a local garage owner that he had come to look over the area where the Army was going to build "16 miles of prison camps" for those "damn Japs."

To restore order Clark on March 5 asked Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron to call together members of the Los Angeles Board of Water and Power Commission, the chief engineer of the Department of Water and Power, publishers of the four Los Angeles daily newspapers, and the president of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce. At the meeting, according to Brown and Merritt, Clark "brought order out of the chaos by masterful handling of the situation and forceful presentation of the will of the government." Among other things, Clark emphasized that the Western Defense Command had determined that an area "of some 6,000 acres situated between Lone Pine and Independence was absolutely essential to the Japanese evacuation program." Press releases were agreed upon by all present that would be published in each of the major dailies the next day. In addition, Savage produced extra editions for his three valley newspapers that were published on March 6. [12]

Highlights of the press releases included the story that the former Manzanar site had been selected by the Army for a "processing station" or reception center to house 10,000 to 15,000 persons of Japanese ancestry. Bids for the contract to construct the center, however, had been opened the previous day. The public was assured that the military was in complete control of the project "for the time being at least." All rights of the county and towns in the valley would be fully protected. Clark was quoted to the effect that the center would be "a boon not a burden to the community." In his editorial comments on March 6, Savage pointed to all the good that could come to the valley from such a project, praised the federal government for its ability to work quickly, and complemented the City of Los Angeles for its cooperativeness.

While the publication of the press release helped to inform the local residents of the contemplated moves by the government, it did not allay the fears of many people nor did it stop the "growing crop of rumors." One local resident, for instance, became so excited over current rumors that he attempted to form a "vigilante" committee that mapped out a plan of defense for the town of Independence, some five miles north of the site of the proposed relocation center. The plan, according to Brown and Merritt, contained "all the old methods of 'Indian Fighting,' including a 'delaying action' from rock to rock as the band of 'defenders' were to fall back when being pressed by 'superior forces.'" [13]

On March 7 General DeWitt sent a letter to the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, formally informing it that the Army had selected the Manzanar site as a reception or relocation center site. He stated:

. . . . In order adequately to provide the means for orderly and rapid accomplishment of these [evacuation program] objectives, the immediate establishment of necessary facilities to care for persons excluded is necessary With the assistance of Federal, State, and local agencies a careful reconnaissance has been undertaken of possible sites for this purpose. Although many areas were suggested as immediately available, actual surveys on the ground revealed only two sites possessing all the features necessary and desirable for the intended use. Both of these sites are absolutely essential to the program. One of these sites lies in the area known as Owens Valley within Inyo County, California, the ownership of which is in the City of Los Angeles.

In view of the urgency of the situation, I have initiated construction of necessary facilities in Owens Valley near Manzanar upon property owned by the City of Los Angeles and within the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Water Works and Supply thereof Use of this property will be for so long as the present emergency requires, following which possession will be relinquished. Incident to the use of the said property, water in the watershed in which the said property lies will be appropriated in such quantities and for such specific purposes as may be necessary, fully bearing in mind, however, the needs of the City of Los Angeles for such water.

DeWitt "assured that adequate provision will be made and continued for protection of the Los Angeles Municipal Water Aqueduct and works appurtenant thereto against any injury or pollution by reason of the project." The general stated further:

I therefore advise you in the name of the United States Government that, effective immediately, temporary possession of the said property described . . . will be taken by duly authorized officials and agents of the United States Government for such uses as may be necessary

DeWitt closed the letter by stating that he Was acting under the broad powers of the Tucker Act under which the Army could take property necessary for national defense. Although not mentioned in the letter, DeWitt promised city officials during private conversations that the Manzanar site would be patrolled by military police. [14] On March 9 the Los Angeles City Council debated the question of the military's acquisition of the Manzanar site, determining to postpone a vote of endorsement pending further study. More than a year later on April 15, 1943, the city council, after acrimonious discussion, would resolve that the city's "agricultural lands and water in the Owens Valley may be made available to the Federal Government, conditioned upon the same being placed under agriculture and tilled by the internees at Manzanar, and the vegetables produced therefrom be made available to the armed forces of the United States or sold in the open market at prevailing prices to the residents of the City of Los Angeles." [15]

Although the military was taking physical possession of the land for the Manzanar relocation center, the legal issues involved had not been settled. The federal government filed a civil complaint for condemnation of the land "under the power of eminent domain" on June 27, 1942, based on authority given to the Executive Branch by the Second War Powers Act of 1942. [16] The US. District Court for the Southern District of California, Northern Division, granted to the United States immediate possession under a leasehold interest expiring June 30, 1943, for 6,020 acres. The order included all water wells and pumping installations in addition to the land. [17] The Western Defense Command and the City of Los Angeles disagreed on the annual payment that should be made for the use of the land, with the military claiming $12,000 and the city $25,000. The court decided in favor of Los Angeles and a "Declaration of Taking" was issued, granting the Western Defense Command the legal right to occupy and use the land "for a term of years ending June 30, 1944, extendable for yearly periods during the national emergency" and six month periods thereafter. [18]

Under the pressure of persistent rumors that continued to spread throughout Owens Valley, the "ad hoc" committee arranged for a series of public meetings to be held in the Lone Pine, Independence, and Bishop, the three principal towns in Owens Valley. Representatives of the Justice Department, the Army and the WCCA spoke at the meetings, outlining the government evacuation program, according to Brown and Merritt, "in such a manner that there was no possible chance of misunderstanding on the part of the residents." Acceptance of the program by the majority of valley residents, however, was another matter, as "racial intolerance" "made itself manifest." The Inyo County Board of Supervisors was antagonistic, in part because they had not been consulted by federal authorities. According to Brown and Merritt, most "of the residents of the county (population 7,000) having known each other on a first-name basis for a long time, infused personalities into the program from the beginning." Members of the "ad hoc" committee were accused of making "deals" with the government for personal gain, and the charge of "Jap lovers" was hurled in the town meetings in the valley. [19]

Following release of the first newspaper stories on the project on March 6, Merritt reconvened the "ad hoc" committee. An amended program of suggestions, with local problems and suggested means of solution, was adopted. The recommendations were taken by Brown and Savage to Clark at WCCA headquarters in San Francisco. Clark supported the committee's recommendations, and felt that the use of a local committee during the "first hectic days and weeks of this project and others like it soon to come was ne answer to helpful community relations in those communities where other camps were to be located." Thus, Clark formalized his appointment of the members of the "ad hoc" committee to the Owens Valley Citizens Committee with Merritt as chairman, thus giving that group "dignity and status in the community." [20] At the same time Clark urged Brown to leave his public relations work for the Inyo-Mono Associates and take over public relations work for the government at Manzanar.

He assumed his new position on March 15, the day after the first truckloads of lumber arrived at the relocation center site and the day when workmen began land-clearing operations for construction of the center.

In his report Silverman observed that local residents in Owens Valley "wanted no prison camps, it wanted no Japanese, and particularly it wanted no deal wherein any part of the City of Los Angeles was concerned." It took "nearly two weeks for the valley people to cool down, to realize this was a war and the acceptance of the so-called "prison camp" was necessary wartime sacrifice." A key change of heart in the valley occurred when George Savage had shifted his alarmism to the highroad of patriotism. In an editorial published in the Inyo Independent and his other valley newspapers on March 20, Savage now saw "History in the Making":

These changes were not of our asking, but the military necessities of war brought war to our own doorstep in an unexpected manner. Thus we see that the people of Inyo County have a definite part to play in the American wartime effort. Let's do the job so that the eyes of the nation and the world will be focused on the citizens of this county and outsiders will say that 'there's a group of people who are tackling a most strategic international problem and doing a great job of it." [21]

Furthermore, Silverman noted that "public opinion" was modified after "a group of leading valley citizens" received "tentative approval from the Wartime Civilian Control Authority (or so the citizens understood) for a series of public works projects which the Japanese could undertake for the permanent benefit of the valley." [22] Based on this understanding Merritt's committee met on March 30 and developed a set of proposals that were forwarded to Clark on April l. These included use of the Japanese internees at Manzanar for: (1) agricultural development; (2) broad gauging the railroad between Lone Pine and Mina, Nevada; (3) construction of mine to market roads for development of strategic materials and metals; (4) improvement of roads under a plan already worked out by the state Division of Highways; (5) development of small industries to be taken over by veterans after the war; (6) national forest and national park development and protection; (7) development of facilities for veteran rehabilitation; (8) development of wildlife conservation; and (9) other long range projects that may arise or have been planned by federal, state, and City of Los Angeles agencies. [23] Despite the initial support that the proposals received, however, they would never be implemented as a result of conflicts between WCCA and WRA and opposition by western state officials.

THE MANZANAR SITE IN MARCH 1942

When DeWitt formally announced the selection of the Manzanar site on March 7, 1942, the 6,020-acre parcel was described as a largely arid and barren patch of sand-swept desert. According to Silverman, there was "nothing left at Manzanar but a frowzy, dilapidated orchard of old apple trees surrounded by spotty stands of sagebrush, rabbit brush, and mesquite." Where a fruit packing house had once stood, "there was nothing but a stick or two of timber." [24] Although the property was desolate and barren, the vestiges of an apple orchard and mention of a packing shed indicate that the area had once been settled and farmed.

GEOGRAPHY AND HISTORY OF OWENS VALLEY

Natural Setting

The Owens Valley is the westernmost of the more than 150 desert basins which, together with the more than 160 discontinuous subparallel mountain ranges that separate them, form the Great Basin section of the Basin and Range Province of the western United States. Owens Valley is commonly defined as the narrow northwest/southeast trending trough bounded by the towering Sierra Nevada on the west, the White-Inyo Range on the east and extending northward from the Coso Range south of Owens Lake for more than 100 miles to the great bend in the Owens River northwest of Laws, California. The average elevation of the valley floor is approximately 3,700 feet. The valley includes the area drained by Owens River and its tributaries, and it contains two smaller topographic depressions, Long and Round Valleys. [25]

Geologic History

Throughout the Paleozoic Era the area of the present western United States was submerged beneath the ocean. It was exposed only at the shores of ancient Cascadia somewhere in the eastern part of the Pacific Basin. Erosion from the bordering lands and subsequent sediment deposition on the ocean floor, combined with the additional weight of volcanics from eruptions triggered by the growing stress of the deposits, led to the depression of a geosyncline at the western margin of the submerged region sometime in the early Mesozoic era, probably during the Triassic period. In the late Jurassic or early Cretaceous, this trough yielded to the tension. High temperatures and pressure caused the sedimentary rocks and volcanics to melt, and resulted in the recrystallization and granitization and emplacement of the Sierran batholith one mile or two beneath the surface (Nevadan orogeny) with aureoles of contact metamorphic rocks. These processes were followed by a rising of the trough. Erosion of the uplifted rocks exposed the granites with erosion continuing through and after the cessation of vertical movement into the early Tertiary. This period of relative quiescence was succeeded in the Eocene by a gradual up-arching of the eroded plain, probably along an axis through the area of the present Sierra-Cascade system. Some geologists tentatively place the movement along Owens Valley faults into this period. In the late Miocene and/or early Pliocene, the arch fractured into a number of segments. The Sierran black, remaining intact, continued to rise, tilting to the west. The eastern flank broke into a series of eastward tilted basin and range blocks, the westernmost of which was downdropped as the wedge-shaped graben that now forms the Owens Valley. Some geologists have suggested that the valleys to the east may merely represent alluviated areas on the lower ends of eastward tilted blocks, implying uplift without subsidence in this region. The downfaulting of Long Valley and Mono Basin is suggested to have occurred during this period as well, resulting from volcanic eruptions causing low pressure zones in these areas of local tension which in turn are attributed to the southward movement of the Sierra Nevada relative to the western Great Basin, including Owens Valley.

As a result of its geologic history, portions of Owens Valley, particularly the Manzanar-George Creek area, came to possess an isolated but magnificent natural environment. The formation of artesian springs and high water tables, together with fertile soil, resulted in this vicinity becoming one of the only areas in the southern Owens Valley to be suitable for agriculture. [26]

History

Exploration. Most historians believe that the first non-aboriginal people [27] to enter the Owens Valley area were American and English fur trappers and mountain men. Although early Spanish explorers may have discovered the area, no records of any such journeys have been uncovered. The Paiutes, however, probably had contact with travelers, judging from their rudimentary knowledge of Spanish. [28] Most evidence points to Jedediah Strong Smith as the first non-Indian to enter the region east of the Sierras in present California. [29]

After his exploratory journey across the Great Basin to southern California, Smith. who stands out as the epitome of the American combination of mountain man and explorer, came into contact with Mexican authorities who then laid claim to the present American Southwest. Disobeying his deportation orders, Smith travelled up the San Joaquin Valley. Faced with the need to return to a trappers' rendezvous at Great Salt Lake, Smith made the first crossing of the Sierra Nevada by a Euro-American during the late spring of 1827. The record of Smith's exact route remains unclear. However, most historians now believe that Smith crossed Ebbets Pass and either traversed the Antelope Valley or followed the Carson River northward, bypassing the Owens Valley vicinity entirely Nevertheless, his exploits encouraged later mountain men and explorers to journey into both the eastern and western Sierra Nevada of present California. [30]

The next Euro-American explorer to traverse present Inyo and Mono counties, according to several noted historians, was the British trapper Peter Skene Ogden. An agent of the Hudson's Bay Company based in the Northwest, Ogden has generally been remembered for his expeditions in the Great Basin from 1824 to 1830. Although his geographical descriptions are sketchy, some historians believe that his last trapping expedition in 1829-30 from the Columbia River to the Colorado River traversed Owens Valley and present eastern Mono County. [31]

Joseph Reddeford Walker, one of the most persistent explorers of the Sierra Nevada and Owens Valley, led three expeditions into eastern California. During the first expedition in 1833-34, Walker left the Great Salt Lake area, crossed the Great Basin, and travelled into the eastern Sierra in the first successful Euro-American effort to cross from east to west, While his exact route is not definitely known, most students of his travels suggest that he followed the east fork of the Walker River, perhaps traveled up Virginia Canyon, and crossed the Sierra somewhere in the vicinity of present Tioga Pass. After wintering on the California coast, Walker returned in 1834, some Indians guiding him over the pass across the southern Sierra that today bears his name. He then moved north through the Owens Valley, hugging the foothills of the Sierra. After passing through the valley, his party camped at Benton Hot Springs before turning eastward into Nevada. [32]

The Walker party's reaction to the eastern Sierra exemplified an attitude toward the land and the environment that would be echoed by subsequent generations of Euro-Americans. The expedition entered Owens Valley in late April 1834 and found the country not much to their liking. Zenas Leonard, a member of the party, described the region:

The country on this side is much inferior to that on the opposite side — the soil being thin and rather sandy, producing but little grass, which was very discouraging to our stock. . . . On the opposite side vegetation had been growing for several weeks — on this side it has not started yet. . . . The country we found to be very poor, and almost destitute of grass. [33]

The lack of pasturage and the harsh climate made the journey through Owens Valley slow for men anxious to get home, and probably affected their reaction to the valley. Significantly for its later history, numerous other exploratory and immigrant parties, most of whom traversed the arid Owens Valley during the harsher seasons, echoed Leonard's unfavorable reaction to the valley. Their negative comments, however, may have reflected, in part, an implicit comparison with western California and a lack of interest in lands that appeared to be a barrier to their final destinations.

Although westward moving Americans did not initially wish to settle on the barren lands east of the Sierra, they had to pass through them on their way to the mines and farmlands of western California. As a result the region began to be visited by passing wagon trains. In 1841 the first emigrant party to cross the Great Basin made its way into California. Sixty-four members of the Bidwell-Bartleson party left Missouri for California in spring. Internal dissensions divided the party, and half turned off on to a better known trail to Oregon in August. The others struggled toward the Humboldt River, still rife with conflict. They entered California passing through Antelope Valley, near present-day Coleville, in October, before following the West Walker River into the mountains and passing the crest of the Sierra in the late autumn somewhere in the vicinity of Sonora Pass. [34]

Joseph Chiles, a member of this successful crossing, returned to Missouri in 1842 and organized another group of emigrants. Hoping to avoid the hardships of the earlier group, he hired Joseph R. Walker to guide his party to California. Although Chiles later split off to find a northerly path, Walker led the bulk of the party through a portion of the Mono Basin, down the eastern shore of the Owens River, and over Walker Pass in 1843. The emigrants hauled their wagons, the first ever brought into California by overland homeseekers, and equipment all the way to Owens Valley, but to save their hard-pressed livestock they were forced to abandon much of their equipment near Owens Lake. After this journey Owens Valley became an occasionally used emigrant trail, providing a route into California that avoided crossing the High Sierra. [35]

John C. Fremont, a noted naturalist-explorer-scientist who became known as the "Great Pathfinder," ]ed a party through the Bridgeport and Antelope valleys on his "second expedition" in late 1843-44 during an unsuccessful effort to cross the Sierra in winter. Following this somewhat foolhardy adventure, he led a party into the Sierra during the late fall of 1845 on his third and final western expedition. While Fremont took a small band over the Sierra near Truckee, a larger party headed south under Joseph R. Walker, Edward M. Kern, and Theodore Talbot. The group passed east of Mono Lake through the Adobe Hills, striking the Owens River on December 16, 1845. Short on rations, the party hastened down the valley, leaving Owens Lake on December 21. The men crossed Walker Pass around Christmas and moved into the San Joaquin Valley to rendezvous with Fremont's group. [36]

Like the members of Walker's earlier party, this group also reacted negatively to the Owens Valley area. Edward Kern wrote in his journal that the area was "a sandy waste," lacked sufficient water, and provided poor grass for livestock. Kern noted a significant number of "wild-fowl," and was impressed by the "fine, bold stream," now known as the Owens River, but the "strong, disagreeable, salty, nauseous taste" of Owens Lake disappointed him. Kern spotted "numerous," "badly disposed" hidden Indians which caused apprehension for the party. [37] Needless to say, comments such as those of Kern and Leonard, did little to enhance the reputation of Owens Valley and Mono Basin. During this trip through the valley, Walker's third and last, the deep trough between the Sierra and the Inyo-White ranges received its name. Most sources argue that Fremont named the river, lake, and valley after reuniting with Kern, Walker, and Talbot. The namesake was Richard Owens, who like Fremont had never seen the valley One of Fremont's captains on his third western expedition, Owens was rewarded with this appellation. However, two historians, Philip J. Wilke and Harry W. Lawton, dispute this interpretation. Noting that Kern's daily journal mentioned "Owen's River" during the trek down the valley, and believing that the journal was written during the trip and not afterward, Wilke and Lawton have attributed the naming of the valley to Kern. Later, Fremont claimed credit for naming the river, lake, and valley in his Memoirs, published in 1887, during his only mention of the incident. In any case, the valley first appeared on a map under its present name in 1848. [38]

From the time of Walker's last journey to the late 1850s, many travelers passed through Owens Valley and Mono Basin. Most were on their way to western California, and likely viewed the arid lands east of the Sierra as the last obstacles in their journey. Various sources note the occasional presence of travelers in the area. In 1849, for instance, several groups of Midwesterners journeyed near Owens Lake during their crossing of eastern California, having suffered greatly while passing through Death Valley Other emigrant trains, using various passes through the Sierra to reach coastal and central California, continued to pass through the area on their way to the mines and new settlements springing up throughout western California. [30]

After California was admitted to statehood in 1850, the new state government became interested in the area east of the Sierra. In 1855 the state Surveyor of Public Lands commissioned A. W. Von Schmidt to survey lands east of the Sierra and south of Mono Lake. During 1855-56, Von Schmidt's team worked the area from Mono Lake to Owens Lake. The observations of Von Schmidt, like those of Kern and Leonard, probably served to discourage interest in settling the area. Like his predecessors, Von Schmidt found the region inhospitable. With the exception of Round and Long Valleys, he declared the "land entirely worthless. . . . On a general average the country forming Owens Valley is worthless to the white man, both in soil and climate." He noted the scarcity of game and observed that the valley "contains about 1000 Indians of the Mono tribe, and they are a fine looking set of men. They live principally on pine nuts, fish, and hares, which are very plenty." [40]

Although they had done nothing to whites settling in California, the Indians east of the Sierra were under constant surveillance by the U.S. Army and the Office of Indian Affairs after the late 1850s. In February 1859, 22,300 acres near Independence in southern Owens Valley were withdrawn from settlement pending a decision about establishing a reserve. That year both the Army and the Office of Indian Affairs made excursions into Owens Valley, thus affording whites a better knowledge of the area. During the year, Indian agent Frederick Dodge of the Utah Superintendency travelled through the valley, exploring the region and preparing a map as he went. [41]

That same year Captain John W. Davidson led an exploratory expedition through the region. After heavy civilian livestock losses were reported in the Fort Tejon, southern San Joaquin Valley, and Los Angeles areas, Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin L. Beall, officer in charge of Fort Tejon. ordered Davidson to lead a group of soldiers into Owens Valley to search for the stolen horses. Davidson, as well as many whites, had long suspected the Paiute of eastern California, but upon observing the natives of the region he concluded that such suspicions were incorrect. Finding few horses in the valley, he concentrated on observing the tribes and exploring the area, motivated in part by the prospect of establishing an Indian reservation on the withdrawn land in the valley as he had been instructed by Beall. Davidson observed that the Indians "are not only not horsethieves, but . . . their character is that of an interesting, peaceful, industrious people, deserving the protection and watchful care of the government." [42]

During July, Davidson's route took his group up the west side of Owens Valley to a point just north of Round Valley. Unlike most of his predecessors, Davidson was favorably impressed with the climate and much of the land. He found the climate "delightful." The soil, where "touched by water," was fertile and "well suited to the growth of weath [sic], barly [sic], oats, rye, and various fruits, the apple, pear, &cc." Grasses were "of luxuriant growth." In particular, Davidson found Round Valley to be "one of the finest parts of the state." To the farmer, it offered "every advantage but a market; to the Indian, nature, unaided by Cultivation, kindly bears on her bosom the means of his subsistence." He found "building timber enough for all the uses of a population commensurate with the agricultural resources of the valley." He noted an abundance of water in the region and suggested that much of the land could be irrigated from the many streams flowing down from the Sierra. Owens Valley and the Mono Basin were in his opinion "the finest watered portion of the lower half of the state." Davidson concluded that Owens Valley was an ideal location for an Indian reservation — the "country is large enough, & fruitful enough, not only for them, but for all the Indians of the Southern part of California." "Properly managed," a reservation "should cost nothing to the Government but the first outfit." After the first harvest, it "should be self-sustaining, for the means are here and nothing is lacking but their proper application." Despite Davidson's favorable report, however, the February 1859 order withdrawing acreage for a reservation was revoked by the government in 1864. [43]

The final state-sponsored exploration of Owens Valley during the 1860s was conducted by a Whitney survey team in 1864. Commissioned by state geologist Josiah Dwight Whitney, William H. Brewer led survey teams over uncharted areas of California during the early and mid-1860s. After surveying the Mono Basin area during the summer of 1863, Brewer's men reconnoitered Owens Valley during late July and early August 1864. The party traveled from Visalia over Kearsarge Pass, down Independence Creek to Owens River and Owens Lake, back upstream past Camp Independence, a military outpost established in Owens Valley in 1862, past the headwaters of the Owens River, and back over the Sierra. Brewer described the valley during his travels:

It lies four thousand to five thousand feet above the sea and is entirely closed in by mountains. On the west the Sierra Nevada rises to over fourteen thousand feet; on the east the Inyo Mountains to twelve thousand or thirteen thousand feet. The Owens River is fed by streams from the Sierra Nevada, runs through a crooked channel through this valley, and empties into Owens Lake. This lake is the color of coffee, has no outlet, and is a nearly saturated solution of salt and alkali. The Sierra Nevada catches all the rains and clouds from the west — to the east are deserts — so, of course, this valley sees but little rain, but where streams come down from the Sierra they spread out and great meadows of green grass occur. [44]

Throughout the trip in Owens Valley, which took place during a widespread drought in the state, Brewer and his party were uncomfortable in the dust and heat that frequently exceeded 100 degrees. Brewer noted:

It [the heat) almost made us sick. There was some wind, but with that temperature it felt as if it came from a furnace. It came from behind us and blew the fine alkaline dust into our nostrils, making it still worse.

Brewer failed to find any wood or other fuel. The cattle in the valley were "starving, because all but ten percent of the land, according to Brewer, was desert Mosquitoes were a nuisance, preventing sleep. Brewer's party was happy to depart the valley, taking with it an unfavorable impression of the area that would contribute to its reputation as an inhospitable area for settlement. [45]

Despite these impressions, however, Euro-American pioneers had begun settling in Owens Valley by the time of Brewer's survey. His mention of cattle and settlements in the region demonstrated the extent to which white settlement had encroached upon the valley lands that had hitherto been the domain of Indians. With the commencement of Indian-white hostilities in 1861, the federal government made its first imprint on the area with establishment of Camp Independence the following year. To get to the valley Brewer had relied on well-traveled prospectors' trails through the rugged Sierra. His reliance on those trails indicated the extent to which prospecting and mining was drawing Euro-Americans to the valley.

Mining. By the late 1850s mining strikes and production in the goldfields of western California and the Sierra were declining, leaving many prospectors unemployed and searching for new beds of ore. The mining industry itself had been reorganized with the realization that successful extraction required the discipline, money, and organization that capitalist methods could bring to the mother lode. As a result, the means of production became increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few, and many miners had to face the prospect of working for mining firms. Although this reorganization probably provided more security and success than the earlier individualistic and haphazard methods associated with independent entrepreneurial prospecting, some men sought to retain the independence they had envisioned in the west. Largely excluded from new strikes in the eastern Sierra, these hardy independents turned to the area east of the Sierra in the hope of independently striking it rich. [46]

The region of present Inyo and Mono counties appeared forbidding at first. Transportation and communication was difficult in the desolate and isolated region, the ores first extracted were not very high grade, and a lack of capital limited early development. Nevertheless, miners made their way to the inhospitable area, thus constituting the earliest Euro-American population in the area. [47]

During this period a series of gold and silver strikes drew attention to the semi-arid lands of the western Great Basin. The discovery of the Comstock Lode in western Nevada in 1859 stimulated great interest in the region. Yet Mono and Inyo attracted their own settlers, some prospectors arriving from western California and some traveling from Los Angeles. The Mono County area, in particular, was first populated by the overflow from the California gold rush in the late 1850s. [48]

Early mining strikes in present Mono County included Dogtown in 1857 and Monoville or Mono Diggings in 1859. Other strikes in the Mono County area included the discovery of gold at what would later become famous as Bodie in 1859 and discovery of silver east of present-day Benton in the early 1860s. These findings, however, were dwarfed by the larger, more fruitful strikes at Aurora on the Esmeralda Lode in Nevada in 1860. [49]

To the south, mining in Owens Valley began slightly after the establishment of Dogtown and Monoville. The greatest stimulation to mining activity in the valley resulted from nearby strikes, including not only those around Mono Lake but also those east of the valley. Prospectors from Los Angeles and from the western Sierra crossed the mountains to get to the valley. In 1860 Dr. Darwin French and his prospecting party discovered the rich Coso Ledges southeast of Owens Lake. That same year prospectors located the first claims in the valley in Mazourka Canyon, but did not develop them, and the New World Mining and Exploration Company, a San Francisco firm, explored the valley and staked claims southeast of present-day Independence. By July, nearly one hundred men were reportedly prospecting in the valley.

Enthusiasm for mining in eastern California soared during the early 1860s. In late 1861 the Mining and Scientific Press announced the success of mining east of the Sierra, declaring that its gold, and especially its silver, deposits would eventually provide "riches beyond computation." Although such enthusiasm would eventually have some merit, development of mining in the area proceeded slowly during the first few years as a result of hostilities between whites and Indians. After the Army was called in to quell the difficulties in 1862 and 1863, however, mining operations increased. Some of the cavalrymen found gold in the foothills of the White Mountains. In 1862, the San Francisco-based San Carlos Mining and Exploration Company, assured of military protection, established a camp between the Owens River and the mountains to the east. [50]

Virtually all of the first mining camps in Owens Valley were founded on the east bank of the Owens River. Owensville was established in the northern part of the valley in 1862 or 1863, some 50 homesteader claims being filed before 1864 when mining activity declined. By 1871 the last resident had departed, and the buildings were dismantled and the lumber floated downstream to Independence, Lone Pine, and Big Pine. [51]

Further south along the Owens River, three other mining settlements were established in the 1860s. each of them having a shortlived tenure. These communities included San Carlos, near the mouth of Oak Creek at the site of a soldier's gold discovery, Chrysopolis, and Bend City. The latter was a town that at its height included 60 houses, mostly adobe, two hotels, five stores, several saloons, a library, "stock exchange," and vigilante committee. [52]

Like the early strikes in Mono County, the first mining endeavors in Owens Valley amounted to little. Activity in the area remained slower than that taking place elsewhere in eastern California or western Nevada. Nevertheless, as miners entered the valley, the land was opened up to more permanent types of settlers. Visitors to the region noticed that the area could be used for agriculture and ranching, and the influx of miners and mining-related endeavors provided a market for dairy and beef products, farm produce, and the services of craftsmen and entrepreneurs. [53]

Settlement. The first recorded occurrence of Euro-American settlement in the Owens Valley region and its adjacent valleys took place in the Antelope Valley in autumn 1859, when Rod Raymond drove a herd of cattle to feed there. The following year George W. Parker homesteaded in Adobe Valley near the trail that connected southern California and Aurora. During the summer of 1861, the first white settlers entered Owens Valley. A cattle-driving party, including A. Van Fleet and Henry Vansickle, moved into the valley from the north in August, scouted the land as far south as the present site of Lone Pine, and returned to the northern edge of the valley to build the first white dwelling, composed of sod and stone, near the site of present-day Laws. About the same time, Charles Putnam built a stone cabin on Independence Creek, at the present site of Independence, as a trading post to tap the increasing traffic of prospectors through the valley. Samuel A. Bishop drove a herd of 500 to 600 cattle from Fort Tejon into Owens Valley and built a ranch southwest of the town that today bears his name. In late November 1861 Barton and Alney McGee herded some cattle into the Lone Pine area from the San Joaquin Valley and built a residence. [54]

After the first year of white settlement in the Owens Valley, three of the valley's four major town sites had been selected. Independence, known for a short while as "Putnam's" and "Little Pine," grew slowly, aided by the establishment of Camp Independence in 1862.

Thomas Edwards and his family, traveling with a large cattle herd, moved into the valley in 1863, purchased Putnam's trading post and stone cabin, and laid out the valley's first official town at Independence. Lone Pine prospered with the influx of miners, quickly attracting a multi-ethnic population. In 1862 several cattlemen from Visalia in the central valley settled on George Creek to form the nucleus of a community that would later become the orchard town of Manzanar. [55]

These nascent communities formed the loci for settlement expansion in Owens Valley. Yet the influx of settlers, and especially of ranchers and farmers, was not large. When the Army established its fort near Independence in 1862, there were few sources of food for the soldiers. Only in the next several years did sufficient settlers enter the valley to support a non-agrarian population. Thus, the driving force of permanence in the valley. and the bedrock on which valley development would be based during the next 40 years, was the settlement by ranchers and farmers that began populating the valley during the early and mid-1860s. [56]

One of the primary impulses for the rapid increase of farmers and stockmen in eastern California during these years was the drought that afflicted western California grazing and agricultural lands from 1862 to 1864. Searching for adequate pasturage for their stock, sheep and cattle raisers from the Central Valley drove their herds over Walker Pass into Owens Valley and northward into the Mono Basin. Later, while developing a route that remains in use today, herders pushed their stock over Sierra passes in Mono County into the northern part of the Central Valley, thus completing a circle of travel for summer pasturage. Some of these stockmen made their permanent homes east of the Sierra, while others continued making the summer journey annually, thus providing a steady stream of traffic through the region. [57]

Cattle and sheep proved to be the staples of agricultural production on the remote and semi-arid lands of eastern California. Expansion of farming operations in the area was hampered by lack of a reliable nearby market for produce. Nevertheless, the growing number of settlers had to provide for themselves, and they found a temporary, although unstable, market in miners and prospectors. While beef continued to be a staple for most diets, the expanding population in the region developed taste for a mixed diet of meat, dairy products, and vegetables. Thus, despite the primitive state of the region's economy, agricultural production expanded, and by 1867 some 2,000 acres had been enclosed with fences in Inyo County and 6,000 in Mono County Barley became the principal crop, but other foodstuffs were also raised for human and animal consumption. [58]

As mining and settlement increased in eastern California, governmental bodies were established. The early prospectors established mining districts with defined boundaries and drew up rules and procedures for staking claims and resolving disputes. Owens Valley and the Mono Basin fell within the jurisdiction of several established California counties, including Tulare, Mariposa, and Fresno, but the distance from those centers of government was so great and the means of transportation so difficult that the miners felt they needed their own governments. [59]

On April 24, 1861, the California legislature established Mono County as the first mining county east of the Sierra. Formed from parts of Fresno and Mariposa counties primarily, the county represented an attempt to bring governmental order to an area rapidly filling up with prospectors and mining operations. [60]

Residents south of Mono petitioned the California legislature to form Coso County in 1864 but the motion was not acted upon. Two years later, on March 22, 1866, the petitioners succeeded in establishing Inyo County out of portions of Tulare and Mono counties. At that time the southern boundary of Mono was moved up to Big Pine Creek, and four years later Inyo purchased for $12,000 another portion of Mono County, including the present town of Bishop, making the county's borders approximately what they are today. Competition developed between Kearsarge, a mining town high on the eastern slope of the Sierra, and Independence, near the U. S. Army post, for the honor of serving as the seat of Inyo County, but the latter was selected by county residents. After weathering dissension within the county that threatened to have its northern portion returned to Mono in the early 1870s, Inyo went on to become the second largest county in California. [61]

Hostilities Between Indians and Euro-Americans. The growing number of Euro-American settlers in eastern California led to tensions and conflicts with the Indians as the whites superimposed their settlements on lands that had long been inhabited by the native Paiutes. These bands of hunters and gatherers that belonged to the family of Great Basin Indians had suffered some of the problems of survival in that arid climate of eastern California but had also enjoyed the benefits of the river valley as their habitat. Until the late 1850s these people had lived largely secluded from the white man. Upon the arrival of growing numbers of Euro-American miners and settlers, however, the Owens Valley Paiute faced a severe and penetrating challenge to their centuries-old culture. [62]

In 1859, during his aforementioned expedition, Davidson had characterized the Owens Valley Indians as "an interesting, peaceful, industrious people, deserving the protection and watchful care of the government." Davidson went on to credit the Indians' indigenous agricultural practices:

They have already some idea of tilling the ground, as the ascequias [irrigation ditches] which they have made with the labor of their rude hands for miles in extent, and the care they bestow upon their fields of grass-nuts, abundantly show. Wherever the water touches this soil of disintegrated granite, it acts like the wand of an Enchanter, and it may with truth be said that these Indians have made some portions of their Country, which otherwise were Desert, to bloom and blossom as the rose. [63]

Davidson's observations were later shared by Colonel James H. Carleton of the First Infantry, California Volunteers, who described the tribe as both "inoffensive and "gentle". The supposition that these agrarian and food gathering people would not have the weapons and the hunting technology to make them dangerous to the encroaching white civilization would later surprise military officials when war broke out in the early 1860s. [64]

In 1859 Davidson not only recommended that Owens Valley be set aside as a reservation, but he also promised the Indians that their valley would be reserved, precluding whites from settling there. Provided that the Paiutes allowed free travel through the valley and that they "maintained honest and peaceful habits," Davidson was willing to protect them. It is likely that this plan had been approved, or perhaps suggested, by military and governmental officials far removed from the valley. [65]

Promises made by Davidson were reiterated by other agents of the Office of Indian Affairs. Warren Wasson, an agent with the Nevada Superintendency, reported in 1862 that the Indians had been promised security, material goods, and land by "officers of the government," presumably including both military and Indian agents. [66] In the Owens Valley, as in other areas east of the Sierra, the government had spoken too freely. Nevada's territorial governor, James B. Nye, reported in 1861, "the Indians have been promised too much, and led to expect more from their government than it would be possible to perform." [67] In the case of the Owens Valley Paiute, Nye's commentary proved prophetic. Once valuable minerals, grazing lands, and agricultural plots had been discovered in the area, the flow of white settlement could not be restrained by government promises to the Indians, and armed conflict resulted.

Tensions between Euro-American settlers and the Paiutes began to mount as miners and stockmen invaded Indian lands in Owens Valley, By 1863, the valley had become "a great thoroughfare. White cattlemen and herdsmen, hoping to feed their stock or sell it to miners in Esmeralda, Mono, and Inyo counties, drove their herds through the valley, undoubtedly the most passable route in the region. The sheep and cattle devoured the seed plants that the Paiutes relied upon for winter food, and the increase of lumbering in the eastern Sierra, as an adjunct to mining development and settlement, depleted the supply of pinyon trees, and thus pine nuts, a staple of the Paiute diet. Game, another staple of the Paiute diet, was depicted by the influx of miners and settlers. Not only did the Paiute lack an adequate food supply, but they also lost much of the surplus which they used to barter with Indians west of the Sierra for other goods. [68]

As tensions mounted in the early 1860s, word of the conflict began to spread. Neighboring Indian tribes and whites became acutely aware of the forthcoming hostilities. Colonel Carleton understood the problem rather clearly, observing that

the poor Indians are doubtless at a loss to know how to live, having their field turned into pastures whether they are willing or not willing. It is very possible, therefore, that the whites are to blame, and it is also probable that in strict justice they should be compelled to move away and leave the valley to its rightful owners. [69]

They rejected Paiute demands for tribute and appeals to move off their cultivated and gathering lands. Thus, the rift between the two peoples grew larger, pushing both sides beyond compromise or reconciliation.

The breaking point was finally reached during the winter of 1861-62. By felling pinyon pines for fuel, destroying seed plants and meadow lands with their stock, and depleting game, whites drastically reduced the natives' supply of food for the winter. Because of the particularly harsh conditions that season, the Paiutes virtually had no place where they could turn for food. When they began raiding the herds of cattle in the valley to replace depleted game, ironically capturing the very animals that had destroyed their seed plants, whites retaliated by shooting the Paiutes. Hostilities soon escalated. By joining forces under several leaders, most prominent among them Captain George from southern Owens Valley and Joaquin Jim from the north (a Yokuts), the Indians, by superior numbers, were in undisputed control of the valley by early 1862. The damage caused by the Indian raids was never made clear. It is possible that Indians may have been blamed for the thefts of other whites, as well as their own, because some whites probably suffered with the Indians that winter. In any case, the Indians that Captain Davidson had found peaceful in 1859 became hostile and feared by whites by 1862. [70]

Although most settlers, miners, and soldiers in the area hoped to put the Indians down forcibly, agents of the Office of Indian Affairs continued to work for peaceful resolution of the difficulties. During the spring of 1862, while early skirmishes were occurring around Bishop Creek, Indian agent Warren Wasson met Colonel Evans, who was leading the California Volunteers in the struggle to subdue the Indians. Wasson complained that his peace-making mission had been squeezed out by the military. His complaints were reiterated the following year by John P.H. Wentworth, Indian agent for the Southern District of California. After being turned down by Congress when requesting a $30,000 appropriation to subsidize and pacify the Paiutes, Wentworth lamented:

By heeding the reports of its agents, who are upon the ground and ought to know the wants of the Indians far better than those who are so remote from them, oftentimes formidable and expensive wars will be averted, and the condition of the Indians vastly improved. [71]

The military first appeared in Owens Valley during early 1862 after it received reports of troubles between the Indians and white settlers. A troop of California Volunteers arrived as the Indians laid Putnam's to siege in the vicinity of present-day Independence. Led by Evans, the troops drove away the natives and proceeded to Bishop Creek where a larger battle was underway. Following some skirmishing, Evans determined that a military post should be established in the valley to protect the growing numbers of white settlers. [72]

After a trip to Los Angeles to resupply his outfit, Evans returned to Owens Valley in June 1862 and established Camp Independence near the present-day county seat on July 4. Soon thereafter a short-lived treaty was signed with the Indians at the Indian agent's instigation, and the level of hostilities receded. As the supplies of both the Indians and the soldiers began to run out, however, warfare was renewed, especially after the soldiers and Indian agents could not provide the Indians with the material goods they had promised as part of the treaty. [73]

Armed conflict between the Paiutes and the whites extended into 1863, the military using increasingly brutal tactics to subdue the Indians. As Indian attacks increased during the early months of the year, choking off white traffic through the valley, soldiers and civilians responded harshly, killing and imprisoning the natives and destroying their homes and food supplies. Some white soldiers began taking advantage of Indian women, and the Indian women in turn looked to the whites for food and protection when their own tribesmen were deprived of the ability to provide for and defend them. Squaws began to stay around Camp Independence as early as 1862, angering the Indian men who had been undercut by white intrusions in the valley. Generally, the Indians fought on an "informal" basis, although during much of early 1863 they roamed the area in a band consisting of 150 to 300 warriors. A group of 41 Indians was exterminated on the shores of Owens Lake, just east of where the river flows into it, as revenge for the Indians' killing the wife and son of a civilian. Other pitched battles occurred on Owens Lake at the mouth of Cottonwood Creek, and in the Black Rocks area near Bishop. [74]

In the spring of 1863 Captain Moses A. McLaughlin replaced Colonel Evans as commander at Camp Independence. After ruthless pursuit of the Indians and decimating many of their homes and much of their food supply through a "scorched earth" policy, McLaughlin managed to subdue the Paiutes. Hungry and beaten, the Indians trickled and then poured into Camp Independence during the late spring and early summer until approximately 1,000, or slightly less than one-half of the estimated native population of the valley before the coming of the whites, had surrendered. Anxious to dispose of the beaten and troublesome Indians and to dismantle Camp Independence, McLaughlin, heeding the advice of local Indian agents, herded the Indians to San Sebastian Reservation in the southern San Joaquin Valley and Tehachapi Mountains near Fort Tejon, a military post that had been established in 1854 to suppress stock rustling and protect San Joaquin Valley Indians. Of the approximately 1,000 Indians who began the forced march, only about 850 finished it, those not finishing either dying along the way or escaping back to the valley that was their home. The escapees would be followed during the next few years by a large number of those who made the journey to the San Sebastian Reservation as the reservation and fort were ill-equipped to hold and provide for the people. These Indians gradually sifted back into the economy of the Owens Valley, living in rude and rocky camps along the fringes of white settlement and dependent largely for employment and sustenance upon the whites who had dislodged them from their homeland. The Indians, their former way of life largely decimated, began working for whites as farm and ranch hands and performing other menial jobs in the expanding white-controlled mining, ranching, and farming operations, while attempting to supplement their subsistence with some natural products. [75]

Although many of the displaced Indians returned to Owens Valley, their tribal ways were severely disrupted and their former social and familial structures all but destroyed. In 1870 a census counted 1,150 Indians an the valley, but by 1877 there were only 776, or about one-third of the estimated native population before the coming of the whites. [76]

When McLaughlin removed the Indians to Fort Tejon., whites assumed that the valley would be safer for their mining and agricultural pursuits. The development of these activities, which had been slowed considerably by the hostilities, accelerated. Nevertheless, some hostile Indians, who had not submitted to the soldiers, continued sporadic attacks against the white settlers. Camp Independence., which had been dismantled when McLaughlin returned to Fort Tejon in 1864, was reestablished to protect white settlers as well as travelers through the valley and remained in operation until 1877. With the reopening of the camp, most of the Indian attacks ceased. [77]

History

Development: 1860-1890s. With the conquest of the Paiute, the lands of the eastern Sierra opened up to rapid settlement and development by white Americans. During the last thirty five years of the 19th century, Owens Valley underwent substantial development that would shape its future and determine to a large extent its present character. Two prominent mining booms took place in the area — the strikes at Cerro Gordo and Bodie — that would dominate the history of the region. Before reviewing these mining booms, however, it is important to understand their historic context and their relationship to ongoing settlement and agricultural development. [78]

While the mining rushes had profound effects on the development of the Owens Valley region, they were primarily short-lived affairs. Agriculturalists began settlements that had a more permanent character, although even farms were but temporary features upon the landscape in some parts of eastern California. Initially, agriculture relied upon the market that miners provided, as did other industries that supplied lumber, transportation, and water. Despite this dependence, however, farmers and ranchers lent an air of stability to the lands east of the Sierras. The hard economic times that set in after each boom reduced agricultural interests but could not eliminate them as they did mining. The slumps in the region after 1880 attest to the difficulties in the economic sector that supported miners, but the persistence of farmers and stockmen attests to the steady character of livelihoods tied to renewable wealth of the land. [79]

Although farm operations got off to a slow start in Owens Valley, they expanded rapidly during "the late 1860s. By 1867 farmers were cultivating approximately 2,000 acres. Barley was the principal crop. Two years later, 250 tons of grain were harvested from 5,000 acres of cultivated land in the valley, thus indicating a rapid expansion in farm operations. By 1886, a variety of fruits and vegetables were being raised in the valley, bringing good prices to growers. [80]