|

MANZANAR

Historic Resource Study/Special History Study |

|

CHAPTER SEVEN:

EARLY DAYS AT MANZANAR — COMMENCEMENT OF CONSTRUCTION AND OPERATIONS UNDER THE WARTIME CIVIL CONTROL ADMINISTRATION, MARCH-MAY 1942

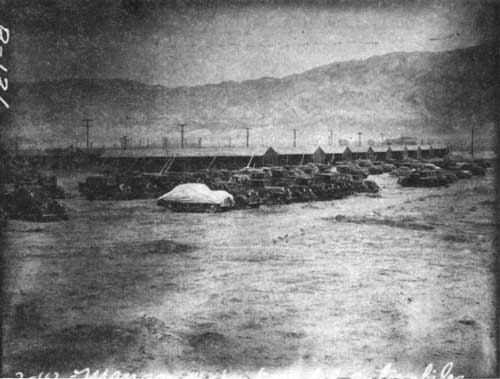

After the Army selected the Manzanar site to serve as the first reception or relocation center for Japanese evacuees in early March 1942, the Western Defense Command made hurried plans to construct the camp to house evacuees. Before construction of the camp was completed, evacuees began arriving at Manzanar in large numbers. Amid the chaos and confusion of this early period, the Manzanar center began to take shape under the direction of the Wartime Civil Control Administration, the civilian arm of the Western Defense Command. [1]

CONSTRUCTION BEGINS

As soon as the Manzanar site was selected, the Western Defense Command immediately developed plans to construct the camp. Since this was the first reception or relocation center to be built, neither the Army nor the WCCA had devised standardized construction plans. Nevertheless, specifications were hurriedly drawn up and bids for the general contract to build the camp were opened by the U. S. Engineer's Office in Los Angeles on March 5. [2] According to the Inyo Independent of March 6, three of the major contracting firms in the southwestern U.S. submitted bids. Although the contract was not located during research for this study, its specifications, according to the newspaper, included provision that 6,300,000 feet of lumber be delivered to the site within 30 days. [3] The military was interested in keeping construction costs for Manzanar as low as possible. As a result, the Western Defense Command prepared an "advance copy of a [confidential] directive for the construction of a camp for alien enemies in the vicinity of Owens Valley, California" on March 6. It was noted that this "general directive" was necessary in view of the fact that speed in construction is necessary and that it implemented the directives of Secretary of War Stimson to DeWitt on February 20, authorizing him to "take all necessary measures and incur necessary obligations for movement of enemy aliens." The directive was formalized by the War Department and transmitted by the Adjutant General's Office to the Chief of Engineers with authorization to proceed with construction on March 8. The directive set out the basic requirements for camps to house alien enemies. The Chief of Engineers was to "collaborate with the Commanding General, Western Defense Command, and take the necessary steps to initiate the construction desired by him in the vicinity of Owens Valley, California." Layout plans and location of the site would be "as determined by the Commanding General." The directive stated further that minimum requirements consistent with health and sanitation will determine the type of construction. In general, the facilities afforded by Theatre of Operations type of construction will not be exceeded. This project will be limited to a cost not to exceed $500 per individual.

During the course of deciding upon these requirements the military had consulted with personnel in the Works Projects Administration and the Farm Security Administration, because of their experience with development of low cost housing projects. The construction directive and authorization to proceed with construction was transmitted to the Division Engineer, South Pacific Division, in San Francisco on March 13 and to Leonard G. Hogue, the District Engineer in Los Angeles who would provide direct supervision for the work at Manzanar. On March 13 the Surgeon General was notified that the directive contained no "specific mention" of "hospital facilities to be provided." [4]

On March 6, Griffith and Company of Los Angeles received the general contract for construction of all temporary buildings and structures that were initially built at Manzanar, including installation of plumbing equipment and fuel oil lines. Lieutenant Colonel Edwin C. Kelton was the contracting officer for the Corps of Engineers, and the company, using building plans drawn up by the Corps of Engineers, worked under the supervision of Leonard G. Hogue, the District Engineer in Los Angeles. The company's contract representative was J. Hopinstall, while its representative at the construction site was C. E. Evans. [5]

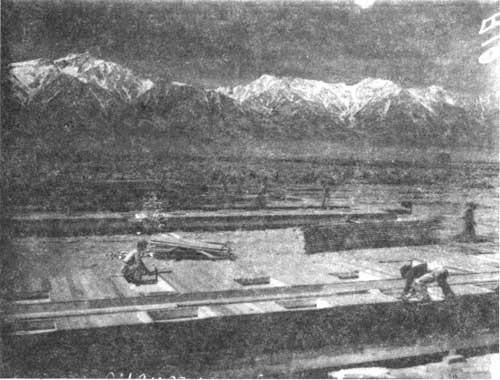

According to the aforementioned "Project Director's Report" by Brown and Merritt, the first truckloads of lumber began to arrive at the Manzanar site on March 14. The following day workmen began to clear the sage-covered land and dig the first ditches for water and sewer lines, and on March 17 the first buildings began to go up. [6]

As construction of the Manzanar camp began, the Wartime Civil Control Administration issued a press release on March 18. The statement, which was overly optimistic in tone and somewhat misleading in detail compared with actual conditions that the evacuees would experience, noted that brush "was being cleared and prefabricated houses were springing up today at Manzanar . . . where hundreds of mechanics, carpenters and laborers are constructing the first Japanese Resettlement Camp on the Pacific Coast." Complete facilities "for housing and caring for 1000 evacuees" would be completed "by the first of next week," and the camp would "house 10,000 Japanese when finished." Houses "for the resettled Japanese are of the 'family unit' type, in order that family units will not have to be split." The camp was expected "to be largely self-sustaining." Opportunities "for development of truck gardening and small industries — such as commercial fisheries and pheasant farms — appeared 'excellent.' " The camp was "ideally situated, away from the sandy soil near the mountains." The first contingent of Japanese would be put to work "clearing brush and building gardening installations." A 50-bed hospital, staffed by Japanese doctors and nurses, would be ready for the evacuees. Recreation facilities were being arranged "in the form of movies, athletic games and possibly university extension courses." Provision "for free religious worship of all denominations," including Buddhism, had been made. Since the camp would be "composed largely of voluntary migrants," officials expected "close cooperation from the Japanese on camp management." [7]

In his report that was discussed in Chapter Six of this study, Milton Silverman observed that on March 18 "Manzanar was in the painful, dusty throes of becoming a boom town. By March 19, he noted that "huge lumber trucks were roaring up the . . . highway from Los Angeles and 400 carpenters were already working a 10-hour shift." Soon a "hundred-foot administration building was standing where the old Manzanar packing house stood." Within "24 hours," the workmen started "on the first of 25 city blocks." The schedule "called for completion of one block a day." Silverman observed that

the workmen moved into action like an army of trained magicians. One crew led the way with small concrete blocks for foundations. A second followed with the girders and floor joists. A third came right along with the flooring, a fourth with prefabricated sections of sidewalls, a fifth with prefabricated trusses, a sixth slapped on the wooden roof, a seventh followed with heavy tarpaper, and an eighth finished with doors, windows and partitions.

All around them were other crews clearing and leveling the land ahead, excavating for sewer and water pipes, and bringing in truckloads of the prefabricated sections made in a centralized prefabrication mill only a few hundred yards away. At the same time, still other workmen were setting up the first of 25 oil centers to hold fuel oil, 40 warehouses and the barracks for military police.

The workmen had no time to build wooden buildings for themselves; they slept in a tent city.

During the early phases of construction the first complaints about wind and dust were voiced. According to Silverman, "over, under, and around and inside everything was the dust loosened by the tractors and scrapers, and blown by the interminable south wind. On mild days, the wind picked up only this dust, but it really worked up to a blow, it carried dust, sand, stinging bits of gravel and even white soda dust scooped up from the deposits at Owens Lake more than 20 miles to the south. [8]

In an article in the Inyo Independent on March 20, E. B. Milnor, assistant superintendent of Griffith and Company, stated that between 1,000 and 1,500 workmen would be employed during the peak construction period at Manzanar and that the weekly payroll of these men would average between $50,000 and $70,000. The workmen were engaged six days a week in 10-hour shifts in order to complete the center within 30 days. The article also noted that military guards were expected during the week "to put [the] district under surveillance." Clearing of trees and brush from the western portion of the center site was underway. City of Los Angeles personnel were working on water facilities. Water in the Los Angeles Aqueduct was cut off during the week, and a large sewer line was being constructed under the aqueduct. The sewer line led to a sewage plant under construction east of the aqueduct. Telephone crews were installing lines to the principal administration buildings and offices. Old irrigation ditches dating from the orchards that had been planted at Manzanar in the 1910s were being reopened, and grading of roads in the center was underway. The "entire project was abuzz, reminiscent of a three-ring circus." [9]

ARRIVAL OF FIRST EVACUEES

Less than one week after construction began, the first Japanese American evacuees arrived at Manzanar, which the military continued to call the Owens Valley Reception Center, on March 21, 1942, as part of the Western Defense Command's voluntary evacuation program. A WCCA press release dated March 21, the aforementioned reports by Brown and Merritt and by Silverman, and the Manzanar Free Press, the camp's newspaper prepared and written by camp evacuees under the direction of Robert Brown that began publication on April 11, 1942, provide information on the early arrivals, all of whom were from Los Angeles. While the descriptions of the early arrivals differ in some details, all provide insight into a hectic and chaotic period during which large numbers of evacuees were arriving at a partially-completed camp amid its frenzied construction.

In their report, Brown and Merritt briefly described the first arrivals at Manzanar by stating that on March 21 the "first 84 'volunteers' arrived by bus; the next day 6 more came by private car." The following day, March 23, "710 arrived in a caravan of private cars escorted by the Army." [10]

The WCCA, Manzanar Free Press, and Silverman each provide more information on the first contingents of evacuees to arrive at Manzanar. On March 21 the WCCA issued a press release that stated:

In striking contrast to the fleeing refugees in other lands, the first exodus of Japanese and Japanese Americans from the Western parts of the Pacific Coast states, starts in Los Angeles Monday morning, with a voluntary movement., in ordered arrangement, with military forces as escorts rather than guards.

Instead of pushcarts and wheelbarrows, or walking, the 1000 Japanese affected will travel in their own automobiles, in busses, and by train to the Manzanar Reception Center. . . .

The Los Angeles voluntary movement is the first mass departure from Military Area No. 1 in accordance with the evacuation decrees of Lieutenant General John L. DeWitt. . . . Other evacuations will be continued, to fulfill the Army's mission of minimizing sabotage and espionage in the critical areas of the Pacific Coast. . . .

Those leaving in their own car report at 6AM Monday at the South end of the Rose Bowl in Pasadena. They come prepared to start at 6:15, their tanks filled with gasoline, their tires and a spare in good shape, and prepared to buy their own gasoline enroute. Those going by busses report at 7 AM at 222 South Hewitt Street, Los Angeles. The train contingent will leave the old Santa Fe depot at 8 AM.

Each person will bring his or her bedding, except mattresses, tools of his trade, cooking and eating utensils, clothing and personal belongings, and a gallon of water. Those going by train can take what they can carry with them. Those using their own cars can carry what they can load into their machines. Each must care for his own belongings.

Under escort of troops, the caravans will travel in 10-car convoys. Two persons to a coupe or roadster, three to a touring car, and four to a truck are the passenger limitations.

Evacuees will have eaten breakfast when they appear for removal. They will be furnished a cold lunch enroute — and at the end of their 300 mile drive, or their train trip, a warm supper will await them, they will be comfortably housed, awaiting their establishment of community life and their later departure for permanent location under the War Relocation Authority. [11]

In his report, Silverman observed that while construction was beginning at Manzanar the "clamor for removal of the Japanese" on the coast "was rising still higher and the authorities could not delay evacuation" until construction "was complete." Thus, on March 21, "with only two blocks of buildings under way, the first contingent of Japanese — the "headquarter staff" — were brought from Los Angeles in three busses and a streamlined truck." These evacuees, according to Silverman, were "painters, and plumbers, doctors and nurses, cooks, and bakers, and stenographers with the job of preparing for the arrival of the first real group of evacuees two days later." These "first 86 arrived on a Saturday, but there was no week-end vacation for them." They worked "cleaning up kitchens, preparing a temporary hospital, organizing registration blanks, storing food, vaccines and blankets." On Sunday "they learned additional hundreds of evacuees were coming from Bainbridge Island, near Seattle."

Silverman went on to describe the arrival of evacuees at Manzanar during its first hectic days of operation. On Monday, March 23, the

first big group of Japanese left Los Angeles for Manzanar, 800 men who had volunteered to come early and pitch into the heavy work. One section came by train — a day-long trip that began at 8 o'clock in the old Santa Fe station near little Tokyo and finished at dark in the little Lone Pine Station 9 miles south of Manzanar.

The other section came by automobile — a 240-car caravan that started at 6 o'clock in the morning from the Pasadena Rose Bowl. There was every contraption in that caravan from a Model T Ford to a 1942 Chrysler. The cars were adorned with bedding, clothes, suitcases, ironing boards, washing machines, gardening implements, furniture, dishes, and mechanics tools. By official orders, every car contained a gallon jug of water and enough gasoline to run 300 miles. Some trucks carried delicately packed boxes of flowers and tomato plants, all ready for replanting.

Official orders likewise called for a limit of two passengers to a coupe, three to a sedan, and four to a truck. Each car had to have all four tires and a spare in good condition. The schedule allowed for a ten minute stop every two hours, but the schedule-makers were not actually so optimistic — they added an ambulance and a complete wrecking car to the caravan. Inserted into the line were a dozen jeeps, and before the day was over, many of them had to be transformed into diminutive tow-cars.

The army convoy was a military escort, officers emphasized, and definitely not an armed guard. They enforced driving precautions rigorously — particularly one which said no evacuee could get out of his car on the left-hand side — and the results were satisfactory; the caravan arrived in excellent condition. It, too was a slow all-day trip, with the speed cut down to accommodate the slowest car, and the evacuees reached Manzanar just at dusk.

Waiting for them were hot dinners, beds and a welcome from the 86 "pioneers."

For the next few days, the evacuees had not enough work, plenty of discomforts, and a snarl of misunderstood organization plans to unravel. The houses were almost finished, but the "almost" meant lack of windows, and that meant dust in everything. The showers weren't ready.

Silverman reported that one week later, on Wednesday, April 1, the Army "started the first load of the families to join the volunteer workers already at Manzanar. He noted that

a special train was prepared to leave Los Angeles at 8 o'clock (it left nearly an hour late), crowded with women and children and old folks, carrying baggage cars loaded with trunks, suitcases and 1000 lunch boxes. Two physicians were on board to take care of any emergency, but the only medical call came when one doctor cut himself trying to open a box; his colleague gave prompt and effective treatment. . . .

With 1000 expected to come on that first train and another 1000 expected on the following day, camp officials found their estimates were 40 per cent off. Only about 400 arrived on the first day [April 1] and 878 on the second [April 2]. [12]

In a special edition printed on March 20, 1943, the Manzanar Free Press commemorated the first anniversary of the camp's operation. An article in the anniversary issue described the first hectic days at Manzanar:

The first merry outburst of incredulity flooded around them on that cold afternoon of March 21 when 61 men and 20 women stood on the threshold of their future abode. There was nothing on the vast flat land before them except the groundwork of future homes that was having its inception. Within the first range of rough lumber was the skeleton of the simple, crude abodes which were soon to house 10,000 evacuees.

According to the newspaper, 35 of the first volunteers or pioneers had the task "of preparing something palatable from the potatoes and canned stew, hash, corned beef, etc., that were piled up heterogeneously where the police station now stands." Perishable foodstuffs, such as milk, were stored in two ice trucks at Lone Pine. Joseph R. Winchester, chief steward at Manzanar, went to Lone Pine daily with several evacuees to get food until the ice boxes were installed at the camp. Part of the "fun" at that time, according to Winchester, was "carrying 400 loaves of bread in his car for three days."

The newspaper article went on to describe the crude facilities encountered by the first evacuees to enter Manzanar. It noted:

The sewer until then [ca. early April] had consisted of a ditch, two feet wide and four feet deep extending from Block 1 to Block 6. An amusing incident was told of three evacuees who had become drunk on the way to Manzanar. They were walking around at dusk, having a happy time sobering up when they lost one member. Almost in vain they searched for him, when they espied him helplessly clutched by the ditch which had drenched him badly by the time five men succeeded in pulling him out.

The latrine for both men and women was an ungainly, "portable" outhouse, hooked up and dragged back and forth between the barracks. When its use was no longer needed, it was dragged up beyond Block 6, carrying a woman occupant who was trying vainly to get out!

Typical of the early evacuees were those who, having lost jobs or seeking adventure in an unenviable situation, had been eager to see what Manzanar was like. Eighteen-year-old Masiumi Kanamori . . . came with two other school friends, secretly harboring the idea of earning a little money, wanting to take in the new life from the start. . . . [13]

During April evacuees entered Manzanar in large numbers, swelling its population as camp construction continued. On April 11, for instance, the first issue of the Manzanar Free Press reported:

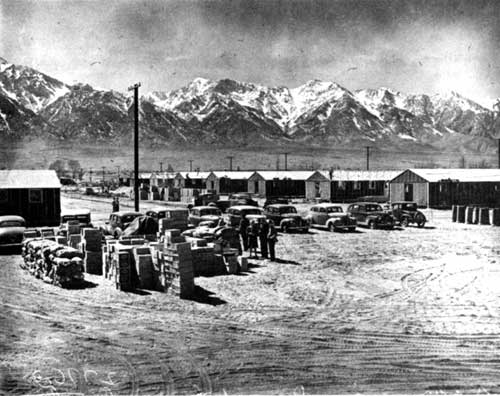

Pushing aside the sage brush and literally growing from the desert sand, Manzanar has mushroomed into the bonanza town of '42, boasting today a population of 3,302.

In 3 weeks this magic town has boomed ahead to become the largest city in Owens Valley — the largest California city east of the Sierras.

From the time when 85 hardy pioneers, including 8 girls, came from Los Angeles to stake out their new homes in skeleton buildings, additions and improvements have been constantly speeded.

Today 575 buildings are occupied. . . .

Hot water is already running in some of the showers and laundries and work is being pushed on the others. As additional blocks are completed, more contingents are anticipated to swell Manzanar. [14]

Two weeks later, on April 25, the newspaper observed that "3000 newcomers in the next three days climaxes three weeks of wondering when and from where the next contingents would arrive." These new evacuees, who would come from the Los Angeles area (Santa Monica Bay area, Sawtelle in West Los Angeles, and the Burbank and Glendale districts of the San Fernando Valley), would

find a cozier and cheerier welcome for during the three weeks' lull, carpenters and workmen were able to go ahead and complete steps and windows, washing facilities that will help make their adjustment. [15]

In the same issue, the newspaper reported that Griffith and Company would complete the camp in "a matter of days." With a construction crew of 600 men at work ten hours a day, 600 buildings had been erected to date. Proposed plans called for 770 buildings. J. Hopinstall, the company's contract representative, reported that "buildings are put up at the rate of two an hour and that 25,000 board feet of lumber are being used every ten minutes." [16]

ADMINISTRATION

Clayton E. Triggs was assigned by the WCCA as the first manager of Manzanar. According to Brown and Merritt, he had "a background of large scale camp administration, and years of administrative experience in the W. P. A. [Work Progress Administration]." Triggs brought "seven men who had been under his supervision on other jobs." The seven men opened the project and did all the work for the first few days. From the day the camp opened, Triggs administered Manzanar with the aid of what he called the "Strategy Board." This group, which determined all matters of policy for the camp, included Brown, the assistant director, chief engineer, and head of community services. The staff grew gradually with most of the individuals recruited from the WPA, a large-scale Depression-era national works program for jobless employables that was closing down.

One of Triggs' first goals, according to Brown and Merritt, was improvement of relations with Owens Valley residents. He worked closely with the Citizens Committee led by Merritt, and he, along with Brown, spoke at many service club and community meetings in the valley, outlining the work going on within the center. As a result of these public relations initiatives, some of the early hostility by local residents began to dissipate. Brown and Merritt observed that Triggs' efforts "began to bear fruit almost immediately." They noted that the

more members of the community began to feel that he was bringing the community in to having a part in the operation of the Center, the more the people began to take an interest in what was going on. The rumor-mongers found their audience dwindling away. The alarmists were laughed at openly. The change in community reaction was almost a complete right-about-face from the day of the first news announcement to the day of full operation some two months later.

This new feeling of acceptance and tolerance, however, would "change again back to resentment and distrust" later in the year. [17]

EARLY ORGANIZATION

The first service for evacuees at Manzanar was established on March 24, three days after the first evacuees arrived at the camp. This service, organized by Brown, took the form of an Information Office designed to issue, interpret, and translate the instructions and orders given by the camp administration to the evacuees. The office was staffed by five bi-lingual evacuees who were among the first volunteers to arrive at Manzanar. A bulletin board was erected in front of the office on which announcements, schedules, news, rules, and regulations were posted. It was also suggested, according to Brown and Merritt, that at a regular time each morning, "an assembly should be held at which "managers could make statements or give lectures to keep the boys informed and in good morale."

A messenger system, staffed by ten young evacuees, connected the evacuee barracks with the Information Office. These "runners rounded up workers" as they were needed for various jobs and facilitated communication between administrative officials and new evacuees.

According to Brown and Merritt, the Information Office was "the first attempt to organize and control the camp by self help." When evacuees arrived at Manzanar, they were registered and assigned to barracks. Their employment history was scanned by an employment officer, and those with basic skills needed to keep the camp running "in the emergency period" were assigned to supervisors and put to work. Such jobs included cooks, kitchen help, yard workers, garbage, and trash crews. There "was never any difficulty," according to Brown and Merritt, "in getting people to work even in the first days of the camp.

On March 25, the day after the Information Service was established, the first rules and regulations for the operation of Manzanar were issued in a memorandum by the Chief of the Service Division. These rules and regulations were posted on the bulletin board and concerned such issues as room occupation and food. Friends of the same sex over 18 years of age were allowed, with the permission of their parents, to live together. Males could not change their rooms without written permission granted by a designated administrative officer. Individual cooking in the barracks was not permitted because of the fire danger. At the same time, necessary bedroom equipment was promised to the evacuees, and it was announced that rice would soon be available in the mess halls. [18]

EARLY PROBLEMS AT MANZANAR

According to Brown and Merritt, the Information Office was the "switchboard" for channeling administration information to the evacuees as well as communicating questions and complaints from the evacuees to the administration. The first sampling of troubles voiced by evacuees was submitted to the administration on March 26 in a report prepared by the Information Office. The report included a list of 19 topics for which the Information Office sought information or clarification. Most of the queries centered around financial problems and concerns of the evacuees, what jobs would be available for evacuees at Manzanar, and what wages they could expect.

During the early days at Manzanar mail, money orders, checks, radios, telephone, telegraph, and other contact with friends and relatives outside Manzanar were topics of constant concern for the evacuees. Problems with expected or overdue baggage, lost or undelivered parcels, and requests for supplies needed in occupying the barracks, such as brooms, maps, buckets, and soap, took up much of the time of the Information Office. Problems and questions relating to cleanliness and health, recreational activities, and children's education were matters of continuing concern for the evacuees from the first days of the center's operation. As a result of these identified needs and concerns, many services and programs would not only be initiated at Manzanar but would also be incorporated "in regular operating charts for all the centers."

Brown and Merritt listed six primary problems faced by evacuees at Manzanar during the camp's early days of operation. These problems were: adjustment to center life, housing, latrine usage, financial concerns, vocational worries, and wages.

ADJUSTMENT TO CENTER LIFE

The Manzanar center was established to house some 10,000 evacuees. According to Brown and Merritt, all evacuees were housed in standard Army barracks which "did not differ in any detail," and all were "fed on a common diet to be served in mess halls," "Previously existing inequalities among Japanese were thus to be ironed out insofar as the standard of living was concerned." Brown and Merritt observed that "for the first few months, most inequalities were ironed out in the scramble for the primary, simple comforts of living." Until basic needs were met, there was little "struggle for leadership, power, prestige, or control of the camp — all of which came at a later date."

Housing

Housing was one of the principal concerns and complaints of the early evacuees to arrive at Manzanar. The lack of privacy in the barracks was a particular concern. Not only were unrelated families scrambled together, but often wives of other men were assigned to the same rooms with bachelors. Wives were sometimes welcomed at the gate by husbands who had preceded them to camp, and then the husbands would not be permitted to share their wives' quarters. While construction of the camp was underway during the early months of the camp's operation, changes could not be effected quickly. Even harder to endure was the forced company of people who did not belong to the family or who logically ought not to be assigned to a common apartment. According to Brown and Merritt, dictates "of decency and logic were violated by the pressure of population and the confusion of conditions because 10,000 persons were received in a little more than two months, and, during this time, the camp was still in the process of construction." On several occasions, "groups were sent in by the Army before the carpenter crews had windows, doors, or roofs on the block buildings to be occupied."

Latrine Usage

One of the most recurrent and emphatic complaints of the early evacuees at Manzanar related to the absence or scarcity of toilet paper in the latrines. Lack of privacy, according to Brown and Merritt, was also a "legitimate" complaint. Women particularly had difficulty coping with the "installation of an Army-latrine system" that provided no partitions.

Financial Concerns

Many of the early evacuees to arrive at Manzanar were concerned about payments for the upkeep of insurance policies, articles and goods bought on installment plans, and automobiles brought to camp. Most evacuees brought "problems in their wake which could not lightly be solved."

Vocational Worries

Many of the early arrivals at Manzanar exerted pressure on the administration to provide them with jobs. They had considerable idle time on their hands, and many had a strong work ethic. The evacuees were told early that they would be expected to work and that the center would develop "as a community in proportion to the interests and efforts the residents themselves were willing to put into building it." However, employment projects were slow in developing at the camp.

Wages

The first issue of critical importance to face center management, according to Brown and Merritt, was "over money." The first evacuees to arrive at the center received "an impression" that they "would be paid Army wages." This "probably stemmed from the fact that the Army was in charge of the evacuation, and that it did hire a number of Japanese in clerical and translation positions during evacuation." An Army officer had spoken to a mass meeting sponsored by the Maryknoll Fathers at San Pedro prior to evacuation. During his talk the officer left the impression that "Army wages were to be paid to those who would volunteer to go to Manzanar and make it ready for the others to come." In his first news conference, Triggs stated that he thought the evacuees would be paid "the old WPA wage with deductions made for room and board." The discussion of wages was reported in major metropolitan daily newspapers which the evacuees read at Manzanar, thus becoming a national issue which the evacuees followed closely.

Meanwhile, no decision was made by the Western Defense Command on wages for several months. In the interim, Manzanar center management asked the evacuees to "volunteer" their services to keep essential operations going. Many evacuees became disillusioned, believing they had been "promised" certain wages. Confusion and indecision on the part of the Army and the WCCA over wages, compounded by failure to receive any pay for three months, led to the first charges of "broken promises" by the evacuees. The "broken promise" charge, according to Brown and Merritt, was "an important turning point in the story of Manzanar as it was this weapon which was used by the anti-administration and so-called pro-Japanese forces six months later to stir up the turbulence which resulted in the 'Incident' of December 6." [19]

EVACUEE EXPERIENCES

While Manzanar was under construction and during the period when its first evacuee residents were arriving at the camp, the Los Angeles newspapers described the center in glowing terms. On March 30, 1942, for instance, the Los Angeles Times reported:

If Uncle Sam's children trapped in Japan by the outbreak of the conflict fare one-half as well as Japanese whom the fortunes of war and the will of the Western Defense Command place in Owens Valley. they will have reason enough to disagree with Sherman's opinion of armed conflict.

The present and prospective Nipponese occupants of the fast-building Owens Valley Reception Center at Manzanar are lucky They couldn't be censured for hoping, in their own behalf, that the war lasts for years.

Owens Valley, potentially one of the most fertile in California, and that means all the world, has the makings of a garden spot to supplement its natural attractions.

They couldn't wish for better scenery or a cleaner, more healthful atmosphere. [20]

The Manzanar Free Press, which generally took a pro-government stance in its commentary on evacuation and camp life, offered somewhat contrasting observations regarding the experiences of the first evacuees to arrive at the camp. In an editorial on May 2, 1942, the newspaper noted that evacuees "arrive in Manzanar with a mingled feeling of uncertainty and bewilderment." "Sooner or later," however, "the snow-capped High Sierras imbue us with complacency which makes us forget the bitter war now waging ever nearer our shores." The editorial stated further that as "a protective measure executed by the Army, we were moved as a collective racial group — far from the industrial centers." "Some are inclined to be bitter, for being moved from homes and friends." "Many have suffered financial losses." Nevertheless, prolonged "idleness makes people forget worldly cares and tribulations." Thus, all residents "must pitch in and make our camp life really worth while." [21]

With the aforementioned observations and commentary in mind, this section will provide insights into the experiences of evacuees during their removal to Manzanar and the early days of the camp's operation by focusing on representative eyewitness accounts. The experiences not only had a significant impact on the outlook and attitudes of the evacuees during the early internment period, but they also laid the foundation for serious antagonisms that would plague the center's operation throughout the war.

Pre-Evacuation Rumors About Manzanar

The arrival of the bulk of evacuees at Manzanar brought to light the fact that the majority of them had been subjected to rumors in the pre-evacuation period that would have a negative effect on their first experiences at the camp and thus contribute to their disillusionment during the chaotic early days of its operation. On April 14, 1944, Morris E. Opler, a community analyst assigned to Manzanar by the War Relocation Authority, prepared a summary report on pre-evacuation rumors about Manzanar and their effect on its evacuee residents. His report was based on interviews with three unnamed evacuees from the Los Angeles area. According to Opler, the rumors were "evidently general" in the metropolitan area, because the three persons were from three different and widely-separated parts of the city. The importance of "recapturing such evidence," according to Opler, was that attitudes and impressions "which are formed under strong emotional stress perpetuate themselves in various forms and are often found to have relation to events which afterwards occur.

Among the most drastic pre-evacuation rumors, according to Opler's "interviewees, was the story "that we were being put closely together, concentrated in a narrow valley between two mountains along an airplane route, so that if the coast was attacked by Japan we could be bombed and all killed." Another story was that they "would open the reservoir on us and drown us all." One interviewee observed: "People expected to get killed; I expected to die here."

As a result of some stories, the evacuees brought many non-useful items to Manzanar. Rumors circulated that the site was "full of big, biting ants and snakes," prompting many persons to bring bulky boots. There were rumors that Manzanar was inhabited by swarms of big mosquitoes and that you couldn't get any sleep at night unless you brought mosquito netting." One evacuee noted: "I still remember how I ran around trying to find some. And we all got plenty of it because we understood that the beds were in tiers, one above another, so that you had to have enough to reach to the floor from the top."

After the first evacuees arrived at Manzanar, rumors started in Los Angeles that men and women were forced to use the same showers and bathe together. As a result, "nearly all the girls and some of the boys brought bathing suits." One of Opler's interviewees had also packed a "big wash tub" and had it sent to the camp. Because of rumors that Manzanar was "full of thieves," the evacuees "stocked up on and brought along" "chains and padlocks and hasps for the doors." Rumors had it that "you had to get long chains and string all your suitcases together; if you left one by itself it would disappear."

Because of rumors that Manzanar did not have sufficient supplies of medicine and cotton, many evacuees brought large quantities of medications with them. One interviewee told Opler:

I had so much of the stuff that I couldn't get it all in my hand baggage and carried some in a wooden box. At the train the M.P. wanted to throw it out because he said the rule was that nothing but hand baggage was allowed on the train with the passengers. I told him it was my medicine and begged him to let me keep it and he finally did, but many people who brought wooden boxes to the train had them thrown off.

Even though there was medical attention here I found that much of this medicine didn't last long. At first they had no partitions in the latrines, just toilets in a row. Some of the women were so ashamed they wouldn't go to them and got sick. I gave out lots of medicine, ex-lax and things like that.

Rumors that all camp laundry was to be sent to one facility outside the camp led to the belief that everyone needed to put their "mark" or "initials" on every piece of clothing. Thus, prior to evacuation many evacuees "went around trying to get the proper ink so that they could put laundry marks on their clothes." Ink supplies quickly diminished. Thus, some evacuees sewed their initials on every piece of clothing they took to Manzanar. After the evacuees arrived at Manzanar, they were told that those "stories were started so that the stores in Little Tokyo and in downtown Los Angeles could sell their stock." One evacuee had purchased so much ink that he "was in a hole financially when I got here." Just prior to evacuation one "couldn't get rope, tags and many other things in Little Tokyo or "in stores of the Boyle Heights district."

The evacuees also told Opler that when they went "to the regular places [civil control stations] to ask what to bring" they were given inaccurate or misleading advice. For instance, they had been told that curtains and furniture would be provided at camp and thus such items should not be taken to Manzanar. When these items were not furnished to them after their arrival, they became disillusioned.

Concerning the issue of clothes, the evacuees told Opler that "no one did the right thing." One interviewee, for instance, related:

Mayor Bowron of Los Angeles made a speech in which he said that we were all to be put to work raising soy beans for the army So I made sun bonnets and packed away all my good clothes. Practically no one brought along good hats or shoes. About the only thing that people brought were slacks and rough work clothes. The mother of one girl I know sold her good dresses for 5 cents a-piece to Mexicans. Some of these were expensive silk dresses. People had the idea that they didn't need such things. They had the idea that they were going into another world. People didn't seem to look ahead. Because they were told to bring only what they absolutely needed at the time, they brought summer clothes only For the first year everyone wore slacks. Perhaps it was a good thing while the dust was so bad and before the place was settled. But as these things began to wear out, instead of patching them, as could have been done, people began to make or buy new clothes and dress up. . . .

Prior to evacuation, rumors started that Manzanar did not have sufficient water supplies. Thus, some evacuees brought innumerable bottles of water, some of which were whiskey bottles. Opler observed that his interviewees told him:

They tell of some boys who were sitting by some of these bottles which had been thrown in a ditch. . . . Some M.P.'s accused them of having whiskey. They couldn't convince the M.P.'s that it was just water in the bottles and had to go to the police station with them till it was straightened out.

Based on rumors that spread through the Japanese community in Los Angeles prior to evacuation, some parents were "greatly worried about bringing their daughters up here where everyone lives so close together." After the first group had arrived at Manzanar the parents in Los Angeles heard that "the bachelors and the loafers from Hawaii who used to hang around the drug store at San Pedro and 1st Street were up here and were doing bad things (raping) the girls." The parents were warned "to be very careful with their daughters and not to let them go anywhere alone at night."

The interviewees told Opler that it "was a relief to learn that these rumors were not true, but there were disappointments the other way too." Some of the things which happened in the early days of the camp's operation were "almost as bad as the rumors." As an example, one evacuee observed:

I came in the middle of May, 1942. Our baggage was put out in the firebreak by block 13. The baggage of one person often was not all together. A piece would be here and a piece would be there, It was hard to locate your luggage and get it together. The M.P.'s came to inspect it. There was a terrible dust storm that day If you weren't there to open the piece of luggage they would break the lock and go through the contents. The wind was blowing things all over and people were running here and there trying to take care of the belongings. Everything got dirty and all the people were angry. [22]

'Early Days at Manzanar' (By an Evacuee)

In a foreword to a report on an interview with an unnamed evacuee concerning the early days at Manzanar Opler observed on April 25, 1944, that many "of the present attitude sets and the convictions of evacuees are fully explicable only in terms of events and conditions which prevailed during evacuation and during the early days of the Center." Opler noted that "habits of mind which still persist" were established during the evacuation period and early days at Manzanar. These habits had developed as a result of the "effects on attitudes toward work," the "indecision, wrangling and false starts over wage scales," the "petty dishonesty and hypocrisy which arose over the failure to provide furniture or an openly approved way of constructing any," and the "unwillingness of the evacuee to assume responsibility for directions when their execution may bring him into conflict with other evacuees." He observed that the "psychology seems to be that, as a result of evacuation, a fundamental opposition obtained between the government, represented by the Center administration and the appointed personnel, and the evacuees. The enforcement "of any unpopular ruling, no matter how plainly it fell in the line of duty, subjected the individual to the criticism that he was siding with the administration and the government against the Japanese people." The "tremendous concern of the average evacuee over unfavorable comment and gossip directed against him made it almost impossible for the person to perform tasks objectively as he would have done in a less charged atmosphere." What the administration desired "was constantly weighed against what was considered to be the wishes and attitudes of the people." Where "the interests were not deemed identical, performance and cooperation were poor." These attitudes formed during the early days at Manzanar would continue "to exist until greater confidence in the government" was restored." Thus, it was important, according to Opler, to examine the experiences of evacuees at Manzanar during their evacuation to the camp and its early days of operation.

The evacuee that Opler interviewed had arrived at Manzanar on April 2, 1942. Concerning his induction at Manzanar, he stated:

I was on the last bus which transferred us from the train that brought us from Los Angeles to Lone Pine. The last bus pulled into Manzanar about five-thirty P.M. I was told to register at the Block 5 recreation hall. There I was assigned an apartment for my family and we were assigned some blankets. . . .

We slept that night with just the army blankets that were issued to us, for our bedding was checked in warehouses and the bedding was not to be distributed till the following day.

I awoke at the crack of dawn and got ready for breakfast. I don't exactly remember what I had for breakfast but I do know that in those early days of evacuation, food was pretty good, as rationing hadn't begun yet.

I wasn't any too anxious to work or to look for a job as we were told that the wages were to be $21 a month and each person would have to pay $15 subsistence. This meant that in my case, even if I did work, I would still owe the government $24, as I had to pay for my wife and son. I said to myself, 'Heck, I might as well not work at all.'

After breakfast the evacuee went to get his baggage. He noted:

Prior to evacuation I had rigged up a two-wheel pull-cart in order to carry the heavy baggage to the station. When we left Los Angeles I had to handle the baggage of three. My wife was pregnant and couldn't carry anything much and the boy was just a tot and couldn't carry anything. . . . I had this two-wheeler still and tried to use it now at Manzanar. But this contraption did not do much to alleviate the baggage problem as it was sandy all over and then again there were the sewage pits to cross. I discarded the cart and had some friends help me carry the baggage from the warehouse to the apartment.

After getting partly settled in our new home, I walked around looking for the lake that some Caucasian friends had told me about. They had mentioned that I was going on a nice vacation, as Manzanar was situated beside a lake, and that I could go fishing, swimming, and boating. In the winter, they told me, there was skiing to enjoy in the mountains. This sure turned out to be a sour joke to me for none of those things were available to us.

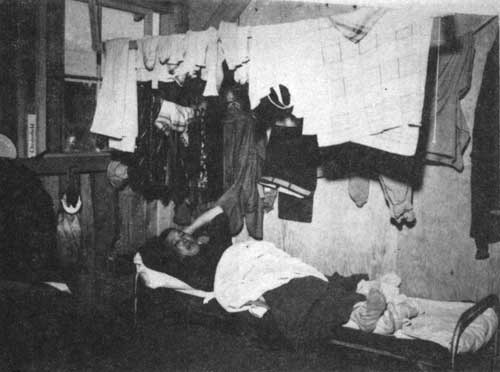

I was rather disappointed at the barracks which we evacuees were to live in. I thought at least each individual family would be assigned to a separate apartment. Instead, two or three families were crowded into a six beam apartment, offering no privacy. It didn't matter so much with the bachelors or the single girls if they slept in quarters together. But when two or three families were placed in one apartment to make the quota for the barrack, it was terrible.

As for the facilities, at first we had to endure the telephone booth type of latrine, which had a chemical task receptacle. When the wind blew, which was often, it blew right through the latrine. Sometimes it blew so fiercely that it seemed as if the latrine would be toppled over. I'm not exaggerating when I say this. At this time the present flush toilets were not ready from Block 3 on up to Block 12. The other blocks were not even built yet.

As for showers, hot water was only available in Blocks 1 and 2, as the volunteer groups lived there. We lived in Block 4, so we could not bathe every day as it was pretty far to walk in those days. By the time we bathed and returned home, we would catch cold. In due time, the boiler was installed in our block so we were able to bathe regularly. It was about two weeks after we came here, though.

We felt pretty leery walking in the night to the latrine, and there were snakes all over. The thought of stepping on one was enough to send a chill up one's spine. I suppose the evacuees from rural districts didn't think anything of it, but we who were raised in cities didn't feel just right walking to the latrine at night.

All the barracks in those early days were bare, and when the wind blew, the dust would seep right up through the cracks in the floor and through the walls, the ceiling and all over. The construction of these barracks was of the cheapest and simplest type. Even though there was a partition between apartments, you could distinctly hear the neighbors voices and their snoring too. Talk about sand! After walking all day, my shoes used to be full of it. If I had watered my shoes, I might have been able to grow thistle weeds. This sand is very hard on leather soled shoes and it really wears them out fast. We had to sweep the room every so often and mop once or twice a day because of the sand which was tracked or blown into the house.

The administration told us to mop at least once daily and to keep everything off the floor — at least six inches off the floor. Now, how were we to keep our belongings six inches off the floor if we had no lumber with which to build stands? Every time we mopped we had to put our belongings on top of the beds. We were told not to take lumber scraps or otherwise we would get into trouble. The administration promised us furniture at that time. I couldn't believe this promise so I gathered scraps of lumber from here and there and tried my best to build some crude furniture for the home. . . .

The evacuee described the somewhat primitive early medical facilities and treatment provided to residents at Manzanar. Among other things, he stated:

The hospital was housed in Block 1-2-2, a two-bed hospital at that time. The clinic was located in the next room, 1-2-1. The doctors then were Dr. G. and Dr. T. They deserve a lot of credit for their untiring medical aid to the evacuees. In spite of the lack of facilities and equipment they performed surgery and gave constant medical attention to the sick.

As more evacuees came, the hospital began to take up most of Block 7. There were residents in Block 7 but they were moved elsewhere to accommodate hospital patients and to provide larger rooms for surgical and clinical work.

Dental work was established rather late as there was no equipment at first. . . .

The evacuee observed that the camp's administrative staff was housed in Block 1-8 during the early days. He commented about the first canteen:

At first the canteen was run by a Caucasian group as a branch of the Fort Ord canteen. During those early days, the canteen had a tremendous turnover in business. The canteen was located in Block 1-9-4 and it was jammed full from the time it opened until it closed.

After the WCCA had determined the wage policy for the camp, the evacuee joined the Manzanar police department. He described some of his experiences on this job:

I then took a job on the police force as one of the patrolmen. I took this job principally because I thought I would get a uniform and shoes and a horse on which to ride around the Center. This job as policeman had many drawbacks, such as constantly having to tell new evacuees, and old ones too, not to go beyond certain boundaries. Thus we created enemies.

The unoccupied barracks were constantly frequented by lovers at night so we had to patrol the lonely outposts and stop those things. I know how young couples feel when in love, so I did not discourage them but told them to keep off my beat. There were many complaints coming in to the police stations about such conduct so we were 'elected' to stop them if we could.

On the police force we worked eight full hours a day with one day a week off. Those who worked at the desk usually got Sundays off. There were three shifts, with each crew going on single shift two weeks before changing.

Imagine working from midnight on till eight in the morning! I felt as if I worked two days instead of just eight hours during that shift. It was one of the most thankless jobs, but I managed to stick on until I found out there was no chance for promotion. I tried pretty hard, but I guess I didn't have the right connections, for newcomers got better ratings than some oldtimers.

It sure seemed funny when we had orders to apprehend any lumber thieves. Here were most of us taking lumber to build furniture for our own homes. This was a bone of contention between the evacuees and the police force.

Then you ran into things like this. There was an instance when we had orders from the hospital to keep all visitors away from the hospital between certain barracks where the contagious disease cases were. One woman had a daughter who was sick with measles and the mother was staying with her child during the period of quarantine. This was supposed to be two weeks. Long before it was over I saw her in Block 15, waiting with the crowd for the new incoming evacuees. She had no business there but what could I do? I didn't want to create a scene as I knew this woman was a blabber. Fortunately the doctor saw her and told her to go back to the hospital. I don't blame this woman for wanting to greet her relatives as they came to Manzanar, but at the same time she broke a hospital rule. She might have spread measles to other people's children. Anyway, this woman has got no 'cabeza' (head).

The evacuee went on to describe the mess halls during the early days at Manzanar:

I had one helluva time trying to make my son eat. He just wouldn't touch anything or do anything except look around at the people. You see, we've never taken him to a cafeteria or restaurant regularly back home. The noise and confusion distracted his mind from the food. . . . Our family is not the only one which had trouble making children eat. It has happened in the majority of the families with small children. . . .

Sometimes we eat at home and my sons eat much better there than at the mess all. On the other hand, we (my wife and I) can eat in peace and need not hurry through our meals as we do when we eat at the mess hall. Yes, for the simple truth is that the mess hall workers don't like late and slow eaters as they want to hurry and get out of the kitchen as quickly as possible.

Regarding the dust and windstorms at Manzanar the evacuee observed:

I can readily sympathize with the Middle West 'dust-bowl' victims. We in Manzanar sure experienced what the 'dust bowl' victims underwent. Several times after I had washed and hung the clothes out to dry, a sudden wind would whip up and the ensuing dust storm would blacken the clothes. And worse yet, the sand and dust would get in the clothes and it was worse to wash them over than it was the first time. I felt like cursing. but what could I do but wash them over.

Concerning gossip among the evacuees at Manzanar and its impact on morale in the camp, the evacuee pointedly noted:

Japanese people are known to be gossips, especially women. Any little thing is subject for gossip. It is no wonder some people go batty from staying cooped up like this. [23]

Togoro Mizutani Family

In his aforementioned report prepared for the WCCA in April 1942 Milton Silverman reported that experiences of the Togoro Mizutani family that was evacuated from Los Angeles to Manzanar on April 2. He observed that it was "a typical Japanese group whose experiences mirrored those of many thousands of others throughout the early days of evacuation and relocation." In his report, Silverman included portions of interviews with family members, and he accompanied them during the first 24 hours they were in camp, recording their experiences and impressions.

In 1900 Togoro had emigrated from Japan to the United States, settling in the Fresno, California, area where he would work in vineyards and orchards for 20 years. With the aid of the Japanese consulate, Togoro brought Kaneo from Japan in 1917 to become his "picture bride." After the family, which had grown to include three children, spent a year in Japan in 1924, the Mizutanis returned to the Fresno area. In 1929, with the onset of the Great Depression, the family moved to Inglewood, near Los Angeles, where Togoro became a nurseryman. In 1940 the family moved to Sawtelle in West Los Angeles.

For three months after the Pearl Harbor attack, the Mizutanis "continued life almost without change." War affected them as it affected "every Japanese and non-Japanese family in West Los Angeles," but there were "few 'incidents' to tell the Mizutanis they were no longer part of the American people."

On March 18 Tatsumi, the Mizutani's 21-year-old son was fired from his job at a grocery store in Santa Monica. According to Silverman, Tatsumi stated:

All the Japanese were being fired all over town. Didn't seem to make any difference, aliens or citizens, we were all canned. So there I was — no job, no money. We heard about Manzanar, of course, and when I found out they were taking volunteers, and that there was work up there, well, volunteered.

Leaving his second-hand car at home, he drove with a friend in the automobile caravan to Manzanar on March 23. There was little work to do at Manzanar during his first few days at camp. Tatsumi stated:

Only a couple of the fellows got assignments. Nobody was being paid anything, but we wanted to work anyhow. If you didn't have something to do, you got thinking and worrying and losing your temper over the dust. We just loafed around all day, and watched the card games at night. Then I got a job as sanitary inspector — I know the fellow who's personnel manager here — and at least I could keep busy. Well, a little busy I looked at the mess halls, and checked the cooks and the waiters, and tried to get things cleaned up — nobody paid much attention, and some of those guys offered to swing on me — but I had something to do.

Finally, when it looked like it wasn't going to be too bad, I wrote to the family, told them what it was like, and asked them to come up as soon as they could.

Fusako, Tatsumi's younger sister who was studying business administration at the University of California, Los Angeles, informed Silverman that the family decided to volunteer to go to Manzanar after receiving her brother's letter. She observed:

We knew we'd have to go somewhere eventually, and my father and mother were getting pretty worried about somebody — well, doing something to us — and so we decided to move.

We'd been hearing about other Japanese being stabbed or killed up at Stockton, and we found out some Japanese had their trucks burned — with all their furniture on it. So this way, with the Army sort of protecting us and Tat already started up there, it looked like the best thing to do.

After volunteering to go to Manzanar, the Mizutanis had one week to sell their furniture. Fusako noted that many people in Los Angeles

would just go down the telephone book, call up every number under a Japanese name, and ask if they had anything to sell. Then they'd come over right away and look at it and make an offer. Most of the offers were really terrible, and if we wouldn't accept it, they would get insulting and tell us we were lucky to get anything. Some people were pretty nice, but most of them — ugh!

Most of the Mizutani furniture was less than a year old, but they received only "about one-third of what they expected.

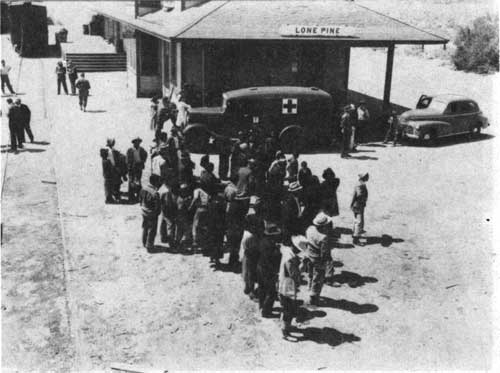

Thus, Togoro and Kaneo Mizutani and their daughter Fusako boarded the "special 'family' train" at Los Angeles on the morning of April 2. After a 10-hour trip, the train arrived at the Lone Pine railroad station. Silverman related:

There was no welcoming committee to greet them, just a half dozen townspeople and local reporters, drivers of the waiting busses that would take them to Manzanar, and the soldiers — a dozen military police armed with rifles and sub machine guns.

While the passengers in the train "packed the windows to stare at the towering, snow-covered mountains to the west, and while a nurse, a doctor and ambulance driver went through the train to find one baby with German measles," the "long process of unloading started." Helped down the car stairs by soldiers, the "evacuees came out of one car at a time, each carrying his own baggage roll and suitcase," "each stopping for a face-to-face meeting with the breathtaking mountains, and then on to the waiting busses." The busses headed north "up the highway to Manzanar, to the guarded entrance, over the dusty, rutted new road and up the street skirting the camp to the induction station."

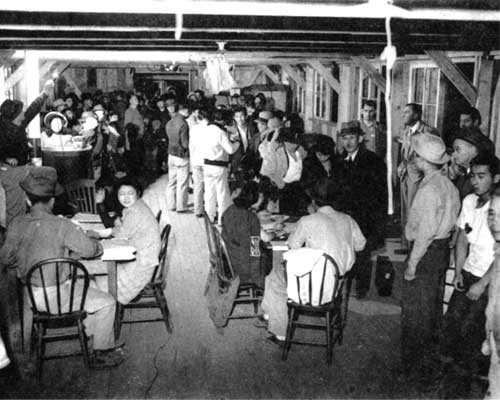

As the passengers disembarked from the busses at Manzanar, they were met by "a long line of earlier arrivals, a line leading into the building set aside for induction and registration." "Watching from an outer ring, and kept there by a few soldiers carrying bayoneted guns, were scores of others — men whose families hadn't shown up yet, men and women and children who had come in the day or the week before."

After standing in line for 20 minutes the Mizutanis reached the first desk inside the induction center, and "then — with Tat's capable assistance — they moved rapidly." A

Japanese girl registered the family on a card, listing their names and former address, taking the registration tag they had brought from Los Angeles (an FBI card, equipped with fingerprints and various information) and giving them instead new registration tag (without fingerprints), assigning them family quarters (Block 6, building 3, room 3), and sending them on to the second desk. Here a crew of Japanese boys counted noses, hauled three sets of brown army blankets from a huge stack, and dumped them on a counter.

Registration, at least for the time being, was completed. All the Mizutanis had to do was pick up three heavy loads of blankets, find their luggage which had been dumped somewhere outside, and then find block 6, building 3, room 3.

Tatsumi helped his family find their quarters, and several Japanese boys picked up the blankets and joined the procession. The group "slowly climbed the steep. dusty slope, jumping across little excavation ditches, walking boards across big ones, ploughing through mounds ot dust, passing building after building." The new Mizutani address was more than half a mile from the induction center.

Inside their new quarters, the Mizutanis sized up their future home. It was

a room 20 feet wide, 25 feet long, constructed of bare boards. There was no ceiling to cover the rafters. There were four sliding windows and one door. Inside were ten metal cots, a brand new Coleman oil heater, two light sockets and one light bulb in place.

As the Mizutanis looked at their quarters, Fusako looked at her brother in hopeless despair. Tatsumi told his family:

See, these ten beds — well, if there're only three in a family this kind of room is for two families. But if there are four or more — like us — we can have it all to ourselves. I'll get six of these beds taken out of here.

Tatsumi and the two other Japanese young men brought "puffy straw-filled tick" mattresses and placed them on the cots.

Then the Mizutanis went to dinner in a nearby mess hall. Served "in semi-cafeteria style," dinner consisted of "baked fish with tomatoes, white sauce, carrots, potatoes and sizzling hot coffee." On each table were "bowls of cole slaw and lettuce, bread, jelly, canned cream, sugar and a pitcher of Water with slight but unmistakable traces of Manzanar dust suspended on it."

After dinner, the elder Mizutanis returned to their room while Tatsumi and Fusako "with borrowed flashlight, went back to the induction building to find their luggage." The evacuees "were still coming in, lined up and waiting, old folks, women and children. They stayed patiently, even though the last ones — including mothers with babies in their arms, cold and tired, without food since the box lunches [on the train] at noon — waited until after 10 o'clock."

Among those still being processed were old family friends — the Charles Miyaji family from Venice. The children of Charles and his wife were daughter Tatsuko, a graduate of Santa Monica Junior College, and son Masanobu, a senior in chemical engineering at the University of California, Los Angeles. Both young people were volunteers who had come to Manzanar earlier and were working in the administration building. The young Mizutanis and the young Miyajis arranged for the two families to share the same quarters, and the Miyaji family moved into block 6, building 3, room 3. The problem of privacy was solved temporarily with "a rope and a blanket."

Besides being a sanitary inspector, Tatsumi was also a member of the camp entertainment committee. The night his family arrived at Manzanar, a camp dance was scheduled in the recreation building. The general idea, he said, was "to have a get-together between the Japanese from Los Angeles and the Japanese from Bainbridge Island." The social occasion, however, was largely a failure. Silverman noted that the

Bainbridge younger set did not attend. Only a few of the Los Angeles crowd appeared, for most were still helping the new arrivals get settled, but a dozen couples — with the inevitable stag line — came to the recreation building to dance to the special collection of phonograph records. It was jive, jive, and jive. Rhumbas, tangoes and even the Sweet waltzes were jeered off the program.

By order of the camp management, the dance ended at 10 o'clock. At 10:30 the Miyajis and the Mizutanis and most of the camp residents were in bed.

Soon after midnight, a "south wind" began howling, and the next morning the sun "came up through a dirty haze of dust." The Mizutanis awoke to a "grimy world." Dust and dirt were "on their beds, on the floor, in their hair, crunchy between their teeth The latrines closest to their quarters had not yet been connected with water pipes. Thus, they braved the wind and went to the south border of the camp "where a big water pipe (serving also as the official boundary) had been tapped every few blocks with faucets."

They washed the grime off their hands and faces, but "new dust was plastered on before they could dry themselves." Giving up, the family — "eyes squinted, handkerchiefs or hands over their mouths" — made their way to their mess hall.

According to Silverman, there were

no windows in the mess hall, only fine wire screens, but fortunately the screens were on the east and west sides of the building, and the south wind blew the dust clouds right past them. Breakfast — prunes, hash, coffee, jam and bread — brought a general upswing in spirits. Hundreds of family groups, eating together around the big tables, were gathered there; they were all wind-buffeted, all grimy, all hungry.

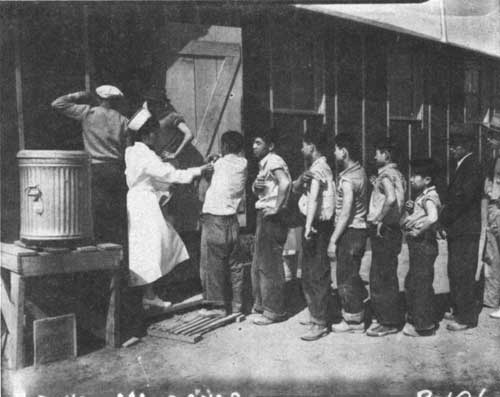

Young Japanese girls stood at the serving tables, passing out small bottles of milk to the children as they passed by, and offering fruit juice to mothers carrying small babies.

In his role as sanitary inspector, Tatsumi Mizutani observed that the dishwashers were dirty. The plates came "through their hands still covered with bits of grease and collected coatings of dust." They were "passed out in that condition, still half-wet, to late diners just getting into line."

After breakfast, the young Mizutanis walked to the new post office that had been established on April 1. For reasons of speed and efficiency, the Manzanar post office had been established as a branch of the Los Angeles post office, "making possible an oddity — a two-cent rate for a 223 mile trip, whereas a letter from Manzanar to Lone Pine, only 9 miles away, would cost three-cents." Two of the clerks at the post office were Japanese, both regular postal employees from Los Angeles and San Francisco "with civil service ratings, both "on leave." Officials had received requests to open a postal savings bank service, because many of the evacuees had "brought hundreds or even thousands of dollars in currency with them." Many others had defense stamps and bonds.

In back of the post office, the desert, according to Silverman, stretched off to the south — "miles and miles of mesquite and rabbit brush, some of it higher than a man." Off to one side were the new barracks being constructed for the military police. To the other, "marked by dense clouds of dust near the ground, were nearly a hundred Japanese workmen clearing out the desert brush with hoes, rakes and axes."

The young Mizutanis walked to the "temporary little hospital only a few buildings away" to receive their compulsory smallpox and typhoid vaccinations. Working in two teams, the four doctors and four nurses, all Japanese, administered the vaccinations under the guidance of Dr. James Goto, who had been a surgeon at the Los Angeles General Hospital prior to the evacuation.

Tatsumi and Fusako Mizutani next walked to the canteen stocked with soft drinks, candy, cigarettes, cigars, pipes, smoking tobacco, gum, stationery, soap, toiletries, baby foods, and "standard" medicines. While there, one army clerk reportedly exclaimed:

Everything will be O.K. if we can just keep up on pipes and cokes. . . . We've gone through dozens of pipes, and 120 cases of soft drinks in two days. Getting lots of special orders, too. The Japs want wash basins and boots and sweatshirts and especially dust goggles. We'll try to get 'em in town.

The young Mizutanis returned to their family quarters to find that their parents had "started to make a home out of the bare room." Wood picked up from the scrap pile "had become needed shelves." Nails were turned "into clothes hooks." A mirror "was fastened to the wall, surrounded by an array of brushes, combs, cosmetics and similar paraphernalia." On top of the oil stove were "a battered teapot and a package of tea."

According to Silverman, evacuees throughout the camp were making similar interior improvements. Few families had brought curtains, but many "prepared substitutes out of colorful dish towels." Woodworkers, "at least one amateur or professional in a family, turned out tables, stools, chairs, benches, shelves, necktie racks, cupboards, and 'geta' — simple 'shoes on stilts' each made from three pieces of wood and a few inches of cord, ideal for elevated transportation over dusty ground between room and showers."

Many windows, according to Silverman, had a decoration "slightly surprising to spot in an an evacuation camp for suspected aliens." These included "red, white and blue service flags with one, two or even three stars to signify sons serving in the United States Army" In many rooms were photographs of "a son in army uniform."

Other rooms, especially the men's barracks, indicated that "college freshmen lived there." Walls were plastered with "college pennants — California, Stanford, U.C.L.A., Southern California, Washington, Oregon and a dozen different junior colleges." There were "clipped pages from Esquire, sketches by Petty, photographs that would scandalize any American or Japanese mother, rooters' caps, football trophies, an examination paper with a heavily-circled A-plus, a few tattered textbooks brought along 'just in case,' new issues of Life, the sporting section of the Los Angeles Times." Outside, collegiate residents nailed placards to building walls with "titles of their own choosing — 'Penthouse #4,' 'The Island Club,' 'Pesthouse,' 'Love Nest,' 'Waldorf Astoria, Jr." Only a few of the signs were written in Japanese. Tatsumi told Silverman that while most "of our crowd can speak at least a little Japanese" few "can read or write it."

For lunch on their first full day at camp, the Mizutanis had chili, potatoes, turnips, salad, bread, pickles, and tea. The wind let up around noon, and the evacuees "began breathing again without benefit of handkerchief filters."

Tatsumi told Silverman that one of the most pressing problems facing Manzanar was what should be done with "the Japanese from Terminal Island." "They don't want to mix with the Los Angeles Japanese. And if we get some from San Francisco and San Diego and Sacramento, we're going to have still more trouble." Eventually "we'll have to realize there are a lot of 'grass widows' and 'temporary orphans' here — wives and children of men who've been picked up by the FBI and sent to concentration camps." If we have any trouble here, they will "probably be the ones to start it."

Even a "casual once-over at Manzanar, according to Silverman "revealed a startling absence of men between the ages of 20 and 50, a situation that emphasized the staggering number of children." Children were everywhere, playing in the streets and around the barracks, falling into excavations, and standing "along the big water pipe that ran down the southern boundary of the camp.

On the other side of the pipe line, workmen were "throwing houses into place" for the military police "with fascinating speed." Many of the workmen were friendly, bantering and joking with their audience. Some, however, "talked loudly in an accent which they fondly believed was "pidgin-Japanese." Other workmen — "many more than a small minority" — had "filthy, obscene barbs in their talk." They "hooted about the illegitimacy of the Japanese, they compared Japanese with various animals — to the advantage of the latter, they extended coarse invitations to the attractive Japanese girls, they dared the children to place their hands across the pipe-line boundary," hinting that the bayonet-armed military police would then cut their arms off.

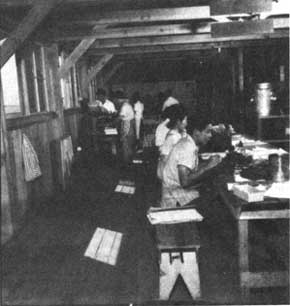

Although work had been promised to all evacuees who entered Manzanar, Silverman noted that jobs had been found for only 800 of the more than 2,000 evacuees in the camp. Most of these were part-time jobs, providing work for two or three hours a day At any one time, therefore, "more than 1500 were standing idle." As of April 3, less than "half a dozen" work projects using Japanese personnel had been started. Approximately "two dozen" young men and women were working as clerks, stenographers, typists and general assistants in the administration building. About the same number were serving in the "Japanese information center — i.e., complaint bureau — under the direction" of Dave Itami, a former Los Angeles newspaperman who had been educated in Japan and at UCLA and George Washington University. Several hundred were clearing nearby desert land, "doing work in hours that two tractors could have accomplished in minutes."A few hundred others were acting as messenger boys, porters, and general cleaner-uppers, working harder at finding work than at doing it." Other evacuees were cooks, waiters, and dishwashers, most of them occupied only three hours a day Some worked in the temporary hospital and the canteen. A "few score men had what came closest to full-time hard work — pruning the hundreds of old Manzanar apple trees."

Under the supervision of Ted Akahoshi, one of the few Japanese aliens given a responsible post at Manzanar, the pruning crews were "rapidly transforming the shabby old orchard into a semblance of its former glory" A graduate of Stanford University in 1913, Akahoshi had been manager of the Los Angeles Produce Merchants Association before the war. Tako Shima, a Los Angeles nurseryman who had spent four years working in apple orchards near Bakersfield, served as foreman of the pruning crews.

The young Mizutanis went to the administration building where Fusako applied for a job. The "major-domo" at the entrance of the building was Elbert Nagashima, a graduate of the University of Southern California in 1938 and, until several weeks before coming to Manzanar, a member of the maintenance staff at Paramount Studios. He passed Fusako to the personnel registration desk, where a crew of Japanese girls were interviewing applicants. There were many more applicants than jobs, but since Fusako listed shorthand, typing, and accounting among her skills, her registration blank was placed in a "special pile," and she was told she might get a job in "a week or two."

According to Silverman, farther back in the administration building — "not readily attainable by Japanese visitors" — were the offices of Clayton Triggs, the camp manager, and Ellis Pulliam, his first assistant. Together with the other administrative workers, many of whom were former WPA officials, Triggs and Pulliam were responsible "for everything that went on inside the boundaries of Manzanar. They were "swamped by every imaginable variety and degree of problem." In many cases, they had "pressing problems to solve but could find no answers." In others, they had the "answers ready, but were blocked by policy, lack of policy, precedent or lack of precedent — for example, the serious threat of delinquency coming from the lack of privacy in crowded barracks was uncovered by policy." Sometimes, the "apparently complete apathy or ignorance of supposedly cooperative agencies was to blame."

One problem facing Triggs and Pulliam was the disposition of the automobiles that the evacuees had driven to Manzanar. The cars were parked in an open field, and their distributor caps were removed and stored. As a result of the fierce dust storms, the cars' exterior finishes and engines were deteriorating. Pulliam thought that the vehicles could be used on the coast and had asked the Army "three times for somebody to come down and appraise the cars, and make a fair deal with the Japanese." Nothing had been done to date, and the dust kept "on wrecking them." [24]

Pulliam also voiced his concerns about the school situation to Silverman. He had contacted the state Board of Education, requesting that they start schools at Manzanar early to provide the children with something productive to do. However, the board insisted that it would not start schools at the camp until September, leaving many of the children with considerable idle time.