|

MANZANAR

Historic Resource Study/Special History Study |

|

CHAPTER EIGHT:

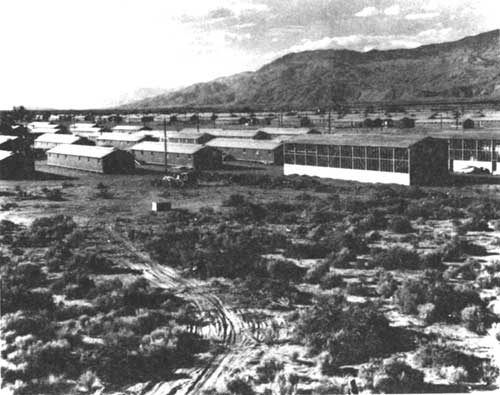

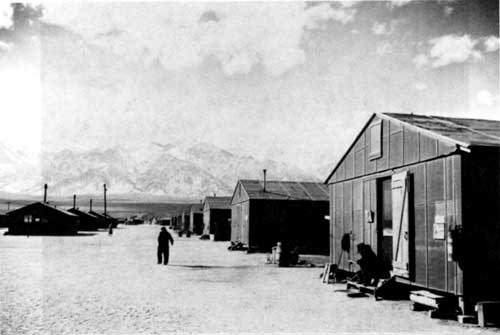

CONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE MANZANAR WAR RELOCATION CENTER — 1942-1945

As soon as the Manzanar site was selected, the Western Defense Command hurriedly began development of plans and specifications for construction of the camp. [1] Bids for the general contract to build the camp were opened by the U.S. District Engineer's Office in Los Angeles on March 5, approximately one week after the site for Manzanar was selected. The following day, Griffith and Company of Los Angeles received the general contract for construction of the temporary buildings and structures that would form the core of the camp at Manzanar, including installation of plumbing equipment and fuel oil lines.

During subsequent weeks, other contracts were let by the Corps of Engineers for construction of basic facilities at Manzanar, including water and sewage disposal systems, electrical, telephone, fire, and police signal systems, and buildings and structures (military police, administration, hospital, warehouses, industrial, oil storage, observation or watch towers, and fencing). Each of these contracts was supervised by the U.S. District Engineer's Office in Los Angeles. Funding for the construction was provided from the President's Emergency Fund. [2]

While construction of the Manzanar facilities was underway, the War Relocation Authority and the War Department reached an agreement on May 18, 1942, for administrative transfer of the camp from the WCCA to the WRA effective June 1. The construction program originally conceived by the WCCA and the WRA for relocation or reception centers was based on the requirements of Sections 5 and 7 of the Memorandum of Agreement that had been negotiated by the WRA and the War Department on April 17, 1942. Section 5 of the agreement stated that construction "of initial facilities at Relocation Centers (Reception Centers)" would be "accomplished by the War Department." The initial construction would include "all facilities necessary to provide the minimum essentials of living, viz., shelter, hospital, mess, sanitary facilities, administration building, housing for relocation staff, post office, store houses, essential refrigeration equipment, and military police housing." War Department construction would not include "refinements such as schools, churches and other community planning adjuncts." Section 7 of the agreement provided that after taking over existing reception centers, such as Manzanar, the WRA would operate them and "be prepared to accept successive increments of evacuees as construction " was "completed and supplies and equipment" were delivered. [3]

Thus, while Manzanar came under WRA administration on June 1, construction of the basic facilities at the camp continued under the Corps of Engineers in order "to meet minimum living requirements." After the basic facilities were completed, the WRA undertook various construction and remodeling projects at Manzanar within its Construction and Improvement Program, primarily using evacuee labor to conduct the work "under a force account system." The WRA construction projects included new buildings and structures, additions to existing structures, utility extension, remodeling, and refrigeration improvements.

Some the initial land improvements at Manzanar, including land clearing and development and construction of irrigation and drainage facilities, streets, roads, and bridges, were carried out by contract under the supervision of the Corps of Engineers. Most of these improvements, however, would be conducted later by the WRA using evacuee labor.

On June 8, 1942, about one week after the WRA assumed administration of Manzanar, Lieutenant General DeWitt and Colonel L. R. Groves of the Office of the Chief of Engineers agreed on "Standards and Details — Construction of Japanese Evacuee Reception Centers." [4] The standards were issued to provide "uniformity of construction" and "to obviate the necessity of miscellaneous correspondence in connection with construction of Reception Centers in Relocation Areas." The standards were to be followed "in all future construction and to the extent possible in current construction of Japanese Evacuee Reception Centers." This document, along with its several supplements, outlined the basic general facilities to be provided by the Corps of Engineers. Although many of the basic facilities at Manzanar were completed or in process of construction by the time that the standards were approved, they influenced the completion of the basic construction at Manzanar under the Corps of Engineers. [5]

Virtually all construction under the Corps of Engineers was conducted by contract. In some cases, delays in the delivery of building materials slowed construction projects. Because the Engineers' services were needed elsewhere, arrangements were made whereby WRA forces assumed responsibility for construction when the materials were finally received. Short and hurried time schedules, employment of inexperienced workmen, inclement weather, and use of lower grade materials all made "for a low standard of construction, which, it soon developed, raised many problems in connection with operation and maintenance." [6]

The Final Report, Manzanar contained an "Engineering Section" which detailed the "story of the construction of the Manzanar War Relocation Center, its maintenance, and operation from March 1942, to November 1945." The section was prepared by Arthur M. Sandridge, senior engineer at Manzanar from June 16, 1942 to February 15, 1946, and Oliver E. Sisler, Superintendent, Maintenance and Construction, from October 12, 1942 to February 15, 1946. The report divided the construction story of the camp into three sections: (1) the "basic construction" of camp facilities, including buildings and structures, water, sewage disposal, electrical, telephone, and fire/police signal systems, and initial land improvements, constructed under the supervision of the Corps of Engineers of the Los Angeles District; (2) WRA construction, including major new construction, utility extension, remodeling, and refrigeration improvements, performed under a force account system primarily using evacuee labor; and (3) land improvements, including clearing and development, irrigation and drainage, streets and roads, bridges, and fencing. Except where otherwise noted, this chapter will be based largely on the information found in the "Engineering Section" of the Final Report, Manzanar. [7]

"BASIC CONSTRUCTION" UNDER THE CORPS OF ENGINEERS

Buildings and Structures

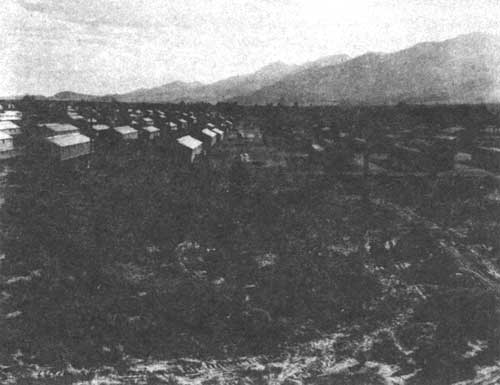

General Group. Griffith and Company of Los Angeles were the general contractors for all temporary buildings and structures, collectively referred to as the "general group," at Manzanar. This construction, which provided the housing and necessary support facilities for the evacuees, included the installation and furnishing of all plumbing equipment and fuel oil lines. Construction of the "general group" began in mid-March 1942, and Blocks 29-36, the last blocks to be completed, were opened to evacuees for occupancy during mid-June. The type size, use and number of buildings constructed as part of the "general group" were as follows:

| TYPE | SIZE IN FEET | USE | NUMBER |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barracks | 20 x 100 | Evacuee | 504 |

| Mess halls | 40 x 100 | Evacuee | 36 |

| Bath and latrines | 20 x 30 | Evacuee | 72 |

| Recreation halls | 20 x 100 | Evacuee | 36 |

| Ironing rooms | 20 x 28 | Evacuee | 36 |

| Laundries (cement floor) | 20 x 50 | Evacuee | 36 |

| Warehouses | 20 x 100 | Storage | 40 |

| Car garages (no floors) | 20 x 100 | Government cars | 2 |

| Truck garages (no floors) | 20 x 100 | Government trucks | 2 |

| Total | 764 [8] | ||

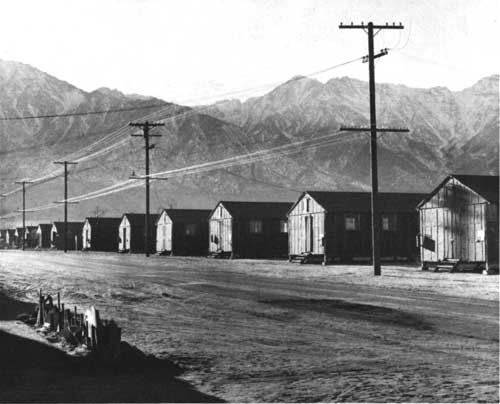

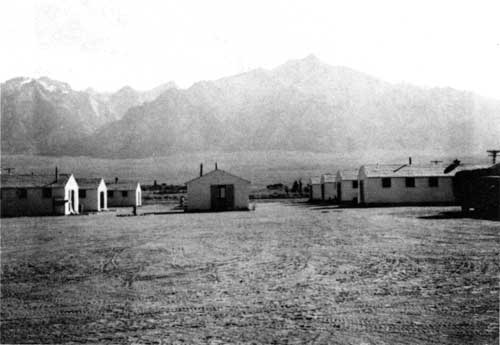

The buildings were grouped in uniform block arrangement. Each block consisted of 15 barracks and a mess hall in "exact 40-feet-apart locations." In addition, each block had two latrines (men and women), a laundry room (20 feet x 40 feet), and an ironing room between the rows. The men's latrine had eight flush toilets, while the women's had twelve. Each latrine had a shower room (12 feet x 12 feet) with an average of seven shower nozzles, and each laundry room had 12 laundry tubs for clothes washing "by hand, scrub board method." [9]

The temporary buildings and structures in the "general group" were "regular Army Theater of Operations (T.O.) type of construction, supported on precast concrete blocks, 14 in. x 14 in. x 8 in." The blocks were "placed on 10-feet centers down the sides and through the center." Girders were constructed of "2 in. x 6 in. material, spiked together to form 2 in. x 6 in. for the outside and 6 in. x 6 in. for the center span, supported 2 in. x 6 in. floor joist spaced 2 feet on centers." The floors were "1 in. x 6 in. tongue and groove or 1 in. x 6 in. shiplap." The walls "were framed from 2 in. x 6 in. material spaced 8 feet on centers." A "2 in. x 4 in. nailing girt, spaced half the distance between the top and bottom plates, furnished center nailing for the sheeting that was applied vertically." The rafters were "of 2 in. x 4 in. material spaced 48 inches on centers with a double 1 in. x 6 in. ceiling joist or cord, and 2 in. x 6 in. knee bracing on every other set or rafters." The roof was sheeted "with 1-inch random width sheeting and covered with 45-pound roll roofing." The walls and gables "were covered with 15-pound building paper, held in place by 3/8 in. x 2 in. lath or batts." The "barrack-type buildings were equipped with sliding 4-light sash windows, size 36 in. x 40 in., and 12 sash on each side." The warehouse group had "the same type window but was reduced to six windows to each side with a 5 ft. x 7 ft. double door in each end." [10]

Military Police Group. Griffith and Company constructed 12 buildings that comprised the "military police group" located south of the Manzanar evacuee camp area. Construction of the "Military Post was typical of the general group in the Center" with several exceptions. Thus, construction of these buildings was sometimes referred to as "modified mobilization type." The exterior walls were covered with "1 in. x 10 in. drop siding," and the "interior walls and ceilings were lined with 1/2-inch sheet rock." All exterior walls were painted as "a protection against the weather." The four barracks buildings were designed to house 200 men. The officers' quarters, designed to house 12 officers, included seven bedrooms, one lounge, and a toilet, while the guard house included a gun room and a "cage." The motor repair building, or garage, was an open shed designed for 8 trucks and automobiles. The recreation building was designed for a capacity of 60 persons, while the mess hall was designed to feed 120 men at one time. The type, size in feet, and number of buildings in the "military police group" included:

| TYPE | SIZE IN FEET | NUMBER |

|---|---|---|

| Barracks | 20 x 100 | 4 |

| Officers' quarters | 20 x 100 | 1 |

| Administration and store room | 20 x 100 | 1 |

| Recreation building | 20 x 100 | 1 |

| Mess hall | 20 x 100 | 1 |

| Guardhouse | 20 x 50 | 1 |

| First aid station | 20 x 28 | 1 |

| Bath and latrines (cement floors) | 20 x 30 | 1 |

| Motor repair building (cement floors) | 31 x 79 | 1 |

| Total | 12 [11] | |

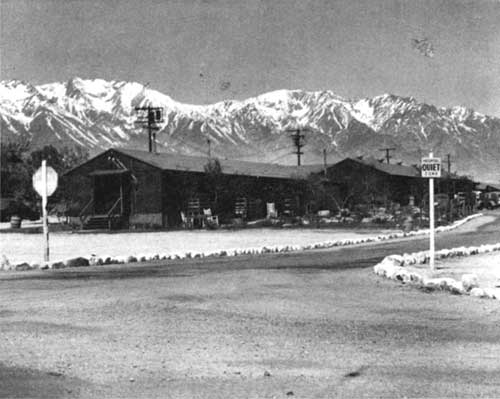

Administration Group. Twelve buildings, constructed south of Block 1 by Griffith and Company, constituted the "administration group." The administration building (labeled in the chart below as "Administration buildings,") was an "L"-shaped building constructed by placing together two pre-existing 20-foot x 100-foot structures. The interior of the structure had interior offices separated by partitions. This building, completed in late July or early August 1942, was located near the main entrance to Manzanar and was the principal administrative building for the camp.

The buildings in the "administrative group" were constructed similar to those in the "military police group" with two exceptions. The reception building, built to accommodate visitors to the camp who wished to meet evacuees, and the service station were "of the same construction as those in the general group." The type, size in feet, use, and number of buildings in the "administration group" included:

| TYPE | SIZE IN FEET | USE | NUMBER |

|---|---|---|---|

| Administration buildings | 40 x 100 | Offices | 2 |

| Administrative service station | 20 x 30 | Storage | 1 |

| Family apartment buildings | 20 x 100 | 4 apartments each | 2 |

| Men's dormitories | 20 x 300 | 6 apartments each | 2 |

| Women's dormitories | 20 x 100 | 6 apartments each | 2 |

| Provost building | 20 x 100 | Community government | 1 |

| Mess hall | 20 x 100 | Dining room | 1 |

| Reception building | 20 x 100 | Visitor reception | 1 (police station) |

| Total | 12 [12] | ||

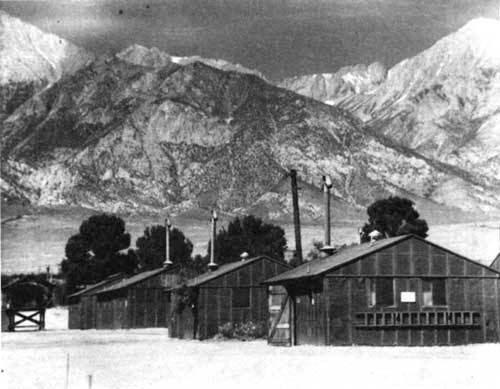

Hospital Group, Including Children's Village. When the first evacuees arrived at Manzanar, it did not have a permanent hospital facility. A temporary facility was established on March 21, 1942, in Block I, Building 2. "Apartment 2" was used for the hospital facility, and Apartment 3 served as a temporary ward containing five beds. On April 13 the hospital was moved into a barracks building partitioned into units containing ten beds each, as well as an operating room, pharmacy, laboratory, x-ray room, sterilizing room, utility room, linen room, record room, and kitchen. Four more barracks were eventually acquired for additional patients. [13]

On July 22, 1942, the Manzanar hospital moved into a permanent 250-bed facility (having 563,087 square feet of floor space) west of Blocks 29 and 34, and on September 12 a formal dedication ceremony was held. The "hospital group" included 19 buildings that were constructed by Griffith and Company. The administrative building was divided into offices, an out-patient clinic, an ear, nose, and throat clinic, a pharmacy, sterilizing room, laboratory, and facilities for x-ray, minor surgery, and surgery. [14]

The hospital buildings were of "the same type of construction as the general group with the exception of the heating plant." This building was "wood frame construction with the walls and roof covered with galvanized corrugated iron." All other buildings within the "hospital group" were "spaced a minimum of 50 feet apart and connected with covered walks" and were "of wood-frame construction with wood floors covered with linoleum." The covered walks were "8 ft. 3 in. from the finished floor to the top of the plate line, with an overall width of 6 ft. 7 in."

The walks connecting the hospital administration building with the wards, mess hall, and morgue "were closed on the sides with double-hung windows spaced, approximately, 9 feet on centers." The "walks connecting the nurses' and doctors' quarters to the ward walks were open on the sides with a hand rail extending the full length of each walk."

The heating system consisted of three "Kewanee 60-H.P. oil-fired steam boilers, equipped with Johnston automatic oil burners, and all necessary piping valves, pumps, and radiators for complete and adequate heating of ail buildings, and for washing and sterilizing in all wards, operating rooms, offices, clinics, and laundry." The Children's Village (orphanage) buildings were in a separate building group, and each building was heated "by oil-burning space heaters." The hot water system for the hospital group consisted of "one 60-gallon H.C. Little automatic hot-water heater for each building." [15]

The Children's Village was an orphanage for evacuated Japanese children located in the firebreak south of Block 29. One of the buildings was a girls dormitory, one a boys dormitory, and a third contained a mess hall, administrative offices, and staff housing. As the three buildings comprising the Children's Village were nearing completion in mid-June 1942, it was reported that these structures were "larger than the standard barracks, having porches at each end." Compared with the evacuee barracks, the village buildings were "superior in construction, having double flooring, double walls, ceiling, double partitions, inside showers and toilet facilities." [16]

The type, size in feet, capacity, and number of buildings in the "hospital group" included:

| TYPE | SIZE IN FEET | CAPACITY | NUMBER |

|---|---|---|---|

| Administration | 255 x 147" | 1 | |

| Obstetrical ward | 25 x 150-1/2 | 35 beds | 1 |

| General wards | 25 x 150-1/2 | 37 beds each | 4 |

| Isolation wards | 25 x 150-1/2 | 2 | |

| Mess hall | 40 x 60 | 1 | |

| Doctors' quarters | 20 x 100 | 5 doctors | 1 |

| Nurses' quarters | 20 x 100 | 23 nurses | 1 |

| Hospital laundry | 20 x 100 | 1 | |

| Hospital morgue | 23 x 33-1/2 | 1 | |

| Heating plant | 40 x 38 | 1 | |

| Warehouses | 20 x 100 | 2 | |

| Children's village | 25 x 150 | 33 beds each | 3 |

| Total | 19 [17] | ||

Miscellaneous Group.

Refrigerator Warehouses — Two refrigerator warehouses were constructed under a contract sublet by Griffith and Company to Hugh Robinson and Sons of Los Angeles in the warehouse area south of Block 2 and west of the "administrative group" area in July 1942. The two structures "had an overall size of 20 ft. x 100 ft. with approximately 7 ft. 6 in. ceilings." The refrigerator rooms "proper were 20 ft. x 80 ft. with 7-ft. ceilings, and were insulated with 6 inches of Palco-wool on the sides, ceilings, and floors." The doors at each end were "3 ft. 6 in. x 6 ft. 6 in." and had "4 inches of Palco-wool for insulation." The interiors of the rooms were sealed with "1-inch tongue-and-groove ceilings." The exterior finish was "1-inch sheeting covered with 15-pound building paper and 3/8 in. x 2 in. batts to hold the paper in place." A 20-foot x 40-foot annex (sometimes referred to as the "reefer house"), connecting the two structures, "was used for meat cutting and the sorting of fruits and vegetables."

Each warehouse had "four evaporator condensers, recold humid-air type." Operating on defrost they "maintained a 34-degree to 36-degree temperature in the meat refrigerator, and 38- to 40-degree temperature in the vegetable refrigerator."

The compressor and condensing units were housed "in a 10 ft. x 10 ft. room, an integral part of the refrigerator rooms." The compressors were "Brunner, model E, Type C, driven by a 7 1/2-H.P. 220-volt, 3-phase Fairbanks Morse electric motors." Drayer Hanson condensing units, "model 11/4-inch, L-3, 1/4-H.P.," were used on both units. [18]

Net Garnishing or Camouflage Buildings — Five buildings were constructed at Manzanar by the Q.R.S. Neon Corporation of Los Angeles for "garnishing or camouflaging" nets for Army use. Three of these buildings were of uniform size and construction: 300 feet x 24 feet with an overall height of 18 feet from the finished floor to the plate line. Two buildings had additions that served as offices: 12 feet x 20 feet with shed roofs.

The camouflage buildings exhibited "heavy construction" techniques. Posts "measuring 6 in. x 12 in. on 10-foot centers supported a double set of 2 in. x 6 in. rafters bolted to each side of the post." The rafters were "tied together with a 2 in. x 6 in. cord and 2 in. x 6 in. knee braces, extending from approximately 2 feet below the plate line forming a modified form of scissors truss." Intermediate "2 in. x 6 in. rafters with 2 in. x 6 in. cords and spaced 2 feet on centers completed the roof framing." The roof "was covered with 1-inch random-width sheeting laid diagonally and covered with 90-pound roll roofing."

The walls were constructed with "two horizontal 2 in. x 6 in. nailing girts and 2 in. x 6 in. verticals spaced on 2-foot centers." The sides were "covered with 10-inch drop siding from the floor to 10 feet above." The ends were "covered from the floor to the ridge." The walls were braced "with 2 in. x 6 in. bracing." Cement floors were constructed throughout the buildings.

Another building in this group, typical in construction detail except for size, was "24 ft. x 100 ft. with an adjoining open shed for storage 60 ft. x 100 ft." This shed had "8-foot walls open on one side, and covered on one side and one end with "10-inch drop siding." "Two-by-six rafters, spaced on 4-foot centers were sheeted with 1-inch random-width sheeting and roofed with roll roofing." A wood floor "of 1 in. x 6 in. sheeting" was constructed in this addition.

A fifth structure in the camouflage buildings group was a cutting shed, "150 ft. x 24 ft. 6 in." All the materials necessary for the fabrication of the nets were processed in this building. It was constructed of "2 in. x 4 in. floor joists with 1 in. x 6 in. shiplap flooring, 2 in. x 6 in. studding 8 feet long, spaced on 4-foot centers, 2 in. x 6 in. knee braces with every forth [sic] set of rafters." The rafters were "2 in. x 6 in., spaced 3 ft. 4 in. on centers." One side was left open while the other side was sheeted from the floor to the plate line with 10-inch drop siding." Both ends "were sheeted from the floor to the ridge with the same material." [19]

Oil-Storage Tanks and Platforms — Griffith and Company constructed 37 oil-storage tanks and platforms — one in each block of evacuee barracks and one at the military post. The structures were built for the storage of fuel oil for distribution through pipe lines to the hot-water heaters (and later the ranges) in the mess halls, to the hot-water boilers in the boiler rooms attached to the latrines, and to the boiler in the rooms attached to the laundries. Fuel oil was also stored in the tanks for daily distribution to the evacuees for use in the spare heaters in their barracks.

The storage-tank platforms rested on "12-in. x 12-in. concrete piers projecting approximately 12 inches above the natural grade, and of sufficient depth to insure a solid footing." Four posts, "6 in. x 6 in. x 5 ft., spaced 7 feet on centers with a 6 in. x 6 in. cap projecting 2 feet beyond the posts, formed the bents for a deck or floor of 3 in. x 10 in. x 12 ft. Douglas fir." A gable roof, covered with roll roofing, covered the platforms. The roofs were "open on the gables" and were "supported by 2 posts, 4 in. x 4 in. x 5 ft., at each corner with 3 intermediate studs of 2 in. x 4 in. material." Plates, "2 in. x 4 in.," and ties were used for support and for bracing the roof. The "under-structure" was braced "horizontally and diagonally with 2 in. x 6 in. material."

Twelve of the cylindrical galvanized iron tanks had a capacity of 2,450 gallons, while 25 of the tanks had a capacity of 1,250 gallons. Two 6,000-gallon reinforced concrete tanks at the hospital boiler house were used for fuel storage for the hospital. These tanks were buried below grade. [20]

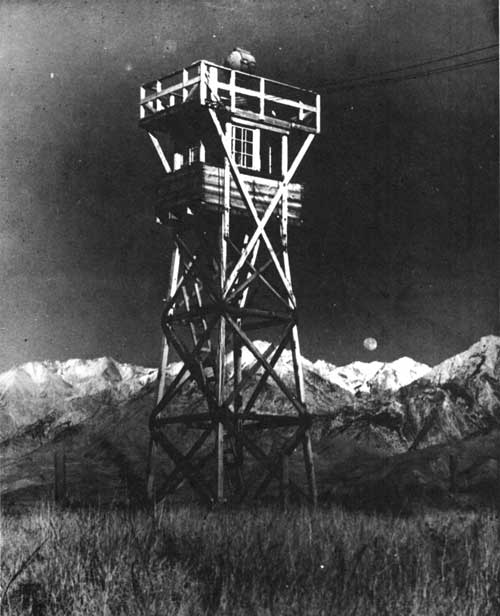

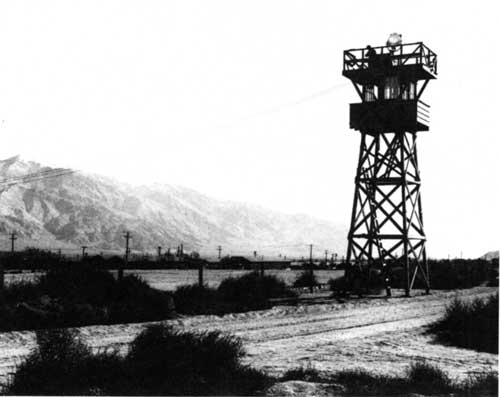

Observation or Watch Towers — According to the Final Report, Manzanar eight wood observation or watch towers were constructed on the perimeter of the camp by Charles I. Summer, a contractor in Lone Pine. The eight watch towers, however, were not all built at the same time. After War Relocation Authority officials visited Manzanar on May 7, 1942, as negotiations were underway for transfer of the center from the WCCA to the WRA, John H. Provinse, chief of the WRA Community Services Section, reported to Milton Eisenhower that it was proposed

to install during the coming week 8 observation and guard towers on the project in order to facilitate the military patrol work. Inasmuch as our direction of effort should be away from surveillance of these people as enemies or as anything else than participant American citizens, it seems extremely undesirable to establish such guard towers. Mr. Fryer [who accompanied Provinse] said that he would do everything he could to prevent their erection. In case they are erected while the project is still in Army control, they could be removed after the War Relocation Authority takes over, or they could be allowed to remain without being used. The military contingent at the present time consists of one company of 99 men and patrols are established around the external confines of the project. . . . [21]

Despite WRA opposition, however, four watchtowers were constructed on the perimeter of the center by late July 1942. On July 31, Manzanar Director Roy Nash observed:

.... Four towers with flood lights overlook the Center; the Relocation area is the whole 6,000 tract of which the Center is but a part.

.... There is a company of Military Police stationed just south of the Center, whose function it is to maintain a patrol about the entire area during the day; and to man the towers and patrol the Center at night. A telephone is being installed in each tower so that if a fire breaks out, it can immediately be reported. The whole camp is under the eyes of those sentries. . . . [22]

During August 31 to September 2, 1942, P. J. Webster, Chief, Lands Division, for the WRA in San Francisco conducted an investigation of Manzanar, focusing on claims of lax security at the relocation center. Among other observations he reported to his superiors on September 7:

I asked Captain Archer and Lt. Buckner of the Military Police whether they thought it was possible for the Japanese to leave the Relocation Center and fish or swim. They said they had heard that the Japanese were doing some fishing and swimming west of the Center, but if this were true they were doing it at a very great risk to their personal safety. They said that there were about 120 soldiers in their unit, and that this made it difficult to post an adequate guard on the west side, twenty-four hours a day. At the present time there are 11 guard posts being maintained on a 24 hour basis. . . . I inspected the guarding service along the west line, which is approximately 7/10 of a mile in length. This area is patrolled, but so lightly that a person could go over the line without being noticed. This is particularly true because there is a trash-burning dump a little distance from the west boundary of the Center. In connection with this dump, a long trench has been excavated and the dirt therefrom forms a long barrier about five feet high. If a person gets over this barrier he can proceed a considerable distance to the west, out of sight of anyone patrolling the west boundary. Furthermore, at night there are no search lights along the west boundary. . . .

Another statement which Lt. Buckner made emphasizes the attitude of the Military Police and also that they take the patrol service with the utmost seriousness. He said that he, personally, would not be willing to attempt to cross through the beam of light thrown by one of the four search lights now installed for a thousand dollars, even though he had on his soldier's uniform. . . .

Realizing that the patrolling of the west side was not satisfactory, Captain Archer, over a considerable period of time, has been trying to get additional watch towers and search lights. His request has just been approved and plans are now under way for the installation of four more towers, which will make a total of eight. When this installation is completed there will be a tower at each corner, and at the middle point of each of the four sides of the Center. Twelve powerful search lights will be installed which will throw a broad beam of bright light around the entire Center. When this is completed it appears very unlikely that any Japanese will leave the Center without permits during hours of darkness. [23]

On August 11, 1942, Lieutenant Colonel Claude B. Washburn of the WCCA inspected the security arrangements at Manzanar. He reported that three guard towers were "needed in back" [west side] of the center. "Guards in [the] rear walk[ed] through brush" and were "unable to see much of their area." "One man alone" had "no protection against attack." [24]

The last four observation or watch towers at Manzanar were completed by early November 1942. An inspection report by WRA and military officials on November 5-7, 1942, noted that there "Should be 8 [watch or observation towers] at this center." The eight towers in use were "weatherproofed." Searchlights on four of the towers (Nos. 1-4) were wired, while those on four (Nos. 5-8) were not wired. [25]

The towers, as completed by Summer, were supported on "24 in. x 24 in. concrete piers embedded in the ground a sufficient depth to insure a sound footing" to "take care of the weight and wind load." Each pier had anchor straps to secure the "6 in. x 6 in. corner posts." The towers were "8 feet square at the base and 6 feet square at the top." The corner posts, "6 in. x 6 in., were of Douglas fir." Each tower had two platforms. The lower one (30 feet high), "6 ft. x 10 ft., was enclosed with 2 in. x 6 in. joists and 2 in. x 6 in. flooring with 1 in. x 8 in. shiplap and two sash windows, 2 ft. x 3 ft 6 in., were installed on each side. " The upper platform (40 feet high) was "8 ft. x 12 ft. with 2 in. x 8 in. girders, 2 in. x 6 in. joists, and 2 in. x 6 in. flooring." A railing of "2 in. x 4 in., with 2 in. x 4 in., posts encircled this platform." The towers were "securely braced, both horizontally and diagonally." A "2,000 candle power searchlight was mounted on each tower." [26]

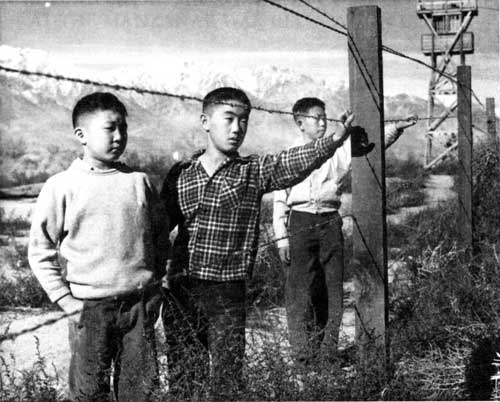

Fencing — Installation of the fencing at Manzanar is not well documented, and many of the documents appear to provide conflicting information. On July 31, 1942, Roy Nash, director of Manzanar, stated:

The Relocation Center is that district, approximately a mile square, in which all the buildings of Manzanar are located. It is fenced with an ordinary three-strand barbed-wire fence across the front [east side along the highway] and far enough back [west] from the road on either side to control all automobile traffic. Four towers with flood lights overlook the Center; the Relocation area is the whole 6,000 tract of which the Center is but a part. [27]

The aforementioned inspection of Manzanar conducted on November 5-7, 1942, by WRA and military personnel contained minimal information on fencing. The inspection report stated:

Under contract - 1 side and 1 end completed - balance in 1 week. Net garnish area - completly (sic) enclosed - including timekeeper's shelter and entrance gates. [28]

In connection with the inspection, the Corps of Engineers prepared a "Transfer of New Construction" form dated November 5, 1942. This document stated that a five-foot-high, five-strand, two-point barbed wire fence, mounted on wood posts, which would eventually run for 19, 388 linear feet around the camp, was only half complete. [29]

The Final Report, Manzanar notes that the C. J. Paradise Company, a contracting in Los Angeles, removed "5,000 lineal feet of old fencing" from the Manzanar site and installed "18,871 lineal feet of new fence of 5-strand barbed wire around the boundaries of the Center area [evacuee residential area]." This fence "was contracted for through the U.S. Engineers." [30]

The aforementioned "Fixed Asset Inventory" listed three fencing categories at Manzanar that "were acquired" from the WCCA "at the time that the War Relocation Authority took possession of the lands from the War Department." [31] The categories, as listed in the aforementioned "Appraisal Report," were:

1. Boundary Fence, camp area boundary lines, 5 strands of double barbed wire, 19,380 feet

2. Fence, motor pool area, 5 strands of double barbed wire, 1,020 feet

3. Fence, camouflage building area, 5 strands of double barbed wire, 715 feet [32]

The aforementioned "Explanatory Notes" attached to the "Appraisal Report" provide additional information on the fencing at Manzanar. The "Notes" state that the "boundary fence of the main portion of the camp is built of 5 strands of medium heavy barbed wire on sawed fir posts." The fences around the motor pool and camouflage building areas had "a good many rough posts made of locust wood which, although smaller than the sawed posts, is more durable." Some of these latter fences had "7 or 8 wires - a few only 4 wires," but the "average of each enclosure" was selected "as the best method of appraising the value." The number of posts for each category of fencing was: boundary fence, 1,174 posts; motor pool area, 61 posts; camouflage building area, 44 posts. [33]

Water and Sewage Disposal Systems

Water. Initially, the water supply for the Manzanar camp was provided on a temporary basis by a water tank located west of Block 24. The tank, which had a capacity of 98,000 gallons, was emptied an average of 15 times each 24-hour period. Because of the inadequacies of this system, construction was begun on a new concrete basin reservoir located northwest of the camp along Shepherd Creek on May 22, 1942. [34]

The permanent water supply system for Manzanar, which was completed in July 1942, was constructed under contract by Vinson and Pringle, a construction firm in Los Angeles. The system consisted of a concrete dam and settling basin on Shepherd Creek, "approximately 3,250 feet north and west of the Center in T 14 S, R 35 E, Sec. 9." Water was carried through an open cement-lined flume from the settling basin to the storage reservoir. Water passed through a chlorinator on the way to the reservoir. The reservoir, "120 ft. x 180 ft. with a capacity of 540,000 gallons," was constructed "with 45-degree earth embankments reinforced with wire mesh and lined with concrete." Two "14-inch calico gates regulated the water within the reservoir." One gate "emptied into a control spillway and the other emptied into a 14-inch supply line."

Water was carried from the reservoir through "4,650 feet of 14-inch welded steel pipe into a 90,000 gallon steel storage tank." An "8 ft. x 22 ft. chlorinator house of temporary frame construction" was built adjacent to the storage tank for the housing of a "H. T. H. chlorinator machine, Clayton valve, sand traps, meters, and a 6-inch by-pass line." The water line from the reservoir to the storage tank was laid "in the open ditch that carried the temporary water supply into the camp area." This line was insulated by "covering it with an earth fill." Drainage facilities were provided by the "installation of hexagonal wooden culverts placed below the level of the pipe line."

The pipe line and the steel storage tank were constructed by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. The pipe line was insulated and the wooden drainage culverts were installed by the C. J. Paradise Company of Los Angeles.

A 12-inch distribution main of welded steel pipe, equipped with 12-inch Sparling meter having a capacity of 2,000 gallons of water per minute, carried water from the storage tank to branch mains throughout the center. The water distribution main system consisted of 5,170 feet of 12-inch, 6,340 feet of 10-inch, 8,822 feet of 8-inch, 29,745 feet of 6-inch cast-iron pipe and 706 feet of galvanized steel pipe. All service lines were "of galvanized iron pipe ranging in size from 3/4-inch to 2 1/2 inches," A total of "40,266 lineal feet of pipe" was used for the system.

An emergency standby system was installed to supplement the water supply "during freezing weather and in the event of a bad fire, which would necessitate the use of more than the normal amount of water supplied by Shepherd Creek." The standby system was installed at well 75 and consisted "of one 10,000-gallon redwood storage tank, and two 4-inch 50 horse power motor driven Fairbanks Morse booster pumps." Water was pumped through a master meter into the storage tank "by the City of Los Angeles pump with a 75 horse power electric motor." The water was pumped from the tank into the mains by the Fairbanks Morse booster pumps. To facilitate the control of water within the center, "34 6-inch, 20 8-inch, 15 10-inch and 8 12-inch gate valves" were installed throughout the water system.

At the time of its completion, the water system provided a daily supply of 1,500,000 gallons of water from Shepherd Creek to the camp. The remainder of the creek's flow went to the Owens River.

Fire protection was provided by the installation of 84 fire hydrants in the center. Additional protection was afforded the hospital by installation of an automatic sprinkler system, consisting of 522 sprinkler heads, placed in seven ward buildings, the hospital mess, and the covered walks. A 3-inch pipe was used in the covered walks, while a 1-inch pipe was used in the wards and mess hall. [35]

Sewage Disposal. The sewage disposal system at Manzanar, consisting of a collection and outfall system and a sewage treatment plant, was constructed by Vinson and Pringle of Los Angeles. Considered to be one of the most modern sewer systems of its time in California, the system cost some $150,000 to construct. [36]

The sewage treatment plant was located approximately 1,000 feet east of the evacuee residential area in T 14 S, R 35 E, SW 1/4 of Sec. 12. Construction of the system was commenced in April 1942, but it was not completed until mid-summer. During the construction period, a temporary septic tank "100 ft. x 20 ft. x 6 ft.," was used, with excess waste being "allowed to run over the desert waste land." All sewage entering this tank was treated with chlorine. [37]

The collection system within the center "consisted of 2,500 lineal feet of 18-inch, 1,100 lineal feet of 15-inch, and 26,502 lineal feet of 8-inch vitrified clay pipe." A siphon was constructed to carry the outfall line under the Los Angeles Aqueduct. This siphon consisted of two 12-inch cast-iron pipes encased in concrete.

After leaving the outfall sewage line, the raw sewage entered the treatment plant which was located on one acre of land and had a designed capacity of 1,250,000 gallons per day. The plant consisted of seven units: (1) grit chamber; (2) scum and distribution box; (3) clarifier; (4) control house; (5) digester; (6) chlorine contact tank; and (7) sludge beds. Each unit with the exception of the control house and sludge beds was constructed with concrete. At the plant liquid and solid wastes were separated and treated. Any gas extracted went into boilers to be used for heating, while solid wastes passed through a chlorinator and into sludge pits where evaporation converted them into a substance used for fertilizer. [38]

At the treatment plant sewage first passed through the grit chamber which was equipped with bar screens. Then it entered the parshall flume where the metering and extension of the chlorination system occurred. The sewage left this unit to enter the distribution box, consisting of two calico gates.

The clarifier unit was a tank constructed of concrete, 60 feet in diameter and 9 feet in depth. The tank, with a rate of flow that varied from 500 to 1,750 gallons per minute, was equipped with a mechanism to process the sewage.

The control house, a "32 ft. x 58 ft. frame building with concrete floors, rustic siding and roll roofing," contained an office, laboratory metering gauges, and chlorinator control equipment. Manual and automatic control chlorinators were used, each having a maximum capacity of 200 pounds of chlorine per unit for each 24 hours. Each tank was equipped with a meter to register the flow of chlorine within its working range.

The sludge and scum pumps were housed in a concrete pit, "16 ft. x 14 ft. x 5 ft., with a frame roof covered with roll roofing to protect them from the weather."

The sludge digester was the "2-stage type, 40 feet in diameter with 22 feet 6 inches overall water depth." The water depth "in the upper compartment was 12 feet 3 inches and the lower compartment was 10 feet." The digester was arranged "with a horizontal concrete tray separating the lower and upper compartments which were operated in series." Intensive mixing was provided "in the upper compartment followed by quiescent settling in the lower compartment." The two compartments were connected by exterior piping.

The chlorine contact tank was made of reinforced concrete with reinforced concrete baffle walls. The dimensions of the tank were "8 ft. x 16 ft. 6 in. x 38 ft.," and it was "equipped with three standard manhole frames and covers." A "6-inch cast-iron pipe to the scum pump line removed any collection of material in the bottom of the tank." An l8-inch cast-iron influent pipe "served the contact tank from the clarifier." The chlorinated sewage was removed to the drainage area through an 18-inch vitrified clay pipe.

Four sludge drying beds, 50 feet x 100 feet, were constructed. The ground surface was leveled, and dikes or berms 31/2 feet high were constructed. Six inches of sand was placed in each bed. The sludge was carried to these beds through a 6-inch cast-iron pipeline. [39]

Electrical, Telephone, and Fire/Police Signal Systems

Electrical System. Electrical power was supplied to Manzanar by the Los Angeles City Bureau of Power and Light from its power station on nearby Cottonwood Creek. The system consisted of 58,400 lineal feet of overhead distribution lines that provided service to 730 buildings. A master switch controlled the entire camp, and a master meter registered all electricity used within the camp. In addition to lighting the buildings, 190 alley and street lights were served. To service the camp, 79 transformers were installed, ranging in size from 2 kVA to 37 1/2 kVA. [40]

Telephone System. The telephone system was installed by the Interstate Telegraph Company. Telephone wires were strung across arms that were installed on existing power poles. The system included a 40-line switch. To complete the project seven miles of "3-circuit #9 wire" and seven miles of "2-circuit #12 N.B.S. copper wire" were installed. [41]

Fire/Police Signal System. A signal system adequate to meet the needs of both the "Fire Protection and Internal Security" sections was installed by the Interstate Telegraph Company under contract with the U.S. Signal Corps. Outside installation included cross arms and "approximately 1,500 feet of lead covered cable and 20,700 lineal feet of 2-wire telephone line." "Inside plant and station equipment" included installation of an additional strip of ten jacks in the existing switchboard and "21 telephone instruments, drops, protectors, and appurtenances." [42]

Land Improvements

Initial land improvements at Manzanar were carried out under contract by the C. J. Paradise Company of Los Angeles. Streets, alleys, and building sites were graded and given a light coat of penetrating oil to permit passage of motor vehicle traffic and enable construction operations to proceed. "No primary grading of the streets or drainage structures," however, was conducted by this firm. [43]

STATUS OF CONSTRUCTION AT MANZANAR WHEN THE WAR RELOCATION AUTHORITY ASSUMED ADMINISTRATION ON JUNE 1, 1942

When the War Relocation Authority assumed administration of Manzanar on June 1, 1942, George H. Dean, a Senior Information Specialist in the WRA's office in San Francisco, undertook assessment of conditions at the relocation center. After his inspection, he issued a lengthy report describing both the administrative operation and the physical conditions of the camp which then housed 9,671 evacuees. Among his observations on the physical conditions and status of construction at Manzanar were the following:

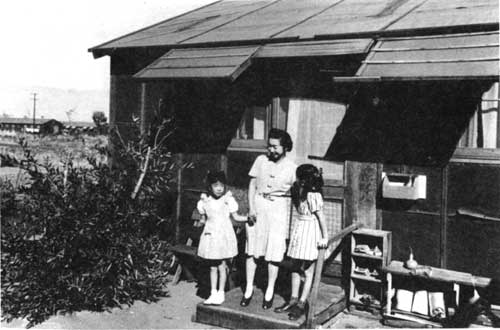

The War Relocation Authority, in acquiring the Manzanar project, took over a plant consisting of 724 wooden barracks buildings, a hospital group and a children's center. . . .

In many instances, especially on those days when heavy arrivals of evacuees occurred, assignments to the barracks have been made perhaps inevitably in an indiscriminate manner, resulting in serious overcrowding in some of the buildings. Many cases existed of eight and ten persons of various ages being housed in a single apartment, sometimes two and three separate family units. This has resulted in a health and sanitation problem, and in some scattered instances in an unsatisfactory moral situation.

Floors and walls of the barracks reflected considerable deterioration, large cracks developing from the drying out of the lumber under the heat and low humidity in this area. They were, and are, rough and difficult to keep clean, and on some days as high as nine complaints have been received at the engineering office on floors giving way. Linoleum and felt padding had been ordered for installation in all barracks and mess halls, and the installation in the messes had been completed on June 1. The remainder of the work of laying the linoleum in the barracks will be performed by Japanese labor, but this had to be postponed as white union labor would not work on the project simultaneously with Japanese labor.

Barracks were turned over to the evacuees without steps and it has been necessary to construct 2,232 sets of steps on which work was about 75 percent complete when lumber supplies were shut off. Considerable difficulty has developed from plumbing valves sticking. Because of the peculiar type of valve used, it is hard to replace them. On the whole, however, the amount of plumbing disorder is not abnormal for a community of this size.

Electrical installations and overloading of the lines because of the large usage of electrical devices, such as irons, heaters and radios, by the evacuees have created a serious fire hazard in all of the barracks. Wiring is openly strung in the buildings. The evacuees have more than five and a half miles of electrical cord connected to electrical accessories. Most of this cord is in good condition at the present time, but with continual overloading of the wires it will deteriorate abnormally quickly. Numerous daily blowing of fuses is evidence of the overloading. . . .

The water supply is not entirely completed. . . . Tests conducted in May revealed a rather high degree of pollution and a trace of E. coli. There has been a comparatively high incidence of dysentery within the project and studies were being made to determine whether this was attributable to pollution of the water supply. . . .

Dishwashing equipment was inadequate and unsanitary. Additional equipment had been ordered prior to June 1 and is in the process of installation. Dr. Harrison, chief of the 5th Public Health District, described the dishwashing situation as the most serious health menace in the project. The supply of hot water, both in the kitchens and wash rooms is adequate under normal usage but is insufficient to meet peak loads.

Sewage from the project is siphoned under the aqueduct east of the camp and spread out over the open land. A disposal plant was commenced by the army prior to June 1 and is under construction. Sectional drainage problems exist and water collects under some of the barracks. Garbage collection generally is handled satisfactorily. It is dumped in an open pit east of the project, burned and buried. No attempt is made to use the wet garbage but plans were being drawn for hog and chicken projects to utilize this waste. . . .

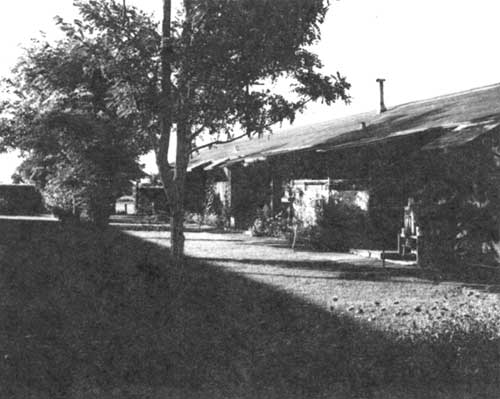

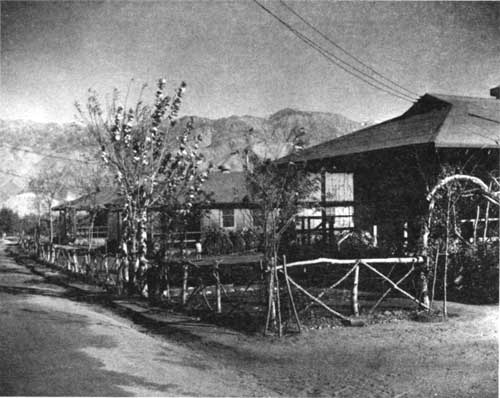

On June 1, no provision had been made for buildings to house the carpenter shop, repair shops, plumbing shops, equipment sheds, or a lumber yard. The shops are being temporarily housed in warehouse buildings. . . . No landscaping work had been done prior to June 1, except for a limited, voluntary improvised project in front of the guayule experiment and plant propagation stations. The absence of landscaping was due to the lack of both equipment and stock. In this respect, the project was substantially as it was when the land first was cleared of the native sagebrush growth. Neither had steps been taken looking towards dust palliation. The project possessed no sprinkler wagon and a limited amount of hosing was done by hand. With the destruction of the natural ground cover, the dust problem is acute on windy days. . . .

The men and women's lavatories were without partitions. . . .

In operation on June 1, were twenty mess halls, each accommodating approximately 500 persons. Sixteen additional block mess halls, completed insofar as physical construction is concerned, were inoperative because of the lack of plumbing facilities and mess equipment. The hospital, personnel and high school messes had not been built. . . .

The hospital facilities at Manzanar on June 1, consisted of a 10-bed improvised hospital in one of the barracks buildings, an isolation ward, an out-patients' clinic and a children's ward. . . .

. . . . Manzanar has a single 500-gallon fire engine borrowed from the United States Forest Service. The fire department crew consisted of a fire chief, three Caucasion [sic] captains and thirty Japanese firemen split among three eight hour shifts. The camp is without a fire alarm system or an inter-barracks telephone system over which the ocurrence [sic] of fires might be reported. There is not a telephone to the hospital. During the night, the camp is patrolled by one Japanese for each area of three blocks. For the patrolman to report a fire it would be necessary for him to go by foot to the fire station. Each squad is drilled one hour daily in the use of the fire equipment and extinguishers.

Foamite extinguishers have been installed in the hospital units, each boiler room, laundry building and mess kitchen. Buckets of sand have been placed in the boiler room in each block; all available water barrels with buckets have been placed at strategic locations throughout the center, and residents have been instructed in the use of the improvised equipment until the fire department arrives. Locks have been ordered for fuse boxes to prevent solid fusing with pennies or other devices. Open fires are not allowed without a permit and no permits are issued on windy days after 2 p. m. [44]

CONSTRUCTION AT MANZANAR UNDER THE WAR RELOCATION AUTHORITY

After the initial 'basic construction' at Manzanar was completed by contractors working under the supervision of the Corps of Engineers, additional new construction, remodeling of existing structures, utility system extension, and refrigeration and land improvements became the responsibility of the relocation center's Engineering Section. Arthur M. Sandridge, who was appointed by the War Relocation Authority as Senior Engineer at Manzanar in June 1942, provided leadership for this section until February 1946. Sandridge was responsible to the Assistant Project Director in charge of Operations when that position was filled. Otherwise, he was responsible directly to the Project Director. The responsibilities of Sandridge included general supervision of the engineering program at Manzanar "so that the efficiency and standards of the section could be maintained for the operation, maintenance, and construction of the Relocation Center." He was also responsible for conducting a training program for supervisors and other appointed WRA personnel in the Engineering Section designed to acquaint them with the policies and methods for training Caucasian and evacuee employees in their respective units. Prior to leaving Manzanar in February 1946, Sandridge observed:

Very few of the Japanese in this Center were carpenters, plumbers, electricians, or trained for the other building trades. This necessitated the small appointed personnel, 8 to 14 people, to train and supervise the evacuees in construction and maintenance for this Center. To obtain a comparison of what this involved, imagine a city of 10,000 people without contractors or repair shops, where the city Engineer's office staff was responsible for training employees, operating the water and sewage plant system, electric distribution, steam plant for the hospital, all hot water boilers, distributing oil for cooking and heating, and doing all the repair work for the entire plant or city, and at the same time to construct houses complete for a staff of approximately 190 employees and their families, a chicken farm for 10,000 chickens, a hog farm for 500 hogs, to construct streets and roads, and an irrigation system for 350 acres of agricultural land developed for growing vegetables for the resident's food supply.

The problems of organizing and training crews for this work was more difficult, due to the fact the evacuees were only paid $16 to $19 per month but were furnished quarters and food whether they worked or not.

This program was carried out only by cooperation of the appointed personnel and the evacuees. A great many evacuees worked because of personal loyalty and respect for their supervisors.

Many of the evacuees learned trades such as, surveying, drafting, carpentering, plumbing, painting, refrigerator repairing, boiler and pump operating and to become electricians. . . . The maintenance problem was difficult for several reasons: first, because the temporary buildings deteriorated very fast and required constant repairs; second, because the original plans and construction, especially the utilities, were not planned for easy operation and maintenance. The electrical system had only one main switch which necessitated shutting off the electricity for the entire Center when any repairs were to be made. . . .

The water mains had valves for each six blocks which made it difficult to repair broken mains. . . .

Since the Center was laid out on a hillside with the hospital and blocks 6, 12, 18, and 24 at a higher elevation without any check valves in the water mains, consequently, they had a maximum water pressure of 26 pounds which would decrease to 16 pounds or below when the metal storage tank was low. This caused back siphon, making it necessary to install siphon breakers in the hospital and endangered the fire protection sprinkler system which was designed for 50 pounds pressure. This factor also made it necessary to maintain constant close supervision over the operation of the high pressure steam boilers. The lower part of the Center had an average pressure of 65 pounds which was adequate. [45]

New Construction

Staff Housing. In January 1943, Manzanar had nine family and 16 single apartments housing 29 WRA employees, one U.S. Post Office employee, and 22 dependents. Thirty-six WRA employees and 42 dependents lived in Independence, five miles north of the camp, Lone Pine, 12 miles south of the camp, and Cartago, 25 miles south of the camp. Seventy-seven employees and nearly 50 dependents were living in what Project Director Merritt described as "evacuee barracks so unsatisfactory that many employees have quit due to housing conditions." [46] Accordingly, the WRA determined in June 1942 to build wood frame housing for up to 250 staff members based on plans provided by the Farm Security Administration, including a combination of apartments for families and dormitories for single or married staff without children. [47]

Between January 15, 1943, and March 31, 1944, the WRA erected 19 buildings, having a combined area of 32,000 square feet, to house the center's appointed personnel at a cost of $110,633. The staff housing units, although temporary structures, were more substantial and commodious than the evacuee barracks, including among other things refrigerators, electric ranges, and space heaters.

Of the 19 buildings "14 were of the 4-family unit type, 3 were dormitories , and 1 was a central laundry." One of the "4-family unit type" structures served as a residence for the project director. Eighteen of the structures were constructed south and adjacent to the "administrative group." One four-family unit was built near the hospital group" for use by the center's Chief Medical Officer and appointive nurses.

The four-family unit staff buildings were divided into two two-bedroom and two one-bedroom apartments. Each apartment had a kitchen, living room, and bath. These staff buildings were "20 ft. x 94 ft., supported on three rows of concrete piers spaced 10 feet on centers the full length of the building." Girders "of 6 in. x "10 in. Douglas fir, built up from 2 in. x 10 in. timbers, supported 2 in. x 6 in. floor joists spaced 24 inches on centers." All walls and partitions "were framed from 2 in. x 4 in. Douglas fir excepting the dividing partitions between the apartments." The partitions were constructed with "2 in. x 8 in. plates, top and bottom, with staggered 2 in. x 4 in. studding spaced 24 inches on centers." The double partitions, as well as all water pipes for the adjoining baths and kitchens, were "sound-deadened with Kimsul insulating felt."

The rafters were "2 in. x 4 in. spaced 48 inches on centers with a 1 in. x 6 in. placed flat and midway between each set of rafters." The "1 in. x 6 in. redwood sheeting was securely nailed to the rafters and to the 1 in. x 6 in. which acted as a stiffener for the roof." Roofing was "the split-sheet type, each sheet overlapping the preceding sheet by more than half the width of the roll giving a double thickness to the whole roof."

The building exteriors were covered "with 1 in. x 6 in. V shiplap." A "1 in. x 3 in. sloping water table was placed around the building[s] 4 inches below the finished floor line, and the space below this point was boxed in with 1 in. x 6 in. redwood sheeting, forming a tight base to keep out cold, trash, animals, and the like."

All floors were "single thickness 1 in. x 4 in. tongue-and-groove Douglas fir." The "interiors of these buildings were lined with 3/8-inch plaster board," and "awning-type windows" were "used throughout." Cabinets were installed in each kitchen.

The three dormitories were "the same in type," as the four-family unit staff buildings. Each dormitory was "24 ft. x "140 ft. in size," and each building contained "10 double- and 3 single-bedrooms, 2 shower rooms, 2 toilets, "1 bathroom, 1 linen room, and 1 furnace room." The latter was used as a utility room and was equipped "with 2 double-compartment cement wash trays and a hot-water boiler."

The staff housing building at the hospital for the nurses and the Chief Medical Officer was "of the same type of construction, but was built 10 feet longer, 20 ft. by 104 ft." It contained "a 1-family apartment consisting of a kitchen, living-room, bath, and two bedrooms." The nurses' portion of the stricture was divided into "3 double- and 6 single-bedrooms, 2 bathrooms, 1 central living room, and a small kitchen."

The laundry building for the staff housing units was 16 feet x 20 feet and was equipped with tubs and a hot water heater.

Heating for the staff housing buildings, except for the dormitories, was supplied by "H.C. Little oil-burning space heaters." Hot water for the kitchens and bathrooms in the apartments was supplied by a "60-gallon H.C. Little automatic oil-burning hot-water heater, located in a 6 ft. x 8 ft. outside boiler room, built as an integral part of each building." Fuel for the space heaters and hot-water boilers was piped "from a 100-gallon tank centrally located outside and adjacent to each building." Flues were "of 22-gauge galvanized metal, one-piece construction."

The three dormitory buildings were heated from a "central heating plant" installed within the heater room of each structure. This plant consisted of "an H.C. Little D.A.C., size 2, oil burner with forced draft." The heat was forced through "overhead ducts into each room, and was regulated by wall registers." Hot water was supplied by a "60-gallon H.C. Little automatic oil-burning hot-water heater located in the utility room."

All staff housing buildings were supplied "with 120- and 220-volt electrical current, the former for lighting and the latter for cooking." The buildings were "painted two coats on the exterior wall, interior trim, and floors." The ceilings and interior walls were "painted with cold-water paint or kalsomine." [48]

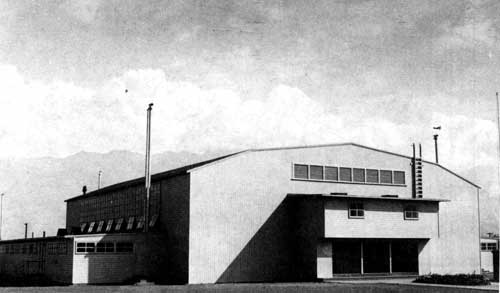

Gymnasium-Auditorium. The gymnasium-auditorium, generally referred to as the auditorium, consisted of 14/140 square feet of floor space, and was constructed between January 28, 1944, and September 30, 1944, at a cost of $30,355. The building was located in the firebreak between Blocks 7 and 13 and faced west to B Street. [49] A ceremony for laying the cornerstone of the building was held on February 19,1944. The ceremony featured musical numbers by the camp band and the high school chorus, a flag raising ceremony led by George Nishimura, high school student body president, and an address by Project Director Ralph Merritt and a response Kiyoharu Anzai, chairman of the Block Managers Security Administration, was the only building of the proposed "school group" to be constructed. Construction of other units for the schools was canceled, and "the school buildings that were used were provided by remodeling existing barrack-type buildings." Construction of the auditorium, which was expected to take three months, was delayed by labor shortages resulting from evacuee relocation and seasonal leave and absence of many young evacuee men who were serving in the military. [51]

Construction of the auditorium was supervised by O. E. Sisler, construction superintendent with direct supervision assigned to J. W. Lawing assisted by K. Kunishage, an evacuee resident at Manzanar. Construction of forms for the footings was commenced in early February 1944 by a crew of internees under the foremanship of I. Sakata. The mill work for the door jambs, casings, and interior finish was prepared in the carpenter shop in Warehouse 34 by Jimmy Araki and his evacuee crew. Electrical work was installed by R. D. Feil and an evacuee electrical crew. The plumbing and hot water systems were installed by K. Bowker and an evacuee plumbing crew. Painting and interior decorating was performed by J. Nakahama and an evacuee painting crew. [52]

The gymnasium-auditorium building was "classified as gymnasium type A." The aforementioned "Appraisal Report" noted that "the best of materials were used in this building." "Even the under floor and the inner sheeting" were constructed "of No. 1 fir and cedar lumber, much of it practically clear of knots or sap." It had an overall width of "118 ft. and a length of 119 ft." The main auditorium floor was "80 x 96 feet square." The stage at the east end of the main floor was approximately four feet high and "22 feet deep with an overall width of 30 feet." On each side and adjacent to the stage were dressing rooms that "provided space for equipment and stage trappings." A "wooden truss, supported on each end by wooden columns, supported the proscenium arch which had a clearance of 12 feet from the finished floor."

One-story shed-type sections were constructed along "the full length of the main section, and, on each side" of the building. These sections housed "the toilets, dressing-rooms, lockers, and offices." The "one-story shed-type section on the south side" of the building "extended 40 ft. 9 in. beyond the east end and was used as a health unit."

The auditorium building was built "on piers placed approximately 8 feet on centers each way." Girders were "of 6 in. x "10 in. material with 2 in. x 6 in. floor joists, spaced 12 inches on centers." All floors were "double." The subfloor was "of 1 in. x 6 in. Douglas fir shiplap laid diagonally," while the finished floor was "1 in. x 4 in. tongue-and-grooved Douglas fir, sanded and varnished."

The walls of the main section of the building were "of double thickness of 1" lumber" and "20 feet high." Posts, "12 in. x 12 in., supported five Pratt-type wooden trusses." The trusses were constructed with "split ring connectors and bolts." The ceiling joists were "of 2 in. x 6 in. material." Roof purlins were "2 in. x 10 in. lap jointed at each end and solid at each lap." Diagonal sheeting "was laid over the purlins," and "split-sheet roofing was applied, mopped on with hot asphalt."

A "shed-type roof" was built "over the stage," using "2 in. x 12 in. joists spaced on 24-inch centers with 2 rows of solid bridging." "Sheeting of 1 in. x 6 in. shiplap was laid," and "split-sheet roofing was mopped on."

A concrete porch was built across the (west) front of the building "for an entrance to the three sets of double doors." Above the porch was a "moving picture projection booth, 8 ft. 6 in. x 30 ft. 11 in." The booth was divided into two rooms — "one for the machines and other for the rewinding of the films." Both rooms were "lined with fireproof asbestos board." Two inside stairways led from the main floor to the booth, providing "access and a means of escape in case of fire."

The one-story shed section, housing the toilets, dressing rooms, locker rooms, and health unit, was constructed "with 2 in. x 4 in. studding, with 2 in. x 12 in. rafters spaced 24 inches on centers, and bridged with solid blocking, sheeted and roofed, the same as for the other portions of the building."

The exterior wail finish was "1 in. x 6 in. V shiplap painted to protect it from the weather." The interior wall finish was "of the same material." The auditorium ceiling was finished with "1/2-inch fibre board applied to the ceiling joists flush with the underside of the bottom cords of the trusses." All ceilings in other portions of the building were "of the same material."

Heating for the building was provided by "H.C. Little forced draft automatic oil heaters." The heaters were placed "in the most strategic points." Two were under the stage and "forced the heat directly into the main auditorium through screened grills." Two others "were placed at the front, in the room adjacent to the main floor, and supplied heat in [the] main room." Two others were connected "to overhead ducts and forced the hot air through the grills into the toilets, shower rooms, and offices." The dressing rooms and the health unit were provided with "independent space heaters."

The hot-water system consisted of a "250-gallon Hanson boiler located under the stage and connected with necessary piping running from this point to the health unit, showers, wash rooms, and toilets."

Electric wiring was installed "for the proper illumination and operation of all equipment including four Trane 15 P. projector fans installed in the ceiling of the auditorium." Special "footlights and overhead lighting were provided for the stage." [53]

The still-unfinished auditorium was first used for a performance of the operata "Loud and Clear," written and directed by Louis Frizzell, the Manzanar high school music instructor, on June "16,1944. Two days later the graduation ceremony for 177 high school students was held in the auditorium. Visitors from Bishop, Big Pine, Independence, and Lone Pine attended the operata, and more than 1,000 persons attended each event. During the following three months, construction of the auditorium was completed. Considerable "finish carpenter work" and installation of heating units and hot air ducts, as well as painting and landscaping, was completed by September 30. [54]

Poultry Farm. The poultry farm, consisting of 16 buildings having an aggregate floor space of 29,528 square feet, was constructed between July 8, 1943, and December 31, 1943, at a cost of $21,784. The complex was located "south and west of the Center, adjacent to the fence surrounding the Center." The building complex consisted of two warehouses connected at one end, eight brooder houses, and six laying houses.

The warehouse and office building "was of U-type construction with an overall area" of nearly 3,800 square feet. The warehouse or feed storage space was located "in the two wings, each wing being 20 ft. x 60 ft. with a total floor area of 2,400 sq. ft." The office and egg-storage rooms were "each 16 ft. x 20 ft.," and the dressing and packing room "which connected the two wings was 20 x 30 ft." A butane-fired scalding kettle, used for dressing poultry, was installed in the latter room.

The building was built with "a continuous concrete footing which projected 6 inches above the finished floor line." All floors were "of concrete, troweled to a smooth finish." The walls were constructed "of 2 in. x 4 in. studding plates." The studding was "cut 7 feet long and spaced 2 feet on centers." The walls were completed "by 1 in. x 6 in. sheeting covered with 15-lb. building paper held in place with 3/8 in. x 2 in. batts."

The rafters were "of 2 in. x 6 in. material with 2 in. x 4 in. cross ties and bracing spaced 3 feet on centers, covered with 1 in. x 6 in. redwood sheeting and split-sheet roll roofing." The windows were "4 ft. x 2 ft. 4 in. frameless, awning type."

The eight brooder houses were "14 ft. x 24 ft., divided into two equal-sized rooms, each being large enough for the brooding of 500 baby chicks.": The floors and foundations were "concrete with the foundation walls projecting 6 inches above the finished floor as a protection against flooding from the storm waters." The studding was "of 2 in. x 4 in. material, spaced 2 feet on centers, cut 6 ft. 6 in. for the back wall and 7 ft. 6 in. for the front wall, making a shed-type roof." The rafters were "2 in. x 4 in. material, spaced on 4 feet centers with 2 in. x 4 in. supports running at right angles to the rafters." Roof sheeting was "1 in. x 6 in. redwood covered with split-sheet roll roofing."

The walls were sheeted with "1 in. x 6 in. shiplap, painted to protect it from the weather." The windows were the "frameless awning type." "Kerosene-burning brooders" were used, vented "through the roof with 6-inch galvanized piping." Outside runs constructed "of chicken netting and wood posts" were constructed the full length of each brooder building. The runs were "16 feet wide and were divided in the center with fencing of the same type."

The six laying houses were each "20 ft. x 192 ft., divided into eight units per building." Each unit had an area of "20 ft. x 24 ft., large enough for the housing of 175 hens." The floors and foundations were "of concrete, the foundation projecting 6 inches above the finished floor" for ease in cleaning.

The walls were framed from "2 in. x 4 in. material, cut 7 feet long and spaced 2 feet on centers with 2 in. x 4 in. plates, top and bottom." The siding was "1 in. x 6 in. shiplap while the roof was framed with 2 in. x 4 in. rafters and 2 in. x 4 in. cords, each set braced to form a truss." They were spaced "4 feet on centers and sheeted with 1 in. x 6 in. redwood." "Split-sheet roll roofing" was used. The dividing partitions "between each unit was 1 in. x 6 in. shiplap with 2 in. x 4 in. studding." Each section was provided with "a 2 ft. x 2 ft. roof vent equipped with a trap door for the regulation of heat and air." "Sufficient roosts and laying boxes" were installed "to adequately care for the maximum number of hens housed in each section." The exteriors "of all buildings were painted to protect them from the weather."

"Outside runs, 20 ft. x 24 ft., of 2-inch mesh chicken wire and wood posts" were constructed for each section or compartment. "Wood feeding troughs" were built "for the feeding of mash and other feed."

Each building in the group was provided with running water "piped in from the center mains" and lighted by electricity "from the connections to the lines within the Center." [55]

Root Cellar. A 2,600-square foot (26 feet x 100 feet) root cellar was constructed between July 5 and October 28, 1943, at a cost of $1,438. The cellar, located in the area west of the former camouflage factory buildings, was designed to provide storage for approximately four tons of root vegetables grown on the Manzanar farm.

Three-fourths of the structure was below ground surface. An excavation was made "6 feet in depth and sufficient in size to receive the building." A continuous footing of concrete was poured across the ends down both sides." Two footings "running lengthwise and spaced 10 feet in from the outside line of the building" were constructed. A "2 in. x 6 in. mud sill was bolted to the outside footings and 2 in. x 6 in. studding 8 feet long, spaced 18 inches on centers with a double 2 in. x 6 in. plate" was installed.

A "2 in. x 6 in. plate" extended through the interior of the building and rested on the interior footings. From this plate and extending to "6 in. x 6 in. girders that supported the rafters, 4 in. x 6 in. posts were placed spaced 10 feet on centers and securely braced with knee braces to the 6 in. x 6 in. plates." Two rows of these posts, "3 feet from the center line of the building, acted as supports for the rafters."

The rafters of the building consisted of "2 in. x 6 in. Douglas fir with 2 in. x 6 in. Douglas fir cords." The roof sheeting was of "1-in. Douglas fir securely nailed." The roof was "90-lb. mineral-surfaced felt roofing."

A center runway, "6 feet wide," extended the "full length of the building" and was "flanked on both sides with storage bins." The bins were equipped "with 1 in. x 6 in. wood floors with 1-in. spacing between the boards which rested on 2 in. x 6 in. floor joists spaced on 24-inch centers raised sufficiently from the ground to allow free circulation of air." Ten bins were installed on each side of the runway, "partitioned off with 1 in. x 6 in. boards with a 1-inch space between each."

Air vents were installed over each bin. They were "2 feet square and extended 2 feet above the finished roof." They were equipped with "manually operated dampers."

The inside of the exterior wall was covered with "1 in. x 6 in. boards from floor to plate line, spaced 1 in. apart."

The outside of the exterior walls was covered with "1-inch random sheeting from the top plate line half way to the mud sill." From this point, an "air vent extended from the front of the building down both sides and connected with a 3 ft. x 3 ft. tunnel vent located in the center of the rear end." The air vent around the building was built by "placing 2 in. x 4 in. supports cut on a 45-degree angle and attached to the studding at a point corresponding to the exterior wall sheathing." The "air-vent rafters or supports were covered with heavy building paper to prevent moisture from entering the building."

A "double refrigerator-type door, 6 ft. x 8 ft.," was installed in one end of the root cellar.

A dirt ramp was graded from "regular grade to the building entrance," providing "easy loading and unloading facilities for produce delivered to and from the building." The building was connected with an electric line to provide light.

The root cellar construction was completed "by back filling around the walls" and "covering the roof with a layer of straw topped off with 8 inches of clay." [56]

Hog Farm. The hog farm, constructed between September 1, 1943, and April 30, 1944, at a cost of $7,615, was located "2,600 feet from the southwest corner of the Center."

The hog farm's feed storage building was "20 ft. x 80 ft. with the floor and footings of concrete," The footings projected "6 inches above the finished floor" to prevent water from entering the structure and damaging the stored feed. The walls were "8 feet in height, framed with 2 in. x 6 in. studs and plates." The studdings were placed "4 feet on centers with one 2 in. x 6 in. horizontal nailing girt spaced half the distance between the top and bottom plates." Double doors, "6 ft. x 8 ft. were placed in each end." The siding was "1 in. x 8 in. D. F. sheeting covered with "15-lb. building felt held in place by 3/8 in. x 2 in. batts."

The rafters were "2 in. x 4 in. Douglas fir spaced 4 feet on centers." Each set was trussed with "2 in. x 4 in. cords and braced with knee braces on each third set." The roof was sheathed "with 1 in. x 12. Douglas fir and covered with 90-lb. mineral-surfaced roofing."

The farrowing pens and houses were constructed as a unit. They were "sheds 4 feet high on the back and 6 feet high on the front." Studs, "2 in. x 4 in., were used with 1 in. x 6 in. sheeting." The roof was "covered with 45-lb. roll roofing." Each house was divided into "six pens or sections 8 ft. by 5 ft. each with doors both front and rear connecting to outside pens." The pens on one side were provided "with cement floors for feeding." A "concrete gutter or trough, 12 inches wide and 4 inches deep" extended "the full length of the feeding platforms." This gutter was used as a catch trough for non-edible material.

Three hog houses, each "20 feet square, with a partition" equally "dividing the floor space" were constructed. The structures were built from "rough 1-inch material with 2 in. x 4 in. posts." They had "shed-type roofs, 4 feet high on the low side and 6 feet high on the high side." Each house was surrounded "by board panel fencing." The fencing consisted of "2,070 lineal feet," using "250 posts, 4 in. x 4 in. x 6 ft." and "8,280 lineal feet of rough 1 in. x 6 in. material was used in the paneling." Additional pens were built in which "864 lineal feet of 30-inch hog-fencing and 108 4 in. x 4 in. x 8 ft. posts were used." A "4,310 sq. ft." concrete platform or deck was constructed for feeding.

Water was piped from George Creek to concrete watering troughs in each pen. An electric line was extended from the center to the hog farm to provide electricity for lighting. [57]

Industrial Latrines. Two industrial latrines, having a combined floor area of 768 square feet, were designed and constructed by Ryozo F. Kado, an evacuee stonemason, in the warehouse section of the industrial area at Manzanar between September 8 and November 1, 1943, at a cost of $2,433. The latrines were each "16 ft. x 24 ft. with a center partition separating the men's section from the women's." The foundations and floors were concrete. Studdings, "2 in. x 4 in. x 8 ft. and spaced 2 feet on centers," were covered with "1-inch sheathing and building paper held in place by 3/8 in. x 2 in. batts."

The roof was framed from "2 in. x 4 in. material." The rafters were placed on "3-foot centers, sheathed with 1-inch material, and roofed with split-sheet roll roofing." Windows were of "the frameless awning type, size 4 ft. x 2 ft. 4 in.," while the doors were made "from the material on hand." The women's section was equipped with "five toilets, a wash basin, and a floor drain." The men's section was equipped with "three toilets, two urinals, a wash basin, and a floor drain."

Cold water was supplied by tapping "the main water line," but no "hot water facilities" were provided. A small "oil-burning space heater" was installed in each room as a protection against freezing during periods of extreme cold. [58]

Garage. A garage was constructed "in the motor pool area 60 feet west of the old garage" between November 20, 1944, and April 23, 1945, at a cost of $2,301. The construction was "justified by an acute shortage of space for the repair and maintenance of automotive equipment."

The garage had "a frontage of 48 feet and a depth of 30 feet," with "concrete floors, footings, and a 6-inch concrete curb to keep storm waters from flooding the floors." The garage was divided "into three stalls of equal size — one stall for lubrication, one for washing, and the other for painting."