|

MOUNT RAINIER

Wonderland An Administrative History of Mount Rainier National Park |

|

| PART FOUR: DEPRESSION AND WAR YEARS, 1930-1945 |

X. VISITOR USE IN THE DEPRESSION ERA

INTRODUCTION

The Great Depression had a mixed effect on people's ability to visit Mount Rainier National Park. Hard times kept many people away who could not afford the cost of a trip, even a weekend trip, to the national park. This was reflected in the annual visitation statistics for Mount Rainier, which fell by 25 percent from 1931 to 1932, and by an additional 21 percent from 1932 to 1933. These were the worst years of the Depression. But hard times had an opposite result, too, as widespread unemployment and underemployment gave people more leisure time. After the hardest years of the Depression had passed, annual visitation to Mount Rainier picked up and soon exceeded what it had been in the 1920s. Nationwide, automobile and gasoline sales rebounded after 1933 and resumed their phenomenal growth of the preceding decade. Travel expenditures for the whole country rose during the years 1934 to 1937, dipped slightly during the 1938-39 recession, and rose spectacularly in 1940-41. Reflecting these trends in the national economy, annual visitation to Mount Rainier showed a 71 percent increase over the whole decade (from 265,620 people in 1930 to 456,637 in 1940).

The Depression affected visitors' lodging preferences in Mount Rainier National Park more than it influenced total visitation. Park hotel patronage declined sharply during 1931-33 and remained depressed throughout the era. Meanwhile, campground use increased in both relative and absolute terms. Again, this reflected national trends. According to automobile historian Warren James Belasco, "Tourists economized on operating expenses, mainly room and board, in order to keep cars running. Expenditures for hotels, restaurants, vacation clothing, and travel supplies fell from $872 million in 1929 to $444 million in 1933." [1] Belasco documents how the autocamps and the nascent motel industry grew during the Depression years while the hotel business suffered. The rise of the motel in American life changed visitor demand in Mount Rainier National Park. Tourists who could ill-afford a room in the Paradise Inn wanted to stay in small "housekeeping" cabins, not the tent cabins of yesteryear. The RNPC built hundreds of housekeeping cabins at Paradise and Sunrise to meet this new demand. Other significant changes in visitor use in the 1930s included the advent of winter sports at Paradise and increased summer use of the Sunrise-White River section of the park.

SUMMER RECREATION

There were two broad trends in summer recreational use in the 1930s: a trend toward greater distribution of use among the four corners of the park, and a trend in favor of activities that were self-guiding or free-of-charge. One trend related to new road development, the other to the deepening economic depression.

Road access to all four corners of the park affected visitor distribution. As numbers declined overall, the percentage of visitors going to the less developed sections of the park increased. Visitor use of the Carbon River and Ohanapecosh areas increased relative to the more developed Sunrise and Paradise areas. Visitor use of the Longmire-Paradise area stayed about double that of the Sunrise area.

Park visitors were inclined to be more thrifty and independent than they had been before the Depression. The RNPC's restaurant sales shrank dramatically while use of the park's picnic areas rose. Occupancy rates in the hotels fell more sharply than overall park visitation, and souvenir sales were so depressed that the company did not even open its photograph business in 1933. Fewer visitors availed themselves of the company's guide service, preferring to hike on foot, explore the trails without a guide, or take free nature walks led by park naturalists. [2]

Company officials accepted most of these setbacks with equanimity. They were less gracious about the decline in patronage of the RNPC's commercial guide service. They saw the surge of interest in the NPS 's free educational program—its ranger-led nature walks, evening lectures, museum exhibits, and self-guiding nature trails—and they argued that the ranger-led activities were cutting into their guide business, perhaps interfering with their contractual rights.

Two explanations were given for the growing visitor preference for the NPS guide service over the RNPC guide service. Company officials assumed that it was purely economic: hard times were forcing park visitors to seek out free services wherever they were available. The NPS's free nature walks, lectures, and museums were touted in Seattle and Tacoma newspapers. [3] NPS officials, on the other hand, believed that the trend was independent of the Depression. After all, the educational program was already enjoying great popularity in the 1920s when it was still relatively small. They regarded the growing number of "public contacts" made by the Naturalist Department in the 1930s as a reflection of the organization's growing size, resources, and professionalism. [4] They saw the evolution of the park's educational program as a response to longterm trends in visitor demand.

The NPS did not want to take business away from the RNPC. It supported the company's guide service on principle. The company could ill-afford the loss of guide business in the early 1930s. But the NPS did not want to limit its own educational program on the company's behalf, either. The park administration worked out a cooperative plan with the company in 1931, but the plan was short-lived. Half way through the summer of 1933, the company withdrew from the cooperative program and started providing its own talks at another location. Superintendent Tomlinson responded to this challenge by suspending all naturalists' lectures and all but the shortest ranger-led nature walks. The result was just as he had anticipated: hundreds of visitor complaints provided proof that there was a public demand for "authoritative informational service in the National Park." [5]

Meanwhile, increasing numbers of park visitors availed themselves of neither service and simply struck off on their own. Two self-guiding nature trails, the Trail of the Shadows at Longmire and the Glacier Trail to the terminus of the Nisqually Glacier, were used by tens of thousands of people each summer. Longer trails saw increasing use by people without guides, too. The result was an increasingly varied pattern of summer recreational use. The pattern deserves a closer look.

Paradise

The Paradise meadows and the surrounding area continued to be a focal point for visitors to Mount Rainier. The Skyline Trail, a five-mile loop trail that took in Alta Vista, Glacier Vista, Panorama Point, Timberline Ridge, and Mazama Ridge, remained the most popular horse trail in the park. RNPC trail guides led parties on the half-day ride morning and afternoon. Much of this route lay over melting snowfields until late summer. What the horse traffic must have done to the delicate alpine meadows can only be imagined; damage to the plants and wildflowers from trampling would not be evaluated or monitored until many years later. Other popular horse trips went to the Reflection Lakes and the foot of the Tatoosh Range. The RNPC's guide service offered regular foot trips to Nisqually Glacier, Paradise Glacier, and Pinnacle Peak. The NPS encouraged tourists to get out on the glaciers as long as they were with experienced guides. [6]

|

| A party of CCC boys visiting the Paradise ice caves. (O.A. Tomlinson Collection photo courtesy of University of Washington, Negative No. UW14013) |

Many tourists hiked on their own up to the Anvil Rock lookout and the rock shelters at Camp Muir. Tomlinson once remarked that the latter, dating from 1916 and 1921, were "used extensively by amateur climbers and others who hike about aimlessly and improperly equipped for hiking or climbing at that altitude." [7] When a visiting official recommended that the NPS install a telephone line to Camp Muir, Tomlinson noted that "undoubtedly if the telephone was placed in Camp Muir, hundreds of casual hikers who reach that point would keep a telephone line more than busy with idle and unnecessary gossip." [8] Such comments suggest why the NPS favored guided walks in the Paradise area. The high altitude, glaciers, and sheer cliffs in the Paradise area presented a multitude of hazards.

The Paradise ice caves were a popular attraction. It was a unique experience to look up at the blue, green, and pink light filtering into these great rooms under the Paradise Glacier. Due to the rapid melting of the Paradise Glacier, the caves changed from year to year. As the last winter's snowpack melted off each summer, the RNPC's guide service sped the process along by chopping or blasting out openings in the ice large enough for people to enter. Normally this occurred toward the end of the summer, but in 1932 the RNPC requested permission to dynamite a hole in the ice in July, so that this popular attraction could be made available earlier. After some philosophizing about the problem of "forcing nature," Cammerer gave his approval. [9] As Tomlinson pointed out, the ice caves were a good source of revenue to the company's guide department, and with business ailing "the pressure is greater than ever for hastening the opening of the Paradise Ice Caves." [10]

The lingering snowpack around the Paradise area held its own attractions. "Nature coasting" was a popular and much-photographed activity. A popular postcard image of Mount Rainier in the 1920s and 1930s depicted a line of people—usually young women—seated on a steep snowfield one behind the other in stairstep fashion. These were tin-pants sliders, or "nature coasters." [11] Floyd Schmoe described this activity in his reminiscence of his year with the RNPC guide service.

On the usual half-day guide trip [to the Paradise ice caves] we always made a long circle on the glacier and had several slides of two or three hundred feet as well as many shorter ones. On the short steep slopes we sent people down singly with a guide at the bottom to pick them up, but on long gentle slopes we all sat down with each man holding the feet of the one behind him. When all were ready the guide in front would lift his feet and the guide behind would shove off and the entire party would serpentine down the glacier whooping and yelling. It was good sport and no one was ever hurt much. [12]

On August 1, 1931, the RNPC opened a nine-hole golf course at Paradise. [13] This short-lived venture was another attempt to bring the RNPC more business and counter the effects of the Depression. RNPC President H.A. Rhodes put the idea to Director Albright when he inspected the park in 1930. Albright agreed with Rhodes that a golf course might entice local people to stay at the Paradise Inn during the week. He rejected Rhodes's proposal for a miniature "Tom Thumb" golf course. Albright wrote in a memorandum afterwards, "Golf is a country game not a city one. It can be justified in parks easier than tennis. Anyway, I want to try out the thing and as the Rainier Company needs revenue more than any other Company I am disposed to let them try the experiment." He put Tom Vint in charge of its design. [14]

With the completion of the south side road to Reflection Lakes, this area began to attract crowds as never before. In 1934, the NPS authorized construction of a "boat house-comfort station" on the shore of the lake. The building was a small public works project. Boating, fishing, and picnicking on and around the lake became more and more popular. [15] The RNPC guide department offered fishing trips from Paradise to Reflection Lakes with hiking gear, fishing tackle, and boat provided. [16]

Another distinctive tourist attraction during the Depression was the presence of the Civilian Conservation Corps (see Chapter XI). President Roosevelt's "Tree Army" received substantial press coverage, and tourists were curious to see these vaunted young men in action. For most of the CCC's existence, from 1933 to 1942, there were six CCC camps in Mount Rainier National Park, the most accessible one being at Narada Falls. All RNPC busses made the Narada Falls camp a regular stop for tourists enroute to Paradise. Hundreds of private automobiles also stopped at Narada Falls each day during the summer. The waterfall itself drew many onlookers, of course, but it was the camp superintendent's feeling that most people were primarily interested in seeing what a CCC camp looked like. "Owing to the fact that this camp is under constant observation by the public in general," wrote the camp superintendent, "a special attempt has been made by this camp to present a smart appearance." [17]

Camp Narada occupied the level ground on the far side of the stone bridge directly above Narada Falls. Beyond the decorative log entrance to the camp were a handful of permanent buildings consisting of garages, mess hall, wash houses, and tool shops. These were laid out on either side of a short section of abandoned road. Nestled against a wall of trees were the tent quarters of the company officers and men.

Interestingly, the site was selected for a CCC camp over the protests of NPS landscape architects who thought the area ought to be restored to a natural condition. The site had formerly seen use by road crews and seasonal rangers assigned to traffic control. Some effort had been made to clean up the area in the late 1920s with the removal of an unsightly toilet building at the brink of the falls and the clearing of a mass of downed trees from the Paradise River directly above the falls. After the camp's abandonment in 1937, the landscape architects were once again thwarted, as several of the buildings remained standing for equipment storage. [18]

Sunrise

Throngs of tourists drove up the new road to Sunrise after its opening on July 15, 1931. Each succeeding weekend brought more people, and on three weekends during August the travel to Sunrise exceeded that to Paradise. [19] Tomlinson was jubilant, confidently predicting that in the following year, with the expected completion of the road over Chinook Pass, travel to Sunrise would nearly double what Paradise received. That did not happen, however. The pattern of visitor use soon stabilized the other way, with about two times the number visiting Paradise each summer as visited Sunrise.

The Sunrise development confirmed the park's growing orientation to the private automobilist. The most popular attraction in the entire new development in the northeast corner of the park was the Sunrise Point parking area and overlook. As described earlier, this was a carefully designed switchback on the road from White River up to Yakima Park. As the new road gained the crest of Sunrise Ridge, it made a broad, 180-degree turn that provided the automobilist with a panoramic view in all directions. A large parking bay inside the turn and pedestrian bays around its perimeter completed this site's functional design. Hundreds of cars packed into the Sunrise Point parking area each day. At the end of its first season of use Tomlinson wrote approvingly, "Perhaps the fact that this vantage point is on the main highway where the visitor may, from the comfortable seat of his automobile, enjoy all the thrills of the mountain climber, had something to do with its popularity." [20] The park administration was satisfied if most park visitors came only for the pleasure of the road and its scenic views.

There were opportunities for nature study and recreation at Sunrise for all those who would take advantage of them. The NPS improved the trail system around Yakima Park to accommodate the new crowds of people. The most popular walk was the Rim Trail. Within a modest 800 feet of the parking area and ranger station, the visitor could gain an unobstructed view of the massive Emmons Glacier for its whole length from the summit of Mount Rainier to its terminus in the White River Valley below. Other trails followed easy grades up the slope behind the plaza and turned east or west near the crest of Sourdough Mountain, yielding occasional grand views to the north as well as a constant view of Mount Rainier to the southwest. In that era of better air quality, it was possible on a clear day to see northward all the way to the Selkirk Range in British Columbia. Beginning in 1931, a ranger-naturalist was duty-stationed at Sunrise to answer questions, give lectures, and lead nature walks. Longer hikes to Burroughs Mountain and Berkeley Park were also available to the visitor at this time. [21]

Visitors to Sunrise also found a variety of guided trips and amenities provided by the park concession. Regular half-day horse trips could be purchased for $3.00. Small and plain "housekeeping cabins" could be rented for $2.50 per day with blankets and linen, or $1.50 per day without. In the Sunrise Lodge, which first opened in 1931, the visitor could rent bathtub, shower, and laundry facilities; purchase groceries; and enjoy cafeteria-style dining. [22] By 1934, a free public campground and picnic area had been established near Shadow Lake, less than a mile west of the Sunrise plaza. [23]

Backcountry Use

The vast majority of visitors to Mount Rainier in the 1930s did not go very far into the backcountry. If they left the immediate vicinity of their automobiles at all, they generally kept to the popular day trips around Paradise, Longmire, and Sunrise. There were practical reasons for this pattern of recreational use. Few people owned the necessary equipment to go into the backcountry. The park concession outfitted parties and offered guided horse trips around the mountain, but these were beyond the means of most visitors. The company's general manager, Paul Sceva, remarked in 1932 that 99 percent of park visitors never ventured more than a mile from the Paradise and Sunrise areas. [24]

Nevertheless, backcountry use grew into an identifiable activity during the 1930s. Increasing numbers of Americans made a distinction between wild country that could be visited by car and wilderness that was only accessible by foot or horseback. Organizations like the Wilderness Society, founded in 1935, and older mountain clubs such as The Mountaineers, argued forcefully that road development threatened to overwhelm the relatively few remaining areas of countryside that could be reached only by non-mechanized means. The absence of automobile access became the defining quality of American wilderness. The effort by The Mountaineers in 1928 to get the NPS to set aside the northern section of Mount Rainier National Park as an undeveloped, roadless area, or "wilderness area," anticipated a much wider protest in the 1930s against too much road-building in the national parks and national forests. Against this backdrop, backcountry use became more strongly differentiated from other forms of recreation in Mount Rainier National Park than it had been before.

Evolving ideas about wilderness were one significant factor in stimulating more backcountry use. Another factor was that the logistics of backcountry travel in Mount Rainier were becoming easier. In the 1920s, it generally required from twelve to fourteen days to hike the Wonderland Trail around the mountain. In the 1930s, the trip could be accomplished in about eight to ten days. With the completion of the road to Sunrise, backpackers could lighten their loads by first depositing a food cache there or at the Carbon River Ranger Station, or at both places, for resupply as they came around the mountain. [25] Moreover, trail conditions were improved and the route was significantly shortened in a few places. Estimates of the Wonderland Trail's original length varied from 100 to 115 miles; today it is given as 93 miles. [26]

The NPS encouraged greater use of the backcountry. Park naturalists urged visitors to get out onto the hiking trails. As early as 1921, the superintendent had recommended the establishment of four or five "hotel camps" at intervals on the Wonderland Trail in order to facilitate this trip. [27] Although that plan never materialized, the NPS developed a system of free public shelters instead. With the help of the CCC, the number of backcountry shelters proliferated. The trail shelters differed from backcountry patrol cabins in that they were generally three-sided with earthen floors and were intended for public rather than administrative use. [28] By the mid-1930s, there were perhaps a dozen trail shelters in the backcountry, making it possible to spend each night in a shelter while hiking around the mountain. [29]

The RNPC also encouraged the use of the trails. The company advertised guided horse trips around the entire Wonderland Trail as well as shorter trips along segments of the trail. At the beginning of the decade, the company provided an outfit, food, and a guide for $25 per person per day, with discounts for larger parties. In an effort to increase business, the RNPC slashed its rates by one third for 1933 and offered new overnight trips from Sunrise to Mystic Lake and from Paradise to Snow Lake in the Tatoosh Range. General Manager Sceva thought the company had "a golden opportunity because of the financial condition of the country to hold people in the park perhaps longer than before." These initiatives had the full encouragement of the park administration. [30]

The economic hard times contributed to one other form of backcountry use in the 1930s: poaching. In October 1932, two men were arrested for hunting in the park. Owing to the fact that the men had been unemployed for some time, the U.S. commissioner decided to waive their fines. He merely confiscated their guns. Superintendent Tomlinson and Assistant Director Cammerer both concurred with his decision. [31] Naturally there is no reliable record of the amount of poaching in the park, but one could surmise that it increased during the Depression owing to the desperation of many people in the area.

Summit Climbs

After a surge of interest in climbing to the summit of Mount Rainier in the early 1920s, this activity attracted no more than a few hundred people each season. [32] The most popular route was the Gibraltar route, pioneered by Stevens and Van Trump on their historic first ascent in 1870. The route featured a traverse of Gibraltar Rock by way of a long, narrow ledge. In 1936, a section of this ledge avalanched away, making the route impassable, and from that year forward a variety of other south-side routes were used. [33] Still, the basic pattern of the ascent remained the same: climbers departed from Paradise at mid-day and hiked up alpine meadows, scree and snowfields to Camp Muir, at 10,000 feet elevation. Starting out from there a few hours before sunrise, climbers proceeded to the summit before the snow turned soft in the heat of the day, and then retraced the full distance back to Paradise by nightfall.

Most summit climbers were either experienced themselves or accompanied by experienced guides. The few amateurs who tried to climb the mountain on their own, usually without suitable equipment, caused the park administration grave concern. In December 1927, the president of The Mountaineers, Edmond S. Meany, alerted Superintendent Tomlinson to the fact that one Lionel H. Chute planned to take his troop of Boy Scouts on a foolhardy winter ascent of Mount Rainier. Despite the entreaties of both Meany and Seattle Boy Scout Executive Stuart P. Walsh that he cancel the trip, Chute intended to go anyway. Tomlinson wrote to Mather that there was an urgent need for a regulation authorizing the ranger force to prevent visitors from undertaking hazardous stunts like this. Not waiting for a reply, the superintendent advised Chute that all trails to the summit were closed. This action prevented Chute from going and may have saved lives. Before the next summer season, the park had rules for summit climbers. [34]

The climbing rules required all parties to register with the district ranger. Parties which did not have a professional guide or were not affiliated with a recognized mountain club were required to show evidence that they were competent and properly equipped. Required equipment consisted of climbing boots and crampons (or their equivalent), woolen clothing, colored glasses, gloves or mittens, alpen-stock or ice axe, and climbing rope. [35] The rules were strictly enforced, particularly after climbing accidents claimed the lives of two men in 1929 and another man in 1931. Even so, improperly equipped parties sometimes gave rangers the slip. In 1931, rangers spotted through binoculars an unregistered party on the summit dome. Confronting the climbers that afternoon at Camp Muir, they found that the group of five had only one alpen-stock between them and that they were all shod in tennis shoes. [36]

WINTER RECREATION

Winter use of Mount Rainier National Park grew significantly during the 1930s. Most people who visited the park during the winter came either to ski or to watch one of the several ski events held at Paradise; thus, winter use in the 1930s was practically synonymous with skiing. The nature of skiing itself changed in the 1930s, as downhill racing overtook cross-country touring as the most popular form of skiing.

The Developing Sport of Skiing

It was in the 1930s that Americans discovered the European sport of downhill skiing. The first American ski school, with European ski experts providing instruction, opened in New Hampshire in 1929. Three years later, winter sports received a big boost when the third winter Olympics were held in Lake Placid, New York. Two years after that, in 1934, the first rope tow in the United States was installed at Woodstock, Vermont. It was powered by the rear wheel of a jacked-up Model T Ford. Despite some early technical difficulties with this contraption, the idea quickly spread to the West. By the mid-1930s, there were new, rope tow-equipped ski hills from Wilmot Hills, Wisconsin, to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, to Stevens Pass, Washington. [37]

Downhill racing events began to draw spectators and the national media. The First National Downhill Championship was held at Mount Moosilauke, New Hampshire, in 1933. The First U.S. National Downhill and Slalom Championships were held at Paradise, Mount Rainier National Park, in 1935. It was at this event that the American team for the fourth Winter Olympics was selected. In 1937, the first Harriman Cup race was held at the Union Pacific Railroad's new ski resort of Sun Valley, Idaho. [38]

Personalities also contributed to the growing popularity of downhill skiing. Alpine skiing techniques were introduced to American skiers by a flock of prominent German and Austrian skiers who fled Hitler's Germany in the mid to late 1930s. Austrian champion Otto Schniebs attracted ski disciples at Dartmouth. Hannes Schneider, another Austrian, taught skiing in Conway, New Hampshire. Friedl Pfeiffer went to Sun Valley; Sepp Ruschp to Stowe; Luggi Foeger to Yosemite; and Otto Lang to Mount Rainier. [39]

Skiing also grew more commercialized in the 1930s. Clothing and equipment manufacturers moved to exploit the new market. The first two public ski shows, held at Madison Square Garden and Boston Gardens in 1934, drew thousands. Alf Nydin of Seattle founded SKI Magazine, the first magazine devoted to the winter sport, in 1935. The Union Pacific Railroad built the nation's first destination ski resort, replete with chairlift, at Sun Valley the next year. The site was selected by Austrian alpine expert Count Felix Schaffgotsch, who considered and rejected Paradise along with a handful of other western locations. According to SKI Magazine, the Sun Valley development "startled the fledging American ski scene, springing full grown out of an isolated Idaho sheep pasture." For years, Sun Valley reigned supreme as America's single world-class ski resort. [40]

The Development of Skiing at Mount Rainier

Among ski enthusiasts, the Paradise area acquired national renown in the 1930s. For a short time, winter sports loomed so large at Mount Rainier that the superintendent described them as the park's most important public use. [41] Mount Rainier's emergence as a major ski area followed fifteen to twenty years of increasing local use of the park for winter recreation.

The Mountaineers began making annual and well-publicized winter pilgrimages to Paradise Valley in 1912. At first these were by snowshoe. Club member Thor Bisgaard, a Norwegian, led some fellow Mountaineers on the first cross-country ski trip to Paradise Valley probably in the winter of 1915 or 1916. This was the earliest known use of skis in Mount Rainier National Park. A group of NPS officials and RNPC board members who called themselves the SOYPs (an acronym that celebrated their penchant for wearing "socks outside your pants" on hiking trips) began making their own annual winter expeditions to Paradise Valley in 1920. In the course of the decade, the SOYPs gradually exchanged snowshoes for skis. At the same time, they became more and more impressed by the possibility of making Paradise a winter sports area. [42]

Beginning in 1923, the NPS kept the park road open to Longmire while the RNPC provided a variety of snowplay activities, rental equipment, and a lunch service at the National Park Inn. At the end of the decade, the RNPC looked to the expansion of winter sports to justify its new investment in Paradise. The NPS received mounting pressure from local booster clubs and winter sports enthusiasts to plow the road all the way to Paradise. In 1930, the park road was kept open to Canyon Rim and two years later it was plowed as far as Narada Falls. Increasing numbers of winter recreationists drove to the end of the road and skied the last few miles to Paradise. [43]

In April 1934, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer sponsored an event at Paradise that definitely put Mount Rainier on the map of national ski competition. The first annual Silver Skis race featured a five-mile course from Camp Muir to Paradise Valley, with an elevation drop of approximately 5,000 feet. Sixty contestents made the arduous trek from the end of the road up the slope of Mount Rainier, then came racing down before a large crowd of spectators. The route was thought to be one of the most challenging in ski competition. Eight months after the race, in December 1934, the National Ski Association voted to use the lower part of the Silver Skis course for the site of its national championship downhill and slalom ski races, to be held the next spring. [44]

This contest attracted more than the usual amount of interest because it also served as the occasion for the Olympic ski team tryouts. The downhill racecourse started at Sugar Loaf at 8,500 feet elevation and descended past Panorama Point into Edith Creek Basin, near the Paradise Inn. The course had an overall pitch of 33 percent. The slalom course was set up on the uphill side of Alta Vista, a prominence above the Paradise Lodge. Sportscasters from the Columbia Broadcasting System provided live coverage for radio listeners throughout the United States, while three wire services described the event for newspapers. Moving-picture photographers documented the contest for newsreels. An estimated 7,500 spectators drove approximately 2,000 automobiles into the park and hiked up to the Paradise meadows to get a view. Tomlinson had the road plowed a mile above Narada Falls to provide extra parking space. It was the busiest weekend in the park's history up to that time. [45]

Second Thoughts

Ever since Mather had singled out Mount Rainier as one national park with the potential to become a significant winter playground, the park administration had striven to encourage more and more winter use. Tomlinson was sensitive to local ski clubs' demands for better access to Paradise Valley; in his view, the large expense of snow removal was the only significant factor to be weighed against it. He had the road plowed as far as Narada Falls during the winter of 1935-36, and kept it open all the way to Paradise in the winter of 1936-37. Meanwhile, he listened sympathetically to the request of the RNPC's manager, Paul Sceva, that the government build an aerial tram from Narada Falls to Paradise for winter visitors, promising to take the matter up with his superiors. [46]

But Tomlinson also admitted that heavy winter use of the park was creating severe administrative challenges. Problems of winter use ranged from the cost of snow removal to inadequate parking and lodging facilities, treatment of ski injuries, avalanche danger, and public pressure for permanent ski lift and aerial tram fixtures that would mar the landscape during the summer season. Moreover, these difficulties were not limited to the Paradise area. Thousands of skiers began driving to the Cayuse Pass area for a day's worth of recreation, and local ski clubs and civic groups from Enumclaw to Seattle started calling for ski facilities at Sunrise, too. [47]

Although Tomlinson did not necessarily share their views, some NPS officials began to question whether downhill skiing was an appropriate activity in a national park. The skiers' growing emphasis on speed, technique, athletic competition, and urban amenities led some park officials to view them as an unwelcome user group. This was perhaps the most controversial aspect of the problem. It called for a subjective judgment on the kind of experience that downhill skiers typically had in the park. Doubts about the appropriateness of this sport in a national park setting were crucial because they undergirded public debate over seemingly more objective winter-use issues, such as snow removal costs and ski lift development.

Mount Rainier's landscape architect, Ernest A. Davidson, argued that the growing popularity of the park as a downhill ski area was insidious, because skiers, as a group, were pushing for developments that would be injurious to the national park's broader purpose of providing for the public's enjoyment of nature. He tried to define the problem objectively this way:

There is a point where a fine healthy outdoor sport begins to degenerate. This point is reached when the majority of its so-called devotees are more interested in the various side-lines of the sport than they are in the sport itself; when the sport becomes the social thing-to-do, rather than the athletic thing to be done; when the results of participation become physically useless or harmful, rather than physically beneficial. At Mt. Rainier this point is dangerously near. [48]

Davidson suggested that the NPS should not plow the road above Narada Falls, nor provide any rope tow or other mechanical lift at Paradise. Then those skiers who wanted a physical challenge would rightly come to the national park, while those who wanted only the thrill of the downhill runs would go elsewhere.

The problem for Tomlinson was that the differences between downhill and cross-country skiing were still fairly subtle in the 1930s. The value judgments defined by Davidson were not widely recognized even by skiers themselves. An account of a day of skiing at Paradise, written in 1938 by a Tacoma high school student named Ralph A. Spencer, illustrates what a fine line Davidson was attempting to draw at that time. [49] To what class of skier did Spencer belong?

"Skiing is like the measles!" Spencer wrote. "I was exposed about three years ago to the most glorious winter sport there is. The craze quickly spread among my friends, just as it is still spreading over the country." With two friends, Spencer would pile skis on top of the car and leave the city at four in the morning for a day at Paradise. The road trip was itself an adventure, with the first intimate view of Mount Rainier never failing to give him a "choked feeling" in his throat. At Narada Falls, the boys would park the car and shoulder their skis and packsacks for the hike up to Paradise.

As we round the last curve there, lying in full view, with welcome smoke pouring from huge chimneys is the gray, rambling lodge of Paradise. At the entrance to the lodge are literally hundreds of skis, stuck in the snow, with the owners in the lodge, where a crowd is gathered about the huge heater, discussing spills and waxes. After a hasty breakfast in the ultra-modern cafeteria, and following a session in the ski-shack with cans of wax, we are ready for the long climb to the face of Panorama...

With canvas climbers attached to the skis we begin the tedious climb to Panorama, with mighty Tatoosh range at our backs. Over the practice hill and up to the saddle of Alta Vista, our course lies. Far down in the valley, like doll's houses on a vast white sheet are the inn, the Sluskin building, the guide houses and the Tatoosh building.

Up from the front of the Sluskin building to the top of Alta Vista runs the modern ski tow, installed just this year. A continuous revolving rope, the lift is an easy and energy-preserving access to the heights above.

At the base of Panorama the tedious, agonizing grind starts up over the face of the field. At the halfway mark the slight mist of snow has become a wind, and as we round the protected side, a breath-snatching gale hits us square in the face. Biting wind and flying snow sting our visor-protected faces and hoods are put on parkas to shut out the cutting cold...

Goggles are adjusted, harnesses secured, climbers removed, and the long-awaited descent begins. Down the face of Panorama, with a snow-tossing stem turn, we are off With stinging wind taking away your breath, pants whipping in the breeze, the terrain zipping away from under you at a terrifying clip, knees bending in the famed Hannes Schneider-Arlberg crouch.

At last the inn comes into sight, and down the draw of Alta Vista we speed. With a screaming cristie at the door, we stop. It's over—a long time to climb up, a few minutes to speed down...

Did Spencer revel primarily in the physical challenge and the outdoor experience, or the athletic comradery and the thrill of the downhill run? Was he the type of park user who would be glad to see the rope tow removed, or would he then take his skis elsewhere? Spencer's story is significant because it reflects the sport of skiing at a time of transition when it was difficult to evaluate. This ambiguity in the very nature of skiing was the source of the Park Services s indecision over winter use during the 1930s.

By the winter of 1937-38, Paradise was the leading ski resort in the Pacific Northwest. The NPS permitted the installation of a rope tow at Paradise during the winter of 1937-38. Powered by an eight-cylinder Ford engine, the rope tow could haul 250 skiers per hour from the guide house to the saddle of Alta Vista. Enterprising skiers extended the length of the downhill run all the way to Narada Falls, where they caught a company shuttle bus back up to the foot of the rope tow. Floodlights were installed to allow night skiing, and the Paradise Inn rented out rooms through the winter season. The RNPC employed Austrian expert Otto Lang as a ski instructor. Classes were conducted daily throughout the winter. [50]

The park administration balked at other proposed developments. Tomlinson tried unavailingly to persuade officials of the Washington State Highway Department to close the state road up to Cayuse Pass during the winter, arguing that there was too much avalanche danger. The superintendent urged The Mountaineers not to advertise an organized ski outing to the Tipsoo Lakes country, above Cayuse Pass, suggesting that once the area was discovered the NPS would be hard-pressed to develop shelters and sanitary facilities for the winter crowds. [51] When an estimated 34,000 people used the Cayuse Pass area for skiing during the winter of 1937-38, Tomlinson tried to get the Enumclaw Ski Club to provide a ski patrol, but refused to commit any of his own staff to this area. For several seasons in a row, the NPS withstood pressure from the Pacific Northwest Ski Association and various local ski clubs to build a modern ski lift from Paradise to Panorama Point. The NPS permitted the annual Silver Skis competition to take place again in 1936 and 1938-41, but with a minimum of fanfare. The NPS refused all requests to hold additional contests at Paradise, asserting that the fireworks displays and carnival-like atmosphere normally associated with these meets were not appropriate in a national park. [52]

Still another aspect of the ski season that troubled park administrators was the tendency toward "boisterousness and excessive drinking" by young people at Paradise Inn. [53] The superintendent complained to General Manager Sceva that the sale of beer in the fountain room made the Paradise Inn "similar to any common roadside tavern," and he recommended to his superiors in Washington that no alcoholic beverages should be served in the new government-owned ski lodge building that was then nearing completion. Associate Director Arthur E. Demaray approved this request a month before the building opened, in November 1941. [54]

|

| Skiers at Paradise in 1941, the busiest downhill ski season in the park's history. (Photo courtesy of Mount Rainier National Park.) |

A Policy in Transition

By the end of this period, park officials were wondering whether the effort to develop a winter season in Mount Rainier had been too successful. Winter use grew faster than anyone anticipated, outpacing the growth in visitor use overall. Winter use, defined for statistical purposes as the number of people who entered the park during the six-month period of November through April, accounted for five percent of the park's total visitation in 1923 (i.e. November 1922 through April 1923) and climbed to thirty-eight percent by 1941. The most rapid growth came at the end of the 1930s.

Yet, if park officials had begun to lean toward a more conservative winter-use policy on the eve of the Second World War, they left it to the next superintendent and NPS director to persuade Washington residents of the need for such a change of direction. At the end of this period, the NPS made two significant concessions to skiers which seemed to confirm Mount Rainier as a major ski area in the minds of local skiers. In 1938, Director Cammerer approved plans for a large dormitory building at Paradise, to be constructed from CCC, PWA, and regular appropriation funds. The tentative plan for this building was to use it for NPS or RNPC employee housing during the summer, and to lease the building at cost to the RNPC for use as a low-rate guest facility during the winter. Known as the Ski Lodge, the building was designed with four main compartments, each with lobby, toilet, shower, and dormitory area. It would accommodate 80 people. The hope was that low-income people, semi-charitable groups, and college and high school students could be accommodated for about 75 cents per person per night. [55] The Ski Lodge was finally completed in December 1941, the same month that the United States entered World War II. As the war years brought a hiatus to winter use of Mount Rainier, the future use of this building was unclear.

The second significant concession to ski groups was Director Newton B. Drury's decision, approved by the Secretary of the Interior on December 12, 1940, to permit the installation of a demountable, T-bar type of ski lift. [56] The T-bar represented an intermediate-sized lift between the rope tow and the chair lift. The plan was to extend the lift well beyond Alta Vista to the foot of Panorama Point. The Pacific Northwest Ski Association had been calling for a chair lift for the past three years. In view of the later controversy over the construction of a permanent chair lift in the park, this was an unfortunate precedent. In June 1941, the RNPC announced that it was not prepared financially to build such a lift, but this only postponed the issue until after World War II. [57]

THE OHANAPECOSH HOT SPRINGS COMPANY

The large addition to Mount Rainier National Park in January 1931 brought the natural feature known as Ohanapecosh Hot Springs under the jurisdiction of the park administration. The feature consisted of more than a dozen separate springs, some of them very hot, which drained into the Ohanapecosh River, deep in the lowland forest in what was now the southeast corner of the park. At that time the springs could be reached most easily from the town of Lewis (Packwood), Lewis County, at the end of a twelve-mile mountain road. Alternatively, the springs were sixteen miles by trail from Narada Falls. The springs were locally popular as a place to camp and bathe, attracting a few thousand visitors each year.

Early Interest in the Springs

The park administration had shown an interest in the Ohanapecosh Hot Springs long before the boundary extension in 1931. Park superintendents made repeated proposals—in 1913, 1916, 1919, and 1925-26—to extend the park boundary so as to include this area in the park. The original boundary of 1899 placed the hot springs a mere fifth of a mile outside the park. The ostensible reason for including the springs in the park was to give protection to the natural feature itself, but the overriding concern was to be able to control visitor access and use in the southeast corner of the park. As long as the springs remained just outside, it would be an easy thing for Lewis County residents to camp at the springs and hike across the park boundary—either intentionally or inadvertently—to hunt game. But each time the proposal for a boundary change surfaced, it ran into opposition from Lewis County residents and local developers. These opponents of the boundary extension claimed that the NPS was merely acting in the interests of the RNPC, which wanted to stifle development of the springs and protect its monopoly in the area. [58]

When the springs finally came under park administration in 1931, development of the springs already dated back many years (Chapter VIII). The earliest commercial tent camp at the springs was established by Mrs. R.M. O'Neal in 1913. Apparently it was a short-lived affair. [59] Three years later, Superintendent Reaburn noted that many people attributed therapeutic powers to the springs, but that "very little development work has been done on them." [60] In 1921, a local entrepreneur named N.D. Tower obtained a permit from the Forest Service to develop a resort at the springs. Tower's permit contained a 25 year lease. After a few years, Tower found an investor by the name of Dr. Albert W. Bridge and together they formed the Ohanapecosh Hot Springs Company. Bridge was owner of the Bridge Clinic in Tacoma. In the spring of 1924, Bridge and Tower hired a road crew to construct five and a half miles of road from Clear Fork to the hot springs, and that summer they opened a tent camp and a few cabins. In 1925, they built a small hotel and two bathhouses. According to an announcement in the Tacoma Ledger, the cedar-shake and log building was supposed to be a start toward "a great resort and sanitarium" which would acquire a national reputation "such as the Hot Springs in Arkansas." [61] Asahel Curtis offered a more realistic appraisal when he predicted to Superintendent Tomlinson that the development would "never amount to anything" unless a large company got involved. [62]

Park officials were unsure how to handle the Ohanapecosh concession when they inherited it from the Forest Service in 1931. It was clear that the Ohanapecosh development would remain small compared to the RNPC's developments at Paradise, Longmire, and Sunrise. The RNPC refused to have anything to do with it. Even the owner, Dr. Bridge, who bought out Tower's share in the company in the mid-1920s, seemed to be biding his time until the Eastside Road was completed. [63]

To make the situation still more problematic, local opinion about the concession was divided. The developers claimed to have strong local support for their enterprise, which they styled as a populist franchise challenging the monopolistic RNPC, whose profits they alleged were siphoned off by Seattle and Tacoma capitalists without any benefit to the people of Lewis County. But many people who actually used the springs did not appreciate the Ohanapecosh Hot Springs Company. They thought the government should provide campground, toilet, and bathhouse facilities for free rather than allow a concession to charge a fee for them. With the opening of the road to the springs in 1925, a considerable number of people with rheumatism and other maladies had started coming to the springs each summer, camping in a free public campground provided by the Forest Service, staying for weeks or months at a time, and paying the company twenty-five cents per day for use of its bathhouse and concrete-lined hot pools. These convalescents formed a summer community of as many as 135 people, all of whom favored free public access to the springs. [64]

In the early years of the Depression, Tomlinson showed some sympathy for these campers, even though they were not the typical kind of park visitor. He refused to let the concessioner build new cabins in the area of the free camp sites, even though this area was too hummocky for a good campground, because it would require moving the campers farther away from the springs. Tomlinson explained to Bridge and his architect that this was undesirable "due to the fact that many of the campers are crippled with rheumatism and other diseases and want to have their camps as close as possible to the bath house." Moreover, Tomlinson wanted the company to provide two classes of baths with one at a lower rate "to meet the demands of poor people who claim they cannot afford even to pay that much, but feel that the Government should provide free bathing service." [65] On the other hand, Tomlinson showed no inclination for the NPS to take over this service from the concession.

A Second Park Concession

As a result of all these circumstances, the boundary addition in 1931 brought a second concession into the park which did not fit the mold of the NPS concession policy established under Mather. The Ohanapecosh Hot Springs Company was a throwback to the type of rustic resort hotel such as James Longmire had built. It was also akin to the small, family-owned resorts that began appearing along highways and lakeshores in the national forests in this era. NPS planners disparagingly referred to such developments as "topsy" because of the disorderly or topsy-turvy way that the buildings and grounds usually developed.

|

| The Ohanapecosh Lodge was built in 1925 and became a secondary park concession after the Ohanapecosh area was added to the park in 1931. It was removed in the early 1960s. (Photo courtesy of University of Washington.) |

This is not to say that the Ohanapecosh development was ignored by the Park Service's landscape architects and engineers. Rather, the concession s small size limited how much could be done with it. The concession was permitted to continue operating with a minimum of improvements to the existing facilities. A sawmill was removed in 1934, and an oil house was taken out in 1938, but other improvements to the site were postponed until the Eastside Road neared completion. [66] In 1939, the Ohanapecosh Hot Springs Company added five new cabins to the existing twenty, improved the employee quarters in the lodge, and built a five-car garage. In 1941, the company completed seven more cabins. [67] Despite these improvements, however, the development remained substandard. It would be a growing embarrassment to the park administration until its closure in 1960.

THE ORDEAL OF THE RAINIER NATIONAL PARK COMPANY

The partnership of public and private investment which had underpinned the development of Mount Rainier National Park in the 1920s was superseded by a matrix of federal relief programs in the 1930s. The Seattle and Tacoma businessmen who served on the board of directors of the RNPC saw their influence ebb rapidly as NPS officials concerned themselves less with private capital and more with the federal administrators who held the purse strings of the Emergency Conservation Work (ECW), Public Works Administration (PWA), Civil Works Administration (CWA), Emergency Relief Administration (ERA), and other New Deal agencies.

The RNPC's stockholders, meanwhile, found their hopes for a large return on their investment blighted by the Depression. As the company's outlook changed, they began to wonder how they could tactfully extricate themselves from such a public-spirited yet unprofitable venture. The financial misfortunes of the RNPC held longterm consequences for the park, because twenty years later it would become necessary for the federal government to buy the company's buildings and lease them back to the RNPC in order to keep the concession operational. Therefore, the nature and finances of this company are significant to the park's administrative history.

Reversal of Fortune

Company spokespersons insisted that the progressive-minded businessmen and women of the Puget Sound region who had launched the RNPC had done so with little thought of private gain; rather, they had responded to Mather's summons to develop the national park for the economic return it would bring to the region. These spokespersons pointed out that the company's elected officers served without compensation, and that the stockholders had thus far received negligible dividends as most of the RNPC's profits were plowed back into the expanding enterprise during the 1920s. [68] But the RNPC was comprised of longterm investors. The company's financial records show that it posted strong yearly profits as total revenues climbed impressively from 1916 to 1929. There should be little doubt that the RNPC management was motivated by considerations of profit and loss just like the management of any other company.

The effects of the Depression on the RNPC were profound. During the worst years of the Depression the RNPC's gross revenues shriveled to about one quarter of what they had been in 1929. In six out of ten years of the Depression decade the company lost money. In 1933, the company's indebtedness was so severe that it was barely able to scrounge together enough capital to open for business that summer. The Depression was all the more stunning to company officials because the preceding decade had been so full of promise. For the whole 1920-29 period, the RNPC averaged an annual gross revenue of $437,000 with a net profit of approximately 17 percent. Stockholders were told that when all the approach roads to the park were completed, the company's business would quadruple. [69] As it turned out, the 1920s were the RNPC's heyday. The company would suffer further financial reverses during the war years and again in the early 1950s. It would never approach the level of business that its founders had anticipated. After grossing more than a half million dollars in 1925, it would not pass that mark again until the late 1950s. In a sense, the Depression delivered a blow from which the company never recovered.

But the company's problems went deeper than that. They also had to do with changing visitor demand. As discussed in Chapter IX, the RNPC was asked to undertake an ambitious five year development plan in 1928. The commercial tent camp at Paradise was to be upgraded to housekeeping cabins at the same time that a new, first-class hotel was to be built near Nisqually Vista. In addition, the company agreed to undertake another major development at Sunrise. To finance this $2.5 million scheme, the RNPC tried to enlist the four transcontinental railroads serving the Pacific Northwest. When that failed, the company scaled back its five year development plan to something that could be financed by local capital. The RNPC was stretched thin trying to modernize its accommodations at the very time that the economy crumbled. [70]

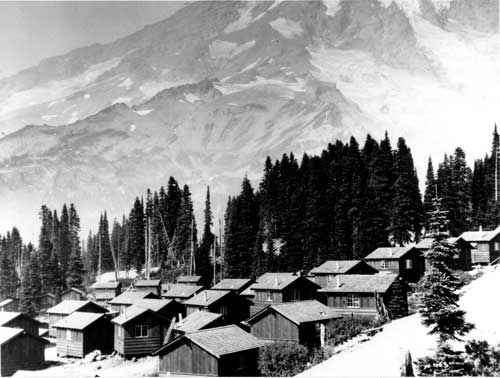

|

| The concessioner built more than 400 cabins at Paradise and Sunrise in the early 1930s. They were not popular with visitors and did not stand up well under the heavy snowloads. Removed in 1944, they left lasting impressions in the meadows. (Photo courtesy of Mount Rainier National Park.) |

After borrowing heavily to pay for new lodges and cabins at Paradise and Sunrise, the RNPC was some $375,000 in debt. The company tried to increase its stock but could find no new subscribers as the business climate worsened. Desperate for cash, the company tried to borrow $350,000 through an issue of $500 notes that would mature at six percent in five years. [71] The RNPC's new president, Alexander Baillie, urged the four railroads to subscribe to 1,000 notes apiece. NPS Director Albright wrote to the president of the Northern Pacific, Charles Donnelly, asking that his railroad loan $200,000 to the RNPC. After months of haggling, the four railroads finally tried to appease the RNPC and the Park Service with token loans of $2,000 apiece. Altogether, the RNPC raised a mere $30,000 in notes. In 1933, the RNPC appealed to Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes for a loan from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), but since a large part of the money was needed to retire the company's debts the RFC could not help out. [72]

Meanwhile, the company was faced with shrinking business revenues. Brand new housekeeping cabins stood empty through the summer; a newly redecorated and refurnished Paradise Inn experienced room vacancies on weekends in July; waitresses and busboys stood around with nothing to do in the inn's elegant dining room. The RNPC's account books were awash in red ink: a $69,000 loss in 1931, $91,000 in 1932, $73,000 in 1933. Superintendent Tomlinson could do little more than offer the company praise and encouragement. He wrote in his annual report of 1931:

The improvements and new equipment provided by the Public Utility Operator during a time of serious business depression throughout the country are indicative of the progressive attitude of Company officials. Although business was far below expectations, the impression gained by visitors as to the fine accommodations now available places the company in an excellent position to meet the needs of visitors when conditions return to normal. There were more expressions of approval of the Operator's facilities this year than during any other year, and I desire to here acknowledge my personal appreciation of the fine spirit of cooperation shown by directing officials of the Rainier National Park Company. [73]

Mitigative Measures

The company looked for ways to cut operating expenses. Transportation service between Seattle, Tacoma, and Portland and the park was turned over to the North Coast Transportation Company in 1931. That company had fully-enclosed, 32-passenger busses. Passengers transferred from the large busses to the RNPC's open-air, 14-passenger stages at Longmire. Tomlinson considered this arrangement an improvement because the large busses were more comfortable for the long drive while the stages gave passengers a better view of the scenery from Longmire to Paradise. [74]

The company proposed to sell to the government its hydroelectric plant on the Paradise River. [75] This proposal took the form of a bill, which Washington's Senator Wesley Jones introduced in the Senate on December 14, 1931 [76] At the annual meeting of the board of directors in January 1932, it was suggested that the Seattle and Tacoma chambers of commerce be requested to lobby for the bill through their representatives in Washington, D.C. Albright also supported the proposal. In a memorandum written for the Secretary of the Interior, Albright explained that the company had used the majority of the electrical power supply when the plant was built in 1915. Now with the lighted public campground and numerous administrative and residential buildings at Longmire, the situation was reversed, with the government using most of the plant's power-generating capacity. Albright informed Secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur that it was the government's policy to own such power plants in the national parks, and moreover, the purchase would provide the company with much-needed capital. [77] This bill failed to pass.

In August 1932, General Manager Sceva and RNPC President Baillie wrote to the Secretary of the Interior to request a waiver of the $2,000 annual franchise fee. "We rather feel we are partners of the Government in maintaining these facilities for the comfort and convenience of visitors," Baillie wrote. "I am not using idle words when I say that if this charge is not eliminated from our contract it will be impossible to raise money from the public to create increased facilities." [78] This request was politely refused. Assistant Secretary Joseph M. Dixon reminded Baillie that the RNPC had been allowed a smaller franchise fee than the Curry Company of Yosemite when the RNPC's new contract was negotiated in 1928. [79]

Company officials had to adjust their expectations for the new development at Sunrise. Even after the plan for the Sunrise Lodge was scaled down from the original plan of a large, deluxe hotel, it was opened in July 1931 with some $50,000 of interior finishing yet to be completed. The new building contained a cafeteria-style food service, baths, supply store, post office, and employee quarters, but no guest rooms. Uphill from the lodge were 215 housekeeping cabins.

To attract business to this new development the RNPC began marketing the Sunrise development as a dude ranch. The company brochure stated, "Memories of the Old West are revived and experienced in the Sunrise Dude Ranch where real western riders entertain and lead you on many interesting trips." Yakima Park was billed as a former cattle range abounding in "romantic legends." The Mount Rainier Mining Company's idle works in Glacier Basin were styled the "Ghost Gold Mine" and were the destination of moonlit horseback rides. A small box canyon called Devil's Hole was claimed to have been a hideout for rustlers, where two badmen were said to have defended themselves against an attack by a large posse of local townsmen. [80] This kind of exploitation of the national park was not in keeping with the purpose of the park concession, but under the circumstances park officials did not object to it. Indeed, the design theme of the new administrative buildings at Sunrise, which commemorated the Indian past in Yakima Park by the use of a dubious frontier-blockhouse architectural style, only contributed to the hype.

An important thrust of the RNPC's new marketing effort at Sunrise was its offering of a weekly rate that included cabin, meals, and a horse, all in one package. The aim, once again, was to attract easterners to Mount Rainier. The RNPC also coordinated its publicity and sales efforts with the transcontinental railroads, offering all-expense fares that included two and three days' accommodations at Mount Rainier in the cost of a railroad ticket. These tickets could be purchased at any railroad office or travel agency in the United States and Canada. Beginning in 1932, RNPC officials persuaded the Seattle, Tacoma, and Yakima chambers of commerce to help pay the cost of the company's promotional literature. [81]

Meanwhile, on the south side of the mountain, the company adjusted its rates and schedules to appeal to a local clientele. During the 1933 season the guide service at Paradise was greatly curtailed, the photograph business was not opened, and most guest services were concentrated at the Paradise Lodge, the inn being used only for overflow guests on weekends. These drastic measures lasted just one season, and succeeded in trimming the company's losses from what they had been the year before despite the fact that park visitation fell to its lowest point during the whole Depression.

Government Purchase of the Longmire Tract

Park administrators had been urging that the government purchase the Longmire Springs property since the early years of the national park. The privately-owned tract, or inholding, flew in the face of the basic national park concept of public ownership of the land. The more cluttered the Longmire property became, the more it undermined the purposes of the national park. Indeed, a case could be made that the old Longmire Springs Hotel was an example of the very kind of unsightly development that Cornelius Hedges and his companions had had in mind during their legendary discussion beside the Madison River in Yellowstone when they pledged themselves to work for the creation of the nation's first national park. It is rather surprising, given the centrality of public ownership to the national park idea, that Congress was so reluctant to appropriate funds for the purchase of inholdings like the Longmire property.

In 1927, Congress finally appropriated $50,000 for purchases of private lands in national parks, with the stipulation that fifty percent of each purchase must come from private donations. That year Mather approached the RNPC about buying the Longmire property, based on a fifty-fifty split and a $30,000 option price. The RNPC countered that it would donate $15,000 if the government would remit its $2,000 franchise fee yearly until the company was reimbursed. This was unsatisfactory to Mather and the matter was allowed to rest. [82]

Six years later, the RNPC's president, Alexander Baillie, reopened the issue with Director Cammerer, suggesting that the property owners themselves might be willing to make a donation. "I think it would not be difficult to get the Longmire Mineral Springs Company to put a reasonable price on their property and then cut the price in two, which I understand is the usual procedure where the National Park Service is acquiring property in or adjoining the National Parks," Baillie wrote. The owners placed a value of $100,000 on the land, and would likely accept $50,000 from the government, he thought. [83] At this stage it was difficult to judge whether Baillie was motivated by concerns about adverse use of the land or by a desire for personal gain: he neglected to mention that the Longmire Mineral Springs Company had bought the land from the Longmire family for about $60,000, and that his wife was a 25 percent owner in that company. In any case, Assistant Director Arthur E. Demaray rejected the $100,000 value as unrealistic. [84]

One year later, in 1934, Cammerer received a communication directly from the Longmire Mineral Springs Company's president, a Tacoma lumberman named Frost Snyder. Cammerer was willing to deal if the property was reappraised. Nearly a year later, Tomlinson reported to the director that he and Snyder had been able to settle—"after considerable delay, numerous conferences, and much investigation"—on an appraisal of $55,000. Evidently both the Longmire Mineral Springs Company and the RNPC hoped that the other would donate half the purchase price, and negotiations stalled once more. In 1936, the RNPC tried to have the property reappraised at $100,000, expecting the owners to settle on a basis of $50,000. [85]

These protracted negotiations reached a critical stage in 1937. With the RNPC's 20-year lease soon to expire, Cammerer and Baillie both displayed less and less patience with one another. Baillie urged the NPS to secure an emergency appropriation that would allow it to pay 100% of the option price. Cammerer reiterated his request that the RNPC contribute half, noting that the Curry Company had made an analogous donation for the purchase of the Wawona properties in Yosemite. [86] Baillie did not even acknowledge the director's request, but coolly replied:

I may tell you that the public are very much aroused over the possibility of the Longmire Mineral Springs property falling into the hands of a resort crowd and there is much criticism of the National Park Service for not acquiring the property at its appraised value when you had the opportunity to do so. And I think if you have another appraisal of it the price will be more than doubled. And with no restrictions as to what could be placed on the property except the restrictions of the State, one can't foresee what may happen.

Does Mr. Ickes understand the situation? [87]

It was well-known that Cammerer had an uncomfortable relationship with the irascible Secretary of the Interior, and Baillie's final remark was clearly barbed. Cammerer duly instructed his assistant director, G.A. Moskey, to review the now-voluminous file on the Longmire property and prepare a memorandum. In late October, Cammerer and Tomlinson discussed the Longmire property with Baillie and Paul Sceva in person at the Rainier Club in Seattle. Now it was Cammerer's turn to bait Baillie: he wondered aloud whether the RNPC president was acting primarily in the interest of his wife's 25 percent share in the Longmire Mineral Springs Company? Baillie resented this, but the men nevertheless reached an agreement. The property was assessed at $60,000, and Cammerer promised to seek a special appropriation by Congress for the government's share of $30,000, while Baillie promised to urge the Longmire Mineral Springs Company to grant the U.S. government a one-year option to purchase. [88]

The RNPC's general manager, Paul Sceva, believed that the deal was still very tenuous. He contacted local conservation groups, chambers of commerce, and Representatives John M. Coffee and Charles H. Leavy of Washington in an effort to create public support for the deal. [89] Sceva's letter to J.J. Underwood, the Seattle Chamber of Commerce's lobbyist in Washington, D.C., suggests how serious the situation had become:

...The owners of the property, the Longmire Mineral Springs Company, with Mr. Frost Snyder, of Tacoma, as its President, has [sic] determined to get some revenue from this area and has offered it for sale in whole or in part. The area can easily be divided into one hundred lots that would readily sell to the public at a price from $1,000 to $2,000 per lot. I am of the opinion that the whole area could be sold within ninety days and undoubtedly bring the owners from $110,000 to to [sic] $120,000 by such means.

Fortunately, Mr. Alexander Baillie's wife owns 24% of the stock of the Longmire Mineral Springs Company. She is a public spirited woman and a lover of National Parks, and through her influence she has been able to talk down the aggressiveness of Mr. Snyder in his method of selling this area without giving the National Park Service an opportunity to buy it. Furthermore, she has been able to have that company grant to the National Park Service an opportunity to buy for one year from this date at a price of $60,000. I understand the Longmire Mineral Springs Company paid approximately $60,000 for this area years and years ago.

If the National Park Service is unable to exercise the option and purchase the area, the method referred to above of selling will undoubtedly come to pass and then we will have virtually a Coney Island right in the center of Mount Rainier National Park. To my personal knowledge, I know of one man who offered $2,000 for a plot of this area fifty by seventy. He wanted to install a beer tavern. I know of another one who offered $2,000 for a small area around the soda springs and he intends, if he is successful in his purchase, to build a tavern with the soda spring in the middle of it, using the soda spring water for a soda fountain and other uses. The warm springs would probably be utilized for bath houses. Undoubtedly there will be gas stations, repair shops, curio stands, hot dog stands, dance halls and everything imaginable, because the general public believes there are great profits to be made in individual business in the Park. I am of the opinion that any purchaser of any of these lots could make a very good living out of his endeavor because he would not be burdened with any expense of publicity, promotion fees or whatnot. The purchasers would merely tie on to the tail of the kite of the Rainier National Park Company and pick off any business that they could get from the two or three hundred thousand people who go right through this area every year.... [90]

Finally, by the Act of March 9, 1938, Congress appropriated $30,000 for the purchase of the Longmire property. [91] More than a year later, on June 15, 1939, Tomlinson notified Cammerer that Check No. 5,683,886 had been received and delivered to Snyder's partner, C.L. Dickson, treasurer of the Longmire Mineral Springs Company. Tomlinson concluded his message, "Custody of the land and responsibility for its protection and maintenance was accepted today by the National Park Service." [92]

The perilously long delay in acquiring this land may be attributable in part to the attitude of Secretary Ickes. In his "Secret Diary," Ickes fretted about the way the NPS acquired land parcels like the one in Mount Rainier. According to Ickes, park officials would employ an appraiser who "would determine the value of the property to be purchased, then double that value on the basis of an understanding with the owner that half of the doubled value would represent a contribution to the National Government." As a result, alleged Ickes, "the Government would be paying the full, fair and reasonable values of the property instead of fifty percent of it." [93] The official record suggests that Ickes's suspicion was in this case unfounded.

Disappointment with the Winter Season

Mount Rainier's winter season was like a gambling habit for the RNPC: year after year the company officers ruefully tabulated the RNPC's losses during the past winter's operation and then talked themselves into trying it again. The Paradise Inn was available for use and the snow conditions were superb; it stood to reason that the company would do well to extend its operation through the winter. Unfortunately, local skiers did not spend a lot of money while they were in the park, and profits eluded the RNPC. [94]

The company liked to blame the Park Service for making it offer services to the public which were unprofitable, but the fact was that RNPC officials consistently pushed for a winter season, first at Longmire and later at Paradise. They believed that the national park must establish a market; a profitable level of business would develop in due course. The construction of the Paradise Lodge went forward with high hopes of developing a big winter season at Paradise. When winter business failed to materialize, company officials decided that a promotional campaign was required. The RNPC advertised winter sports in Mount Rainier. [95] It leased housekeeping cabins and rooms in the Paradise Lodge for the entire winter season for nominal rates of $30 to $60. The plan was inaugurated for the winter of 1933-34. Superintendent Tomlinson gave it his full support. "This policy of low cost accommodations and the maintenance of a winter road to within 1-1/4 mile of Paradise Lodge are doing more than anything else to increase interest in winter sports in the Park," he wrote in his annual report. [96]

By the end of the 1930s, RNPC officials were feeling discouraged about the winter season. Probably Sceva or someone else with a close involvement in the company was responsible for an editorial in the Tacoma News Tribune, on November 28, 1938, which blamed the government for the RNPC's troubles. "Years ago the government called on the citizens of Tacoma and Seattle to help in the building of a recreation resort at the mountain," the editorial began. Now the federal government was investing heavily in recreation areas, creating unfair competition. Timberline Lodge on Oregon's Mount Hood was the most flagrant example; ski resorts built by government-subsidized railroads were another. At Mount Rainier, meanwhile, the RNPC had incurred a debt of more than $300,000; its old buildings were in need of rehabilitation. [97] The sense of betrayal in this editorial probably reflected the views of the company. The company's president, Alex Baillie, confided to a business associate, "Between you and me and the gatepost, I have been pretty much disgusted with the attitude of the National Park Service in regard to our problems, and while I am optimistic about the future of the Rainier National Park, we don't get very much help from the 'powers that be' in Washington." [98 ] Company officials were in no mood to cooperate with the Park Service on a winter use policy.

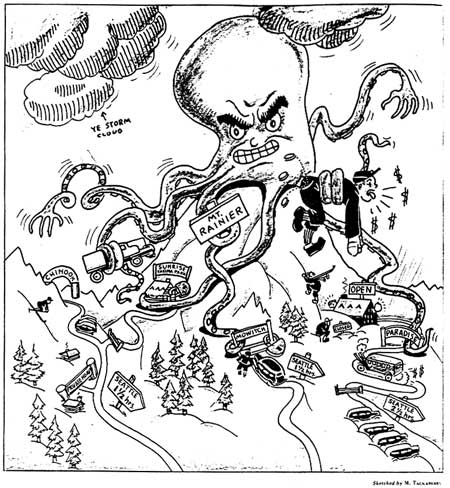

|

| Many Washington residents resented the Rainier National Park Company's monopoly in the park. Here the company is depicted as an octopus barring all access roads to the mountain except the road to Paradise. (M. Tackaberry cartoon from the Washington Sportsman, vol.3 no.9, November 1937.) |

After World War II, Washington residents who wanted skiing facilities at Mount Rainier would demand that the concession either provide this public need or step aside so others could do so. These promoters would attack the NPS for coddling the RNPC and perpetuating a private monopoly that they alleged was against the public interest, a charge that had not been heard since the early 1920s. After the war there would also be a whole new cast of characters: John Preston replaced Tomlinson as superintendent in 1941; Newton B. Drury became the next director of the NPS after Cammerer's retirement in 1940; Paul Sceva would become president of the RNPC after Baillie's death in 1949; and the editor of The Washington Motorist, Roger Freeman, would emerge as the Puget Sound region's most voluble booster after Asahel Curtis died in 1941. Yet, as this issue swelled into the dominant management concern in Mount Rainier National Park in the postwar period, its roots could be found in the 1930s, when Pacific Northwesterners discovered the sport of downhill skiing and the RNPC discovered the vagaries of the winter tourist season.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap10.htm

Last Updated: 24-Jul-2000