|

MOUNT RAINIER

Wonderland An Administrative History of Mount Rainier National Park |

|

| PART THREE: YEARS OF PROMISE, 1915-1930 |

IX. THE RAINIER NATIONAL PARK COMPANY

INTRODUCTION

With the advent of Stephen T. Mather's administration of the national parks, all tourist services in Mount Rainier National Park were consolidated under a single operator, the Rainier National Park Company (RNPC). From its construction of the Paradise Inn in 1916 until its close coordination with the NPS in the development of the Sunrise area fifteen years later, the RNPC played a prominent role in shaping the park.

Many people thought it was too prominent. Some critics argued that the RNPC's exclusive franchise, or "regulated monopoly," was a corruption of the free enterprise system, and that the field should be thrown open to other entrepreneurs. Others charged that the company was leading the NPS toward overdevelopment of the park. Still others claimed that the company and the NPS were developing the park only for the well-to-do. A political cartoon depicted the RNPC as an octopus sitting astride the summit of Mount Rainier, its tentacles splayed down the mountain's flanks in place of the mountain's glaciers.

The RNPC, however, was not without problems during this era. Despite an eight-fold increase in the park's annual visitation between 1916 and 1930, the evolving pattern of visitation gave company officers little else to cheer about. It was frustratingly concentrated on weekends in July, August and September. This made it difficult to keep a resident hotel staff consistently busy during the summer, much less stretch the season of operation very far beyond those three months of the year. The RNPC had to close down and leave its buildings empty for the better part of each year. Most difficult of all from the company's standpoint was the fact that visitors to Mount Rainier overwhelmingly came by automobile from Seattle and Tacoma and either returned home the same day or car-camped, giving the RNPC little or no business. The dearth of out-of-state hotel visitors made it difficult for the RNPC to interest the transcontinental railroads in any joint promotional effort. The RNPC proposed various schemes to increase the number of out-of-state sojourners, from building a golf course at Paradise to teaming up with the railroads in the development of two grand hotels at Spray Park and Yakima Park. In its most controversial move, it proposed to build an aerial tram from the Nisqually Road bridge up to Paradise so that the area could be developed as a winter resort, thereby extending the RNPC's short season of business.

This chapter examines the Park Service's new concession policy and the role that the RNPC made for itself prior to the Great Depression. The chapter is in three sections. The first section concerns the formation of the company and the consolidation of visitor services under a single operator. The second section considers the various challenges to the NPS 's new concession policy in Mount Rainier. The third section traces the RNPC's expansion of facilities and services in the 1 920s as it sought to attract more out-of-state visitors.

THE FORMATION OF THE RAINIER NATIONAL PARK COMPANY

In the summer of 1915, national park promoters across the nation learned that they had a new leader in Stephen T. Mather, "The National Parks Man." Appointed by Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane to reorganize park administration and to drum up support for a National Park Service, Mather threw himself into the work with a will. After his famous gathering of sympathetic publishers and civic leaders in an outing in California's High Sierra in July—an important catalyst in the culminating effort to get a National Park Service established—Mather repeated this strategy on a more parochial scale in Mount Rainier National Park in August. He conducted an eighty-five mile pack trip around the Wonderland Trail with members of the Seattle-Tacoma Rainier National Park Committee and other selected commercial leaders of the two cities. Mather's biographer, Robert Shankland, described the consequences:

They circled the west side by trail, an exciting maneuver, and camped one night at Spray Park, well under Mount Rainier on the north side, between two of its greatest glaciers, Carbon and North Mowich. There, beneath a brilliant full moon, Asahel Curtis, the Northwest's leading photographer, brother of the famous photographer of Indians Edward S. Curtis, mesmerized the company with a recitation of Robert W. Service's The Spell of the Yukon. Next day they crossed Carbon on foot and left the park at its northwest corner. Then in earnest conclave at the Rainier Club in Seattle, Mather worked his miracle: he talked the Seattle and Tacoma crowd—T.H. Martin, Chester Thorne, H.A. Rhodes, Alex Baillie, William Jones, S.A. Perkins, David Whitcomb, Joseph Blethen, Everett Griggs, J.B. Terns, Herman Chapin, Samuel Hill, C.D. Stimson—into getting together in a Rainier National Park Company and building an inn in Paradise Valley. [1]

Not surprisingly, the Rainier National Park Company maintained a different version of these events in which the original vision of a Paradise Inn belonged not to Mather but the company's first general manager, T.H. Martin. For five years, the story went, Martin contemplated the mountain through the windows of the Tacoma Building where he worked as secretary of the Tacoma Commercial Club and Chamber of Commerce. What the city needed, Martin believed, was a first-class hotel on Mount Rainier "in order to entice persons of real vision and financial stature" to visit the Pacific Northwest "and perhaps consider the commercial possibilities in this Great Empire." Martin resigned his post in 1915 to devote his full energies to this plan. According to the company history, the decisive meeting occurred not at the Rainier Club with Mather but in Tacoma on October 3, 1915. There, Martin persuaded a handful of businessmen to try and bring Seattle and Tacoma financiers together to form a company which would handle all hotels, camps, and transportation in the park. Promptly, the group dispatched Martin to San Francisco to present his proposal to Mather. [2]

The discrepancy between these two stories is instructive. The difference between them goes deeper than whether Mather or Martin—the national or local figure, the public official or the capitalist—comes out the hero. It has been said that the Park Service's dilemma in managing the national parks for both preservation and use is compounded by the tension between two fundamentally different conceptions of what parks are for. One conception would have them managed respectfully as "artifacts of culture." The other would have them managed exploitively as "commodity resources." [3] The roots of this problem run deep. Clearly, Martin and the other businessmen who formed the Rainier National Park Company were interested in profits. But they were also motivated by the prospect of making Mount Rainier National Park into a nationally-renowned asset of the Pacific Northwest and a magnet for regional growth. Their vision harkened back to the Seattle and Tacoma boosters of the 1890s and early 1900s who sought to identify their respective cities with the mountain's appealing image, to "package" the Pacific Northwest as a place that offered an exceptional quality of life. For all of their veneration of the mountain, it represented to them a commodity resource.

Mather, for his part, wanted to make the scenic beauty of Mount Rainier accessible to all the people. This would pay dividends of another sort. Mather's long-term goal was to introduce enough Americans to the national parks to create a strong political commitment to the national park idea so that the parks would be duly preserved for future generations. Mather's grand vision was to make the national park system into one of America's most celebrated institutions. In other words, he wanted to secure each national park's place in American life as an artifact of culture. At this point in time, in 1915-16, the interests of the Seattle and Tacoma businessmen converged perfectly with Mather's strategy of national park preservation. But the tension between their ideals was inherent in the compact.

Mather had no illusions about the Park Service's alliance with business. In several national parks, the Department of the Interior had already forged such an alliance with one railroad or another. In Glacier, for example, the Great Northern had been lavish in the development of hotels—with an eye toward generating more passenger traffic over its railroad line. Similarly, the Northern Pacific had kept the financial props under its subsidiary, the Yellowstone Park Hotel Company, mindful of the indirect profits that Yellowstone National Park brought to the railroad. Mount Rainier had its own modest railroad patron in the Tacoma and Eastern, a subsidiary of the Milwaukee Road, but Mather judged the situation correctly when he decided that Mount Rainier's proximity to Seattle and Tacoma made it more practical to reach for the deep pockets in the local business community rather than try to interest one of the transcontinental railroads in building a hotel at Paradise.

That Mather understood the Rainier National Park Company's interest in Mount Rainier is clear from his early annual reports, in which he promoted national parks as agents of economic growth in the West. In his annual report for 1925, Mather waxed poetic on the topic. The passage is worth quoting because it demonstrates how well the NPS director was able to see through the eyes of all his collaborators in the private sector, including the gentlemen in the Rainier National Park Company. "Every visitor is a potential settler and investor," Mather began.

The march of the huge wagon trains along the scarcely discernible trails in the fifties marked the beginning of the settlement of the West. The new people were the settlers and the builders. They carried with them plows, and the seeds from which the granaries of the future were to be filled. Their descendants are the living pioneers of western development. The new West, however, is being built up by later visitors who came to see, and, having seen, brought their families to become citizens of now large prospering communities. Hundreds of thousands in the past few years have pulled stakes in the East and invested in western ranches and fruit farms, in mines, and other industrial enterprises. In all this the national parks, as the scenic lodestones, through their attractions draw these future settlers and investors for their first trip and in this way contribute their vital share in the prosperity of the institutions, scenic resorts, and general business of the country. [4]

Mather's new concession policy was one of his most important reforms of national park administration. He found a chaotic situation in 1915—not only in Mount Rainier but in all the national parks. Competition between the various tourist concessions within each park was debilitating to them all. The concessioners spent so much effort warding off competitors that they could not give good service to the public. There were too many fly-by-night operators. The messy scene at Longmire Springs, with its ragged line of stables, tent-stores, and advertising signs in addition to the two hotels, was typical. The solution, he argued, was to consolidate tourist services in each park under one licensed operator. Each park concession would be a regulated monopoly: regulated so that the NPS could ensure that it was providing good service, a monopoly so that the operator could be induced to accept low yearly returns on long-term investments. Mather called the concessions "public utilities," a disarming term that suggested their similarity to that other kind of regulated monopoly, the municipal utility company. [5]

The label was somewhat disingenuous. Unlike municipally-controlled utility companies, the RNPC would be under no profit-sharing plan with its own rate-payers, the tourists. Nor would it appeal to tourists for a new bond issue each time it sought to build a new hotel. The company was less accountable to the "public interest," much less the "national interest," than the "public utility" tag would indicate. Of the RNPC's 142 stockholders in 1919, all but nine lived in Seattle or Tacoma, and all but eight were owners, executives, or general managers of businesses in the region. [6] Since park users had no representation whatsoever in the company's decision-making, it was the NPS's task to interpret their interests for them and attempt to influence the company's management accordingly.

The Rainier National Park Company was incorporated on March 1, 1916. It started with a capital stock of $200,000. At the first meeting of the board, Chester Thorne of Tacoma was elected president, and Martin was hired as its general manager with a salary of $5,000 per year (nearly double the salary of the park superintendent.) [7] The RNPC then contracted with the Department of the Interior for the exclusive privilege of providing hotels, inns, camps, and transportation in the park for a period of twenty years beginning on April 24, 1916. [8] Its initial plan of action, outlined that spring, was to build an inn at Paradise, accommodate visitors in two camps at Nisqually Glacier and Paradise Valley, purchase the National Park Inn at Longmire Springs, buy out the various small concessioners, and take over the guide and transportation services.

The Paradise Inn

The new hotel was the centerpiece of the RNPC's development scheme. That summer, before the snow had left the Paradise Valley, construction of Paradise Inn began with the installation of a 250-horsepower, hydroelectric power plant on Van Trump Creek at Christine Falls, two miles below the main development site. This was followed by the establishment of a 100-tent camp for the building crew in Paradise Valley. The RNPC's building contractor, E.C. Cornell, was finally able to break ground for the inn on July 20. Despite a late snowpack and short construction season, Cornell's crew nearly completed Paradise Inn during the summer of 1916. The initial cost of Paradise Inn, not including furnishings and equipment, came to $91,000. [9]

The Paradise Inn was designed by Tacoma architect Frederick Heath. The building comprised three main wings, each one featuring steep, gable roofs and a row of dormer windows in the upper story. In the popular style of the period, the building's large timber frame remained exposed on the interior. A guest standing in the cavernous assembly room on the ground floor could look straight up to the ridge pole three stories overhead. Park Supervisor Dewitt L. Reaburn gave permission to cut dead Alaska cedars from the "silver forest" for the interior decor of the building. This timber, located on the road between Longmire Springs and Paradise, had been fire-killed several years before the establishment of the park and had seasoned to a ghostly light-grey or silver hue. The use of this timber was in keeping with the service policy of using native building materials whenever possible. The great, silver logs were the inn's most appealing feature. [10]

The Paradise Inn opened for business in 1917 with only thirty-seven available guest rooms and a dining room capacity for four hundred guests. The plan was to build more guest rooms as demand increased and the company grew. This turned out to be a sound approach, because during the first two seasons of operation the nation was engaged in World War I and travel to the national parks was somewhat depressed. The federal government placed restrictions on railroad passenger traffic, which reduced the number of visitors to the national parks. So the company's stockholders bided their time through 1917-18. The highlight of the 1918 season at Paradise Inn was the visit of General Hazard Stevens, now in his seventy-sixth year. The white-bearded old pioneer gave an evening program on the occasion of the forty-eighth anniversary of his first recorded ascent of the mountain with Philemon Van Trump in 1870. As it turned out, Stevens' emotional return to Mount Rainier occurred just two months before the end of his life. [11]

|

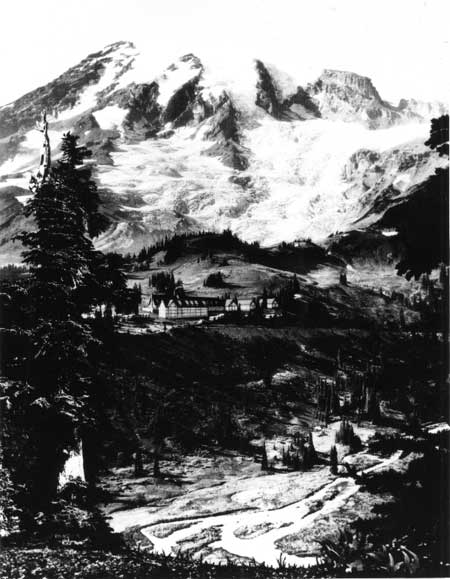

| Paradise Valley and Paradise Park "where the flowers and the glaciers meet." (Asahel Curtis photo courtesy of University of Washington, Negative No. UW4838) |

At the end of 1919, following the Paradise Inn's first peacetime tourist season, the RNPC's stockholders finally had reason to rejoice. The inn had been filled to capacity through most of the season, the RNPC's gross revenues had doubled over the year before, and the company showed a net profit on the year of more than $20,000. The mood of the board of directors' meeting in January 1920 was ebullient. [12] The directors decided to build their first addition to Paradise Inn, a 104-room wing which they called the annex. This time the company employed its own labor and used its own trucks to deliver all building materials to the site. This first stage of expansion of the inn was completed by the end of 1920. [13]

As part of its expansion of the Paradise Inn, the RNPC also requested permission from the NPS to replace its small power plant on Van Trump Creek with a larger installation at the confluence of the Paradise and Nisqually rivers. Before giving final approval to the project, Mather directed Superintendent Toll to consult the NPS's chief landscape engineer, Charles P. Punchard, Jr., on the precise location and character of the project. Mather wanted assurance that the power plant would not be at a point where it would cause a "blemish on the landscape." [14] This accomplished, Mather approved the plan for the new plant, with its dam, penstocks, and powerhouse, which the RNPC completed that fall at a cost of $75,000. The powerlines went from the hydroelectric site past Oh My Point up to the Paradise Inn. [15]

The completion of the annex and power plant ended the first phase of the RNPC's development of the Paradise area. From a commercial point of view, burgeoning visitor demand in the early 1920s almost immediately justified the RNPC's investment. Each year, the Paradise Inn did a thriving business throughout the short season, accounting for more than half of the RNPC's total revenue. The Paradise Inn deserved no less praise as an architectural achievement. Considering the heavy snowfall and short tourist season at Paradise and the condition of the road in 1916, it was rather a bold enterprise to build such a grand hotel so high on Mount Rainier. An ink engraving of the impressive structure soon graced the RNPC's letterhead, bearing the proud caption, "Paradise Inn in Paradise Valley—elevation 5557 ft. Where the flowers and the glaciers meet." The building certainly possessed more grandeur than the two existing hotels at Longmire Springs. It was not in the same class with the log palaces found in certain other national parks—for example, the Old Faithful Inn (completed in 1903), the Glacier Park Lodge (1913), or the Many Glacier Hotel (1915)—but there is no evidence to suggest that Mount Rainier visitors wanted it to be. The Paradise Inn aptly reflected the RNPC's middling position between the undercapitalized park concessions of the pre-1916 era and the railroad-subsidized park concessions of Yellowstone, Glacier, Yosemite, and Grand Canyon.

Developments at Longmire

The RNPC's second priority was to acquire the various enterprises at Longmire and tidy up the place. The National Park Hotel and Transportation Company proved willing to sell out to the RNPC before its five-year contract with the government expired, and the many small concessions with one-year contracts were fairly cooperative as well. The Longmire family interests posed a trickier problem, because the federal government had no leverage for making them sell to the RNPC. But even this situation resolved itself satisfactorily for the time being as the RNPC purchased a twenty-year lease of the property. The transition to a single park concession was accomplished in just over two years.

Some people accused the RNPC of strong-arm tactics in acquiring these interests. After the RNPC purchased John L. Reese's camp equipment and improvements for $8,250 in 1916, past patrons of the camp complained that Reese had been "squeezed out." The RNPC tried to purchase George B. Hall's horse barn and livery service at Longmire Springs and tent camp at Indian Henry's Hunting Ground and got nowhere in 1916. But when Hall died in April 1917, the RNPC negotiated a deal with the attorney for the Hall estate, acquiring the Hall property for $3003. [16] The RNPC then closed the Indian Henry's camp. Superintendent Reaburn, noting that the Indian Henry's trail had always been the most popular pony trip out of Longmire Springs, speculated that the RNPC had closed the camp in order "to cripple the business at Longmire Springs, and force the Longmire Springs Hotel Company to sell their property to the Rainier National Park Company." [17]

In the late spring of 1916, Superintendent Reaburn initiated negotiations between the National Park Hotel and Transportation Company and the RNPC on the sale of the former company's buildings, furnishings, and small fleet of touring cars. The National Park Hotel and Transportation Company's president, James Hughes, wanted $42,500. [18] The negotiations stalled, and the National Park Inn continued under the old management for the 1916 and 1917 seasons. In April 1918, Hughes reopened the negotiations with an offer to sell for $37,000. He accepted the RNPC's counter-offer of $30,000 a few weeks later. [19]

The RNPC got lucky with the Longmire property, which might have continued under separate management indefinitely. In 1916, the Longmire family leased the hotel operation to J.B. Ternes and E.C. Cornell, who built an annex next to the original Longmire Springs Hotel. [20] In 1919, following lengthy, three-way negotiations between the RNPC, the lease holders, and the property owners, the RNPC purchased the buildings together with a twenty year lease on the patented land for $12,000. [21] Ternes became a major shareholder and secretary of the RNPC. The following year, the RNPC moved the new annex across the road to a position adjacent to the National Park Inn, calling it the National Park Inn Annex, and demolished the old Longmire Springs Hotel. Together with the removal of the various tent-stores and outbuildings, this improved the appearance of the Longmire area. [22]

In its first year of operation in the Longmire area, the RNPC opened the National Park Inn for business before the end of April, nearly two months earlier than its customary opening date of June 15. This proved to be a costly mistake; the hotel and restaurant crew were practically alone in the building for six weeks. Even when the tourist season finally got under way, most overnight visitors were intent on driving to the end of the road and staying at the new Paradise Inn or campground. As a result, the inn finished the summer $3,000 in the red. [23]

As the 1920s unfolded, the situation at Longmire left both the RNPC and the park administration dissatisfied. It was clear to the RNPC that the National Park Inn would not be very profitable. The NPS, meanwhile, found that the appearances of the place left much to be desired. [24] Ironically, the RNPC had no sooner cleaned up the Longmire area than it became no more than a pit stop on the road to Paradise, or at best, an overflow area when the Paradise Inn and campground were filled to capacity. Park visitors overwhelmingly preferred to drive to the end of the road and stay in the new Paradise Inn or in the campground there. The RNPC was not inclined to invest very much in the Longmire area to try to change this pattern. So the underlying problem in Longmire was low occupancy in the National Park Inn. After 1920, the company's sole effort to hold park visitors in the Longmire area was to offer special weekly rates at the National Park Inn in order to attract a different clientele. For the most part, the RNPC wanted to invest where the demand was greatest—at Paradise. [25]

The Park Service took a different view of the matter. It was concerned about low occupancy at the National Park Inn because there was so much congestion at Paradise—crowded campgrounds, a shortage of parking spaces, traffic jams, park visitors turned away at the inn. There remained one possibility for rehabilitating Longmire as a tourist destination: the attraction of the mineral springs. Superintendent W.H. Peters recommended that the mineral baths be developed for their medicinal properties, that a natatorium be built, that tennis courts and other outdoor sports facilities be developed. In short, Longmire should be made into a health spa. [26]

In September 1920, the NPS took water samples from eight springs in Mount Rainier National Park, two of them in the Longmire area, and sent them to the Bureau of Chemistry's Hygienic Lab in Washington, D.C. This began more than a year of correspondence between top NPS officials in Washington, experts in the Public Health Service, and the superintendents of Mount Rainier National Park and Hot Springs Reservation, Arkansas. NPS officials concluded that the mineral springs contained no real medicinal value other than the natural benefits that were incidental to a restful and relaxing sojourn in a mountain resort. Nevertheless, it still favored redevelopment of the springs by the RNPC, provided that no false claims were made about the therapeutic powers of the mineral baths. [27]

The RNPC declined to rehabilitate the Longmire Springs mineral baths. In the long run, this was probably fortunate; the park administration would later find the development of mineral baths at Ohanapecosh to be both unsightly and unsanitary, and would have a difficult time closing the establishment down. But it also portended the difficulties that would arise when the RNPC and the NPS did not see eye to eye on how the park should be developed. The park administration's desire to make Longmire into a health resort was motivated in part by its desire to relieve pressure on the Paradise area. This would be a constant theme in park planning from this point forward. And the Park Service's efforts to move visitor services to lower elevations would meet with constant resistance from the RNPC.

Guide Service

The RNPC took over the guide service without any difficulty. Mountain guides who had formerly held individual permits under the Secretary of the Interior simply went to work for the RNPC. In 1917, the RNPC hired Asahel Curtis as its first chief guide. He was followed by Otis B. Sperlin in 1918, Joseph T. Hazard from 1919 to 1920, Frank A. Jacobs from 1921 to 1924, and Harry B. Cunningham from 1925 to 1932. The guide department employed several guides each season, including two Swiss brothers, Hans and Heinie Fuhrer, and a few women such as Alma D. Wagen, a Tacoma high school teacher who was later described as "unique at the time, dressed colorfully, and.. .most competent on the glacier tours of that day." [28]

Summit climbs increased in popularity as word of the guide service's professionalism spread. Approximately 300 people reached the summit of Mount Rainier in 1919, 400 in 1920, and 500 in 1921. [29] In addition to summit trips, the guide service offered regular trips onto the Nisqually and Paradise glaciers, one rock-climbing trip in the Tatoosh Range, and horseback trips such as the "Skyline Trail" around the rim of Paradise Valley. Most of the guides were teachers or college students, and they tried to inform their clients about the natural history of the park as well as lead them safely over the mountain terrain. In this respect, the RNPC's guide service prefigured the nature guide service which the Park Service began to provide in 1922. [30]

The RNPC housed the employees of the guide service in a steep-roofed dormitory building called the Guide House, built in 1919-20. This building, located near the Paradise Inn, also served as an auditorium for slide shows and evening lectures, a cache for search and rescue equipment, and a gathering place for all guided trips out of Paradise. In the early years, it was a hub of activity second only to the inn itself. [31]

Transportation Service

Mather believed that the control of all transportation service by a single park concession was as important as the control of all lodging facilities by one company. Preferably, the two services would be combined in one company. Accordingly, the RNPC set up a transportation department within the company. Three persons who had previously operated passenger automobile service to the park, Frank M. Jacobs, C.E. Atherton, and Frank Hickey, each sold their equipment to the RNPC for company stock. [32]

|

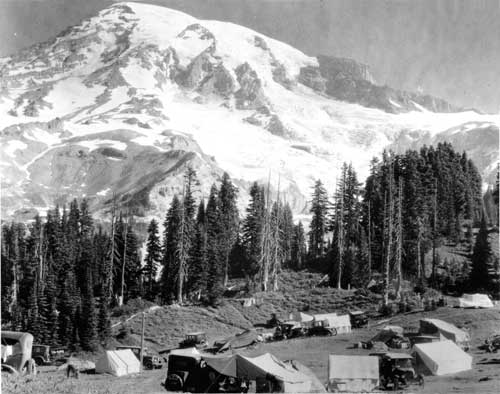

| Paradise Inn and company stages. The concessioner 's transportation department did a thriving business in the 1920s. (O.A. Tomlinson Collection photo courtesy of University of Washington, Negative No. UW1576) |

The RNPC's transportation monopoly was abetted by the state of Washington. A state law required all new stage lines which proposed to operate over the state highways to obtain a permit from the Board of Public Utilities. The law's purpose was to prevent ruinous competition between different transportation venders. In the summer of 1921, the state highway director ruled that the RNPC would be the only carrier between Seattle or Tacoma and points inside Mount Rainier National Park. [33]

The RNPC's transportation monopoly irritated park users more than the RNPC's monopoly on lodging and other services in the park. The company jealously guarded this exclusive privilege, for it was perhaps the most reliable revenue producer among the RNPC's various departments and services. It also raised some of the most complicated legal questions, as will be seen in the next section.

CHALLENGES TO THE NEW CONCESSION POLICY

Nothing in the National Park Service Act spoke directly to the need for a new concession policy in the national parks; this was wholly Mather's initiative. The importance of this policy reform comes into clearer focus when the alternatives are considered: opening up the parks to free competition on the one hand, or eliminating the role of private capital altogether on the other. Mather and his assistants were anxious to see the single concession in Mount Rainier National Park do a good job in serving the public because it was an important test of Mather's new policy. The RNPC was not a large corporation but it had a high profile. Likewise, The Mountaineers and another Seattle-based group called the Cooperative Campers of the Pacific Northwest were local clubs but their challenges to the NPS had more than local significance. When The Mountaineers aimed a broadside at the Park Service's concession policy in a pamphlet published in 1922, it pointedly titled its tract "The Administration of the National Parks." Mather gave these challenges to his policy due consideration.

Cooperative Campers of the Pacific Northwest

The most significant challenge to the new concession policy came from a non-profit, left-leaning, outdoor club known as the Cooperative Campers of the Pacific Northwest. At first, Park Service officials thought the Cooperative Campers could be treated like The Mountaineers or the Boy Scouts—as a non-commercial organization that fell outside of its concession policy. But when the Cooperative Campers began providing transportation from Seattle to its camps in the park, NPS officials decided that the group was taking business away from the RNPC and undermining the concession policy. For its part' the Cooperative Campers insisted that the group offered people of low income an affordable alternative to the concession. The contest involved basic issues of public access versus federal control in the development of Mount Rainier National Park.

The Cooperative Campers was founded in 1916. The group's purpose, as stated in its by-laws, was "to encourage the love of simple living in the open air, and to make the wonders of our Mountains accessible, especially through establishing self-supporting but non-profit making camps for summer vacations." [34] The group required a nominal membership fee of one dollar and invited anyone to join who could satisfy one of the club's officers that he or she could make a "good camper." The group was affiliated with The Mountaineers and the Mazamas, but it differed from those clubs in the fact that it organized summer camps rather than outings. These camps were initially limited to locations inside Mount Rainier National Park. The camps ran for nearly two months and members could join the camp for three days or a week or two weeks. They could stay in one camp or hike from camp to camp around the mountain. Members received summer schedules which listed dates and fees for a wide variety of trips. Group sizes were limited to twenty-five people. [35]

The Cooperative Campers operated on a shoestring budget of a few thousand dollars. The camp cooks, a packer, and an office secretary in Seattle were the only salaried employees of the organization. Camp managers and leaders of hikes did not receive salaries but could receive fee-waivers for their trips. The club's president, elected for a one-year term, served without salary. In its early years, the Cooperative Campers benefited from the energetic leadership of its first president, Anna Louise Strong, a civic activist, writer, and socialist. After Strong's departure in 1919 (she left for the Soviet Union to report on the Russian Revolution), no dominant personality took her place. Major E.S. Ingraham, a pioneer climber of Mount Rainier and longtime leader in the Boy Scouts, remained active in the Cooperative Campers, but did not serve as president.

The Cooperative Campers aimed to strike a middle ground between the camps of the mountain clubs whose members owned their own equipment, and the campgrounds run by the RNPC for automobile tourists. [36] It offered its members help with supplies and equipment. Each camp consisted of four six-man tents, divided into men's and women's quarters, separated by the cook tent. In addition to tents, food, and eating utensils, the camps were stocked with straw mattresses, blankets, alpenstocks, grease paint (sun screen), and other specialty equipment. Camp fees in 1917 were $1.25 per day for shelter, equipment, and meals. Transfer of baggage from camp to camp cost $.50 to $1.00 depending on the distance between camps. Clearly, the cooperative camps offered affordable recreation to people of low income. [37]

In 1917, the Cooperative Campers maintained camps at Paradise, Ohanapecosh Park, Summerland, Glacier Basin, Mystic Lake, and Seattle Park. It was possible to hike from camp to camp more than half way around the mountain. Heady with the group's success, Anna Louise Strong urged readers that summer to sign up and be charter members in what was destined to be the first of many cooperatives to open up "the far recesses of other mountain ranges and other national parks." [38] Did the cooperative camps really have that kind of potential? Probably not. Quite apart from the obstacles that the NPS soon put in the organization's way, the cooperative camps would eventually lose their attraction as members either acquired their own equipment and automobiles and used the public campgrounds built by the NPS, or patronized the hotel and transportation service of the RNPC. But the NPS nevertheless treated the cooperative camps as an unwelcome development, because the camps seemed to undermine the Park Service's concession policy.

The Cooperative Campers' socialist leanings did not escape Mather's notice when he first pondered the issue in December 1917. In addition to her efforts on behalf of the cooperative camps, Anna Louise Strong worked on the staff of the socialist newspaper, the Seattle Union Record, and was an elected member of the Seattle School Board. That year, she had angered Seattle voters by her strident anti-war position in the newspaper, and was now embroiled in recall proceedings. This was irrelevant as far as the cooperative camps were concerned, but Mather judged that in the present context of war-bred, anti-socialist hysteria in the country, the Cooperative Campers might soon self-destruct. When Reaburn asked whether he should prohibit Strong from conducting cooperative camps in the park during the coming summer, Mather suggested that the matter could await the outcome of the recall proceedings. [39]

Ejected from the Seattle School Board that spring, Strong continued to pour her energy into the Cooperative Campers. In the summer of 1918, the group scaled back its operation and maintained just two camps at Paradise and Summerland. She explained to Reaburn, "The war changes many things and many of our men are gone." [40] The camps served 155 and 67 people respectively, but the average stay of campers at Summerland was more than twice as long, at ten days, so the two camps were comparatively busy. It was the Paradise camp that troubled Mather the most, since the camp was in direct competition with the RNPC's campground. Fortunately, Strong indicated to Reaburn at the end of the season that the Cooperative Campers intended to discontinue the Paradise camp next season. These campers had expressed a certain amount of dissatisfaction "due to the inevitable comparison with the standards they see about them and also to the fact that people who ride up in autos expect a different type of camp-life from those who walk." [41] Henceforth, the cooperative camps would not compete with car camping but would concentrate on opening up the backcountry.

This new direction might have alleviated the conflict between the Cooperative Campers and the NPS, except that Strong now asked for permission to take over the old Wigwam Hotel camp at Indian Henry's, which the RNPC had recently purchased and abandoned. According to Strong, the plan met with the RNPC's approval. Mather and Albright both opposed the plan, however. Mather did not want to place the development of the national park's backcountry in the hands of some local organization of campers; Albright was concerned about the quality of service that the cooperative camps would give to the public. [42]

With Strong's request that the park give her the keys to the ranger cabin at Indian Henry's so that the Cooperative Campers could make use of it that winter, Reaburn's patience snapped. In September 1918, he directed one of his rangers to arrest the Cooperative Campers' packer, George Crockett, for receiving pay for his services in the park without having a permit. U.S. Commissioner Edward S. Hall convicted Crockett on the misdemeanor charge and imposed a small fine. Explaining this action to Albright, Reaburn contended that the Cooperative Campers was neither an authorized concession nor an organized outdoor club like the Mazamas or The Mountaineers. The Cooperative Campers did not meet the criteria for the latter because it solicited members through printed circulars and newspaper advertisements. Reaburn also reminded Albright that Strong had been recalled from the School Board for her anti-war statements, and that "her bosom companion, Miss Olivereau was given a penitentiary sentence of 10 years." What really galled the superintendent was Strong's claim that the Cooperative Campers were opening up the backcountry in the park. "As a matter of fact she is spending absolutely nothing in the way of developing, but expects the Service to do a lot of things in the way of fixing up and improving conditions for her camp, having no doubt gotten the impression that we should improve her camp as we have done the public camping grounds." [43] Reaburn thought it was time the NPS held the Cooperative Campers to account, for the organization was practically billing itself as a populist alternative to the RNPC.

At this point, the Cooperative Campers virtually disappears from the historical record until 1921. From later statements it is evident that the Cooperative Campers maintained at least one camp in the park each season at Summerland, and probably the NPS chose to tolerate the group as long as it limited its activities to the east side of the park (away from the RNPC's hotels and camps). Moreover, the personal antagonism between Strong and Reaburn ended in the spring of 1919 with Strong's departure for the Soviet Union and Reaburn's request for an indefinite leave from the NPS. Still another factor which may have worked to deter the NPS from taking a stand against the Cooperative Campers in 1919 or 1920 was the concern about the public backlash it could create against the Park Service. These were the years of the Seattle general strike and the election in Seattle of a socialist mayor. There was a movement afoot for establishing municipally-run automobile camps not only on the outskirts of cities but in nearby mountain areas, too. In September 1920, Mayor Hugh M. Caldwell of Seattle petitioned the Secretary of the Interior for permission to maintain a camp in an unfrequented section of Mount Rainier National Park (where it would not compete with the RNPC facilities). Minimal camp fees would be set to cover the cost of operation. Secretary of the Interior John Barton Payne politely refused this request by suggesting that the city of Seattle could establish a municipal camp in the adjacent national forest instead, but subsequently suggested that a camp could be maintained in the northeast section of the park on a cooperative basis. [44] In this context, the NPS may have deliberately muted its earlier opposition to the Cooperative Campers and bided its time.

In 1921, the RNPC opened a new campground facility at the end of the White River Road. T.H. Martin notified the Cooperative Campers in June that the RNPC had an exclusive automobile concession in the park, and that it objected to the plans of the Cooperative Campers to provide its members with transportation between Seattle and the end of the White River Road. The RNPC planned to offer this service for a fare of between $10 and $12, while the Cooperative Campers intended to charge members $5 to $7. Advised of the situation by Superintendent W.H. Peters, Assistant Director Arno B. Cammerer informed the Cooperative Campers' executive secretary, Norman Huber, that the NPS would not allow the Cooperative Campers to employ its own vehicle in the park. "In order to get the greatest number of people to visit certain sections of the parks that have been opened up," Cammerer explained, "it is necessary for us to install regular service, and in order to make this regular service pay for the benefit of the greatest number we have to insist that no other operators be permitted in competition." Whomever the Cooperative Campers paid to transport campers to the park would be undercutting the RNPC's rates. [45]

But Mather, Albright, and Cammerer found that the Cooperative Campers were not so easily turned aside. The Cooperative Campers purchased their own truck. With the summer season already commenced, Superintendent Peters told his superiors that he saw no alternative but to admit the Cooperative Campers' truck into the park as a private vehicle. After the present summer season, he urged, the NPS would have time to devise a new policy toward the cooperative camps. [46]

That fall, Albright and Cammerer visited Mount Rainier National Park and discussed the Cooperative Campers at length with the superintendent. There was no question that the Cooperative Campers was competing with the RNPC: the cooperative camp at Summerland had received about three times the use that the White River Camp had. [47] The new plan would be to challenge the group's liberal membership policy, treat the group more like an actual camping club than an unauthorized concession, thereby either forcing it into an acceptable mold or running it out of the park. In the coming summer, the Park Service would require the Cooperative Campers to submit a list of members to the superintendent by June 1. No one would be permitted to use the camp whose name was not on the list, and no more than one hundred people would be permitted overall. [48]

The following spring, Superintendent Peters once again advised his superiors to hedge a bit as the summer season drew near. How could the NPS make the 100-person limitation stick if it were challenged? The NPS would be on more legally defensible ground, he argued, if it went back to its earlier position that the Cooperative Campers was an unauthorized concession, and simply disallowed the camp altogether. "It is my belief that the Cooperative Campers are operating in direct and hurtful competition to the concessionaire and that when such an organization is allowed at all we are immediately involved in a maze of fine points impossible of solution," he wrote. [49] Peters wanted to restrict the use of the camp to pre listed members but not to cap it off at one hundred, and then advise the Cooperative Campers at the end of the summer that the camp would not be permitted anymore.

Even with this compromise, however, NPS officials were dragged into a testy correspondence with the Cooperative Campers' new executive secretary, H.W. McKenzie, over the use of the truck in the park. The situation was complicated by the fact that Peters resigned his post in June, only days before the cooperative camp was to open. The newly appointed superintendent, C.L. Nelson, immediately received explicit instructions from Cammerer to stop the Cooperative Campers' truck at the park entrance, check the campers' names against the membership list, and have the RNPC's vehicles ready, if necessary, to provide the group transportation into the park. At the last moment, Nelson countermanded Cammerer s instructions and directed the White River district ranger to allow the Cooperative Campers' truck to enter the park, and to admit unlisted members along with members who were on the list which the NPS had obtained on June 10. In defense of this act of insubordination, Nelson told his superiors that local public sentiment about the Cooperative Campers was divided, and that he did not want to give the organization an issue with which to arouse popular feeling against the Park Service and the RNPC. [50]

Cammerer sharply reprimanded the new superintendent, stating that his indecisiveness would cost the NPS support when it held a public hearing on this troublesome issue in Seattle in the fall. Cammerer insisted that for the remainder of the season the park staff was to refuse official permission for use of the camp to all unlisted members, and it would keep a record of all violators. This would be used to discredit the Cooperative Campers in the public hearing. [51]

Ironically, the Cooperative Campers appears not to have survived to attend that hearing, which was finally held on February 19-20, 1923 at the Seattle Chamber of Commerce building. If the Cooperative Campers still existed in 1923, it must have moved its operation somewhere outside Mount Rainier National Park. It seems more likely that the group disbanded. The proliferation of free public campgrounds in the national parks and forests, along with municipal camps and public and private organization camps, made the cooperative camps obsolete. When the Playground and Recreation Association of America published a 634-page manual on organized camping in 1924, it did not even mention cooperative camps. [52] It remains unclear whether the low income people who patronized the cooperative camps found other means of affordable camping as the nation's camping culture evolved, or were forced to turn to other kinds of recreation within the city. [53]

The Mountaineers

In November 1922, The Mountaineers joined the attack on the Park Service's concession policy. With its 1,000-strong membership and long record of solid support for national parks, this must have been a disappointment to NPS officials. Following an investigation of "the administration of national parks," the club resolved:

1. That the administration of national parks be liberalized with the view to making their enjoyment by the public less burdensome in its restrictions.

2. That cooperative camps or camps of organizations desiring to furnish service to their members at cost be permitted under proper regulations.

3. That further attention be paid to the comfort of campers who are not large patrons of the established concessionaires.

4. That the financial profits resulting from the operations of the various concessionaires be made available to public scrutiny, to the end that in the establishment of rates the voice of the public may be expressed equally with that of the concessionaires.

5. That the rules relating to automobiles be subjected to fundamental revision. [54]

The investigating committee's report accused the NPS of kowtowing to the park concessions in general and to the RNPC in particular. The committee alleged that the profit-driven park concessions were gaining too much influence, treating the park superintendents as their own agents in dealing with NPS officialdom. "The resulting tendency is for the development of the parks to proceed disproportionately along lines of commercial profit," the committee reported. "The administration of national parks, although based upon high ideals of public service, has not escaped this evil." [55]

The Mountaineers' investigating committee characterized the Cooperative Campers as a "benevolent" organization which had made camping trips possible "to a limited number of persons of congenial tastes and modest means, many of whom would not be able to patronize the regular concessionaire." The committee stopped just short of endorsing the cooperative camps, but it insisted that any effort by the NPS to eliminate the camps should be done in a lawful way. It was evident to the committee that the park administration was determined to force the Cooperative Campers out of the park, and it found the record of actions taken against this group to be "arbitrary," "insincere," and "petty." [56]

The committee reserved its most stinging criticism for the NPS prohibition against hired auto stages. The NPS and the RNPC maintained that the park concession had the exclusive privilege of providing transportation services between Seattle or Tacoma and points inside the national park. The controversy over the Cooperative Campers' truck led the NPS to interpret the RNPC's transportation monopoly in the broadest possible way. As a result, the NPS inadvertently thwarted The Mountaineers as well. On a Labor Day weekend outing in 1922, a large party of Mountaineers was inconvenienced and humiliated when the park authorities made them transfer their whole party and all their gear from hired auto stages to RNPC cars at the park entrance. [57] In the view of the committee, the NPS had gone way too far in protecting the concession s monopoly, and was fencing the park with so many regulations as to make it difficult for the public to gain access to it.

The RNPC's officers reacted angrily to The Mountaineers' pamphlet and demanded a retraction of some of its statements. Other conservation groups, meanwhile, gave the report mixed reviews. The Mountaineers received letters from the American Civic Association, the National Parks Association, the Mazamas, the Sierra Club, and various other mountain clubs. But The Mountaineers stood by the committee report. [58] In January 1923, The Mountaineers' president, Edmund S. Meany, received a letter from Cammerer stating that the NPS wanted to hold a public meeting in Seattle at which these various complaints could be discussed. [59]

The meeting, held on February 19-20, 1923 in the Seattle Chamber of Commerce assembly rooms, was attended by Albright, Nelson, and former Superintendent Roger W. Toll (then superintendent of Rocky Mountain National Park). The representative for The Mountaineers, Irving M. Clark, told the NPS officials that The Mountaineers did not endorse the Park Service's regulated monopoly policy, but it would not try to oppose it either. Rather, it sought changes in the policy that would allow more flexibility. Specifically, The Mountaineers wanted the admittance of hired cars, the allowance of cooperative camps "in larger parks where there is ample room for everybody," an end to the requirement that all horse riders hire guides, full disclosure of the concessionaire's yearly profits, better sanitation in the public campgrounds, and overall clarification of the park's rules and regulations. [60]

It is difficult to assess the overall effect of The Mountaineers and the Cooperative Campers on park policy in the early 1920s. The documentary evidence in the Park Service's files does not support the conclusion that the agitation by these groups brought about specific reforms of park policy. No single example can be cited of a park rule or policy being changed in order to satisfy their demands. Nevertheless, it may have been partly due to the influence of The Mountaineers and the Cooperative Campers that the NPS moved into two areas of public service in Mount Rainier National Park in the early 1920s which it had formerly left to the RNPC. The first of these was the nature guide service, a forerunner of the NPS interpretive program. This is discussed in a later chapter. The second public service was the development of free public campgrounds, discussed below. In these two new areas of national park administration, Mount Rainier National Park was on the cutting edge. Coming so soon after the successful consolidation of visitor services under a single park concession, these developments would seem to indicate a deliberate scaling back of the Park Service's partnership with the RNPC in response to the challenges to Mather's concession policy by the Cooperative Campers and The Mountaineers.

Free Public Campgrounds

In 1915, most overnight camping in Mount Rainier National Park was conducted in the so-called "hotel camps" at Paradise Park, Longmire Springs, and Indian Henry's Hunting Ground. Campers slept in canvas-walled tents and ate meals prepared by the camp host. Relatively few people had their own camping equipment; those who did were apt to join large, organized outings like those of The Mountaineers. Less than a decade later, more than ninety percent of visitors to Mount Rainier National Park wanted to camp in public automobile campgrounds. [61] Typically they had their own tents, sleeping bags, and cooking gear (much of it acquired from army surplus outlets after World War I). They required no more than drinking water and toilet facilities to complete their outfit, and after paying their entrance fee, they expected to be able to camp in the park for free. Most of them came in small parties by private automobile. This was an extraordinary change in the pattern of visitor use to take place in a single decade. In a sense, Mather's conception of the role that the national park concession would play was outmoded before it was ten years old.

The Park Service inherited a system of privately-owned camps that was barely able to cope with the rising number of campers in the national parks. The hotel camps were overcrowded, overpriced, and often located in places that inhibited the flow of automobile traffic. In all the parks, there was a growing problem of sanitation. On the July 4 weekend in 1916, for example, some five thousand people were camped in a one-square-mile area of the Yosemite Valley, completely overrunning the limited camp facilities there. That year the Department of the Interior commissioned an experienced hotel operator, one J.A. Hill of Chicago, to make a detailed inspection of hotels and camps in the national park system. On the basis of Hill's report, Supervisor of National Parks Robert B. Marshall found that the sanitation problem was the most pressing concern in every park. As a result, the department recommended that Congress appropriate funds for the development of sanitation and water systems in the national parks, taking over an area of park development which had previously been left to private enterprise. [62]

The government's involvement in campground development in Mount Rainier National Park began in 1918, with $8,000 expended in clearing camp sites and installing sewer and water systems. Free public camping areas were developed at Longmire, Paradise, and one mile inside Nisqually Entrance. [63] Yet the system was still only rudimentary and existed alongside a number of new hotel camps developed by the RNPC. The largest hotel camps were at Longmire and Paradise where campers could avail themselves of the dining facilities connected with the hotel. The RNPC established additional camps at Nisqually Entrance and the Nisqually Glacier overlook. (In this era, the road bridge over the Nisqually River afforded a dramatic view of the Nisqually Glacier terminus; the glacier has since receded out of sight.)

Mather's comments on the RNPC's camps in 1918 reveal a strategy of campground development that was in transition. "Paradise and Nisqually Glacier Camps with their lunch pavilions and a-la-carte service fill an important need in this park," Mather reported.

The Paradise Camp is especially popular because here the tourist is at liberty to live under almost any conditions that he may choose. He can live in one of the tents of the camp, using his own bedding and cooking his own meals, or he can rent bedding at a nominal price and eat at the lunch pavilion; or he may bring his own tent equipment and eat at the lunch pavilion or purchase his supplies there and do his own cooking. [64]

The variety of needs which campers presented seemed to call for a mixed system of hotel camps and free public campgrounds (not to mention cooperative camps, which Mather omitted from his report). Mather could not have foreseen how quickly the demand for public campgrounds would grow, nor how quickly the hotel camps would become obsolete.

The sanitation problem in Mount Rainier's public campgrounds continued to draw Mather's attention. In 1920, he recommended that the campgrounds should have better facilities for sewage and garbage disposal, and that these should be installed by the government. "As a general thing," he commented, "all public utilities of this kind should be owned and operated at a profit by the Government, and should include power plants, telephone systems, and water systems, as well as sewer systems." In Mount Rainier National Park it was too late for the government to build the power plant, as this had already been accomplished by the RNPC. But the principle still held, in Mather's view, that the government must take responsibility for basic services that the hotels had provided prior to World War 1. [65]

Over the next two years, the public campgrounds began to assume a more modern shape. The Park Service improved the sewer system at the Paradise and Longmire campgrounds and installed water taps and flush toilets. Park staffers put in camp stoves and tables and established individual camp sites within the cleared area. The Longmire campground was equipped with electric lights. Superintendent Nelson assigned a caretaker to each campground, whose duties were to police the grounds and keep the place clean. In 1922, a sanitary engineer from the U.S. Public Health Service pronounced the campgrounds at Mount Rainier National Park as clean as any he had inspected in the national parks. This was all the more impressive considering that the campground at Paradise was one of the busiest in the national park system. [66]

|

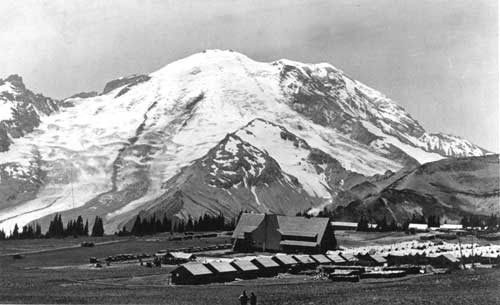

| Paradise public campground in the 1920s. (O.A. Tomlinson Collection photo courtesy of University of Washington, Negative No. UW15699) |

Still the burgeoning demand for camp sites outstripped what the NPS and the RNPC could supply. In 1923, Mather secured $25,000 for a new campground at Longmire on the south side of the Nisqually River. Most of the funds were earmarked for a bridge and loop road, while other line items included camp site development, water and sewer systems, a community kitchen, and electric lights. The campground was state-of-the-art, oriented to the automobile camper. [67] A smaller public campground was laid out at White River that year, too, complementing the RNPC's White River Camp which had opened two years before.

Yet these improvements fell short of what the national park required. "Travel has grown to such an extent," Mather commented in his annual report on Mount Rainier for 1923, "that the comparatively small midweek crowds desiring camping space could not be comfortably accommodated this year." [68]

Expansion of the public campgrounds continued in 1925. The Paradise and Longmire campgrounds now could accommodate about 800 people each, the White River campground could accommodate about 500, and a new campground at Ipsut Creek, on the Carbon River road, could accommodate about 400. In addition, unimproved sites were located on the road to Paradise at Kautz Creek and the Nisqually River, and various points along the White River Road. Together, the unimproved camps could accommodate another 700 people. With these developments, it became clear that the government had taken over responsibility for camping facilities in the park. By the mid-1920s, visitors to Mount Rainier had come to expect that the national park would provide free public campgrounds, complete with running water, toilets, chopped firewood, and evening campfire programs. [69]

The RNPC's camps declined in popularity as the free public campgrounds became more attractive. Superintendent Tomlinson noted in 1925, "Bungalow tents maintained as a part of the Paradise Inn operation are not popular with the visiting public. A great majority of the patrons prefer rooms inside the building and are willing to pay the additional charge for that class of accommodation." [70] For Tomlinson, this underscored the need for additional hotel accommodations at Paradise. In other words, he did not expect the RNPC to stay in the hotel camp business. What had been left to private enterprise in 1915, and considered a partnership enterprise in 1918, was henceforward to be exclusively a government enterprise. This represented a significant evolution in the Park Service's concession policy.

Did local dissatisfaction with the single concession policy in Mount Rainier National Park have something to do with this change? Perhaps. Certainly the development of free public campgrounds proceeded apace in Mount Rainier National Park in the early 1920s. But NPS officials may have been reacting on their own initiative to the pressures of the automobile culture and the growing number of weekend visitors from Seattle and Tacoma regardless of any prompting from The Mountaineers or the Cooperative Campers. Whatever the case may have been, the development of free public campgrounds silenced the criticism from these groups.

GROWTH OF THE PARK CONCESSION

When Mather got together with Seattle and Tacoma businessmen in 1915 to form a partnership of public and private investment in the development of Mount Rainier National Park, neither party anticipated the pace at which visitor use would grow. Mount Rainier's total annual visitation shot from 34,814 visitors in 1915, to 123,708 visitors in 1923, on the way to 265,620 visitors in 1930. [71] For a brief period in 1924-25, Mount Rainier passed Yellowstone as the second-most visited national park in the United States (though well below the annual visitation of Rocky Mountain). At the end of this period it remained a close third. [72]

The driving force behind these numbers was, of course, the sensational spread of the automobile in American society. As early as 1923, it was claimed that one in two American families owned their own car. Mather reacted to the spread of the automobile with glee. He supported the automobile as the most democratic means of opening up the parks to the people, and of building up a strong constituency of national park users. His biographer, Robert Shankland, wryly commented that "Mather could recognize manna when he saw it." [73] Significantly, the businessmen who formed the RNPC were less than enthusiastic about the growing dominance of the automobile in the national park. As the company's officers consistently pointed out, the RNPC made its money from patrons who traveled by train. These were the people who boarded the company's auto stages in Tacoma and stayed at the Paradise Inn. Automobile travelers typically came and went without patronizing anything but the RNPC's restrooms. [74]

The RNPC liked to portray itself as the victim of its special position in the national park. Company officers insisted that the NPS required the RNPC to make sacrifices for the public interest again and again, either by providing services that did not make a profit or by foregoing promising developments that would make up the company's losses elsewhere. The company also tended to get the public's ire for things that were beyond its control, in spite of its best public relations efforts. "Don't forget that the Park Company is the 'goat' for much criticism based on National Park regulations and restrictions," the RNPC's general manager once told a local magazine reporter. [75] One of the difficulties of sorting out the RNPC's role in the development of Mount Rainier National Park is that the company's somewhat plaintive public relations stance contained a modicum of truth: the RNPC was in fact forced to make financial sacrifices in the public interest, and it was indeed maligned unfairly by local public opinion.

The RNPC was victimized most of all, however, by the spread of the automobile. While railroads brought tourists to national park hotels, automobiles brought tourists to national park campgrounds. Although Mount Rainier jockeyed for position with Yellowstone as the second-most heavily visited park in the United States, it was a distant fourth after Grand Canyon, Glacier, and Yellowstone in the number of train passengers received. This disparity was a source of constant frustration to the RNPC, which tried everything in its power to get more out-of-state train passengers to come to the park. The inundation of the park with automobilists actually worked to the RNPC's disadvantage, because it made the transcontinental railroads wary of all the RNPC's overtures.

The RNPC's impressive capital investment in Mount Rainier National Park during the 1920s is best understood as an effort to reconcile two objectives. The first objective was to cooperate with the NPS's plan for the development of the park—a development plan, nevertheless, which pandered more and more to the automobilist. The second objective was to interest one or more of the transcontinental railroads in exploiting Mount Rainier in the same way Yellowstone, Glacier, and Grand Canyon were exploited—with a branch line to the park and one or two well-financed grand hotels. With the advantage of hindsight, it would seem that the glory days of the big national park hotels were past in the 1920s. Yet surprisingly, RNPC officials did manage, with help from Mather and Albright, to interest the Northern Pacific, Great Northern, Union Pacific, and Milwaukee Road in a $2.5 million joint development proposal in 1928-29. The RNPC, as shall be seen, came within an ace of realizing its dream just prior to the Great Depression.

Extending the Visitor Season

It was the RNPC's perennial desire that the NPS open the road to Paradise as early in the season as possible. Late-melting snowpacks usually precluded outdoor camping at Paradise until mid-July, but the inn would attract visitors as soon as the road was plowed. Indeed, so anxious was the RNPC to get the visitor season started in June that for several years it operated a saddle horse and baggage sled service from Longmire in order to get tourists up to Paradise Inn prior to the opening of the road. Unfortunately, the company received many complaints from visitors about the discomforts that this trip entailed. [76]

Opening the road to Paradise was a yearly race against time. NPS road crews used a tractor, a steam shovel, army-surplus TNT, and even hand shovels to get the job done. Floyd Schmoe, the RNPC's winter caretaker in 1919-20, gave a vivid picture of this work in his book, A Year in Paradise.

Day by day the sound of the shovel grew closer, and soon from the inn we could see the clanking, stuttering machine slowly creeping up the deep trough it was gnawing through the layers of snow....

The next day was Sunday, July 4; and we celebrated it by cheering the government road crew and the weary steam shovel around the last bend. They arrived in front of the inn about four in the afternoon—and directly behind the government trucks came the big red buses of the Park Company. The first ones were filled with college girl waitresses and maids, college boy guides, bellboys, busboys, tent boys, dishwashers, and sundry others. Then not a hundred yards behind this bus there were two busloads of tourists. [77]

The most dramatic race against time occurred the following year, in 1921. That April, RNPC President David Whitcomb boldly slated a convention of the National Association of Building Owners and Managers for June 26, then negotiated with Albright to share costs with the government for an all-out effort to open the road by that date. On May 10, Mather wired Superintendent Peters that he wanted the road opened in time for the convention, with photographs to document the whole process. On May 23, Mather reiterated this request, adding that the unusually heavy snowfall made the opening of the road "in the nature of an emergency." On June 14, word came from Superintendent Peters that the weight of the snow shovel was damaging the cribbing on the switchbacks above Narada Falls, but that they were pushing ahead with dynamite and hand labor. Finally, on July 9, two weeks after the convention, came the long-awaited telegram from Peters: "Automobile reached Paradise Inn." Then it was time to reckon the costs—$4,000 to $5,000 for the RNPC and approximately double that amount for the NPS. Albright and Cammerer consulted Mather and decided not to ask the company for a contribution to the $4,000 cost overrun. [78]

Similar excitement occurred earlier each season as the first tourist cars reached Longmire. Peters' monthly report for May 1921 described the scene:

To the Chevrolet Motor Company of Seattle goes the credit of being the first to reach Longmire Springs by auto. After two unsuccessful attempts, they drove one of their cars through to the Springs on Sunday, May 8, while there was still about two feet of snow on the ground. A rather ingenious device of extension wooden ladders, was used for getting over the deeper drifts, which proved very effective.

Later in the day The Blangy Motor Company, authorized by Ford dealer of Tacoma, brought a car to Longmire without the use of any mechanical device whatsoever; and to the Ford should go the credit of really breaking the road to Longmire Springs. [79]

It was not long before the Park Service and the RNPC began to discuss Mount Rainier's potential as a winter resort. Prior to 1923, some 1,200 to 1,400 Northwesterners snowshoed or skied into the park each winter, many on weekend outings with The Mountaineers. Beginning in that year, the Park Service kept the road open all year as far as Longmire. The RNPC rented out snowshoes, skis, and toboggans, and kept the National Park Inn open "informally." Ten thousand people took this opportunity to visit the park during the first winter season of 1923-24, most of them coming only for the day.

In the winter of 1924-25, the RNPC tried to attract more people to the park by bringing in a team of thirteen Alaskan sled dogs and an Eskimo driver. [80] Tourists paid a fare to ride through the Douglas fir and hemlock forest on the dog sled. This was continued for several years. No one questioned the fact that the dog sled was completely out of context at Mount Rainier; rather, it was considered another form of winter sport along with the popular toboggan run at Longmire and the ski and snowshoe trips up to Paradise. [81]

From the Park Service's standpoint, the use of the park for winter recreation was a great success. From the RNPC's standpoint, the winter operation was a disappointment because it did not pay for itself. The inn could only afford to open during the weekends, and the employees had to be run in and out of the park each Saturday and Sunday on a company bus. While the company lost money each winter season, it continued to operate through each winter in part as a public service, in part with the hope of building up a larger winter clientele over time. [82]

The First Aerial Tramway Proposal

Mount Rainier's real potential as a winter sports center lay in getting people to Paradise. Longmire experienced frequent rain and above-freezing temperatures during the winter, while Paradise's extra elevation assured it of much better snow conditions. With this in mind, the RNPC's T.H. Martin in 1924 proposed an aerial tramway from the Nisqually road bridge up the mountainside to Paradise. It would be purely functional, an alternative to the road during the three-quarters of the year when the road was closed. Superintendent Tomlinson forwarded this proposal to Mather with the comment that the tramway would make Paradise available for winter use and therefore deserved further study. [83]

The tramway proposal went no further for three and a half years, or until January 1928. Then Martin tried to link the tramway development to the construction of a second hotel, Paradise Lodge, at Paradise. "It is our definite plan to maintain the new hotel on an all year basis," Martin wrote, "and to do this it will, of course, be necessary to have some sort of comfortable and practicable method of transportation to Paradise Valley throughout the winter." [84] RNPC President H.A. Rhodes assured Mather that the tramway would not be promoted as a novelty or "Coney Island type of amusement." [85] The RN PC held that the only alternative to a tramway was for the NPS to keep the road open all winter—at an estimated cost of $100,000 per year. Of course, another alternative was to operate the new hotel on a seasonal basis just like the Paradise Inn, but NPS officials never broached this possibility with the RNPC out of concern that the hotel would not be built. NPS officials did not endorse the RNPC's premise that the expansion of Paradise facilities required that the area have a winter tourist season, but they did not take issue with it either.

The tramway proposal stirred opposition in the Park Service. Chief Landscape Engineer Thomas C. Vint observed that the tramway would mar one of the most spectacular roadside views in the park—the view of the Nisqually Glacier from the Glacier Bridge. Others worried that it would be precedent-setting, opening the door for tramways to be built to the tops of peaks in other national parks. The fact that many such tramways could be found in the Alps was no consolation to them; a review of these European engineering works indicated that they were built without much regard for scenic preservation. Still another concern was that local organizations including The Mountaineers and the Rainier National Park Advisory Board might oppose the project. [86]

Mather gave this issue his close attention, consulting not only his own landscape architects, but also the National Commission of Fine Arts in New York City. In August 1928, he gave the project his tentative approval, explaining his decision to Superintendent Tomlinson thus:

This is not a proposition having in view a spectacular trip, nor to make a scenic point in a park available at greater convenience to the traveling public, such as the proposed tramway to the top of Mount Hood contemplated or the existing cograil to the top of Pikes Peak presents, but an arrangement whereby the future hotel will be made accessible during the winter months for winter sports and travel from the most readily accessible point on the road. It therefore cannot be pointed to as a precedent by any other park operators, and any other such applications would have to be passed on their merits. [87]

The tramway proposal fizzled one year later, in the summer of 1929. The NPS remained tentatively supportive to the end, and the decision not to go forward appears to have rested with the RNPC rather than the NPS and to have been based on economics rather than aesthetics. After completing the new Paradise Lodge in 1928, the RNPC was in a weak financial condition. As discussed below, company officials were trying diligently to work out a plan with the major Pacific Northwest railroads to refinance the company. This circumstance seems to have been the crucial one in causing the tramway proposal to fizzle.

Nevertheless, the Park Service's evolving position in the first half of 1929 is instructive. The two major points of concern—that the tramway would mar the scenery, and that it would set a bad precedent—continued to cause a great deal of ambivalence. Tomlinson worked closely with the RNPC's hired engineer, Richard Ernst from the German firm of Blechiert & Company, to ensure that the visual intrusiveness of the tramway would be minimized. He was disappointed to learn, for example, that the loading station would have to be placed below instead of above the road, so that it would now be in plain view to anyone approaching the Glacier Bridge from Ricksecker Point. [88] As for the claim that it would not be precedent-setting, this did not deter Assistant Director Albright from holding a conference with Ernst and various other tramway experts on both it and the Yosemite Valley-Glacier Point tramway proposal. [89] When the Secretary of Agriculture spoke out against the proposed aerial tramway to the summit of Mount Hood, NPS officials felt compelled to urge the officers of the RNPC to "keep the soft pedal on their project as far as publicity is concerned." [90] It was clear to NPS officials that they could not treat the RNPC proposal as an isolated case.

The other interesting point that the tramway proposal brought to light was the attitude of The Mountaineers. The Tacoma Mountaineers came out squarely in support of the proposal in March 1929. [91] The Seattle Mountaineers waited for a copy of Ernst's report in April before passing judgment; then it too expressed support. On May 9, The Mountaineers's Board of Trustees gave unanimous approval to the project. Superintendent Tomlinson was somewhat taken aback by this. [92] Earlier, the NPS had not wanted to approve the project without The Mountaineers's support; now it sought some indication that The Mountaineers would stand behind it should the NPS decide to oppose the installation.