|

MOUNT RAINIER

Wonderland An Administrative History of Mount Rainier National Park |

|

| PART THREE: YEARS OF PROMISE, 1915-1930 |

VIII. THE PARK UNDER CONSTRUCTION

INTRODUCTION

Mount Rainier National Park was profoundly influenced by the general prosperity of the nation in the period 1916-1929. The people's enthusiasm for the automobile, the generous support of the federal government for road-building, and the national mood of exuberance that propelled so many people to explore the outdoors, all contributed to make this period a time of development for the park. The number of park visitors grew from 30,000 in 1915 to 250,000 in 1929; road construction spread from the southwest corner to the southeast and northwest corners; hotel and campground construction proliferated.

During these years Mount Rainier was a park under construction. Each summer, road construction crews were at work in at least two sections of the park, sometimes on roads that were already opened to the public. Road crew camps were nearly as conspicuous as public campgrounds. During the typical construction season, the sound of blasting could be heard on many days of the week. On the road to Paradise, construction crews worked at night to avoid the crush of daytime traffic.

The construction involved an unprecedented amount of planning and coordination between federal and state agencies and the private sector. It involved not only road development in the park, but the construction of county roads and state highways all around the park, too. By the end of this era, it was estimated that the development projects at the park would cost a total of $31 million. Washington state would spend $15 million on access roads, the federal government would spend $11 million on road and campground construction and administration, and the Rainier National Park Company would invest $5 million in hotels and other facilities. [1] The exact figures were disputable, but contemporaries clearly regarded the development of the park as a combined effort.

Road building in the 1920s permanently divided the park into front country and backcountry. In 1920 most of the park was still roadless; at the end of the decade all of the roads that exist in the park today were either built or surveyed. Road building involved more public debate and consumed more of the park's annual budget than most other aspects of park administration in this era combined.

THE POLITICS OF ROAD DEVELOPMENT

To understand the intensity of the public debate over road building in Mount Rainier, it is necessary to consider briefly the wider context of road building in the United States in this era. The rapid spread of the automobile in the early twentieth century focused public attention on the need for better roads. A public debate developed over how the roads would be built and improved—whether it would be by federal or local initiative, and whether federal aid should be used to develop a system of national highways or should go to the improvement of country roads that were almost impassable by automobile. Heading this debate were the many automobile clubs, whose campaign for greater public investment in roads was known as the good roads movement. A landmark act of Congress in the nation's highway policy was the Federal Aid Road Act of 1916, which made the first large appropriation ($75 million) for the improvement of rural post roads. This was followed by the Federal Highway Act of 1921, which appropriated an initial $75 million for the development of an interstate highway system. These were massive federal spending programs by the standards of the day. Meanwhile, states formed their own highway departments (as required in order to receive matching funds under the Federal Aid Road Act). By the 1920s, federal and state spending on roads was outpacing that of most counties. [2]

As increasing numbers of middle-class families acquired automobiles and took summer vacations to the national parks in the West, the good roads movement formed a natural alliance with the promoters of national parks in the See America First movement. Two associations were emblematic of this alliance: the National Parks Highway Association, based in Spokane, Washington; and the National Park-to-Park Highway Association, based in Cody, Wyoming. Stephen Mather carefully cultivated grass-roots support for the national parks through these and similar organizations. With Mather's help and the support of the American Automobile Association, the National Park-to-Park Highway became an officially-designated interstate route in 1920. Mather hailed the new "highway" as an important milestone in his effort to make the national parks an integral part of the economic life of the nation. The National Park-to-Park Highway, Mather asserted, would not only make the parks more accessible "but would aid in the further development of the West by bringing its remarkable industrial resources vividly to the attention of the traveling public and cause many tourists to settle there." [3] The good roads movement saw road development as a catalyst for economic growth. National park boosters like Mather saw the development of access roads as being of vital importance if the national parks were to succeed at being what he called the "scenic lodestones" of the West.

At the local level, the Mount Rainier National Park boosters and the good roads movement coalesced in the Rainier National Park Advisory Board (originally the Seattle-Tacoma Rainier National Park Committee). The organization's chairman, photographer Asahel Curtis, epitomized the close relationship between scenic preservation and road development. Serving as chairman of the Advisory Board until the mid-1930s, Curtis mediated between the automobile clubs, chambers of commerce, and the state highway commissioner on the one hand and NPS officials, the RNPC, and The Mountaineers on the other. Indeed, at times during his long tenure as chairman of the Rainier National Park Advisory Board, Curtis also served as chairman of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce. It was said that the main purpose of the Rainier National Park Advisory Board was to coordinate the development of state and county access roads with park roads and to bring various western Washington entities together so that the development of Mount Rainier National Park would not be waylaid by petty rivalries at the local level. [4]

The Rainier National Park Advisory Board tried to influence the park's road development at every step in the process, from the conceptualization of a road network, to the allocation of funds and prioritization of surveys and construction contracts, on down to the inclusion of design features such as scenic turnouts. Certainly the NPS had the dominant part in formulating the park's road development plans, but it received an enormous amount of input from Curtis and the Advisory Board. Where the board occasionally proved useful to the NPS was in lobbying members of Congress during the park appropriations process. The board also lobbied state and county officials on behalf of the access roads to Mount Rainier. Despite the board's commercial orientation and Curtis's rather prickly personality, Mather, Albright, Cammerer, and the park superintendents all treated the Advisory Board with respect.

Another factor in the politics of road building was the transfer of administration from agency to agency. It will be recalled that the Army Corps of Engineers turned over road construction to the Department of the Interior in 1911 (see Chapter V). The new NPS inherited this responsibility in 1916, and one year later Mather set up an Engineering Department under former Army engineer George E. Goodwin. From his main office in Portland, Goodwin kept in close touch with road planning at Mount Rainier. But Mather eventually grew dissatisfied with Goodwin, partly in connection with his foot-dragging over the Westside Road in Mount Rainier National Park, so he transferred responsibility for road design and construction over to the Bureau of Public Roads. [5] The transfer of administration was also consistent with Mather's pledge to keep the NPS tightly focused and to draw on the expertise of other government bureaus where needed. Henceforth, the NPS decided generally where the roads would go and the Bureau of Public Roads surveyed and designed the roads. NPS landscape engineers continued to have input on all phases of the work, however.

It was the park superintendent's job, meanwhile, to recommend overall road development plans and to oversee road construction contracts. It was no accident that four of Mather's five superintendent appointees at Mount Rainier were experienced road builders. Superintendent Dewitt L. Reaburn (1915-18) was a former USGS topographic engineer with railroad building experience in Alaska and South America. W.H. Peters (1920-22) was a civil engineer by background and superintendent of Grand Canyon before transferring to Mount Rainier. C.L. Nelson (1922-23) was also formerly an engineer with the USGS. These men had experience in the political landscape associated with road building. Mount Rainier s longest-serving superintendent, Owen A. Tomlinson (1923-41), had built roads and trails during his twenty years of service in the American-occupied Philippines.

The politics of road building involved so many entities and interests that no one factor can be singled out as a predominant influence in shaping Mount Rainier National Park's road network in this era. Rather, Mount Rainier's road network may be seen as a product of several competing influences. These may be summarized as follows:

1. A desire to open up the four corners of the park for use. While not everyone agreed on the desirability of a high road encircling the mountain, everyone did agree that there should be road access to each corner of the park. At this minimum level of development, established usage by local interests practically dictated the location of roads. In the northwest corner of the park, the Carbon River was the obvious and well-established route used by tourists since the 1880s. In the northeast corner, the existing wagon road up the White River to Glacier Basin laid the groundwork for subsequent road development. In the southeast corner, local people had already cut a trail up the Ohanapecosh River to the Ohanapecosh Hot Springs. In each instance, the question was not whether these routes would be improved for automobile access, but when.

2. A desire to retain sections of the park in a primitive condition. As early as 1924, Mather stated that it was not the Park Service's intention to "gridiron" the national parks with roads. [6] Eventually the idea would form that Mount Rainier's north side should be spared any road development. The idea of retaining a large primitive area within the national park served as a brake on Mount Rainier road development.

3. A desire to relieve congestion. Opening up other corners of the park would relieve pressure on Paradise in the short term, but ultimately the park required connecting roads between these points. "Stub-end roads," as Superintendent Tomlinson referred to them, created more congestion than through-roads. [7] Park administrators saw roads not only as a way of giving the public access to scenic points, but for keeping the public circulating through the park. These would be scenic roads, allowing many visitors to experience the national park through their car windows or from scenic turnouts.

4. A need to cooperate with state and county road planning. The state and county roads leading to Mount Rainier National Park had a profound effect on the evolution of the park's road net. NPS officials had limited ability to influence where these access roads went. It was necessary to adjust park planning to developments outside the park. While the construction of a state highway over Chinook Pass (State Route 410) tended to intensify development of the east side of the park, the languishing effort by Pierce County to build a road from Fairfax toward the northwest corner of the park had the exact opposite effect on the park's westside development.

5. A need to expend park road appropriations efficiently. The short construction season in Mount Rainier, as in most national parks, necessitated careful planning in letting contracts for road building. Just as opportunities to receive federal funds could be missed if plans were not in place in time, money could also be squandered by letting construction contracts prematurely, when preliminary survey and design work was incomplete. Congress approved a series of three-year programs for national-park road construction in 1921, 1924, and 1927. Each new three-year program was much larger than the last. Furthermore, each program entailed a season of planning and survey work before road construction could be commenced efficiently. Thus, the appropriations process stamped Mount Rainier National Park's road development with a rhythm that did not necessarily correspond to local developments. The Rainier National Park Advisory Board tended to push for road contracts sooner rather than later, while the government engineers insisted on a more measured approach.

THE PROGRESS OF ROAD DEVELOPMENT

For the reasons outlined above, most of the park administration's road construction efforts focused on one road at a time, while the overall picture of road development changed from year to year. Superintendent Peters provided Mather with a three-year plan in 1922, and Tomlinson did the same in 1925, while Albright took a close interest in park road planning at the end of the decade. To follow the shifting components of these plans would be confusing and repetitious. This section traces the development of each of the park's roads separately but in the political context outlined above.

Nisqually Road

The road from Nisqually Entrance to Paradise continued to be a priority item in the national park budget throughout this era. As completed by the War Department in 1915, the road narrowed to a one-lane road above Narada Falls. Rangers manned checkpoints at either end of the one-lane section, where they restricted traffic first to one direction and then the other throughout each day. [8] By 1920, the checking system was creating a severe bottleneck. To make matters worse, when the limited amount of parking space at Narada Falls and Paradise filled up, visitors simply pulled off along the edges of the road. Even before road funds could be expended to open up other corners of the park, it was thought that this road must be widened and improved and parking spaces made to alleviate the congestion. [9]

Modest appropriations allowed the Park Service to make only piecemeal improvements on the road from 1916 to 1921. In 1921, the park's budget was significantly enlarged to allow more extensive improvements to the Nisqually Road, as well as construction of the Carbon River Road. [10] It was decided to build a second road between Narada Falls and Paradise, with the original road to be used for uphill traffic and the new road for downhill traffic. The new road was opened to the public on June 25, 1924. [11]

Passage of the National Park Highway Act of April 9, 1924 led to a second round of construction on the Nisqually Road beginning in 1925. Now the emphasis was on surfacing and widening the existing road, improving the bridges, and increasing the available parking at Paradise. New bridges, mostly built in a rustic style that was intended to harmonize with the landscape, included the lovely, stone-faced, arch bridges at Narada and Christine falls. [12]

Carbon River Road

It had long been assumed that the northwest corner of the park should be developed next after the southwest corner. Not only did the Carbon River area lie closer to Seattle than the southwest section of the park, but it was suggested from time to time that the Northern Pacific Railroad Company might be interested in developing the area. Furthermore, the steep north face of Mount Rainier, the broad alpine parks and dense lowland forests that were characteristic of the north side, and the impressive Carbon Glacier terminus made the area perhaps the most scenically grand in the park. What made the Carbon River Road so problematic was the fact that no access road existed between the town of Fairfax, where the Northern Pacific's branch line terminated, and the park boundary. Nearly half of this stretch lay across privately-owned timber land, and the remainder traversed the national forest. To develop the whole length of road required the cooperation of the NPS, the Forest Service, Pierce County, Washington state, and the land-owning timber company. It proved to be an unwieldy enterprise. That this corner of the park is even today the least developed is proof that the evolution of the park's road net was influenced to a large extent by the development of access roads outside the park.

From the first, the divided land ownership leading up the Carbon River made this project a tangle of local politics. Outside the park, the Manley-Moore Lumber Company had a logging railroad some distance up the valley beyond Fairfax, but the only public access as far as the park boundary was a horse and foot trail. Inside the park, the Washington Mining and Milling Company had built some three miles of wagon road along the Carbon in 1907, but as the road was never extended down to Fairfax it quickly fell into disuse and became overgrown. In 1915, a road survey was made of the route from the northwest corner of the park to Carbon Glacier, and it was estimated that the seven-mile stretch of road would cost about $100,000. [13]

Superintendent Toll and Mather urged construction of this road in 1919 and 1920, but Congress was unwilling to commit funds to new road construction in the park until the access road from Fairfax was under construction. During the early part of 1921, several conferences were held to get public and private funds dedicated to this project. Irving Clark of The Mountaineers and Asahel Curtis of the Rainier National Park Advisory Board pressed Forest Service officials to begin work on the three-mile section across the national forest, and the two lobbied Pierce County's board of commissioners to authorize construction of the few miles out of Fairfax. [14] The Natural Parks Association of Washington, founded with Mather's encouragement two years before, went into action to save the roadside timber from Fairfax to the park boundary; with "fine public spirit," reported Mather later that year, the Manley-Moore Lumber Company pulled out its railroad and logging equipment in exchange for timber contracts elsewhere. [15] Meanwhile, Mather urged the Northern Pacific to improve the plan of the gateway town of Fairfax in preparation for the automobile traffic. [16]

As a result of this combined effort, Congress appropriated $150,000 for Mount Rainier National Park in 1921—an "epoch making" sum in the jubilant words of Mather. Construction of the Carbon River Road began that summer and continued over the next three years. In 1924, Superintendent Tomlinson reported that the contractor had completed the road to within one mile of the glacier terminus, though the last three miles were one-lane. Flooding of the Carbon River had damaged portions of the road, however, and some revetment work was required. Moreover, Pierce County's road builders had left about one mile of road uncompleted. For these reasons, visitor use of the Carbon River Road remained light. In 1925, the NPS's chief engineer, George Goodwin, recommended that the NPS focus attention elsewhere as long as Pierce County fell short of completing the access road. [17] At the end of this era, the Carbon River Road remained relatively primitive.

White River Road

In contrast to the Carbon River area, where the need for development of an access road outside the park actually retarded roadwork inside the park, eastside development was pushed along by road development outside the park. The outside road in this case ran up the White River Valley to Cayuse Pass, then over Chinook Pass and down the American and Naches rivers to Yakima. The state road was some fifteen years in construction. The section of the road through the national forest and national park would later be designated State Route 410 and the Mather Memorial Parkway. The construction of this highway between 1916 and 1931 had a large influence on the timing and placement of the White River, Yakima Park, and Eastside roads. The first of these new park road developments was the White River Road.

Prior to 1916, the Mount Rainier Mining Company had built a wagon road up the south bank of the White River. Reaburn described this existing road in his annual report for 1916:

It follows practically the water grade of White River, which runs from 2 1/2 per cent in the lower sections to 13 1/2 per cent at the extreme upper end. Only one or two short sections are over 11 per cent. It is a single track wagon road, graded to a uniform grade, 12 feet wide inside of ditches. The bridges and culverts are 16 feet wide and are well constructed. A considerable portion of the road has been surfaced and the company is now operating an auto truck over it. [18]

Intrepid motorists began bumping up this road as early as 1918. They found the road impassable due to washouts and slides in 1919, but back in service the next year, when State Route 410 was completed as far as the park boundary. (Prior to the extension of the park boundary eastward to the Cascade Crest in 1931, this road remained outside the park; the White River Road, taking off where the White River Valley angled toward the mountain, entered the park near the site of the present-day White River entrance station.) In 1921, the Rainier National Park Company opened its White River Camp approximately seven miles inside the park boundary. In 1924, the NPS relocated part of the road away from the edge of the river to reduce the problem of flood damage. Meanwhile, the last three miles of wagon road up to Glacier Basin were allowed to revert to the condition of a trail. With the development of the Yakima Park area in 1929-31, all but the last mile of the White River Road became part of the new road to Sunrise. [19]

|

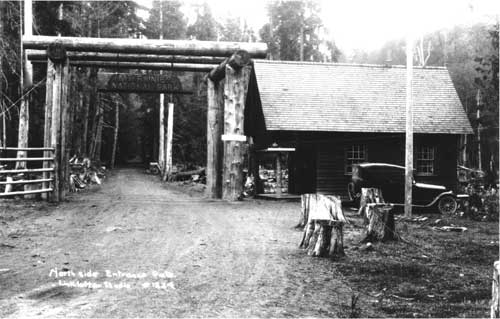

| Ranger station and entrance arch on the White River Road. (Lloyd G. Linkletter photo courtesy of University of Washington, Negative No. UW7935) |

Westside Road

Once public roads had been built into the southwest, northwest, and northeast corners of Mount Rainier National Park, the NPS began to lay plans for the first connecting road, a "westside road" that would begin just inside the Nisqually entrance at Tahoma Creek and extend north to the Carbon River Road. It was believed that the Westside Road would allow motorists starting from Seattle or Tacoma to make a loop through the park and take pressure off of the Paradise area. It would open up the rugged backcountry on the west side of the park. Though the road would be expensive to engineer, it would be one of the "scenic highways of the world." [20] Finally, it would be the first leg in an eventual around-the-mountain road. [21] Such was the original conception of the Westside Road.

Like the Carbon River Road, the history of the Westside Road was one of steadily diminishing expectations. The root of the problem, once again, stemmed from the inadequacy of state or county support for access roads to the northwest corner of the park. But in this case, the problem was compounded by the rugged topography along the intended route and the formidable cost of the park road itself. Before construction even began, it was decided that the anticipated route over Ipsut Pass between Mowich Lake and the Carbon River was too steep to be practicable. [22] Instead, the Westside Road would leave the park west of Mowich Lake, descending via another county or state access road to the town of Fairfax. This preserved the idea of a scenic loop drive originating somewhere near Tacoma and Seattle, but it placed a greater burden on the state or county to build that second road out of Fairfax. Still another factor that worked to undermine the original conception of the Westside Road was that soon after it was put under construction in the mid-1920s, the idea of an around-the-mountain road was superseded by the thought that the north side of the park should be kept roadless. [23] For all of these reasons the Westside Road was never completed beyond the North Puyallup River.

Park promoters began discussing the Westside Road as soon as funds were dedicated to the Carbon River Road in 1921. With passage of the National Park Highway Act of 1924, the Rainier National Park Advisory Board and other groups immediately began lobbying for a sufficiently large allocation of funds to Mount Rainier National Park to pay for this ambitious project. It was argued that the government must build the Westside Road in order to "keep faith" with the people of Washington state, who had invested more than $7 million in access roads to the park. [24] This distorted the situation somewhat, since most of that investment had gone to the highways leading to the southwest and northeast corners of the park, not to the northwest corner. But the fact remained that federal officials had long stressed the need for cooperation between state and federal road building efforts. "If it can be shown to the people of Washington that the building of the road up the Carbon River will be a start toward the proper development of a road around the mountain," Mather advised Curtis in 1921, "I am sure they will see the necessity of cooperation. If we have a completed road to the Carbon Glacier in the next two years we will have a strong argument for the highway link around the west side of the mountain, but if this work drags out over several years it puts off the bigger work just that much longer." [25] Now that the Carbon River Road had been completed on schedule, park promoters insisted, it was time for the NPS to deliver on that promise.

Had it not been for this circumstance, NPS officials might have postponed and then cancelled the whole Westside Road project. Superintendent Tomlinson repeatedly expressed doubts that the route surveyed in 1922 was truly feasible. But the Rainier National Park Advisory Board pushed for a resurvey and demanded that the Westside Road be given top priority. On August 12, 1925, a conference took place at the Winthrop Hotel in Tacoma. Present were two NPS civil engineers, Burt H. Burrell and R.N. Kellogg, NPS Chief Landscape Engineer Thomas C. Vint, Superintendent Tomlinson, and Asahel Curtis and Herbert Evison representing the Rainier National Park Advisory Board. Working with a three-year allotment for the park of a little more than $1 million, Curtis and Evison prevailed on the NPS to revamp the budget so that nearly sixty percent of the road development funds would be allotted to construction contracts for the Westside Road. [26] Mather and Albright conferred with Burrell afterwards and agreed to resubmit the agency's budget estimates for Mount Rainier along the lines that the Advisory Board recommended. [27] Two weeks after the August 12 meeting, Curtis, Vint, two engineers with the Bureau of Public Roads, an NPS publicity agent, a cook, and a packer set out on a resurvey of the Westside Road, beginning with Ipsut Pass. [28] This was probably the most influential moment in the Advisory Board's career. Ironically, the decision to go full speed ahead with the Westside Road project was one that Albright would come to regret.

An interesting sidelight of this deliberation was its role in bringing about the formal transfer of road building that fall from the NPS to the Bureau of Public Roads. As early as the spring of 1925, the Rainier National Park Advisory Board was instrumental in putting NPS officials in touch with engineers in the Bureau of Public Roads to discuss the possibility of a resurvey. This was a sensitive negotiation, since it implied a lack of confidence in the NPS's own Engineering Department. Ostensibly, Chief Engineer George Goodwin opposed further development of the Westside Road for the time being because of the lack of cooperation he had received from Pierce County officials, but it was also true that the deliberations over the Westside Road were tending to highlight Goodwin's antiquated standards of road engineering. When he resigned that summer, there was no love lost between him and the Advisory Board. Indeed, when Mather formalized the new arrangement with the Bureau of Public Roads that fall, Asahel Curtis bluntly advised the director that it was the most important decision he had made in recent years. [29]

The first construction contract for the Westside Road was let in 1926. For the next three seasons, the route up Tahoma Creek and over Round Pass was the scene of a major construction effort, employing hundreds of men. Meanwhile, a location party, consisting of fifteen to twenty men, brushed a trail northward into the canyon of the South Puyallup River, around Klapache Ridge, into the canyon of the North Puyallup River, up through Sunset Park, and across the Mowich River to a "west entrance" near Mowich Lake. In 1927, the route was extended to Spray Park. [30] Only about half of the Westside Road would ever be built, though the whole design would figure in the park's first master plan in 1928.

At the end of this era, the Westside Road was opened to the public from its point of departure on the Nisqually road northward as far as Round Pass. The ostensible reason why this important route was not completed was the failure of the state of Washington to provide for an approach road from Fairfax to the "west entrance," making it difficult to work on both ends of the road at once. [31] Equally significant, however, was the high cost of construction over this route and the growing emphasis on eastside development instead.

Yakima Park Road

One of the first tasks assigned to the Bureau of Public Roads in Mount Rainier, after the relocation of the Westside Road route, was the surveying of a route from the White River up to Yakima Park. Superintendent Tomlinson's idea was to develop Yakima Park as an alternative destination point in the park and thus take pressure off of Paradise. Mather concurred in this plan, and requested the survey immediately in order to have the data available for the making of the next three-year development program, which would likely commence in 1928 or 1929. [32]

The development of Yakima Park was hailed as the most coordinated planning effort by the NPS and a park concessioner to date. No sooner would the road be completed than the physical plant would be in place and new hotel construction would be underway. In 1929, four separate road construction contracts were let on the Yakima Park Road, and while these were reaching completion during the following year, a power plant, water supply, and sewege system were installed at the new development site. NPS landscape architects were given unprecedented scope in working with engineers in the Bureau of Public Roads. They designed scenic turnouts, rustic guardrails, and handsome bridges. The bridge over the White River—a sixty-foot concrete arch with stone facing and railing and a four-foot bridle path—received special praise from the road engineers and the public. The wide-radius switchback at Sunrise Point, which featured parking on the inside of the horseshoe curve and pedestrian bays around the perimeter where visitors could get away from their cars and behold one of the most panoramic views in the park, was state-of-the-art. [33]

Stevens Canyon/Eastside Road

If park administrators saw road development as their best means of controlling visitor access and circulation, they were also quick to acknowledge that road development created new problems and administrative challenges. This paradox, inherent in all national park development, was acutely a feature of Mount Rainier National Park, where so much population lived within a half day's drive of the Pacific Northwest's most renowned scenic wonderland. The relationship of the Stevens Canyon and Eastside roads to the Yakima Park Road was a case in point. The Yakima Park development took pressure off of Paradise, but it also added to the administrative complexity of the park and necessitated a connecting road between the southwest and northeast corners of the park. Tomlinson described the new situation this way in 1930:

With the throwing open to automobile travel of the Yakima Plateau area in 1931 the administrative problems of the park will be doubled. There will be practically as much travel and as many activities in Yakima Park as there are now in Paradise Valley. Due to the great distance from park headquarters and lack of telephone or other rapid communication facilities it is essential that a full force of rangers, ranger naturalists, and other personnel be provided in order to protect the area and serve park visitors. The only means to reach Yakima Park from Longmire by automobile requires a detour of 135 miles over State roads. Being separated by this distance makes practically two parks as far as administration and operation are concerned. It is essential that construction work on the east side road be started at the earliest practicable date and prosecuted with the utmost dispatch so that a connecting road can be made available as soon as possible. On account of the physical difficulties to overcome, such a connecting road can not possibly be completed in less than six or seven years. By that time it is estimated that the travel to Yakima Park will have almost equaled the total number of visitors that now come to the park. [34]

It will be recalled that road surveys had been made across the southern side of the park as early as 1904 and again in 1915-16. The standards for road construction had changed so much during the 1920s that these past surveys were of no more than historical interest when the NPS took up the question of a suitable route in 1926. [35] Over the next five years, several surveys and reconnaissances were made of this large section of the park. Director Albright selected the eventual route in 1931.

There were two major topographical features that influenced the alternative routes. The first was the east-west trending Stevens Ridge and Stevens Canyon, which presented a stark choice between a traverse of the canyon wall or a "high line" along the top of the ridge. The second topographical feature was Cowlitz Divide, which ran north and south exactly athwart the remaining distance to Cayuse Pass. This presented another stark choice: either a right-angle bend to the south, necessitating a long dogleg out of the park around the end of this ridge; or a right-angle bend to the north, up Cowlitz Divide and through the broken highcountry surrounding Cowlitz and Ohanapecosh parks. Three routes in the latter direction were surveyed in 1927 and 1928. [36] At Albright's request, the longer route around the south end of Cowlitz Divide was surveyed in 1931. [37] The longer route to the south was the route that Albright selected. [38] The final location and construction of this road would be one of the major road developments of the 193Os.

Numerous factors weighed in Albright's decision. As the choice of routes essentially boiled down to a high line with spectacular views or a low line largely in forest, Albright had to weigh the scenic splendor of the high route against the lesser amount of scarring that the low route would entail, and the shorter season of the high route against the longer mileage of the low route. There was the additional complication that the low route necessitated a swing outside the park boundary into the national forest—or else a boundary extension to encompass the new road. Furthermore, the state of Washington planned to build a road up the Ohanapecosh River to join Naches Pass Highway (formerly called McClellan Pass Highway), and it was unclear when this would be built and how the park road could most advantageously tie in with it. Albright's choice of the lower, more circuitous route was linked in part to his successful negotiation with the Forest Service of a major boundary revision on the east and southeast edges of Mount Rainier National Park. It also signalled his growing sensitivity to charges that the national parks were becoming too cut up by roads. [39]

Paradise Scenic Road (Proposed)

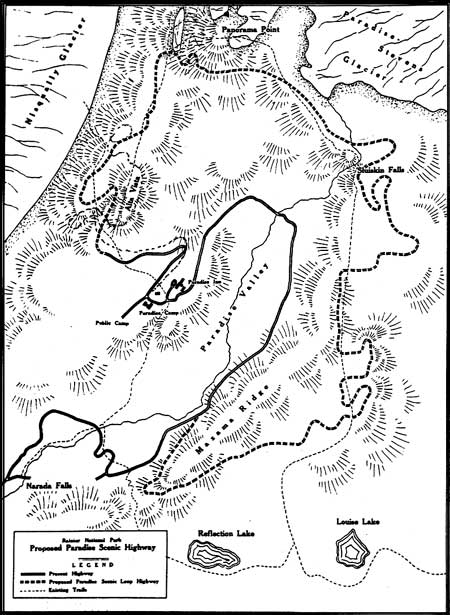

>While survey teams were investigating the possibility of a high road around the southeast flank of Mount Rainier, an even higher road was under consideration above Paradise. The idea was to build a one-way scenic loop road starting at Paradise, going up to Timberline Ridge at 6,300 feet, and ending on the south end of Mazama Ridge near the Reflection Lakes. Although the road would syphon away some traffic from the Paradise parking lot, it was not the road's main purpose to improve visitor circulation. Rather, its purpose would be to give automobile-bound tourists a better view of glaciers and alpine meadows. [40] The road proposal raised the philosophical question of just how far the NPS ought to go to accommodate that type of visitor use.

At Mather's request, Engineer R.N. Kellogg of the Bureau of Public Roads surveyed this route in the fall of 1927. [41] The full loop road was found to be impractical and the plan was scaled back to a two-way road from Paradise to Alta Vista. From the earliest mention of this road proposal, however, NPS officials were skeptical. Chief Landscape Engineer Vint thought the road was unnecessary; visitors could walk the one and a half miles to Alta Vista. Mather and Albright were inclined to agree. Only Superintendent Tomlinson thought it was a good idea. [42]

|

| Proposed Paradise Scenic Highway |

RNPC officials held out for the scenic 1oop road, visualizing the tours that they would provide around it. The company's president, H.A. Rhodes, hinted to Mather that the construction of the new Paradise hotel depended on it. He was "keenly disappointed" when Mather first disapproved the project in 1928. Rhodes wrote to the director:

Without this means of convenient access to the Glacier Rim the general public, many thousands of people on week ends and holidays, will swarm down upon the new hotel location and destroy the relative seclusion that is sought for in choosing this site. Without this route, intended for use of the general public, seventy-five per cent of Park visitors are denied opportunity to witness the marvelous spectacle to be enjoyed only from a location at the Glacier Rim. [43]

Rhodes also wrote to Congressman Louis C. Cramton of Michigan, a staunch friend of the national parks, for support on this issue.

After 1928, the scenic road proposal was eclipsed by developments elsewhere, particularly in Yakima Park. When the RNPC abandoned its plans for a new hotel at Paradise, settling instead for the more modest Paradise Lodge, it did not press as hard for this road. Still, as late as 1931, Albright had not rejected the project. The Bureau of Public Roads made another location survey, while the NPS made an independent preliminary survey of a different location. The latter entailed a steeper grade but made use of the more scenic north side of Alta Vista. Albright's thought at this time was to build a low-standard road using NPS labor on force account. However, this project was never carried out. [44]

DESIGNATION OF A WILDERNESS AREA

The large amount of public debate on the development of roads in Mount Rainier National Park gave rise to concerns that the NPS was going too far in opening the park to automobile use. These concerns came to a head in a resolution adopted by the Board of Trustees of The Mountaineers in April 1928. The Mountaineers' resolution asserted that the present road program "would subject approximately three fourths of the park to commercial use and development and retain only one fourth in its natural wilderness condition." Superintendent Tomlinson took issue with that characterization of his road plan, but he nevertheless endorsed The Mountaineers' proposal to have a certain portion of the park formally declared a "wilderness area." He suggested to Mather that "such action would be in entire accordance with national park policies and ideals, and it would have the effect of assuring those concerned with the preservation of natural wilderness areas that the National Park Service is guarding against over development of the national parks." [45]

The Mountaineers' resolution caused some perplexity among senior NPS officials in Washington, D.C. (Mather was then out West; Arno B. Cammerer and Arthur E. Demaray were left to ponder the proposal in his absence.) Demaray informed Tomlinson that the NPS had one precedent for a "wilderness area." Approximately seven square miles had been set aside for scientific study in Yosemite National Park. Within that designated area no camping, fishing, or domestic animals were permitted; access was only allowed for the purpose of scientific study or for necessities of administration. This wilderness area had been set aside in November 1926 at the request of Dr. C. Hart Merriam, President of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, and its principal purpose was for research. Obviously, that was not the intent of the resolution by The Mountaineers.

The Mountaineers seemed to desire that an area be reserved from all road and commercial development and made available for the sole use of those on foot or horseback. Demaray and Cammerer recommended that "wilderness area" was therefore the wrong term; rather, it should be designated on administrative maps as "to be free from road and commercial development." Demaray requested a map from Tomlinson, showing the area that he thought should be so administered. [46]

Tomlinson duly sent a map with areas marked for wilderness or roadless designation. He pointed out that The Mountaineers had consented to the proposed developments at Yakima Park and Spray Park, but wanted all the lands lying north of these places preserved in a wilderness condition. "I suggest that the areas be described as follows," Tomlinson wrote. "'That all of the territory in Mount Rainier National Park lying north of Berry Peak, Ipsut Pass, Spray Park, Mystic Lake and Yakima Park' and the areas known as 'Klapatche Park, St. Andrews Park and Indian Henry's Hunting Ground' are to remain free of road, hotel, pay camps and all commercial development." Tomlinson pointed out that by designating these areas as roadless, the NPS would definitely have The Mountaineers on board for developing Yakima Park and Spray Park. [47]

In August, Mather returned to Washington, D.C. and took the opportunity to consider the proposal by The Mountaineers and Superintendent Tomlinson himself. The director approved the plan in its entirety, subject to the understanding that the wilderness designation did not bar the development of trails. [48] The only thing that The Mountaineers did not obtain was the official approval of the Secretary of the Interior. Time would show that that further guarantee was not necessary.

TWO BOUNDARY REVISIONS AND THE MATHER MEMORIAL PARKWAY

Congress passed laws in 1926 and 1931 that modified the boundaries of Mount Rainier National Park. In both cases, the new boundaries were extended outward from the original township lines to conform to natural features (the Nisqually, Carbon, and White rivers in the 1926 law, the Cascade Crest and the summit of Crystal Mountain in 1931). The main purpose of these boundary revisions was to bring park roads completely within the jurisdiction of the park.

Boundary Change of 1926

The problem was most pronounced in the case of the Nisqually Road, which followed the general course of the Nisqually River from the park entrance to Longmire, meandering across the south boundary of the park in two places. Technically, the NPS did not have authority to maintain these two short sections of road. As early as 1913, Superintendent Ethan Allen had called attention to the need for a modest boundary adjustment to correct this problem, but nothing came of it. [49] The problem was quietly overlooked for a dozen years until a good opportunity arose to push for a boundary adjustment.

In 1925, Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work formed the Coordinating Committee on National Parks and Forests to consider a whole package of land exchanges between the NPS and the Forest Service. As was the case with most national parks, additions to Mount Rainier National Park would be made at the expense of the surrounding national forests. Indeed, most of the national parks were created from national forest lands (beginning with Mount Rainier in 1899). This circumstance had made the Forest Service increasingly jealous of the NPS. Secretary Work's committee was formed in order to force NPS and USFS officials to reach an accommodation. The NPS was invited to make a comprehensive proposal for new national parks and boundary adjustments that involved national forest lands, and the committee would either reject or endorse the recommendations before submitting them to Congress. [50]

As part of this initiative, Mather requested Superintendent Tomlinson's views on possible boundary changes for Mount Rainier. Tomlinson recommended that the eastern boundary be adjusted to follow the Ohanapecosh River, Chinook, Dewey and Klickitat creeks, and the White River. Noting that the state of Washington proposed to build a highway from Cayuse Pass southward along these water courses, the superintendent suggested that "it might be well to consider this with regard to road development." [51] In addition, Tomlinson recommended extending the boundary to the Nisqually River in the southwest corner of the park and to the toe of Cowlitz Divide in the southeast corner of the park—the latter extension to include Ohanapecosh Hot Springs. Tomlinson had conferred with Forest Supervisor E.J. Fenby on these proposals and Fenby had expressed himself in favor of the boundary adjustments, but had cautioned Tomlinson that others in the Forest Service might object to the eastside additions. It is unclear whether Mather had any discussion of this with Forest Service officials, but in his final proposal to the Coordinating Committee, he asked for adjustments along the Nisqually, Carbon, and White rivers and the addition of a mere half section in the southeast corner to take in Ohanapecosh Hot Springs.

In August and September 1925, the Coordinating Committee made an inspection trip of several areas in the Rocky Mountain region which Mather had recommended for inclusion in the national park system. The committee endorsed the relatively modest boundary changes at Mount Rainier without personally visiting the area because the Forest Service raised no objection to them. Since other proposals, notably Mather's proposal to create a Grand Teton National Park, did arouse strong opposition from the Forest Service, the various boundary changes were introduced as separate bills in Congress the following spring. [52]

Meanwhile, local opposition had built up in Lewis County toward the inclusion of Ohanapecosh Hot Springs. Evidently the opposition was organized by Dr. Albert W. Bridge, owner of a small hotel and mineral baths which he operated under Forest Service permit. Bridge convinced the Lewis County Commission and a number of local newspaper editors and civic organizations that the boundary adjustment was a plot by the Rainier National Park Company to drive out its competition. Bridge was able to capitalize on Lewis County residents' feeling that Seattle and Tacoma business interests were monopolizing the national park tourist trade. [53] After Representative Albert Johnson of Washington brought this local opposition to the attention of the House Committee on Public Lands that May, Mather agreed to drop his request for the half section and leave Ohanapecosh Hot Springs outside the park for the time being. The amended bill was passed May 28, 1926. [54]

Boundary Change of 1931

The second boundary adjustment involved considerably more land area. It extended the east boundary of the park to the summit of Crystal Mountain and the Cascade Crest. This made better sense than a line following rivers and creeks, both from the standpoint of managing wildlife populations and protecting scenic vistas. But again it was the developing road grid around Mount Rainier that prompted the boundary change. When Director Albright broached the issue with Chief Forester R.Y. Stuart in 1930, the state highway over Chinook Pass was less than a year from completion. Albright listed the following reasons for the extension of the park:

1. Chinook Pass was the natural eastern gateway to the park. It would make a spectacular entrance to the park at a place where the NPS could meet all incoming visitors and provide them with information.

2. The region between Chinook Pass and the present park boundary was naturally tributary to the pass and could best be patrolled and protected from the park.

3. A small section of the Cascade Crest would enrich the scenery of the park, vary its natural features, and increase its educational opportunities.

4. Cayuse Pass, below Chinook Pass, was a central point for all roads east of the present park boundary. The NPS proposed to build a new road up the Ohanapecosh River to join the state highway at Cayuse Pass.

5. The NPS could not build this road unless some boundary adjustment were made. There was no other feasible route for the road.

6. A proposed camp development at Tipsoo Lake just west of Chinook Pass, or at Cayuse Pass, would seriously impair the investment being made at Yakima Park. Gasoline stations or refreshment stands at these strategic points would blot the landscape.

Albright noted that the NPS could not justifiably charge a park entrance fee for through traffic on the new state highway, but pointed out that this matter could be handled in the bill to revise the park boundary. He closed his letter to Stuart by asking that the Forest Service forebear issuing any special use permits covering land in the extension area pending a final determination of the boundary. [55]

The Forest Service cooperated with the NPS proposal and the legislation was whisked through Congress expeditiously. The Act of January 31, 1931, gave the NPS all that it had asked for, including Ohanapecosh Hot Springs and most of the southern end of Cowlitz Divide, around which the Eastside Road would be located. Section 2 of the act contained a proviso, "that no fee or charge shall be made by the United States for the use of any roads in said park built or maintained exclusively by the State of Washington." [56]

Only one year after this boundary extension, NPS biologists would recommend further additions to the park based on ecological considerations. These would not go through. The boundary adjustments in 1926 and 1931 did benefit the park from an ecological standpoint. But this was almost as much by luck as by design. It was the lay of the land for purposes of road development that finally shaped the configuration of the park's boundaries.

The Mather Memorial Parkway

The desire to bring road development and land use into harmony led to one other significant land action at the end of this era. The aim of the Mather Memorial Parkway was to protect scenic values—to set aside a one-mile-wide, seventy-five-mile-long strip of land along the new Naches Pass Highway so that the scenic drive over the Cascades would be protected from the visual effects of logging. The creation of the Mather Memorial Parkway is part of the history of Mount Rainier National Park's road development, but it involved the protection of roadside timber leading to the park rather than new road construction in the park. The designation of the Mather Memorial Parkway is part of the history of Mount Rainier National Park's boundaries, too, but two secretarial land orders rather than an act of Congress were all that were required to accomplish it.

Mather conceived the idea of a "Cascade Parkway" during a visit to Mount Rainier in July 1928 when he was looking over the proposed Yakima Park development. The Naches Pass Highway was then nearing completion. It would connect Yakima with Seattle and Tacoma via Chinook Pass and the White River Valley. Mather anticipated that the completed highway would bring large numbers of visitors to the northeast corner of the park, especially with the construction of a new road up to Yakima Park. He wanted the scenic approaches to the park—either up the White River Valley or over Chinook Pass—to be protected. He broached the idea of a Cascade Parkway with Asahel Curtis and Herbert Evison, the latter a Washington state resident and close collaborator of Mather in the National Conference on State Parks. Both Curtis and Evison were enthusiastic. [57]

The creation of a parkway would involve two main land owners: the U.S. Forest Service and the Northern Pacific Railroad Company. In addition, there were a number of summer homesite owners in the national forest who would have to be brought on board. Mather first took his request to the most problematic of these land owners, the railroad. He met with the president of the railroad, Charles Donnelly, in Yellowstone on July 24, 1928. Mather described the impending development at Yakima Park and suggested that the Northern Pacific might be able to work something out with the park concession—perhaps run its passengers through Mount Rainier National Park by bus, taking them off the train in Yakima and reboarding them in Tacoma. He then explained that he wanted to preserve the timber along this scenic highway, and suggested that the Northern Pacific might dispose of its timber holdings in this area by exchange or donation. Donnelly was non-committal. [58]

That fall, Curtis and the Rainier National Park Advisory Board launched a publicity campaign to save the timber along this highway. They had hoped for a return visit by the director, but Mather suffered a stroke enroute in November and had to be hospitalized in Chicago. According to Albright, several top NPS officials who visited Mather at his bedside shortly after his stroke attested to the fact that their fallen leader mumbled over and over with great determination the word "Cascade." Albright finally deduced that Mather was referring to the Cascade Parkway in Washington. [59] It was the one unfinished piece of work that most troubled him.

Mather's good friend Herbert Evison, who was actively involved in the Cascade Parkway project, corroborated Albright's story. "When I visited Mr. Mather at the hospital in Chicago," Evison wrote, "his first question concerned the parkway plan; he was keenly interested in knowing what sort of reception the people of the state had given it; delighted that the Forest Service was cooperating by setting aside the needed lands inside the national forest; and intensely pleased at the prominence given the project by the newspapers." [60] Evison would use this story to great advantage in advancing the Cascade Parkway project.

A few weeks after his stroke, it became clear that Mather was permanently disabled. Albright succeeded him as the second director of the NPS on January 12, 1929. Mather died a little more than a year later on January 22, 1930. Two days after Mather's death, Evison met with prominent conservationists in Washington, D.C. to discuss the Cascade Parkway. Franklin Adams, chairman of the Mather Memorial Appreciation Committee, was at the meeting. Evison proposed to set up the parkway project as a memorial to Mather, and wanted the committee's endorsement." [61] A few days later, he wrote to the committee that he was strongly opposed" to the memorialization of Mather with any kind of "man-made structure," for he could imagine "nothing more unsuitable to this lover of trees and of the beauty and grandeur of the American out-of-doors." Instead, Evison insisted, Mather deserved "a memorial that is living and will live as we are sure the memory of the man and his works will live." [62] Evison finally got what he wanted: the committee's blessing, and its valuable financial assistance as well.

By then the project had garnered an impressive list of supporters: Superintendent Tomlinson, the Forest Service's Recreational Examiner J. N. Cleater, District Forester C. M. Granger, and Forest Supervisor E. J. Fenby. [63] To this official roster could be added the White River Recreational Association—homesite owners who had formed their own association and affiliated with the Rainier National Park Advisory Board. [64] With passage of the Act of January 31, 1931, twelve miles of the proposed parkway now came within the boundaries of the national park. The parkway therefore required secretarial orders from both the Agriculture and Interior departments. On March 26, 1931, Secretary of Agriculture Arthur M. Hyde issued a land classification order which set aside a strip of land fifty miles long and half a mile wide on either side of the Naches Pass Highway, which was designated the Mather Memorial Parkway. On April 23, 1931, Secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur signed a similar order for the twelve miles of road through the northeast corner of the park. The land was dedicated to the scenic and recreational enjoyment of the public. [65]

The parkway was formally dedicated on the morning of July 2, 1932. On hand for the ceremony were Asahel Curtis, Superintendent Tomlinson, Governor Roland H. Hartley, and Professor Edmund S. Meany. A bronze plaque, donated by the Stephen T. Mather Appreciation Committee, was unveiled by the governor. Due to an unusually deep snowpack that year, the plaque could not be placed in its permanent stone foundation on Chinook Pass, but Tomlinson had a temporary stand on hand for the unveiling. When the snow melted off later that season, the plaque was mounted on a boulder "in a beautiful grove of mountain trees more than a mile above the sea and under the shadow of old Mount Rainier." [66]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap8.htm

Last Updated: 24-Jul-2000