|

MOUNT RAINIER

Wonderland An Administrative History of Mount Rainier National Park |

|

| PART THREE: YEARS OF PROMISE, 1915-1930 |

VII. MISSION AND PROFESSIONALIZATION

INTRODUCTION

With the establishment of the National Park Service in 1916 a new era began in the history of Mount Rainier National Park. The park ceased to be a separate entity under the loose supervision of the Secretary of the Interior, becoming instead a unit in a system under the direct control of park professionals.

Prior to 1916 there had been some semblance of a national park system as the legislative acts creating the several national parks bore strong similarities and put all the parks on roughly the same footing. But preservationists began to argue the need for a separate national parks bureau to strengthen the parks' administration. The Sierra Club, the American Civic Association, the National Geographic Society, and numerous other groups campaigned for the new bureau. Secretaries of the Interior Walter L. Fisher and Franklin K. Lane strongly supported the measure, and called interested citizens together for a national park conference nearly every year beginning in 1911. Congress finally responded to public demand by passing the National Park Service Act on August 25, 1916. The National Park Service Act led to the professionalization and esprit de corps of a park service, an end to stopgap administration of some parks by the Army, and a significant growth in park appropriations. Historian Donald C. Swain has stated that the campaign for this legislation marked the emergence of the aesthetic conservationists, or "preservationists," as a countervailing influence to Pinchotism and an effective, organized force within the national conservation movement. [1]

Another factor which distinguished these years as a distinctive era in the history of the park was the forceful leadership of Stephen Tyng Mather, who served as the first director of the NPS from 1916 to 1929. Mather had the support of a highly competent assistant director, Horace M. Albright, who would succeed him as the second director of the NPS from 1929 to 1933. Both Mather and Albright took a keen interest in the administration of Mount Rainier National Park—more than subsequent NPS directors, with the possible exception of Conrad L. Wirth. Mather personally directed the reorganization of the park concessions in 1916, while Albright involved himself deeply in the planning process in Mount Rainier National Park in the late 1920s. More than in the previous era, Mount Rainier park policy was made in Washington, D.C. by the men at the top: Mather, Albright, and the expert landscape architects whom they had on their staff.

Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane recruited Stephen T. Mather to work for the national parks. Mather had no prior experience in government. He was a self-made millionaire, philanthropist, and mountain enthusiast. He and Secretary Lane were old acquaintances from Mather's college years in California. In the fall of 1914, Mather wrote to Lane complaining about the administration of the parks. Lane was sympathetic toward the demand for a national parks bureau, but he needed someone who was a good organizer and promoter to take the matter to Congress and the people. He replied to Mather: "Dear Steve, If you don't like the way the national parks are being run, come on down to Washington and run them yourself." [2] It took some further arm-twisting before Mather accepted an appointment as Assistant to the Secretary in January 1915, and then some additional cajoling to convince Mather to become the first director of the NPS nearly two years later.

Mather promised to build a strong national park system. He developed high standards by which new national park proposals were judged before they were recommended to Congress. He pursued worthy park proposals aggressively and deflected numerous others into the state park movement instead. He wanted to expand the national park system by adding new units that possessed superlative scenic and scientific values or were representative of a distinct geological or biological phenomenon, but he did not want redundancy. For this reason, Mather rejected proposals to create national parks around Mount Hood or Mount Baker, since Mount Rainier already served as the superlative example of a Pacific Northwest volcano; but he supported the addition of three other new units featuring recently active volcanoes (Hawaii and Lassen Volcanic national parks in 1916, and Katmai National Monument in 1918). [3]

Mather promised as well to create a model agency for administering the national parks. Mather's idea of a model agency was one that would be tightly focused on its mission of park development and protection. Whenever possible, he pledged, the NPS would secure technical assistance from other agencies in the federal government rather than duplicate their capabilities in another bureau. The NPS would turn to the Biological Survey for help with floral and faunal inventories and predator control, to the Geological Survey for topographic work, to the Public Health Service for sewer- and water-system planning and construction, to the Bureau of Entomology for insect control. In all, Mather named thirty-six agencies that the NPS could tap for technical help. At the same time, the NPS would develop two areas of expertise that were unique in the federal government: park landscape engineering and interpretation. The agency's tight focus would allow park administration to be lean and efficient. It would foster esprit de corps. Ten years after commencing his work for the government, Mather could write: "I believe that today the National Park Service is a model bureau from the standpoint of efficiency in expenditure of public monies, adherence to the federal budget system, individual output of employees, cooperation with other government bureaus, low overhead expenses, and high morale and public spirit of personnel." [4]

This chapter looks at how the administration of Mount Rainier National Park evolved from 1916 to 1929, when Mather was director of the NPS. The first section of the chapter looks at the organization and growth of the park staff, the park administration's use of expertise based outside the park but inside the NPS, and improvements in staff housing and working conditions which tended to enhance employee morale. The second section examines the beginnings of the NPS interpretive program in Mount Rainier National Park. The third section considers various natural resource issues for which the park administration sought expert guidance from other federal agencies.

ADMINISTRATIVE ORGANIZATION

During the seventeen years of park administration under the Secretary of the Interior, Mount Rainier National Park had acquired its own superintendent, a staff of two or three permanent rangers, and an additional force of rangers during the tourist season. Beginning with his appointment as Assistant to the Secretary in 1915, Mather began to make changes in the park's administrative organization either directly or through his superintendents. These changes were evolutionary. Taken altogether, they revealed a definite trend toward professionalization.

Superintendents

In the early years, park superintendents had reported directly to the Secretary of the Interior. From 1914 to 1916, park "supervisors" had reported to a superintendent of national parks, who in turn answered to the Secretary of the Interior. Beginning a few months after passage of the National Park Service Act, park "supervisors" resumed their earlier title of park "superintendents," and reported to the NPS director. [5]

The first change that Mather sought in the administration of parks was in the quality of superintendents. Prior to 1915, the national parks were staffed according to the spoils system: when Republicans or Democrats won an election, park superintendent jobs were dispensed as gifts to the party faithful, often without regard to the qualifications of appointees. When Mather traveled to the many parks in 1915, he found good superintendents and bad. He was particularly displeased with the recently appointed superintendent at Mount Rainier, John J. Sheehan. He replaced Sheehan with DeWitt L. Reaburn, a topographic engineer from the Geological Survey. Reaburn demonstrated competent administrative ability over the next three years. After Reaburn came Roger W. Toll, a Columbia University-trained engineer, charter member of the Colorado Mountain Club, and former major in the Army during World War I. Mather recruited Toll in 1919. He served as superintendent at Mount Rainier for sixteen months, his first tour of duty in what turned out to be a stellar career with the Park Service. After Toll, Mather handpicked two more civil engineers: William H. Peters, who transferred to Mount Rainier from Grand Canyon National Park in 1920, and Clarence L. Nelson, who had many years of experience with the Geological Survey. These four men were typical of Mather's superintendents; he preferred men with road-building or engineering expertise to training in the biological sciences. He wanted government career men; he got most of his recruits from the Geological Survey and the Army.

Mather's last appointee to Mount Rainier was a military man and another auspicious choice. Mather met Owen A. Tomlinson in Reno, Nevada, where he was in charge of a station in the new U.S. Air Mail Service. Tomlinson had proven his executive ability during twenty years of service in the Philippines. There he had risen to the rank of major in the Filipino constabulary overseeing a variety of public works from mountain trails to bridges, buildings, and irrigation projects. [6] Mather persuaded Tomlinson to become superintendent of Mount Rainier National Park in 1923. Tomlinson remained there for eighteen years, and continued to have a hand in the park's administration as director of the Western Region for nearly ten years after that.

These strong appointments notwithstanding, Mather expected his superintendents to defer to himself and his assistants on important policy matters. The director and his assistant directors, especially Horace M. Albright and Arno B. Cammerer, took a much closer interest in policy issues at the park level than any Washington-based Interior officials had done prior to 1916. Mather, Albright, and Cammerer all made numerous visits to Mount Rainier and the Puget Sound cities. Most sensitive or precedent-setting issues were resolved at the top administrative level, as Mather and his assistants sought to develop system-wide policies and standards. Thus, the superintendent became more of a policy advisor than a policy maker in this era. On the other hand, the superintendent administered a larger budget, managed a larger park staff, and enjoyed more technical assistance from engineers and landscape architects than before. On most routine matters, the superintendent could act with greater discretion and self-assurance than was possible when the superintendent had been directly responsible to the Secretary of the Interior.

Rangers

Mather inherited a national-park ranger force that had already been several years in the making. Following in the tradition of the Forest Service, the original park rangers at Mount Rainier were local men whose main job qualifications were that they were competent woodsmen and could tolerate primitive housing arrangements. Most of the early hires at Mount Rainier continued in the job for more than one year; some, such as Sam Estes and Tom O'Farrell, stayed on the park staff well after the establishment of the Park Service. [7]

Shortly before Mather joined the Department of the Interior, Secretary Lane's first superintendent of national parks, Mark Daniels, drafted a set of regulations defining the qualifications and duties of the park ranger. The regulations provided for a standard uniform and called for rangers to write monthly reports of their activities. Rangers had to be between twenty-one and forty years of age, of good character, physically fit, and tactful in handling people. They had to have a common-school education, be able to ride and care for horses, know how to handle a rifle and pistol, and have some knowledge of trail construction and fighting forest fires. Mather approved the regulations and distributed them to all the parks. [8]

But this was only a start. Mather wanted to create a professional ranger force. He wanted to attract young men to the service who would think in terms of permanent careers. He sought to raise educational standards, to introduce entrance examinations, and to facilitate the transfer of rangers from park to park. [9] Even before these standards could be bureaucratically instituted, park superintendents sought to professionalize the ranger force along the lines Mather had in mind. Mount Rainier, like other parks, began to employ college students during the summer months, and gradually to work them into the service on a full time basis. The college students tended to be idealistic and resourceful. Often they brought to their job a knowledge of natural history which could be shared with the park visitors. The following excerpt from a letter by Superintendent Clarence L. Nelson to Chief Engineer George E. Goodwin illustrates this process.

We also have a new ranger whom I feel we should care for. He has graduated in forestry and park administration from the University at Syracuse, New York, and has proved very competent here at Longmire this Summer. He is a type of man rare in the Service, and one who should be encouraged in every way to remain. His nature lectures in our public camp ground at Longmire have had the hearty approval of our visitors here. He has also been quite willing to do the trail work and other manual labor whenever it was necessary. His name is Floyd W. Schmoe. [10]

Schmoe became Mount Rainier's first park naturalist in 1924 and served in that year-round position until 1928.

The early park rangers had to do a little of everything, for the ranger force constituted practically the whole park staff. They performed backcountry patrol, traffic control, entrance fee collection, road maintenance, building and trail construction, fire-fighting, predator control, clerking, and search and rescue. Beginning in 1921, park rangers began to give guided nature walks and to provide information to the public. As the park staff grew, more specialization was possible. In 1922, the park superintendent had a chief clerk and four permanent rangers; during the summer season this force was augmented with fourteen seasonal rangers, two clerks, two telephone operators, and a labor force for construction and maintenance of roads and trails. [11] By the end of the decade the permanent staff had increased from six to eighteen employees, while the summer hires had increased to sixteen rangers and three ranger-naturalists. The seasonal road crew now numbered 140 men. [12]

The NPS ranger force achieved a high level of esprit de corps by the end of the Mather years. With their distinctive uniforms, high public profile, and enviable work environment, NPS rangers developed what Horace M. Albright described as "the ranger mystique." Their search and rescue activities sometimes received a large play in the local press. In 1929, Ranger Charlie Browne was awarded the first citation for heroism ever issued by the Department of the Interior for his leadership in the rescue of three climbers and the recovery of two bodies following a climbing accident on the Gibraltar route of Mount Rainier. [13]

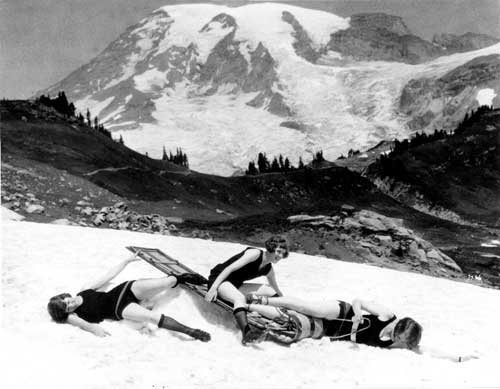

On a lighter note, Albright once commented to Tomlinson on the number of rescues reported out of Mount Rainier that involved young college-age women in distress. Tomlinson replied that despite appearances from the press clippings, his rangers were quick to assist all injured or imperiled park visitors without regard to age or sex. As for the reports that Albright alluded to, he felt that the rangers were "living up to the best traditions of our Service and the time honored chivalrous male attitude of 'hastening to the aid of beauty in distress.' " Tomlinson added, "I am sure that if you could but enjoy the experience of watching a Sunday crowd of beautiful lady skiers at Paradise Valley the gallant attitude of the Mount Rainier rangers would be highly commended." [14] Tomlinson's relationship to his ranger staff was like a good army officer's relationship to his men: respectful, responsible, and authoritarian. To Park Service rank and file, Tomlinson was always "The Major."

|

| Young women engaged in summer snowplay was a common theme used in Rainier National Park Company publicity photos such as this. (O.A. Tomlinson Collection photo courtesy of University of Washington, Negative No. 1574.) |

Engineers

A new aspect of national park administration after 1916 was the periodic visits by various engineers, who reported to the NPS director on specific features of the park's infrastructure and recommended improvements. The most important of these experts were the landscape, road, and sanitation engineers. These individuals were members of the new NPS bureaucracy. Their field offices were located in the West in order to better serve the western national parks.

Mather appointed Charles P. Punchard, Jr. as the Park Service's first landscape engineer in 1918. Punchard made a four-day inspection of Mount Rainier in May 1919, supplying Mather with early recommendations on how to clean up Longmire, improve the appearance of the roadways, and develop the two main administrative sites at Longmire and Nisqually Entrance. [15] Although Punchard was able to devote relatively little time to Mount Rainier before his death in 1920, he was able to lay a foundation for subsequent landscape work in the park. Landscape architecture historian Linda Flint McClelland has described Punchard's influence as vital, for he translated the landscape policy of the NPS into practices that would influence the character and management of all the parks. "Punchard's work," wrote McClelland, "followed the state-of-the-art principles for developing natural areas that had evolved out of the American landscape gardening tradition." [16] Mather gave close attention to Punchard's opinions and recommendations.

After Punchard's death, his assistant, Daniel R. Hull, was promoted to chief landscape engineer. Hull maintained his office in his home city of Los Angeles, serving until 1927, when Mather decided to consolidate all field divisions in a western field office in San Francisco. At that time Hull resigned and was succeeded by his first assistant, Thomas C. Vint. Vint oversaw the expansion of the Park Service's Landscape Division. He hired additional landscape architects and assigned them to different parks. Vint assigned landscape engineer Ernest A. Davidson to work in Mount Rainier, Yellowstone, and Glacier. [17] Davidson had a large influence on landscape design in the park and the development of Longmire and Sunrise in particular. Vint himself played a key role in the development of Mount Rainier's first master plan between 1926 and 1928. [18]

Another important specialist on whom the park superintendent relied for expertise was the NPS chief engineer, George E. Goodwin. Mather met Goodwin in Crater Lake National Park, where he was in charge of road development by the Army Corps of Engineers. With the establishment of the NPS in 1916, Mather hired Goodwin, gave him a field office in Portland, and put him in charge of all national park road building. Goodwin continued in this position until 1925, when he resigned and Mather negotiated with the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads to assume this task. [19]

Although the NPS Engineering Division was relieved of its function of road building, it continued to assist each park with all other improvements. The work included buildings, trails, public campgrounds, and minor road projects. Bert H. Burrell succeeded Goodwin to the post of chief engineer in the summer of 1925. Beginning in 1927, R.D. Waterhouse was assigned to Mount Rainier each summer as acting resident engineer. [20]

Another expert who had a hand in Mount Rainier's administration in this era was Harry B. Hommon, sanitary engineer with the U.S. Public Health Service. Assigned to the national parks, he quickly established a reputation for excellent work. He helped design water and sewer systems, prescribed methods for garbage disposal, and worked with park concessions in improving sanitation standards in hotel and camp kitchens. He visited Mount Rainier twice in the summer of 1921 and made a detailed report on sanitation in Mount Rainier National Park in 1922. [21] Later he assisted with the designing and planning of sewer systems at Yakima Park, Paradise, and Longmire. [22] Hommon continued to serve the national parks for twenty years. [23]

At the end of the 1920s, national park management had become so diversified as to warrant the designation of several administrative departments within each park. Departmentalization was a system-wide initiative. In Mount Rainier National Park, there were now six departments: protection, maintenance, educational, engineering, landscape engineering, and electrical. Heading the departments were the chief ranger, maintenance foreman, park naturalist, resident engineer, resident landscape engineer, and park electrician, respectively. [24]

Improvements in Office and Housing Conditions

Park rangers were generally expected to live in the park in government-subsidized housing. Most of the staff lived in Longmire or at Nisqually Entrance. Both places tended to be dark and damp in the off-season, and the residence requirement could be a hardship, particularly for permanent employees with families. At first, new building construction did not keep pace with increases in park staff. As late as the mid-1920s, some permanent rangers and their families were still living in tent cabins through the winter at Longmire. [25] These miserable housing conditions were not conducive to building up a dedicated ranger staff As the situation was slowly rectified during the 1920s, Longmire grew from a few government buildings into a small employee village. To the existing ranger residence, ranger station, warehouse, community kitchen (the present-day library), and first park administration building, were added four small residences in 1923, another residence in 1926, and three more residences together with a large community building, the latter located on the other side of the Nisqually River, in 1927. The following year, the NPS completed a handsome new administration building in the rustic style using plans provided by the Park Service's new Western Branch of Landscape Design in San Francisco. Tomlinson enthused that this building was "one of the finest ever constructed with National Park funds." [26] Together with the landscaped grounds, rock-lined plaza, and numerous plant beds, all laid out under the direction of landscape engineer Ernest A. Davidson, the new administration building gave the Longmire complex an air of spit-and-polish government efficiency.

Longmire became a more livable place in one other important respect. Beginning in the winter of 1925-26, the NPS made arrangements with the Rainier National Park Company to open a school at Longmire, setting up desks, blackboards, and other schoolroom furnishings in the National Park Inn during the off-season. The NPS paid half of the teacher's salary and parents paid the other half, and the teacher was employed through the Pierce County school superintendent. In the first year there were fourteen children in the Longmire vicinity who attended the Longmire school. [27]

As the untidy, unsanitary, and somewhat commercialized appearance of Longmire gave way to a neat, orderly, official-looking place in the 1920s, it was easier for the resident rangers and their families to feel a sense of esprit de corps or professional pride. The development of the government village at Longmire signified the park administration's transformation into a professional organization.

Telephone Communications

All electronic communications between park staff in this era were conducted by telephone; radio did not come into use until the 1930s. The earliest telephone service in the park was built under special use permit by the Tacoma Eastern Railroad Company in 1911. In 1913, the Department of the Interior allotted $750 for construction of a government line between the Nisqually entrance and Paradise Valley. [28] For this project the government adopted the single-wire grounded system used by the Forest Service: the line was suspended from tree to tree (loosely, so that it would give up slack when struck by a windthrow) with the ground completing the circuit. Over the years, the government telephone system was extended to all ranger stations in the park. Soon it encircled the mountain. By 1920, it was possible to make calls from the park to any city on the West Coast. [29]

In October 1918, the Tacoma Eastern Railroad Company sold its telephone line to the NPS. The park administration then operated not only the telephone system in the park but the line from the park entrance to National (one mile west of Ashford). As a courtesy, the NPS allowed the park concession and local residents to use this government line free of charge. The system was soon overburdened. As many as 6,000 calls would be made each summer, all of them handled through a switchboard in the superintendent's office. In 1920, the NPS persuaded the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Company of San Francisco to take over the telephone exchange at National, but it could not induce the company to purchase the line beyond that point to the park entrance. The reason was that local residents west of Ashford challenged the right-of-way for the telephone line, claiming that they had only agreed to a right-of-way for the road. As a result, the NPS had to continue to operate the line outside of the park as far as National. It charged the concession and local users a toll, and two telephone operators were added to the park staff each summer beginning in 1922. [30]

By the end of the 1920s, the park's telephone system was showing its age. Superintendent Tomlinson described the system in his annual report for 1929:

Two metallic and one ground circuit to Paradise Valley and the commercial circuit outside the park were maintained in addition to the 125 miles of single grounded wire encircling the mountain and connecting all of the ranger stations with the telephone switchboard at Longmire. Due to the poor type of construction, considerable difficulty was experienced in maintaining the telephone service sufficient to take care of the greatly increased business between Paradise Valley and the commercial lines. During the fire season it was necessary to send a special lineman and a small crew entirely around the park to repair and improve the grounded circuit which had become in such a bad condition that the service was unreliable.

All wires have been strung on trees and during severe winter conditions frequent interruptions of service are caused by the falling and swaying. Many breaks have also necessitated constant splicing and repairing, making it necessary to replace a great deal of wire. [31]

These troublesome conditions set the stage for the park's early experimentation with radio (see Chapter XII).

INTERPRETATION

The idea that national parks were places of outdoor learning as well as recreation had roots in the nineteenth century, but the creation of the National Park Service in 1916 gave the idea new impetus. [32] One of the chief distinctions between national parks and national forests, Mather emphasized, was the significance of the former as "national museums of native America." [33] The idea quickly took hold that one of the essential functions of the NPS would be to enhance the educational value of national parks through the dispensing of informative pamphlets, the offering of guided nature walks, the development of museum collections, and other appropriate means. These varied activities eventually came under the term "interpretation." The NPS would interpret the park's natural and cultural features for the public.

Publications

A serious deficiency of national parks during the years they were administered directly by the Secretary of the Interior was the dearth of published information available to the park visitor. Many national park areas were featured in scientific studies, particularly in USGS bulletins and professional papers, but these writings were generally too obscure and technical to be of much use to the general public. As the department's chief of publications, Laurence F. Schmeckebier pointed out in 1912, there was an urgent need for a series of short pamphlets that would provide the traveler with basic information on transportation, accommodations, and points of interest in each park. Beyond that, wrote Schmeckebier, a national parks bureau should be established with a view to promoting the educational value of national parks. One of the bureau's chief functions would be "to arrange a series of publications that will deal clearly and in general terms with the geology, the botany and the zoology of these great reservations that are being administered by the government for the benefit of the people." [34]

The fledgling NPS produced two informative books on the national parks in 1916: Glimpses of our National Parks and National Parks Portfolio. The latter was an elegant picture-book that the department put together with financial assistance from the railroads. These works were followed by pamphlets on specific parks: Geologic Story of the Rocky Mountain National Park by Willis T. Lee; The Volcanic History of Lassen Peak by J.S. Diller; and Wild Animals of Glacier National Park by Vernon Bailey, among others. [35] Three government pamphlets appeared in quick succession on Mount Rainier National Park: F.E. Matthes, Mount Rainier and its Glaciers (1914), John B. Flett, Features of the Flora of Mount Rainier National Park (1916), and Grenville F. Allen, Forests of Mount Rainier National Park (1916). Meanwhile, Professor Edmund S. Meany produced an anthology of writings covering the human history of Mount Rainier, titled Mt. Rainier: A Record of Exploration (1916). The idea that was basic to these semi-popular tracts was that tourists would derive more pleasure and benefit from their visit if they knew "the story behind the scenery."

The need for a guide book to Mount Rainier's wildlife led to a cooperative agreement between the NPS, the Bureau of the Biological Survey, and the State College of Washington (now Washington State University) in 1919. Dr. W.P. Taylor of the Biological Survey and Professor W.T. Shaw of the State College of Washington collaborated on a faunal survey with the assistance of park ranger and botanist John B. Flett and Oregon state biologist and photographer William Finley. The plan was that the NPS would publish the book in a popular format, similar to the book on Glacier's wildlife written by Vernon Bailey. [36] However, the book did not come out until 1927.

Thus, the park did not have a good, popular work on natural history until the appearance of Our Greatest Mountain by Floyd W. Schmoe in 1925. [37] This 366-page handbook ably served the purpose. It not only provided descriptive material on all roads and trails in the park, but contained chapters on human history, geology, fauna and flora. Schmoe was park naturalist when he wrote the book. Although it was published by a private publishing house, it was a semi-official publication. Schmoe drew upon park records for much of his material, and Superintendent Tomlinson gave Schmoe some duty time in which to write it. [38]

Another type of national park publication initiated during the 1920s was the regular publication of "nature notes." Schmoe began producing Mount Rainier Nature Notes in 1924. It was one of the earliest such publications in the NPS, and followed the example set by Yosemite Nature Notes, which began in 1922. Yellowstone National Park began to publish nature notes in 1924, Grand Canyon in 1926, and Zion, Crater Lake, and Rocky Mountain in 1928. [39] Mount Rainier Nature Notes continued to come out in mimeographed form each month for more than a decade.

Nature Guide Service

The concept of assigning park rangers to interpretation evolved fairly quickly after the creation of the NPS in 1916. As in other national parks in this period, the Mount Rainier park administration worked in close collaboration with the park concession to create a nature guide service. By the mid-1920s, the NPS and the Rainier National Park Company worked out separate and compatible functions: the company handled the mountain guide service, while the park's educational department conducted nature walks. The NPS officials who led these walks wore the regular park ranger uniform but were called park naturalists to distinguish them from the ranger force.

The collaboration between the park administration and the Rainier National Park Company was not immediate. In 1916, Superintendent Reaburn reported the establishment of an "information bureau" at Longmire—an entirely unilateral development. Ranger John B. Flett, a Tacoma high school biology teacher who had been working at Mount Rainier each summer since 1913, was assigned the task of informing tourists about points of interest, assigning them places to camp, and answering their questions. "Prof. Flett's intimate knowledge of the flora, trees, and points of scenic interest in the park was a source of much interest," Reaburn wrote. "This information was sought by large numbers of visitors." [40]

The Rainier National Park Company, for its part' hired the longtime Mount Rainier National Park booster, Asahel Curtis, to supervise the handful of mountain guides who now entered the employ of the single park concession, to manage sales of photographs and souvenirs, and to give campfire talks at Paradise. The company employed Curtis from June 15 to September 15, 1917, for a monthly compensation of $250. [41] The following year, the company expanded the guide service to include "flower walks" and guided tours onto the Paradise and Nisqually glaciers. Otis B. Sperlin, a Tacoma high school teacher, replaced Curtis as head of the guide service. Alma Wagen, Mount Rainier's first woman summit guide, was hired that year. The company's popular guide service drew accolades from Mather in his annual report for 1918:

Trail trips were under the efficient guidance of trained mountaineers, one or two of whom were women. Illustrated lectures on the park, its glacial system, its wild flowers, and trails were given regularly by the chief of the guide service, an able and enthusiastic high school professor possessing a deeply rooted devotion to the mountain. Guides, principally women, were also employed to conduct studies of the wild flowers and other plant life while making short walking trips from the hotel and camps in Paradise Valley. [42]

Mather predicted that the demand for "these outdoor teachers" would grow rapidly. The guide service in Mount Rainier was modelled on that developed the year before in Rocky Mountain National Park, where the NPS exercised some control through a system of examinations and licensing. [43]

The park administration inaugurated its own nature guide service in 1921. On the recommendation of Professor Edmund S. Meany, Superintendent Peters hired Charles Landes, a high school biology teacher from Seattle, as a seasonal park ranger and nature guide. Landes was assigned to Paradise, where he led visitors on nature walks and gave nightly lectures illustrated with lantern slides. Landes also prepared a collection of cut flowers and plants numbering about 100 species for display. [44] Landes was rehired the following summer, and Acting Superintendent Nelson reported at the end of the season that the nature guide service had been continued "in the way of an experiment" and was proving very popular. The evening lectures, which were moved to the new Guide House, were attended by capacity crowds. [45] Rehired again in 1923, Landes set up a naturalist's office at Paradise with exhibits on flora, fauna, and geology and gave talks to an estimated 15,000 visitors in the course of the summer. It was clear that popular demand exceeded what the small interpretive program could deliver, and Superintendent Tomlinson recommended the creation of a permanent park naturalist position the next year. [46]

The following summer, the interpretive program was expanded to include one other "naturalist" in addition to Landes. Floyd W. Schmoe, a graduate of the Syracuse University School of Forestry and former guide to the Rainier National Park Company, was assigned to this work. A similar educational service to what was provided at Paradise was inaugurated at Longmire, with lectures given in the "Sylvan Theater" in the public campground and guided walks conducted on the trails out of the area. In the fall, Landes returned to his teaching responsibilities in Seattle, and Schmoe was appointed the first permanent park naturalist of Mount Rainier National Park. In his annual report for 1924, Tomlinson stated that the nature guide service had become "one of the most appreciated features of the park." [47]

Schmoe had three assistants beginning in 1925. The four naturalists worked in pairs at Longmire and Paradise. During the next two years, the interpretive program came to encompass guided walks and campfire programs at White River, new self-guided nature trails at Longmire and Paradise, and regular measurements of the recession of the Emmons Glacier. Schmoe resigned at the end of the 1928 season. C. Frank Brockman was appointed park naturalist that November, and continued in that position until March 1941.

While the park administration's interpretive program took shape in the 1920s, the concession s guide service evolved in a different direction. Two Swiss alpinists joined the guide service in 1919 and stayed with it for several years. The company constructed a Guide House at Paradise in 1922, which doubled as a visitor auditorium and an employee dormitory. It is not clear whether the guide service continued to conduct so-called flower walks, but it is certain that it was increasingly oriented to glacier tours and summit climbs. The professionalism of the mountain guides drew consistent praise from the superintendent. While this splitting of visitor services developed to everyone's satisfaction, the commercial guides and the park rangers still collaborated on occasional mountain rescues.

The Longmire Museum

A basic function of the park naturalist in these years was to collect and inventory biological specimens. Ranger John B. Flett made the first official botanical collection in the park, and assisted in 1919 with an official faunal survey by the Biological Survey. Naturalist Charles Landes made an extensive collection of flowers. Park Naturalist Schmoe was given a cougar that had been killed in the park so that it could be stuffed and mounted. (This old specimen may still be seen in the museum at Longmire.) [48] As these things accumulated, the need grew for a suitable museum building in which to display them to the public. In 1925, small exhibits were set up in the new stone ranger station at Paradise and in the superintendent's house at Longmire. These were temporary arrangements. In 1927, NPS Chief Naturalist Ansel F. Hall assisted Schmoe in planning and preparing exhibits for an eventual park museum. [49]

With the completion of the new administration building in 1928, the old administration building was vacated and converted into the first museum in Mount Rainier National Park. (The museum is still in use and contains some components of the original displays.) [50] The following year, the museum display at Paradise was moved into the new community building. In 1931, the first of two ranger's blockhouses to be located in front of the administrative building at Sunrise was completed, and this became the naturalist's headquarters. That same year, the Longmire Museum was refurbished with modern lighting and new historical and anthropological exhibits were developed with the assistance of the Washington State Museum in Seattle. [51]

NATURAL RESOURCE PROTECTION

The advent of the Park Service brought qualitative changes to natural resource protection in Mount Rainier National Park. Few natural resource policies were changed in the Park Service's early years, but natural resources were protected with greater fervor than they had been before. This was not surprising, for the protection of natural resources lay at the heart of the National Park Service mission. That mission was "to faithfully preserve the national parks for posterity essentially in their natural state." [52] No other agency in the Department of the Interior had such a succinct and focused mandate as that which Congress provided for the NPS in the organic act of 1916. The agency's crisp mandate was a decided advantage in the formation of a professional organization. Superintendents, rangers, and engineers could be inculcated with a shared sense of mission. The agency could become the recognized authority in specialized fields such as preservation, interpretation, and landscape architecture. The one professional goal that all administrative divisions of the NPS had in common was the protection of natural resources. [53]

Park administrators dealt with a somewhat narrower range of natural resource issues in this era than they had during the park's founding years. There were no prospectors in the park, only a few persistent mining claimants. There were no more timber sales. The threat to wildlife from poachers diminished. The threat from grazing interests resurfaced briefly during the First World War and then subsided. By and large there was little innovation in natural resource protection, only a deepening of commitment. The one decisive change in natural resource policy in this era was in the treatment of predators, and that came at the end of the 1920s.

Grazing

The national call to arms in the spring of 1917 led many westerners to demand the throwing open of public reservations ostensibly for the war effort but really for short-term economic gain. One of the most brazen requests was to allow the shooting of Yellowstone elk and buffalo in order to increase the nation's food supply. While the head of the U.S. Food Administration, Herbert Hoover, promptly slapped down that proposal, demands to open the national parks to sheep grazing in order to increase the meat supply were a good deal more persistent. As Mather phrased it rather dramatically in 1918, "this danger, like the sword of Damocles, hung over both the scenic features and wild life of the parks." [54]

Much to their chagrin, preservationists were forced to accept a provision for grazing in the National Park Service Act of 1916. Grazing was permitted in national parks where such use would not interfere with the primary purpose for which the park was created. For many years preservationists had drawn a sharp distinction between cattle and sheep grazing, for the latter was much more destructive to the vegetation, and this distinction was carried into the NPS regulations following passage of the organic act. Sheepmen saw an opportunity in 1917 to reverse that decision and gain equal access with the cattlemen to national parks. Though there was no coordinated campaign, state wool-grower associations in Washington, Oregon, California, and Montana demanded much the same thing at this time. [55] Demands for entry into Mount Rainier National Park were of more than local significance and drew the close attention of Assistant Director Albright. [56]

In October 1917, Washington state's commissioner of agriculture E.F. Benson requested that the NPS allow stockmen to pasture 30,000 to 50,000 sheep in Mount Rainier National Park. Benson was himself engaged in sheep raising with Howard Nye of Yakima, and incredibly, he saw no conflict of interest in making this "official" request. [57] Albright replied to Benson in no uncertain terms. The NPS did not allow sheep grazing under any circumstances because: 1) sheep would utterly destroy wildflowers, 2) sheep were obnoxious to tourists, 3) sheep would frighten the wild animals, which were otherwise becoming tame and relatively easy for tourists to observe, and 4) sheep would destroy trails and greatly increase the cost of maintaining and protecting the park. The policy applied to all national parks, but was all the more applicable to Mount Rainier National Park, which was renowned for its beautiful wildflower displays in the high meadows where sheep would be most apt to pasture. [58]

Dissatisfied with this reply, Benson went to the press to try to rally public opinion. He ridiculed Albright's letter, and volunteered to pay a higher premium for grazing privileges for his own sheep, if the Department of the Interior required it, "in order to stimulate wool and mutton production to meet war necessities." One sympathetic Seattle newspaper reproduced the correspondence between Benson and Albright and headlined the story, "Sheep Scare Bears, Eat Pretty Flowers." [59] The Mountaineers, meanwhile, came to the Park Service's defense, advertising that the club members would pasture sheep on their own lawns for the war effort before they would condone opening the national park to sheepmen. [60]

Benson secured Governor Lister's support. The governor wrote to Hoover of the Food Administration. Albright immediately went to work on Hoover, and on January 9, 1918, finally received the unequivocal statement he was looking for: "The U.S. Food Administration concurs with the Department of the Interior that the Government's policy should be to decline absolutely all such requests." [61] Albright and Mather were thrilled by this response; it effectively ended the sharp struggle to open the park to sheep grazing.

Cattle grazing continued to be a menace to the park's resources, though it was regarded as less serious than the threat from sheep grazing. In March 1917, Superintendent Reaburn received a standardized questionnaire on the feasibility of grazing cattle and horses in Mount Rainier National Park for the duration of the war. Reaburn took this official questionnaire as a cue to inform livestock interests in the state that the park administration would likely confer grazing permits that summer. For this indiscretion he received a reprimand from Mather, who insisted that action on grazing applications would only be taken in Washington, D.C. [62]

By then, however, Reaburn had already granted a permit to R.T. Siler and J.E. Batson of Morton, Washington, to graze 200 head of cattle on the Cowlitz Divide during the summer of 1917. Late snows did not allow Siler and Batson to utilize their permit that year; nevertheless they applied for a permit the following year to graze 200 to 500 head in the park. Mather decided to grant this privilege. [63] A few months later, Mather authorized another permit for Henry J. Snively, Jr., this one for 500 head to graze in Yakima Park. Both areas were grazed during the summer of 1918. Snively's permit was reissued in 1919 and 1920, after which Mather informed the cattle owner that the war emergency had passed and the privilege was therefore being withdrawn. [64]

The limited amount of cattle grazing that was permitted on the east side of the park in 1918-20 caused visible damage to the vegetation as well as soil erosion. It is quite possible that the grazing permits would have been renewed indefinitely under the prior administration by the Secretary of the Interior. It is probably fair to say that the termination of these grazing privileges (and the prevention of sheep grazing) indicated a more protective stance on the part of park officials, which owed something to the new environmental ethos being fashioned within the Park Service.

Mining

Park officials had to contend with the possibility that significant mining operations could begin at any time on any of the existing mining claims in the park. Such mining operations could, of course, have serious repercussions for the park's natural resources. As it turned out, the only mining activity in the park in this era consisted of the small amount of yearly assessment work that was required to maintain the various valid mining claims. In two cases—the Hephizibah group of mining claims and the Lorraine group of mining claims—General Land Office agents detected that the assessment work was not being done and adverse proceedings were undertaken against the claimants. By these means two potential mining operations were eliminated from the park in 1923 and 1927 respectively. [65]

In the case of the Mount Rainier Mining Company operation in Glacier Basin, a General Land Office investigation of the company's forty-one claims may have prompted the company's officers to consolidate their claims. In 1924, a year after the investigation, eight of the claims went to patent and all the others were relinquished. On balance, this was not good news for the park administration. Now the eight claims were alienated—constituting another private inholding in the park. Like the Longmire property, they would have to be acquired through purchase or donation.

The story of the Mount Rainier Mining Company took a strange twist in this era, and as it turned out, the NPS missed a favorable opportunity to eliminate this inholding. In 1928, the company's stockholders filed a complaint against the company president, Peter Storbo, for misrepresenting the value of the company's stock. Storbo and his associate, Orton E. Goodwin, were charged with use of the mail service to defraud the stockholders. Two years later they were convicted, fined $1,000 each, and sentenced to eighteen months in the federal penitentiary. [66] The patented claims were sold at a sheriffs auction in 1932, in the depths of the Great Depression, for a mere $500. The high bid was made by one Thomas E. Engelhorn of Churches Ferry, North Dakota. Apparently no effort was made by the NPS to acquire the claims at this time. After the Depression (and after Engelhorn was dead) the Mount Rainier Mining Company would rise again, reconstitute a threat to the park's natural resources, and detract from the park's integrity until the claims were finally acquired by the government in 1984. [67]

Forests

The attitudes of park administrators toward the forest resources in this era might be described as transitional. The habit of judging the forest's aesthetic value in terms of its market value, which so dominated the thinking of the park's early superintendents, receded in the 1920s. No cutting was permitted except in connection with road and building construction and for the clearing of scenic vistas at key points along the roadway. But park superintendents still viewed the forest as so many trees to be protected, rather than as a living community. Fires, forest diseases, and insect infestations were regarded as purely destructive, an unmitigated blight, rather than natural events in the life of the forest. It was NPS policy to fight all three of these scourges to the fullest extent that funds would allow. Funds for forest protection remained relatively modest, however, until the end of this period.

Park officials regarded wildfire as the biggest threat to the forest. Although wildfire was much less prevalent around Mount Rainier than east of the Cascade Divide, owing to the area's high precipitation, park officials were still mindful of the potential for runaway fires. Evidence could still be seen of forest fires that predated "the advent of the white man" in the area. Silver snags from an old burn on the Muddy Fork of the Cowlitz, for example, covered approximately twenty square miles within the park. Numerous old burns in the higher elevation forests were attributed to the Indians, who had deliberately set fires in order to encourage the spread of huckleberry patches and to make hunting easier. Even some of the slow-growing subalpine stands in the upper mountain hemlock zone showed evidence of fire damage which had been caused by careless campers around the turn of the century. [68]

If Indians no longer set fires in the park, there were numerous other causes of fire that park officials now had to contend with, and the general perception was that in the absence of a system of forest protection the fire danger would mount over time. The sheer numbers of park visitors were a prime threat. "Increased travel unfortunately brings increased fire hazard due to a certain percentage of visitors who are careless in the disposal of burning matches and tobacco or who fail to extinguish their campfires," observed the NPS's fire control expert, John D. Coffman. The extensive road clearing and slash disposal occurring in this era also entailed added risk of fire. The increasing amount of logging taking place outside the park posed a threat, as fires which started in the national forest could burn into the national park. For all of these reasons, the policy was to fight all fires, regardless of origin. Even lightning-caused fires were to be put out as quickly as possible. [69]

With the growth of the ranger staff, the park administration was able to put more men on forest patrol each season, and to bolster those numbers during periods of extreme fire hazard or after a lightning storm. Indeed, superintendents often cited the need for more firefighting capability in order to obtain additional ranger positions for the next year. (This request played well in the House and Senate appropriations committees—better to ask for more firefighters than for more traffic controllers or nature guides.) Over the years, the park administration was also able to scrounge together a large cache of fire suppression tools, Evinrude pumps, several thousand feet of fire hose, and scores of bed rolls for firefighters. This equipment was cached at Longmire, the Nisqually entrance, and the district ranger stations at Carbon River, White River, and Ohanapecosh. [70]

For the first quarter century of its existence, Mount Rainier National Park experienced no large forest fires. In the summer of 1914 there were seventy-five consecutive days without rain, and forest fires were so prevalent outside the park that the heavy pall of smoke discouraged people from visiting the park during August. But no significant fires occurred within the park. After another dry summer in 1925, Mount Rainier experienced a run of serious fire years. On June 9, 1926, the National Park Inn was destroyed by fire. Though the building was lost, park personnel prevented the fire from spreading to the neighboring forest. In August 1927, thirteen lightning-caused fires and two human-caused fires burned an estimated 334 acres of park lands. The worst fire of 1928 started from the road-clearing operation on the west side and burned about 200 acres on Klapatche Ridge. [71] During the 1929 fire season, park rangers suppressed twenty-five fires: twenty-one within the park, two that began outside the park and spread into it, and two that threatened the park but were controlled entirely outside. Sixteen of the fires were lightning caused and nine were human-caused. [72] One of the more sizable fires was started by the Westside Road construction crew and burned another forty acres of forest on Klapatche Ridge. [73] In October 1930, road-clearing operations on the Westside Road sparked yet another fire which crowned more than 8,000 acres in the Sunset Park area and killed about 3,000 acres of forest. [74]

Expenditures for fire suppression in Mount Rainier National Park grew dramatically from less than $200 in 1925 to more than $18,000 in 1930. [75] In the course of several serious fire seasons, the park obtained valuable training and equipment. Park rangers attended a USFS fire school at Cispus, in the Rainier National Forest, in 1929. They received a three-day course in fire control from the NPS's fire control expert, John D. Coffman, in 1930 and again in 1931. [76] Coffman also prepared a report on forest protection requirements in Mount Rainier National Park. Coffman's report marked a watershed in the park's forest protection policy, as the NPS moved toward a system of fire lookouts in Mount Rainier National Park in the early 1930s.

Up to 1930, Coffman wrote, the park had depended almost entirely on the Forest Service for its lookout service. (Park rangers would sometimes occupy observation points after an electrical storm, but that was the extent of the park's own lookout system.) There was but one permanent lookout station within the park—at Anvil Rock, 9,584 feet high on Mount Rainier's southern flank—and this had been established by the Forest Service back in 1917, and manned by the Forest Service each summer under a cooperative agreement with the NPS. The park received the benefit not only of this lookout but several other lookouts in the surrounding Rainier National Forest. "It is only fair that the park should bear its share of this lookout service," Coffman advised. Thus, he opined, the NPS should take over the Anvil Rock Lookout and construct two or three additional fire lookouts on and around Mount Rainier. [77] The development of this lookout system is discussed in Chapter XII.

The serious fire seasons of 1926-1930 generated interest in other forest protection problems in Mount Rainier National Park, namely forest-tree disease and insect control. In October 1928, NPS Assistant Forester C.C. Strong surveyed the park's white pine with P.S. Simcoe of the Office of Blister Rust Control, Bureau of Plant Industry, Department of Agriculture. White pine trees were not abundant in Mount Rainier National Park, but in some areas of the park they were of "inestimable scenic value." The survey found that white-pine blister rust was a serious menace to these scattered stands of white pine. [78]

White-pine blister rust is an introduced, canker-forming, forest-tree disease caused by the parasitic fungus Cronartium ribicola. The organism has two dependent phases, one on the white pine trees and the other on currant or gooseberry bushes of the genus Ribes. The disease is communicable from the trees to the ribes bushes for up to 150 miles, but from ribes bushes to tree the windborn spores travel at most about 900 feet. It was found that the forest blight could be fought effectively by eradicating the ribes bushes in the white pine stand and in a limited zone around it.

The disease was introduced from across the Atlantic in 1909, first appearing in white pine in New York. It was introduced on the West Coast one year later, at Vancouver, B.C., on a shipment of white pine seedlings imported from France. The disease spread inland from both coasts during the next forty years. It spread fairly quickly in the Pacific Northwest because of the abundance of ribes bushes. In the mid-1920s, the U.S. Forest Service and timber-owning companies decided against making any effort to control this disease in the relatively minor stands of white pine in western Washington, where Douglas fir predominated. Their decision was based on economics rather than aesthetics. The investigation of blister rust in Mount Rainier National Park by Strong and Simcoe came a few years afterwards, and demonstrated an interesting divergence of forest policy between the national park and the surrounding public and private timberlands. [79]

Mount Rainier National Park received an initial allotment of $5,200 for blister rust control in 1930. Work commenced in mid-June on the clearing of wild currant and gooseberry bushes in the Longmire area and in the Silver Forest (on the road to Narada Falls). At the same time, a more intensive survey was initiated to identify other stands of white pine in the park that might also be protected. [80] This was the beginning of an effort that would continue for more than twenty years, much of it being accomplished by the Civilian Conservation Corps during the 1930s.

The inauguration of blister rust control in the park brought with it the first significant effort at insect control. Numerous red-topped white pines were found to be infested by the white pine beetle (Dendroctonus monticola), and as Coffman pointed out, it would be incongruous to undertake blister rust control if the white pine were still allowed to succumb to a beetle infestation. [81] An entomologist from the Bureau of Entomology made an examination of insect-damaged white pines near Longmire in the fall of 1929 and recommended an allotment of $500 to treat these trees. About 300 trees were either burned or peeled in the Longmire and Ohanapecosh areas in 1930. [82]

Fish Stocking

NPS officials regarded Mount Rainier National Park's lakes and streams as recreational resources. The lakes would naturally attract boaters, swimmers, and fishermen; the streams, when they ran clear and did not contain glacial flour, would make attractive fishing places. To preserve these bodies of water in a natural state was to protect the public's access to them, keep their shores and banks in a pristine condition, and prevent their spoliation by water development schemes or the dumping of pollutants. It was not part of the preservationist creed at this time to consider lakes and streams as distinct biological communities. Stocking these waters with fish, even if the fish did not occur in them naturally, was thought to be a good thing. [83]

Park officials did not stock the lakes themselves, but they welcomed fish plants by state and county fish wardens. The first such fish plant was made in September 1915 in the northwest corner of the park by Pierce County Fish Warden Ira D. Light. The warden planted 25,000 eastern brook trout fingerlings, and the park administration put a four year closure of the waters in effect. At the end of the period, the fish in Mowich Lake were eighteen inches in length. This was followed by a second plant, in 1917, of 25,000 fingerlings by Pierce County wardens, apportioned between Louise Lake, Reflection Lakes, Golden Lakes, Lake George, and Fish Creek. These areas were likewise closed to fishing for four years. In the summer of 1920, an additional 10,000 fingerlings were planted in Louise Lake and Reflection Lakes, both of which would soon become the most popular and heavily fished lakes in the park. [84]

By 1923, Mount Rainier National Park was acquiring a local reputation for good sport fishing. At Lake George, it was reported that nearly everyone who dipped their line in the water was catching the limit of ten fish per day. The State of Washington Fish and Game Commission now joined the Pierce County Game Commission in providing fish fry from nearby hatcheries—and in larger numbers. Under a cooperative agreement with the NPS, the state and county game commissioners deputized four park rangers as fish wardens, who then assisted state and county wardens with fish plants in their respective districts: 60,000 in Mowich Lake and Golden Lakes, 30,000 in the White River district, 52,000 in the Ohanapecosh district, and 15,000 in the vicinity of Longmire. [85] Additional plants of 180,000 to 200,000 fingerlings were accomplished in 1924 and 1925, and trout fishing was reported to be excellent in Lake George, Louise Lake, and Reflection Lakes. [86]

If these fish plants were large by earlier standards, however, they were still nowhere near what the park required, in Superintendent Tomlinson s view. [87] With Mather's backing, Tomlinson applied to the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries for 500,000 Montana black spotted trout (cutthroat) fry in the spring of 1928. The somewhat cumbersome procedure was to obtain eggs from Yellowstone National Park, have them shipped to hatcheries in Pierce County, and then have the fry delivered to the park by the Pierce County Game Commission. [88] As a result of this effort, 274,500 rainbow, eastern brook, and Montana black-spotted trout were planted in park streams in the fall of 1928. [89]

Due to the rising demand for fish fry in national parks, the Bureau of Fisheries and the NPS made a cooperative agreement in 1929. The bureau's Commissioner Henry O'Malley visited Mount Rainier that summer and authorized his local representative, J.R. Russell, to work with park officials in fully stocking Mount Rainier National Park's lakes and streams. It was thought that the most expeditious way to accomplish this would be to develop a fish hatchery inside the park. Russell inspected several possible sites with fish culturalist Joe Kemmerich, who was superintendent of the Birdsview Hatchery, and Landscape Engineer Ernest A. Davidson. A site on Fish Creek, in the southwest corner of the park, was given close consideration; Davidson requested that preliminary plans be submitted for action by the Landscape Division. [90] After further negotiations between the NPS and the Bureau of Fisheries, the latter built a new fish hatchery at Silver Springs, just outside the northeast corner of the park. Tomlinson expressed hope that with the help of this hatchery, they would be able to "bring the number of fish in the park up to the point where anglers will be anxious to come to the park for the fishing." [91]

With the assistance of the Bureau of Fisheries, there was a marked increase in the number of fish planted during the early 1930s: 290,000 in 1930, 320,000 in 1931, 450,000 in 1932, 511,000 in 1933. Moreover, new areas were stocked, including Lake Eleanor, Green Lake, Ghost Lake, and several creeks. After four years of cooperative effort, Tomlinson felt confident that the fish plants would produce much better fishing in the park within a few years. [92]

Wildlife

The 1920s was a time of transition in national park wildlife policy. A growing number of scientists and conservationists urged the Park Service to establish a distinct wildlife policy for national parks. That policy would aim to preserve natural assemblages of wildlife rather than stock the national parks like zoos. As early as 1916, Joseph Grinnell and Tracy Storer of the University of California Museum of Vertebrate Zoology wrote that national parks should serve as examples of the North American environment as it existed before the advent of Europeans. The main thrust of Grinnell's and Stacy's argument concerned the need to preserve the natural balance between predators and prey. They posited that the best way to restore a natural balance was to let nature take its course, terminate predator control programs, and allow the relationship of predator and prey populations to regulate itself. NPS officials were receptive to this idea, as evidenced in the yearly superintendents' conferences during the 1920s. The idea of natural regulation challenged and eventually overturned the common public perception that all predatory animals were "varmints." In 1931, Director Albright declared unequivocally that "predatory animals have a real place in nature, and all animal life should be kept inviolate within the parks." [93]

|

| Visitors in a company stage give a bear a handout. The NPS did not discourage this behavior until the 1930s. (O.A. Tomlinson Collection photo courtesy of University of Washington, Negative No. UW1573.) |

At the beginning of this period predator control in Mount Rainier National Park was primarily a ranger activity during the winter season. Monthly reports by the superintendent record occasional kills; for example, Superintendent Peters made this entry for February 1921:

Ranger Tice bagged a large female cougar and three wild cats during the month, the cougar being killed quite close to the Carbon River Ranger Station.

Some cougar signs have been observed near Narada Falls and it is hoped that Park rangers will succeed in catching one or more of the large cats near that point. [94]

In the fall of 1920, Stanley G. Jewitt of the U.S. Biological Survey made an investigation of predatory animal conditions in Mount Rainier National Park, found evidence of cougar and coyote on the south side of the park, and recommended that the NPS and the U.S. Biological Survey share the cost of employing a professional hunter in the park during the winter. Superintendent Toll initially balked at this arrangement, but apparently it was implemented in some form during the next four winters. [95]

The NPS began to scale back predatory control activity in the national parks as early as 1924. That fall Mather and Cammerer discussed the need for predator control in Mount Rainier specifically. They requested Superintendent Tomlinson's view on whether predator control should be discontinued altogether or left entirely to park rangers under the direction of the superintendent. Tomlinson apparently favored the latter course. In his annual report for 1926, Tomlinson stated that fewer predatory animals were reported than for several years, "indicating that the control work which has been carried on in cooperation with the Biological Survey is bearing results." [96] In 1929 Tomlinson reported that cougar were scarce while bobcat and lynx were "holding their own." [97] It is unclear precisely when NPS officials terminated the predator control program at Mount Rainier, but certainly it received less emphasis as the decade progressed.

TABLE: POPULATION ESTIMATES OF MAJOR ANIMAL SPECIES

| Animal | 1926 | 1929 | Population Trend |

| Deer (Columbia black tail) | 450 | 550 | increasing |

| Goat (white mountain) | 250 | 275 | increasing |

| Bear (black) | 225 | 275 | increasing |

| Wolf (timber) | 10-20 | 10 | decreasing |

| Coyote, bobcat or lynx | 300 | — | — |

| Cougar | 18 | 6-12 | decreasing |

| Eagle | 50 | 20-40 | decreasing |

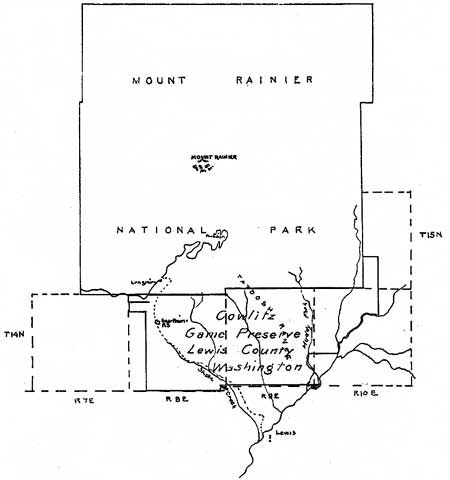

Poaching continued to be a significant concern. In 1920, Superintendent Toll renewed earlier proposals for the establishment of a game reserve bordering the park. Initially, Toll suggested that an area of 457 square miles be set aside as a game reserve. The reserve would completely surround the park and constitute an area nearly half again as large as the national park itself. Nearly all of this would be Northern Pacific or national forest land. After extensive contacts with the Pierce and Lewis County game commissions, Washington Sportsman's Association, Pierce County Sportsman's Association, Washington State Department of Game, and U.S. Forest Service, as well as the two prominent Washington conservationists, Asahel Curtis and Herbert Evison, Toll agreed to a more modest game reserve along the park's southern boundary. [98]

Toll's efforts bore fruit three years later when the Lewis County Game Commission cooperated with Forest Supervisor Grenville F. Allen in establishing this game reserve. The Cowlitz Game Preserve prohibited hunting in an area six miles wide by fifteen miles long, or more or less spanning the Tatoosh Range. Acting Superintendent Clarence L. Nelson commended the game commission for its foresight in giving Mount Rainier's deer population "the best winter range on any of the park borders." With the county's cooperation in protecting the game on its favorite winter range, park officials could now expect the deer population to increase. "More game in the park will, of course, add to the enjoyment of our visitors," Nelson wrote. [99]

|

| The Lewis County Game Commission designated four and a half townships bordering the park as the Cowlitz Game Preserve. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 24-Jul-2000