|

MOUNT RAINIER

Wonderland An Administrative History of Mount Rainier National Park |

|

| PART TWO: FOUNDING YEARS, 1893-1916 |

IV. THE NEW PLEASURING GROUND

INTRODUCTION

The establishment of the nation's fifth national park was a local rather than a national news story. The national park designation added to Mount Rainier's local renown and led more campers and sightseers to seek out its highcountry meadows. Before the park had any regulations in place or a ranger staff to enforce them, local entrepreneurs descended on the park to offer visitors guide services and saddle horses, tent accommodations at Paradise Park and hotel accommodations at Longmire Springs, and a variety of other amenities. Even as the federal government began to establish the rudiments of a park administration and to construct a park road after 1904, it remained a step behind the visiting public and local entrepreneurs. Rising visitor use and public demand for services set the pace for the park's development.

The total number of visitors climbed from 1,786 in 1906 (the first year that the park staff kept an official count) to 7,754 four years later to 15,038 four years after that. In 1915, the first full summer season in which travel to Europe was interrupted by World War I, the number of visitors leaped to 34,814. While these numbers were still small by later standards, it must be born in mind that most public use was concentrated in the southwest quarter of the park and that only one or two rangers were assigned to patrol this area during the same span of years. [1]

Besides the upward trend in numbers of visitors, public use of this new "pleasuring ground" exhibited two other notable characteristics. First, visitors overwhelmingly chose to make Paradise Park either their destination or base of operations. Thus, Paradise Park was established as the center of visitor activity in the national park even before it could be reached by road or adequately patrolled by rangers. Second, public transportation between Puget Sound cities and Mount Rainier National Park evolved rapidly and somewhat chaotically. By 1911, the park's gatekeeper was recording the numbers of people arriving by foot, horseback, wagon, bicycle, stage, and automobile—all of whom shared the same narrow, mountain road to Longmire Springs and beyond. [2]

This chapter considers the changing pattern of visitor use in the new national park and how that influenced the Department of the Interior's administration of the park. The first section of the chapter profiles the park visitors in this era: how they got there, what they did while they were in the park, what kind of problems they posed for management. The second section focuses on the concessioners and the various services they offered. The third section considers efforts by The Mountaineers and the Seattle-Tacoma Rainier National Park Committee to develop the park, both through volunteer labor (in the case of trail construction) and lobbying of Congress (in the case of road construction). The theme of the chapter is that the development of Mount Rainier National Park in this era was largely spontaneous. The Secretary of the Interior provided minimal direction. The basic infrastructure of the park—the road to Paradise, the concentration of visitor services at Longmire and Paradise, the multiple access roads and entrances, the park's orientation to the automobilist and day visitor—developed without benefit of a master plan.

VISITATION: AN EVOLVING PATTERN

Only one road went all the way to the new national park. The so-called Mountain Road was built by James Longmire and a crew of Indian laborers in 1893, and went from Kernahan's Ranch (Ashford) to Longmire Springs. At first use of the road was restricted to wagons whose axles could clear the dozens of stumps that still needed to be rooted out from between the parallel wheel ruts, but by 1896 the road was open to stages. Beginning in that year the Tacoma Carriage and Baggage Transfer Company took tourists to Mount Rainier via an overnight stop in Eatonville. The second popular approach to Mount Rainier at the time of the establishment of the national park was to take the Northern Pacific railroad from Tacoma to Wilkeson, from which the old Bailey Willis Trail led up the Carbon River to Moraine Park. This trail was passable only to foot and horse traffic.

During the first four to five years after the park's creation, upwards of 500 people visited the mountain each summer season. While some visitors were content to remain at the Longmire Springs resort and enjoy the mineral baths and the view of Mount Rainier from there, most wanted to get a closer view of the glaciers and experience the mountain's famous alpine meadows. [3] Paradise Park was the most common destination, but an alternative destination was Indian Henry's Hunting Ground. [4] Both were about six miles by trail from Longmire Springs. On the northwest side, Spray Park and Crater Lake (Mowich Lake) offered popular alternatives to Moraine Park. [5]

Some parties traveled on foot and carried their own bedrolls. The typical visitor, however, came equipped with little more than a few articles of extra clothing in a luggage bag. Most of them hired a packer and saddle horses for the trail, either in Ashford or at Longmire Springs, and rented blankets and a tent when they camped out. Tent space could be rented from a concessioner at Camp of the Clouds in Paradise Park through most of the summer. On the northwest side of the mountain, pack trips had a more expeditionary flavor for there were no tent camps awaiting the traveler in the Carbon River highcountry. [6]

In 1905, the Sierra Club (based in San Francisco) and the Mazamas (based in Portland) organized large expeditions to Mount Rainier. At that time these were the only two well-organized mountain clubs in the western United States. Seattle and Tacoma mountain enthusiasts made several sputtering attempts to form their own mountain club, and finally succeeded with the founding of The Mountaineers Club in 1906. These groups were affiliated and all shared the same basic purpose: to promote outdoor recreation and nature preservation. Each club organized at least one major outing every summer, generally featuring an ascent of one of the Pacific Coast's volcanoes. [7] Although these clubs did not represent the whole gamut of people who were attracted to the national parks, they spoke for a substantial portion of them. The Mountaineers would play an important advisory role in Mount Rainier National Park policy.

Members of these mountain clubs tended to be well-educated, middle-class professionals. The Sierra Club expedition to Mount Rainier in 1905 included a large contingent of college students from Stanford and Berkeley as well as several scientists and professors. The two hundred Mazamas included a dozen or more female college students from Seattle as well as college alumni from twenty-one different American institutions. A common feature of the mountain club outings was to hear campfire talks from the educators in the group, a tradition which prefigured the evening campfire programs provided by the Park Service many years later. During the two weeks that the Sierra Club and Mazamas camped at Paradise Park in 1905, they heard campfire talks by Dr. Charles E. Fay, president of the Appalachian Mountain Club; Joseph N. LeConte of the University of California; Washington State geologist Henry Landes; W.D. Lyman of Whitman College; Dr. Marcus W. Lyon of the Smithsonian; C. Lombardi of Portland, who lectured on his native Swiss Alps; and Samuel Collyer of Tacoma, "who explained the legendary and poetic injustice of naming the mountain Rainier." [8] The mountain clubs, like the Park Service later, believed that nature appreciation needed to be inculcated through cognitive teaching as well as through outdoor recreational experience.

The mountain clubs each had their own rituals and antics, and their simultaneous expeditions to Mount Rainier in 1905 sometimes had the flavor of a cultural exchange. When the large summit party of the Sierra Club passed the four companies of Mazamas on the snowfield between Paradise Park and Camp Muir, they paused to exchange greetings: "Hi, Hi! Sierra, Sierra, Woh!" and "Wah, Hoo, Wah! Wah, Hoo, Wah! Billy goat, Nannie goat, Ma-za-ma!" In Paradise Park itself, the trail between the two camps "saw many a fantastic procession of mountaineers winding its way by moonlight among the giant fir trees" to play some new prank on their fellow mountaineers. At the end of their two-week sojourn the two clubs held a campfire wedding ceremony between a Sierran groom and a Mazama bride, the latter "gowned in white outing flannel, en train, and flowing veil of mosquito netting." [9] The symbolism of the wedding ceremony amounted to something more than a night's amusement. In an era when middle-class professionals were rapidly organizing themselves into national professional associations to consolidate their position in American society, it was not surprising that these middle-class preservationists saw a need to form a national network of mountain clubs to further their goals. The mountain clubs were the forerunners of national organizations like the National Audubon Society and National Wildlife Foundation.

The pattern of use that soon established itself in Mount Rainier National Park—the stage service to Longmire Springs, the hiring of outfitters, the use of highcountry tent camps, the popularity of Paradise Park, the occasional large-group outings like those in 1905—was not, as some members of Congress had hoped, going to be self-regulating. A variety of inquiries, complaints, recommendations, and applications for permits dribbled into the office of the Secretary of the Interior after 1899. There was, for example, the problem of issuing permits to legitimate guides and outfitters who would not defraud the tourists or lead them into danger. It might have seemed to Secretary of the Interior Ethan A. Hitchcock as if every local settler who had ever led a party up to Paradise Park was now claiming to be an oldtimer in the business. Each one wanted to secure an outfitter's or hotel keeper's permit and take advantage of their proximity to the national park before they got squeezed out by "new men who may wish to take holt of this business." [10] Two men, Henry Carter and Walter A. Ashford, used their seasonal residency on the Longmire property inside the national park as reason to be preferred over the others. Another, Henry S. Hayes of Ashford, tried to use Washington Senator Addison G. Foster's influence with the Secretary of the Interior. A third party, Joseph Stampfler, claimed to have fourteen years of experience as a guide associated with the Longmire operation. A fourth, John L. Reese of Ashford, requested a permit and two-acre lease to continue his tent hotel at Camp of the Clouds. [11] The secretary apparently responded to all of these applications in the same way: until Congress appropriated funds for the administration of the park, he would not issue rules or regulations or permits. [12]

More troubling was a 1902 report from a forest ranger to the forest superintendent of Mount Rainier Forest Reserve, routed through the Commissioner of the General Land Office to the secretary, which alleged that John S. Hayes was charging pack trains and tourists a toll for using the trail from Longmire Springs to Paradise Park. A private toll obviously violated the spirit of the law in setting aside a public park. Underscoring the fact that the national park was under the Secretary of the Interior's direct authority and not the General Land Office's, Commissioner Bing Hermann allowed that he had only had the matter investigated because he mistakenly believed the trail lay in the forest reserve. "Inasmuch as the administration of national parks is under your immediate jurisdiction," Hermann wrote to Secretary Hitchcock, "this matter is referred without recommendation." [13] Soon afterwards, the Department of the Interior informed locals, including the Longmires, that no tolls could be collected in the national park. [14]

Aside from the problem of regulating local entrepreneurs who sought to provide services to the visiting public, the campers themselves required supervision. With some 500 people camping at Paradise Park each summer, it quickly became evident that the public must be given some guidelines about how to make camp or else the fragile meadow and its small stands of alpine firs would soon be laid to waste. Even the Sierra Club needed to be educated. The club's secretary, William E. Colby, wrote to the Secretary of the Interior in 1905 for permission for his group of 150 to 200 people who would be camping at Paradise Park to "cut half a dozen or so small trees for poles for our large tents and tables." [15] Apparently the club had received permission to do this the previous year in Yosemite. Acting Superintendent Grenville F. Allen pointed out to Colby that this would set a ruinous precedent and refused the club permission. [16] That summer, Allen ordered the arrest of another camper, Henry Beader of Tacoma, for cutting green timber in Paradise Park. Although the charges were dropped, Allen thought the arrest had made the correct impression on the public. [17] What was becoming clear from these encounters was that the camping public, no matter how well-intentioned, needed direction from park rangers or else it would unwittingly destroy the natural conditions" that the park was intended to preserve.

|

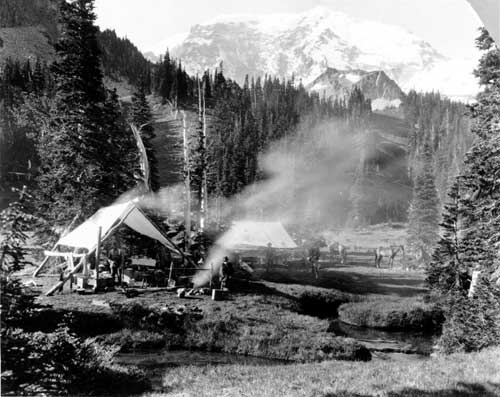

| Campers at Mystic Lake. Note the timbers that have been cut and used for tent poles. (Asahel Curtis photo courtesy of University of Washington.) |

Sport hunters were another concern. Most campers expressed strong support for the principle that there should be no hunting in the national park. Most sportsmen did not disapprove of it either, for they still had an opportunity to shoot the deer and elk that inhabited Mount Rainier when these animals left the park for their winter range. Inside the park, the biggest threat to wildlife came not from sport hunters but from local settlers or "pot hunters" who would enter the park in the fall after the tourists were gone in order to procure wild meat for their larders. Efforts to deal with this problem are discussed in a later chapter on the protection of resources; suffice it to say here that increasing visitor use of the park did bring into the area a small number of sport hunters who were either ignorant or contemptuous of the hunting ban. This problem appears to have been limited to the more remote Carbon River section, where some locals kept hunting dogs outside the park and were "always ready, for a small remuneration, to assist the more disreputable sportsmen of Tacoma and Seattle in their hunting expeditions." [18]

Additional problems related to visitor use arose with the coming of the day visitor a few years after the establishment of the park. It would be difficult to overstate the significance of the day visitor on the development of national parks, especially Mount Rainier National Park. The day visitor had very different needs and expectations from either the camper or the hotel sojourner. Park administrators would never be entirely comfortable with the day visitor. How this kind of tourist could be satisfied with a quick look around in a place of such sublime beauty and natural interest would always be something of a mystery to park staff. Yet, while the left hand tried to slow down the day visitor, the right hand inevitably catered to his or her breathless pace. In the era before the advent of the National Park Service, day visitors were known as "transient tourists." The fact that park superintendents were required to record the relative numbers of "transient tourists" and "people who camped in the park for three or more days" indicates at least a degree of bafflement about how to deal with these two distinct user groups. [19]

The day visitor first appeared in Mount Rainier National Park in the summer of 1904, following the completion of the Tacoma and Eastern Railroad to Ashford, and the simultaneous inauguration of a connecting stage service over the remaining thirteen miles to Longmire Springs. These transportation improvements made it barely feasible for tourists to travel from Tacoma to Mount Rainier and back in one day. In the long run, however, the excursion train was far less important than the automobile in bringing the day visitor to Mount Rainier. In 1907, three years after the first train load of visitors entered the park, the first convoy of automobilists were motoring up the newly constructed government road to Longmire Springs. In 1910, nearly twice as many people came to Mount Rainier by car as by train and stage. Automobilists held the advantage over train passengers in numbers even as the outbreak of war in Europe brought a huge increase of out-of-state tourists to Mount Rainier in 1915. Not everyone who came to the park by car turned around and went home the same day, of course. [20] But if the correlation between automobilists and day visitors was not perfect, it was well known that the train passenger was much more apt to sojourn at a hotel than the automobilist.

Park administrators greeted the advent of the automobile in Mount Rainier National Park with ambivalence and uncertainty. On the one hand, they recognized that cars were the wave of the future. They were well aware that Pierce County was spending as much on improvement of the road from Eatonville to the park boundary as the federal government was spending on reconstruction of the road from the boundary to Longmire Springs. [21] They were able to read the signs of the automobilists' growing political clout in the success of their "good roads movement" in Washington state. [22] On the other hand, they saw problems that the national park should not necessarily entertain. Acting Superintendent Grenville F. Allen thought automobiles should be prohibited from the park for the time being, arguing that "the presence of these contrivances would be a source of great annoyance and some danger to the public generally." [23] And the Secretary of the Interior seemed prepared to issue an order to that effect in 1907. [24] Instead, bowing to pressure from the automobile clubs, the secretary authorized Allen to open the park to cars, and 117 permits were issued in the first season (1908).

Regulations governing automobile use in the park appeared the following March. The regulations held automobiles to a speed limit of six miles per hour, except on straight sections where no horse teams were visible, where the speed limit was fifteen miles per hour. Teams always had the right of way over automobiles, and when teams approached, the automobile driver was to take a position on the outer edge of the roadway and remain at rest until teamsters were satisfied as to the safety of their teams. Each automobile required a permit from the superintendent. Use of the automobiles in the park was restricted to the hours of 8:00 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. and further restricted above Longmire Springs to the hours of 9:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. and 3:30 p.m. to 5:30 p.m. [25] Clearly, cars were admitted into the park with a great deal of trepidation. It is worth noting that Mount Rainier National Park was the first national park to admit cars; cars did not enter Yellowstone for the first time until 1910.

The biggest concern over automobiles was the safety of visitors. The road contained innumerable blind curves and steep embankments and many narrow bridges. Even the rutted and muddy surface of the road required the driver's vigilance. As Superintendent Allen remarked, there would be no particular danger if automobilists observed the speed limits, hours, and rules for passing. But there were violations and accidents. One car went over the side of the road and the driver broke his arm. [26] A stage wagon containing several passengers was overturned in a near collision with an automobile. [27] Automobiles introduced a whole new area of law enforcement into the national park setting. Inevitably, the need to patrol the roadway competed more and more with the care of the popular camping areas. Automobiles tended to make roads the focal point not only of the park's development but of the management of park visitors.

Cars raised questions about aesthetics. It was not that cars were unaesthetic to the non-automobilist, for there were, in fact, very few complaints from the public. [28] Rather, it was an open question whether the automobilist derived more enjoyment from driving his machine than he did from observing the scenery. Officials in the War Department who were in charge of road design and construction thought that the joy of the road should be embraced as an integral part of the nation's new pleasuring ground. [29] But Superintendent Allen, among others, argued that automobile use should be encouraged only insofar as it provided a more affordable means of transportation into the park. [30] Others thought that conservative speed limits in the national park would be sufficient to put automobile drivers in the proper frame of mind. One person admonished readers of the Overland Monthly, "You with your high-power cars may well picture the exhilaration of that ride from Tacoma to the foothills; and it is well to take it while one may, for the foothills reached, the Government road begins and the speed glory must give way to calmer glories of nature." [31] Despite these differences of opinion, however, all agreed that the automobile would change the national park experience; it would change the way people related to nature.

The coming of the day visitor had a pervasive effect on the campers and hotel sojourners in the park. Although people of this era did not phrase it in so many words, day use of an area tended to diminish the area's wilderness quality for those who were camping or sojourning there. Sleeping out in the highcountry or staying at the rustic accommodations at Longmire Springs became an act of volition instead of a requirement; therefore, it too had to be pleasurable. The effect of the "transient tourists" on the people who remained in the park for three or more days was unmistakable: those who mingled with the day visitors at places such as Longmire Springs and Paradise Park demanded better and better accommodations for their overnight stay, while those who really wanted to enjoy a primitive camping experience had to go farther and farther afield from the park road. This was the beginning of the division of the national park into "front country" and "backcountry."

From the perspective of the late twentieth century, it might seem that the day visitor had a more adverse effect on the camper than on the hotel sojourner. Certainly in recent times the inundation of Mount Rainier National Park with day visitors has challenged the ingenuity of park administrators in being able to provide enough backcountry solitude to satisfy the seekers of wilderness. But in the period from approximately 1910 to 1930, quite the opposite was true. Park administrators were chiefly concerned with upgrading facilities in the front country in order to improve the experience of hotel guests and car campers. Not only did the new ease of travel between Mount Rainier and the Puget Sound cities bring more people into the park on weekends than the hotels and tent camps could accommodate, but the appearance of so many people out for a day in the country made the hotels seem unbearably shabby and the few services that were available inadequate. Park administrators seemed aware of the fact that "transient tourists" were in some ways undermining the experience of those who remained in the park for two or more nights. Their solution was to develop the park with first-class hotels and other amenities of the city. Yet such improvements could never be made fast enough. If hotel guests and front country campers still composed the most numerous group of park users in this era, they were also the hardest to satisfy.

LODGING AND OTHER SERVICES: A CHANGING DEMAND

Tourist facilities in this era were confined to the south side of the park and consisted of two hotels and two tent camps. The Longmire Springs Hotel and the National Park Inn were both situated at Longmire Springs, while tent camps could be found at Paradise Park and Indian Henry's Hunting Ground. In addition, the Department of the Interior issued permits to a medley of shopkeepers, transportation companies, and guide services, most of whom hung out their shingles at Longmire Springs. Taken as a whole, these tourist facilities proved unsatisfactory to the public. The park administration would place all visitor services under a single park concession after 1916.

Longmire Springs Hotel

At the time Mount Rainier National Park was created, the Longmire family had already pioneered a tourist business at the foot of the mountain. James Longmire, the family patriarch, had led the first wagon train over Naches Pass in 1853, settled with his wife and children at Yelm Prairie, near Olympia, and guided both the Stevens-Van Trump-Coleman party and the Emmons-Wilson party to the base of Mount Rainier on the first two successful ascents of the mountain in August and October 1870. After his own first ascent of Mount Rainier with Bayley and Van Trump in 1883, James Longmire discovered the mineral springs and natural clearing that would later bear his name and conceived the idea of developing the springs as a resort. By 1885 he had cleared a trail up to it, built a cabin, and was accommodating a few adventuresome visitors. By 1889, Longmire had some guest cabins and two bathhouses completed and was advertising "Longmire's Medical Springs" in a Tacoma newspaper. The next year he opened a small, two-story hotel with a lobby downstairs and five guest rooms on the second floor, and began adding bams and other outbuildings to the property to support a growing outfitting business for parties of campers or climbers who were heading on up to Paradise Park. In the 1890s, this old denizen of the mountain built the original wagon road to Longmire Springs. He supported the movement to create a national park, though he did not live to see it accomplished. He died in 1897. [32]

The Longmire Springs Hotel became an anomaly as soon as the national park was created. Now under the management of James Longmire's son Elcaine and his wife Martha, the hotel and bathhouses occupied an 18.2-acre mineral claim which James had patented in 1892. It was the only patented land within the national park. Proponents of the national park generally assumed that the federal government should acquire this land. Some distrusted the Longmires, considered their mineral claim to be fraudulent, and thought the federal government should purchase the property and then lease it to a hotel operator in order to protect the public from the Longmires' "extortionate" prices. [33] Others thought the Longmires were running a credible operation. [34] In 1902, the Secretary of the Interior declined an offer by James Longmire's widow, Virinda, to sell the property to the government for $60,000. [35]

Relations between the Longmires and the government began to sour in 1905 after the government provided the Tacoma and Eastern Railroad Company with a five-year lease of two acres immediately south of the Longmire claim on which to build a second hotel. The Longmire family now tried several stratagems that were intended either to hold their new competition at bay or to persuade the government to buy them out. First, Robert Longmire opened a saloon on the property. Acting Superintendent Grenville F. Allen thought the saloon would be a "public nuisance" and immediately closed the place down. Robert appealed to Senator Francis W. Cushman for help but Cushman was unsympathetic and the saloon apparently remained closed. [36] Next, Virinda Longmire filed for a 160-acre homestead claim around the 18-acre mineral claim. She argued that her husband had built their original cabin some distance apart from the mineral springs in the belief that he could make a homestead claim, only to find out that a homestead claim could not be made on unsurveyed land. Now the land was surveyed and the cabin did not fall within the 18-acre mineral claim. Acting Superintendent Allen interceded at the General Land Office, and the application was denied. Virinda tried unsuccessfully to appeal it. [37]

|

| Longmire Springs Hotel. The earliest tourist accommodations predated the national park. (Crawford Scrapbook photo courtesy of University of Washington.) |

While this case was under appeal, the Longmires enclosed a small portion of the desired homestead claim with a rough fence and pastured some stock there. Once again, Acting Superintendent Allen found the Longmires' action objectionable. He recommended that Elcaine Longmire be informed that the family could not graze stock on this tract and that the fence be destroyed or confiscated by the government. Finally, after the secretary of the Interior denied Virinda's appeal in the spring of 1907, Allen directed a ranger to evict Elcaine from the cabin located on the tract in question and then burn the cabin. Elcaine apparently tried to forestall this action by encouraging his sister-in-law, Susan Hall, to occupy the cabin with her children that summer. But the following winter, Ranger H.M. Cunningham went up to the Longmire property, found the cabin empty, and burned it down. Cunningham reported to Allen:

I did this at night so as to avoid any possible personal conflict with the Longmires. They—Ben and Elcaine Longmire—were still staying at the Springs on their patented land. I was on good terms with them and they had not said any thing about resisting the removal of the cabin, but I do not think they were staying at the springs so late in the season for any other purpose than to prevent the removal of the cabin. They had removed their effects from the homestead cabin long before —about the first of August. [38]

This ended the Longmires' attempts to expand the property.

If the Longmires had been concerned about losing business to the Tacoma and Eastern Railroad Company's new hotel venture, they soon discovered that the increasing tourist travel to the park was more than even the two hotels could accommodate. They built an addition to the hotel, making a total of twelve guest rooms, and erected tents behind it. During the 1908 tourist season the Longmire Springs Hotel registered 925 guests, or nearly one-third of the total park visitation for that year. [39]

Park administrators characterized the Longmire Springs Hotel as a second-class hostelry. Noting that its rates were somewhat lower than those of the neighboring National Park Inn, they considered the hotel an advantage to the public. But they regretted the shabby appearance of the place which, being on private property, they could do nothing about. The buildings were very rough, and the wire fence which ran around the property was hung with signs and advertisements. The little shanty that had served for a short time as a saloon had been turned into a pool hall. [40] There were rumors, year after year, that the Longmires planned either to refurbish or sell the enterprise, but as the place only deteriorated it became more and more of an embarrassment. Finally, in 1916, the family leased the property to the Longmire Springs Hotel Company, which made the long-awaited improvements the next year. These included a new two-story, seventeen-room hotel, sixteen new cottages in place of the tents, and a new sulphur plunge. In 1920, the Rainier National Park Company bought the lease and made a twenty-year contract with the family. The original hotel was burned, and the new building was moved across the road where it became the National Park Inn Annex. [41] The Longmire family would eventually sell their vacant property to the government in 1939.

National Park Inn

Mount Rainier National Park's second hotel, called the National Park Inn, opened for business on July 1, 1906. The long, two-story building, located opposite the Longmire Springs Hotel, contained thirty-six rooms and had a capacity for sixty guests. On the grounds beside the building a number of tents with wood floors, walls, doors, and electric lights could accommodate another seventy-five guests. The National Park Inn's modern physical plant consisted of an electric lighting and refrigerating unit powered by water from the Nisqually River. Built and operated by the Tacoma Eastern Railroad Company, the hotel provided elegant meals supplied by the commissary of the Chicago, Milwaukee and Puget Sound Railway Company in Tacoma, and generally tried to be a first-class hotel. This gave park visitors a choice between upscale hotel service and the rustic Longmire establishment across the road. As one writer compared the two,

There are two hotels here, one catering to plain and simple abundance, the other boasting a French chef. With a big bonfire on the grounds one appeals to the love of out of doors; while the other entertains the guest through the evening with music before the open fire-place in the social hall. There are the usual hotel accommodations, and also the well patronized tents in connection. Across from the hotels are the springs, iron and sulphur bubbling side by side.

There are, of course, bath houses, and this is a resort to which many come for a day, or a week, or a month, and some never go further. It satisfies them. [42]

Unlike the Longmire Springs Hotel, the National Park Inn occupied leased ground and operated under contract with the government. The contract was the responsibility of the Secretary of the Interior, who was still feeling his way in this area of national park policy. The legal arrangements for hotel concessions seemed to require a balancing act between the need to maintain control of the operation on the one hand and the need to attract sound investment capital on the other. Secretary Hitchcock did not want Mount Rainier National Park to be the graveyard for a string of undercapitalized hotel enterprises, nor did he want to turn all the tourist business over to a railroad monopoly. His choice of the Tacoma and Eastern Railroad Company was safe and politically astute because it was a well-capitalized subsidiary of the Milwaukee Road and already had a large investment in its line from Tacoma to Ashford, yet had a local cast. Refusing the company's request for a fifty-year lease, Hitchcock wisely held the company to a five-year lease, which could be renewed subject to modifications that the government saw fit to make. [43]

The concession got off to a bumpy start. Just weeks before the National Park Inn was set to open, both Secretary Hitchcock and Acting Superintendent Grenville F. Allen received letters from one John S. Kloeber, implying that he had an unauthorized sublease agreement with the Tacoma Eastern Railroad Company. Kloeber wanted permission to graze horses on the property and to serve hard liquor. Hitchcock directed Allen to refuse both requests, and then stated as a matter of policy that the Department would not recognize anyone in the management of the hotel other than the lessee, nor permit the lessee to sublet any part of the lease. Evidently embarrassed, the Tacoma Eastern's Vice President John Bagley denied that the sublease with Kloeber had ever been finalized. [44] Nevertheless, Bagley hired Kloeber to manage the new hotel during its first three seasons. Kloeber never won the confidence of Acting Superintendent Allen. Perhaps at Allen's suggestion, the company replaced Kloeber with a new manager in 1909. [45]

There were a number of other minor problems with the original concession contract that the Secretary of the Interior sought to correct when it expired in 1911. First, federal officials had found that they had too little control over the construction and maintenance of the buildings. Although the company had submitted drawings of its proposed hotel in 1905, no specifications had been written into the contract. Allen had not been entirely pleased by the appearance of the National Park Inn. He found the main building "rather attractive," but complained that the grounds were "ill kept and disfigured by rough unpainted buildings used for stables and other purposes. [46] In the new contract, the Secretary of the Interior required the Tacoma Eastern Railroad Company to submit a detailed list of improvements and repairs that it expected to make over the next five years. [47]

Another deficiency in the original contract was its lack of provision for a sublease. The railroad company proposed to set up a holding company, the National Park Inn Company, to run the park concession. The Secretary of the Interior required that a copy of this holding company's articles of incorporation and a list of its stockholders and officers accompany the new lease agreement. [48]

The Secretary of the Interior also added to the contract a "usage tax," assessed at the rate of twenty-five cents per guest during the season, to be paid to the U.S. Treasury at the beginning of the following season. This was modelled on the contract with the Yellowstone Park Hotel Company. The usage tax was on the order of $400 per year, whereas the original lease involved a flat fee of only $100 per year. Finally, the secretary required metes and bounds for a 2-acre addition to the leased tract at Longmire Springs, and for a 7.1-acre tract in Paradise Park on which the company proposed to build a second hotel. The Paradise Park plan was later dropped. [49]

The visiting public knew nothing of such refinements in the concession agreement, of course, but it did demand one other change: an improvement of sanitary conditions at Longmire Springs. The National Park Inn maintained that the bath houses and rundown hotel across the road were the source of visitors' complaints. As early as 1909, however, Superintendent Allen had complained that the National Park Inn's kitchen disposed of waste in the Nisqually River, and had recommended that the company be required to do something else with its garbage. Two years later, Asahel Curtis of the Seattle Chamber of Commerce reported on the unsanitary conditions found at the park, noting specifically that "large piles of manure are taken out of the stables at Longmire Springs and scattered over the ground." [50] In the fall of 1911, Superintendent Edward S. Hall had a sewer system installed at Longmire Springs and required both hotels to put in connecting lines.

Ironically, these improvements may have served to heighten public concern that conditions in the park were unsanitary. In the spring of 1912, there were rumors that typhoid fever prevailed in the park. The National Park Inn Company feared that the rumors would depress business and wanted to find the source of the reports. Superintendent Hall knew of only one case of typhoid fever in the park, though many cases of dysentery had been reported at Longmire Springs and in the tent camps, as well as in all the towns from Ashford to Eatonville. [51] It seemed that the crowded conditions in the mountain camps and in the overflow tent accommodations at the two hotels in Longmire Springs were making a poor impression on the public. The tent camps and hotels had become, in Hall's words, "entirely inadequate" to accommodate the increasing number of visitors to the park. [52]

Camp of the Clouds

Most visitors to Mount Rainier in the 1890s and early 1900s were not content to end their trip at Longmire Springs or even the Nisqually Glacier; they wanted to break out of the timber and experience the panoramic views and wildflower-strewn meadows for which Paradise was renowned. From Longmire Springs they took the trail built by Leonard Longmire and Henry Carter in 1892—paying a small toll for the privilege—and proceeded upwards, usually making rest stops at Carter Falls and Narada Falls on the way. Some made the magnificent timberline park their destination; others passed through Paradise Park on their way to the mountain's summit.

As early as 1895, sufficient numbers of people were visiting the area to give rise to two small business ventures. Charlie Comstock of Elbe, Washington opened a coffee shop, which he called the Paradise Hotel, on Theosophy Ridge, and Captain James Skinner established a tent camp on the east shoulder of Alta Vista. [53] In 1898, John L. Reese of Ashford, Washington combined the tent camp and the meal service into one operation, located on Theosophy Ridge, and named it Camp of the Clouds. [54]

The steady growth of Reese's camp provides a rough index to the increasing popularity of Paradise Park. In 1903, Reese had seven tents and a cook tent. Camp of the Clouds increased to thirty tents in 1906, forty tents in 1909, sixty tents in 1911, and seventy tents in 1914. By then, Reese also had moved the kitchen and dining room into two wood- frame buildings. As the operation expanded, it took considerable effort to pack in supplies in June when the trail was still snow-covered. Encountering snow depths of twelve to thirty feet as late as mid-July, Reese would use horse-drawn road scrapers and dynamite to clear the wet, condensed snow from the tent sites. [55] This hard work was necessary in order to maximize his returns during the short summer season.

Camp of the Clouds received very little supervision from the Department of the Interior. For the first three summers after the national park was created, Reese packed in his supplies and set up camp each July just as he had before. In 1902, at the request of Forest Superintendent D.B. Sheller, Reese obtained a permit for his camp from the Secretary of the Interior. This permit was renewed from year to year until 1916. The permit authorized Reese to occupy two acres on Theosophy Ridge and to provide tents, bedding, and board to tourists. Intermittently, the permit authorized Reese to graze two milk cows and six horses in Paradise Park. [56] Park officials all held Reese in high regard and considered his camp to be an asset not only from the visitors' standpoint but also from the standpoint of protecting the resources. Reese's camp concentrated use in one area, thereby reducing the fire hazard and slowing down the consumption of firewood. Reese himself kept a close watch on campfires and helped enforce the park regulations in the area. [57]

The public was generally satisfied with Camp of the Clouds. There were few complaints about the rates. Despite the camp's relative inaccessibility, Reese's rates remained competitive with those at Longmire Springs. In 1914, they were as follows:

| Two persons occupying one tent, per day, each, with board | $2.50 |

| Two persons occupying one tent, per week, each, with board | 14.00 |

| Tent occupied by one person, per day, with board | 3.00 |

| Tent occupied by one person, per week, with board | 16.00 |

| Breakfast, 50 cents; lunch, 75 cents; dinner, 75 cents. [58] | |

What complaints there were focused on the camp's rustic character and poor sanitation. People wanted nicer accommodations and were willing to pay more for them. Public demand for better sanitation increased in 1911, the first full season that it was possible to take horse drawn vehicles all the way to Camp of the Clouds. [59]

Park officials sometimes acted on visitors' complaints by directing Reese to make specific improvements in the camp's sanitation. Overall, however, they thought Reese was doing very well with what he had. In 1914, Superintendent Ethan Allen defended Reese's camp against a particularly sharp complaint by a Seattle man, Martin Korstad. When the Secretary of the Interior confronted Allen with Korstad's letter, Allen assured the secretary that Reese had made fair progress on the requested improvements. He had added screens to the kitchen and dining room to keep down the insects, and had installed flush toilets (for the women only, promising that more would follow for the men). [60]

Reese sold his camp outfit to the Rainier National Park Company in 1916, which used it to house construction crews as they worked on the new Paradise Hotel. While both the company and the National Park Service would continue to provide campgrounds at Paradise, public interest would focus much more on the first-class hotel after 1916.

Wigwam Hotel

Beginning in 1908, George B. Hall and Susan Longmire Hall ran a second, smaller mountain camp near Indian Henry's Hunting Ground called the Wigwam Hotel. This camp's marginal success reflected more on the access trail than it did on the beautiful setting which the camp occupied. The trail from Longmire Springs to Indian Henry's was approximately the same distance as the trail to Paradise, but it did not enjoy the mystique of the Paradise trail, which led past Nisqually Glacier to the main climbing route up the mountain. Never accessed by road, the camp at Indian Henry's did not grow like Reese's camp but remained fixed at fifteen tents until it was closed in 1916. [61]

Acting Superintendent Grenville F. Allen favored the establishment of this camp for the same reasons that he supported Reese's camp. It would serve the visiting public and assist with the prevention of forest fire and trespass. "The danger from fire is much less when the tourists are provided for at a summer resort than when they are in scattered camping parties," Allen advised the Secretary of the Interior. [62] The Halls' permit was similar to Reese's, involving a year to year "tent camp privilege" on a two-acre tract for a nominal fee of $2 per tent. [63] The permit prohibited the cutting of timber but did allow the grazing of two milch cows and six horses. [64]

Park officials received the same complaints about poor sanitation in this camp that they heard in connection with the Camp of the Clouds. In 1913, Superintendent Ethan Allen supplied the Halls with detailed specifications for improving the kitchen, dining room, tent floors, and toilets, but received no cooperation from them. [65] Allen was evidently piqued by the Halls' "audacity" in maintaining that the camp toilets were adequate, describing the same to the Secretary of the Interior. "These arrangements consist of four poles stuck in the ground in the semblance of a square, and around these poles are drawn 'gunny' sacks. Inside is a bench." The Halls, unable to comprehend how the superintendent could become so worked up over a little backcountry inelegance, suggested that he had a vendetta against them and wanted to drive them out of business. [66] But Allen had a perfectly legitimate motive: park visitors were rapidly becoming more fastidious.

Other Services

Beginning about 1908, the Department of the Interior issued year-to-year permits to numerous smaller business concerns in the park. All of these permits were cancelled after 1916 when the National Park Service determined that the best way to provide visitor services was through a single park concession. These permits were generally granted to individuals. They are of interest for two reasons: first, the services that they provided to the public reveal interesting details about the visitor experience in these early years; and second, in the aggregate, these small businesses created a clutter in the park and an administrative burden which the National Park Service's concession policy sought to do away with.

Most visitors to Mount Rainier National Park in this era had contact with at least one park concessioner. If they took the excursion train to Ashford, they normally held a through ticket to Longmire Springs, boarding one of the Tacoma Carriage and Baggage Transfer Company's wagons or later, one of the company's touring cars to go the remaining thirteen miles. If they came by private automobile or bicycle and did not trust the condition of the road past Ashford, they likely purchased a ride on one of George B. Hall's wagons or pack trains. Both outfits provided this service under permits from the Department of the Interior. [67] If park visitors wanted a ride up the road beyond Longmire Springs, they normally had to take one of Hall's wagons or saddle horses, whose permit was supposed to give him this exclusive privilege. If, however, the park visitors arrived by one of the Tacoma Carriage and Baggage Transfer Company stages, they might have been sold tickets enroute to Longmire Springs for a trip on up the road to Nisqually Glacier and Narada Falls. [68] After 1910, people bound for Mount Rainier could rent a seven-passenger touring car from one of four car rental companies that were licensed to enter the park. [69] Or they could purchase a seat in an eleven-passenger jitney from the DeLape Tours Company ($7 round-trip or $4 one way from Tacoma). [70]

After registering with the gatekeeper at the park entrance (and after buying a $5 license if they came by private automobile, or a $1 license if they were on a motorcycle), park visitors usually proceeded to Longmire Springs, where they found not only the two hotels and their assortment of outbuildings, but an array of tents and advertising signs, too. George Hall leased a large tract for his horses and wagons on which he had a barn and stable. James Patterson ran a barber shop, Fred George had a confectionary and camp grocery store, and L.G. Linkletter sold scenic photographs. [71]

Linkletter not only sold his own photographs, he also took tourists' portraits while they were in the national park. To provide this service he would load his photographic equipment onto his motorcycle and ride to some desired place such as the Nisqually Glacier or one of the scenic overlooks on the road to Paradise, where he would meet, pose, and photograph his clients. He would then return to his workroom at Longmire Springs and develop the pictures for the visitors to pick up as they left the park. In 1915, Linkletter received permission from the Secretary of the Interior to set up a studio for this purpose at the foot of the Nisqually Glacier, despite Superintendent Allen's opinion that it would mar the scenery. [72]

Linkletter's permit, however inconsequential in itself, was emblematic of the problems that the Department of the Interior faced in managing park concessions in this era. During the time that Linkletter carried on his summer business in the park, a rather large correspondence accumulated between this University of Washington instructor and the Department of the Interior. Some of the correspondence concerned the makeshift appearance of Linkletter's shop, which appears never to have evolved beyond the original canvas-walled tent. [73] Most of the correspondence dealt with Linkletter's competition. Linkletter believed that his license carried an exclusive privilege to sell photographs in the park, and he complained whenever photographs were sold at the National Park Inn, Camp of the Clouds, Wigwam Hotel, or even outside the park if the scenes were of Mount Rainier. [74] Concerning both issues—building standards and business competition—a virtual absence of policy made it difficult for the Department to deal effectively or coherently with the steady stream of hassles that arose from the Linkletter permit.

The difficulties of managing competition in the park extended to the transportation concessions as well. The Department of the Interior tried to prevent the Tacoma Carriage and Baggage Transfer Company from monopolizing the service between Ashford and Longmire Springs by giving George Hall an exclusive privilege above Longmire Springs; this proved difficult to enforce. [75] An assistant to the Secretary of the Interior considered a proposal to require $100 licenses for rental cars to match the $100 licenses for jitneys, but rejected it for "administrative reasons." [76] In 1916, the National Park Inn Company tried to wrest business away from the Tacoma-based jitney drivers, saying that it needed the "full transportation concession or this property loses its value." [77] The picture that emerged from all of this was one of chaos and drift. The Department of the Interior lacked clear policy guidelines to assess what developments were in the public interest, how much each business should pay for the privilege of operating inn the park, and whether or not each concession carried an exclusive privilege. The Department of the Interior made little progress toward a consistent approach to park concessions in this era, but dealt with them instead in a piecemeal fashion. [78]

ROADS AND TRAILS: A CITIZEN EFFORT

When Mount Rainier National Park was created, federal officials generally assumed that private enterprise would take the lead in developing visitor services while the government would undertake the more expensive task of developing roads and trails. In the early years, the government divided up responsibility for roads and trails between two executive departments. The War Department oversaw the work of surveying and constructing the park road, while the Department of the Interior handled road maintenance and all trail development.

But Mount Rainier had a tradition of local initiative in road and trail development that pre-dated the park, and this tradition carried into the park's early years. Notable citizens' accomplishments included the clearing of trails, the construction of a shelter cabin at Camp Muir, and the making of preliminary road surveys. While all of these achievements paled in comparison to the government's work of building the road to Paradise (see Chapter V), they nevertheless contributed to the development of the park. Moreover, these developments were more important for their political than their practical significance, for they tended to reinforce the sense of proprietorship with which many people in Seattle and Tacoma viewed Mount Rainier National Park.

One private citizen came to personify this tradition of local initiative and proprietorial interest in the development of the park. He was Asahel Curtis of Seattle. Like his better known brother Edward, Asahel Curtis was a professional photographer. Both the Curtis brothers began their professional lives selling scenic photographs of Mount Rainier, Edward moved on to win fame for his portraiture of American Indians, while Asahel remained in Seattle to become locally famous for his Pacific Northwest landscapes, particularly his picture albums of Mount Rainier. More to the point, Asahel Curtis came to thrive on the politics of scenic preservation. For years he served as chairman of the Seattle-Tacoma Rainier National Park Committee (later the Rainier National Park Advisory Board). He is an interesting figure in the administrative history of Mount Rainier National Park because he left an ambivalent legacy after nearly three decades of involvement in the development of the park. He combined an artist's appreciation for the scenic beauty of Mount Rainier with a businessman's keenness for boosting the park and making it into one of the Pacific Northwest's great attractions. Sometimes a friend of the park administration and other times a burr under its saddle, Curtis was easily the most active and informed private citizen during the first fifty years of Mount Rainier National Park's existence.

Although Asahel Curtis applied unsuccessfully for the position of park superintendent in 1918, he seemed to enjoy his role and vantage point outside the government. [79] Active in The Mountaineers during its founding years, he might have dominated that organization had the club not already been under the capable leadership of Professor Edward S. Meany. Instead, with T.H. Martin of Tacoma, Curtis co-founded the Seattle-Tacoma Rainier National Park Committee in 1912, an organization dedicated to the "development and exploitation of Mount Rainier National Park." [80] For many years, Curtis straddled the increasingly divergent philosophies of these two organizations. In the 1920s and 1930s, he came more and more to represent the business interests of Seattle and Tacoma in demanding further road development in the park while The Mountaineers called for less. Then, in the mid-1930s, Curtis parted company with The Mountaineers, the National Park Service, and even his fellow members on the Rainier National Park Advisory Board when he opposed the establishment of Olympic National Park. This breach severely compromised the Rainier National Park Advisory Board and effectively ended Curtis's influence on the development of Mount Rainier National Park.

Though his legacy was mixed, Curtis's vision for the park's development was remarkably consistent. His ideas were already discernable in 1908-09, when he organized and led the third annual outing of The Mountaineers. On this outing about seventy-five Mountaineers set out from the Northern Pacific railhead at Fairfax and went up the Carbon River to Moraine Park, on the north flank of the mountain, from which they made an ascent of the summit by way of the Winthrop and Emmons glaciers. [81] For Curtis, the expedition had a definite public purpose: to bring publicity to the north side of the mountain. "It is the hope of the club to not only open this region for the Mountaineers trip," Curtis wrote, "but to do as we have done with the Olympic mountains and Mt. Baker, permanently open the north side of the mountain to tourist travel." [82] Even the elaborate preparations for the expedition had a promotional quality, as Curtis reconnoitered the route in 1908 and recommended trail improvements to the acting superintendent. Curtis also sent a prospectus to the Sierra Club, dangled the club's list of supplies before a couple of prospective packers, and solicited support from the Pierce County Board of Commissioners for trail repairs outside the park boundary. [83] Shortly before the trip, Curtis invited Secretary of the Interior Richard A. Ballinger to join The Mountaineers' camp at Moraine Park while he was out west that summer. "We will be camped for three weeks on the Northern side of the mountain, in a region that has not been visited by many people for years, and it is a region that we feel deserves more attention than it is receiving at the present time in comparison with the Southern side." [84] Curtis wanted to make the national park accessible from all directions so that it would benefit all the people of the state. [85] He wanted The Mountaineers to get behind the effort to induce easterners to take vacations out west rather than abroad. [86] And with other preservationists, Curtis wanted to spread what John Muir called the "glacier gospel"—the secular faith that nature appreciation humbled and improved the human spirit. In his account of the Mount Rainier outing, Curtis wrote:

He is a poor mountaineer indeed who has not returned to his home the better for the many lessons learned in the solitudes. The trivial things of life; the petty cares that to us seem so great slink back in the presence of this majestic mountain. It is as if one heard from out the solitudes a voice: "Why all this haste? Why all this fret and care? A thousand years ere your impatient feet first trod the earth this same beauty smiled, unknown to man. The same flowers bloomed content to bloom and die, adding their mite to nature's hoard of mold. The same streams of ice coursed their way down mountain slopes in awful majesty. A thousand years after your slumber in that last great sleep, your petty deeds and purposes unknown bear their message to other sons of man, who as restless and resistless as yourself found here a curb to their impatient witless will. [87]

It was a unique feature of this era that a man like Curtis could express both the glacier gospel of John Muir and a kind of chamber-of-commerce boosterism without the least bit of cant in either case.

In 1910, Curtis helped organize a committee of The Mountaineers on Mount Rainier National Park. The committee sought the appointment of a park superintendent, government licensing of mountain guides, and the construction of a climbers' shelter at Camp Muir. It succeeded in the first two objectives within the year; the shelter took a little longer. Superintendent Edward S. Hall, appointed that fall, was the first park superintendent able to devote all his energy to the park. (His predecessor, Grenville F. Allen, was forest supervisor of the Mount Rainier Forest Reserve as well.) In his annual report for 1911, Hall described the newly implemented guide system:

Four persons were authorized to act as guides in the park during the season of 1911, one of whom was not permitted to guide to the summit of Mount Rainier nor across any glacier. Those authorized to guide to the summit are mountaineers of known ability. . . .While the present guiding system in the park is crude compared with that of the Swiss Alps, the number and class of tourists attempting the summit does not appear to warrant, at this time, a system and regulations that would add greatly to the expense of making the ascent, but the number in each party should be limited to eight persons. [88]

The recommendation of a shelter at Camp Muir had been made more than a decade earlier after the first climbing fatality on the mountain, and had been renewed in 1908 by Major Hiram Chittenden of the Army Corps of Engineers. [89] The Mountaineers committee suggested two climbers' shelters, the first to be erected at Camp Muir and a second to be built at a later time on the wedge between the Winthrop and Emmons glaciers (Steamboat Prow). Two years later, Curtis informed Superintendent Hall that "a well known man of the state" was prepared to donate funds for the construction of a shelter, and the Interior Department approved the plan, but it never materialized. [90] About three years later, in March 1915, The Mountaineers took up the issue again, this time with the desire to commemorate the recently deceased naturalist and Sierra Club founder, John Muir. With the enthusiastic support of Stephen T. Mather (then an assistant to the Secretary of the Interior), the shelter was constructed in 1916 at a cost to the government of $573.00. It was built according to specifications provided by club member Carl F. Gould. [91]

While The Mountaineers were accomplishing these limited objectives through the cooperation of the Department of the Interior, Curtis had begun to think more grandly about a system of park roads. In 1911, he received advice from Secretary of the Interior Walter L. Fisher that the full program of road and trail development that he had in mind would require action by Congress, and that he ought to "take it up with the people in the State of Washington who are interested and see what can be done to secure from Congress the necessary legislation and appropriations." [92] Armed with this letter from the secretary, Curtis contacted prominent individuals in the business communities of Seattle and Tacoma, and persuaded them to lay aside their mutual suspicions and rivalry to form an intercity committee on Mount Rainier National Park. The committee appointed Curtis as chairman and T.H. Martin, a Tacoma businessman, as secretary. Its member organizations included the Seattle Commercial Club, New Seattle Chamber of Commerce, Tacoma Chamber of Commerce and Commercial Club, Rotary Club of Seattle, and Rotary Club of Tacoma. "An important part of our work," Curtis announced to Secretary Fisher in March 1912, "will be an effort to have Congress authorize the construction of trails and roads and to appropriate funds for that purpose. In this I believe that the united action of Seattle and Tacoma will have much greater weight than their divided action has had in the past." As the work proceeded, Curtis added, the committee would "bring in other parts of the state interested in the park." [93]

The Seattle-Tacoma Rainier National Park Committee proposed a nine-point program of development. It called for surveys of a complete system of roads and trails; improvement of the south-side road and its extension to the eastern boundary of the park; roads from Longmire Springs to Indian Henry's Hunting Grounds and from the Carbon River to Moraine Park and Spray Park; protection of timber in the national forests along the approach roads to the park; a better sanitation system; a climbers' shelter at Camp Muir; a better system of park patrol; and the establishment of a "Bureau of National Parks." The nine-point program was signed by representatives of all the member organizations. [94]

In December 1912, the committee appointed Samuel C. Lancaster of Seattle to lobby in the national capital for the desired park appropriation during the upcoming short session of Congress. As soon as he arrived in Washington, D.C. in January 1913, Lancaster began laying the necessary groundwork with all of Washington state's senators and congressmen. Lancaster scored his greatest success when he obtained a meeting with President William H. Taft. The President showed a keen interest in the committee's program for the development of Mount Rainier National Park. Fortuitously, he had first-hand knowledge of the park and the government road from his visit to Mount Rainier in October 1911. After Lancaster's visit, Taft directed Secretary Fisher to prepare a supplementary estimate of $175,000 for Mount Rainier National Park—$25,000 for surveys and $150,000 for road construction—and rush it to the Senate before the Appropriations Committee ended its current deliberations. Congress balked at the administration's last minute correction, and approved a mere $10,000 for road surveys over and above the administration's original request of $13,400 for salaries and maintenance. Still, despite this disappointment, Lancaster and the Seattle-Tacoma Committee looked forward to larger appropriations in coming years. It was also a valuable learning experience; henceforward, the committee would take pains to track the budget process from its inception, beginning with the park superintendent's estimate to the Secretary of the Interior for the following fiscal year. [95]

But the committee did not stop there. With the approval of Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane, who visited Mount Rainier National Park in August 1913, it hired two experienced road engineers to prepare plans and cost estimates for the completion of the park road system. On the basis of the road engineers' report, the committee recommended an estimate of $43,708 for the first year's road work and $12,500 for survey of a north-side road, both to be included in the budget for 1914. It recommended further that the road to the east boundary of the park follow a low-elevation route, beginning at a point near Longmire Springs and proceeding through the Cowlitz Valley to the Ohanapecosh Valley, then up the east boundary of the park to a point near the center, where it would connect (over Chinook Pass) with a state and county road out of Yakima. (The latter road was now under construction and was supposed to be completed to the east boundary of the park in 1914.) Because this low-elevation route went south of the park into the national forest, the committee also recommended a revision of the park boundary to encompass it. [96]

The details of the Seattle-Tacoma Committee's road survey were less important than the fact that the committee had had one made. The committee members well knew that the Department of the Interior had its own surveyors' reports; Inspector E.A. Keys had prepared detailed specifications for widening and macadamizing the road to Paradise in 1911, and a survey of the proposed road from Longmire Springs to the east boundary of the park was already funded under the sundry civil appropriation act of June 23, 1913. [97] These reports, not the report by the committee, would serve as the basis for a park road construction program. But the work of the committee put pressure on Congress to act. It added weight to the Interior Department's appropriation request for Mount Rainier National Park when that request was stacked against others for Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Glacier. This was one of the lessons that the committee had learned from its lobbyist in Washington, D.C. The national parks were all on their own, each one relying on its own small circle of support to educate members of Congress about its needs. Other parks, such as Glacier and Grand Canyon, enjoyed a great deal of "free" advertising by railroad companies. In the competition for congressional funding, publicity and demonstrable local support were critical. [98]

It was to end this bidding war between the national parks that so many local groups like the Seattle-Tacoma Committee avidly supported the establishment of a Bureau of National Parks. Lancaster pushed this idea when he returned from Washington, D.C. in 1913. "Our Inter-City Committee should co-ordinate and co-operate, or get into actual working touch with similar bodies in the cities of Denver, Salt Lake City, Reno, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Oakland, Phoenix, Santa Fe, Albuquerque, El Paso, Oklahoma City, Cheyenne, Boise, Portland, Spokane, Helena and possibly Hot Springs Arkinsaw [sic]," Lancaster advised the committee. [99] Together, they would put forward the following program:

- Adequate representation on the necessary congressional committees, especially House appropriations.

- Adequate appropriations for all the national parks.

- A complete study of the "See America First" movement, bearing in mind estimates that Americans vacationing in Europe spent some $400,000,000 to $600,000,000 annually.

- Establishment of a Bureau of National Parks.

As Lancaster envisioned it, the sole purpose of the Bureau of National Parks would be to publicize the national parks through traveling photograph exhibits and a staff of public lecturers. A federal bureau with responsibility for advertising the parks would tend to level the playing field.

The great Northern Ry. is expending money freely to advertise Glacier National Park, and is getting practical results. The Northern Pacific has done the same thing for Yellowstone, and other transcontinental lines are working for Yosemite, the Grand Canyon and other parks. All of these forces should unite as suggested with the commercial bodies of the cities named, and by co operating, these National Recreation parks can be made to yield results as yet but little dreamed of. . . .The Swiss Government has learned this lesson well and they are selling more scenery each year than any country of like area. . . .We must meet this competition. The State of Washington has scenery that fully equals that of Switzerland; we only need to make it accessible and to see that our guests are comfortably cared for when they come to visit us. [100]

The movement for a Bureau of National Parks found its champion in Stephen T. Mather, the California mountain climber, national park enthusiast, and self-made millionaire who accepted Secretary Lane's famous offer in 1914 to come on down to Washington and run the parks himself. [101] Mather quickly assumed leadership of the double-barrelled effort to get more people into the national parks and to get Congress to enact legislation that would establish a new bureau in charge of them. In 1915, Mather visited Mount Rainier on his tour of the national parks, where he was joined by members of the Seattle-Tacoma Rainier National Park Committee on a pack trip around the rugged west side of the mountain. Camped at Spray Park under a brilliant full moon, the party listened with rapt attention to a recitation of a Robert Service poem by Asahel Curtis. The next day they descended to the Carbon River and followed it out of the park. Afterwards, Mather gave his pitch to a gathering of business leaders—Thomas H. Martin, Chester Thorne, Henry A. Rhodes, Alex Baillie, David Whitcomb, William Jones, Sidney A. Perkins, Joseph Blethen, Everett Griggs, John B. Terns, Herman Chapin, Samuel Hill, Charles D. Stimson—at the Rainier Club in Seattle, and talked them into forming a Rainier National Park Company and building an inn at Paradise. [102]

Mather's pack trip with Seattle and Tacoma businessmen was not the only notable expedition in the park that summer. About the same time Mather's party was in the park, some ninety Mountaineers with a pack train of fifty horses made a complete circuit of the mountain on what would soon become known as the Wonderland Trail. As Superintendent DeWitt L. Reaburn described it, "The trip around the mountain can be made in about seven days, with an average march of 20 miles over the trail." [103] Mather does not appear to have met with The Mountaineers during his visit to Mount Rainier and the Puget Sound cities. His attention was fixed on getting a modern hotel built at Paradise in order to bring more people into the park, and enlisting local investment capital to accomplish that goal.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 24-Jul-2000