|

MOUNT RAINIER

Wonderland An Administrative History of Mount Rainier National Park |

|

| PART TWO: FOUNDING YEARS, 1893-1916 |

V. RUDIMENTS OF ADMINISTRATION

INTRODUCTION

After passing the Mount Rainier Park Act, Congress showed little enthusiasm for appropriating funds with which to administer the new national park. Not until 1903 was the park placed under the nominal supervision of Mount Rainier Forest Reserve Supervisor Grenville F. Allen, and not until 1910 did the park have its own superintendent. Yet in spite of these limitations, park officials established the rudiments of administration during the first decade and a half of the park's existence. They built up a ranger force, cleared trails, constructed administrative buildings, and strung telephone lines. With the help of the state legislature and Congress, they resolved all doubts about their authority to enforce regulations within the jurisdiction of the park. They helped coordinate the efforts of the General Land Office, the Geological Survey, and the Forest Service on a variety of land issues. These included the disposition of the Northern Pacific's land grant inside the park, the marking of boundaries, the completion of Mount Rainier's first topographical survey, and the maintenance of the park access road where it crossed a three-mile strip of national forest land.

Congress was a little more generous in appropriating funds for road development in the park. As it had in Yellowstone, Congress assigned this work to the War Department. The work included two surveys in 1903-04—one from the west entrance to Paradise, and the other from the east side of the Cascades to Cowlitz Park—followed by construction of the road to Paradise between 1906 and 1910. In 1913, Congress transferred responsibility for the road from the War Department to the Interior Department. The latter agency oversaw the ongoing work of widening, resurfacing, and repairing it.

This chapter examines how the government accomplished the task of building the park's basic administrative organization and infrastructure in the period 1899-1915. It is divided into sections on the development of a ranger force, development of the park road, the problem of jurisdiction, and land issues.

DEVELOPMENT OF A RANGER FORCE

The early national park "ranger" had two lines of ancestry. One line could be traced back to the military troops who were stationed in Yellowstone, Yosemite, Sequoia, and General Grant national parks beginning in the 1880s and 1890s. The military influence was recognizable in the Park Service's early emphasis on a centralized, paramilitary organization. The other line of ancestry went back to the forest rangers who were hired to patrol the forest reserves beginning in 1897. The Forest Service influence could be seen in the development of a ranger mystique that revolved around such nonmilitary virtues as independent judgment, self-reliance, and versatility. As the nation's fifth national park, Mount Rainier confronted government officials, politicians, and preservationists with the choice of employing troops or rangers to enforce the law. Their decisions affected not only Mount Rainier but the emerging national park system as well.

Local preservationists called for troops to protect the Paradise meadows as early as 1893, after the area had been set aside as the Pacific Forest Reserve. [1] At that time Congress had made no provision for the protection of forest reserves, and the only examples of natural reserves that were being protected with force were Yellowstone and the three national parks in California. With these precedents in view, local opinion appeared to favor the use of troops for the protection of Mount Rainier. But no action resulted. These local demands were renewed after 1900. [2]

On December 4, 1901, Senator Addison G. Foster of Washington introduced a bill (S.270) that would have authorized the Secretary of the Interior to request a detail of troops for Mount Rainier National Park. It had the support of Secretary of the Interior Ethan A. Hitchcock as well as Secretary of War Elihu Root. The bill was reported favorably by the Committee on Military Affairs and was passed by the Senate, but it failed in the House. [3] As events would have it, Mount Rainier National Park emerged as the first national park to be patrolled exclusively by rangers, without resort to troops. To contemporaries, however, the concept of a park ranger force was still so inchoate that calls for troops did not seem inappropriate. Indeed, another bill providing for a detail of troops to Mount Rainier National Park was introduced in 1910 and once again garnered the support of the Secretary of the Interior, though it too did not pass. [4]

Meanwhile, the new "forestry service" provided some nominal protection of Mount Rainier visitors and resources. The Forest Reserve Act of 1897 authorized the Secretary of the Interior to appoint forest supervisors and rangers to patrol the forest reserves. Under the new "forestry service," the Commissioner of the General Land Office appointed a forest supervisor to take up headquarters in a town near each forest, and the forest supervisor in turn hired rangers to patrol districts within the forest and enforce the regulations locally. [5] Beginning in 1898 or 1899, the forest supervisor of the Mount Rainier Forest Reserve detailed a single ranger to visit Paradise Park periodically and keep a watchful eye on campers. [6] This was the first instance of "visitor protection" in Mount Rainier, and must have been among the first such ranger assignments in the nation.

The call for a permanent ranger force in Mount Rainier National Park originated with the Allen family of Ashford, Washington. In the early 1890s, O.D. Allen, a Yale University botany professor, moved to the Pacific Northwest for the benefit of his health, and established a homestead about two miles east of Kernahan's Ranch (Ashford). Over the next ten years, Allen and his sons, Edward and Grenville, made innumerable botanical expeditions to Mount Rainier, producing the first notable scientific collection of Mount Rainier's flora. [7] By the 1900s, the Allen sons possessed what Edward described as "an intimate personal knowledge of all the southern slopes of Mt. Rainier." Though Edward Allen had been in every state west of the Mississippi, nowhere else had he "seen a region so beautiful and more unique." [8] In 1903, Edward and Grenville Allen assumed two of the most influential forestry positions in the region, Grenville as supervisor of the Mount Rainier Forest Reserve and Edward as the General Land Office's forest inspector. Grenville had investigated the unauthorized charging of a toll on the trail to Paradise Park the previous year when he was a forest ranger, and both men recognized the need for more rangers to patrol the national park. [9]

In March 1903, Forest Inspector Edward Allen made a report to the Secretary of the Interior urging that the recent appropriation by Congress for improving the park should be used for protection as well as road development. Allen's report was the first official overview of the resources of the new national park. It reiterated Bailey Willis's conception of the park as an arctic island in a temperate zone. "The extent of this truly high mountain territory has preserved conditions such as were widespread immediately after the ice age more perfectly than has any other region in the United States," the report stated, "and there still exist many species of Arctic fauna and flora extinct elsewhere except in the inaccessible North." Forest Inspector Allen recommended specifically that at least two forest rangers be assigned to the park, one in the Paradise-Longmire vicinity and the other in the Spray Park-Carbon River area, "to perform fire and game protection work from July 1 to the coming of heavy snow, usually in November." [10] The Secretary of the Interior concurred with this recommendation and authorized Forest Supervisor Grenville Allen to assume charge of Mount Rainier National Park and assign two men to the northern and southern sections of the park beginning that season. [11] This marked the real beginning of ranger protection in Mount Rainier National Park. It is notable that one Allen son recommended it while another saw to its implementation, and that both men were officials of the new forestry service (now the U.S. Forest Service).

Grenville Alien

Grenville Allen served as acting superintendent of Mount Rainier National Park from 1903 to 1910 and was responsible for founding the ranger force. He appears to have had in mind from the outset that this ranger force would be made up of trustworthy, self-motivated, professional men. The qualities he looked for in these rangers were firmness, discretion, business ability, and of course, woodcraft skills. It is not known how Allen recruited his rangers, but in some cases he secured their service year after year. Still, as he pointed out to his superiors, the seasonality of the work made it difficult to get competent men. In 1908, with the opening of the park to automobiles and the resulting increase in park revenues, he urged that some of the ranger positions be made permanent. "The organization of an efficient ranger force requires the permanent employment of men who can be depended upon to be thoroughly devoted to their occupation," he wrote. "On the whole, it seems to me that most of the rangers in the park should be employed throughout the year, and I believe that their exertions during the summer would compensate for the periods of enforced idleness during the winter." [12] The following year, the first two permanent ranger positions were created at Mount Rainier National Park.

Two years into Allen's acting superintendency, the young forestry service was transferred from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture. Formerly a division of the General Land Office, the forestry service now became a separate bureau, the U.S. Forest Service, under Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot. Pinchot laid a strong emphasis on professionalism, esprit de corps, and decentralization of authority. These initiatives influenced the development of Mount Rainier's ranger force. They not only influenced Allen's recommendations to the Secretary of the Interior to create permanent ranger positions, but probably inspired his suggestion of a uniform for park rangers and his push to construct ranger cabins in the park. [13] Mirroring the pattern of administration on forest reserves (renamed national forests in 1907), Allen divided the national park into ranger districts, putting each ranger in charge of a specified area. Allen also showed a preference for local men. His first two recruits, William McCullough and Alfred B. Conrad, were from Ashford and Eatonville respectively. [14] Whether his decision to recruit local men was merely expedient or deliberately in keeping with Forest Service policy is not known.

The rangers performed virtually all of the field work involved in administering the park. Their primary function was patrol. By patrolling the more frequently visited areas of the park, rangers were able to suppress poaching and the more brazen acts of vandalism, such as the cutting of green timber to construct temporary shelters or the making of bonfires using whole trees. Regular patrol also aided in the suppression of forest fires, and enabled the rangers to keep track of prospectors and grazers either inside or bordering on the park boundary. (These activities are discussed in more detail in Chapter VI on protection of resources.)

In the few weeks at either end of the tourist season when weather permitted, the rangers turned to road and trail repairs and new trail construction. The principal aim of trail development was to facilitate patrol and thereby improve the protection of park resources. A secondary aim was to open new areas of the park to backcountry users, although this was not without risk, as Allen explained in his annual report for 1904:

A very small portion of the area included in the national park is frequented by tourists. This portion is, however, peculiarly attractive, and is extensive enough for the needs of all who are likely to enter the park for many years. The mountainous and broken nature of the country, its high altitude, and the absence of trails, prevent the other parts of the park from being frequented by tourists. These conditions are a natural protection to the park. It would not be advisable to extend a system of trails into the remoter parts of the reserve unless the force of rangers was at the same time so increased as to enable such patrol to be maintained as would protect the region thus opened from forest fires and the destruction of game. [15]

During Allen's superintendency, trail development was limited to the north and south sides of the park. Rangers rerouted and improved the trail to Indian Henry's Hunting Ground, extended the Carbon River trail over to the White River, and improved the trails to Crater (Mowich) Lake and Spray Park. There were existing hunters' trails on the west and east sides, but these remained unimproved. Visitors made what would today be called a "social trail" from Paradise Valley past Sluiskin Falls to the Cowlitz Glacier. [16] It was probably a good indication of Allen's administrative priorities that the first two trails built primarily for their scenic value to tourists were completed after Superintendent Edward Hall took charge in 1910. These were the trails to Eagle Peak and Rampart Ridge, both commencing at Longmire Springs. [17]

As dedicated as Allen was to the protection of the national park, his responsibilities as supervisor of the Rainier National Forest seriously divided his time. Two of his biggest concerns, fire suppression on the drier eastern slope of the Cascades and management of grazing permits on the national forest, largely drew his attention away from the park. In 1906, the Secretary of the Interior tried to enter an agreement with the Department of Agriculture whereby a portion of Allen's salary would be paid from the Mount Rainier National Park budget, but an 1885 law prevented this. Instead, Allen continued to draw his entire salary from the Forest Service while serving as acting superintendent for the national park. Local organizations such as The Mountaineers protested this arrangement, and in 1910 Congress finally approved the Department's request for an appropriation to cover a superintendent's salary as well as the salaries of a force of rangers. [18]

This was no panacea for improving the administration of the park, however. Until the creation of the National Park Service, national park superintendents were customarily selected according to the spoils system. This meant that the political party which controlled the executive branch of government used these salaried positions to reward the party faithful, giving little consideration to job qualifications. From 1910 to 1916, Mount Rainier National Park had four superintendents (called supervisors from 1914 to 1916, after Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane appointed a general superintendent for all the national parks), and only the last in the series had appropriate training. Edward S. Hall, a Republican Party stalwart who served from January 1910 to July 1913, capably guided the park administration through the early years of expanding visitor use and concessions development, but his reputation finally suffered due to some questionable dealings with a timber sale contractor who operated inside the park (see Chapter VI). In the summer of 1913, after the Democratic Party captured the White House for the first time in sixteen years, Hall was among more than half a dozen national park superintendents who found himself without a job. He was replaced by a loyal Democrat, Ethan Allen (no relation to Grenville Allen), who resigned after eighteen months and was succeeded by another political appointee, John J. Sheehan, in January 1915. When Stephen Mather met Sheehan at the third National Parks Conference that spring he was singularly unimpressed, and afterwards had him removed from office. [19] Sheehan's removal touched off another scramble for political patronage. This caused some disgust among the friends of the national park in Washington state who were following the matter and thought the national parks deserved more professional stewardship. [20] But the last pre-NPS superintendent was Mather's choice: DeWitt L. Reaburn, a USGS topographical engineer, with railroad-building experience in Alaska and South America and, according to Mather's biographer, "more of credit in his record than the bulk of the political superintendents combined." [21] Reaburn served for nearly four years and really belonged to the new era that began with the formation of the National Park Service.

Beginning in 1910, the superintendent maintained an office at the park entrance and a "gatekeeper" was duty-stationed in the same building to handle automobile permits and compile a record of everyone entering the park. Superintendent Hall started in 1910 with a ranger force of six men—two permanent and four seasonal, including the gatekeeper. The two permanent rangers were assigned to the north and south sides of the park respectively. This force fell to five in 1911 and 1912, rose to seven in 1913 and 1914, and reached nine in 1915. Superintendent Reaburn gave a full picture of the distribution of the ranger force in that year:

During the season there were employed in the park service nine park rangers: Thomas E. O'Farrell, chief park ranger, stationed on the Carbon River at the northwest corner of the park, from which point he directed the patrol, trail, and telephone construction work on the north side; Prof. J.B. Flett, park ranger, stationed at Longmire Springs in charge of traffic, camp grounds, and the distribution of park literature, general information concerning the flora, trees, shrubbery, etc.; Rudolph L. Rosso, park ranger, stationed at Paradise Valley, in charge of Paradise Valley and Indian Henry's Camps; Arthur White, temporary park ranger, stationed on White River in the northeast corner of the park; Herman B. Burnett, temporary park ranger, stationed at Ohanapecosh Hot Springs in the southeast corner of the park; Earl V. Clifford, temporary park ranger, stationed at the park entrance, in charge of registration of visitors and issuing automobile permits; Archibald Duncan, L.D. Boyle, and M.D. Gunston, temporary park rangers, stationed at Nisqually Glacier, Narada Falls, and Paradise Valley, respectively, as traffic officers, under the supervision of Chas. A. Clark, general foreman of road improvement work. [22]

It is worth noting that with the opening of the road for automobiles all the way to Paradise Park, fully one third of the ranger force was now assigned to traffic control. In a sense, this marked the coming of age of Mount Rainier National Park.

Building an Infrastructure

Still another duty performed by rangers in these early years was the construction of ranger cabins. Each ranger was given a "station" as well as a district to patrol; this was the site to which he normally returned at the end of his working day. Ranger stations preceded cabins, and rangers must have made do with mere tent accommodations at first. In 1913, for example, Superintendent Ethan Allen indicated that "the Indian Henry's Hunting Ground Station is in need of ranger quarters." [23] Understandably, rangers were eager to build cabins as soon as they could get authorization to do so. The first ranger cabin was built by the gatekeeper at the main park entrance in 1908, and by 1916 every ranger station in the park was furnished with a log or frame building. These ranger stations were distributed as follows: Nisqually Entrance, Longmire, Paradise Park, Indian Henry's Hunting Ground, Carbon River, White River, and Ohanapecosh (cabins), and Nisqually Glacier and Narada Falls (frame buildings) [24]

|

| The Oscar Brown cabin. The Interior Department 's chief clerk, Clement S. Ucker, recommended that this cabin serve as a model ranger cabin for other national parks. (Photo courtesy of Mount Rainier National Park.) |

The first cabin, known locally as the Oscar Brown cabin after the ranger who built it, is the only one from this era that still exists. [25] With the exception of the Oscar Brown cabin and the cabin at Longmire Springs, which both served as family residences, these cabins were simple, one-room structures, which apparently went up with little administrative oversight. [26] In the case of the Oscar Brown cabin, Acting Superintendent Grenville Allen provided Ranger Brown with a building plan, and Brown apparently built the cabin with Ranger McCullough's help in the early spring of 1908. Five years later, this cabin caught the eye of the Interior Department's chief clerk, Clement S. Ucker, who thought it was "an ideal cabin for the national park service." Ucker requested Superintendent Hall to send him a photograph of the cabin, a drawing of the floor plan, and its approximate cost. He then directed that the plan be redrawn by a draughtsman and distributed to the other park superintendents with the suggestion that it be adopted as a model ranger cabin. It is not known what became of this plan, though the requested photographs were in fact preserved in the department's files. [27]

The structure which absorbed the most official attention was the log archway over the main park entrance. Arguably, the archway represented the first effort to beautify Mount Rainier National Park with a structure of rustic design. (The Oscar Brown cabin was older, but officials showed little interest in its aesthetics until later.) The idea for the archway originated with Secretary of the Interior Ballinger, who visited the park in 1910 and found the entrance unattractive, with a dry riverbed on one side of the narrow road and jumbled rock on the other and nothing marking the boundary except the ranger's cabin and a painted signboard. At Ballinger's request, Superintendent Hall submitted a plan and cost estimate. Hall's idea was "to use the largest cedar logs obtainable for this work." It would consist of "two uprights on each side of the road with cross pieces to bind them together at the top and one or two heavy logs to run from the uprights across the road." [28] Ballinger approved $250 for labor and materials, stipulating that the plans should include "a gate of rustic design constructed of cedar poles. The gate to be of somewhat similar design to that at the entrance of the home of Superintendent Hall but larger." [29] The archway was erected in the spring of 1911. From the arch a three-foot diameter log, planed on two sides, was suspended by heavy chains with "MT. RAINIER NATIONAL PARK" chiselled into its face. [30]

Another innovation in this period was the introduction of telephone communications between ranger stations, road construction camps, and the superintendent's headquarters. The first telephone line in the park was built by the Tacoma and Eastern Railroad Company under a special use permit dated April 29, 1911. Park officials used this line to communicate between Longmire Springs and the park entrance. In 1913, the government constructed its own single-wire telephone line from the park entrance to Paradise Park, with intermediate stations at Kautz Creek, Longmire Springs, Nisqually Glacier, and Narada Falls, at a cost of $750. By connecting with Forest Service lines south of the park, communication between the park headquarters and the Ohanapecosh Ranger Station was also established. [31] In 1915, the line was extended over the west-side trail from Longmire Springs through Indian Henry's all the way to Carbon River, providing the first direct telephone link between the north and south sides of the park. [32] Later that summer, the department authorized a $900 expenditure for construction of a line from boundary post no.66 (White River Entrance) to Glacier Basin, linking the last ranger station at White River into the system. [33] This gave the park a total of ninety miles of government telephone line in addition to the six-mile Tacoma and Eastern telephone line from the park entrance to Longmire Springs. The system brought the whole ranger force into direct telephone communication with the superintendent's headquarters at Nisqually Entrance.

|

| The archway at the Nisqually entrance. Note the National Parks Highway sign on the left. (Photo courtesy of Mount Rainier National Park.) |

ROAD CONSTRUCTION

The people of Washington state generally agreed that the first need of Mount Rainier National Park was to get an adequate road built, presumably to Paradise Park. In August 1900, Washington's Representative Francis W. Cushman requested the U.S. Geological Survey to make a preliminary survey and cost estimate. The USGS report, completed that fall by Fred G. Plummer, suggested that a road from the southwest corner of the park to Paradise Park could be built for $90,000. In January 1901, Cushman forwarded this report to the Secretary of the Interior with the suggestion that the department request an appropriation in the next sundry civil appropriation bill. The Sundry Civil Act of March 3, 1903 included the following item:

Mount Rainier National Park: To enable the Secretary of War to cause a survey to be made of the most practicable route for a wagon road into said park, and toward the construction of said road after the survey herein provided for shall have been made, ten thousand dollars. [34]

This was the first appropriation made for Mount Rainier National Park.

The road to Paradise Park was surveyed in 1903 and built between 1904 and 1910, after which improvement work continued for another five years. This constituted the first of three main bursts of road building in the park's history, and the only one undertaken by the War Department. [35] Although the War Department would turn the road work over to Interior in 1912, the War Department had an important influence on the park's administration and development for the nine years it was present in the park.

Eugene Ricksecker

The War Department's legacy was enhanced by the dedicated service of Eugene Ricksecker, the assistant engineer who designed and supervised construction of the road and maintained a lively interest in all phases of the park's development until his death in 1911. [36] The department's chain of authority down to Ricksecker may be briefly described. Secretary of War William H. Taft assigned the initial task of surveying, and the subsequent task of road construction authorized by Congress in 1904, to the Army Corps of Engineers, under Chief of Engineers Alexander Mackenzie. Mackenzie, in turn, put the Corps' Seattle District Office in charge of the work. The Seattle District Office was headed by four different men in this nine-year span; these men were Eugene Ricksecker's direct superiors. Major John A. Millis headed the office from 1903 until the summer of 1905. He was followed briefly by Lieutenant F.A. Pope, then by Captain Hiram M. Chittenden beginning in the spring of 1906. Finally, Major Charles W. Kutz assumed charge of the Seattle District Office from Chittenden in 1908. For most of this period, Ricksecker had his main office in Tacoma and a field office at Longmire Springs. [37]

In the spring of 1903, Ricksecker canvassed local people on various existing routes into the park and easily settled on the Nisqually River Valley as the best alternative. He gave two reasons for this choice: it was the most popular among tourists owing to the fact that a road and trail already existed to Longmire Springs and Paradise Park, and it was the approach used most often by climbers, since it led to the easiest route of ascent of the mountain's summit. [38] Ricksecker then initiated the preliminary survey, beginning with actual topographical mapping of the area from the southwest corner of the park to the upper Nisqually River and entire Paradise Valley. He gave the head surveyor, Oscar A. Piper, instructions to take the road past two outstanding scenic attractions, the Nisqually Glacier terminus and Narada Falls, and as many other points of interest as possible. This was accomplished between July and November 1903. The route was 24.5 miles long. It included two additional points of interest: Christine Falls and a dramatic overlook of the Tatoosh Range from "Gap Point," later renamed Ricksecker Point in honor of the engineer. Rather than taking the direct route up Paradise Valley, as the trail did, it started climbing the 2,800 feet from Longmire Springs to Paradise Park by a series of "loops" or switchbacks on the flank of Rampart Ridge. [39]

Ricksecker emphasized that the road would be designed "solely as a pleasure road." A pleasure road was a rare specimen of engineering in that era, made all the more unusual by the mountain topography. The road would not only give access to the highcountry, but would harmonize with the landscape and itself give pleasure to the traveler. Writing about his general design for the road's curves, for example, Ricksecker explained:

The intention is to generally follow the graceful curves of the natural surface of the ground, as being most pleasing and far less distractive than the regular curves laid with mathematical precision. It is not proposed, however, to avoid all through cuts as this would in some instances introduce curves of entirely too short radii. The least radius permissable is fixed at 50 feet; the shortest aimed at is 75 feet. Curves of this radius will obtain only at a very limited number of places, principally at loops. Very few and quite short tangents will occur. The traveler will thus be kept in a keen state of expectancy as to the new pleasures held in store at the next turn. [40]

Ricksecker specified a generous width of clearing of sixty feet, or about fifteen feet on either side of the road, in the timbered sections, to ensure adequate exposure to sunshine so that the road surface would dry out after summer rainstorms and so that the snowpack would melt quickly in the spring. But to diminish the sense of barrenness and artificiality that this swath through heavy timber would create, a few large trees would be left standing. No unsightly borrow pits would be made, guardrails would be made of native rubble, and wherever possible drainage would be accomplished with ditches leading along the road to some natural stream rather than by introducing a large number of culverts. [41]

What stamped this as a scenic road above all was the gentle gradient, which added considerably to the road's length. The object was not to find the shortest practicable route between two terminals, Ricksecker stressed, but to make it a pleasing drive. With his emphasis on the joy of the road, one might presume that Ricksecker was thinking of the dawn of the automobile age, but he seems to have had motorless vehicles chiefly in mind. In justification of the road's light gradient, Ricksecker wrote:

Steep stretches where teams must walk soon become monotonous and pall upon the senses. Light grades offer no excuse for the teamster to walk his horses and insinuate "Here's a good place to walk." It is generally conceded, I believe, that about a 4% gradient is the steepest up which teams can trot; that they will walk almost as rapidly ascending an 8% gradient as a 4%; that the descent of grades steeper than 8% becomes rapidly more dangerous as the gradient increases. Grades steeper than 5% cannot be ascended with reasonable effort, by cycles. [42]

Although Ricksecker only lived to see the south side of the park developed (he died at age fifty-two), he had a vision that Mount Rainier National Park would one day have a very extensive system of roads. He thought that the many access routes known to local people should eventually be improved with roads, and that as many of these roads as possible should connect within the park. [43]He thought there should be a scenic road around the mountain, built as near the permanent snow line as possible in order to maximize the open vistas. "The diversified and changeable scenery to be obtained at a high elevation far outweighs a route at a lower elevation, passing through a forest that becomes more or less monotonous," he wrote. [44] In a burst of enthusiasm, he even suggested that the road to Paradise Park be extended to Camp Muir. [45]

Ricksecker's ideas contrasted with the next generation of park road engineers in the 1920s and 1930s, who were trained in landscape architecture and showed more sensitivity to the threat of overdevelopment and the scarring of the landscape that roads entailed. Perhaps it is unfair to judge Ricksecker's vision by the standards of a later era; given his keen sense of aesthetics, it is likely that he would have modified his views over the years. But is it worth considering the extent to which Ricksecker defined the park visitor's experience in relation to vehicles. The view from the road framed Ricksecker's whole sense of aesthetics. The next generation of park road engineers would take a broader perspective and consider, too, the visual impact of the road as seen from a distance. Ironically, due to the lay of the land, it was the main roads designed and built by this latter generation—the road to Sunrise, the Westside Road over Round Pass, the Stevens Canyon Road (begun in the 1930s but not completed until 1957)—that caused the worst visual scarring in the park. Consequently, Ricksecker's reputation for beauty engineering has held up very well over the years, while his original road alignment has scarcely been changed.

Ricksecker's record of administration of the road construction is a little less glowing. In the first place, his original cost estimate of $183,000 proved to be quite low. Congress appropriated $30,000 in 1904 with which to complete the survey and begin construction, and made additional allotments each year which saw the road to completion for a total cost of $240,000. However, Ricksecker had found it necessary almost at the start to reduce the width of the road from sixteen to twelve feet, and in places it narrowed to ten. Moreover, the road remained unsurfaced. According to an Interior Department inspector who investigated the road in 1911, it would cost an additional $325,000 to widen and macadamize the road according to Ricksecker's original specifications. [46]

Ricksecker also had difficulty getting the work started. Initially the government contracted the work to one A.N. Miller, whose company was to commence with the difficult four-mile stretch leading out of Longmire Springs. The work proved much more expensive than anticipated; disastrously, only one mile was completed during the whole 1905 construction season. Chief of Engineers Mackenzie annulled the contract and reassigned Captain Hiram Chittenden, builder of the Yellowstone road system, to the Seattle District to take the Mount Rainier road project in hand. Chittenden made three major changes to Ricksecker's plan. First, he insisted that reconstruction of the seven miles of existing road from the park entrance to Longmire Springs must precede the extension of the road to Paradise Park. (He informed Mackenzie, "The existing road built by private parties is, I think, without exception the worst I have ever traveled over.") Second, the per-mile cost of the road had to be sharply reduced. "I found upon visiting the work already done that it is of a very elaborate character, such as cannot possibly be carried over the entire line of road for many years to come," Chittenden reported. "The roadway is 25 feet wide and built with an elaborate system of berms and drains and other refinements of road construction that are more suitable to a city highway than to a road in this wild and rough country." Chittenden directed that the clearing be narrowed from sixty to thirty feet, and the roadway narrowed from sixteen to twelve. Third, opting to forego any more contracts, Chittenden put Ricksecker directly in charge of the work. This was "in modified form, the system under which work was done in the Yellowstone." [47]

In 1907, the road was completed from the park entrance to Longmire Springs, and for the first time automobiles were admitted into the park. In 1908, the road was opened to Nisqually Glacier—the first road in the United States, it was said, to reach a glacier. [48] In 1909, it was completed to within a few miles of Paradise Park, and in 1910 the last difficult stretch above Narada Falls was built. President Taft, who had been Secretary of War when the project was initiated, received the honor of being pulled to the top in a horse-drawn automobile in October 1911. A car reached Paradise Park under its own power in 1912, but the road was so narrow above Narada Falls that it was not opened to cars generally until 1915. [49]

Ricksecker spent nearly seven years supervising the construction of this impressive road—one of the earliest scenic mountain roads in the national park system. With his field office located at Longmire Springs, it is no exaggeration to say that from 1903 to 1910 he spent more time in the park than Acting Superintendent Allen. Ricksecker cared deeply about the park. He brought to Allen's attention the fact that Virinda Longmire was trying to secure a homestead patent and that Robert Longmire had opened a saloon in the park. [50] He recommended a boundary extension to Secretary of the Interior James R. Garfield in order to protect the park's wildlife, and he protested the sale of timber along the road in the southwest corner of the park. [51] He may have been the first to urge the development of a bridle trail around the mountain (the future Wonderland Trail), and the first to recommend that the government acquire the Longmire tract. He suggested that the government build climbers' shelters at Camp Muir and the summit crater. [52] At a time when the Department of the Interior had scant information on conditions in the park, Ricksecker was an important administrative presence.

Other Road Surveys

The Sundry Civil Appropriation Act of April 28, 1904 included $6,000 for a survey of a second wagon road into the park, beginning at the eastern boundary of the forest reserve. This small sum allowed only a very cursory survey to be made. It was accomplished that summer and fall by Junior Engineer John Zug of the Corps of Engineers. Zug traced a route up the Naches and American rivers to Bear Gap (just south of Chinook Pass), then along the main "ridge" between the Cascade Crest and Mount Rainier as far as Cowlitz Park. Zug found this "ridge" too broken to be a practical route. Moreover, Zug had hoped to complete the survey from Cowlitz Park around to Paradise Park, but decided there were too many intervening snowfields and canyons to continue. [53]

The cost estimates that accompanied the Zug survey were so arbitrary as to be useless, but Zug's report on the terrain did plant a few seeds. First, the report provided a clearer picture as to the practicability of punching a road over the Cascade Mountains via the Naches and American rivers. This was of singular interest to the people of Yakima. Second, Zug assumed that the eastside road would terminate at some alpine park, just as the southside road did. He chose Cowlitz Park; later planners would look again at this possibility, together with Ohanapecosh Park and Summerland, before finally settling on Yakima Park. Third, Zug doubted that a high-elevation road was possible around the southeast side of the mountain, and suggested that a road connecting the east and west sides would have to swing well south of the park boundary. Ricksecker took exception to this, arguing that the road should maintain all the elevation it gained between Longmire Springs and Paradise Park. [54] The Department of the Interior conducted two more road surveys on this side of the mountain in 1913 and 1916, the first more or less following Zug's suggested route south of the park, the second going by way of Reflection Lakes and Stevens Canyon to Ohanapecosh Hot Springs. [55] This debate between high-elevation and low-elevation routes in the southeast quadrant of the park would perplex park planners all the way up to the 1930s.

For some years, it was proposed to build a road to Indian Henry's Hunting Ground. The Corps of Engineers staked a route that started from the main park road near Christine Falls, went over Rampart Ridge, and traversed around the head of the Kautz Creek drainage within view of the snout of Kautz Glacier (once again, aiming for an eventual high-elevation road around the whole mountain). [56] In 1911, Interior Department Inspector Edward A. Keys tried to walk this route but found it too vaguely marked to follow. In any case, he recommended that the Indian Henry's Road not be undertaken for the time being, since the department would have enough to do widening and macadamizing the road to Paradise. [57] This was the last time the Indian Henry's Road was seriously considered.

Transfer of Jurisdiction for the Park Road

The War Department's mandate in the park was limited to road survey and construction. With the appointment of a park superintendent in 1910, and the completion of a serviceable road to Paradise, Interior Department officials began to negotiate with War Department officials for the transfer of jurisdiction of the park road. In 1910 and 1911, Superintendent Edward S. Hall used a portion of Interior's park appropriation for road repairs and in his annual report for 1911, Superintendent Hall recommended that the road "should be transferred from the War Department to the Interior Department, placed under the control of the park superintendent, and appropriations be made for its upkeep and repair." [58] That fall, Secretary of the Interior Ballinger dispatched Inspector Edward A. Keys to Mount Rainier to prepare appropriation estimates for the department.

In his report, Keys stressed that the Interior Department would be taking on a large project. "While the road has been put through," he cautioned, "the actual work of making a first-class macadam road is not much over half completed, and the cost of widening and macadamizing the present road is going to be expensive." [59] Keys made detailed estimates of the cost of widening and surfacing the road. These came to $160,915.19 and $164,076.00 respectively, for a total of $324,991.19. [60] Keys' report was too late to be included in the department's budget estimate for the coming fiscal year. But ten months later, in the fall of 1912, the Interior Department prepared to take over the road work. The Secretary of the Interior accepted a transfer of camp outfit, tools, and other equipment from the Corps of Engineers to the park superintendent. [61] And at the secretary's request, Superintendent Hall submitted a budget estimate of $343,400 for the next fiscal year. [62]

At this point the transfer of jurisdiction from War to Interior ran into a couple of snags. In the first place, the Interior Department unexpectedly slashed the park's budget estimate from $343,400 to $13,400. Investigating how this fiasco had occurred, the Seattle-Tacoma Rainier National Park Committee's lobbyist in Washington, D.C. learned that it was the handiwork of Assistant Secretary Samuel Adams, whom President Taft had directed to come up with $11,200,000 in cuts from the department's annual Book of Estimates five days before it had to be submitted to Congress. Though the Secretary of the Interior and the department's chief clerk were both familiar with Mount Rainier National Park and the uncompleted road, both had been away from the capital when the cuts were made. [63] Informed of this situation in February, President Taft sent the following letter to Secretary Fisher:

My Dear Mr. Secretary:

I wish you would at once prepare a supplementary estimate for the making of roads in the Mount Rainier National Park in Washington—$25,000 for the surveys and $150,000 for road construction. Send it to me and I will approve it and forward it to the Treasury Department.

I promised that this should be done when I was in Washington the last time. The proximity of this great National Park, with its beautiful mountain scenery, to two large cities like Tacoma and Seattle justifies an immediate expenditure for bringing the Park within the reach of the humblest citizen. It differs so widely from Yellowstone Park and the Yosemite in its accessibility if we only construct these roads, that I think immediate and generous action is fully justified.

The matter is under consideration by the Appropriations Committee now, and the estimate ought to be prepared at once.

Sincerely yours,

(signed) Wm. H. Taft. [64]

The estimate was duly prepared and submitted, belatedly, to the House Committee on Appropriations. But then a second obstacle arose. Congressman Stanton Warburton of Washington, trying to dramatize the national park's woes to his colleagues in the House, rashly introduced an amendment to the sundry civil appropriations bill which would transfer title for Mount Rainier National Park back to the state of Washington. His strategy backfired. He only succeeded in provoking the park's supporters back home. The Seattle-Tacoma Rainier National Park Committee sent a telegram informing members of Congress that Warburton's action did not represent the desires of the people of the state. Further, the committee got Governor Ernest Lister to go on record against the transfer of title. [65] Warburton's humiliation merely convinced the House to ignore the department's revised estimate for Mount Rainier National Park. As a result, the Corps of Engineers pulled out of the park and left road construction at a standstill. Even when the Interior Department resubmitted its estimate one year later, Congress saw fit to reduce the amount to $51,000. [66]

The second snag which prevented a smooth transfer of jurisdiction involved the muddle over the short section of road from the west boundary of the Rainier National Forest to the west boundary of Mount Rainier National Park. This three-mile stretch of road had been more or less "orphaned" by the fact that Pierce County would only improve the original Mountain Road as far as the national forest boundary, while the Interior Department would only maintain and repair the road beginning at the park entrance. Though Chittenden had directed Ricksecker to improve this section in 1908 (Ricksecker had wanted to make a completely new alignment, but the cost was prohibitive), the War Department's jurisdiction did not extend to maintenance. During the winters of 1910-11 and 1911-12, the road was practically ruined by the pounding it received from heavy trucks hauling away logs from the small timber sale operation being conducted in the southwest corner of the park. President Taft complained of the road's condition in October 1911, and by the following spring, dozens of Washington citizens were writing letters to their senators and congressmen protesting that the road was "like a hog mire," a "shame and disgrace," and "practically impassable." One citizen cabled Congressman Warburton, "Careless lumberjacks have ruined Mount Tacoma Road in forest reserve; vehicles sink in mire to hub... .We believe Government should fix it". [67] Bills were introduced in 1911 and 1912 to make a special appropriation for the War Department to repair this section of road, or alternatively, to transfer jurisdiction of the entire road (including this three-mile section through the national forest) to the Department of the Interior. Neither bill got out of committee. [68]

The three-mile section of road was nominally under the jurisdiction of the Rainier National Forest, but the Department of Agriculture would not authorize any expenditures for its upkeep. Further complicating the picture, the road passed through five forest homestead claims belonging to W.A. McCullough, O.D. Allen, A.A. Mesler, George Uhly, and Edward S. Hall. [69] The government's right-of-way through these claims had not been perfected. [70] When Congressman Warburton made a speech on the floor on behalf of his Mount Rainier road bill, there were objections that the federal government should not be maintaining a road that went through private property, or alternatively, that the Interior Department should not be given responsibility for a road through a national forest. [71]

For their part, Interior Department officials wanted the Forest Service to take care of it. When Thomas H. Martin of the Seattle-Tacoma Rainier National Park Committee broached this problem with officials at the National Parks Conference in Yosemite in 1912, he was encouraged to seek the cooperation of the Forest Service. The Forest Service proposed to distribute its available road maintenance funds among some twelve to fifteen projects in Washington state, including the three-mile section across the Rainier National Forest. But the Tacoma-Seattle Rainier National Park Committee protested that this would be a waste—"a few hundred dollars here and there would be absolutely no good." Instead, the committee negotiated an agreement between the Pierce County commissioners and the Forest Service. Both parties would contribute $12,700 toward repairs on the three-mile section of Mount Rainier road. [72]

These adjustments of jurisdiction over the government road paralleled the issue of federal and state jurisdiction in the park with regard to law enforcement. While the two problems were technically distinct and demanded separate resolutions, they played off one another in the public's mind. Nothing demonstrated the problem of muddled jurisdiction more forcefully for the park visitor than the controversy over this three-mile section of road. When this situation finally received the attention it deserved, it set the stage for Congress's long-delayed consideration of that other problem of jurisdiction, law enforcement.

THE PROBLEM OF LAW ENFORCEMENT

All federal reservations require some kind of division of jurisdiction between federal and state law enforcement officials. Today the national park system contains three forms of federal-state power-sharing; these are known as exclusive, concurrent, and proprietary jurisdiction. Although in recent times the direction has been toward concurrent jurisdiction (that is, overlapping federal and state policing authority) in Mount Rainier National Park the federal government has exclusive jurisdiction. This is a legacy of the early years of the national park system when exclusive jurisdiction appeared to be the only effective alternative. In order to understand why this was so, it is necessary to consider how the national park rangers' authority to make arrests evolved in this era. National park law enforcement involves a combination of jurisdiction and authority.

Origins of Law Enforcement Authority

The origins of the park ranger's law enforcement authority, like the origins of the ranger force itself, can be traced to the new forestry policy that the nation pursued in the 1890s. As the Secretary of the Interior moved to establish a "forestry service" under the Forest Reserve Act of 1897, it soon became apparent that the field agents in this service were seriously hampered by the fact that they did not have authority to arrest persons caught violating the law. Instead, this authority rested with U.S. marshals and the judicial branch of the federal government. Thus, when a forest ranger caught someone violating the law—cutting timber or grazing livestock without a permit, for example—he had to obtain an arrest warrant from a U.S. marshal before he could stop the illegal activity.

Secretary of the Interior Hitchcock raised this issue with the Justice Department in April 1899, inquiring whether Justice would suggest that U.S. marshals be asked to deputize forest supervisors and rangers. Attorney General John W. Griggs replied in part:

The statutes for the protection of these forest reserves seem singularly deficient in that they do not provide any efficient means for the arrest of persons violating the laws or the rules and regulations for the protection of these reservations. These laws, rules, and regulations afford little of the protection intended without some provision for the speedy arrest of persons violating them. The protection of these large territories is a difficult matter at best, and is substantially impossible without authority for the speedy arrest of persons committing depredations thereon or otherwise injuring them, for in most cases, and in the worst, before complaint could be made, a warrant obtained, and officer to serve it, the damage would be done and the offender beyond reach. [73]

Attorney General Griggs advised that the Interior Department could not expect the U.S. marshals to deputize its field agents, for the separation of powers under the Constitution prevented it. Rather, the solution was for Congress to enact a law that would give forest supervisors and rangers the authority to make arrests.

More than five years later, the Interior Department finally obtained this authority when Congress passed the following act:

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States Congress assembled, That all persons employed in the forest reserve or national park service of the United States shall have authority to make arrests for the violation of the laws and regulations relating to the forest reserves and national parks, and any person so arrested shall be taken before the nearest United States commissioner, within whose jurisdiction the reservation or national park is located, for trial; and upon sworn information by any competent person any United States commissioner in the proper jurisdiction shall issue process for the arrest of any person charged with the violation of said laws and regulations; but nothing herein contained shall be construed as preventing the arrest by any officer of the United States, without process, of any person taken in the act of violating said laws and regulations. [74]

Yet park officials still found that the public was skeptical about their authority to police the park. That summer, one Henry Beader of Tacoma was caught cutting down a green tree and throwing it on his campfire, but resisted arrest by a park ranger. The ranger went to the U.S. commissioner in Tacoma and identified the accused, bringing the sawed-off tree stump to the hearing for evidence, but the commissioner still refused to place the defendant under bond to appear in court. Relating this incident to the Secretary of the Interior, Acting Superintendent Allen expressed regret that "the validity of the Act of February 6, 1905, was questioned," but added, "the fact of the arrest will to some extent prevent similar offenses in the future." [75] Possibly this incident did instill greater respect for the park ranger's authority among campers, for no more cases of vandalism were reported.

More doubtful was the ranger's authority to enforce the prohibition against hunting in the park. The regulations prohibited the killing of game and the carrying of firearms without the prior permission of the acting superintendent, but Allen and his rangers found that they were unable to enforce this ban in the courts. The situation was made more difficult by the fact that many miners entered the park to work their claims, which were legal under Section 5 of the Mount Rainier Park Act. The question arose whether these people could be forceably removed from the park for trespass when they were caught in possession of firearms. Assistant Secretary Frank Pierce advised Allen that until Congress accepted the exclusive jurisdiction over Mount Rainier National Park, or enacted a law providing for punishments for the killing of game in the park, rangers should only report violations of the game laws of the state of Washington. [76] In response to a further request for clarification from Allen, the assistant secretary detailed the ranger's police powers. The letter is worth quoting at length because it presents a clear picture of the constraints under which rangers operated:

Trespassers upon the park lands should be removed as soon as discovered, using only such violence for that purpose as may be necessary with an admonition not to repeat the offense. Tourists and other persons in the park who properly observe the regulations of the reservation are to be received at all times and treated with courtesy.

You are not authorized to either imprison persons or give them any sustenance at the Government's expense, nor will it be advisable for you to seize horses or other property for the purposes of confiscation...

You will take up all firearms found in the possession of any person or persons within the metes and bounds of the park, unless they have a permit from you authorizing the carrying of the same. This instruction applies not only to the Government lands but the lands covered by the patent to Longmire. Firearms taken up should be returned to the owners upon application at the end of the season.

As to authority to search wagons, carriages, and other vehicles and packs for firearms and game, and to enter patented lands for the purpose of taking up firearms...in cases where you have well-founded suspicions that firearms have been brought into the park in violation of the regulations, or that game has been killed in the reservation, you can make the desired search and also enter upon the patented lands in a peaceable manner for the purpose of determining the existence of firearms there, by whom they were brought in and by whose authority. Where game has been found which has been killed in violation of the laws of the State of Washington, the matter should at once be reported to the proper authorities, with a view to the institution of proceedings under the State laws....

It is not to be understood, however, that the regulations governing the park are to be enforced in a harsh or arbitrary manner or so construed as to work a hardship or loss of property, where an effort has been made to reasonably comply with the terms thereof; all persons entering the park, and especially those owning patented lands or who have valid mineral entries in the park, should be handled in a tactful manner in order that their cooperation in the management of the park may be secured, rather than their enmity....

During the summer months, no doubt, parties will be found bringing sheep, cattle, horses, and other stock upon the Government or park lands for purposes of grazing; in such cases it will be your duty to advise the persons in charge of the animals that they are trespassing upon the park lands and require them to immediately depart with their stock from the reservation; upon failure on their part to do so, after this warning, they should at once be ejected, with such force, as in your judgment the circumstances surrounding the case may require. While acting, however, with firmness, seeing that your orders for their departure from the park are being complied with, discretion and good judgment should be exercised to the end that neither bodily harm nor bloodshed may possibly ensue. [77]

This letter seemed to settle the matter as far as Acting Superintendent Allen was concerned. But until the federal government accepted exclusive jurisdiction over the national park, rangers had difficulty enforcing the park's rules and regulations in the courts. What was needed was a means of holding court expeditiously in the park so that poachers and trespassers would more likely be convicted.

Exclusive Jurisdiction Obtained

The Mount Rainier Park Act authorized the Secretary of the Interior to prescribe rules and regulations for its care and management; thus it placed the park under the secretary's jurisdiction. But Congress did not have the power to terminate the state's jurisdiction; this the state of Washington had to do. On the assumption that dual federal and state jurisdiction undermined the federal authority, Secretary Hitchcock refused to promulgate rules and regulations for the national park until the state ceded its part in the dual jurisdiction. [78] In March 1901, the legislature and governor of the state of Washington enacted such a law, provided that the cession was to take effect only when the federal government notified the governor that the U.S. was assuming "police or military jurisdiction" over the park. [79] With Congress not yet having made an appropriation for the administration of Mount Rainier National Park, Secretary Hitchcock held that it was impossible to accept the state's cession on those terms, and he did not push the matter. Thus the state's offer of cession was left standing. [80]

Nearly a decade later, in December 1910, Washington's Senator Piles introduced a bill to accept exclusive federal jurisdiction according to the state's terms. Representative Humphrey of Washington introduced the same bill in the House. It is unclear what caused this long delay; in the intervening decade, other national parks had been created and the federal government had moved expeditiously to establish exclusive jurisdiction over them. In any case, this bill still faced a difficult road. The Department of the Interior offered a number of strengthening amendments, aimed principally at making the bill conform to an Act of May 7, 1894, titled "Act to Protect the Birds and Animals in Yellowstone National Park," which had set that park up as a part of the U.S. judicial district of Wyoming and provided a list of punishments for various offenses. [81] Though both this Mount Rainier bill and another, introduced in the next Congress, died in committee, the department's amendments were incorporated into a similar bill for Glacier National Park in Montana, which was passed on August 22, 1914. [82] This act then formed the model for the Mount Rainier bill, introduced by Washington's Senator Wesley L. Jones on January 25, 1916. After minimal debate, Congress finally passed this bill on June 23, 1916. [83]

The principal features of this act were its detailed schedule of misdemeanor offenses, all of which were punishable by a maximum $500 fine and six-month prison sentence, and its directive to the U.S. District Court for western Washington to appoint a commissioner who would reside in the park and hold trial for any case involving violations of the park laws, rules, and regulations. [84]

LAND ISSUES

With the creation of Mount Rainier National Park, the Secretary of the Interior had jurisdiction over a large area of unsurveyed, poorly mapped terrain. Certain routine matters of land management had to be accomplished, beginning with the relinquishment of all Northern Pacific land grant holdings within the park as prescribed in Sections 3 and 4 of the Mount Rainier Park Act. The park boundaries needed to be surveyed, and the rugged topography needed to be mapped.

The Northern Pacific Land Grant

Sections 3 and 4 of the Mount Rainier Park Act described a two-step process: the Northern Pacific Railway Company would relinquish all of its grant lands in the park and the forest reserve to the United States, and then it would select an equivalent amount of lieu lands elsewhere. Public criticism of this overly generous deal, instead of abating with the passage of time, slowly mounted as the process of selecting lieu lands progressed. Although the act's sting landed elsewhere, particularly in the state of Oregon where the company took most of its lieu selections, the land exchange was not without significance to Mount Rainier National Park. [85]

The public's ire gave rise to many inaccuracies concerning the passage of the Mount Rainier Park Act and the land exchange. A congressman once said that the Northern Pacific unloaded 450,000 acres of worthless lands within three days after the Mount Rainier Park Act was signed. [86] This was part of the legend of the federal government's shady deal. In fact, the relinquishment was held up for several months by the Central Trust Company of New York (the trustee of the Northern Pacific Railroad Company's general first mortgage), who demanded payment from the Northern Pacific for the estimated value of the land before it would lift its mortgage on the land. [87] Another congressman later claimed that the Northern Pacific had exchanged "barren lands" for timber lands worth $10 million. [88] This was inaccurate, too, for a large proportion of the relinquished lands in the national park and forest reserve were heavily timbered, and the timber value of the lieu lands did not approach $10 million. Washington's Governor Marion E. Hay lambasted the Northern Pacific for selecting lieu lands that were unsurveyed, and therefore untaxed. [89] Pacific Northwest politicians scored easy points by attacking the Northern Pacific's land grant.

In response to this public criticism, the Secretary of the Interior made a modest adjustment of the Northern Pacific's claim in 1912. The secretary ruled that all odd-numbered sections in the park that were covered by glaciers could not be claimed by the Northern Pacific for the basis of lieu selections. [90] The ruling was based primarily on the Supreme Court case of Bardon v. Northern Pacific Railroad Company, which held that "public land" was only that land that the government intended to make available for public sale. Glacier-covered land would never be sold. Since the railroad grant embraced alternate square miles of non-mineral, public lands within a specified distance of the railroad, the glacier-covered land in Mount Rainier National Park had never been a part of the railroad grant. This ruling pruned 17,318 acres from the Northern Pacific's 454,458.52-acre relinquishment, but it hardly assuaged the public's bitterness.

Ironically, two small boundary extensions in the northwest and southwest corners of Mount Rainier National Park in 1926 would make the Northern Pacific Railway Company an inholder once again. These small inholdings should not be confused, however, with the Northern Pacific's original relinquishment of grant lands in 1899. The significance of the Northern Pacific's land grant was that it left a bitter legacy; the land exchange did not impinge directly on the administration of the park, but it created an animus in the public's mind toward the Northern Pacific's early involvement with the national park.

Boundary Survey

Section 1 of the Mount Rainier National Park Act defined the boundary of the park by township and range. None of the townships covered by the park had yet been surveyed, and the precise location of the park boundary was therefore not known. The boundary needed to be marked so that field agents of the Department of the Interior would be able to protect the park against trespassers, and so that the Secretary of the Interior could verify that the boundary was reasonable. (There was some concern that the western boundary of the park was too high up on the flank of the mountain and did not take in all of the Puyallup and Tahoma glaciers.)

The business of surveying township lines belonged to the General Land Office (GLO). The GLO usually contracted with private parties for township surveys, and in mountainous regions it was not unusual to find a series of surveyors abandon their contract before the work was finally accomplished. So it was with the townships overlapping the boundary of Mount Rainier National Park. On March 3, 1900, the GLO contracted for the survey of the exterior boundaries and subdivisions of two townships, covering the south and west boundary of the park. But the contractor failed to execute the survey and the GLO commissioner cancelled the contract. On January 23, 1903, the GLO awarded this contract to two other surveyors, and at the request of the Secretary of the Interior, the U.S. surveyor general in Olympia, Washington directed his examiner of surveys, M.P. McCoy, to follow up this work with a survey of the entire park boundary. But owing to delays in the execution of the township surveys, Acting Commissioner J.H. Fimple redirected McCoy in the fall not to attempt the boundary survey. [91]

The entire park boundary was finally surveyed by W.H. Thorn in the fall of 1908. By then, the western boundary had been established by township surveys, but the eastern boundary (which then ran down the middle of Townships 15, 16, and 17 North, Range 7 East) was definitely located for the first time. As a result, the Secretary of the Interior learned that the eastern boundary of the park fell considerably short of the crest of the Cascades and awkwardly intersected the White River a number of times. [92] (The eastern boundary would be extended to the Cascade Crest in 1931, and modified slightly in 1988.)

The boundary survey aided in the protection of the park. The boundary was a deterrent against trespass by poachers and graziers. Two years after the 1908 boundary survey, the Department erected a wire fence along the western boundary north and south of the park entrance to prevent loose stock from ranging into the park. It was another example of Mount Rainier National Park's pioneer beginnings that the first nine years of park administration were accomplished in the absence of a surveyed boundary. [93]

Topographical Survey

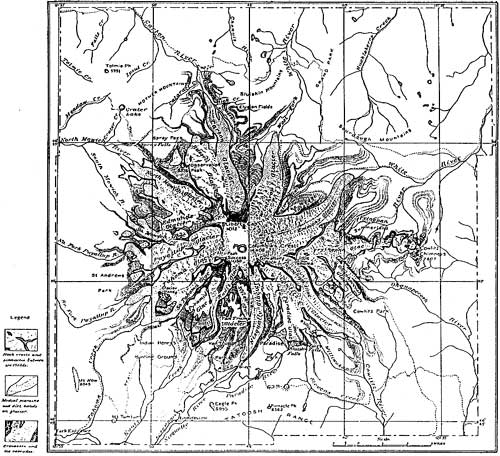

Next to having the boundary surveyed, park officials were eager to have a topographical survey of the park accomplished as well. Not the least important objective of a topographical survey was to establish the precise elevation of Mount Rainier, which was generally assumed to be the highest point in the United States outside Alaska. This task fell to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). In 1911, the USGS began a topographical survey of the park. Surveyors mapped the park on the ground, using a plane table on a tripod and an alidade (a special surveyor's tool which combined a telescope, level, and vertical arc in one device). The elevation of Mount Rainier was first ascertained by means of triangulation from various lower Cascade peaks. The broken-topped configuration of Mount Rainier's summit made this work especially difficult, however, and it was not until August 20, 1913 that the summit platform was mapped and the elevation of Columbia Crest was determined to be 14,408 feet above sea level (later adjusted to 14,410 feet, and more recently to 14,411 feet). The man who in 1913 accomplished this work had the improbable name of Colonel Claude H. Birdseye. [94]

|

| Map of Mount Rainier National Park, 1914 |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 24-Jul-2000