|

Navajo

A Place and Its People An Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER IV:

"LAND-BOUND:" 1938-1962

Between the end of the 1930s and the early 1960s, the pace of change on the western part of the Navajo reservation began to accelerate. More and more of the accouterments of the outside world were available, and with the exception of the war years, the steady stream of visitors increased. Roads began to traverse the region, and both the monument and the people around it began to experience more of the outside world than they ever had before. The isolation that previously characterized the monument diminished, and the modern world intruded on it in many ways.

As the pace of life on the western Navajo Reservation quickened, a growing sense that the monument was more than surrounded became common among its superintendents. Both in the regional office and at the park, NPS personnel realized that the location and lack of space at the monument constricted their ability to manage and protect it. Park managers felt increasingly "land-bound," in the words of long-time superintendent Art White, hampered by the non-contiguous nature of the monument and its dependence on the surrounding Navajo people. As development reached northeastern Arizona, the NPS at Navajo was forced to respond in a reactive manner.

The NPS response was gradual, limited by funding and the historically low priority of the monument in the park system. A slow alleviation of the lack of accessibility began the process of bringing Navajo National Monument to the attention of the public. Post-war road building programs brought automobiles within easy reach of the monument, forcing park managers to address the problems engendered by rising levels of travel throughout the Southwest. Yet the limitations on staffing and programming remained, and superintendents felt the pressure of being asked to do more with less. Area Navajos became an increasingly important asset for the monument as the area developed.

Yet the actions of the Park Service were responses to situations rather than proactive measures. By the middle of the 1950s, superintendents and regional office officials recognized the need for preparation for the coming changes in northeastern Arizona. Little notice of this need followed at the national level, even after the beginning of MISSION 66, the system-wide capital improvement program inaugurated in 1956. As a result, the planned and executed developments at Navajo lagged behind the need for facilities, creating a situation typical in the park system prior to the 1930s: NPS developments responded to immediate needs and did not lay the basis for long-term planning.

The arrival of James W. and Sallie Brewer late in 1938 began a new era at Navajo National Monument. Trained by Frank Pinkley and previously posted to Aztec Ruins National Monument in New Mexico, the Brewers were the first NPS professionals to manage Navajo. John Wetherill had served in his day; he guided the few hardy archeologists and travelers to the ruins. But the needs of the late 1930s were more comprehensive, and the Brewers brought Pinkley's training and philosophy to the last of the volunteer-run southwestern monuments.

The conditions they found were primitive. When they came, the only structure at Betatakin was Milton Wetherill's boarded tent, stocked with provisions he had left. Wetherill had been the only person to spend a winter in the canyon. The Brewers quickly decided that they could not follow Milton Wetherill's lead and passed their first winter in one of the large stone hogans at Shonto Trading Post the first winter. They cooked in a tent, for Harry Rorick did not permit cooking in the hogans. When the trail to the monument was free of snow, Jimmie Brewer frequently made the ten-mile trip in an old beat-up pickup truck. But heavy snows closed the trail in January and February, and the middle of March arrived before Brewer could make his way back.

By the middle of April, the Brewers settled at the monument. The first headquarters was a tent by Tsegi Point. Water came in a 55-gallon drum from Shonto. When it did not suffice, they went to a nearby seep discovered by Navajo mules. A horse named Messenger, left to the Brewers by John Wetherill, provided the primary means of transportation. Many evenings when the 55-gallon barrel was empty, Sallie Brewer rode Messenger to the seep for more water. Laundry posed another problem. Sallie Brewer later reported that at Navajo she "learned to wash clothes in strained, reheated dishwater." [1]

Part of the lure of the position had been the promise of a new residence, to be built the first year the Brewers were at Navajo. The tent was near the site of the proposed residence. Indian CCC labor built a two-room cabin in 1939, the same year they drilled a well, the first CCC work since the CWA project in 1933-34. The one-bedroom house was "beautiful," according to Sallie Brewer, who fondly recalled moving into it, but the complicated canyon sump-vertical pipe hole-rim pump-storage tank water system did not begin to function for another year. [2]

|

| The new custodian's residence built in 1939 was the first permanent housing at Navajo. |

A characteristic pattern of development began, albeit much later than at most park areas. As occurred elsewhere in the Southwest and across the nation, the installation of a professional Park Service person was only the first step in a plan of development. It was followed with a residence, and in many instances an administrative building, museum, or visitor center. But by the time the residence was constructed at Navajo in 1939, most of the rest of the park system had already been developed. During the 1920s, the major national parks constructed many of their amenities; most other areas were developed in the capital-program oriented phases early in the New Deal. By 1939, there were few park areas for which the NPS had plans that did not already have some kind of large-scale program underway. Despite the construction, Navajo remained at the far end of the world of the Park Service.

|

| There were so few buildings at Navajo that the custodian had to have his office in the living room! |

Ecological problems as a result of human use were a constant issue at the monument. Erosion, the prehistoric threat to populations in Tsegi Canyon, had made a dramatic reappearance since the end of the nineteenth century. In the thirteenth century, it helped drive the Kayenta Anasazi out of the region. In the twentieth century, overgrazing in the region was the cause. In the spring and summer of 1934, erosion had become a serious problem at the monument. Much of the shrubbery was dead or dying, and grass that had previously been ample had become scarce. [3]

By the middle of the 1930s, NPS officials began to search out remedies for the problem. Fencing seemed a good alternative, but Navajos from the area objected and threatened to cut the fence every night. Fencing had a different cultural connotation to the Navajo, particularly as the sheep reduction programs of the BIA gathered momentum. But the problem was real. Chief Engineer Frank A. Kittredge noted that the flat valley in front of Keet Seel had eroded to a depth of more than seventy feet for a three-mile stretch over the previous fifty years. He suggested a series of check dams as a response that would promote the natural rebuilding of the arroyo floor. [4]

Another proposal later in the decade involved an attempt to use nature to rectify the problem. In 1939, Regional Office Wildlife Technician W. B. McDougall concluded that the introduction of beavers into Betatakin and Keet Seel canyons might check erosion. The plans to add a new species to the region proceeded until Regional Director Hillory A. Tolson suspended them, pointing out that no proof of beavers living in the canyons during historic or prehistoric times existed and such an introduction of exotics was against NPS policy. Erosion continued as a primary threat to the condition of the ruins of the Tsegi Canyon area. [5]

By 1940, conditions for the staff at Navajo had begun to improve. Brewer marked the road to the monument on both sides of the trading post, and despite occasions on which the signs disappeared--presumably as firewood for Navajos in the vicinity--the trail was clearly marked. Using his pick-up, Brewer dragged the final ten miles from Shonto to the monument, keeping it in fine condition in good weather. Rain or melting snow turned the road to soup, for it had no drainage system. Travel became nearly impossible. The limitations of the budget made much of his effort cosmetic. Visitors and Park Service inspectors complimented Brewer on the condition in which he kept his monument, but development of the monument required greater support from the Park Service. [6]

In 1940, Navajo remained the most isolated monument with permanent personnel in the Southwest. Yet for a generation of park managers from Brewer to Art White, this quality became a major attraction. In the isolation, they could live a life apart from the noise and aggravation of the urbanized world. A position at Navajo gave them the ability to pursue interests in fields like anthropology and ethnology and to live near and among native people only marginally exposed to the modern world. For a certain kind of person, the custodian or superintendent position at Navajo National Monument held great attraction.

The location of the residence did little to improve the service visitors received at the monument. The cabin overlooked Betatakin Canyon, a position from which the custodian could see anyone who came up the trail from Shonto. Rumor suggested that the cabin was on Navajo land, but Brewer made a point of asserting the claim of the Park Service. But the descent to the ruins began at Tsegi Point, about a mile and one half farther to the west on the rim across a Navajo allotment. The rim of that side of the canyon was out of NPS jurisdiction. Visitors who made the trip found that they had to backtrack to reach first the headquarters cabin and then the trailhead. In Frank Pinkley's domain, this sort of situation was extremely rare. Pinkley built the southwestern monuments by accommodating visitors. This inopportune location was uncharacteristic of the Park Service. It showed how the management of Navajo National Monument differed from myriad other park areas.

As it did throughout the park system and the nation, the Second World War interrupted life at the monument. At the end of the New Deal, it seemed that Navajo would finally derive some benefit from the system-wide capital improvements of the decade. But the change in national emphasis that followed the attack on Pearl Harbor curtailed the development of facilities. Shortages of rubber limited vacation travel, and archeological exploration seemed unimportant in comparison to the war effort. Visitation diminished and nearly disappeared. From a high of 566 in 1941, visitation declined to a low of 45 in 1943. During all of July 1942, Brewer reported only one visitor. He told Byron L. Cummings he planned to "put up a sign on the Kayenta road offering a set of dishes to all visitors." [7]

The only visible improvement at the monument during the war was the addition of a fence up the canyon from Betatakin ruin that made the area "impervious" to Navajo stock. James Brewer left the monument to join the Seabees. William Wilson, a ranger from Wupatki who had also run the Rainbow Bridge lodge, served as his temporary replacement. Wilson doubled as the custodian of Saguaro National Monument near Tucson as well. He spent the winter of 1944-45 at Saguaro, leaving Bob Black, a local Navajo and the owner of the land adjacent to the Betatakin section, in charge of the ruin. The war accentuated the isolated character of the monument. [8]

The era following the Second World War saw the greatest increase in visitation in the history of the national park system. After four years of war, rationing, and a lack of consumer goods and vacation time, Americans had plenty of cash. Pent-up consumer demand permeated American society, including travel and leisure. With money they saved during the war and in the new automobiles for which they paid outrageous prices afterwards, Americans wanted to see their land--particularly their national parks. The construction of highways like Route 66, also the subject of a popular song, facilitated travel. At a time when Americans could travel from coast to coast by car, popular culture encouraged the experience. Gallivanting around in an automobile had become the American way; in the postwar era, many more people could enjoy the opportunity to travel by car. Trains ceased to be a primary mode of transportation for park visitors; by the 1950s, more than ninety-eight percent arrived in private automobiles. [9]

The impact of most of the increase in travel bypassed Navajo National Monument. At the end of a dirt trail, the monument remained remote from most travelers. Paved roads had not yet traversed the western Navajo reservation, and the visitors who came to places like the Grand Canyon to the southwest or Bryce Canyon and Zion national parks to the northwest could still not reach Navajo without great individual effort. Only those with a special interest in prehistory made the long and arduous journey past Shonto Trading Post to the little cabin atop Betatakin Canyon.

For a park without measurable resources, distance from civilization proved an advantage. As it had since 1909, the remote location of the monument precluded the kinds of management problems that prompted calls to close the national parks. Visitors inundated the national park areas they could reach, leaving trash and debris, damaging resources, and swamping park staff and facilities. Popularity was what the Park Service wanted, but too much of it drained the system. At Navajo, park officials did not need to worry. Even though the first motor coach to reach the monument stopped only two miles from the monument and visitation increased from the artificially low totals accumulated during the war to 705 in 1946-47 and 2,303 in 1956, the numbers were not sufficient to alter the routine to which Brewer and his seasonal Navajo staff were accustomed. [10]

As a result, Navajo remained a park out of time. While the park system faced rapid changes, the monument continued as a relic from an earlier era. Its superintendents could be snowed in or out by bad weather; a dirt approach road could become impassable for a range of reasons. The problems at Navajo dated from a simpler time, before visitation overwhelmed facilities and managers. Hard to reach, ignored by the hierarchy of the agency, and lacking most of the amenities common in the park system, Navajo was clearly apart from the mainstream of the Park Service.

Although custodians and superintendents selected themselves for the monument, they sometimes found their position depressing. The annual reports filed by Brewer and his successor, John Aubuchon, were terse, one-page documents devoid of any real information. Despite admonitions from the regional office, the reports remained perfunctory exercises. In 1949, Brewer offered an explanation: "Please be advised that no material is being furnished from this area because nothing of national importance has occurred." [11]

Brewer and his successors rightly felt that they served in an outpost far from the concerns of their agency. Their actions had great impact on the people around them, but little on the park system. Nor did their problems mirror those of the rest of the national parks. They could not marshal the kind of influence necessary to acquire the resources to implement programs, protect resources, and interpret Anasazi and Navajo culture. Despite a 1948 upgrade in the only position from custodian to superintendent, the people who worked there grew frustrated. Navajo was a hardship post by any measure of the term, and after Brewer left in 1950, Aubuchon and his successor, Foy Young, each left after one three-year rotation.

The non-contiguous nature of the monument exacerbated existing management problems. The monument was a construct, a creation of federal officials. Its artificial boundaries did not isolate it from the changes in the physical environment around it, nor did it make management easier. The allocation of resources for a trip to an outlier meant that something went undone at one of the other two areas. The combination of lack of resources and distance between the three sections made for distinctly different management practices. By the middle of the 1950s, each area was treated in a separate fashion. Betatakin had become the center of visitation. As the Shonto route became the lifeline for the area and the park developed a structure, the ruin that visitors could see from the trail became their major destination. Accessible only by horseback or on foot, Keet Seel had become less important. It lacked both signage and constant protection, while the distant Inscription House had signs but no protection other than sporadic visits from the superintendent.

As visitation increased, the content and caliber of interpretation became an issue. Because of the name of the monument, its location in the middle of the Navajo reservation, and the preponderance of Navajo people living in the vicinity, Navajo history and culture were as much an interest of visitors as the story of the Anasazi. Sensitive to the needs of the Navajo and the desires of visitors, park superintendents Brewer, Aubuchon, and Young sought to balance prehistory and Navajo culture in the interpretation program of the monument.

|

| Superintendent John Aubuchon looks over the first museum display in the original ranger cabin. |

Access to the ruins also posed problems as visitation grew. Brewer had suggested limits on visitation in Betatakin in 1939 and other Park Service inspectors concurred. Brewer had initially discarded John Wetherill's practice of keeping visitors out of Betatakin by roping off the rooms. Instead he lined out trails between the clusters of rooms in the ruin, a practice he quickly decided was a mistake. On occasion, visitors strayed from the route Brewer provided. In one instance, a Boston architect and a Santa Fe artist were permitted to walk in rooms above original ceilings. When informed, regional archeologists were apoplectic. Managing visitors in the ruin was a difficult task, for safety of the visitors and protection of the ruins mandated a need for close monitoring of visitors. By 1941, Brewer no longer allowed visitors in Betatakin without supervision. [12]

During this time, interpretation at the monument was inconsistent. Archeologists debated the meaning and significance of the various ruins that composed the monument, and the efforts of the Park Service were limited by the lack of consensus among professionals. Without a visitor center or museum, much of the interpretation was imparted by the superintendent to visitors. Under Frank Pinkley's system, visitors were not allowed in ruins without a uniformed park person. At Navajo, the distance between the contact station and the ruin made escorted visitation the only possibility. But again, the increase in postwar visitation forced changes. Brewer took as many visitors as he could, sometimes impressing Bob Black, a Navajo maintenance worker, into service conveying visitors to Betatakin. Black's command of English was minimal, and in such situations, interpretation became merely a guide service. Black recalled taking visitors to the canyon and pointing to the ruins as the extent of his interpretation. The lack of personnel, the increase in visitation, and cross-cultural inability to communicate caused interpretation to suffer. [13]

By the early 1950s, a number of changes in interpretation were necessary. After Pinkley's death in 1940, his domain in the Southwest was parceled out. Attempts to eradicate the more iconoclastic features of his leadership helped reshape NPS policy in the Southwest. The insistence on guided tours through ruins fell by the wayside as visitation grew. By the early 1950s, most monuments had self-guiding ruins trail brochures. In 1951, even a remote monument like Navajo began to experiment with a self-guiding trail leaflet to Keet Seel. [14]

Keet Seel and Inscription House were not immune to the effects of increased visitation. In the early 1950s, about thirty parties a year visited Keet Seel. A rare group might camp at the ruin, but most rented a horse and a Navajo guide from Pipeline Begishie, a local Navajo who worked at the park as a seasonal laborer and offered horses for rent. This enabled them to make the eight-mile trip each way in one day. The Park Service still did not sign the trail or provide interpretation material for Keet Seel, preferring to limit visitation to those who knew the way or were shown there by local Navajos. [15]

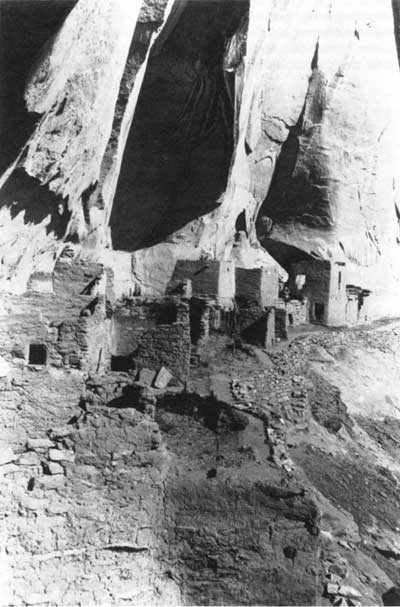

|

| Inscription House as Jimmie Brewer saw it in 1941. |

At Inscription House, the problems of Keet Seel were compounded by the nearby trading post and environmental problems. Since the 1930s, erosion had been visible in the wash below Inscription House. In the early 1940s, the wash eroded at the rate of about twenty feet per annum. By 1944, it was "positively dangerous" to reach Inscription House. In 1949, the ferocity of the flow of water caused a number of burials from the cave at Inscription House to wash out toward Lake Meade. Brewer found bones and high quality pottery in the wash after a heavy spring rain, prompting him to call for better protective measures against creeping erosion. In addition, vandalism became more common at Inscription House in the early 1950s. Unauthorized visitors sometimes dug in the ruins. Local schoolchildren repeatedly scratched initials in the soft adobe walls. [16] Clearly the Park Service had to take action.

But without an allocation of resources, any changes enacted remained largely cosmetic. Aubuchon optimistically concluded that the arduous trek to the outliers "precludes the person who has a mania for destruction," but vandalism was an endemic problem. The best mechanisms the regional office could offer were passive. Regional Director Tillotson advocated "a tightening of control over these isolated sections of the monument," but no allocation to support those sentiments followed. Tillotson reiterated his longstanding opposition to directional signs for the trails to Keet Seel and Inscription House. He approved the idea that visitors should be required to register with the Park Service before they were allowed to proceed to either of the backcountry areas. [17] But in the face of the declining condition of the two ruins, such remedies fell short of solving critical problems.

Visitors continued to come, and Navajo topped the 1,000-visitor mark for the first time in 1949-50. In comparison to other southwestern parks, this number seemed small, but it reflected a doubling of the numbers typical of the pre-war era. The small contact station and residence built in 1939 continued to be the only permanent structures at the park. They had to serve numerous functions. Besides being home to the superintendent and his family, the residence also served as an office. Jimmie Brewer set up a desk in one corner of the living room, and most of the official business conducted at Navajo occurred there. The contact station became the focus of formal interpretation at the monument. The one-room structure included a museum in a corner that displayed aspects of prehistoric and historic life in the vicinity of the monument.

|

| The congested parking area in this 1949 photo reflects the dramatic increase in visitation in the post-World War II era. |

In 1954, the little museum offered its first major exhibit. Betty Butts, a Los Angeles sculptress, and her husband Warren, an engineer, designed a diorama of prehistoric life at Keet Seel. The Buttses first came to Navajo National Monument in July 1952, taking a pack trip to Keet Seel. After visiting Mesa Verde and observing its dioramas, they wrote to Aubuchon and offered to make a similar portrayal of Keet Seel for the museum. Keet Seel was their choice, although it well served NPS purposes. Fewer visitors saw it than Betatakin, and the diorama would allow many a broader experience at Navajo than previously available to them. After more than a year and one half of research, Betty Butts began to work on the model. On August 7, 1954, the final version arrived at the monument.

The weight and size of the diorama necessitated an addition to the contact station. The diorama was more than six feet long, four feet deep, and four feet high, with structures constructed of plywood and figurines of paper mache. Buildings and walls in the diorama contained more than 3,000 small plaster stones. The Buttses spent more than three hundred hours of work on the figures, pots and implements, and vegetation. Regional archeologist Erik K. Reed authenticated all of their work. After removing the end wall, a 6 x 10-foot area with a concrete slab floor was added on to the existing structure to accommodate the diorama. [18]

The diorama was an instant attraction. Many years later, seasonal ranger Hubert Laughter remembered his first glimpse of the diorama, and a photograph captured the moment. In it, Laughter regarded the diorama with a bemused and impressed look. It was indeed new, and a genuine asset for the museum and the monument. [19]

But despite such improvements in the interpretation scheme, Navajo National Monument lacked the primary perquisite of Park Service programming. Unlike most of the other archeological monuments in the Southwest, there was no visitor center at Navajo. The makeshift contact station and its added diorama had to suffice. As late as the middle of the 1950s, Navajo still lacked the basic resources that other park areas took for granted when they began to devise their programming.

But a combination of factors converged that began to change the situation at the monument. The increase in visitation had taken a toll on the park system. Designed to handle about 25 million visits per annum, the system served more than 50 million visitors in 1955. Beginning that year, NPS officials devised a broad master plan for the system they envisioned in 1966. This would be capable of serving eighty million visitors each year. Congress supported the plan at a level not seen since the New Deal, appropriating $49 million for capital improvements in 1956 and continuing to increase the amount to almost $80 million in 1959. Conrad L. Wirth recalled later that it seemed that individual congressional representatives engaged in a form of one-upmanship, allocating even more than NPS officials requested. The ten-year plan, entitled "MISSION 66," rejuvenated the physical plant of the park system. The investment of more than $700 million built more than 2,000 miles of roads as well as modern visitor centers that replaced those built during the New Deal. Officials at many parks that had never had visitor centers looked expectantly to MISSION 66 to provide the resources for construction. [20]

At the end of the Second World War, infrastructure was the great need of the Navajo reservation. Road building was one of the top priorities. Most of the roads on the reservation were more appropriately labeled trails. The Navajo/Hopi Rehabilitation Act of 1950 set aside $38 million for road construction, $10 million of which was designated for improvement of secondary roads on the reservation. The Atomic Energy Commission also built roads to facilitate the extraction of uranium. Its first rudimentary road stretched from Teec Nos Pos to Kayenta; additional roads stretched from Kayenta to Monument Valley and later to Tuba City. These dirt highways were critical to the development of an infrastructure on the reservation. [21]

During the 1950s, the Navajo Nation began to invest in capital programs on the reservation. With the wealth from the nascent development of its natural resource base, the tribe embarked on a number of programs. Constructing roads became one of the most important. In March 1958, the Tribal Council appropriated nearly $1,000,000 for road building as a means to combat an economic recession. Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater arranged a similar amount from the Bureau of the Budget. Much of the money was earmarked for the western reservation area surrounding Navajo National Monument.

The addition of paved roads on the reservation offered many benefits. Besides encouraging industry, the roads brought travelers to see the region and made the Navajo people more mobile. After intensive and drawn-out planning, the road-building program began in 1958. One of the first tracts paved was the trail between the Utah border and Kayenta, a little more than twenty miles through the canyons from Betatakin. Following closely was the implementation of a plan to link Kayenta and Tuba City by paved road. Although a difficult area in which to build, a road through the heart of the western reservation was essential if the leaders of the Navajo Nation were going to pursue development and tourism as strategies for the economic advancement of its people. [22]

Paved roads in the region had clear implications for Navajo National Monument. A road would end the isolation that had characterized the monument since its establishment in 1909, bringing many more visitors to the park and intruding upon existing relationships between the Park Service and its neighbors in the Shonto area. But combined with the MISSION 66 programs, the idea of a paved road spurred the first stage of modern development at the monument. [23]

MISSION 66 for Navajo was the most comprehensive development proposed in the history of the monument. When it debuted in 1957, MISSION 66 for Navajo proposed a headquarters building for the monument, the first of its kind at Navajo, and the construction of an approach road. There was also a provision for the Bureau of Public Roads to build an approach road to the monument from the new U.S. Indian Service highway 1 (U.S. 160). But Navajo National Monument was very small, and the MISSION 66 program could not begin before the NPS reached agreements governing use of land in the region with the Navajo Nation and individuals in the vicinity of the monument.

In 1956, a superintendent who would leave a larger-than-life mark on the monument came to Navajo. Arthur H. (Art) White was a "superintendent's superintendent." A rugged man possessed of personality and charm, he excelled at stretching what he had. Typical of the jack-of-all-trades types of people who worked at remote park areas, he was handy with tools, good at salvaging equipment and rebuilding it for park use, and resourceful in all matters. White was a real leader, a man with perspective who could inspire, and who helped those who needed it. He installed the radio telephone to replace closed-circuit NPS radio, added fencing at Keet Seel and Inscription House, and made many other improvements at the monument.

White and Navajo National Monument were made for each other. With a background in anthropology, he was well versed in Navajo culture. White was a true old-time Park Service man who was immensely popular with the seasonal and permanent staff that grew during his nine years at the monument. "We work fourteen to sixteen hours a day out here," he told Ranger Bud Martin when the latter arrived in 1962. White was under a diesel front-end loader at the time. [24]

This kind of commitment characterized the Park Service in the days before the rigid enforcement of federal regulations. Most park personnel thought nothing of working unpaid overtime or performing whatever task came along, no matter what their job description. These iconoclasts invested themselves in the park system, albeit in a sometimes unorthodox fashion. Yet their actions created an esprit de corps that made those who worked the long and often lonely hours at remote areas into a close-knit clan that recognized the common ground they shared.

Park Service people at Navajo faced a life of real privation. When Emery C. (Smokey) Lehnert arrived as the second permanent employee in 1958, the only available housing was an 8' x 32' foot house trailer. The Lehnerts added a baby boy to their family in July 1959, making a minute living space even smaller. Because inclement weather for as much as six months each year limited access to the outdoors, the trailer became oppressive. The Lehnerts suffered from an advanced case of "cabin fever" in the winter of 1959-60, with Mrs. Lehnert affected so thoroughly that, under physician's orders, she left the park in the spring for an extended vacation. Isolated in inadequate quarters, far from family and friends, and trapped by snowfall for extended periods, life could be miserable for park rangers and their families. Later the Lehnerts received permanent housing, alleviating a symptom but not necessarily the cause of some of their discontent. [25]

White came to Navajo at precisely the correct moment to utilize his talents. With his experience, perspective, and saltiness, he provided the leadership necessary to administer growth and attendant change. White gave his staff "enough rope to hang yourself with or do something with it," Martin recalled, leading by example and expecting his staff to follow. During his tenure, there was little left undone at Navajo. [26]

White also developed close relationships with Navajos in the area, building on the tradition of Hosteen John Wetherill and laying a foundation for future superintendents. White learned Navajo silversmithing while at the monument, an art for which he became renowned. He also extended a helping hand to many of the neighbors of the park, providing an informal road grading service outside park boundaries. He and Bob Black became close friends, both speaking fondly of their memories of each other almost thirty years later. Bob Black recalled with a twinkle that after White used the road grader, Black would have to go smooth out the squiggles and rough spots left in the road. White remembered Black as one of the best people he had ever met. [27]

|

| This grader was an essential part of keeping the dirt road to the monument open. |

The coming of the paved road became a critical step in the gradual elimination of the obstacles that hindered the growth and development of Navajo National Monument. When the MISSION 66 program for the monument debuted, it was low on the list of agency priorities. Regional Director Hugh Miller regarded the plan for a $179,000 visitor center at Betatakin as "startling even with improved roads and increasing travel." He required some evidence that the level of visitation would increase enough to merit such a program. But as Superintendent White announced in one of his monthly reports, the monument was "land-bound," for it lacked a a surrounding area sufficiently large to implement a substantive capital development program. [28]

The boundaries of Navajo were minuscule in comparison to other similar monuments in the Southwest. The Betatakin section was a mere 160 acres. It encompassed the canyon area; only a very small area on one of the rims was inside monument boundaries. During his tenure, James W. Brewer privately speculated that even the ranger cabin built in 1939 might be outside park boundaries. Keet Seel was the same size, while Inscription House was only 40 acres. When its officials cut the monument down to avoid conflict with grazing interests in 1912, the GLO permanently limited growth. Before any capital improvement plan could be implemented, more land was necessary. [29]

Yet the combination of MISSION 66 for the park system and the road-building program of the Navajo Nation generated momentum that made the development of Navajo National Monument a possibility. The forces of modern civilization were beginning to act on the western reservation in a comprehensive manner. The leaders of the Navajo Nation, Paul Jones, who served as chairman of the tribe from 1954 to 1962, and his successor Raymond Nakai, implemented new services and encouraged economic development projects. [30] To meld its holdings into this changing world, the Park Service had to further similar programs.

Only one way to get more land existed. Some kind of arrangement had to be struck with the Navajo Nation, the Shonto Chapter, and the individuals in the region. "We must either get the land or permission to build off the monument," White insisted in July 1958. [31] But despite the interdependent nature of life in the region, NPS officials recognized that a lease, purchase, or other form of acquisition would limit the autonomy to which agency officials were accustomed. As foreign supplicants in the Navajo homeland, the NPS needed to be prepared to compromise.

The long and complicated process of orchestrating an agreement began in 1958. Regional Director Hugh Miller instructed White to begin informal, low-level discussions about acquiring land. The land on the rim of Betatakin Canyon belonged to Bob Black, who had almost twenty-five years of service at the monument. White and Black reached an accord, circumventing the need for approval at the chapter level. Subsequently, the Park Service convened a meeting with a number of Navajo leaders. Prior to the meeting, White and Leslie P. Arnberger, assistant regional director of the Southwest Region, discussed the issue. White wanted to acquire an entire 640-acre section for the monument. Buildings at the monument were already on reservation land, and White wanted to assure that the monument could grow if needed. Arnberger disagreed, and the two compromised on forty acres. [32]

At the meeting in the superintendent's house at the monument, Art White, Regional Director Hugh Miller, Les Arnberger, Navajo tribal representative Sam Day III, Frank Bradley Jr., and tribal employee Jim McNee met to work out an agreement. Day proposed an exchange: twenty monument acres for twenty Navajo acres and the tribe would grant twenty more. After viewing the land, Day was willing to forgo the exchange. He told the Park Service to just ask for the land. The Navajo Nation would not be interested in an exchange for such visibly unproductive land.

But the idea of an exchange was unsuccessful, and throughout the rest of the 1950s, little progress occurred. After giving up on the idea of an outright exchange, the Park Service subsequently sought some form of agreement to use land adjacent to the monument. But acquisition remained the paramount goal for the NPS, and when the chances of acquiring some portion of adjacent land seemed good, NPS interest in an agreement for use declined. When agency officials found avenues of acquisition blocked, they sought an agreement. From the perspective of the Navajo Nation, acquisition at the monument was linked to the transfer of some other land to the tribe. Antelope Point and the Page area were both suggested during negotiations, but no consensus emerged. The result was a stalemate. Yet from regional director to superintendent, everyone recognized that Navajo National Monument needed additional area. [33]

The response of the staff was a mixture of excitement and trepidation. In July 1958, when Smokey Lehnert came to the monument, he and Art White became a formidable duo. They responded to the impending changes in colorful and descriptive fashion. With the increase in paved roads, the monument area "will have had it," White remarked. Nonetheless, the process continued. In 1959, crews began to pave the section of road between Tuba City and Kayenta. By the time it was completed, it left only one section of dirt road to the monument: the tract from the main highway through Shonto and on to Betatakin. [34] As it became easier to reach the monument and the number of travelers on the newly paved roads of Navajoland increased, White and his staff had to prepare for significant changes at Navajo.

The impact of increased visitation posed one major issue. Since its establishment in 1909, Navajo had been protected largely by its remote location. Easy access would clearly alter existing patterns of visitation. Visitors who previously would not have tackled almost 100 miles of dirt road told White and Lehnert that the increasingly small unpaved sections only spurred them forward. For staff members, increased visitation was clearly a mixed blessing. Superintendent Art White seemed to dread the arrival of the "beer can and kleenex" crowd, the sedentary traveling public, unappreciative and unwilling to make a sacrifice to understand the place on its own terms. "God or MISSION 66 help this monument" if the Tuba City-Kayenta road was paved, White caustically remarked in March 1958. NPS personnel recognized that the roads would change the character of the monument as well as the experience of visitors there. They were also cognizant that the past as they had known it was already gone. By the early 1960s, time was running out. [35]

Negotiations between NPS and the Navajo Nation were the clear solution to the lack of land and facilities faced by the Park Service. After a strong beginning, the negotiations stalled in 1958, and relations deteriorated. Issues of land transfer and rights of way for potential entrance roads slowed progress toward an agreement. The NPS and the Navajo Nation had different goals, and as economic development began in earnest on the reservation, the Navajo Tribal Council under Paul Jones expressed resentment towards the Park Service.

But the NPS had much to offer the Navajo people. As the Navajo Nation tried to attract entities with economic potential, it found obstacles. The virtue of the reservation most easily converted into dollars was its spectacular scenery, history, and prehistory. The desire to develop resources for visitors pushed the Navajo Nation into simultaneous cooperation and competition with the Park Service. Late in the 1950s, the Navajo Tribal Park system became an important lure for visitors. Monument Valley, the location of numerous John Ford and John Wayne westerns, became a major attraction for visitors. Yet opening a tribal park and serving finicky American visitors were two separate and distinct functions. The Navajos needed the expertise that the Park Service developed during nearly fifty years of visitor service. NPS officials offered training for tribal rangers as one measure to improve relations and installed an exhibit at the annual tribal fair. Navajo leaders also eyed Canyon de Chelly in particular, with lesser emphasis directed toward Navajo, Wupatki, and Sunset Crater national monuments as possible additions to their fledgling park system. [36]

In addition, the process of negotiating an agreement strengthened the relations between Navajos and the Park Service. In November 1959, Maxwell Yazzie, one of the most distinguished Navajo attorneys, spent four days at the monument in an effort to secure the agreement. Yazzie helped convince local Navajos of the value of the visitor center and its road, secured rights-of-way from individual land holders, and offered his opinion on the chances of the proposal. It was a learning experience for both sides that helped smooth out the differences in perspective. [37]

The Park Service also revived an old concept that had major implications for the region. The debut of the "Golden Circle" of national park areas, including Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Rainbow Bridge, and Navajo, was the direct result of the southwestern strategy pursued by Stephen T. Mather and Horace Albright in the 1920s. The concept linked numerous park areas in this largely undeveloped region into a comprehensive package designed to attract visitors. The Park Service had utilized a convenient monument-to-park strategy to bring Grand Canyon, Zion, and Bryce Canyon to national park status in an effort to make the Southwest the focus of American travelers. This focus provided the Navajo Nation with a ready supply of visitors and encouraged the rapid development of support facilities.

It also pushed the NPS and the Navajo Nation towards an agreement at Navajo National Monument. Both sides had something to offer each other, and with much at stake--a potential anchor for economic development on the reservation for the Navajo Nation and the ability to develop and protect an important prehistoric resource for the Park Service--the two sides moved towards a solution. With the opening of the first Navajo Tribal Park at Monument Valley in 1960, the ties strengthened. Yet protracted negotiations were necessary, and the process of arranging a final accord lasted more than three years.

NPS officials found the process frustrating. By September 1960, the Southwest Regional Office had drawn up an agreement to which Tribal attorneys agreed in principle. In March 1961, White chafed at the slow pace. Recognizing the need for facilities to handle the increase in visitation, he pressed for the acquisition of land. The following May, the Advisory Committee of the Tribal Council approved the draft of a memorandum of agreement for interim use of an area adjacent to the Betatakin section. NPS officials sent a final version of the memorandum for the Navajo Nation and BIA to sign and awaited a reply. More than a year later, no word had come from the tribe. In November 1961, Art White began a countdown. "We still have ten months grace here until we are really overrun," he informed his superiors. When the Navajo Nation finally responded, significant portions of the memorandum had been changed. NPS officials determined that they could live with the changes, for an interim agreement to use land increased the chances to implement MISSION 66 programs at the monument. [38]

The result was the Memorandum of Agreement, signed on May 8, 1962, a compromise designed to further the interests of both the Navajo Nation and the Park Service. In reality, no one got exactly what they wanted. The NPS received the right to use 240 acres on the rim of Betatakin Canyon from which to manage the monument. In return, the Park Service agreed to help the Navajos acquire Antelope Point, near the Glen Canyon Dam project, for development purposes. NPS officials were to use their influence to get the area ceded to the Navajo, and in return, Navajos would give up land at the monument in "fee title." This proposed program did not work. The Navajo Nation was reluctant to give up any land, the cessation of Antelope Point stalled, and agreement across cultures was very difficult to reach. In the final cession, secured by the Memorandum of Agreement, the land was "loaned" to NPS as an interim arrangement to allow development to proceed before formal exchange could be enacted. NPS officials accepted this proposal because they feared that legislation enlarging the monument would remain beyond their reach. In the late 1960s, NPS management documents identified acquisition of fee title to the 240-acre Memorandum of Agreement tract as a serious potential problem. By 1990, no change in the status of the land had been accomplished.

The agreement happened just in time. In the summer of 1962, paving continued on the last stretch of the Kayenta-Tuba City road. A dedication of the road was planned for September 15. When finished, the road eliminated the last section of unpaved arterial highway in the western reservation. It was a "red-letter day for this part of the country," Art White remarked. But to face the implications of the road, the Park Service needed the memorandum. [39]

The Memorandum of Agreement formalized the long-standing interdependent relationship between the park and the Navajo people who lived nearby. By 1962, visitation at the monument rose to 6,603. The park needed more seasonal workers, greater quantities of materials, and more help with services such as the horse trips to Keet Seel. Navajo people perceived an economic opportunity in the development. Under the terms of the agreement, the NPS was obliged to provide a room for Navajos to sell crafts at the planned visitor center. Regional Director Thomas Allen had resisted this idea, arguing that a more typical concession arrangement was better for the Park Service. The Navajo Tribal Council had introduced the idea and refused to relent. Recognizing that the agreement potentially unlocked vast amounts of money for the monument, regional officials accepted the provision. The park and its neighbors were closely bound in a relationship that benefited both. The agreement made interdependence into a de jure rather than de facto reality.

Yet there were problems that remained from the Memorandum of Agreement. It was only a temporary measure, designed to allow the NPS to develop Navajo before final resolution could be reached. But a permanent transfer of land remained elusive. Throughout the 1960s, efforts to solve numerous land and development issues surrounding Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Rainbow Bridge National Monument, and Navajo National Monument continued. By 1966, an impasse had been reached. The Navajo Nation did not want to give up any more of its land, while the Park Service could not give away its holdings without getting something in return. In 1966, the NPS offered a three-for-one swap of land at Betatakin and Rainbow Bridge for a much larger tract of federal land at Antelope Point that the tribe coveted. The Navajos rejected the exchange. "If the Tribe had its way," exasperated Regional Director Daniel Beard wrote NPS Director George Hartzog, Jr., "the 'exchange' would be one-way--all take and no give." If the Park Service backed down unconditionally, offering to take less or give more, Beard thought the Navajos might take it as a sign of weakness. This could be a prelude to further demands that Beard felt were unreasonable. [40] Park Service officials were at a loss. They felt they made more than generous offers that were rejected out of hand. But a cultural awakening had occurred, clearly changing the climate in the region in a less than decade.

During that time, the Park Service became frustrated by its dealings with the Navajo Nation. The Navajo Nation sought NPS land and the right to develop visitor services for places like Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, while the Park Service still wanted clear title to the land at Navajo as part of an elaborate system of exchange. A four-year effort to resolve the use of lands near Glen Canyon became an interminable burden. In one instance in 1969, an agreement "almost made it," as Regional Director Frank Kowski was informed, but was rejected by Tribal Chairman Raymond Nakai as not being sufficiently favorable to the Navajo. Only when Regional Director Frank Kowski threatened to withdraw NPS support for an economic development by the Navajo aimed at serving NPS visitors did any sort of agreement become reality. On March 6, 1970, Kowski, Solicitor Gayle E. Manges, and Nakai met in Window Rock to work out the details. The result was an agreement that allowed the Navajo to develop the south shore of Lake Powell. [41] But because of the difficulty in reaching a solution, resolving issues at Navajo National Monument was forgotten.

By 1970, the Navajo had become far less likely to permanently cede any tract of land to a federal agency than they had a decade before. The late 1960s awakened the Navajo people and their political structure to two realities: their identity was threatened by encroaching mainstream culture and the land they held was their only cultural and economic protection. Demand for energy exploration of the reservation had increased, although in more than one instance, the Navajo felt that they were exploited. They looked warily at the outside world, including the Park Service. Despite a number of cooperative agreements with the Park Service that allowed the Navajo to offer concession services to visitors at a variety of parks, the NPS could not wrest free the 240 acres at Betatakin covered in the Memorandum of Agreement. As the obstacles mounted, the idea of outright acquisition faded, and the temporary agreement took on a semblance of permanence.

That temporary agreement had lasting effect. By 1962, Navajo National Monument had been transformed. The most serious obstacle to its development, the lack of roads and easy access, had been eliminated, and the monument was on the list for the ample funds derived from MISSION 66. The cocoon that had been the monument, the narrow world in which NPS people and their neighbors previously lived, had been opened up to the mass of Americans. The very values that attracted archeologists, park people, and visitors to the monument were in danger of being overwhelmed.

Between 1938 and 1962, Navajo caught up to the rest of the park system. It faced the same problems, compounded by its non-contiguous nature and its location as an outpost in Navajoland. Although the park was well managed, park staff recognized their limitations as the world around them, already beyond their control, changed rapidly. The need for more land was paramount; efforts at expanding the monument reflected this reality.

Before the Memorandum of Agreement, the agency regarded MISSION 66 for Navajo as a long-range plan rather than a program to be implemented. At higher levels, officials recognized the unique limited position of the monument and were not prepared to commit resources. MISSION 66 was aimed at parks with higher levels of visitation. Growth at the monument had to wait until the acquisition of land on which to build visitor facilities.

This made an already dire situation even more urgent. Navajo lagged behind the rest of the park system, and the development of roads and other facilities in the area around the monument accentuated the gap. By the time development occurred, it could only bring the monument up to current demand. Planning for the future would have to wait.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

nava/adhi/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006