|

Navajo

A Place and Its People An Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER V:

THE MODERN ERA

The signing of the Memorandum of Agreement at Navajo National Monument was the pivotal moment in the history of the monument. It terminated the set of problems that existed prior to the acquisition of the 240 acres allowed under its terms, but created entirely new issues in its wake. The memorandum began the transformation of Navajo into a modern park area, complete with capital facilities, large numbers of visitors, and most of the amenities of the rest of the park system. The memorandum also restructured the relationship between the park and the Navajo Nation, highlighting and changing the close relationship between the park and the people of the western reservation.

This agreement served as the catalyst for the implementation of the MISSION 66 program at the monument. By effectively enlarging the monument by 240 acres on the rim of Betatakin Canyon, the memorandum provided space in which the Park Service could construct the kind of park facilities that had become typical in the park system. Perhaps rushed by the need to get the proposed program underway during the halcyon days of MISSION 66, the interim agreement was less than the Park Service wanted. But it had the impact that all agreed was essential. An ostensibly temporary move, it offered permanent advantages.

The memorandum also formalized existing ties with the Navajo Nation, in effect putting the park on the same level as the Navajo people. The implementation of MISSION 66 at the monument injected large amounts of money into the region and provided numerous economic and employment opportunities for Navajo people and others. As the catalyst for increased visitation, the memorandum also helped transform the economy of the region.

Navajo National Monument had always been dependent on the people who lived nearby. The agreement formalized that relationship at the exact moment that Navajo people began to feel a greater sense of empowerment. As a result, the NPS sometimes felt the animosity directed at mainstream America in general, complicating relations between two increasingly interdependent communities. After 1962, the Park Service had to move carefully.

With the rapid advent of MISSION 66, the monument experienced rapid growth that almost overnight gave the park modern facilities and responsibilities. The change in level of management was difficult because of the figurative distance that had to be covered. A rapid transition to modern park management fraught with difficult decisions in a changing administrative climate followed.

When MISSION 66 for Navajo National Monument debuted, it offered a comprehensive program of development for the monument. The prospectus instituted direction in a manner that had never before been attempted at Navajo. The detailed proposal planned an entire range of visitor facilities and services, construction, maintenance, and staff. But in the era before the Memorandum of Agreement, the program was a wish list. Chief among the needs articulated in the prospectus was more land. Only when it was acquired could development progress. [1]

The implementation of MISSION 66 at Navajo had begun slowly. Because of the clear sense among park people at the national, regional, and local levels that there was not enough room at the monument to begin a comprehensive program, the Memorandum of Agreement accelerated a process that had been previously stifled. The rapid growth and development of the monument was a result. So was a marked upgrading of the services and facilities available at Navajo National Monument.

Conditions at the monument before the beginning of MISSION 66-funded development had changed little since the 1930s. Former Ranger Bud Martin recalled that during his stay in the early 1960s, a diesel generator supplied electrical power for the park. The situation for park employees was typical of remote areas. The only residences for park personnel were the stone superintendent's house, built in 1939, one hogan, and three old small trailers. Martin, his wife, and two children lived in one 27-foot trailer. "We considered it an adventure," he wryly remarked many years later. [2]

Visitor facilities were as rudimentary. The visitor center was a small one-room cabin just below the superintendent's house. Most of the time it was unmanned, and if no one was there when visitors arrived, there was a written greeting that told them they could see the ruins if they walked the Sandal Trail. A shelf held a pair of binoculars visitors could borrow, but after someone walked off with them, the practice was discontinued. There was no need for law enforcement at the time, and the one gun on the premises was a World War I-issue pistol, most likely not fired since, that was locked in the safe. Postcards were for sale; anyone who wanted one could just take it and leave the money. People could also sign up for a tour down to the ruins, but as Art White recalled, "the rationale then was that anybody that would drive out over that goddamn road had to really want to get to [the ruins] . . . if they were that interested in it, they weren't going to tear it up." A six-unit campground existed, the only accommodations available at the monument. The trading post at Shonto was the only place to stay.

One object of visitor attention was the home-made shower at the monument. Monument personnel and visitors showered in a canvas-covered area made of upright poles that had two fifty-five gallon drums of water heated by the sun. There was a hand-held nozzle that stemmed from the barrels with holes poked in it to increase the flow of the water. By the early 1960s, most needed little other than the shower to remind them of the remote situation of Navajo National Monument. [3]

Even after the Memorandum of Agreement, MISSION 66 began slowly. Although spending for development began at Navajo in 1962, 1964 was the first year in which the appropriation was large enough to make an impact on the park. Prior to 1964, MISSION 66 expended just $30,000 at Navajo. Most of the funding went for small-scale projects, such as house trailers in which permanent and seasonal rangers could live. Getting even that relatively small amount took energy and persistence. Art White consistently turned in blank pieces of paper as his reports on activities at the monument. He correctly assumed that this would catch someone's attention. But a coercive maneuver did more good. When Eivind T. Scoyen, associate director of the Park Service, made a southwestern swing in the early 1960s, White took the opportunity to make a pitch for Navajo. Scoyen tried to avoid making a visit across the newly paved highway, but White prevailed upon Regional Director Thomas J. Allen to bring Scoyen to Navajo. Unhappy about the visit, Scoyen arrived in a bad mood. But White carefully arranged a tour and a walk to Betatakin for the assistant director. After Scoyen visited, more than $1.5 million for Navajo appeared in the next NPS appropriation. Many of White's peers expressed admiration for White's prowess and surprise at his success. [4]

The real expenditures followed 1964. Between 1964 and 1966, the monument received and spent more than $1.5 million of MISSION 66 money. As the development program moved forward, its cornerstone, the new visitor center, became more than a gleam in the superintendent's eye. A 9.3 mile approach road from the east was planned to finally give the monument a paved access road. Other projects included employee residences and trailers, a power system and a utility building, and water and sewer systems. The combination of facilities, amenities, and resources altered the very nature of the experience of visitors to Navajo National Monument.

One factor was the marked increase in visitation that resulted from the paved roads through the western reservation. Prior to 1960, it was a long trek to Navajo National Monument. It was too far from civilization, over which cars had to travel too many washboard-like dirt roads. But pavement to within fifteen miles of Betatakin Canyon nearly doubled the number of visitors. In 1959, recorded visitation totaled 3,053; only two years later, in 1961, the number reached 6,175. In 1963, visitation reached 10,832, only to nearly double again to 20,401 after the opening of the new paved approach road (U.S. 564) in 1965. [5]

Responding to the increase in visitors required tremendous growth in the number of staff members. The hiring of Smokey Lehnert in 1958 inaugurated a period of rapid growth. At the time, the superintendent and ranger usually could expect two seasonal rangers in the summers. In 1965, merely seven years later, there were five full-time permanent staff people, including the superintendent, the chief ranger, two more rangers, an administrative assistant, and laborers. There were also four seasonal rangers each summer, providing an ample staff for the level of visitation.

The development of the monument was a process that went through stages. The acquisition of land through the Memorandum of Agreement inaugurated the transformation, and the construction of the primary capital facilities, the visitor center and the paved approach road, followed soon after. The final stage involved incorporating the changes into the day-to-day activities of the monument.

The agreement was only a catalyst for change, not its cause. Plans to develop the monument predated the acquisition. Both the visitor center and the paved approach road were in the works before the memo; both were dependent on the acquisition of land. The need for a real visitor center had been expressed in 1952 when John J. Aubuchon first created a museum at the monument. [6] Throughout the 1950s, Art White recognized that the encroachment of the modern world would change the level of service that the Park Service had to deliver. The prior efforts of the staff at Navajo contributed to recognition of the need. But the list of agency priorities, the limited resources with which to meet them, and the lack of space at Navajo in which development could be implemented slowed the process.

The construction of the Keet Seel diorama and the positive response of visitors made clear that museum interpretation at Navajo was desirable. But without more land, there was no place to put a visitor center at Navajo. It remained a low priority until after the signing of the Memorandum of Agreement. Then it accelerated, moving rapidly through the design and construction phases.

The approach road followed a similar pattern. In the mid-1950s, the Bureau of Public Roads recommended the construction of an approach road. The first step in the process was the acquisition of a right-of-way from the Navajo Nation. The Park Service sought it at the same time negotiations about the memorandum of agreement began. The negotiations were a long and time-consuming process, but the Park Service finally received permission in 1962. The increasing recognition of value of tourism by the Navajos was one important factor in securing the right-of-way. The election of Raymond Nakai as Tribal Chairman in 1962 also helped. Nakai advocated economic development and was willing to pursue alliances that would further such goals. [7]

As the beginning of the construction of the Visitor Center approached, excitement at the monument increased. The Ganado Construction Company of Ganado, Arizona, was retained to build the structure. From the starting date of November 13, 1963, the company was given 270 days to complete the structure. Despite deep snow and extremely cold weather, the company finished the job on June 4, 1964, more than two months ahead of schedule. The new Visitor Center was positively received. "It is a good job well done," federal inspector E. L. Holmes remarked late in May 1964. "The government has a good building." The visitor center "went up pretty damn fast," Art White later remarked. "We had a good contractor." [8]

The development of the road followed a similar pattern. Acquiring the right-of-way took much longer than building the road itself. With MISSION 66 money for the road, the project proceeded smoothly. The James Hamilton Construction Company of Gallup, New Mexico, served as the contractor, and the road came closer and closer to the monument. On July 24, 1965, the visitor center, the new approach road, and the new campground opened. Navajo had, in the words of its new superintendent Jack R. Williams, "taken on the aura of a much larger park operation." [9]

Yet many long-time staff members were ambivalent about the changes. Most generally recognized the necessity and inevitability of development and access, but seemed to resent the transformation that followed progress. They recognized that Navajo National Monument and the surrounding area would cease to be as they had been. The sentiments of Robert Holden, the administrative assistant at the monument, typified their perspective. As he left the park for a new assignment the day the new road opened, he could see that an era had come to an end. Many years later, Art White recalled his feelings at the time. He "hated" to see the access road and the development take place, for it meant that visitation and the attendant problems would increase. Like many of the others who selected Navajo National Monument as a place to avoid the most repugnant aspects of the modern world, White "liked it the way it was." [10]

Nevertheless, the day the road opened, a new breed of travelers could come to the monument without inconvenience. The facilities at the monument were set to accommodate their desires. The new visitor center included a museum gallery and an auditorium with orientation slide shows. The Southwestern Parks and Monuments Association expanded the number of items it offered for sale. Campfire programs were added to help fill the evenings for the larger numbers of overnight campers. Outside, the Sandal Trail took visitors to an overlook from which they could see Betatakin ruin. Much of the rigor that had characterized the trip to Navajo was gone, and the people that followed the path of pavement from Tuba City or Kayenta and turned at the new turnoff to the monument seemed less appreciative than those who had come up the dirt road from Shonto.

|

| This photo of the new Visitor Center and the surrounding suggests the degree of change that resulted from its construction. |

On June 19, 1966, the dedication ceremony for the Visitor Center underscored the changes. Up the road came carload after carload of dignitaries. More than 1,000 people attended the event, a great deal more visitors in one afternoon than in many of the individual years in the history of the monument. Arizona senator and former Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater was the principal speaker, Navajo Tribal Chairman Nakai also spoke, and an aging Neil Judd closed the ceremonies. Floyd Laughter, Hubert Laughter, both former park employees, and Mailboy Begay, all of whom were medicine men, blessed the building, their ceremony captured in photographs, and the Navajo Tribal Museum Dance Team performed at the ceremony. At last, Navajo National Monument had visible testament to its participation in MISSION 66. [11]

|

| Navajo Medicine Men prepare to bless the new Visitor Center. From left to right are: Hubert Laughter, Ben Gilmore, Floyd Laughter, and Mailboy Begay. |

Yet all those people clearly signaled a different kind of future. Navajo National Monument had been unique. Among all the park areas in the Southwest, it had been one of the last throwbacks to an earlier era of management. Protected by its isolation, it had grown apart from other park areas, as closely tied to its locale and the traditions of that environment as to the rest of the park system. As the cars came up the road, its ties began to shift toward the modern world.

Nor was the massive construction of the mid-1960s the end of the MISSION 66 at the monument. As late as 1968, programs conceived under MISSION 66 were still underway at Navajo. Many of these were associated with interpretation and visitor service, while some included construction of additional visitor facilities. The campground was enlarged to twelve sites, and the overlook platform at the end of Sandal Trail was also constructed. [12]

|

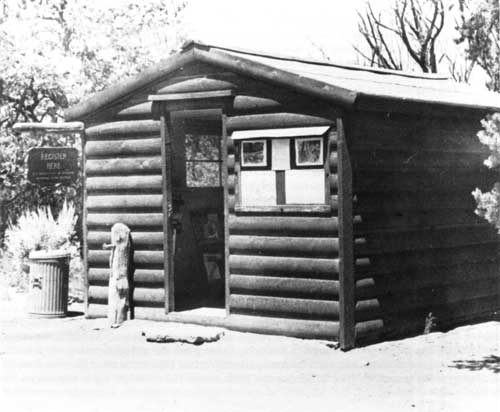

| Before the Visitor Center, this converted storage shed served as the contact station for visitors at Navajo National Monument. |

One major construction project was a trail from the visitor center to Betatakin Canyon. This move sought to accommodate the rash of visitors, many of whom wanted access to the ruins that was as easy as reaching the monument. Since the construction of the road from Shonto in the 1930s, Tsegi Point had been the primary route to the canyon floor. But the nearly two-mile trek from the visitor center discouraged many visitors. The new cross-canyon approach alleviated that problem, for visitors could walk out of the visitor center and instantaneously be on the trail. Navajo day laborers who "were really great with their stonework," as Robert Holden recalled, built the trail, which was funded out of the Accelerated Public Works (APW) program. Yet the new trail created hazards of its own. Robert Holden recalled that it "seemed rather dangerous" even as it was being constructed. [13]

The construction of the cross-canyon trail reflected one of the most crucial historical problems of the monument. The original park facilities had been located across the canyon from the ruin because it was the only place on the rim to which the NPS had any claim. Most of the few visitors of that era thought little of a strenuous trek. But the road and the visitor center brought people unaccustomed to rigor. They sought a convenient way to the canyon. As the visitor center went up across the canyon from Betatakin, park officials knew they needed a more accessible way to the bottom: the construction of the cross-canyon trail followed.

This suggested that despite all of the advantages of the Memorandum of Agreement, land itself was not enough for Navajo. More specifically, the NPS needed the right tract of land on the rim, which the construction of the new trail revealed was not the 240 acres in the memorandum. Hamstrung by historical precedent, the NPS selected the most available tract. Access to the ruins that was too difficult for a large percentage of visitors was one consequence.

The real transformation of the monument had only begun. The opening of the road increased the pace and scale of change in the operations of the monument. In 1965, visitation topped 20,000 for the first time. By 1969 there were major differences in the level and type of visitation. That year, 75,812 people, of whom fewer than 5,000 made the trip to Betatakin or Keet Seel, visited the monument. Most of the visitors never left the visitor center, increasing the importance of programs and decreasing that of the ruins. The increase in visitation forced Park Service leaders to reevaluate their plans for Navajo. [14]

Almost everything associated with the monument changed as a result of MISSION 66. The facilities changed the nature of the responsibilities of park personnel. Prior to paved roads and the MISSION 66 development, most of the visitors who came to Navajo were specifically interested in the ruins of the region. There was no other reason to hire a pack trip from John Wetherill or travel the uneven, dusty roads to the Shonto trading post. Signs had even been a problem. As late as the end of the 1930s, visitors traveling from Shonto to Betatakin had to guess the correct direction. As a result, those who came needed little interpretation from park staff. Many knew more about the ruins than did NPS personnel stationed at Navajo. Prior to the 1960s, casual visitors simply did not appear at the contact station.

But easier access meant new responsibilities for park staff. As Navajo ceased to be an out-of-the-way place, more typical visitors came to the monument. They had their two weeks in the summer and sought the spiritual enlightenment and cultural iconography of the national parks. Many of these came to Navajo because it was in the park system. They expected to see a statue or some other type of monument and were rarely adventurous enough to make the long trek from the contact station to the canyon bottom or take the horse trip to Keet Seel. When they recognized the difficulty involved in reaching Betatakin, they felt disappointed. After all, they had driven nine miles out of their way on the approach road. More numerous sedentary visitors forced park staff to reconsider its method of managing and interpreting the ruins.

For the first time, guided tours for visitors could not provide a sufficient level of interpretation. With slightly more than five percent of visitors taking such tours, the Park Service had to provide other means of interpretation. As a result of the New Deal and MISSION 66, visitors had developed high levels of expectation about the service they would receive. Most expected all the amenities of home when they saw a Park Service uniform. That included a short and easy walk to the object of their interest. With a visitor center atop the mesa and the ruins nearly 600 feet below in the canyon bottom, that easy walk was impossible at Navajo.

The visitor center provided the opportunity to broaden the scope and depth of interpretation at the monument. By the late 1960s, Americans were well on the way to becoming a nation of spectators. As an institution, the visitor center was equipped to meet those kinds of expectations. With a gallery, auditorium, gift shop area, and the adjacent Navajo craft store, Navajo National Monument seemed, to the most callous, an Indian mini-mall. It also reflected the kind of accommodation necessary to reach the typical American traveler.

The opening of the visitor center added new dimensions to the presentation of Navajo culture at the monument. Within three years of the dedication of the visitor center, Superintendent William G. Binnewies initiated a program in which a Navajo rug weaver in traditional dress worked near the hogan exhibit. This was the first instance in which the monument included live activities. Shortly after, this program was followed by live Navajo fry bread demonstrations at the campfire circle by Park Aid Rosilyn Smith and her family. Douglas Hubbard, deputy director of the Harpers Ferry Center, remarked that the program had everything: "action, the sharing of human experience, [and] communication in the form of talk and taste . . . . We are not surprised it is a hit with visitors and want to add our applause to theirs." [15]

The major consequence of increased access was increased impact on each of the three sections of the park from the exponentially larger number of visitors. The percentage increases were similar, but because Keet Seel and Inscription House had far smaller totals prior to the advent of MISSION 66, the numbers remained small. But more visitors meant more impact; particularly on fragile resources such as Keet Seel and Inscription House.

In the aftermath of MISSION 66 and in no small part as a result of the escalation of the Vietnam conflict and the inflation it spawned, the resources available to the Park Service began to level off. For Navajo in particular, this had grave implications. The new developments and better access meant that the cost of maintenance, interpretation, and management was certain to increase. But after the construction of the MISSION 66 facilities there, many in the NPS turned their attention elsewhere. Without commitment of resources to manage the new facilities, the staff at the monument faced severe limitations.

Difficult policy choices resulted from the situation. After the great commitment of resources in the early 1960s, agency emphasis shifted away from Navajo. Park personnel no longer found quick and comprehensive responses to their needs. In one instance in January 1968, the Western Planning and Service Center in San Francisco informed the park that the badly needed master plan for Navajo was not on its "priority list or work schedule." [16]

Among the three sections of the monument, Inscription House faced the most serious circumstances. The least visited, least protected of the ruins in the monument, it had survived because it was inaccessible. Prior to MISSION 66, few visitors made it to the site, and occasional patrols, signs, and a register constituted the NPS presence. But the road-building program brought greater numbers of people to the vicinity of Inscription House. One of the major roads built on the reservation passed by Inscription House Trading Post on its way to Page. As travel increased in this remote area, many more potential visitors were in the proximity of Inscription House. The limited protective measures of the past became inadequate.

For the monument staff, there were problems of adjustment. During the early 1960s, there had been almost a complete turnover of park personnel. Many of the people who worked at Navajo before the MISSION 66 development had chosen the place precisely because it was remote. The changes made it less appealing. Following the departure of Superintendent Art White in March 1965, the last of the original generation made plans to leave the park. From White to Bud Martin to Robert Holden, all expressed a measure of sadness about the changes they recognized as imminent. [17] Nevertheless, their replacements had to learn to manage at an entirely new level of responsibility and accountability.

But as the impact of visitation and the leveling off of funding hit simultaneously, the park staff was left to fend for itself. Park personnel decided that curtailing services, particularly at Inscription House, was the best response to the changes they faced. The reports of patrols throughout 1966-67 showed that conditions at the site were rapidly worsening. Self-guiding trail markers had been uprooted and tossed aside, picnic fires had been built, vandals had rolled large boulders through the protective fence, and a number of the prehistoric ceiling beams were used for campfire fuel.

The initial response of the NPS reflected a desire to keep the ruin open to visitors. In an effort to avoid more depredation, the NPS removed a number of the signs and roadside guide posts announcing the site. In essence, the Park Service sought to keep the ruin open by increasing the degree of difficulty associated with traveling there. Officials initially hoped that this would keep visitation from rising. To prevent visitors from strewing garbage around the area, the Park Service added a picnic table. But such measures presumed that outsiders were responsible for the depredations. This approach did not take the culpability of local people into account. Damage to the site suggested that more comprehensive measures would be necessary.

Late in July of 1968, park staff made a crucial decision. As of August 1, Inscription House ruin would no longer be open to the public. Two factors necessitated the closing. The cancellation of the ruins stabilization program and the lack of workpower to do an adequate job for such a fragile ruin made visitation impossible. Remaining signs guiding the way to Inscription House were removed, as the Park Service decided that the merits of visitation to this outpost of the system were less important than providing adequate protection for a fragile and damaged prehistoric site. Rather than offer the twin benefits of increased popularity and greater enjoyment and understanding for visitors to Inscription House, increased access that resulted from paved roads led to exponentially greater impact on delicate resources. [18]

Inscription House was not the only portion of the monument affected by these changes. In the winter of 1968-69, Superintendent Binnewies announced that during the winter, the monument would offer reduced operations, services, and hours. Even after the completion of the approach road, visitation decreased dramatically in the winters. Pack trips to Keet Seel were impossible because of bad weather, and even Betatakin was hard to reach. Curtailed services saved money, and less contact with the public allowed more time for stabilization, repair, and other maintenance activities. [19]

The problems at Inscription House compounded the lack of funding for park programs. Since the turn of the century, erosion had threatened cultural resources along the wash. The bottom of the canyon was permeable, which meant that any standing puddle of water eventually seeped to the level of the arroyo and undercut the surface. Eventually this caused the surface to collapse, widening the existing arroyo and making greater erosion a certainty. By the middle of the 1960s, a number of archeologists had commented on the problem, but little had been done. In 1968, Archeologist Albert Ward, who worked there with George J. Gumerman in 1966, pushed for action. By the early 1970s, work was again underway at Inscription House. [20]

New patterns of administration also followed the approach road to Navajo National Monument. One primary change was the transfer of responsibility for Rainbow Bridge National Monument to the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area in 1964. Since 1909, Rainbow Bridge had been the responsibility of the custodian or superintendent of Navajo National Monument. This resulted from John Wetherill's position as the ostensible "discoverer" of both places. As an inveterate traveler and the sole outfitter in the region, he was an excellent choice. Until the 1930s, few people visited either Navajo or Rainbow Bridge without John Wetherill. But after the construction of the hogans for visitors at Shonto, Wetherill's control ended. In effect, Shonto opened the monument to others, limiting Wetherill's effectiveness as a custodian of two places. But because of the historical precedents, Rainbow Bridge remained under the jurisdiction of Navajo. Custodians and superintendents from James W. Brewer to Art White and their rangers made a semi-annual trip to Rainbow Bridge.

Most of the time their trip was an overnight stay, during which they performed rudimentary maintenance. Most visits consisted of some minor trail work and replacement of the visitors' register with a new one. Visitation remained low; in 1952, 552 people visited the bridge, 394 of whom came by boat, 124 by horse, and 34 on foot. [21] Without resources and labor, the position of Rainbow Bridge was even worse than that of Navajo. Only its remote location protected it from depredation and misuse.

But changes in the demands on the park system and the response of Congress and Park Service made the existing system impractical. Along with an aggressive program to dam western rivers, the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area was authorized in 1958. The construction of the dam led to the creation of a large recreational lake. The new administrative entity, Glen Canyon NRA, had its own headquarters, superintendent, and staff, all of which were closer to Rainbow Bridge than Navajo.

Rainbow Bridge was also part of a number of proposals to include it in a national park that would encompass a large part of the area. In support of this project, Secretary of the Interior Stewart L. Udall and his entourage visited Rainbow Bridge. The group came in a helicopter, offering a spectacular view of the bridge and the surrounding country. Rainbow Bridge had become a constant issue. Navajo lacked the resources to adequately administer another monument, and the same forces that spurred changes at other remote parks affected Rainbow Bridge. Clearly something had to be done. A change in responsibility seemed imminent. [22]

The point was driven home to the staff at Navajo in a dramatic fashion. During one inspection trip in the early 1960s, Art White and Bud Martin went beyond the bridge and met a crew from Glen Canyon NRA there to sink anchors for a floating marina on the new lake. The water level had not yet risen, yet there was a symbolic quality to this figurative moment of transfer. "If it's going to have water under it," Martin recalled White opining, "it might as well be managed by the boating rangers." Later, at a dedication for Rainbow Bridge, Mike's Boy, who took the Cummings party in 1909, was brought back to the bridge. Old and frail, he had to be carried in. It was emotional moment that spanned six decades. [23]

Another administrative innovation of the era was initiation of the Navajo Lands Group, a support entity for the parks in Navajoland, in 1968. During the 1960s, the Park Service sought to link numerous small areas in administrative groupings that centralized some responsibilities and added an additional layer of management between individual parks and the regional. Following a concept first developed by Frank Pinkley with the Southwestern National Monuments group and followed with a similar group in the Southeast headed by Herbert Kahler, the Navajo Lands Group was designed to provide archeological, interpretive, and maintenance support for the parks in and near the Navajo reservation. Included in the group were Navajo, Canyon de Chelly, Chaco Canyon, El Morro, Hubbell Trading Post, and other areas. John Cook, a former ranger at Navajo and superintendent at Canyon de Chelly, became the first general superintendent of the group; Art White succeeded Cook. Charles B. Voll recalled that he "presided over the demise" of the group in the 1980s. Each of the general superintendents had vast experience with the Navajo Nation, and provided strong leadership. Located in Chinle, Arizona, from 1967 to 1970, and then moved to Farmington, New Mexico, the Navajo Lands Group augmented the regular budget of park areas by pooling resources for joint administration of many of the functions of the parks in the region. It centralized skilled people in a number of specialized fields, making these resources available to more than one park or monument. [24]

In its fourteen years of existence, the Navajo Lands Group provided a range of services to a number of park areas. Because most of the parks in the region had small staffs, the Navajo Lands Group developed specialized functions that parks could not fulfill. For Navajo National Monument, archeological stabilization programs, for many years headed by Charlie Voll, provided essential service. The group also had equipment for use in a range of projects. It also provided periodic inspections of the various parks and analysis of situations.

One of these inspections in 1969 led to the development of new administrative practices at the monument. In December 1969, an appraisal team headed by Charlie Voll and including John Cook, Richard B. Hardin, Albert Schroeder, and Rodney E. Collins visited the monument. While generally impressed with the condition of the monument, they recognized a number of problems. In the view of the team, the park was "misstaffed." Navajo had too many staff members with high General Schedule (GS) ratings, and an insufficient number to perform technical and non-professional duties. The need for a "competent" administrative assistant was also apparent. At the time of the visit, the superintendent handled much of the routine paperwork that could have been done by a lower grade employee. The master plan for the monument was outdated, while public relations were "just adequate." Although the team did not perceive these problems as insurmountable, they suggested ways to rectify the situation. [25]

The appraisal team had recognized major problems associated with the rapid transformation of the monument. As a result of the approach road and the MISSION 66 development, Navajo had become an easily reached modern park area. The new responsibilities associated with more comprehensive management altered the pattern of staff activities. There were many more clerical-type functions that had to be accomplished, and most of the personnel at the monument were rangers with a penchant for the outdoors. Clearly a modern monument required more attention to administrative detail. A superintendent could no longer mimic Art White's tactic of making noises into the telephone receiver to convince superiors that there was so much static on the line that orders could not be understood. [26]

In part as a consequence of the presence of the Navajo Lands Group, a more comprehensive planning process emerged. With guidance from Farmington, the maintenance staff at the monument learned to handle minor ruins rehabilitation. Navajo National Monument also received the kind of planning documents that became the basis for growth in the park system. A backcountry management plan for the monument was approved in 1974, followed by a statement for management the following year. Navajo developed the infrastructure and support typical of park areas.

Despite the many advantages it offered, the Navajo Lands Group had inherent limitations. If fully implemented, it required major changes in the structural management of park areas. It created a level of management between a park and the regional office, and sometimes it seemed to park officials that the Regional Director never heard their thoughts. Some park superintendents resisted the program, and as long as the regional director supported the idea, it worked well. If he did not, the program floundered, as superintendents tried to circumvent it by taking their issues directly to the regional office. One former general superintendent recalled that the weakest superintendents, the ones perceived as not doing their job, resisted the group most vehemently. Under the administrations of regional directors Frank F. Kowski and John Cook, the program fared well. Under others, it was not as successful. [27]

For Superintendent Frank Hastings, the group was a mixed blessing. The access to a support network was critical for Navajo. Hastings could summon a working maintenance specialist who understood how to get funding out of the regional office, an archeologist, an administrative officer, and a general superintendent who had some influence on local Navajos. "The Group did some really great things," Hastings remembered. But there were drawbacks. The administrative officer of NALA was an extremely important person to each of the parks in the group. Some administrative officers played favorites, capriciously advocating the programs of their friends regardless of merit or justification. The group meant more paperwork within a shorter time, as every piece of work had to be reviewed at the NALA level before it went to the regional office, and to Hastings it sometimes seemed an indirect way to address issues. [28]

Navajo returned to direct relations with the Southwest Regional Office following the termination of the Navajo Lands Group in 1982. This gave the monument a kind of parity with other parks in the Southwest Region. No longer did Farmington filter the needs of the monument. Superintendents could present their case directly to the regional office. But conversely, Navajo and the other parks in the group lost much of their infrastructural support. Again they had to provide all their own services, a strain on the budget that caused much duplication from park to park.

Early in its tenure, Navajo superintendent Bill Binnewies offered a fitting epitaph for the Navajo Lands Group. It offered a genuine benefit, he remarked, for it absorbed a significant portion of the administrative workload as well as the management of maintenance of the ruins and helped address any emergency situations that occurred at the park. This allowed a park with a small staff to concentrate on its visitor service. Subsequent superintendents agreed, and a close relationship with Navajo National Monument was the rule throughout the existence of the Navajo Lands Group. [29]

New management studies in the mid-1970s showed that the monument had a number of administrative issues that still needed resolution. The constituency of Navajo National Monument had changed significantly since the completion of the approach road. Not only did more people come to the visitor center, even the small percentage of those that visited Betatakin or Keet Seel represented an exponential increase in the number of people who used the backcountry at Navajo. By the mid-1970s, even more visitors sought the experience. Park officials needed a strategy to assess and manage the increased impact.

The formalization of restrictions on trips to Betatakin and Keet Seel followed. A ceiling of 20,400 visitors per annum was established for Betatakin ruin. These were to be divided into groups of twenty, of which no more than one group would be allowed into the ruin each hour. This effort was designed to mitigate both the ecological and psychological carrying capacity of the ruin--the tolerance of people for people--and help keep the feeling of solitude that early visitors to the canyon expressed. [30]

At Keet Seel, there were similar problems. In 1972, 1,404 people visited the backcountry ruin, and officials expected that had not weather and water conditions held visitation to artificially low levels, the total would have been much higher. But Keet Seel was a fragile, unique place, much of which remained in pristine condition. Stabilizing it for larger numbers of visitors meant compromising its character to promote visitation. Park Service officials determined that the visitation total must not exceed the carrying capacity of the ruin. A firm limit of 1,500 per annum, divided up as fifteen per day, was instituted.

Reservation systems seemed the best solution to the problems posed by limits on visitation. For Keet Seel, prenumbered permits were issued on a first-come, first-served basis until 4:30 P.M. the day prior to departure. Any combination of horse riders and hikers was acceptable, but the limit was firm. For Betatakin, a limit of six tours of up to twenty visitors per instance during the summers became the norm. In spring and fall, the number of trips was reduced to four. But because of the frequency of tours during the summer, it was easier to accommodate those who wanted to go to Betatakin. They could generally get a travel permit on the day of their departure. [31]

Even more telling, Navajo remained anomalous among park areas because of the lack of the Park Service administrative control over the land on which facilities were located. In the 1970s, the move to charge entrance fees at all park areas gained momentum. In 1978, every unit in the system was surveyed. Navajo could not charge, Superintendent Hastings insisted, for the Park Service did not own the land on which the visitor center stood, had no arrangement with the Navajo Nation that would allow the agency to charge a fee, and could not enforce its rules as long as area Navajos used the road to the visitor center as a thruway. At the dawn of the 1980s, when Secretary of the Interior James Watt sought to put the park system on a paying basis, the inherent restrictions on Navajo moved it further away from the administrative focus of the Department of the Interior. [32]

By the early 1980s, the management problems of the monument had become consistent. The lease of the land on which the development stood remained a leading concern for park staff, growing numbers of visitors sought to experience the monument, and some management and interpretation programs had become dated. The slide and tape presentation needed improvement, for both the materials and the content were lacking. But as Dan Murphy, writer/editor for the Division of Interpretation and Visitor Services of the Southwest Region, noted, the hike to Keet Seel was "one of the best reasons for the existence of the [Park] Service." [33]

Management style at the monument also underwent a transformation. Since the arrival of James L. Brewer in 1939, Navajo had been administered by a generation of "old-style" Park Service men. These people were a unique breed. They had grown up with the agency, shaped by the difficulties inherent in the management of parks far from the mainstream. What characterized this group was a commitment to service and a lack of a sense of boundaries. Park people of this generation were Park Service through and through. The Park Service was a way of life that extended beyond the work day and in some circumstances beyond park boundaries. [34]

Frank Hastings, superintendent of the monument from 1972 to 1980, fit this mold. Under Hastings, Navajo became a self-motivated world where you did what it took. Nor was service limited to the park itself and visitors. The Informal Navajo Assistance program, as Hastings referred to it, continued. It included pulling pickups out of the sand or snow, donations of food during periods of heavy snow, and a system of support for individuals or families that needed care. In some instances, families stayed with members of the monument staff during difficult times. [35]

This ethic was communicated to everyone on the staff. "If a Navajo came up to the monument and said: `stuck down the road,' remembered ranger John Loliet, "we'd go and pull 'em out--no cost." Staff members did what each job required, often without noticing if they worked beyond quitting time or on activities that might not technically have been construed as park business. [36]

Nor was Hastings' approach new. For Brewer, John Aubuchon, Foy Young, Art White, Bill Binnewies, and others, the park was much more than a job. It and its relationship to the people of the region was an expression of themselves. In many instances, the informal relationships improved the status of the park in the region. Local people felt close ties to the monument, promoting interdependence in a park that needed its neighbors.

But by the 1980s, the old-style Park Service was becoming a memory. The insistence of upper echelon officials that park employees had to be protected against uninsured injury, compounded by the need for protection from liability for off-hours use of federal property, led to more stringent reporting. Rather than work "off the clock," as NPS people referred to the practice, supervisors insisted that rangers and other employees clock in their overtime. Parks with small budgets--such as Navajo--had to discourage employees from recording extra hours. There was no way to compensate them, but if they did not report hours worked, they left themselves uninsured and open to sanction if something went awry. The informal relationships of the era before 1980 had to become more formalized. Significant changes in the way park employees worked and ultimately in how they felt about the park system followed.

The 1980s were not an easy decade for the Park Service. Until the ascent of Russell Dickenson in 1980, the Park Service had suffered under nearly a decade of short-term directors. Its strong historic leadership seemed to have disappeared. Like much of the federal bureaucracy, the Park Service was full. Many people in their forties and fifties had reached positions of leadership at mid-career. But those who followed them, including many of the rank and file rangers, had little opportunity for upward mobility. Attrition in the NPS grew, as talented people left the agency for other opportunities. [37]

At Navajo, a new superintendent helped to smooth the move to the modern agency ideal. In 1980, Stephen T. Miller arrived at Navajo as Hastings' replacement. He brought a style of management suited to the 1980s. Miller managed in a more aggressive, more comprehensive manner than his predecessors, instituting the values of the new Park Service. Yet he was extremely popular with his staff, and was regarded as the "best superintendent [one could] ever work for." Miller accelerated the pace of activities at the monument, successfully delegated responsibility to his staff, kept on top of many topics, and cared for individual employees. Considered patient and fair by his staff and his superiors, Miller received high marks. Miller also worked to make Navajo more inclusive. He appointed John Laughter, one of the many Laughters who worked at the park, as maintenance foreman. Laughter was the first Navajo to become the head of a department at Navajo National Monument. It was a moment of pride for Navajo people in the region, and it accentuated the strong ties that followed the Memorandum of Agreement. Communication among the staff was good during Miller's tenure, and morale remained high. [38]

After a six-year stint, Miller was succeeded by Clarence N. Gorman, the first Navajo superintendent at Navajo National Monument. Gorman was a veteran of more than twenty years in the Park Service. He had begun as a seasonal ranger at Canyon de Chelly National Monument after serving in the Korean Conflict and attending Arizona State College in Flagstaff. He spent the summer of 1964 at Navajo National Monument as a seasonal, and progressed up the NPS ladder until he became superintendent of the monument. A native of Chinle, about sixty miles from the monument, Gorman's appointment was something of a homecoming. [39]

For area Navajos, Gorman's appointment was a milestone. "It's good to have a superintendent who speaks Navajo," remarked Bob Black, the most senior of the retired park employees in the region, and others concurred. Despite designation as a prehistoric site, Navajo National Monument had long addressed Navajo themes and issues in interpretation. Since the 1950s, individual Navajos had been interpreters at the monument. A number of seasonal interpretive rangers had been Navajo, and after Gorman became superintendent, emphasis on Navajo culture became stronger. In addition, the park became even more deeply entwined in the local community. Gorman and John Laughter attended local chapter meetings as representatives of the park and became a presence in local and regional tribal activities. Gorman served as Navajo-speaking coordinator for other park superintendents in Navajoland. He contributed to making the Park Service presence more visible to Navajo people in the area. [40]

As the region became more interdependent, the impact of the monument grew. The modern road added measurably to the importance of the monument, as did the growing number of permanent and seasonal positions at the monument filled by Navajo people. The number of Navajos living in the vicinity of the park grew following completion of the road, for it became a magnet that provided a lifeline for people in the area. The increase in use was so dramatic that the NPS requested that chapter presidents in the area inform members that they too created an impact on the road and that their cooperation in the maintenance and care of the road would increase its longevity. [41]

With the growth in population, the visitor center parking area became a thruway. Numerous local Navajos passed through one section against the flow of traffic. They saw the road as a thoroughfare. The Park Service response was typical of professional traffic control managers. Speed bumps and curbed islands were installed, pedestrian crosswalks restriped, and more comprehensive directional signs were placed in the area. The result was a measure of compliance, but at the end of the 1980s, Superintendent Gorman envisioned another road constructed as a loop around the parking area to accommodate local Navajo needs. [42]

Under Gorman, the Park Service retained strong ties in the area. The monument continued to serve as a center for the region, a place for area Navajos to go to get their problem solved. With a Navajo as superintendent in addition to seven of the other ten permanent employees, the monument and the dollars it generated were an integral part of life in the vicinity.

In a major cultural and behavioral change, Navajo visitors to the monument became increasingly common in the 1980s. Despite cultural prohibitions that historically kept them away from Anasazi ruins and anything associated with death, more Navajos began to express curiosity about the ruins. Many were as interested in the interpretation of Navajo culture as in prehistory, and a number expressed appreciation at the interpretation as well as the number of Navajo faces in NPS uniforms. [43]

Managing each of the individual units of the monument posed unique problems. Located adjacent to the tract containing the Visitor Center, Betatakin's issues generally reflected access and visitation. The cross-canyon trail that had opened in 1963 had significant dangers. Winter moisture caused a consistent pattern of rockfall just above the half-tunnel on the trail. In 1978 and 1981, inspectors concurred with park officials that the overhang on the trail presented a significant hazard. Between March 18 and 25, 1982, a major fall occurred. As much as nine and one half tons of sandstone toppled on the trail, while more fell all the way to the canyon bottom. The pattern of falls indicated that the spring was the most likely time for such an occurrence, but the NPS could not afford to take any chances. The threat of injuries to visitors on the trail was real indeed.

The situation led to closure of the trail at the beginning of the 1982 visitation season. Charles B. Voll, the acting general superintendent of the Navajo Lands Group, and Superintendent Miller reviewed the findings of United States Geological Survey geologist Frank Osterwald and agreed that the trail could not be kept open. Repairing, securing, and reopening the trail required, in Voll's words, "a sizeable chunk of money," and the park had to explore other ways to get visitors to the canyon bottom. [44]

The Tsegi Point route was the logical alternative. The initial approach to the monument after the opening of the Shonto road, it had much to recommend it. Yet there were disadvantages. The departure point to the canyon bottom was a little more than one and one half miles from the visitor center, but it was not easily accessible. There was no auto road to Tsegi Point, nor any facilities at the departure point. Nor did the Park Service administer the land on that side of the rim. There were a number of fence gates that had to be opened and closed on the route. This made a difficult walk into one largely impossible for the average visitor. Most were not tuned to the cultural sensitivities on which they intruded. The closure of the cross-canyon trail represented a setback for access at Navajo National Monument.

To counter this setback, the Park Service took extreme measures. The Tsegi Point route was opened, with school busses employed to carry visitors the one and one-half miles to the point. The busses averaged only four miles to the gallon, making this an expensive way to convey visitors to the ruins trail. The safety of passengers in large awkward busses on a narrow trail was also questionable. The grade to the point was steep in numerous places, and the trail barely merited the label "road." Nor were bus gears and brakes designed for such conditions. While the bus trip to Tsegi Point eliminated the danger of falling rock, it had drawbacks of its own. [45]

The result was an effort to use the resources of the monument to make the Tsegi Point trail more accessible. In 1989, the park expanded the parking area for cars near the trailhead for Tsegi Point. While this made for a longer hike, it allowed for greater contact between interpretive rangers and the public. For the monument, the expanded parking area eliminated the high cost and questionable safety of busses on the narrow road.

By the late 1980s, guided walking trips had again become the primary means through which visitors reached Betatakin. Yet beginning in 1990 and continuing in 1991, budget limitations curtailed the number of tours to two a day. The monument simply did not have enough money to permit more. The implications for Navajo were vast. An evident decline in visitation numbers from 70,932 in 1989 to 64,275 in 1990 seemed to result from the inability of visitors to sign up for a tour on the following day. With only forty-eight people per day permitted into the canyon, the sign-up que for the tour always involved waiting. Campfire programs were another casualty. At the campfire circle, one of the essential Park Service interpretation activities took place. At Navajo in the late 1980s, the stones remained cold to the touch. "It's hurting us," remarked Superintendent Gorman as he pondered the funding situation. [46]

At Betatakin itself, the overall conditions remained good. The closing of the cross-canyon trail limited visitation even further below the limit established by the NPS. While curtailing the use portion of the Park Service mandate, this situation had a healthy positive influence on the preservation side of the equation. Fewer people meant a generally smaller adverse impact, but a number of ecological issues related to use existed. Park Service inspectors recognized a need for a use plan that balanced visitor safety and use.

By the early 1990s, the two principal problems of the ruin had been with the monument for a long time. As elsewhere in the region, erosion of the canyon bottom posed a primary threat. Widening of the creek at Betatakin similar to that at either Keet Seel or Inscription House could have disastrous consequences. While the ruin remained in very good condition, the threat of falling sandstone presented the possibility of damage to the ruin and harm to unfortunate visitors. Both of these perennial problems required vigilance and constant attention.

Managing the two outliers posed additional problems. Despite its closing, Inscription House was the most vulnerable to unauthorized visitation, the elements, and ecological conditions. Without a constant NPS presence and easily accessible from Arizona Highway 98, the ruin suffered from a range of depredations. Some were typical vandalism: name-scratching, destruction of fences, and general callous behavior directed at the site. Others were long-term management concerns, such as the continual erosion of the wash in Nitsin Canyon that began to encroach upon the approach to the fragile adobe-construction ruin and the lack of a consistent source of funds for stabilization in the aftermath of the demise of the Navajo Lands Group. [47]

Efforts to address such problems dated from before 1968. The closure of the ruin to the public resulted from the inability to protect Inscription House from these two threats. After 1968, attempts to add land for a contact station began. In 1976, Archeologist David J. Breternitz received a contract for stabilization and excavation.

The project led to recognition of the need for a ranger station at Inscription House, and in 1978, the Park Service made a serious effort to acquire additional land. Officials planned to re-open the area to the public in 1979 on a reservations-only basis with a live-in seasonal ranger in the new contact station. An Environmental Assessment was completed, and permission from the landowner, a Navajo named Frank Reed, was secured. The Advisory Council on Historic Preservation accepted the assessment of the Park Service that no adverse impact would occur as a result of the project, but Brewster Lindner of the NPS pointed out that the people who made the lease agreement had no authority to do so. In addition, the lease did not include enough land for sewage and water, and local people regarded the construction of a permanent ranger station as a threat and an intrusion. Flawed in this fashion, the proposal died. The structure was not built and the plan was never implemented.

At the dawn of the 1990s, park staff recognized the precarious position of the 40-acre Inscription House tract. In 1988, the Park Service removed the last vestiges of its presence at Inscription House. Interpretation signs, the visitor log, and other basic features were collected and brought back to the Betatakin unit. Even logs wired in place as a bridge across the ever-deepening wash were taken away. Inscription House had no real protection but evidence of frequent trespassing was clear. One off-duty ranger recounted meeting people on the trail into the ruin, and on occasion running into people inside the Park Service fence there. Vandalism was endemic, and the rapid rate of erosion compounded other problems. The only money for stabilization came from the regional office special projects fund, but there were no guarantees that the support would be annual. Inscription House reflected an aggravated version of the situation of most detached units in the park system. [48]

Facing many similar problems, Keet Seel fared better. Erosion of the Keet Seel Wash presented a major threat. It had doubled in size and depth since 1940, and recent fences put up have slumped into the wash. The 160-acre section was victim to the land practices of the people around it. Livestock grazing continued nearby, exacerbating existing erosion and possibly leading to changes in the micro-environment. Yet there were positive dimensions to the situation at Keet Seel. The installation of a ranger at the site during the summer that began in the early 1960s curbed vandalism. [49] In no small part as a result, the ruin was the best preserved of the three major ones in the monument, and at the beginning of the 1990s, few threats to the ruin itself were evident. Besides erosion, only the lack of funds to keep a ranger in the canyon threatened Keet Seel ruin.

The modern era had also transformed interpretation at the monument. Despite its archeological mandate, the park had a long history of interpreting both the prehistoric and historic pasts of the western reservation area. Both Anasazi and Navajo culture had long been represented in the programs of the monument. John Wetherill began the process, and sympathetic superintendents and rangers from Art White to Clarence Gorman helped make a place for Navajo culture in the interpretation plan of the monument. The location of the monument in the heart of the reservation, the number of Navajo laborers who worked there, and such obvious Navajo features as the construction of the pink hogan reinforced the two-pronged approach. In the 1960s, the exhibit plan for the visitor center codified this dual perspective when it emphasized both Navajo and Pueblo themes for the monument.

For visitors this added measurably to their experience. The name of the monument piqued their interest in the Navajo as well as the Anasazi. Summer crafts programs, exhibits, interpretation, and the Navajo-owned and managed gift shop all contributed to furthering that interest. Visitors could find a multi-layered cultural experience when they visited Navajo.

Individual Navajos in interpretation found themselves in a choice position to convey their culture to visitors--if they wanted to. According to former park rangers, interpretation required unusual personality characteristics for Navajo people. To interpret, an outgoing nature and an outward enthusiasm generally inconsistent with Navajo culture and uncommon among Navajos was essential. Some younger Navajos possessed these traits; Shonto (Wilson) Begay, a fixture in interpretation early in the 1980s, "had people eating out of his hand," one of his peers recalled. He could convey information to visitors in a fashion to which Anglos responded. Many others had difficulty overcoming this cultural barrier. [50]

Yet some features of the interpretation scheme at Navajo were rare in the modern park system. Navajo offered old-style NPS interpretation in the modern era. The guided tours essential for the protection of the ruins had been the signatory practice of Frank Pinkley's Southwestern National Monuments group in the 1930s. By the mid-1960s, most park areas had given it up as impractical and too expensive in the face of large numbers of visitors. But the unique circumstances at Navajo rendered strictly economic and numerical considerations moot. As a result of the fragility of the resource and its distance from visitor services, in the 1990s, Navajo maintained a guided tours-only policy reminiscent of the early days of the agency.

In the early 1990s, Navajo National Monument remained a place in transition. In many ways, it had became a modern park area staffed by a modern professional staff. In others, it remained an outlier, a place out of the mainstream, faced with local concerns and needs. Its position within the Southwest Region enhanced its paradoxical state. Navajo fared well under the Navajo Lands Group, but less well after the return of direct Southwest Regional Office management. [51] In the group, the weaknesses of a small park were protected. As one of many parks in the region, the park lacked the obvious institutional support provided by the group as well as the commonality of interests with other parks that the group structure provided. As money within the system became less available and the demands on the monument increased, the paradox of modernity and remote character continued to plague the monument.

Yet this situation at the monument allowed for a closer relationship to the people of the immediate area than was possible at most park areas. "Sometimes we did not feel there was a boundary" between the park and the people around it, one park ranger recalled, and his peers supported this point of view. [52] Navajo National Monument was in a unique position. An important piece of the local economy, it was as dependent on the Navajo people in the vicinity as they were on it. This interdependence meant that a complicated relationship critical to the park had to be fostered, nurtured, and preserved. While increasing integration of Navajos in leadership roles at the monument was an important step, the situation always remained tenuous, dependent on cross-cultural perceptions.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

nava/adhi/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006