|

Navajo

A Place and Its People An Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER VI:

PARTNERS IN THE PARK: RELATIONS WITH THE NAVAJO

The Memorandum of Agreement at Navajo National Monument formalized a longstanding pattern of interaction between the park and the people of the Shonto region. After the beginning of development at the park and the change in the Navajo economy as a result of the stock reduction programs of the 1930s, the ties between area Navajos and the Park Service became stronger. A symbiotic relationship developed, in which Navajos gained economically from the park, which in turned received the benefits of Navajo labor as well as the ability to offer visitors a picture of Navajo life.

The ties long preceded the Memorandum of Agreement signed in 1962. John and Louisa Wade Wetherill had initiated the close relationship. As traders in Navajoland, they earned the trust of the people of the area. Louisa Wade Wetherill became particularly interested in the Navajo people and their culture. Fluent in their language, she became an expert on Navajo culture. In the living room of the Wetherill trading post in Kayenta, John Wetherill discussed the prehistory of the Southwest, while Louisa Wade Wetherill held forth on the Navajo. Even her children knew not to contradict her on this subject. [1]

After the Park Service began full-time administration of the monument, there were significant attempts to portray Navajo life and culture at the monument. Exhibits reflecting Navajo themes were common, inspiring positive responses from visitors. In 1952, Superintendent John J. Aubuchon reported that the Navajo exhibit in the corner of the contact station was extremely popular. John Cook recalled an emphasis on Navajos in the interpretation programs of the monument in the late 1950s and early 1960s, something augmented by the presence of Navajo seasonal employees and rangers. Trained in anthropology, Art White was knowledgeable in the ways of the Navajo people. His tenure at the monument allowed him to pursue this interest. [2]

The Park Service also followed liberal policies towards the Navajo. Long before the Native American Religious Freedom Act of 1977 made the practice into law, Navajo medicine men came into the monument to collect plants for healing and ceremonial use. The Park Service allowed them access as a courtesy, with superintendents from James W. Brewer to Frank Hastings acknowledging the importance of religious practices to area people. This kind of cooperative arrangement served as a model for later efforts between the Park Service and Native Americans at other park areas. [3]

By 1962, a pattern of inclusion at the monument had developed. The Navajo people in the vicinity of the monument had become partners in the park. They made up a significant portion of its labor force, recognized the park as a source of economic support, and generally and loosely supported its objectives. The monument and its staff were able to reciprocate by offering the accouterments of modern society to the people of the region. Bob Black used the road grader to grade the road to Shonto on a regular basis; in the winter, the park's snowplow could be found plowing the way to various hogans in the region. In reality, Navajo National Monument was three small islands among the Navajo. In a harsh land, cooperation and adaptation assured the survival of all. [4]

The Memorandum of Agreement created a formal structure that defined the responsibilities of both the Park Service and the Navajo Nation. In exchange for the use of 240 acres of Navajo land on the rim of Betatakin Canyon, the Navajo Nation acquired specific privileges at the monument. One of the most important of these was control of an approximately 450-square foot area in which crafts, pottery, and other gift items could be sold. This assured an economic relationship between the park and the Navajo that transcended the employer-employee pattern typical before the agreement. Navajos developed a proprietary interest in the park.

As a result of cultural and social changes in the U.S., the NPS had to address the needs of the Navajo Nation in a more comprehensive fashion after the signing of the agreement. At the establishment of the monument in 1909, individual Navajos had little say about the disposition of the area. After the development of the tribal council governing structure in the 1920s, Navajos gained active and outspoken leadership that defended their interests. In the aftermath of the civil rights movement, Navajo people became willing to assert their rights in a manner never previously associated with them. In the late 1960s, the Navajo tribe changed their official designation to "Navajo Nation" to reflect the unique status of American Indians in the U.S. This nationalism emerged as an effort by the Navajo people to gain greater control over their social, economic, and political lives and culminated in the initial election of Peter McDonald as tribal council chairman in 1970. [5] The result of this empowerment challenged the Park Service in new ways.

Park officials had to learn a new pattern of sensitivity toward Navajo needs. In some instances, they found the changes frustrating, for accommodating people with a distinctly different value system was not easy. The level of consensus among the Navajo necessary to achieve NPS goals was often elusive, but Park Service officials with a great deal of experience in the region such as John Cook, former chief ranger of Navajo National Monument, helped smooth the transition. In one instance in 1967, NPS officials at the regional and national levels reviewed the possibility of condemnation as a means to land acquisition. Cook, then superintendent at Canyon de Chelly, pointed out that "the bad associated with condemnation will be far reaching." [6] This measure of understanding and respect for the Navajo perspective was new in government-Indian relations. The NPS slowly learned to address the needs of the Navajo Nation within a more equitable and less paternal system than had existed previously.

The transformation of the Navajo labor force at the monument reflected the changing relationships. Because the monument had so little funding, seasonal labor was intermittent before the 1930s. Most of the Navajos who worked at the monument before the 1930s were associated with the various archeological expeditions. The New Deal provided money for the first seasonal laborers, among them Bob Black, who began in a seasonal capacity in 1935 and remained at the park for thirty-one years. In 1948, Seth Bigman, one of the many Navajo who fought in the Second World War, became the first Navajo seasonal ranger at the monument. He served two years. Bigman was followed by Hubert Laughter, another Navajo war veteran whom Bob Black recruited for the monument. Laughter also served as an interpretive ranger at the monument during his three-year stay. [7]

The Navajos who worked at the monument all had close ties to the Shonto area and strong cultural reasons for staying close to home. Generations apart, their life stories had many parallels. A veteran of World War II, Hubert Laughter returned to the western reservation with a Purple Heart and the desire to make a life. He found a job in Winslow, Arizona, as an airplane mechanic, but because his wife was from a very traditional Navajo family that did not want the couple to leave the reservation, he stayed in the Shonto area. The job at the park seemed a solution to the problem of being caught between two worlds. It offered him economic opportunity at home--although his family long debated whether he should take the job at the park. [8]

A generation later, Delbert Smallcanyon followed a similar pattern. He first came to the monument in 1968 as a stone mason on the cross-canyon trail. Born around 1920 in the Navajo Mountain area, he tended sheep for his family well into adulthood. He first left the reservation to work for the railroad during the Second World War, and later followed it from place to place, working in Montana, Salt Lake City, Chicago, and elsewhere in the West. This pattern of seasonal movement typified the experience of many Navajos of his generation. He left his home only because his family needed the income from his labor. He did not enjoy the work, its pressures, nor the places he went. It was his duty. His paychecks became the means to sustain his family after the local subsistence economy ceased to provide sustenance.

A permanent job close to home seemed a wonderful opportunity that allowed him to maintain a traditional lifestyle. Each day he came over from Navajo Mountain to the park, returning after a full day's work. The job at the park allowed him to remain in his homeland, live a traditional lifestyle and support his family--economically sustained by his job at the park. [9]

With the signing of the Memorandum of Agreement and the expansion of the staff at the monument, there was greater opportunity for Navajos who sought work at the park. They soon recognized that permanent ranger positions were generally filled by career Park Service employees. This prompted a number of younger Navajos to enter the Park Service, among them Clarence N. Gorman. But maintenance positions were available for local people, as were a range of seasonal positions. By the middle of the 1960s, the maintenance staff was exclusively Navajo except for the maintenance supervisor. In the middle of the 1980s, John Laughter took over this position, the first Navajo in a permanent supervisory capacity at the monument. This also cemented the Navajo character of the maintenance staff. [10]

John Laughter's supervisory position was an important transition for the monument. Prior to coming to the park, he worked for a general contractor as a heavy equipment operator. In 1974, Frank Hastings hired him to work on the maintenance crew. After a decade in maintenance, during which he took all the Park Service training courses he could, Laughter was appointed foreman. As the first Navajo in a position of leadership at the monument, Laughter expressed a sense of pride in his work that was reflected in the work of his staff.

Navajos of different generations appeared to have a different view of the park and its workings. In the 1980s and 1990s, older Navajos expressed gratitude for having jobs at the park. The combination of proximity to their homes and good pay made the positions very desirable. They did their work well, seemingly unaware of the context in which they labored. Younger Navajos understood the mission of the park more clearly than did their elders, and they recognized how important the monument was to the economy of the entire western reservation. They could see the many ramifications of its economy on the lives of themselves and their families. [11]

Yet until the middle of the 1980s, structural problems with the distribution of employment at Navajo National Monument remained. In 1982, five of the nine permanent employees at the monument were Navajo. Three Anglos worked at the park, along with one Hispano. Yet all of the Anglos and the Hispano had higher GS ranks than did the five Navajos, leaving a skewed structure that reflected the slow process of the changing patterns of leadership in the American and federal work forces. After John Laughter became maintenance supervisor and the subsequent appointment of Clarence Gorman as superintendent, the historic limitations ended. By 1990, the monument had eleven full- and part-time employees. Eight, including the superintendent, the head of maintenance, and the entire maintenance department, were Navajo. The park more accurately reflected the demography of the area. [12]

Changes in the demography of employment at the monument only reflected the changing cultural climate outside its boundaries. By the early 1970s, the western reservation had begun to undergo comprehensive transformation. The people of the region had a long and proud history. Navajos had begun to settle in the area in an effort to avoid the forced confinement at the Bosque Redondo near Fort Sumner in the 1860s. Fleeing the American military, they found the area around Navajo Mountain far enough from the reach of the cavalry. The result was a regional culture intentionally isolated from the encroaching industrial world and its material by-products, less receptive to Anglo-Americans than other parts of the reservation. Trading posts came later and were fewer and farther between on the western reservation. Nor was their influence as pervasive before the stock reductions of the 1930s. [13]

As late as the early 1970s, the western reservation seemed lost in time. Nearly a decade after paved roads crossed the region, the most common form of transportation for Navajo families in the area was the classic orange and green Studebaker horse-drawn wagon. Bill Binnewies recalled that during his tenure as superintendent of Navajo in the early 1970s, the pick-up truck era began in the Shonto vicinity. About the same time, Navajo families began to travel to other places, a practice uncommon prior to that time. Yet these symbols of greater exposure to the outside world were the harbinger of a revolution in lifestyle for the people of the western reservation. [14]

Before the Visitor Center and the paved approach road, park personnel and their neighbors had an interdependent relationship. The park was the long arm of an industrial society. Its needs were supplied from elsewhere. But in the remote backcountry of Arizona, the people who ran the park had to rely on their neighbors in many instances. Area Navajos could also benefit materially from their relationship with the park. Besides employment, the park could offer communications, transportation, support, and medical facilities unavailable to most of the people in the region. In addition, both the Park Service and the Navajo had to battle the often inclement climate of the area.

The interdependence produced a number of close personal relationships between park personnel and their neighbors. Neighbors and often friends, the staff and area Navajos looked out for each other. This solidified existing relationships in instances such as a major snowstorm in the late 1960s, when Superintendent Bill Binnewies left his home on horseback in thigh-deep snow, loaded with canned goods for the nearby Austin family. On the way, he met E. K. "Edd" Austin, Sr., the patriarch of the family, coming toward him with a side of beef in case the park was out of food. These concomitant gestures of personal concern suggested the feeling of community that transcended cultural and institutional lines at the monument. [15]

The empowerment of the Navajo began before the 1960s. By the late 1940s, Navajos in the vicinity of the monument had become avid workers in a range of programs. Wage scales had been standardized, and Navajo laborers were paid a sum equal to that of laborers in different parts of the country. In 1947, this rate of $1.15 per hour put laborers dangerously close to the hourly wage that could be factored out of the custodian's annual salary. Park Service standards for wages were set in Washington, D. C., and exceeded even the rates paid by the U.S. Indian Service. As park budgets were limited, the high cost of wages limited the number of workers and length of time for which they could be employed. [16]

Federal regulations and policy bound the department. Even in 1947, when discrimination in wages was the rule in the U.S., the Park Service insisted on paying its Navajo laborers the same rate as non-Indian workers. This practice, which clearly frustrated some who perceived that the standard wage on the reservation should be lower than elsewhere because of the large available pool of labor, was in part testimony to the commitment of the Park Service to support local constituencies. It was also part of the process of empowering the Navajo people, particularly in their own land. [17]

By the middle of the 1950s, the Navajo had taken a more aggressive approach towards activities on the Navajo reservation that did not use Navajo labor. Preferential hiring clauses were instituted, requiring that off-reservation construction companies employ Navajos. This attitude affected the Park Service as well. When looking for labor, the NPS was required to select a fixed percentage of Navajo workers. When they did not, even in exempted activities, there could be consequences. In 1958, Tribal Council member Paul Begay threatened to close down a stabilization project at Inscription House because it employed no Navajos. [18] The incident reflected a growing militancy among Navajos that came to the fore in the 1960s.

That decade saw the culmination of major changes in the cultural history of the U.S. The civil rights movement served as the starting point; the effort to achieve the attributes of citizenship for American blacks inspired a panoply of other reform-oriented activities. A student protest against the war in Vietnam was one major ramification. The emergence of Hispano, Indian, and other movements that sought to extend the advantages of the modern world to groups that previously had been left out was another. There was a growing sense of empowerment among these groups, most of whom had previously been relegated to peripheral positions in American life.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Navajo people began to exert influence on state and local government, education, and other institutions and processes that affected their lives. In Chinle and Window Rock, Navajos gained the majority on the school boards; in other places Navajos swarmed the polls, voting in unprecedented numbers. In southern Apache County, Anglos feared a Navajo majority and unsuccessfully sought a separate Navajo County. Despite these and other efforts to curb their growing power, Navajos showed that they were on the verge of becoming a force in regional politics.

Navajo politics were generally pragmatic and issue-oriented. Concerned with basic civil rights and economic and social issues, the Navajo people were generally far removed from the political radicalism most evident on college campuses and in the anti-war movement. Although the cultural revolution that swept the nation helped fuel a Navajo awakening, the Navajo themselves looked to solve the problems of their world. Despite the emergence of "red power" as a philosophy and the militance of Indian organizations such as AIM, the American Indian Movement, the Navajos remained largely apart from efforts to destroy the modern world and rebuild it anew.

Organizations such as AIM had a complicated impact on the Navajo. Some people embraced these empowerment movements wholeheartedly, defining themselves in opposition to mainstream American society. Many of the people who became enthusiastic about these changes were urban Navajos, who felt caught between both worlds, neither wholly Indian nor white. Others, predominantly more traditional Navajos such as many of the "longhairs" in the vicinity of the monument, were much more ambivalent toward radical Indians. Closer to traditional culture and the way of life expressed through it, they did not value recognition from the white world as much as the spirituality and sentience of the Navajo way. The more traditional Navajos were less tied to the Anglo world. As a result they felt less oppressed by it and had little need to express their anger towards it.

Within the Navajo Nation, empowerment led to the formation of numerous support organizations. Among these was a legal aid society called Dinebeiina Nahiilna Be Agaditahe (DNA), which was supposed to help poorer Navajos who had problems with the legal system. During Peter McDonald's first administration, DNA made impressive gains for Navajos, filing a class action suit against trading post operators seeking fairer trade practices and winning an affirmation of the right of individual Navajos to be exempt from state income tax on wages earned within the boundaries of the Navajo Nation. DNA had two tiers, one made up of lawyers--most of whom were not Navajos--and another of advocates, Navajos who could explain the legal system to other Navajos. In the climate of the 1960s and early 1970s, there was a powerful political dimension to the activities of DNA, and the organization was often embroiled in controversy. [19]

One DNA advocate, Golden Eagle, who had previously been known as Leroy Austin, brought the influence of the outside to the remote world of Navajo National Monument. A son of E. K. Austin, who ran the guided horse tours to Keet Seel, Leroy Austin had been away from the area for a long time. In an unusual series of events one summer weekend in 1973, he terrorized visitors and a ranger at Keet Seel, threatening them in an abusive manner while intoxicated. In the fashion of the time, he regarded the Park Service as an occupying power on Navajo land. In search of assistance, the park ranger left Keet Seel for headquarters. In the interim, the incident came to a tragic end when one of Leroy Austin's brothers shot and severely wounded him. But the incident itself revealed that with the access of the paved road came every attribute, good or bad, of modern society. [20]

The incident was more typical of the era than of relations between the park and its neighbors at Navajo National Monument. There was an extreme tone to the late 1960s and early 1970s, an all-or-nothing, for-or-against feeling that, at its most outlandish, suggested that the monument was a symbol of oppression. The instigator himself had become an outsider. He had not been back home for a long period prior to the incident and the prisms through which he viewed the relationships of Tsegi wash were more those of urban America than the Colorado Plateau. Yet influenced by the furor of the time, he expropriated the ideals of a social movement for individual purposes and seized on the NPS as a symbol of perceived oppression. Ironically, many of the Navajos of the Shonto area were appalled by his behavior.

No good resulted from such an incident, but it served to further enunciate that the remote character of the monument that insulated it for so long had ceased to exist. It also offered insight into the complicated web of relationships that predated the Memorandum of Agreement and that the agreement did not erase. Ultimately this culminated in threatening and violent expression in an era of emphasis on identity and fidelity to cultural ideals of mythic proportions.

There were other smaller incidents that reflected the changes in cultural attitude of the Navajo and caused the Park Service to be aware. In 1974, a medicine man display in the Visitor Center attracted negative attention. The collection, comprised of the parts of a Navajo medicine man's kit, had been purchased by the park from a Shonto man named Bert Barlow in 1971. This was a relatively frequent occurrence, as a similar purchase occurred from some unnamed Navajos the following May. An exhibit featuring these articles was displayed beginning in May 1971. In December 1973, a number of Navajos who claimed to be from the family to which the kit belonged came to the park and sought to buy it back. They returned on at least one other occasion, but never made contact with the superintendent. Yet the possession loomed as an issue. "It makes my heart sad to think of [the collection] imprisoned," one of the Navajo told a park technician. [21]

The response of the park was complicated. In the early 1970s, repatriation of Indian artifacts and remains had not yet become an issue. Recognizing the interdependence that characterized their existence, park officials knew that they had to proceed carefully. The artifacts had been purchased legitimately, park staff reasoned, and some had doubts about the people involved. Superintendent Hastings had "no inclination or authority to sell or give it back to these people because they only wish to resell it for a better price." The specter of DNA advocacy appeared, and Hastings feared pressure. Although no further developments occurred at that time, again the impact of the 1960s reached the park. [22]

But situations like the Golden Eagle incident were an extraordinary exception to the general pattern of relations between local Navajos and the park. The web of relationships created genuine economic, cultural, and personal interdependence, spawning close friendships among people of different cultural backgrounds. Park officials tried to be good neighbors, offering area Navajos as many of the benefits of the modern facilities as they could. These were both institutional and cultural. According to Bill Binnewies, individuals rather than a Park Service uniform made these relationships work. Park personnel who sought camaraderie and mutual respect made the NPS green a friendly sight for area Navajos. [23]

This closeness dated back to the days of Hosteen John Wetherill and was a characteristic feature of the people who worked at the monument. There had been what one former superintendent characterized as the "informal Navajo Assistance program," a comprehensive effort by the Park Service to be good neighbors. Art White made it a point to grade the road all the way to Shonto, clearing what had become a lifeline for the people of the vicinity. He also allowed Navajos to fill their fifty-five gallon water barrels at the park, loaned his neighbors tools, and generally worked to promote harmonious relations. Binneweis encouraged a young Navajo woman who worked as a seasonal ranger at the park to go back to school to get a teaching certificate. She became the first Navajo with credentials to teach in the Shonto district. Frank Hastings recalled pulling pick-ups out of sand and snow, feeding people in times of heavy snow, taking in local Navajos in need of temporary care, and serving as a communications center for the people of the region. [24]

Other kinds of ties bound the people of the park and their neighbors together. Bud Martin, P. J. Ryan, and other rangers developed an affinity with their Navajo neighbors based on the similarities in their personalities. Private people who enjoyed the solitude of the monument and did not particularly care for intrusions, the staff found that they had common ground with their Navajo neighbors. Ryan later remarked that he found the constant questioning of Navajos by the anthropologists to be an intrusion. On one occasion, he told a number of Navajo workers about an Irish folktale that equated the appearance of a raven overhead with impending death. When asked by anthropologists to recount their folklore, the Navajos who heard Ryan's story responded by repeating it as if it were a Navajo folktale. The anthropologists later asked Ryan if he had any more Irish stories for them. This comic incident underscored how close people of different backgrounds could become. Ryan's ability to communicate with Navajos and his respect for their privacy helped build a close relationship. [25]

The increase in the number of Navajos who worked at the park also contributed to the establishment of close ties. As the facilities at Navajo National Monument were built, the need for labor grew. Other activities that improved visitor service, such as the construction of the cross-canyon trail, brought more Navajos to the park. Some, such as Delbert Smallcanyon, began as temporary laborers and made careers out of working at the park. Park officials were pleased with the developments. At chapter meetings, they had supporting and explanatory voices, advocates with an investment in the park and its policies. [26]

A number of families were well represented at the monument. Bob Black was the patriarch of Navajo employees; his granddaughter Rose James worked at the monument in the 1980s and 1990s. Hubert, Floyd, Robert, and John Laughter all worked at the park, as did Seth and Akee Bigman. The Begishies were well represented among park employees. Many other relatives of these and other families also worked at the monument, adding a familial dimension to the workplace.

The park also broadened its base of visitors in the 1980s. For the first time, Navajos became frequent visitors to the park. Many had long shied away as a result of cultural taboos concerning Anasazi places, but as they became more exposed to Anglo ways of living, Navajos too came to visit. Clearly children were a major influence. Visitation by Navajos increased after the beginning of a Navajo Nation program to place teenagers in summer positions at the monument. The young people returned home and brought their parents back to visit with them. Even the most traditional Navajos who came to the park--those who refused to go to the ruins themselves--still walked the Sandal Trail to the Betatakin overlook. [27]

|

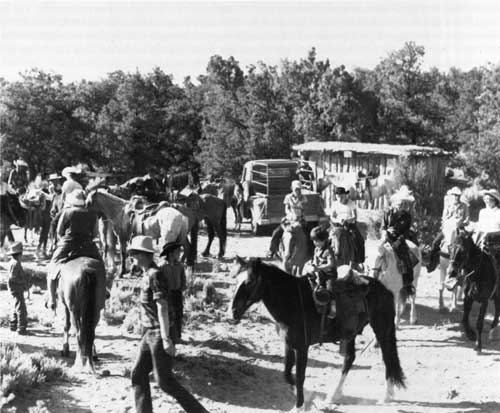

| Visitors load their horses for a trip to Keet Seel. |

In visitor service, area Navajos played an important role that resulted from the non-contiguous nature of the park. The trip from the visitor center to either Betatakin or Keet Seel ruin crossed Navajo land. Eight miles distant, Keet Seel was easier to reach by horse than foot. In 1952, area Navajos began to make horses available for guided tours to Keet Seel. Pipeline Begishie, the patriarch of a local family, organized the trips. Many of the people in the area allowed their horses to be used--for a fee--and Begishie or one of the others close by guided the trips. The fee was ten dollars per day for the guide and five dollars for each horse. The animals they used were big and strong, one observer recalled, and the trips had real appeal for visitors. [28]

The memorandum formalized the outfitting proces at the monument, requiring more than a verbal agreement and possibly precipitating a change in the vendor. One summer in the early 1960s, Pipeline Begishie decided that the horse trips were more trouble than they were worth. Some accounts suggest that one of Begishie's neighbors, E. K. Austin, bullied him into a cessation of his activity. Into this vacuum stepped Austin, who claimed the land through which the trips had to pass on the way to Tsegi Point and Keet Seel as his own. Much of the exchange between Begishie and Austin occurred without the knowledge of park personnel. Yet Austin stepped forward and claimed the right to offer services to Keet Seel. In exchange for the right of passage across Navajo lands, the Park Service agreed to let the Austin family offer guided horse trips to the outlying section.

E. K. Austin related a different version of the transfer. He claimed to have taken pack trips to the ruins since the days of John Wetherill. In his view, Begishie was an interloper, crossing on Austin's land. The monument was located in the district of the Shonto Chapter, but Austin was enrolled in the Kayenta chapter. He believed this accounted for Begishie's presence. The disagreement became serious in the early 1960s, and both Art White and his successor Jack Williams tried to mediate. They were unsuccessful, and both Austin and Begishie were called to Window Rock. There, Austin claimed, he was vindicated and offered the service that was rightly his.

Austin's privilege to offer horse trips was not exclusive, although he worked to make it a monopoly. As late as 1966, Jack Williams noted that Begishie's permit to carry people to Keet Seel was valid, but he would not do so as long as the Austins did. The transfer may have been done by force or by intimidation, but the result was the same. E. K. Austin had control of the horse trips to Keet Seel. [29]

This was a less than optimal arrangement for the Park Service. Since Stephen T. Mather's day, the agency prided itself on the sophisticated and comprehensive level of service that it could offer visitors. The Park Service built its national constituency by making affluent Americans comfortable in the national parks. MISSION 66 sought to broaden the appeal of the park system to the post-war traveling middle-class. It created facilities for auto travelers and their families, including accommodations, interpretation, and the range of other necessary accouterments. Generally the right to offer concessions in park areas were the subject of a bid process. The competition was fierce, and sometimes the profits were limited by NPS regulation. But under the strict control of the Park Service, service in the park system was generally first-rate. [30]

But the Park Service had little control over neighboring landholders who owned the land between the detached sections of Navajo National Monument. The superintendent and staff could only hope for the best. Service to visitors was spotty. In some cases the tours went well, but generally they did not. One staff member remembered the Austins as "good capitalists." They delivered people to and from Keet Seel in safety, but it was not the "trip of a lifetime." But the Park Service had little more than spectator status. [31]

The Memorandum of Agreement gave the Park Service greater influence over the activities of the guided tour operation. The cooperative nature of the agreement enabled the Park Service to extend a helping hand to the Austins. The Park Service "loaned" horses to assure higher quality animals for visitors, took reservations, and in general sought to improve the quality of service whenever possible. But much of the change was cosmetic in nature, and the improvement in the quality of the tours was minimal.

The new level of Park Service involvement was a mixed blessing. By taking reservations and supplying horses, the staff at the monument exerted at least a little influence over the operation. But conversely, because the Park Service took reservations, visitors assumed that the agency had control over the operation. Used to the high quality of visitor service, they often found the Keet Seel horse trip lacking. Many were angry about what they considered a lapse in responsibility by the Park Service.

Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, complaints about the horse operation increased. E. K. Austin was a "rough customer," unpopular with his neighbors, one who knew him recalled, and others remembered him in a similar fashion. One former employee called him the "bully of the canyon," another acquired the habit of calling him "Edd the Pirate," and recalled that he had to separate Austin and visitors on more than one occasion. One former superintendent recalled members of the Austin family getting into a fight with each other during a meeting with park rangers.

Visitors were often dissatisfied with their trip with the Austins. "Half starved" horses, poor service, sullen guides, and drunkenness headed the list of complaints. Many people came to the Park Service to express their dismay, in the hope that an agency that had built its reputation on service could act to stop what many regarded as a blemish on its record. The Park Service had a standard reply that frustrated both NPS people and visitors: because the Park Service did not control the Austins' land, it had little control over the horse operation. "Things here on the Navajo Reservation are not like other places," Jack Williams wrote in response to one complaint. "We are faced with jurisdictional and political problems that only the Navajo Tribal Council can alleviate." [32] Combined with the growing number of visitors who wished to go to Keet Seel, the Park Service recognized that it had a potentially major problem.

By the early 1970s, a consistent pattern was evident. The NPS had few options. Because Navajo National Monument was essentially an inholding on the Navajo reservation, the kind of control to which NPS officials were accustomed was elusive. Without any direct authority over private land and unable to reach one portion of the monument without the use of the Austin's land, the agency had to deal with a difficult situation. The best management alternative was to co-opt the Austins: show them the potential economic and cultural advantages of the Park Service approach to visitor service.

The cultural difference between the Austins and Park Service was vast. The Austins spoke only Navajo, and while some communication in English certainly occurred, for a topic as important as this, it was imperative to find someone who could communicate in the Navajo language. In April 1973, Clarence N. Gorman, then superintendent at Wupatki National Monument and later superintendent at Navajo National Monument, was called to Navajo to help bridge the gap. Chief Ranger Harold Timmons presented Gorman with a four-page list of topics he wanted covered with the Austins. Issues such as the treatment of visitors, courtesy, safety, promptness, and communications with Park Service were paramount. At a meeting, really a visitor service seminar conducted in the Navajo language, Gorman tried to convey techniques that would result in better service and fewer complaints. In the aftermath of Gorman's visit, conditions improved and the number of unhappy visitors declined. [33]

But a gulf remained. Navajo guides and Anglo visitors had different perceptions of the trip. Navajos saw themselves as guides rather than interpreters. They perceived their responsibility as limited to the safe delivery of visitors to the ruin and back. With a more instrumental than romantic approach to their animals, the guides often seemed uninterested and cruel in the eyes of their customers. A constant stream of complaints continued, reflecting a difference between expectation and actuality that characterized cross-cultural relations. The Park Service still had little ability to exercise substantive oversight. Ironically, for many visitors, riding horses with Indians on their trip to the ruins had significant cultural meaning. Despite any shortcomings, the Austins were part of the monument, their horse business an important component for visitors who sought a sense of being in the wild. [34]

The gift and craft shop authorized under the Memorandum of Agreement involved a different kind of relationship. Again the shop was independent of the park, although it was physically attached to the Visitor Center. The gift and craft shop was designed to expose visitors to Navajo crafts, increasing their visibility and showing Navajo craft work to the public. The Navajo Guild initially operated the shop, opening for business in April 1966 under its first manager, Ben Gilmore. When the travel season ended in October, the shop had grossed more than $13,000. Generally the shop was open for visitors, although closures usually happened on the weekends, when traffic was at a peak. The guild had a brief tenure at the monument. As a result of an administrative problem with the Tribal Council in Window Rock, the guild folded, and the shop became a private enterprise. Throughout the 1970s, Fannie Etcitty managed the shop, which by all accounts functioned well. In 1978, Superintendent Hastings complimented Etcitty on her operation, remarking that the "shop is always clean, your sales people do an excellent job, and the merchandise is of the best quality." Under Etcitty's management, the shop had become an asset for Navajos, park visitors, and the Park Service. It seemed a model of successful cooperation. [35]

A locally inspired powerplay forced a change in management. In 1980, Elsie Salt, a woman from the Shonto vicinity, acquired a lease from the Navajo Arts and Crafts Association to run the shop. Fannie Etcitty also had an agreement. Art White, by then general superintendent of the Navajo Lands Group, needed to know who was authorized to operate the store. On May 14, 1980, the Advisory Council of the Navajo Tribal Council granted Elsie Salt permission to run the store. She had been selected over Etcitty because she was from the Shonto area. Feeling wronged, Etcitty had to be threatened with eviction by the Tribal Council before she would leave her store. [36]

Under Salt, relations were sometimes strained between the park and the craft shop. NPS officials were less than impressed with her operation. One management team that reviewed the park regarded the entire craft shop operation as "highly unusual." Intermittent tension ensued, sometimes involving personality conflicts. [37]

More troublesome was a pattern of irresponsibility of which superintendents took notice. The store functioned on its own schedule, opening erratically and frequently closing after an hour or two. In 1988, Salt lacked a valid lease, the necessary insurance, and an adequate plan of operation to secure a permit from the Kayenta Regional Business Office for Accelerated Navajo Development. In the summer of 1988, the Tribal Council was not anxious to renew her lease. Salt was enrolled in the Kayenta Chapter, but technically the shop was in the domain of the Shonto Chapter. She needed approval of the Shonto Chapter to run the shop, but a number of its members wanted their chance at the operation. The Park Service also felt the need for greater control over the shop. Clarence Gorman believed that the circumstances were far too favorable toward Salt. "With Elsie having no lease, not paying rent, and operating out of a space in the Visitor Center," he told Regional Director John Cook on September 9, 1988, "I would say she has it made." [38]

While the Park Service sought to determine a strategy to resolve the problems with the gift shop, tragedy struck. In a one-car accident on May 31, 1990, Elsie Salt died. For the 1991 season, her sister, Sally Martinez was selected to manage the store. After renaming the shop "Ledge House Ruin Crafts," Martinez prepared to open for the 1991 season.

Like the horse trips, the gift shop had a cultural meaning that far exceeded the obvious. The direct interaction with Indians appealed to the traveling public in an overwhelming way. The gift shop allowed visitors to participate in the past in a way that purchasing books and other educational materials from the SPMA display in the visitor center did not.

The activities of the Austin family highlighted the differences between the two different kinds of economic relationships Navajos had with the park. The Austins had strictly economic motives, but nearly complete control over their interaction with the Park Service. Those who worked for the Park Service were mostly bound to its rules, regulations, and expectations. One group had greater autonomy; the other, greater security. Despite the potential for envy and conflict between the two groups, no evidence of rivalry appeared.

Relations with the pack trip operation and the gift shop revealed the give-and-take relationship between the park and the Navajo Nation following the Memorandum of Agreement. The agreement gave the Navajo a new hold on the park. The lease of the land through a semi-permanent interim agreement afforded Navajos a greater measure of control over their activities within the park than was previously available. What resulted was a series of compromises that eroded the measure of control that the Park Service previously enjoyed, but conversely was absolutely necessary to conduct the affairs of the monument. The greater the participation and sense of entitlement and belonging of the Navajo people, the harder it became to run Navajo National Monument like the rest of the system. The monument had always been unique, and the Memorandum of Agreement reinforced that perception. The agreement gave the Navajo certain rights and privileges that were not always within the bounds of ordinary NPS policy. The interdependence of the area further affirmed the need for a compromise-oriented agency posture.

By the mid-1980s, the pattern of attending to the needs of the area as well as of the park was firmly ingrained at Navajo National Monument. There were efforts by the Navajo to tie into the electricity and sewer systems of the monument. Because of the limited capacity of both, at the end of the 1980s such requests had not been filled. But the trend had been established, at least to a certain degree. The amenities and advantages of the park would be available to some of the Navajo some of the time.

The appointment of Clarence N. Gorman as superintendent in 1986 inaugurated a new era. A Navajo, Gorman once worked as a seasonal ranger at the monument. More than twenty years later, he returned as the head person at the park. Gorman's appointment reflected the importance of close relations with local people. Many of the Navajo employees felt a stronger feeling that they belonged after Gorman's appointment, knowing that they would return to work each day with other Navajos, speak the language, and experience a certain feeling of accomplishment. There was a stronger pride in working for the park for Navajos working for a Navajo superintendent. "It's good to see your own people working here," Delbert Smallcanyon said in the Navajo language. There was a measure of freedom that Navajos did not experience working for industries such as the railroad. [39]

To the people of the region, the presence of Navajo leadership also inferred a gradual transfer of the monument to the de facto custodianship of the Navajo people. In the fall of 1990, Gorman arranged for the return to the Barlow family of the very medicine bundle that had been the subject of controversy in the early 1970s. Even though the bundle--called a jish--had been purchased from the family, the Park Service did not request reimbursement. Another jish was given to Navajo Community College near Chinle for its "lending library" designed to help teach the practices of Navajo medicine men to new generations of the Dine. These gestures, of a piece with an emerging enlightenment in the scientific community regarding prehistoric and historic artifacts, typified the heightened level of concern for Navajo sensitivities.

Yet the growing presence of Navajo people did not indicate a dislike of previous Anglo superintendents. Most of the past Park Service officials were fondly remembered by many of the Navajo in the area. Art White particularly was revered by area people, as were others who sought to build a relationship with people in the region. Only one was mentioned in an unfavorable light, ironically by both Navajos and Anglos who worked for him. According to accounts, he had a textbook view of Indians and had difficulty adjusting to living among real ones. [40]

Gorman's appointment had symbolic overtones. It reflected two decades of growing empowerment of the Navajo and American Indians in general and the overwhelming desire of the Park Service and federal agencies to operate in a more inclusive fashion. A career Park Service professional who worked his way up the ladder, Gorman's position as the highest GS-rated official at the park spoke volumes about inclusiveness to the people of the region. Some of the sub-surface tension about NPS presence was mitigated by having a Navajo in a position of leadership.

Gorman's presence also widened the role of Navajos at the park. Because of its unique geographic position in relationship to the location of labor, the park could hire area Navajos without going through standard federal employment procedures. Support programs that included Navajos also grew, and Navajo history and culture played a growing role in the interpretation. Efforts to include high school students from the area in summer activities at the park followed. In the summer of 1988, five young Navajos from the Shonto Chapter worked at the monument.

The Navajo Nation also became increasingly aware of cultural resources in and around the reservation. This resulted in legislation designed to protect the interests of the Navajo people. One such law, the Navajo Nation Cultural Resources Protection Act, seemed inapplicable to NPS activities. The Park Service chose to respond to it on a case-by-case basis, preferring such a tactic to an open challenge. But passage of the act reflected the fundamental changes in Navajo-park relations that followed the Memorandum of Agreement in 1962. In 1909, the Navajo people had yet to adapt their leadership structure to the realities of outside encroachment on reservation life. The Navajos exerted little if any influence on the park or the Park Service. By 1988, with a governmental and legal structure in place and a clear sense of their identity and rights, the Navajo Nation was a force with which the Park Service had to contend. The Park Service moved carefully in Navajoland, not wishing to alter the pattern of good relations that had lasted more than three generations. [41]

But the Navajo Nation was powerless to slow the pace of change for many of the Navajo people. By the 1980s, Navajos on the western reservation were a people in transition. The roads that crossed this previously isolated area had brought the cultural impact of the modern world, and the traditional ways of living that had lasted in the remote parts of the reservation began to change. Younger people began to lose their ties to traditional culture, although not at the rate that occurred among more urbanized Navajos. Yet many of the younger people moved away in order to find work, settled in Flagstaff, Phoenix, Los Angeles, or some similar place, and began the transition to urban status. Even the most traditional people were involved in the modern economy. Hubert Laughter, who worked at the park, became a Navajo Tribal Police officer, served on the tribal council, was later drove heavy equipment for the Peabody Coal Company, and also a medicine man. A man packing squash and gourds to the Inscription House Trading Post that Bill Binnewies met in the early 1970s typified the duality. When not engaged in such subsistence economic activities, he was a technician for a guided missile system. Clearly this was a harbinger of a complicated future. [42]

These contradictions characterized the future predicament of the Navajo people. Caught with a foot in two distinctly different worlds, they will have to fight to retain cultural individuality. A recent trip to the Farmington Mall revealed scores of young Navajos in the classic garb of the generic teenager: unlaced tennis shoes with the tongues hanging out and heavy metal T-shirts of popular groups. The demands of the modern world have an overwhelming character. They hegemonize indiscriminately.

Ironically, when young urban Navajos seek to rediscover their own culture, places like Navajo National Monument have the potential to play an important role. As the monument fused more and more with its surroundings, it became a haven for Navajos who sought to remain Navajo but have many of the material advantages of the modern world. In the early 1990s, the character of the workforce of the monument was Navajo--very traditional Navajo. Even younger Navajo members were attuned to their unique and protected position as employees of the park. By providing the benefits of mainstream American life without many of its drawbacks, the monument insulated the people of the region from the worst effects of change. In addition, interpreting Navajo culture at the monument was on the upswing, and the growing number of Navajos in the work force at the monument assured greater future presence. The bits of Navajo culture preserved in places like Navajo National Monument can provide a visible guidepost for young Navajos as they seek to reattain what they earlier shunned for the perceived advantages of "civilization."

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

nava/adhi/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006