|

Navajo

A Place and Its People An Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER VII:

ARCHEOLOGY AT NAVAJO

Navajo National Monument was established as part of the push to preserve the remnants of the pre-Columbian past scattered across the western landscape. Reserved as a series of archeological sites rather than as a management entity, the monument was subjected to a range of influences from its inception. Archeologists of different backgrounds sought to excavate the region even before the monument was established. An awkward pattern of excavation and explanation of the prehistory of the Tsegi canyon area followed.

Archeologists who sought to learn the prehistoric story of the Kayenta Anasazi from the monument faced other problems. Navajo National Monument had been reserved to protect above ground ruins, not as a way to protect the remains of a culture group. The proclamation of the monument resulted from the fear that ruins would be damaged, not from any sense of the pieces of the past it held. As a result, the monument included episodes of the past, not a comprehensive picture, and archeologists and aficionados who sought to understand these ruins often had to rely on work done outside its boundaries. Synthesizing the information for the purposes of the monument was a difficult and complicated task.

The process of rediscovering the prehistory of the Tsegi Canyon vicinity also fell prey to jurisdictional issues. The boundaries of the monument limited the area in which archeologists had influence. Excavation proceeded in an erratic fashion, shaped as much by the availability of locales as by the objectives of scientists and institutions. As was typical of the experience of the agency in this area, the Park Service found itself powerless. The agency had influence over only a small part of the region and control of even less. Unable to regulate archeological efforts, the Park Service concentrated on preserving the ruins of the monument.

The study of prehistory was in its infancy at the turn of the twentieth century. Following 1840, archeology moved toward becoming a respectable field of study in the U.S. Prior to the middle of the nineteenth century, the field had been largely speculative. In the subsequent decades, proto-archeologists developed a descriptive style, designed to taxonomize the sites they found before them. As they began to be exposed to the ruins of the Southwest after 1880, this descriptive approach seemed sufficient. With so many places to inventory and catalog, most archeologists were content to record what they saw. [1]

Yet there was an intellectual dimension to the archeological profession at the turn of the century. In the late 1870s, Lewis Henry Morgan, regarded as the father of American anthropology, posited a series of stages of cultural evolution. Neo-Darwinian and ethnocentric in their hierarchical nature, Morgan's theories were as applicable to prehistory as to existing tribes. Among the many Morgan influenced was Adolph F. A. Bandelier, the scion of a Swiss-American banking family from Illinois. Bandelier became obsessed by southwestern history and prehistory, walking the region to historic and prehistoric villages and publishing major works. While the majority of Bandelier's work was taxonomic in character, it helped fill many intellectual gaps and spurred others to investigate further. [2]

An institutional base for the study of the prehistoric and historic past also emerged after 1875. Archeology in the U.S. prior to that time had focused on Europe and the Middle East, with much of its effort expended on religious themes. But the opening of the West extended new opportunities to the coming generation of scholars, and they developed an infrastructure to support their efforts. Journals such as the American Antiquarian, founded in 1878, and American Anthropologist, which commenced publication a decade later, played important roles, as did the Anthropology section of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the Archaeological Institute of America, and other similar organizations. [3]

Perhaps the most important element in the emergence of an institutional base was the support of the federal government. This resulted from the surveys of the American West that begin with Lewis and Clark in 1804, continued intermittently until a spate of military surveys in the 1840s and 1850s, and grew in size and scope following the Civil War. John Wesley Powell, one of the leading explorers of the post-Civil War era, played an instrumental role in the founding of the Bureau of Ethnology, a branch of the Smithsonian Institution, in 1879. With the charismatic Powell as its head, the bureau explored the prehistory and history of the West in an effort to use the past to justify the direction in which American society had traveled. In this view, anthropology and archeology were supposed to carry redemption to what had become an industrial and callow society. [4]

Standing between institutionally based science and its objectives were amateurs with an interest in the remains of prehistory. The best known of these was Richard Wetherill, the rancher from Mancos, Colorado, who knew the Southwest like the back of his hand. Wetherill dug where he pleased, for no law restricted his behavior. Besides the Keet Seel ruin, Wetherill was the first Anglo to excavate the Mesa Verde area, Pueblo Bonito in Chaco Canyon, Grand Gulch, Utah, and a host of other southwestern sites. [5]

Linking together a number of the currents in American society at the beginning of the twentieth century, institutional scientists vilified Wetherill. A growing self-consciousness pervaded American society as the nation began to recognize its inherent limitations. The idea of scarcity, never before a feature of the New World psyche, came to the fore as Americans realized that their continent was finite. A backlash against European culture also erupted as Americans tried to convince themselves that the natural grandeur of the continent equaled European cultural history. Wetherill seemed a threat in both areas; his first "client" was Gustav Nordenskiold, a Swedish baron's son who made a vast collection in the ruins of Mesa Verde and took it home with him. This led jingoistic scientists to revile Wetherill for expropriating American prehistory for European benefit. As Wetherill explored various sites and made collections of pots and artifacts, he transferred part of the past from public to private hands. In an era that slowly came to recognize scarcity as a reality, his behavior bordered on heresy. [6]

But Wetherill himself was heir to a long tradition in the history of archeology. He was the talented amateur, like Heinrich Schliemann and a host of other eighteenth- and nineteenth-century archeologists. Wetherill made numerous discoveries, at least one of which, his recognition of pre-pueblo phases of southwestern life called Basketmaker culture, revolutionized archeological thinking. Wetherill's real crime was that he remained an unaffiliated individual in an era of growing emphasis on credentials and institutional affiliation. [7]

His work differed little from that of most of the archeological profession at the turn of the century. Archeological research meant making collections of prehistoric artifacts. Museums and other similar institutions competed for control of the field as they sought to acquire prehistoric relics. Some institutions developed close relationships with people on the fringes of the profession. The close ties between Richard Wetherill, a number of private sponsors, and the American Museum of Natural History in New York typified the nature of such contact. The thin line between pot-hunting and recognizable science was easily erased.

The chaos this situation engendered led to legislative and practical responses. Beginning in 1900, a number of bills designed to protect prehistory from unsanctioned excavation were proposed. After six years, the movement to preserve prehistory reached its zenith in 1906, when "An Act for the Preservation of American Antiquities," more commonly known as the Antiquities Act, and a bill to establish Mesa Verde National Park became law. The Antiquities Act allowed the president to reserve historic, prehistoric, or natural areas from the public domain as national monuments. Finally, the rudiments of a system to protect prehistoric resources was in place. [8]

But the results of nearly three decades of a general lack of protection had been disastrous. From the Rio Grande Valley to southern Arizona, ruins had been pillaged wholesale. In search of artifacts, professional and amateur collectors had overturned walls, ripped through ruins, and dug nearly every easily accessible prehistoric locale. Collectors and souvenir-hunters alike gorged themselves on whatever they could find. The archeological community watched in horror.

The western portion of the Navajo reservation was exempt from much of this activity. Few Anglos ventured into the heart of Navajo country before the turn of the century, and those who did often found themselves unwelcome. Occasional clashes between Navajos and intruders in their land occurred well into the 1910s. The gradual settlement process that followed the course of the river basins and railroads of the region was largely absent on the reservation. Richard Wetherill was an exception. Besides his forays to Keet Seel in 1894-95 and 1897, he visited a number of other ruins in the area.

When John Wetherill moved his trading post from Oljato to Kayenta in the fall of 1909, the ruins of the western reservation and Tsegi Canyon in particular came within the reach of the archeological community. Yet the opening of this area occurred in the aftermath of the passage of the Antiquities Act, allowing an increasingly interested federal government a greater measure of control over the disposition of these ruins than any prior group. As a result of Richard Wetherill's excavation at Chaco Canyon, Congress developed laws to protect ruins. As William B. Douglass battled to stop the Cummings expedition in 1909, a system that could protect ruins, albeit in a rudimentary fashion, was in place.

This defined the history of excavation of the ruins of Navajo National Monument. After Richard Wetherill's preliminary efforts at Keet Seel, every major excavation that occurred at the ruins had been authorized by someone in the federal government. In 1909, Hewett and Cummings requested and received permits, and Fewkes was a representative of the Smithsonian Institution. The result was a more orderly process than occurred nearly everywhere else in the Southwest. While federally authorized excavators could be careless and haphazard, they were part of an official system that required some measure of accountability.

But the ruins in the Tsegi were reserved because they were seemingly untrammeled visible evidence of prehistory, not because they represented a comprehensive prehistoric community or time period. They were episodes, not a chronological sequence, limiting their importance as individual subjects of study. Nor were they reserved to provide a comprehensive picture of the past of the region. Understanding the prehistory of the monument meant studying the entire Colorado Plateau.

The initial generation of archeologists were not well equipped to unravel the mysteries of the past. They brought the assumptions and techniques of their era to a world that functioned by a different set of rules in both past and present. Influenced strongly by Morgan and other late nineteenth-century thinkers, they saw through an ethnocentric prism that limited their ability to understand the methods and motives of prehistoric people. Most had little academic training in their chosen field, but acquired their knowledge while doing fieldwork. Nor were the techniques of their time particularly sophisticated. Faced with thousands of ruins, this initial generation acted as had Bandelier more than three decades before. They described what they saw, drew maps of ruins and rooms, and provided essential basic information. But few did more than take field notes, and little of such work was published in a timely fashion for the use of other scholars. Field techniques and procedures were not yet standardized. A largely incomplete set of data resulted. While many excavations occurred on the Colorado plateau, little consensus about the patterns of prehistoric life followed.

The condition of surface ruins after an excavation was incidental to the progress of archeology in this era. More concerned with the artifacts they found and their broad generalizations about the prehistoric past, most of the first generation of archeologists used ruins for their own purposes. Like the pot-hunters they feared, they too tore through ruins, digging hastily and capriciously. There was little thought or care to the long-term survival of the ruins they excavated.

During the initial era of inquiry, which lasted well into the 1930s, archeologists explored northeastern Arizona. They mapped some of the ruins in the region, performing preliminary excavations and beginning the long and complex process of assembling data. As occurred elsewhere in the world, the initial generation to explore the region faced the problems of being first. Limited by the techniques of their time, little funding, lack of prior knowledge and context in which to locate their discoveries, and their cultural outlook, many found little information but used it to speculate wildly and generalize broadly. [9]

By the end of the 1910s, a new style of archeological practice was coming to the fore. Initiated by Nels V. Nelson and Alfred V. Kidder, archeologists began to adapt the stratigraphic techniques of nineteenth-century archeologist Max Uhle to the American Southwest. At Galisteo, Nelson began the process; Kidder's recognition of changes in architecture, ceramics, and skeletal attributes at Pecos led to the first major chronological sequences of pueblo prehistory. Archeology was moving past description as an end at precisely the moment that the monument and its environment was first subjected to rigorous excavation.

The Colorado Plateau became a center for early excavation efforts in the years following 1909. John Wetherill served as a guide for a multitude of explorers in the region. Between 1914 and 1927, Kayenta became the center of a frequently explored area. The Peabody Museum's Northeastern Arizona Expedition became the dominant group as it sponsored study of the many facets of the region and established a pattern that would become ingrained in southwestern archeology. The broad-based focus inspired more widespread expeditions headed by Kidder, Samuel J. Guernsey, and Noel Morss that examined numerous locations in the area, including the west side of Monument Valley, sections of the Chinle Wash, and Tsegi drainage system. [10]

According to later archeologists, Kidder and Guernsey's work initiated serious modern archeology in the region. Sponsored by the Peabody Museum, the 1914 and 1915 expeditions they headed were the first to report on the findings in a systematic and timely fashion. Kidder and Guernsey's work demonstrated stratigraphic and material culture differences between "basket-maker" and cliff houses materials, and allowed them to postulate the existence of a phase of culture located chronologically between the two. [11]

|

| Food or corn grinding place in Betatakin Ruins. Photo by Luke E. Smith, 1921. |

With a chronology posited, Kidder and Guernsey explored further. If the different temporal phases existed, archeologists thought they could describe and detail the differences. The Peabody Museum backed expeditions in 1916 and 1917, out of which came Guernsey and Kidder's Basket Maker Caves of Northeastern Arizona, published in 1921. In the 1990s, this work remained a major reference on Basketmaker II material culture. Further work between 1920 and 1923 added architectural detail and broadened the quantity of artifacts that substantiated the new generalizations. [12]

During the 1920s, a range of institutions and individuals sent expeditions to northeastern Arizona. Many archeologists learned their trade in the area, and a kind of mini-boom in interest resulted. But only a few of the expeditions pursued the advancement of knowledge. Many others sought to make collections for museum cases or personal edification. Charles L. Bernheimer sponsored an expedition nearly every year in the 1920s, as did the Public Museum of the City of Milwaukee. These collecting forays did little to advance the state of knowledge about prehistory in the region. Other work resulted in advancement of the chronological sequences that Kidder and Guernsey pioneered. Harold S. Gladwin, Arthur Woodward and Irwin Hayden, and Monroe Amsden conducted excavations that yielded much new contextual information that helped unravel the story of Navajo National Monument.

A major advancement in the ability to discern prehistoric information occurred in this era, shaking up the present and laying a basis for the future. Astronomer Arthur E. Douglas of the University of Arizona had long studied southwestern tree-ring growth to aid his sun spot research. By the late 1920s, he had surveyed both living trees and prehistoric timbers preserved in ruins. In 1929, he had two long chronological sequences, one dating from the twentieth century back into the late prehistoric period, about 1,300 C.E., the other a floating chronology not linked in time to the first. That summer, Emil W. Haury, a young archeologist, discovered a piece of charred wood that established the basis for a link between the two timelines. In one brief moment, chronological dating of prehistoric sites became empirical. This set the stage for a major revolution in the way archeologists perceived the past as well as in their ability to base chronology on much more than educated speculation. [13]

|

| Betatakin Ruins (hillside house), near Kayenta, Arizona, May 1921. Photo by Luke E. Smith. |

Dendrochronology, the science of tree-ring dating, and stratigraphic cultural sequencing laid the basis for a revolution in the way in which archeologists collected and understood information about the past. A new era in the archeology of the region followed, characterized by greater systematization and classification, and more emphasis on the construction of prehistoric chronologies and regional culture history. [14] Unfortunately, the collapse of the financial markets in 1929 limited the ability of many potential patrons to support an expedition. Despite new knowledge and methods, archeologists had to wait to apply them.

The Rainbow Bridge-Monument Valley survey, a traveling expedition that spent every summer from 1933 to 1938 in northeastern Arizona and southeastern Utah, provided the mechanism that became the next attempt at comprehensive study of the region. Conceived and headed by Ansel F. Hall of the Park Service and shaped by his interests, the expedition made field collections, selective archeological studies and excavations, and mapped the physiographic and geologic features of the area. An array of scientists from different fields participated, including archeologists, paleontologists, biologists, and geologists. They excavated in an immense area that stretched from Marsh Pass well across the Utah border on the Rainbow Plateau.

The Rainbow Bridge-Monument Valley expeditions added to the large stores of data collected in the vicinity of the monument. Field parties combed the region, surveying and excavating in a number of places. As many as seventy people participated from base camps located first in Kayenta and later in Marsh Pass. Lyndon Hargrave of the Museum of Northern Arizona supervised archeological work the first two years, and was succeeded by Charles D. Winning of New York University. Working at a range of sites, participants in the expedition uncovered much information that helped explain the story of the Kayenta Anasazi. These efforts paved the way for the first systematic inventory of archeological resources in the Tsegi Canyon system.

The discoveries of the Rainbow Bridge-Monument Valley expeditions also helped add to the advance of archeological knowledge in the region. With the methods to date and order the prehistoric past, archeologists could use data to systematically categorize the past. Accurate chronological sequencing was developed, and the addition of information from the surveys gave a broad-based picture of the level of technology, the nature of trade, and many other aspects of prehistoric life.

|

| Betatakin Ruins, May 1921. Photo by Luke E. Smith. |

For Navajo National Monument, these efforts initiated new approaches to the story of the park. The monument benefited both from the attention focused on southwestern archeology as well as the new information that helped explain the past. A systematic approach offered much to the Park Service and the Southwestern National Monuments Group as Frank Pinkley sought to interpret prehistory for the public.

Archeological work in Navajo National Monument predated the beginning of a systematic approach to archeology. It preceded the founding of the monument by more than a decade, reflecting the earliest trends in the history of southwestern archeology. In January 1895, Richard Wetherill, Alfred Wetherill, and Charlie Mason found Keet Seel. They began to explore the area, inspecting the trash midden, making an extensive collection of pottery, and describing the ruin. Wetherill counted 115 rooms on his first trip, informing his partners--the Hyde brothers--that Keet Seel was "the best place to get a collection I ever saw." [15]

That sentiment spurred Wetherill's return in 1897, when he again excavated in the ruin, this time to quench his sponsor Teddy Whitmore's desire for a collection. On this trip, Wetherill diagramed the floor plan of Keet Seel and measured its dimensions. The party also dug in numerous places in the ruin in search of artifacts. [16]

Wetherill's sentiments typified the character of excavation in his era. Late in the 1890s, the uproar concerning his activities remained muted. Federal officials had yet to take umbrage at his actions. Wetherill was merely a well-positioned competitor in the hunt for artifacts that dominated the horizons of the archeological community. He and his party collected artifacts and did some preliminary excavation. Wetherill himself made field notes of the activities.

In the decade that ensued, the climate in the archeological profession changed. Wetherill was labeled a pot-hunter by federal officials and academic and government scientists alike, and the GLO made serious if sometimes misguided efforts to protect important ruins. A permit system was established, although its creator, Edgar L. Hewett, used it as a license to hoard a large piece of archeological turf for himself and his friends. But by 1909, when William B. Douglass recommended the establishment of Navajo National Monument, a different set of assumptions governed both his efforts and those of other federal officials.

The attempts to use federal power to halt the previously authorized excavation of Byron L. Cummings in the summer of 1909 reflected the changes. Cummings fit the profile of the first generation of American archeologists. Self-trained in archeology but possessing other academic credentials, Cummings found his position at the University of Utah to be an opportunity to be part of the growth of an exciting new field. Protected by Hewett's permit, he seemingly had every right to excavate in Tsegi Canyon in 1909. But much of the power of the Smithsonian Institution, the General Land Office, and the Department of the Interior joined to prevent his actions. [17]

Yet Cummings managed to excavate within the monument not only in 1909, but, with an important two-year exception, in nearly every year that followed through 1930. Most of his field work had the emphasis on collections typical of the era. Any publications that resulted were descriptive in character. Cummings and his party set up camp at Keet Seel in the summer of 1909, working there until July. A trip to Nitsin Canyon made them the first official party of Anglo-Americans to see Inscription House. On their return, they were directed to Betatakin, which they investigated for the better part of an hour before Cummings headed off in search of his real objective that summer: the location of Rainbow Bridge. As a result, most of their activities that first summer were preparatory in nature, reconnaissances designed to prepare for future work. [18]

There was also a cavalier dimension to such work, particularly in the eyes of federally affiliated scientists and bureaucrats. With his overriding interest in Rainbow Bridge, Cummings seemed to fashion himself as much an explorer as an archeologist. To those who questioned the integrity of western academics, he seemed the epitome of a man in search of the limelight. Perennially in search of a new discovery, Cummings appeared to lack the ability to see a project through to fruition.

With this feeling foremost in their thinking, Frederick Webb Hodge of the Bureau of American Ethnology and Charles D. Walcott of the Smithsonian Institution sent J. Walter Fewkes to Navajo National Monument to make a preliminary, if permanent, assessment of the attributes of its ruins. The monument had yet to be reduced to its final size and did not then include Inscription House. As a result, the Fewkes party visited Betatakin, Keet Seel, and a number of smaller ruins within the general area. At each site, Fewkes compiled intricate descriptions of archeological and architectural features, creating the kind of record of which a society that sought to document its past could be proud. [19]

There were differences in character between Fewkes' two trips and the summers that Cummings spent in the region. Fewkes represented the federal government and was not bound by the demands upon either academics or museums. Fewkes and the Bureau of American Ethnology regarded the monument as the property of the public. Documentation rather than excavation appeared to be their objective. Cummings used the ruins in a time-honored archeological fashion. He brought students with him to train, including Neil Judd and more than two decades later, the distinguished Americanist Gordon R. Willey; made collections; and generally behaved in what federal officials regarded as a proprietary manner. A contest between generations of the archeological profession was underway.

Changing realities in the region did not deter Cummings. He returned to dig Betatakin even as Fewkes approached. But the results of the excavation provided ammunition to those who sought to restrict access to the ruins. Forced to leave in haste by approaching bad weather, the Cummings party left a number of artifacts hidden in the ruin. They were never again seen.

Cummings' foray in the fall of 1909 was his last in the area until Fewkes departed. Only in 1912, after Fewkes was gone, did Cummings return to Betatakin. He continued his practice of taking students with his parties as trainees in the summers, excavating Inscription House in the summer of 1914. But after the Fewkes survey, Cummings became less important as the objectives of government-sanctioned science took hold.

Almost a decade after the creation of the monument, Congress finally invested in the upkeep of its national monument. An appropriation in 1916 allocated $3,000 for the preservation and repair of the ruins in the monument. The Smithsonian Institution was designated to administer the funds. Cummings' student and nephew Neil Judd had gone to work for the National Museum, a branch of the Smithsonian, in 1911. He served as an excellent compromise candidate to lead the party. Cummings himself wanted the opportunity and pressed for it through his congressmen and senators. BAE and the Smithsonian wanted someone over whom they held sway. Judd was acceptable to Cummings as well. In March 1917, Judd was named head of the field party and he headed West. [20]

On his arrival he realized the scope of the problems at the monument and made an important decision. With only a small appropriation, he could not do everything and chose to confine his efforts to Betatakin. One objective was to protect the ruins that had been previously excavated; Judd and his crew repaired Betatakin, reconstructing walls with mortar he replicated from prehistoric mortar that outlasted the sandstone building blocks of the Anasazi. Another was to collect artifacts and inventory architectural details, such as the lateral depressions "pecked with stone hammers" that allowed the Anasazi to have a seating on which to build their walls. [21]

The appropriation for repair was a figurative drop in the bucket. Each of the ruins had problems that required attention, but the money and workpower were not sufficient to solve them all. Nor did Judd have much time. His party arrived at Betatakin at the end of March and the federal budget expired at the end of June. The U.S. entered the First World War a few days after Judd's arrival, assuring that any money left at the end of the year would have to be returned to the federal treasury. The project progressed in a hurry, accomplishing what it could in the hope that more money would be forthcoming. [22]

But the establishment of the National Park Service created an entity responsible for Navajo National Monument, and no further direct funding for the monument followed. At its inception, the Park Service had few resources and many responsibilities. It was involved in a struggle for survival as a federal agency. A hiatus in government-sponsored science that lasted for more than a decade followed. During this era, the agency focused on the parks and monuments that could be used to develop a national constituency. With few resources and a vast and growing domain, the agency could not support efforts at every park area. What work was done was performed by museums during the 1920s. Only during the New Deal did federal efforts again extend to peripheries like Navajo National Monument. [23]

Museum-sponsored science dominated the 1920s. Under the aegis of the Peabody Museum's Northeastern Arizona Expedition, Alfred V. Kidder headed a field party that excavated Keet Seel and Turkey Cave in 1923. Other major archeologists also worked with the expedition. Among them was Harold S. Gladwin, who excavated Turkey Cave in 1929. A broader picture of the prehistory of the region based on efforts to develop a chronological sequence began to emerge from their efforts. But while these efforts added much to the knowledge of prehistory, they did little to preserve the ruins of the monument. [24]

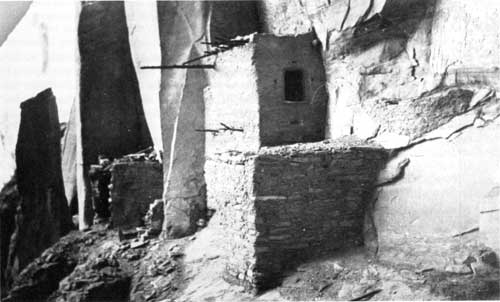

|

| Keet Seel in 1914, after Richard Wetherill's visits, but before stabilization work had been performed. |

By the 1930s, the Park Service had a different set of objectives for archeological work. During the 1920s, visitors had started to come to the southwestern monuments in growing numbers. Many of the ruins were fragile, excavated poorly or arbitrarily before the Park Service had been created. Facing a seemingly never-ending parade of visitors meant damage to unprotected sites. From the point of view of the Park Service, stabilization became far more important than excavation and collecting.

This duality of purpose came to characterize archeology at Navajo National Monument. The monument held an important piece of the prehistoric past, and archeologists sought to explore it. Concerned with its mission of preservation and visitor service, the Park Service focused on stabilization work, often in debris left by prior archeologists. With a variety of uses and constituencies, the monument ruins required different kinds of management.

But again the shortage of resources did not help the monument. During the 1920s, Frank Pinkley received little funding to support the more than 250,000 visitors that explored his sixteen monuments. Stabilization was a haphazard process, usually done by the monument custodian and Pinkley himself, and confined to the most traveled monuments. With less than 500 visitors per year throughout the 1920s, Navajo National Monument rarely qualified. [25]

The New Deal increased the opportunities for remote monuments like Navajo. Through the Emergency Conservation Work program, funding for labor became easy to identify. Although it never received a camp or side-camp of its own, Navajo did benefit from the vast array of resources at the disposal of the Park Service.

|

| CWA workers helped to stabilize Keet Seel in the 1930s. |

During the 1930s, two of the three major ruins in the monument received attention from the NPS. Judd's stabilization work at Betatakin in 1917 had held up well. In the early 1930s, there seemed no need for additional work. Keet Seel faced greater threats. Little work had been done in the ruin since the era of Wetherill and Cummings, and it was in need of stabilization. For this purpose, the Museum of Northern Arizona sponsored a project funded through the Civil Works Administration. Archeologist Irwin Hayden took charge of the project, which worked at Keet Seel and Turkey Cave in 1933 and 1934. [26]

Hayden's CWA project performed work similar in character to Judd's project in 1917. At Keet Seel, Hayden's crew cleared unexamined areas, removed the dirt from backfilled ruins, recorded architectural details, and rebuilt collapsed walls. Hayden also re-excavated and stabilized two kivas in Turkey Cave, according to John Wetherill, finding much that Kidder had overlooked in 1923. The work was done well, earning Keet Seel the reputation as one of the best-preserved ruins in the Southwest. [27]

Keet Seel also yielded some interesting discoveries. Early in 1934, Irwin Hayden and Milton Wetherill uncovered the skeleton of a child in a trash midden at Keet Seel. With the skeleton were two pieces of Pueblo II type pottery, far older than the ruin itself. Other finds followed, including what appeared to be the skeleton of a parrot. Such unexpected results showed that the "down-and-dirty" emphasis of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century archeologists on collecting left many hidden treasures. [28]

In 1939, Inscription House received attention from the Park Service for the first time. Charlie Steen, a veteran archeologist and Park Service man, headed the project. Steen's objectives were similar to those of Judd at Betatakin and Hayden at Keet Seel. Steen was more concerned with architectural documentation than reconstruction. He recorded room configurations, structural features, and construction characteristics, and took numerous photographs. Most of the rooms were not disturbed. Some mortar was patched, some bricks replaced, and a roof was repaired. [29]

The efforts of the 1930s reiterated the difference between the approach of the Park Service and previous excavators. NPS efforts were directed at restoration, stabilization, and preserving ruins rather than at making collections. Turkey Cave, with little value as visitor attraction, was a prime interest of archeologists. Keet Seel, Betatakin, and Inscription House, the large and visible surface pueblo remains, were the primary focus of government and NPS efforts.

While Park Service efforts were directed at making the ruins usable for the growing number of visitors, the Rainbow Bridge-Monument Valley expeditions sought to add to the base of knowledge. Among the places the survey worked was Navajo National Monument. [30] For the Park Service, this had many advantages. The agency could acquire additional information from the work of these archeologists, while focusing on its imperative: the protection and preservation of the ruins of the monument.

But the work of the Rainbow Bridge-Monument Valley Expedition created a controversy at Navajo National Monument. In the late 1920s, A. E. Douglass, the founder of dendrochronology, had taken core samples from the timber at Keet Seel, carefully plugging his holes. Neil Judd also took core samples, leaving the holes unplugged. But according to Irwin Hayden, in 1934, Lyndon Hargrave of the Rainbow Bridge-Monument Valley expedition and his party engaged in a "sort of sophomoric sawing spree," cutting the ends off of many of the timbers at Keet Seel.

A fracas ensued that disrupted the CWA stabilization program at the monument. Enraged, Hayden quit the project, walking the twenty-five miles to Kayenta. Julian Hayden replaced his father. But Irwin Hayden was not through. He took Hargrave to task with Harold Colton, director of the Museum of Northern Arizona, and Frank Pinkley, ever protective of the archeological resources of his domain, took Hayden's side. Colton sided with Hargrave. He and Pinkley exchanged heated arguments on the topic. Dendrochronology was a new science, and A. E. Douglass best understood it. Standards for use of the technique had not yet been developed. Until archeologists got together to work out the details, there was little chance of resolution. [31]

Repercussions continued. Jesse Nusbaum, by then director of the Laboratory of Anthropology in Santa Fe and former superintendent of Mesa Verde National Park, was distraught, as was Frank A. Kittredge, the chief engineer of the Park Service. "So many of the ancient logs had been sawed in two that it was most depressing," he conveyed to Arno B. Cammerer, director of the Park Service. Despite the advances in knowledge that stemmed from the work of archeologists, NPS goals of preservation and the objectives of the archeological community were not compatible. [32]

The end of the New Deal and the beginning of World War II halted most archeological work at the monument and in the vicinity. Federal funding for archeology dried up, and gasoline and rubber rationing curtailed opportunities for survey work. Park Service headquarters was moved to Chicago to make room for war-related agencies in Washington, D. C., and most park projects were postponed. The problems of Navajo National Monument did not merit a look during the war.

During the 1950s, scientific institutions re-entered the region. The Smithsonian Institution sponsored the Pueblo Ecology Study, while the Glen Canyon Project surveyed archeological resources in the vicinity of the Glen Canyon Dam. Preserved and protected, Navajo National Monument received some attention from these projects. The Glen Canyon project in particular had implications for the monument, investigating sites near its boundaries and with ramifications for its story.

Concomitant effort within the Park Service followed as the agency faced a dramatic increase in park visitation throughout the Southwest. The Southwestern National Monuments Ruins Stabilization program was established to assess maintenance needs of prehistoric and historic areas. As part of this program, Gordon R. Vivian examined Betatakin, Keet Seel, and Inscription House. While lack of protection loomed as an issue, he found the three ruins in good condition. His recommendations for future work led to Roland Richert's stabilization efforts at the monument in 1958. Richert's plan went beyond Vivian's recommendations, becoming a program for comprehensive stabilization and assessment. The result was a more thorough understanding of stabilization needs, a safer environment for visitors, and with the advent of Portland cement as a mortar for reconstruction, a presumed solution for the structural problems of stabilization. [32]

But the new material later caused many woes. Portland cement was harder and more durable than the material that it was supposed to preserve. It did not contract as it froze and thawed. Softer materials that the cement embraced--sandstone, limestone, and adobe--could not expand and contract with temperature fluctuation. As a result, the softer materials that Portland cement was supposed to preserve cracked and crumbled under the stress. Portland cement became the bane of stabilization. [33]

The stabilization work performed by Richert and his crew in 1958 was a watershed. At Betatakin, no stabilization had occurred since 1917; at Keet Seel, the ill-fated Hayden CWA project in 1933-34 had been the most recent effort, while at Inscription House, the stabilization was the first activity since Charlie Steen's work in 1939. Richert detailed the stabilization work, providing a comprehensive record of activities in all three ruins. At Keet Seel, forty-four rooms were stabilized. Wall foundations were shored up, roofs were patched and repaired, and stones were reset and jacal walls replastered. Even with the new Portland cement mortars available, Richert and his crew used a natural mud mortar. At Betatakin, the work was minor but widespread, occurring in twenty-five rooms. At Inscription House, another twenty rooms were repaired. [34]

This effort, major in comparison to previous endeavors, foreshadowed changes in the immediate future of the monument. MISSION 66 made the Park Service affluent. Throughout the park system, much long-needed work finally occurred. At Navajo, the encroaching pavement meant a greater need for constant maintenance of ruins in the monument. Visitation levels had begun to climb, and the plans for a visitor center and a paved approach road meant that the number would increase exponentially.

The archeological discipline had entered a new phase as well. In response to the rapid infrastructural and industrial development sweeping the Southwest after World War II, archeologists had begun to conceive of saving some information from ruins in the path of progress. Destruction could not always be prevented, but archeologists could perform surveys and excavations before the bulldozers arrived, collecting artifacts and making records for the future. Labeled salvage archeology, this proactive response came to dominate the field. [35]

Because of the authorization of the Glen Canyon Dam by the Colorado River Storage Project, much of the salvage archeology work focused on the area near Navajo National Monument. Work both in the area to be flooded and in the surrounding highlands added measurably to the base of knowledge for the monument. It also influenced the approach of the Park Service to the ruins of the monument. [36]

In the 1960s, NPS sponsored similar archeological studies within the monument boundaries. The new work ended a thirty-year hiatus in excavation within the boundaries of the monument. The prospect of greatly increased visitation made this work necessary, as the NPS geared up to fulfill its dual mission. The construction of the Kayenta-Tuba City highway, the approach road to the monument, and later the new road through Marsh Pass signaled the end of an era of isolation. No longer would remote character be a guarantee of protection. Nor would above-ground structures be immune to depredation. Greater preservation efforts were necessary as was more comprehensive research to support interpretation.

Two distinct kinds of work were performed at Navajo. Examinations to address concern for the resource comprised one category of work. In the 1960s, the monument embarked on a program of stabilization for the smaller ruins within the monument. Examples of these include the stabilization efforts of Charles B. Voll and an eight-man Navajo crew at Betatakin and Kiva Cave in 1964, test excavations of David Breternitz at Turkey Cave, those of Keith Anderson at Betatakin and Keet Seel, and the salvage operations of George J. Gumerman and Albert Ward of the Museum of Northern Arizona at Inscription House. Three others moved toward an understanding of the archeology of the monument: Jeffrey S. Dean's chronological analysis of Tsegi Phase sites, Polly Schaafsma's survey of rock art, and Keith Anderson's examination of Tsegi Phase technology, which became his doctoral dissertation. These efforts led to better understanding of Anasazi life in the ruins that composed the monument. The two different directions of archeology at Navajo National Monument had been fused.

Dean's work had particular importance for the archeology of the monument. During the early 1960s, he conducted his research at Navajo under the auspices of the Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research at the University of Arizona. The Park Service funded his research, as did the Arizona State Museum, and the work resulted in "Chronological Analysis of Tsegi Phase Sites in Northeastern Arizona." This effort, published in 1969 as a revision of Dean's doctoral dissertation, revised the chronology for occupation of the archeological sites within the monument. [37]

In his highly acclaimed study, Dean asserted that the Tsegi Phase Kayenta people did not move into the area in a comprehensive manner until about 1250 A.D., almost fifty years later than prior estimates. They found timber and other resources, and proceeded to make use of them, leading to a process of deforestation as trees were cut for construction. Dean discerned that the people who came to the Tsegi drainage had come from the Klethla Valley, Laguna Creek Valley, and Monument Valley areas, which had been nearly abandoned by 1250 A.D. The major factor that compelled their arrival was also what hastened their departure. Arroyo cutting as a result of their land practices made them search out Tsegi Canyon; the condition followed them, again forcing them to the south less than one hundred years later. [38]

More than twenty years after his research, Dean suggested a compelling reason for the construction of pueblos like Keet Seel and Betatakin under the ledges of caves. His own experience living in a pueblo convinced him that the primary reason was to limit the need for maintenance. Exposed, a pueblo required constant work. Wind, rain, and other elements made upkeep a struggle. The great ledges under which so many ruins were located protected them from much of the impact of weather, creating surplus time to devote to the necessities and amenities of prehistoric life. [39]

One of the most significant results of the explosion of archeological work that began at Navajo in the 1960s was a revision of the presumed age of the date on the wall at Inscription House. After extensive study, Albert E. Ward concluded that the year incised in the wall was more likely 1861 than 1661. He believed that members of a party of Mormons, who came to retrieve the body of a friend who had been killed by Navajos the previous year, carved the date. This reevaluation indicated that some changes in the historic chronology of the monument and possibly in the name of Inscription House site were appropriate. [40]

The Dean, Anderson, and Schaafsma studies laid the groundwork for the direction of archeological work at the monument. Stabilization and restoration remained critical features of NPS work at the monument, but broader knowledge was required to develop a more complete understanding of life at the monument.

During the 1960s, archeologists benefited from strong leadership at Navajo National Monument. Superintendent Art White and his successor Jack Williams were interested in the work of the archeologists and made sure that they received ample opportunity to do their research. "When I was in the archeology department, I did ranger work," White later remarked of his career as a park archeologist, "I didn't do any archeological work." He assigned ranger work to rangers, and let Keith Anderson function as an archeologist. Others on the staff sometimes resented this distribution of responsibility, but White deemed it necessary. [41] This luxury of workpower was a function of the affluence of the era, the unprecedented availability of resources that resulted from the MISSION 66 program. The increase in visitation compelled better research, protection, and interpretation. Superintendents who understood the need for new and different research helped lay the basis for the boom in archeology in the 1960s. Fortunately it occurred during MISSION 66, when the NPS had resources to spread around.

Protection also improved as a result of the activities of archeologists. Dean worked first at Betatakin, then spent two seasons at Keet Seel. White set up a camp at the outlier for Dean and regarded him as an additional ranger there, "with no salary and at no cost," White later recalled. [42] Someone in residence at Keet Seel, particularly a professional archeologist like Dean, meant that visitors and others were better supervised and educated there than they had been in the past.

The 1970s were dominated by efforts to maintain preservation, largely by controlling the number of visitors to the ruins. These reactive techniques were part of the first comprehensive program for resource management implemented at the monument. Efforts to determine a genuine carrying capacity for both Keet Seel and Betatakin figured prominently in the plans of the monument. The impact had to be considered from more than one perspective. Not only did the park need to find a maximum number of annual visitors, it also needed an individual trip and daily estimate of the number of visitors that could visit without having a significant negative impact on the ruins. Superintendent Frank Hastings undertook the project, regarding it as one of "greatest methods of protecting resources that could have been done." [43]

After the opening of the paved approach road, increased usage made stabilization a constant for administrators at Navajo. Natural wear and tear, human impact, and the need to present the resource to growing numbers of visitors meant an increase in stabilization efforts. Stabilization was carried out at Inscription House in 1977, 1981, and 1984; at Betatakin in 1975, 1981, 1982, and 1984; and at Keet Seel in 1975, 1981, 1982, and 1984. This pattern became an integral part of the process of managing the ruins at Navajo, although the elimination of the Navajo Lands Group limited the monument's access to stabilization resources. By the late 1980s, the only funds available for stabilization was special projects money from the Regional Office. Many parks requested such funding, and there was no guarantee of success for any individual park area.

After the mid-1970s, cultural resource management became increasingly proactive. The Park Service faced a growing demand for its services, and greater development of Navajo land and changes in law assured an increasing amount of archeological work in the Kayenta area. The extensive salvage work performed on Black Mesa typified the nature of such work. Called the "most massive archeological undertaking ever conducted in the region," the Black Mesa Archeological Project had implications for the interpretation of early inhabitation within the monument. [44] At the same time, NPS efforts were directed toward an integrated management plan that addressed preservation issues as well as a host of newer concerns that stemmed from higher levels of visitation, better technology to support collections, and changing perceptions of the function of the park. As yet, no consensus among priorities has been reached.

Yet the integrated approach has had an impact on the direction of NPS preservation efforts. Richard Ambler's archeological assessment of the monument, published in 1985, built on earlier studies and efforts and synthesized them to provide sound management recommendations. Ambler's primary recommendation was the initiation of an intensive archeological survey of the three units of the monument and the 240-acre agreement area. [45]

In the summer of 1988, Scott E. Travis of the Southwest Regional Office undertook the first comprehensive site survey of Navajo National Monument. The survey was designed to rectify prior omissions in the study of the archeology of the monument. Previously unexcavated and unknown sites from the prehistoric and historic periods were located and recorded, providing the kind of baseline data so critical to park management in the 1990s.

The collection of this information represented a major step forward for archeological knowledge and ultimately interpretation at Navajo National Monument. Clearly proactive rather than reactive, Travis's work provided a wide range of information that could become a beginning point. With a broader and comprehensive knowledge of the resources of the monument, the development of management strategies and planning documents took on an immediacy and an importance previously hidden. Finally, the Park Service had the beginning of information with which to create a future for Navajo National Monument.

By the early 1990s, the cultural resources of the monument had a long history that reflected the changing concerns of the Park Service and the archeological profession. Changing authorities and their different concerns affected the disposition of the resources of the monument. From the earliest excavations, museum-sponsored archeologists had a different reason for digging than did the Park Service or other government-sponsored excavators. The NPS in particular was most interested in the structures and the knowledge of them that could be gained from exploration. In contrast, the earliest museum-backed expeditions sought artifacts for collections. With the advent of broader surveys, outside excavators began to ask questions that had implications for interpretation. As visitation increased, its impact became an issue, and when resources became available, the NPS began to perform its own work to support interpretation. This began the process that led to a comprehensive and integrated approach to management of archeology at Navajo National Monument.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

nava/adhi/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006