|

National Park Service

Historic Themes and Resources within the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail Route Southern New Jersey and the Delaware Bay: Cape May, Cumberland, and Salem Counties |

|

CHAPTER 1:

INTRODUCTION

New Jersey, bordered by the Delaware River on the west, New York on the northeast, the Atlantic Ocean on the east, and Delaware Bay on the south, is the fifth-smallest state in the country. Within its 8,204 square miles, however, it boasts a broad range of natural topographical features and retains a surprising balance of urban and rural settings. Despite the proximity to Philadelphia, New York, and the ever-condensing Northeast metropolitan corridor, the lower river and ocean coasts remain pristine. New Jersey has historically acted as a conduit for the growth of its metropolitan neighbors, which represent a market for agricultural and industrial products. Geographer Charles A. Stansfield, Jr., offers the corollary that New Jersey is a microcosm of the United States—with features indigenous to its own industrialized North and agrarian South. It is a unique symbiosis founded on the interaction of land and water. [1]

|

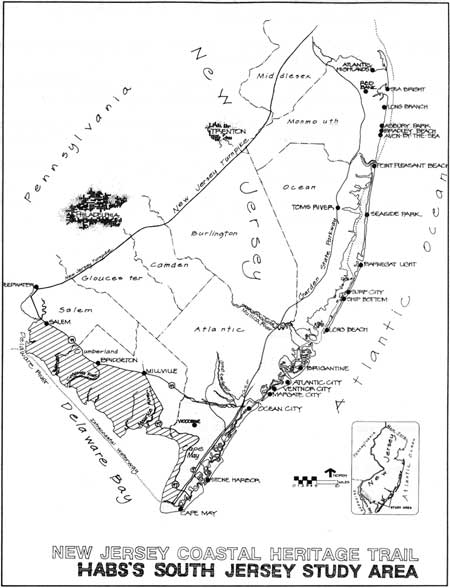

| Frontispiece. New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail and the three-county area of South Jersey studied by HABS in 1990. NPS-DSC. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Through the late nineteenth century, inhabitants of Salem, Cumberland, and Cape May counties depended upon the water for four critical reasons: food, employment, transportation, and energy. Fishermen, whalers, and oystermen reaped abundant shellfish from the salty river beds; goods and produce were transported to Philadelphia markets via boat; and mills flourished along every waterway.

Until the late 1800s when South Jersey was rendered accessible by the railroad, the region was unaffected by the industrial revolution due to labor shortages, few urban centers, and a lack of investment capital, as well as limited access to ports. With the arrival of the railroad, 200 years of dependence upon water travel was drastically reduced. The railroad fueled local prosperity until the early twentieth century when the many industries founded on natural resources began to decline. In addition, an increasing number of automobiles, commercial trucks—and the highways on which they traveled—decreased the dependence on rail and waterways. The combined impact has left South Jersey an isolated, economically static region dependent upon agriculture, tourism, and remnants of once-prosperous maritime and industrial activities. For this reason a variety of architectural and natural resources remain intact, and though some lack a contemporary descendant, others continue to quietly sustain a long and important tradition of agriculture, maritime, and industrial pursuits.

Project Description

The New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail (NJCHT) was established in 1988 to "provide for public appreciation, education, understanding, and enjoyment, through a coordinated interpretive program of certain nationally significant natural and cultural sites associated with the coastal area of the State of New Jersey that are accessible generally by public roads." In its entirety, the region encompasses the area east of the Garden State Parkway/Route 9 from Sandy Hook south to Cape May, and the area north and west of Cape May to the vicinity of Deepwater. [2]

The Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) project during summer 1990 focused on a small portion of the trail, a largely unresearched 450-square-mile area of low-lying land from North Cape May to Salem along the Delaware Bay. It roughly includes all lands south of Route 49 between Salem and Millville, hence south of the Maurice River and west of Route 47 as it descends to Cape May. It is bisected by numerous tidal waterways such as the Maurice River, and Cohansey and Salem creeks, as well as abundant ponds and wetlands that distinguish the state's lacy bayside hem.

Documentation

The four-month HABS reconnaissance study was aimed at identifying significant cultural themes and representative resources, from Indian occupation in the seventeenth century through World War II. This document includes a general overview of the area's history, a list of existing sources for graphic and written historical data, and recommendations for subsequent HABS/HAER documentation by measured drawings, large-format photography, and written history. The themes identified are: transportation, education, religion, social/cultural, and industry with its important sub-themes of maritime and agriculture. The architectural resources affiliated with each are highlighted in the respective chapter, and are the subject of a concluding chapter summing up recommendations for further study. A bibliography of sources includes written material grouped by the same themes addressed in the general context, visual material, general collections and repositories, and those sources that exist but have yet to be tapped.

Physical Description

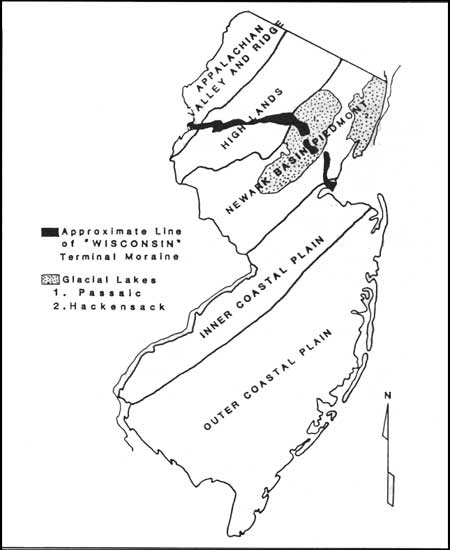

The state of New Jersey, whose only contiguous neighbor, New York, offers a mere 12 percent of its boundary, is otherwise surrounded by water and is best described as a "peninsula of land lying between the Hudson and Delaware rivers." [3] The Atlantic Coastal Plain makes up the southwest area of the state; overall, three-fifths of the state is further subdivided into the Inner Coastal Plain and the Outer Coastal Plain (Fig. 1). The Inner Plain reaches from Sandy Hook across to Salem on the Delaware River; the Outer Plain from Sandy Hook to Monmouth Beach in the extreme northeastern portion of Monmouth County, and from the head of Barnegat Bay to Cape May City. [4] Salem County is within both the Inner and Outer Coastal regions, while Cumberland and Cape May counties are in the Outer Coastal Region. The area resembles most closely the lowland and Chesapeake Bay-fed waters of the Eastern Shore of Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia (called the Delmarva Peninsula). With borders defined by the bay and Atlantic Ocean to the east, the geographic affinities among these locales has spawned common characteristics in architecture as well as cultural and economic development.

|

| Figure 1. Generalized landform regions of New Jersey showing the Inner and Outer Coastal Plains. Geography. |

The soils of the Atlantic Coastal Plain are sandy in the outer region, making farming difficult without augmentation. Coupled with poor drainage, however, a thick layer of organic material is created that is ideal for berry cultivation. Largely made up of flat tidal marshes, swampy creeks, sand dunes, and offshore sand bars, poor- to fair-quality soils here yield vegetables and orchard crops; these are found around the Maurice River and form the backbone of Cape May. [5] The soil along the Inner Coastal Plain is fine, silty—and is some of the most fertile soil in the state. [6] In addition, this area features rolling hills, and pine and cedar forests. Both areas are infiltrated by extensive waterways. These host marine life, flora common to less temperate climates, animals from deer to bald eagles, and mineral deposits of iron, marl, limestone, and sand. Among the 380,516 acres of protected natural environments are the Cape May National Wildlife Refuge, Stone Harbor Bird Sanctuary, Delaware Estuary, Supawna Meadows National Wildlife Refuge, Cape May Wetlands Natural Area, Bevan Wildlife Management Area, and Cedarville Pond Wildlife Management Area. [7]

Methodology

The resources consulted for the preparation of this report include secondary written and graphic material, including county and town histories, newspapers and magazines, commemorative anniversary publications, and texts that address specific aspects of the area, such as the maritime or industrial communities. University and historical society collections offer much in the way of historic photographs and maps. Centennial atlases, Sanborn Fire Insurance maps, and historic U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey maps provided a foundation for the identification and location of many sites. Local residents provide a rich assortment of advice and personal recollection. What remains uninvestigated are many more site-specific primary resources, company records, U.S. Census data, industrial directories, and potentially invaluable oral histories.

Pre-History and Early Settlement

The Lenni Lenape, or Delaware, Indians occupied New Jersey and parts of Pennsylvania, Delaware, and New York an estimated several centuries before the Europeans arrived. Historians and geographers believe that the Indian population was about 6,000, or about twelve to thirty inhabitants per 100 square miles. The peaceful Unami and Unalachtigo tribes lived in the central and southern portions, respectively. [8] The Unalachtigos lived in semi-permanent villages in what is today Salem, Cumberland, and Cape May counties. Permanent villages were few, but they served as important cultural centers. The Lenape founded most of these settlements along major waterways, especially the Delaware River. Three such centers are known to have existed; the one in South Jersey was on the Cohansey River near Bridgeton. [9]

The Indian domicile was the single-family wigwam dispersed around the Big House, a ceremonial structure. Three types of wigwams existed: a circular floor plan with a dome-shaped roof, a rectangular floor plan with an arched roof, and a rectangular floor plan with a gable roof. This framework was secured by saplings tied crosswise over the upright poles. The more permanent dwellings were covered with shingles made from chestnut, elm, cedar or other bark, while the temporary dwellings were covered with woven mats. [10] The Indian village contained other structures, including a "sweathouse," or sauna, as well as gardens and cylindrical pits in which food was stored inside the wigwam.

The Lenape practiced tree girdling and slash-and-burn techniques to clear land to raise corn, squash, beans, rice, sunflowers, cranberries, blueberries, and tobacco; many of these were domesticated by the Indians and later adopted by the Europeans. [11] The Indians not only provided the first Europeans with proof of fertile soil, but their trails provided travel routes. As white settlements increased, however, the Indians were perceived as a growing obstacle. White prejudice, in conjunction with Indian inability to accept private-land ownership, eventually led to the latter's westward migration. [12] Before their departure west, many Lenapes lived on Brotherton Reservation, the first in the United States, established in 1762 in Burlington County. The Indians were provided with European-style houses, a school, store, meeting house, and a gristmill. [13]

In the late eighteenth century, the Lenape remained briefly on the reservation before moving to New York state. By 1822, only forty direct Lenape descendants remained in the area, and they moved to land purchased by New Jersey in Green Bay, Wisconsin (then part of Michigan Territory). This transaction marked the end of New Jersey's ties with the Lenape Indians until recently. Today, Bridgeton hosts a cultural center where visitors can learn about Lenape heritage. [14]

Early European Settlement

Dutch, British, and Scottish pamphleteers encouraged settlers to voyage to the New World in the seventeenth century. The Dutch—the first to arrive in the 1620s—offered the most realistic assessment of the difficulties associated with finding adequate food, shelter, and other basic settlement needs. At that time they owned a considerable portion of North Jersey and New York, then called the New Netherlands. [15]

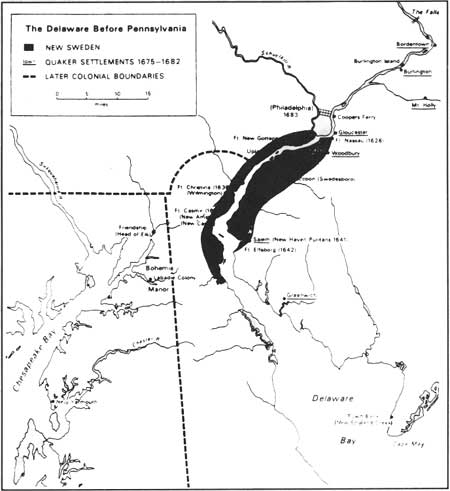

The early seventeenth century also saw Swedish and British settlers arrive, and thus by the 1630s, competition erupted among these three nations for control over the colony. More Swedes arrived in 1635 and attempted to set up a colony near Wilmington, Delaware; the Dutch made the same claim. Meanwhile, fifty English families sailed from England to settle near Varchens Kill (Salem River), which was then part of New Amsterdam (Figs. 2-3).

|

| Figure 2. The Delaware before Pennsylvania, showing late 17th century Swedish and Quaker settlements. Geography. |

|

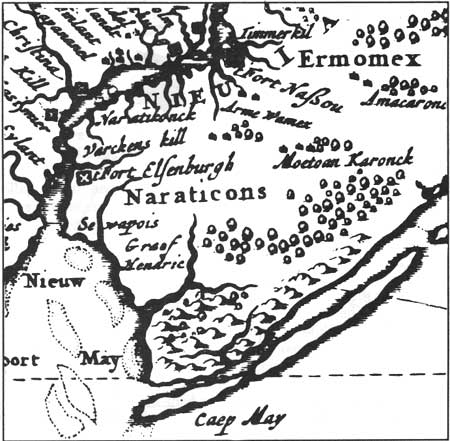

| Figure 3. "New England, New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey in 1685," detail of engraving by Nikolaus Visscher. Library of Congress. |

Conflicting loyalty led the Swedes to construct Fort Elfsborg in 1643 in Salem County; historians disagree, however, whether it was built on the Delaware River side or the Bay side of Elsinboro point. [16] The Swedish effort to gain control of the area was shattered when mosquitoes forced them to abandon the fort in 1652.

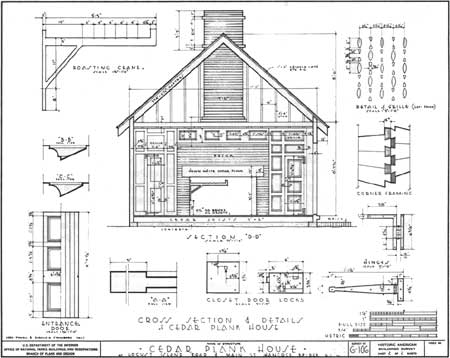

Despite their failure to establish a permanent colony, the Swedes contributed to colonial American architecture. "However, their numbers were so small and their impact so ephemeral that most of the elements were decorative rather than definitive." [17] One original structure attributed to a Swedish origin is the Caesar Hoskins Cabin in Mauricetown. [18] The exact date of construction is unknown, but local historians suggest 1680-1714. In Hancock's Bridge, the Cedar Plank House (ca. 1701), is typical of a Swedish log cabin (Fig. 4).

|

| Figure 4. The Cedar Plank House (HABS No. NJ-106), made of white cedar from nearby swamps, was moved from the Salem-Hancock Bridge Road to Hancock's Bridge; it was documented by HABS in the 1930s. |

South Jerseyans have re-created an example of this heritage based on written literature and artifacts. In Bridgeton, a Swedish log village was erected in 1988 based on American records, archeological findings, and Swedish building technology. Several local historians have also attempted to reconstruct models of the Swedes' Fort Elfsborg; a replica is found in the Salem County Courthouse. Today, the Swedish presence in colonial South Jersey is represented by the aforementioned cabins and the reconstruction in the Bridgeton municipal park.

Permanent European Settlement

The first successful white settlement in South Jersey was established in 1675 by the British. In 1660 King Charles II gave to John Lord Berkeley and Sir George Carteret the colony of New Jersey—East and West, the approximate size of the state today. Thirteen years later John Fenwick, a major in Cromwell's army and a newly converted Quaker, purchased from Berkeley a tract of land that would become West Jersey for £1,000. Fenwick soon was ensnared in a land dispute when Quaker colleague Edward Byllynge claimed Fenwick acquired the land using his money.

The defiant Fenwick, along with a group of fellow Quakers, voyaged to the New World aboard the GRIFFIN, landing near Salem on 23 September 1675. [19] That year Fenwick bought hunting and occupancy rights to land that included Salem and Cumberland counties from the Lenni Lenape Indians in exchange for English goods. Fenwick and thirteen Indian chiefs are popularly alleged to have signed the agreement under the oak tree in Salem's Quaker cemetery. Escape to the New World, however, did not end the problems for Fenwick: Byllynge and two other creditors sought compensation, so Fenwick asked William Penn to arbitrate. Penn met with Carteret to legitimize Fenwick's holdings, which resulted in the Quintipartite Agreement dividing the colony into West Jersey and East Jersey. The division ran from Little Egg Harbor, north of present Atlantic City, to the upper Delaware. [20] In addition, Penn declared that Fenwick did not "own more than one-tenth of the whole of West Jersey, and that the other nine-tenths went to the hitherto defrauded creditors and Byllynge." [21]

Despite Penn's intervention and the agreement, Fenwick still faced creditors and disagreement over the boundaries. Governor Andross of New York jailed him for his claim to West Jersey. In 1682 he sold all of West Jersey to William Penn except for 6,000 acres called Fenwick's Grove, which lies in the present-day Mannington Township, Salem County. Fenwick died the following year, but the colonists continued to be plagued by ownership disputes. As more settlers arrived, however, pressure on the proprietors and governors increased to determine, finally, the borders. Matters were complicated by squatters and land riots. [22] By 1702, Royal Governor Edward, the Lord Cornbury, reunited East and West Jersey under his leadership.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

new-jersey/historic-themes-resources/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 14-Mar-2005