|

National Park Service

Historic Themes and Resources within the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail Route Southern New Jersey and the Delaware Bay: Cape May, Cumberland, and Salem Counties |

|

CHAPTER 2:

URBAN DEVELOPMENT

While the major port cities of Philadelphia and New York developed steadily through the eighteenth century, only the coastal areas of South Jersey saw significant settlement during this period. Access to navigable water and suitable land for buildings provided Philadelphia and New York with the income needed for steady growth. Inland South Jersey areas were not as fortunate, since the waterways were shallow and dependent upon the tides. Salem and Greenwich, however, benefitted from their proximity to the Delaware Bay and were able to compete with major eastern ports well into the eighteenth century. The relatively unaltered character of this area can be attributed to the dominance of its neighbors:

Philadelphia was capital of a region that extended beyond the bounds of Pennsylvania, yet did not quite encompass the entire Delaware basin. West Jersey, where settlement developed in a band aligned with the Delaware, was almost entirely tributary, bound by the convenience of river shipping, the attractiveness of facilities and services, and the lure of the great Quaker center to the many Quakers on the Jersey side of the river. This urban power in Philadelphia dampened the development of towns in all the counties along the river. [1]

Salem County, organized in 1681, first consisted of far-reaching Salem, Cumberland, Cape May, Gloucester, and Atlantic counties. After the American Revolution, Congress declared all land south of Camden as the "District of Bridgetown" so as to establish a customs house—and the tide survived for fifty years. The first collector of customs, appointed in 1789, was Eli Elmer (who later served as postmaster, 1793-1803).

After longtime complaints from residents who had to travel far to attend court or election activities held in the City of Salem, in 1747 Cumberland was created out of Salem County, whose population was then nearly 3,000. [2] Cumberland County court was held in Greenwich the first year, then in 1749 it was moved to Cohansey Bridge (Bridgeton), a more geographically central seat. The first courts met in taverns until the courthouse was completed in 1752. Most of the first judges were laymen appointed by the Royal Governor; also appointed were justices of the peace who served on a board with the elected freeholders. The Board of Justices and Freeholders managed county business, such as establishing taxes used to finance the erection of public buildings. The first such structure was a jail in Greenwich. In 1798 a bill was passed excluding justices from the board while giving Freeholders more power.

In 1683 Captain Cornelius Jacobsen Mey of the East India Company sailed into the Delaware Bay and gave his name to the first area of land he saw—Cape May. Cape May County and its communities lacked the connection to the more developed Salem, unlike Cumberland County settlements. Divorced from Salem County in 1692, Cape May County consisted of 267 square miles about thirty miles long and fifteen miles wide at the north end. In 1878 the present boundary was set, decreasing the county's size by ten square miles. [3] Cape May's individuality stems from its first settlement by Quakers and more important, New England whalers. At first the latter appeared only during the February-to-March whaling season, living in shacks that were abandoned each year. As a temporary settlement this was called Portsmouth; after the whalers became year-round residents, the name was changed to Town Bank. Soon after Town Bank, the communities of Cold Spring and Middletown were established. [4] Cape May County grew so rapidly that by 1723 it was divided into three precincts—Upper, Middle, and Lower—which in 1798 became townships; in 1826 county officials divided Upper Township in half and created Dennis Township. [5]

At times county officials held court in a church or a private home such as in 1704, when it convened at the house of Shamgar Hand who owned 1,000 acres near Cape May Court House. In 1744 the county bought its first court building from a Baptist congregation. Twenty years later Daniel Hand, grandson of Shamgar, deeded one acre of his Middletown (later Cape May Courthouse) property to the county for the site of a courthouse. In 1774 a new court and jail had been built, and in 1803 it housed the second post office in the county. [6] In 1848 Dennisville and Goshen contested the locality of the county seat. After a referendum which favored Cape May Court House (just outside New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail bounds), the Board of Chosen Freeholders declared the latter as the official county seat. Daniel Hand immediately began construction of the third courthouse, which was completed in 1850. The present courthouse was built in 1927. In 1790 the county population was 8,248; by 1860 it was 22,605. [7]

Within the NJCHT portion of South Jersey (Fig. 5) there are three modestly sized cities: Salem, Bridgeton, and Millville. Although these do not compare in size or population to the closest urban hubs of Wilmington or Philadelphia, they are the commercial, industrial, political, and cultural centers for the surrounding towns and countryside. Each contains significant historic, cultural, and commercial resources that are addressed elsewhere in this document. Salem and Bridgeton also serve as county seats, and so contain within their boundaries the major local government offices, as well.

|

| Figure 5. Detail of South Jersey, Evert's illustrated Historical Atlas, 1876. |

The houses of South Jersey reflect a regional Mid-Atlantic cultural pattern as well as later, nationally popular trends. Most eighteenth and early nineteenth-century houses are a two-thirds Georgian townhouse or full center-hall plan. Examples abound of unadulterated Georgian or Federal compositions, in addition to later vernacularized folk Victorian whose ornamentation reflects the financial abilities of the builder-owner. Log or frame with weatherboard or asphaltic siding predominates in this area, and is almost monopolistic approaching Cape May. Brick as a building material is more common in the area west of the Cohansey River in Salem County and western Cumberland County, where the Quakers were responsible for the first permanent settlements—bringing with them patterned brick work.

The mid to late nineteenth-century houses—typically two-story, frame, and single- or two-family plans—are most often Victorian or Gothic Revival, through the addition of some woodwork. The ship's-captain dwellings of the 1860-80s, for instance, feature turned and pierced decorative wood elements on porches, roof lines, and window surrounds; thanks to the strong iron industry, ornate cast verandas and fencing highlight the wealthier homes. Less densely arranged elements of the Italianate and Queen Anne linger on rural dwellings that were refurbished stylistically or gradually stripped down over the decades.

City of Salem

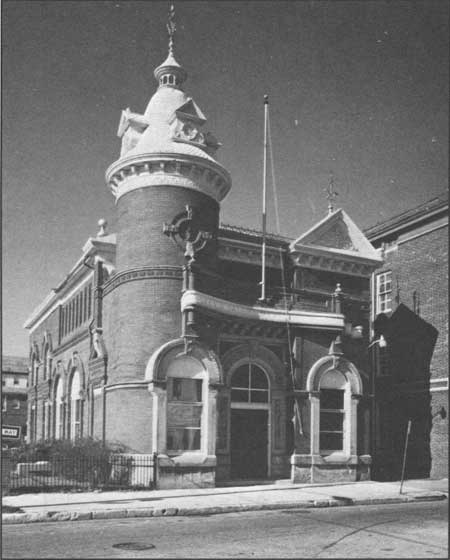

The City of Salem (New Salem), oldest of the three major municipalities, was established by John Fenwick in 1676, and despite his legacy of problems, it prospered as a successful river port through the nineteenth century. One remaining symbol of its early government is the reworked Old Salem County Court house at Broadway and Market streets (1735, 1817, 1908), a two-and-one-half story square brick block laid up in Flemish bond. Salem's eighteenth century Georgian dwellings reflect its foundling Quaker traditions, though the frequency of patterned brick work here is limited to occasional Flemish-bond coursing and dated gable ends. A stunning example of later Queen Anne architecture is found in the Salem Municipal Building (Fig. 6), with its irregular jumble of fish-scale shingles, scrolls, dormers, and elaborate iron weather vanes. The building was moved to its present site from West Broadway at the end of Market Street where New Market Street now opens on to Broadway.

|

| Figure 6. Salem Municipal Building (1899)—with contrasting red brick, stone, and white trim—is exemplary Queen Anne styling. |

|

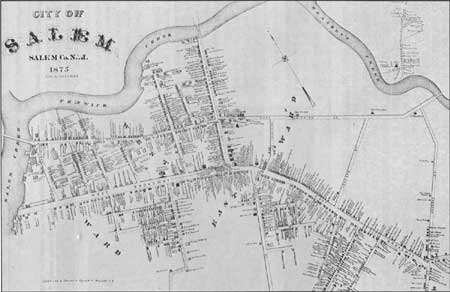

| Figure 7. City of Salem, Atlas, 1875. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

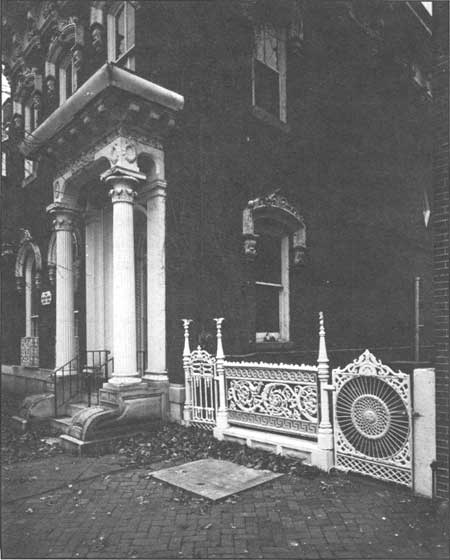

Among the better known Georgian residences are the John Worledge House (1727), with an elaborate horizontal zigzag pattern on the east end, and the Alexander Grant House (1721). The Grant House is among the approximately seventy-six structures included in the National Register of Historic Places's "Market Street Historic District," which suffers little or no intrusion by twentieth-century structures (Fig. 8). Most of these buildings are two-and-one-half or three-story brick houses facing onto Market Street, the historic commercial thoroughfare. The prosperity of the Federal era is represented by formal interiors and exteriors, classical trim, fanlights and fireplaces. Later Greek and Gothic Revival styles are depicted by the use of marble for porch and window trim and gougework in the architraves. The texture of the wealthy Italianate homes extends onto the street by elaborate cast-iron fencing that is produced locally, as in the William Sharp House (1862), for instance (Fig. 9). The housing is punctuated by alleys that once led to the livery stables behind Market Street and the wharves at water's edge.

|

| Figure 8. View of West Broadway, Salem. |

|

| Figure 9. William Sharp House (1862), on Market Street, has 19th-century cast-iron fencing found throughout Salem. |

Not all of Salem's deserving resources are included in the historic district. Along the north and south sides of Route 49 there are fine examples of Georgian rowhouses, as well as Victorian and Gothic Revival structures. The Side streets east of Market Street are lined with examples of two-family double houses, which probably served as worker or middle-class housing in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Their form and features vary: steeply pitched roofs with center gables, or paired gables with decorated vergeboards, pointed-arch windows, or a one-story porch. The Victorian-influenced buildings have one- or two-story bay windows, a mansard or cross-gable roof, and spindlework on the cross gables and porches.

Bridgeton

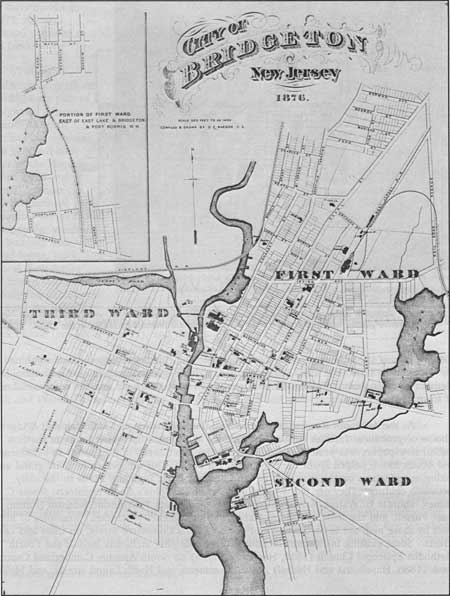

The first Europeans to settle along the Cohansey River included Richard Hancock, a surveyor for Fenwick who bought 500 acres on the east shore and moved there in 1675; within a decade he erected a dam and sawmill. Soon, more settlers arrived, and the town that sprang up on the west side of the river was called Cohansey; the town that grew up on the east side of the river was referred to simply as "The Bridge." Bridgeton was combined and incorporated in 1865 (Fig. 10). Residential and industrial buildings affiliated with the plethora of mills clustered along the river were built near East Lake and the commercial center of town.

|

| Figure 10. Map of Bridgeton, Atlas, 1876. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

As the American Revolution approached, the importance of Greenwich and Bridgeton—home of prominent families such as the Fithians and Elmers—increased. One of the first radical newspapers was printed and displayed at Potter's Tavern in Bridgeton; its sentiments and others like it helped spark the Greenwich tea party. This aristocracy built its grand and exclusive residences on the west side of the Cohansey River from the 1790s to the early twentieth century. They are the work of some of Philadelphia's finest architects: James C. Sidney, Thomas U. Walker, Samuel Sloan, James Sims, John T. Windrim, Addison Hutton, Isaac Pursell, and the team of Edward Hazelhurst and Samuel W. Huckel. Examples of homes built by these men are located along and north of West Commerce Street, on Giles and Lake streets. Some existing institutions attributed to Philadelphia architects include the Fourth Methodist Episcopal Church (1888, Harvey N. Smith) on South Avenue, Cumberland County Bank (1886, Hazelhurst and Huckel) at East Commerce and North Laurel streets, and McGear Brothers Building (1871, Addison Hutton) opposite to the bank. [8]

Many of Bridgeton's significant buildings are part of a designated (discontinuous) historic district encompassing 616 acres on both sides of the river; about 2,000 residential, commercial, and institutional structures are included. The popular materials for building here were wood-frame, brick, and a local New Jersey red-brown sandstone. Among the noteworthy sites are the John F. Ogden House (1813), Jeremiah DuBois House (1833), Timothy Elmer House (1815), Jeremiah Buck House (pre-1808, Fig. 11), and the Samuel Seely House (1798). [9]

|

| Figure 11. Jeremiah Buck House (HABS No. NJ-530), 297 E. Commerce St.—a formal, Georgian block with decorative glazing, shutters, dormers, and porches—was documented by HABS in the 1930s. HABS. |

Approximately 80 percent of the residential architecture in the historic district is the double house whose gable-front earned it the local name, "A-Front Double." This type is found elsewhere in town, as well. Often close to an industrial facility, they typically were built and shared by factory workers who occupied one half and rented out the other:

Size of family and financial circumstances do not seem to have made a difference in the building of doubles except in scale and extent of architectural detail. A glass factory owner was just as likely to share a party wall as were the workers in the factory. The double house can be seen as a symbol for a city whose success was derived from the willingness of the rich to invest in the town and from the acceptance of mutual dependence. . . . [10]

Another common residential form is the saltbox, introduced by settlers from New England. Most houses in Bridgeton are ornamented with a smattering of vernacular design elements from Greek Revival, Queen Anne, and Stick Style—some manage only dentil molding, while others tout Victorian turrets, projecting bays, and grand mansard roofs with decorative shingles. [11] Little major alteration has been made to Bridgeton's historic core since the early twentieth century.

The city's role as the county seat is represented by the nearby Cumberland County Hospital (Fig. 12), an outstanding Palladian block both in its monumental scale and elaborate Georgian detailing. The layout is a bilaterally symmetrical seven/nine-part plan with hyphens and projecting blocks. Fine Georgian details include five cupolas, a rusticated, raised foundation, and round-topped windows with decorative glazing. Of practical note, the rear facades are equipped with metal tube-like chutes that drop from the second floor down to the ground; in case of fire, patients could slide down them to safety. On the interior, the foyer features a similarly Palladian octagonal rotunda with arched openings supported by Doric columns; though currently unoccupied the building appears to be in good condition.

|

| Figure 12. Cumberland County Hospital (1899), a massive Georgian Revival building composition, is one the most formal in the area and currently unused. |

Bridgeton has commemorated its heritage with a reconstructed Swedish farmstead located in the municipal park on the west side of the Cohansey River. Opened in April 1988, the New Sweden Company Farmstead Museum consists of seven reconstructed seventeenth-century log structures, among them a dwelling, smokehouse, threshing barn, bath house, and animal shelters. Next to the museum is a reconstructed Lenni Lenape Indian village of tepees. The Indian village is complemented by the George Woodruff Museum in the Bridgeton Public Library, and the Lenni Lenape Information Center on East Commerce Street.

Millville

Prior to the founding of Millville, Henry Drinker and Joseph Smith purchased 24,000 acres of woodland here, built a dam, and formed the Union Company whose main product was lumber cut at the water-powered sawmill and floated downriver. In 1795 Joseph Buck, a Cumberland County resident and Revolutionary War veteran, bought a portion of the Union Company land and planned Millville. The town was laid out to facilitate the erection of mills on every possible tract along the river, with manor houses situated on higher ground to the east. His plans show streets extending from Smith to Broad streets, and from Buck to Fourth streets along the river. As Buck planned, Millville's first residents established themselves on the east side of the river, though as more people settled there, houses were built on the opposite shore, too (Fig. 13). Millville was incorporated in 1866.

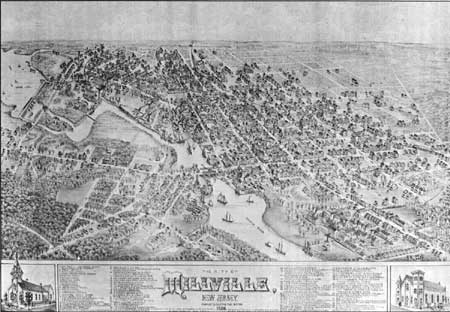

|

| Figure 13. Bird's-eye view of Millville, (1886). Wettstein. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Millville resident Charles K. Landis purchased a large tract of land that included the land north of the dam that had once been owned by the Union Company, and extended into Gloucester and Atlantic counties. In 1862 Landis laid out the town of Vineland about two-and-one-half miles east of the Maurice River and seven miles north of Millville. In 1864 Vineland was separated from Millville Township and became part of newly formed Landis Township. Since then, Millville Township (which was divided from Fairfield and Maurice River townships in 1801) has consisted only of the town of Millville. Vineland, while historically connected to Millville, is outside the NJCHT study area.

Dwellings on the east side of Millville exemplify Buck's ideal of an integrated residential-company complex and reflect a variety of nineteenth-century architectural styles. The Richard Wood Mansion (1804), made of South Jersey sandstone, was built by David Wood who, along with Edward Smith of Philadelphia, bought the Union Company improved the dam, which they used to power a blast furnace.

The mansion is flanked by blocks of houses that were rented to Wood company employees. These are either plain, two-story double A-Fronts with four bays across, or boxier three-story, three-pile, six-bay dormitory-like buildings with two ridge chimneys. Entrances are in the third bay of the side facade, or centered in the gable end. Few of the latter, especially, are decorated; on the ones that do contain ornamentation, it is usually limited to spindlework on the porch. Present occupants have restored the buildings' exterior with aluminum or faux-brick asphalt siding—perhaps to help establish their identity in the neighborhood.

Double dwellings on close-by Archer Street reflect late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century middle-class origins. These gambrel-roof, gable-front, double piles appear to be a bilaterally symmetrical plan. A total of six bays across, the recessed entries are in the outermost bays. One-story porches that wrap around the facade from door to door, and hipped-roof dormers, are common; others have a pent or visor instead of a porch. [12] Elsewhere in Millville, worker's housing is found near the Foster-Forbes Glass factory aligning both sides of Route 47 at the south end of town, and on the west side of the river on both sides of Route 49. These, too, are double-A types, though the ornament is more Victorian, akin to buildings in Bridgeton and Salem.

Millville's refined and eclectic Victorian upper-class housing is mostly located on the northeast side of the Maurice River between Pine and Oak streets, on either side of Route 47/Second Street. Their ornamentation reflected the prestige assumed by the occupants. Second Empire and Italianate design features predominate, with mansard roofs and deep eaves, scroll-based window surrounds, tall rounded or pointed windows, steep patterned roofs with elaborate brackets, bays, and spindlework porches. The Gothic Revival styles have pointed windows, cross gables, and steeply pitched roofs. Examples include the Edward Stokes house (ca. 1870), Second Street between Mulberry and Pine, home of a Millville native who served as governor 1904-08. The Smith-Garrison Ware House (ca. 1850), opposite the Stokes house, was home to Robert Pearsall Smith, manager of Whitall Tatum Company and founder of the Workingmen's Institute. The Isaac Owen House (1854), South Second Street, was built and owned by a Port Elizabeth carpenter who constructed the Union Lake Dam, Millville Bank, and other structures in Millville. [13] The historic commercial thoroughfares are High Street (Fig. 14), Main Street/Route 49, and Second Street Route 47.

|

| Figure 14. View of High Street, Millville. |

Small Towns

The small towns that depend on Millville, Bridgeton, and Salem for major services also have significant architectural structures, though they are fewer and less densely placed. Most are adjacent to a waterway, or are located along a main road or street that intercepts the water. While some of these quietly picturesque hamlets are obvious candidates for historic designation, other settings must be determined through research.

Like many towns founded along rivers and creeks during periods of early settlement everywhere, these share a pattern of street names associated with the proximity to shore and its landmark buildings. High Street, Water Street, Front Street, and Mill Street usually indicate the route closest to the water; and Main Street runs perpendicular to them. In Millville, Dorchester, Mauricetown, Salem, and Hancock's Bridge, after High or Front Street logically comes Second Street. Commerce and Market streets, often lined with non-residential structures, are near the water as a testament to the importance of transportation and trade. More common names—sometimes denoting a structure or location—include Church, South, Washington, and Union streets. Indicative of historic function are Port Street in Dividing Creek, Stable Street in Port Elizabeth and Mauricetown, and Temperance Street in Port Norris.

Of the three counties, Cumberland has by far the most small towns in the area designated for study; Greenwich, Roadstown, and Fairton are the oldest. While a handful of these continue to function as well-preserved historic towns, most saw their heyday in the prosperous and populous industrialized years of the nineteenth century, and have since shrunk in both economic and physical terms.

Salem County

Hancock's Bridge

Salem County encountered more Revolutionary War action than its neighbors, and so had its own militia. The first contest was in May 1776, with the British warships ROEBUCK and LIVERPOOL chasing the American brig LEXINGTON on the Delaware River. The local militia, the Associators, helplessly watched while the battle was lost. Salem encountered the British again in winter 1778, when George Washington and his troops were in desperate need of food at Valley Forge; residents provided cattle and supplies. In retaliation, the British initiated the Salem Raid along the American defensive line at Alloways Creek, where there were strongholds at three major bridges.

|

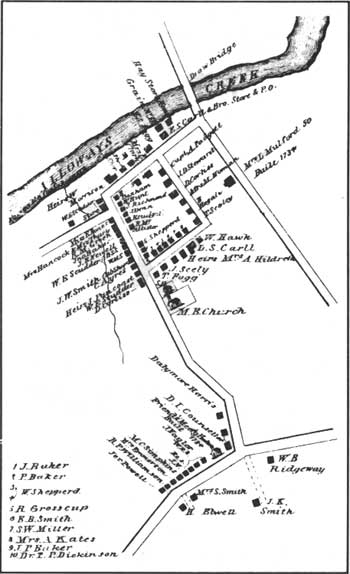

| Figure 15. Map of Hancock's Bridge, Atlas, 1876. |

The first of two battles occurred at Quinton's Bridge, 18 March 1778, when the British discovered American forces had crossed the bridge. Colonists retreated with the British in pursuit and, coupled with reinforcements, the defensive line was sustained. The British then turned to destroy the line at Hancock's Bridge. Stationed at the nearby William Hancock House were thirty Quaker volunteers who cleverly removed the planks from the bridge every night to keep the British from getting across. A group of Tories sailed to the mouth of Alloways Creek, however, then marched across the marsh to Hancock's House while more British troops guarded the opposite bank of the creek. The Redcoats pursued and brutally massacred all the men; the American line was destroyed and the emplacements abandoned. The British thereafter departed South Jersey until the War of 1812. [14]

Today Hancock's Bridge is a small hamlet comprised of predominately nineteenth-century houses (Fig. 15). The William Hancock House (1734) is still extant and is part of the state park system. In addition to being a Revolutionary War battle site, it is also the home of one of the area's oldest Quaker meeting houses (1754, 1784). In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, many residents worked at the Carll and Brown Creamery or Fogg and Hires Cannery. Many area farmers brought their produce here for shipment to urban markets. [15]

Harmersville-Canton

Just south of Hancock's Bridge are the two crossroads villages of Harmersville and Canton. In the late eighteenth century, Quakers from Hancock's Bridge established a cemetery outside of Harmersville on the road to Canton; many victims of the Hancock's Bridge massacre area buried here. Today the cemetery belongs to the Canton Baptist Church.

Canton, below Harmersville, was at one time a bustling town thanks to the Shimp and Harris and H.J. Smith tomato canneries that operated during the early twentieth century. With a population of 150 in 1909, Canton, like Harmersville and Hancock's Bridge, relied upon Salem for banking and other services. Canton, however, had a post office and a public school. [16]

Pennsville

Historians credit the settlement of Pennsville—the principal town in Lower Penn's Neck Township—to the Swedes and Finns. Under the direction of the New Sweden Company, the first Swedes attempted to set up a colony in West Jersey in the early seventeenth century. Simultaneously, in Europe the Swedes had gained control of what is present-day Finland. As a result, the company encouraged Swedes and Finns to immigrate here, and it is believed there was a Finnish settlement at the site of Pennsville as early as 1661. By 1685, their settlements in the Lower Penns Neck area were acknowledged by English map makers, and Finns are cited as the "earliest citizens of New Sweden to occupy the land between Salem and Raccoon Creeks." [17] St. George's Episcopal Church, on the west side of North Broadway/Route 49, is symbolic of these Swedish Lutheran roots, because residents later adopted Episcopalian practices and theories. Although the date of the congregation's founding is unknown, a church at this site dates to ca. 1714; the present structure was erected in 1808.

The nineteenth century was a period of growth for Pennsville. As early as 1800, a ferry was established between here and New Castle, Delaware. Over the next forty years, Pennsville had a stage connection to Salem and elsewhere, several hotels, a store, wharf and a grain house as well as dwellings. As Pennsville continued to develop, it became a stop for steamships from Philadelphia en route to the Delaware River resorts. [18] Riverview Beach amusement park boasted rides, a carousel, and a beach with dance halls, bathing and boating facilities, and a hotel. One-story frame bungalows are found along streets named Beach, River, Lakeview, Water, Springside, and the west side of Broadway that belie their connection to Riverview and Brandriff beaches. Today Riverview exists not as an amusement park but as a municipal park.

Pennsville was also home to Fogg and Hires Company Canning Factory, which operated on a seasonal basis, at a factory just off Main Street a few blocks from Riverview Beach. In the early twentieth century Howell and Wheaton had a factory where caviar was cured and packed. Shad fishing was also popular during April and May but there are no physical remnants of this industry. The 1909 Industrial Directory touted Pennsville as an ideal site for enterprises needing water transportation because of its wharves and low tide that never fell below 10'. [19] Moreover, its proximity to Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Salem was attractive.

Quinton's Bridge

Located on Alloways Creek east of Salem, Quinton's Bridge was an early eighteenth-century settlement and a battle site during the Revolutionary War, as previously mentioned. The town's location on the creek made it a prime spot for nineteenth-century industrial endeavors. Quinton's Bridge boasted three major industries in the late 1800s: Harry Ayres Cannery, which employed 100 persons; Fogg and Hires Company, which employed 200; and Quinton Glass Company, with a roster of 150 workers. The town also had shipwrights and gristmills, as well as several stores, two public schools, and Baptist and Methodist churches. [20] Today the town consists of nineteenth-century dwellings of different styles and ornamentation. Some of the housing associated with Hires, Prentiss is still extant along the east side of Alloway-Quinton Road. The only industry left in the town is Smick's Lumber, located on the site of the Quinton Glass Company.

Cumberland County

Cedarville (Cedar Creek)

Situated on both sides of Cedar Creek, a tributary of the Delaware River, Cedarville is four miles from Fairton and eight miles from Bridgeton. The first white explorer believed to have seen the creek was Captain Samuel Argall, captain of the DISCOVERY, which sailed up the Delaware Bay in 1610. In the late seventeenth century, Cedarville was home to such great men as Drs. Jonathan Elmer and Ephraim Bateman, both physicians and congressmen. [21]

Cedar Creek was renamed Cedarville in 1806 with the establishment of a post office. Throughout the nineteenth century the town grew with the development of local industries founded on the locale's natural resources: bog iron, sand, water power, and fertile land. In the early twentieth century, Cedarville was home to three canneries: W.L. Stevens and Brothers, J.E. Diament Company, and Fruit Preserving Company, as well as the Crystal Sand Company. [22]

Nineteenth-century prosperity allowed residents to erect fine homes. Although many are vernacular, others express a Victorian love of ornament. An example of this is the Padgett Funeral Home (Fig. 16), a squarish Italianate form with a flat roof, brackets and cupola.

|

| Figure 16. Padgett Funeral Home (19th century) is characterized by its boxy tines, flat roof and Italianate detailing. |

Dividing Creek

The first settlers to the Dividing Creek area probably came from Fairfield in the early eighteenth century; Baptists were here before 1749. As early as 1763 a bridge was erected over Dividing Creek, for which the town was named, near where it divides into several branches. [23]

In the nineteenth century many Dividing Creek residents worked in the oyster industry. In 1881 a marine railway for the repair of oyster boats was opened by John Burt, George Sloan, and M. Howell. In the early twentieth century, the most substantial extant industry was M.J. Dilk's sawmill. In addition to general lumber products, Dilk made peach and garden truck baskets. [24] The prosperity of the last century made Dividing Creek a stop on the Central Railroad of New Jersey and a switching station for the Bridgeton and Port Norris Electric Trolley Company. The trolley cars ran along Main Street, perpendicular to the creek. Most houses are vernacular, located on the west side of the creek, and were erected in the nineteenth century. Also in place is a Baptist church, organized in 1755, and a Methodist church of 1830. [25]

Dorchester

Located along the Maurice River about three-and-one-half miles from Port Elizabeth, Dorchester was part of an early survey undertaken by John Worledge and John Budd in 1691. In 1799 Peter Reeve bought part of this land, laid out Dorchester, and sold lots. [26]

During the nineteenth century, shipbuilding was the principal occupation of townspeople, at two yards: Blew and Davis, and Baner and Champion. The latter was rented to the Vannaman Brothers of Mauricetown in 1882; they constructed large three-masted schooners here. At the turn of the century, the shipyards were operated by Charles Stowman and Son, and John R. Chambers.

In 1882 a post office was established in Dorchester. The extant housing stock is nineteenth century—the ornate ones reflect the talents of resident shipwrights. Today, a minimum of shipbuilding activity is ongoing. [27]

Fairton/New England Town

More of a locality than a town, New England Town is on the east side of the Cohansey River. The first settlers arrived from New England in the late seventeenth century, and evidence of their presence is found at the site of the first Fairfield Presbyterian Church and graveyard, on Back Neck Road just off Route 553. In 1780 the church site was moved, and the congregation built the Old Stone Church. [28]

Considered locally as part of the area called Fairton/New England Town, this village boasted gristmills and sawmills throughout the eighteenth century. Fairton gained its name in 1806 when a post office was established here. Throughout the nineteenth century it grew to became a cultural center for the surrounding farmers. Like other Cumberland County towns, many men worked in the oystering industry, in addition to Furman R. Willis's beef and pork packing house, Richard M. Moore Glass Company, Whitaker & Powell canners, and Crystal Lake Milling Company. [29]

The mid to late nineteenth-century houses in Fairton reflect its era of growth and development. Little has changed today, with the houses along Route 553 remaining primarily intact. The town is associated with a local marina as well as nearby farms.

Gouldtown

Gouldtown, located about two-and-one-half miles east of Bridgeton on Route 49, was founded as a mulatto community. According to local tradition, the Gould family were mulatto descendants of John Fenwick. His grand-daughter, Elizabeth Adams, allegedly married a black man named Gould. Upon his death, she inherited 500 acres from whence Gouldtown was established. Benjamin Gould—who may or may not have been Elizabeth's son—then founded the town. [30] When Gould reached the area he bought 249 acres, making him one of the first blacks to own property here.

In 1820 a Methodist society was formed in the town, and in 1861 a church and school were built; in 1873 a post office was established. Several regionally prominent men who came from Gouldtown were descendants of its founder, among them Theophilus G. Steward, U.S. Army chaplain and writer; William Steward, newspaperman and an author; Bishop Benjamin F. Lee, president of Wilberforce University in Ohio; and Theodore Gould, presiding elder in the Philadelphia Methodist Conference. [31]

Today the town is a crossroads on Route 49 between Bridgeton and Millville with a church and a school. Many of the structures were built in the twentieth century.

Greenwich

|

| Figure 17. Map of Greenwich, Atlas, 1876. |

In 1683, shortly before John Fenwick died, he undertook plans for a town called Cohansey on the river of the same name. Ye Greate Street was surveyed in late 1683, and in February 1684 the first lots in Greenwich (Fig. 17, pronounced Green-witch) were sold; Fenwick willed the first two lots to his friend Martha Smith. The first settlers in the town were Quakers and Baptists, and in addition to being a farming community, maritime activities led it to be named a port of entry in 1687. [32] Named after Greenwich-on-Thames, the village today is a well-preserved colonial hamlet with all its structures (1686-1918) listed in the National Register of Historic Places district—which encompasses Ye Great Street to the village of Othello. A monument in town commemorates one significant event indicative of Greenwich's early importance.

In December 1774, shortly after the Boston Tea Party, the brig GREYHOUND arrived in Greenwich loaded with tea. The captain feared that if he attempted delivery to Philadelphia the cargo would be burned, so he hid it in the home of English sympathizer Dan Bowen. The majority of the county chose to support the Continental Congress's decision to resist taxation without representation, however. Enraged Greenwich citizens learned of the hidden tea, and on 22 December, whites disguised as Indians captured and burned it in Greenwich's town square. Among the participants were Richard Howell, Philip Vickers Fithian, Andrew Hunter, and Ebenezer Elmer, who subsequently served in the revolutionary ranks. The tea party was a major event in Cumberland County during the war.

Among the many fine examples of patterned brick work in Greenwich are the Nicholas Gibbon House (1730), Richard Wood Mansion (ca. 1795), Vauxhall Gardens (1698), and Bowen House (1765). [33] Many buildings in town were recorded by HABS/HAER in the 1930s.

Haleyville

Located one mile west of Mauricetown, Haleyville consists of a series of primarily nineteenth-century vernacular houses on either side of Route 676. Its agriculture-based community centered around the Methodist church, established in 1810. At mid-century, the town erected and supported a public school. Both structures are extant today, though the school is used as the office of a cable company. A post office was established in 1873, but it no longer exists.

Heislerville

As early as 1800, the people who lived in this area met in the local school for church services. In 1828 an Methodist Episcopal Church was organized here, and the Heisler family was a prominent element of the congregation. The town, named for them, grew during the nineteenth century. [34] Many residents were watermen, as the town is located where the Maurice River enters the Delaware Bay. Much of the commercial activity consisted of oystering, with limited vegetable and berry farming. [35] In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Heislerville's population rose from 100 to 450; at that time a post office was established, and the West Jersey and Seashore Railroad (Maurice River Branch) passed within one mile of the town.

Today the town is a modest crossroads village en route to East Point Lighthouse. One impressive Gothic Revival house (Fig. 18), at the corner of Main Street and Glade Road, reflects the prosperity that once existed here. This mid to late nineteenth-century dwelling may have been a stage stopover. Its location is critically close to the East Point area, which served as a resort complete with hotel and restaurant; the hotel, located west of the lighthouse, burned in 1900. [36]

|

| Figure 18. This Heislerville house (19th century) has fine Victorian elements in its pointed Gothic windows, gables, and spindlework trim; a store was in the rear. |

Jericho

Located on the southeastern side of Stow Creek, the dividing line between Cumberland and Salem counties, the land that became Jericho was purchased in 1680 by John Brick. He and his family were the first settlers in the area, and established gristmills and sawmills. As time progressed, Jericho developed as a location on the road from Bridgeton to Salem via Roadstown. [37]

John Wood, mill owner and entrepreneur, attempted to increase the importance of Jericho during the early nineteenth century; in 1818, as a partner with New York businessman John E. Jeffers, he opened a woolen mill. Jeffers backed out of the project, however, and the machinery was sold in 1830. In 1883, the town had less than 100 residents and no major businesses. [38] Today Jericho is a crossroads off of Route 49.

Leesburg

The land that later became the town of Leesburg in the late eighteenth century also was surveyed by John Worledge and John Budd in 1691. Similar to Dorchester, the first settlers to the area were most likely Swedish, though a town was not established until 1795 when John Lee, an Egg Harbor shipwright, founded Leesburg. In doing so, he and his brothers opened the first shipyard—and with it established the industrial destiny of constructing coastal vessels. In 1850 James Ward built a marine railway here to facilitate the repair of larger ships, which were attracted to Maurice River site because it was only six miles from the Delaware Bay. [39]

Though Leesburg's economic base was primarily shipbuilding, two successful early twentieth-century industries were the Leesburg Packing Company, a cannery that seasonally employed 100 persons, and J. C. Fifield and Son, a fertilizer works. Today the only evidence of these industries is WHIBCO Inc., a sandmining company whose administrative offices occupy the buildings of the former Del Bay Shipyard (Figs. 26-27). [40]

Mauricetown

Prior to the 1880s when the oyster industry boomed in Port Norris, Mauricetown (pronounced Morris-town) was the largest and most active center in Commercial Township (Fig. 19). In 1780 Luke Mattox bought land, constructed a landing, and called the area Mattox's Landing. He and others shipped cord wood and lumber from the wharves along the river. In 1814 the Compton brothers bought land here, platted out a town, sold lots and erected houses. By then it was called Mauricetown, due to its riverside location, and as such became the home to several shipyards. One of the first belonged to Joseph W. Vannaman and the captains of ocean-going schooners. The latter dealt some in the oyster trade, though they were more likely to have been associated with shipping lumber and other goods.

|

| Figure 19. Mauricetown, named for its Maurice River site, is composed of well-preserved structures that deem it worthy of listing in the National Register. Wettstein, ca. 1950s. |

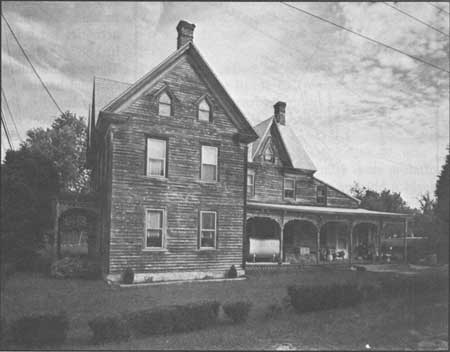

In the mid to late nineteenth century, Mauricetown was known for its population of wealthy sea captains. The grandeur of their Italianate or Gothic Revival-style houses reflects the craftsmanship and lucrativeness of the industry—and the houses remain more often than not virtually intact. The most ornate examples parallel the river on Front Street, including the Ichabod Compton House (1812, Fig. 20), the Captain Samuel Sharp House (ca. 1860), the Captain Maurice Godfrey House (ca. 1870) and the Captain Charles Sharp House (ca. 1860).

|

| Figure 20. Ichabod Compton (1782-1833), a descendent of the founders of Mauricetown, a waterman and sawyer, lived in this dwelling. |

Today, the collection of dwellings, churches, and a school are uninterrupted by modern intrusions. Mauricetown possibly warrants listing as a National Register of Historic Places district.

Newport

Located below Cedarville, Newport sits on the south side of Nantuxent (Autuxit) Creek. The earliest record of settlement here is the will of William Mulford, 28 July 1719, which refers to his plantation on Autuxit Creek. By the middle of the eighteenth century, the town had a hotel, sawmill, and gristmill—the latter located on Page's Run, a branch of the creek. The town got a post office in 1816. The oyster industry employed many Newport men in the late nineteenth century who, like wealthy Port Norris residents, built Victorian homes or "modernized" existing dwellings. Today these remain a symbol of the last century's prosperity. [41]

Othello/Head of Greenwich

This village is essentially the northern extension of Greenwich's Ye Greate Street, and features a Quaker meeting house and Presbyterian church. Built in the 1830s, the former was home to the Hicksite Quakers who broke from the Orthodox sect in Greenwich. The Presbyterian church was organized prior to 1747; the present Greenwich Presbyterian church appears to have been built in 1835. One prominent Presbyterian from this area is Philip Vickers Fithian, a Princeton graduate and minister. Like Greenwich, the structures in Othello date to the eighteenth century.

During the late nineteenth and the early twentieth century, Othello was the site of the Pennington Seminary, a large private school that attracted boys and girls from all over the county. Industries here included: the Union Boiler Company, which employed eighty men, and the Pennington Cannery, with a work force of forty men and women during canning season. [42]

These historic homes and structures are listed on the National Register as part of the Greenwich Historic District. Two more important resources are the cemetery associated with the Presbyterian church and a cemetery just north of here that contains the graves of several black Civil War veterans.

Port Elizabeth

Port Elizabeth, on the Manamuskin Creek, a tributary of the Maurice River, was one of the first Cumberland County settlements established as early as 1750. In 1771 the land on which the town is located was bought by Elizabeth Bodley, after whom it is named. She then laid out streets and lots and began to sell them; the first lot was deeded to the Methodist Episcopal Church. During the late eighteenth century, the town became a port of delivery, where duties on foreign imports were collected. At the same time, the town acquired its first hotel and a road was built to Tuckahoe, with Port Elizabeth serving as the eastern landing of the Spring Garden Ferry, which linked the east and west banks of the Maurice River. [43]

The first entrepreneurs here were James Lee and his half brother Thomas, both of Chester County, Pennsylvania. In 1801 the Lees established a factory for the manufacture window glass. Ownership of the works changed hands several times throughout the nineteenth century and it was closed by the early twentieth. By 1850, however, the town included a post office, school, and three churches. Many of the dwellings reflect the town's development in the middle to late nineteenth century. As with most area towns, the houses are vernacular with little ornamentation. [44]

Port Norris/Bivalve

See Chapter 3: Maritime.

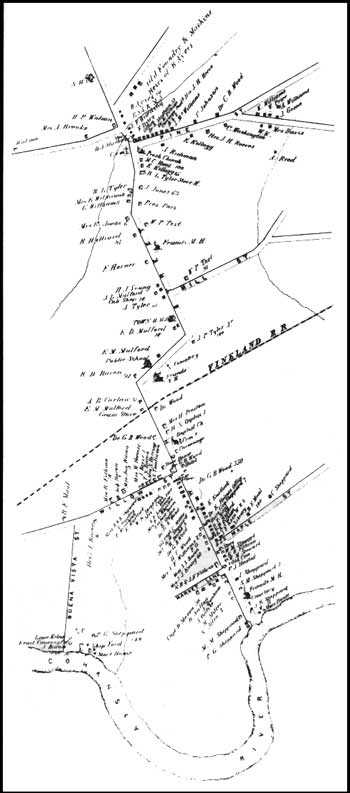

Roadstown

An early stop on the first stage lines between Greenwich and Camden, and Bridgeton and Salem, Roadstown was first called Kingstown; later it was known as Sayre's Cross Roads, after Ananias Sayre, a prominent citizen and county sheriff. Since the early nineteenth century it has been called Roadstown (Fig. 21). [45] Settled by the British in the early seventeenth century, Roadstown ranked in importance next to Greenwich, Fairton/New England Town, and Bridgeton/Cohansey's Bridge.

|

| Figure 21. Roadstown is the site of the Ware chairmaking family as well as several patterned brick houses. |

Today the town is noteworthy for two reasons. First, it was the home of the Wares, a multi-generational family of chairmakers whose ladderback, rush-bottom chairs are now highly valued among collectors. It is also an area rich in patterned brick houses with their construction dates and builder's initials in the gable. Included among these are the David Bowen House (1770), Ananias Sayre House (1770), and Daniel Bowen House (1775); just outside of town on Route 626 is the John Remington House (1728). [46]

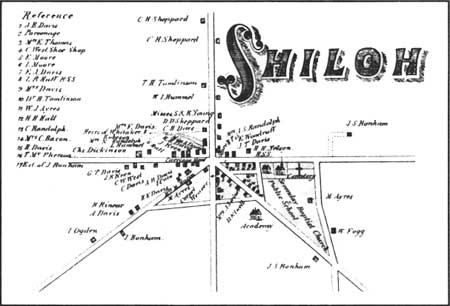

Shiloh (Cohansey Corners)

The town of Shiloh lies in Hopewell and Stow Creek townships on property that was part of a survey by Dr. James Wass, and in 1705 was bought by Robert Ayers, a Seventh-Day Baptist. He laid out lots and sold them to other Seventh-Day Baptists; the town has remained affiliated with this sect, and the history of the church coincides with that of the area. The church was organized as early as 1737, and Shiloh became the nucleus around which these Baptists gathered (Fig. 22). [47]

|

| Figure 22. Map of Shiloh, Atlas, 1876. |

In 1841 a post office was established here. The Union Academy opened in 1849 with a curriculum oriented toward agricultural teachings. The industrial focus of the town mirrored the area's agricultural importance. In the late nineteenth century, several canneries employed residents, including that of Davis and Rainear, which operated in this century. [48]

Today, Shiloh's structures depict a once-bustling crossroads. At the intersection of Routes 49 and 696 there are two general stores and a service/gasoline station. The houses, however, reflect the heyday of community, having been erected in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The academy building is extant, as is the DeCou's Farm Market and Packing Business, which operates at the east end of town.

Springtown

Springtown is in the northeastern part of Greenwich Township along the Greenwich-Bridgeton road. The community was founded in the nineteenth century as a haven for runaway slaves from Maryland and Delaware. That Springtown began as a haven for fugitive blacks distinguishes it from other area black-settled communities such as Gouldtown and Bridgeton. The town gets its name from a former slave, possibly Andrew Springer, who arrived here in the early nineteenth century with other runaways. The Quakers of Greenwich encouraged them to form their own community. Once it was established, Springtown may have been a stop along Harriet Tubman's Underground Railroad. [49]

By the twentieth century, the number of residents had declined such that the town could not support its three schools; only one survived in 1908, with fifty pupils. The three churches in town had so few members that they could not form a full congregation. The falling population was a result of the black migration to cities—Bridgeton, Philadelphia, Wilmington, New York—in search of work. Today there is little left of Springtown except for a few houses, the Wesley Methodist Episcopal Church, and the Bethel AME Church. [50]

Cape May County

Cold Spring

Cold Spring, established as early as 1688, gets its name from the freshwater spring that bubbled up through the salt marsh. Indians used the water for years, and passed on its value to the Europeans. The "cool spring water was retrieved by lowering a corked bottle into the spring, then pulling the cork out allowing the bottle to fill with fresh water." Prior to the early 1800s a shed covered the spring; this was replaced by a series of nineteenth-century gazebos that burned. [51]

During the early eighteenth century, the land Jacob Spicer owned around the spring was also the site of his plantation. After the community developed it became a stagecoach stop. In the early eighteenth century Cold Spring Presbyterian church was organized, and in 1718 a log church was constructed. The present brick church on Seashore Road was built in 1823; five years later the Cold Spring Hotel opened between Cold Spring and Cape Island. In 1857 the Cold Spring Academy was founded under the direction of Reverend Moses Williamson. This was the first school in the county to teach high-school level courses. Today, of these buildings only the church is extant. The spring, located in an obscure place along Route 9, is still active and is witnessing the construction of a new gazebo. [52]

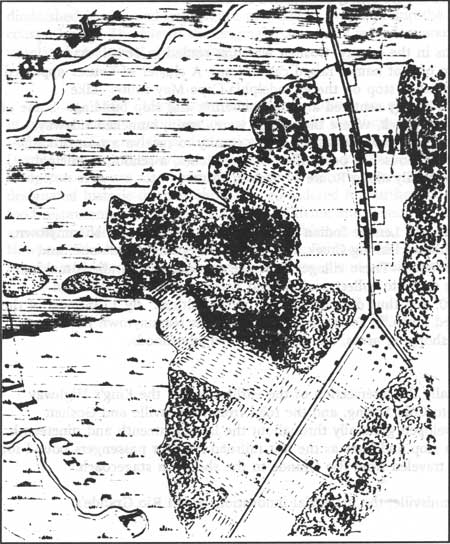

Dennisville/North Dennis/South Dennis

The areas that today consist of Dennisville, North Dennis, and South Dennis were collectively known as Dennis Creek until the second half of the nineteenth century (Fig. 23). Dennisville/Dennis Creek was deeded to John Dennis after he purchased the land from an Indian named Panktoe in 1687. Sometime between the 1690s and 1726, Jacob Spicer owned the land; in 1726 he sold it to Joseph Ludlam. Ludlam's sons, Anthony and Joseph, settled on both sides of the creek, and the foundations of the town were in place. [53]

|

| Figure 23. Map of Dennisville. US. Coast Survey, 1842. |

Industrially, Dennisville is known for two things: lumber and ship building. Many residents mined cedar trees out of the local swamps. The trees were cut for siding and shingles—much of which was exported via schooner. Among the lumber mills that existed in the early twentieth century were those of Ogden Gandy, Jesse D. Ludlam, and Derien & Campbell. [54] Associated with the cedar lumbering, Dennisville boasted several talented shipwrights. Two important shipyards were the Leaming Yards and the Isaac Gandy and Jesse Diverty shipbuilding operation. Ships were built lengthwise along the narrow creek and launched sideways into the water, moving farther out with each high tide. [55]

Several prominent captains acquired great wealth from shipping lumber and produce. These men, in turn, built elegant frame homes that date to the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Today, sixty-nine sites are included in the Dennisville Historic District; fifty-eight are historically significant. In addition to its houses, Dennisville is known for being the first Cape May County town to have a post office, established in 1802. [56]

Goshen

One of the oldest towns in the county, Goshen was first settled in 1693: Aaron Leaming (the first of nine men of that name) raised cattle here. A cluster of houses appeared in 1710, and it became a stagecoach stop on the Philadelphia-Cape May route. Like Dennisville, Goshen's industrial history centered around lumbering and ship building. Some of the shipyards were along Goshen Creek, where the vessels were, again, launched sideways because of the narrow channel. The town was fifth in the county to receive a post office. [57] Today, Goshen consists of several houses, a post office, two churches, a school, municipal building, and filling station, primarily along Route 47/Delsea Drive.

Nummytown

Named after King Nummy, a Lenape Indian chief, the area that includes Nummytown, Dias Creek, Cape May Court House, Fishing Creek, Mayville, Cold Spring, Wildwood, and Tuckahoe were Indian campgrounds. These villages were the destination of Indians making their summer migration to the shore to collect seafood and wampum. The local Indian population never exceeded 500, and thus did not threaten white settlers. By 1735 most of the Indians from here had migrated north. [58] Today, much of what was Nummytown has been developed into campgrounds, shopping areas, and residential neighborhoods.

Rio Grande/Hildreth

Rio Grande was originally the intersection of the earliest roads: the King's Highway (Shore Road) from Tuckahoe to Cold Spring, and the road from Dennisville and Goshen (Delsea Drive). The town developed gradually throughout the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, first as a stagecoach stop and later as the last railroad stop for passengers bound for the beach resorts; vacationers traveled from Rio Grande to the shore via stagecoach. [59]

Unlike Goshen and Dennisville, the industrial innovations aided Rio Grande's development. While the other two declined in importance because they could not access the railroad, Rio Grande embraced rail and automobile traffic. In the early twentieth century, two industries were here: Rio Grande Canning Company and J.S. Brown carriage factory. [60] Today Rio Grande, too, like its neighbor Nummeytown, is recognized by its strip shopping malls, small businesses, and residential development. Few remnants of its early history remain.

Town Bank/Portsmouth/New England Village

Town Bank was originally settled by New England whalers who came here on a seasonal basis. As time passed, however, more of the whalers stayed year-round and eventually moved inland. In 1692 the town was made the first county seat, though it diminished in size and importance as whaling dwindled and the Delaware Bay reclaimed coastal lands. The site of the original Town Bank is underwater; the current Town Bank is an unrelated residential community. [61]

Cape May, Salem, and Cumberland counties are peppered with small, rural towns that in general retain a good portion of historically significance buildings. The most exemplary are Dennisville, Greenwich, and Mauricetown where there has been little modern intrusion. Despite some contemporary alterations and new construction, the historic cores of Salem and Bridgeton area are also characterized by its historic appearance. Towns that do not have designated historic districts should be considered for further investigation. Among the fast-food restaurants and modern offices in Millville and Pennsville a variety of historic structures are extant that should be studied for their historic value. Small towns such as Cedarville, Newport, Dividing Creek, Fairton, Quinton's Bridge, and Hancock's Bridge also feature a number of historic resources that warrant study and consideration for historic designation.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

new-jersey/historic-themes-resources/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 14-Mar-2005