|

National Park Service

Historic Themes and Resources within the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail Route Southern New Jersey and the Delaware Bay: Cape May, Cumberland, and Salem Counties |

|

CHAPTER 3:

MARITIME ACTIVITIES

The Delaware Bay and the rivers of South Jersey have provided essential sustenance to most of the region since occupation by the Lenni Lenape Indians who traveled to the coast to fish and gather shellfish. Peter Watson wrote from Perth Amboy in 1684 that, "the Indians in the summer, along with their wives come down the Rivers, in the Cannoas, which they make themselves of a piece of a great tree, like a little Boat, and there they Fish and Take Oysters." [1] All parts of the oyster and clam were utilized: Wampum, made out of the shells, was a common currency among the Indians.

Whaling

The earliest recorded maritime-related industry was undertaken by the first settlers in Cape May Town, or Town Bank—whalers from New England who initially migrated south during the summer season. By the 1670s they had established a permanent residence there. The whalers hunted freely off the Delaware Bay coast, but Indians competed with them for the great mammals that were beached on the shore. The rivalry did not inhibit the whalers' prosperity, however, and many acquired land and large inventories of goods through the sale of whale byproducts. In 1695, for instance, Caesar Hoskins owned 150 acres, Samuel Matthews 175 acres, Thomas Hand 400 acres, and Henry Stites 200 acres. Upon Stites' death his property, valued at £174-10 shillings, included horses, cattle, sheep, swine, a whale and tackling. Other prominent Cape May whalers included Caleb Carmen, Christopher Leaming, and Lewis Cresse. [2]

Whaling businesses such as Humphrey Hughes' Hughes and Company were established as early as 1666. Hughes, along with Nicholas Stevens of Boston and John Cooper of Southampton, were given the right to claim all beached whales. Thirty years later, a group of London businessmen established the West New Jersey Society and bought 577,000 acres of land in the area, though its efforts toward exporting whale products to England failed. [3] Otherwise, whale hunting was a community effort. The animals were spotted from watch towers erected in the coastal towns. Upon death boat, a sighting, six crewmen—a harpooner, boat-steerer, and four oarsmen—ran to the boats, which were usually built locally. [4]

Colonial newspapers regularly reported on the whalers' success, as did the Boston News Letter of 24 March 1718, when it reported that six whales were killed off Cape May and twelve off Egg Harbor. Economy dictated that nearly all parts of the whale be used to some end: Oil and bone was shipped to other colonies and Europe. Sperm oil, in particular, produced a clean and bright light, so it was used in domestic, street, and lighthouse fixtures; it was also an ingredient in soap, cosmetics, and lubricants. Bone was used in the manufacture of canes, whips, helmet frames, broom whistles, and as spines for corsets, umbrellas, and parasols. Bones and tissues were ground up and applied as fertilizer. [5]

By 1700, the indiscriminate killing of cow whales caused the number of this species to decrease markedly. As a result, whalers turned to larger boats to take them farther off the coast for the hunt; with this shift, some settlers opted for the less-arduous business of cattle raising, farming, and trapping. Whaling, however, was undertaken well into the late 1700s. The last whaling transaction recorded occurred in 1775 and pertained to the leasing of Seven Mile Beach by Aaron Leaming to whalemen for thirty days. [6] Today, the Cape May County Museum displays whaling gear as a reminder of the once-thriving local industry.

Trade

While whalers prospered in Cape May during the seventeenth century, residents of Salem and Cumberland counties were pursuing shipbuilding and trade. The first ports in South Jersey were Salem and Greenwich. Salem became an official port of entry in 1682, Greenwich in 1687. As such, these towns contained custom houses where British taxes were collected from arriving ships. A port of delivery served as a ship's destination port as opposed to any other port where the ship might receive provisions, orders, or refuge from storms. [7] The locations were ideal. "Both were located [away] from the tidal marshes on fast ground bordering a major stream: Salem on the east bank of Salem Creek and Greenwich on the west bank of the Cohanzy." [8] They remained important centers of trade until the Revolutionary War, and Salem was fully operational when Philadelphia was still a foundling colonial hub. The founder of the towns, John Fenwick, foresaw their potential, and devised wide streets to accommodate the traffic: Salem's Wharf Street, or Salem Street, was 90' wide, and Greenwich's Ye Greate Street was 100' across. Both were lined with houses and shops that terminated at water's edge amid a cluster of docks. [9]

The items exported from here were diverse. With agriculture the biggest inland industry, they included wheat and corn, as well as beef, tallow, and animal pelts. [10] The woodlands supported the production of shingles, boards, staves, hoops, and raw timber. Wood products, especially, were shipped primarily to other colonies—most frequently Delaware, Pennsylvania, New York, and the West Indies; otherwise, it was used locally to build and repair ships, wharfs, and warehouses.

Philadelphia received a large quantity of the products exported from South Jersey. Agricultural items went to the southern colonies until the late eighteenth century, when agricultural production there increased. New England and the West Indies received primarily grains and agricultural supplies, and some wood products. In turn, Greenwich and Salem merchants imported refined products and amenities such as rum, furniture, iron, wine, whale oil, codfish, sugar, molasses and salt. When the political situation changed, fewer goods were traded with England; then colonists in South Jersey who wanted European goods looked to Philadelphia. [11] The Revolutionary War marked the decline of the importance of Salem and Greenwich as trading centers, though it did not mean the end of active port towns in the region.

During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress considered Cape May of strategic importance as the entrance to the Delaware Bay. To ensure protection of river and bay, the Cape May Committee was established to inform the Congress about enemy movement. The only battle fought in Cape May County was on June 1776 at Turtle Gut Inlet, where the brigantine NANCY ran aground while carrying arms and munitions for the Continental Army. The British tried to intercept, fired upon her, and the crew abandoned the ship for fear of explosion. As they retreated, a sailor lowered the flag and took it with him. The British captain interpreted this move as a surrender, and he boarded her just as the ship exploded, killing fifty of his soldiers. Cape May County encountered more British activities than Salem and Cumberland counties during the War of 1812. Again, the British realized the important location of Cape May and its farmland, and repeatedly raided coastal farms for food and fresh water. In one instance the colonists sabotaged the enemy's supply by digging trenches from the bay to the freshwater Lily Lake. [12]

In 1789, Congress established districts for the collection of duties, one of which encompassed the area on the Delaware River from Camden to Cape May. Bridgeton was established as the port of entry, which served as a point for ships to load and unload under the supervision of customs regulators, and Salem and Port Elizabeth as ports of delivery. Like Salem, Bridgeton and Port Elizabeth were chosen for their locations at the head of navigable rivers—Bridgeton on the Cohansey and Port Elizabeth on the Maurice and Manumuskin Creek. Less-important river settlements on or between smaller streams included Hancock's Bridge, Thompson's Bridge, Alloway Creek, Millville, Port Norris, and Dennisville.

Ship Building

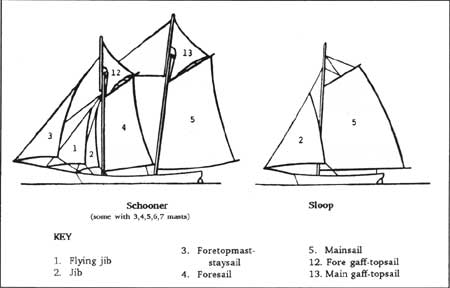

Many of the ships that were built and based in the area were sloops or schooners (Fig. 24), similar to the vessels that sailed from Salem and Greenwich prior to the war. As trade ships they carried lumber, hoops, coal, coal oil, vitriol, salt cake, brick, stone, fertilizers, railroad ties, tobacco, sugar, farm products, furs and ice as far north as Newfoundland and as far south as South America. [13]

|

| Figure 24. Diagram of schooner and sloop type vessels, identifying sails and rigging. Guidelines for Recording Historic Ships. |

Though the earliest vessel for general transportation was the dugout canoe used by the Indians, most area towns—Bridgeton, Cedarville, Dennisville, Dividing Creek, Dorchester, Fairton, Goshen, Greenwich, Leesburg, Mauricetown, Millville, Newport, Port Elizabeth, and Port Norris—were historically home to shipwrights and shipyards. Here were built shallops, sloops, and schooners for oystermen and fishermen in the region, as well as for use by traders based in Philadelphia and New York. New York and Philadelphia businessmen invested in Jersey-built ships and then registered them in those cities. [14]

|

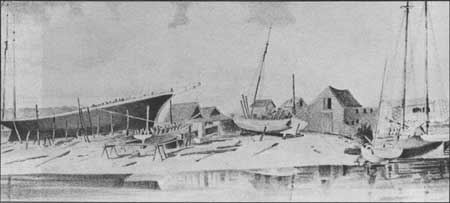

| Figure 25. Shipyard of F.L. Mulford, Millville. Atlas, 1876. |

Shallops and sloops were common craft around the Delaware Bay and its rivers in the early colonial period, popularly used for trade. Use of these two types of ships—for oystering, fishing and trading—declined after the versatile schooner was introduced to the colonies in 1760. Colonial shipwrights built the first schooners based on early eighteenth-century English and European examples, with new hull designs and changes in the rig instituted later to render the vessel easier to handle and better suited for a small crew. These first schooners were used primarily for commerce. In addition, each region developed its own variations. "Local hull types were designed to meet prevailing conditions such as tide, depth of water, weather, and wind, as well as the demands of a particular service such as fishing or freighting." [15] In the 1730s one design, the "Virginia" model, appeared often and it influenced the designs of two classes of schooners. One, the large, speedy, seaworthy, and ocean-going schooners such as the "Baltimore Clipper" type class was prominent by the War of 1812. [16] The Virginia model also influenced the design of a smaller schooner-rigged vessel, the pilot boat. Between 1830-60 it was developed as an oyster boat and became known as a "Bay Schooner"—referring to the Chesapeake Bay. Once the local oyster industry escalated, the Bay Schooner was modified to adapt to the Delaware's strong tides and shallow waters. By the 1920s, Delaware Bay schooners had taken on their own unique characteristics. Increased length of the hull lines, a freeboard with a long sweeping sheerline, and smaller heart-shaped sterns with elliptical tops characterized New Jersey schooners. [17]

The growth of the oyster industry in particular led more local shipwrights to build schooners; sloops also were "dismantled and refitted as schooners with fore and aft rigs." [18] Between 1870 and 1935, 153 wood vessels were produced in Bridgeton, 100 in Dorchester, 71 in Leesburg, 61 in Mauricetown, 55 in Millville (Fig. 25), 38 in Greenwich, 32 in Port Norris, 17 in Newport, 16 in Cedarville, three in Fairton, and two in Port Elizabeth. [19] The Del Bay Shipyard, now owned and operated by WHIBCO Inc., is an example of how other shipyard facilities might have appeared (Figs. 26-27). The site consists of several sets of long, three-story rectangular buildings. The interiors of these buildings are virtually vacant and provide room for the construction of schooners and other vessels, though written and graphic evidence suggest most were built outside. During World War II, the shipyard constructed mine sweepers for the American government. The Del Bay Shipyard operated well into the latter part of the twentieth century.

|

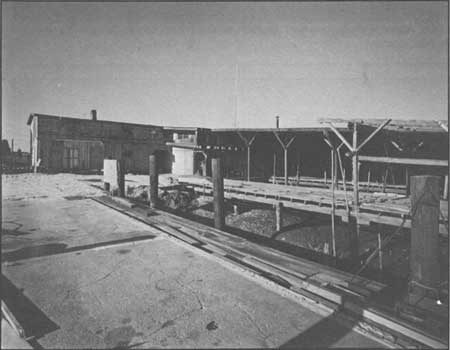

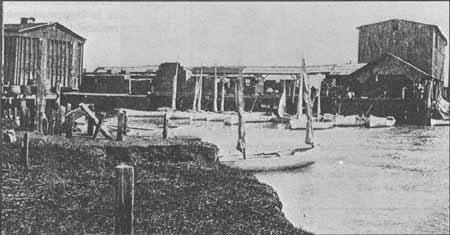

| Figure 26. Del Bay Shipyard, located in Leesburg, repaired and built schooners as well as other vessells, including World War II mine sweepers. |

|

| Figure 27. Today WHIBCO Incl., a local sand-mining company, uses the Del Bay Shipyard facilities as its headquarters. |

The number of boats built in Cumberland during the same period ranked it as the second-largest boat building county in New Jersey (after Camden County). Cape May County ranked third: from 1870-99, shipwrights were responsible for forty four vessels from shipyards in Dennisville, Goshen, Tuckahoe, and Marshallville. When yards in the last two towns shut down in 1883, Dennisville makers compensated, and from 1871-91 produced twenty-six three masted vessels. A decline in Cape May County ship production occurred in the 1880-90s due to a demand for larger ships than what could be built locally, coupled with a depleting local lumber supply. [20]

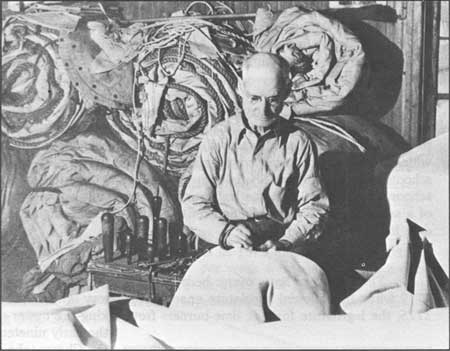

As the oyster industry modernized, so did the New Jersey-style schooners. Wind power dredges gave way to motors. In turn, the time spent working and living on the boat shrank to daylight hours. The absence of sails (Fig. 28) also invited the addition of pilot houses, which shifted the captain's command center from below deck to above. Today several schooners in the Bivalve/Shellpile area have been converted to power engines. Most existing schooners pre-date 1930, the last year they were built in the area. The oldest extant example of a schooner built with sails and refitted with a power engine is the CASHIER, believed to date to 1849 (Fig. 29).

|

| Figure 28. Sailmaker Ed Cobb working in the sail loft of a building that is extant in Bivalve. Rutgers Collection, early 20th century. |

|

| Figure 29. The CASHIER (ca. 1849), moored in Commercial Township, is believed to be the oldest commercial fishing boat in use in this country. Leach. |

Oystering

The Delaware Bay's oyster beds were recognized as an important resource as early as 1719 when the colonial legislature enacted regulatory laws to prevent their pillaging. In 1775, the legislature forbade lime-burners from taking the oyster shells for making lime. By the early nineteenth century, oystermen in the Chesapeake and Delaware bays adopted the use of wood dredges with iron teeth and a rope mesh bag, instead of the traditional tongs or rakes. Dredging generated a larger oyster harvest and was improved after the Civil War when the frame and mesh bag were made out of iron. [21]

|

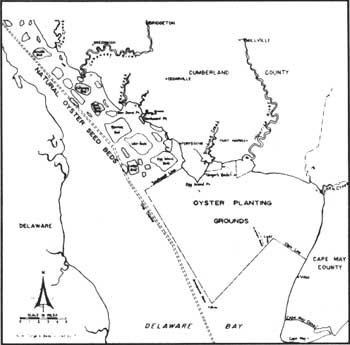

| Figure 30. Oyster growing areas in the Delaware River-Bay, showing seed beds and planting grounds. Undersail. |

It was not until the late 1800s, however, that the Delaware Bay oystering industry boomed, although the procedure for gathering and processing the oysters changed very little during the nineteenth century. The oysters were dredged up, brought to the mouths of creeks and rivers, and placed in large bins atop the mud flats where the tide washed through them. Once cleaned, they were loaded on to boats or wagons en route to Philadelphia. [22] Efforts were undertaken to escalate production and profit, but one factor working against the oystermen was the demand for shells to be ground into lime. This depleted the shell supply needed to host (provide a shell surrogate) seed oysters, and caused state officials in 1846 to close the oyster beds during the summer. This led to a fortuitous discovery after some oystermen gathered a load of oysters and took them to Philadelphia and New York markets—only to find that they were overstocked. The men returned home and dumped the bivalves nearby in deep water. In the fall they discovered that the oysters had fattened, and hence the oystermen realized the potential of moving the small ones from shallow beds and relocating them to the deeper and saltier waters of the Delaware Bay. Transplanting oysters thereafter became a widespread practice that boosted profitability but continued to deplete the natural beds. Moreover, many seed oysters were shipped to New England. As the supply of these shellfish continued to decline, New Jersey oystermen had to go as far as Long Island Sound to acquire seed oysters for the following harvest. [23]

The arrival of the railroad to the Maurice River area in 1876 enhanced the oyster industry. The first year an average of ten cars of oysters per week were shipped out; a decade later—about the time protective laws were being enacted—an average of ninety cars per week departed Bivalve. At the same time, more than 300 dredgeboats and 3,000 men were involved with Delaware Bay oystering (Fig. 30) [24]

In an effort to preserve the limited supply of seedlings in the area, the New Jersey legislature initiated a series of protective laws. In 1893, the state was divided into seven districts "with a commission of fourteen members to promote the propagation and growth of seed oysters and to protect the natural seed grounds." The legislature empowered the planters' association of Maurice River Cove to make rules governing the industry, to employ guards, and to assess fees. In 1899 the state passed yet another bill to enhance the protective stances of the first two bills. Fifteen years later, New Jersey created the Board of Shell Fisheries to further ensure the longevity of the Delaware Bay oyster harvest, which by 1917 had evolved into a $10 million a year industry. [25]

|

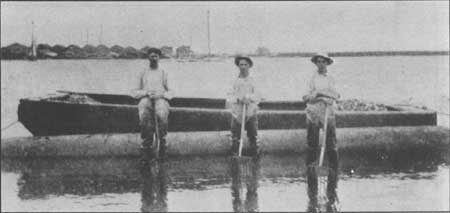

| Figure 31. Taking up oysters at Bivalve shwoing the iron rakes, flat oyster boat, and processing houses of Bivalve in the background. New Jersey: Life early 20th century. |

|

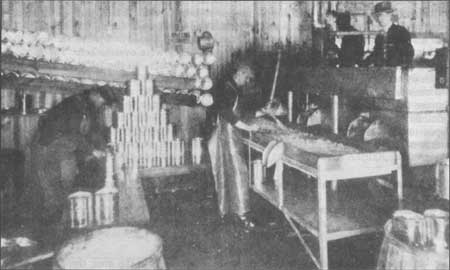

| Figure 32. Canning raw oysters at Port Norris. New Jersey Life, early 20th century. |

|

| Figure 33. Packing oysters in baskets at Port Norris. Wettstein, pre-1904. |

|

| Figure 34. Interior of shucking house showing workers in their cubicles and ketles filled with shucked oysters. Undersail, ca. early 20th century. |

|

| Figure 35. Shucking house on the Maurice River where oysters are opened and prepared for shipping. Undersail, 1920s. |

The move from sail to motor power in the early twentieth century disrupted the network that united the oystering community. The crew, no longer needed to control the sails, instead culled oysters, which improved efficiency. The culling process—separating the good oysters from bad and other trash—was also mechanized. During the 1930s schooner production fell, and eventually shipwrights only repaired the old boats. Motors made sail-makers and riggers obsolete. By the end of the decade, the only surviving auxiliary industries were dredgemaking, some smithing, and the furnishing of machine parts. [26]

In 1950 oystermen suffered an even greater setback, unrelated to industrial progress. The oysters grew susceptible to the MSX virus, a parasitic attack that weakens or kills an oyster, which has virtually ended all oystering on the Delaware Bay. Today, only thirty boats work the bay compared to the 500 active oyster vessels at the peak of the industry. In an effort to combat the MSX menace, scientists at the Rutgers Experimental Station in Bivalve, at one time the major oyster port on the bay, are working to develop a stock of virus-resistant oysters.

Today, Bivalve contains the architectural remnants of its once-flourishing oyster industry that historically included the towns of Port Norris and Shellpile; much workers' housing stock has been demolished. The processing houses (Fig. 36) are extant here, though they have been somewhat modified since 1904 when erected by the Jersey Central Railroad. The plain frame buildings are set at the shoreline, with finger-like docks extending into the shallow waters sheltered by a shed roof; vessels entered this space and originally dumped their shellfish cargo for a natural rinsing. The enclosed buildings housed the workers and ancillary industries such as sailmaking.

|

| Figure 36. Oyster processing at Bivalve (ca. 1904). Workers bunked upstairs, processing occurred below; the N.J. State Police is the current tenant. |

Caviar

During the 1860s when oystering was on the verge of its boom, another maritime industry had already developed at the mouth of Stow Creek, in the fishing village and namesake of Caviar—now called Bayside. During the fishing season, approximately 400 fishermen lived in the nearby cabins and houseboats, with access only to a store, post office, and train station. The last was critical, because many fish were transported by train to New York City, and sturgeon fishermen at Cape May Point used Caviar's station to off load their catch (Fig. 37). Sturgeon meat and the eggs for caviar were sold to boats that waited off shore, which then delivered them to steamboats en route to Philadelphia. [27]

|

| Figure 37. Sturgeon docks at Caviar/Bayside. Rutgers Collection, ca. 1930. |

One prominent sturgeon fishermen was Harry A. Dalbow who, in 1891, formed a partnership with Joseph H. Dalbow. The ten-year association started with two sailboats and nets, and grew to encompass a fleet of about twenty large gasoline-powered boats. The Dalbows' work extended longer than the summer season in Caviar; to North Carolina and South Carolina in the winter, and in the fall to Maine and Canada. Fishermen commonly migrated each season, despite efforts in some jurisdictions to outlaw non-resident fishing. In addition to the sturgeon fishing, Dalbow undertook a canning venture. With the help of the American Can Company in Penns Grove (just north of Deepwater) he started packing caviar in small, vacuum-sealed glass jars. Other companies canned its caviar in kegs made in Russia, but Dalbow's process was so successful that he went there to help found canneries like his own in Astrakhan and Baku. [28]

By 1925, factory and sewage pollution coupled with over fishing caused the sturgeon and caviar industry on the Delaware to diminish. In 1904, the Sturgeon Fishermen's Protective Association discussed passage of a law forbidding the landing of any sturgeon under 4', since fish this size are of little value as a source of caviar. State laws were eventually passed but not before most of the sturgeon in the Delaware Bay had disappeared. [29]

In the Penns Grove area four shipyards supplied sturgeon fishermen with boats at various times. In addition, the men were dependent upon local men, women, and children to make the necessary 12" mesh nets; in 1890, machine-knit 11-13" nets replaced handmade ones (Fig. 38). [30]

|

| Figure 38. Fisherman drying nets. Rutgers Collection, early 20th century. |

Menhaden

Another maritime industry to emerge in the last quarter of the nineteenth century was menhaden fishing. Menhaden, or bunker fish, stays in marshy areas and moves south in the fall. Not a delicacy for human consumption, the fish caught in the bay at the turn of the century were taken by steamboat to a local factory between Leesburg and Heislerville where it was processed. [31] Although the facility is gone, Menhaden Road recalls the place where the fish were "cooked with steam, the fish oil pressed out and the remains dried and ground into fish meal for animal feed and fertilizer." [32] The oil was used in the manufacture of paints, inks, soaps, and lubricants.

Crabbing

In recent years crabbing has become a major industry on the bay, as well as a weekend recreation. Blue crabs are found throughout the tidal waters of New Jersey, and although they are a critical food group to watermen today, the enterprise of crabbing has fluctuated drastically since the end of the nineteenth century. In the 1880s, for instance, approximately 1.5 million pounds of crabs were captured, while in 1890 the harvest was less than 100,000 pounds. [33]

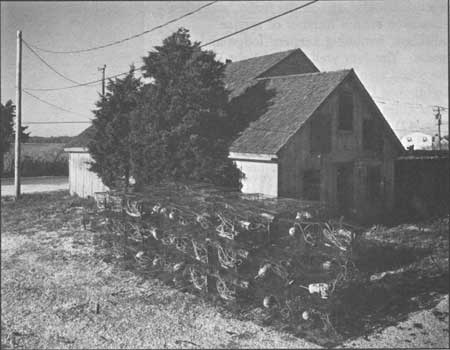

The volume of crabs did not peak akin to the 1880s level until 1940, when almost 5 million pounds were caught. The increase is attributed to the replacement of baited trot lines with the self trapping crab pot (Fig. 39). Used mostly during the summer harvest when crabs actively feed, trot lines—with 100 or more baits tied at intervals—could stretch as long as 1,000'. In the winter fishermen dragged dredges behind their boats, allowing the teeth of the dredges to scrape out the dormant crabs; dredges are still used during the winter harvest. Today, the crabbing industry continues to flourish, as does the use of the crab pots, such that in 1985 an estimated 1.6 million pounds of crabs were caught. In addition, a private company in Shellpile deals in aquaculture, flash freezing soft-shelled crabs for export to Japan. [34]

|

| Figure 39. Crabbing pots outside a Bivalve storage building. |

Lights/Lighthouses

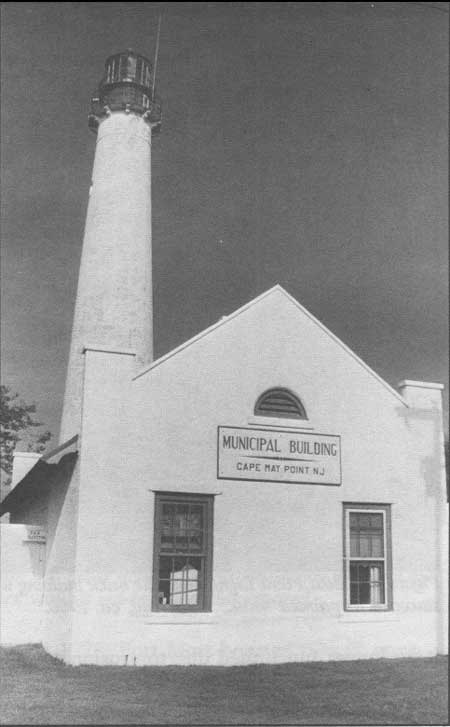

To ensure the safety of the different vessels that traversed South Jersey coastal waters, a number of lighthouses, towers, and beacons were erected. Unlike some transportation-related structures, these nineteenth-century structures have not been replaced by a modern equivalent mechanism—though the lights themselves have all been automated. These utilitarian structures, erected on land and in the water, are often associated with a number of service buildings, including keepers' lodge and oil house. The four well-known light houses in the study area are Finn's Point Rear Range Lighthouse (Fort Mott Light), East Point Light (Figs. 40-41), ShipJohn Lighthouse (Fig. 42), and Cape May Point Light (Fig. 43). [35]

In 1837 the federal government bought land at Finn's Point to erect a battery that would help Pea Patch Islanders defend Philadelphia and the river in the event of attack. At first slated as a temporary facility, it was made permanent in 1870. By 1878, Fort Mott boasted two 8" guns, and the battery was strengthened ten years later during the Spanish American War. The fort was named after General Gersham Mott, commander of New Jersey volunteers in the Civil War. [36] During World War I, Fort Mott also safeguarded Carney's Point where E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co. manufactured gun cotton used in mines, torpedoes, and propellants. The fort closed after World War I. [37] Finn's Point National Cemetery, near Fort Mott, was used during the Civil War as the burial site of Confederate soldiers who succumbed to cholera and other diseases while imprisoned on Pea Patch Island. In 1875 the government designated it a national cemetery.

|

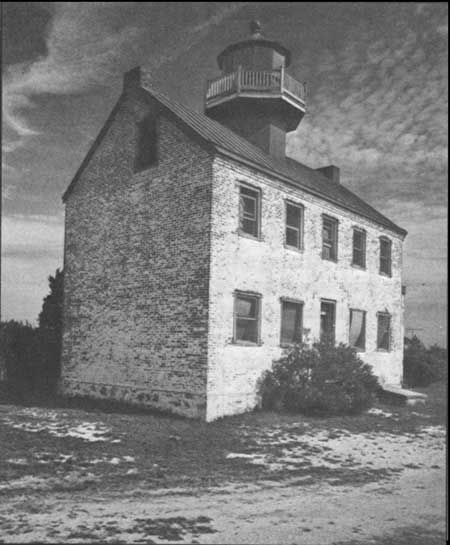

| Figure 40. East Point Light (1848) today is empty but intact, with its red-brick exterior exposed. |

|

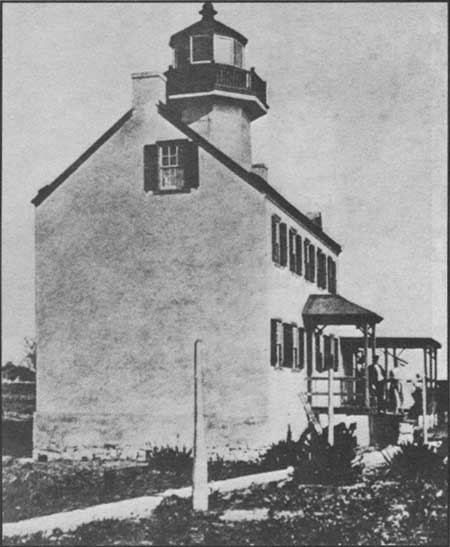

| Figure 41. East Point Light when the brick stuccoed or painted white. Undersail, ca. 1900. |

|

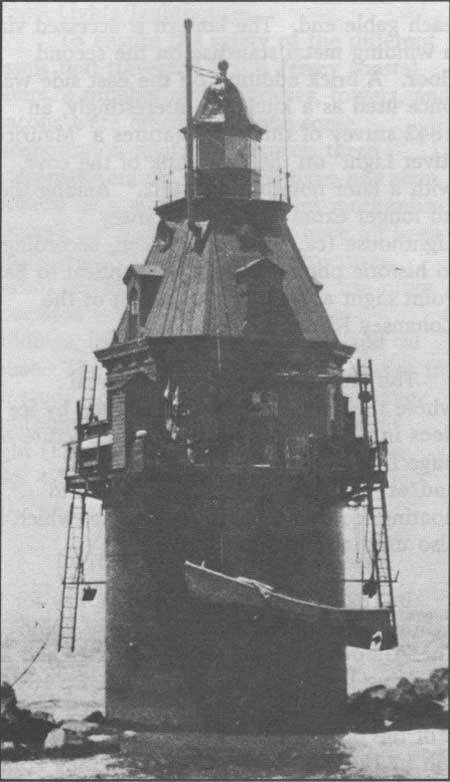

| Figure 42. ShipJohn Light (pre-1876) is a Victorian caisson-type light in the Cohansey River. Undersail. |

|

| Figure 43. Cape May Point Light (1859), consists of a free-standing tower and keepers' dwellings. Leach. |

East Point Lighthouse (1848), built to guard the eastern shore of the Maurice River Cove, represents the only local example of a Cape Cod-style form—simply a lantern atop a gable-roof structure that resembles the regionally indigenous I-house. The low height was typical of mid nineteenth-century lights in a geographically flat area; structures thereafter reached 150-170'. It is brick, three bays wide, and one room deep with interior chimneys on each gable end. The lantern is accessed via a winding metal staircase on the second floor. A brick addition on the east side was once used as a kitchen. Interestingly, an 1842 survey of this area features a "Maurice River Light" on the east bank of the cove, with a later notation of "1882." Among the no longer extant sites is Cohansey Lighthouse (ca./pre-1842) which, according to historic photographs, was identical to East Point Light and sat at the mouth of the Cohansey River.

The ShipJohn Light is on a shoal where the ship JOHN was destroyed by ice floes in 1797. This caisson-type structure—a huge iron tube filled with rocks, sand, and/or concrete—was less vulnerable to floating ice than the screwpile type, which is also used at non-landed sites.

In 1821 Congress approved money for a lighthouse to be built on Cape May Point. The 70' tower erected two years later had a revolving light with fifteen lamps. By 1847 it no longer functioned due to erosion of the shore, and a second structure was erected on Great Island bluff, one-third of a mile from the site of the original; it, too, was lost to erosion. The third and present Cape May Point light was built in 1859 at what is now Cape May Point State Park. The light atop the free-standing 170' tower has been automated, and the site includes two modest gable-roofed keeper's dwellings that have been restored. [38]

Finn's Point Rear Range Lighthouse (1877) is in what today is the Supawna Meadows National Wildlife Refuge near Fort Mott north of Salem. This light was erected to guide naval traffic around the shoals and islands of the Delaware River. Completed in 1877 by the Kellogg Bridge Company of Buffalo, New York, the tower measures 100' from base to focal plane. Constructed of wrought rather than cast iron, the skeletal tower rests on a freestanding masonry base, a type of construction popular from the 1860s. The tower platform is reached by a spiral, cast-iron stair. The iron cylinder is entered through a "handsome classical galvanized iron doorway, which has a pedimented aedicule motif, molded capitals and paneled pilasters." [39] The light was automated in 1939 and discontinued in 1951. [40]

Some of South Jersey's light structures are lost. Another lighthouse existed at Egg Island, just north of the southern terminus of the point. Two "signals" are indicated to have existed as late as 1842-43: West Creek signal, on the west bank of that waterway, and Goshen Signal, located between Goshen and Withs creeks. [41]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

new-jersey/historic-themes-resources/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 14-Mar-2005