|

National Park Service

Historic Themes and Resources within the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail Route Southern New Jersey and the Delaware Bay: Cape May, Cumberland, and Salem Counties |

|

CHAPTER 4:

AGRICULTURE

Agriculture has been a way of life in South Jersey since the eighteenth century, and all three counties have remained devoted to some agricultural pursuit into the twentieth century. The first farmers here were the Lenni Lenape Indians who cleared land by burning underbrush and girdling trees. Among the plants they domesticated and cultivated were several varieties of corn—flint corn, popcorn, and sweet corn—kidney and lima beans, pumpkin, Jerusalem artichoke, sunflower, and tobacco. They also harvested wild rice and gathered chestnuts, walnuts, hazelnuts, hickories, and butternuts. Indians taught the first whites about such indigenous wild foods, and they are credited with providing the newcomers with many of today's popular commercial products: corn, blueberries, strawberries, cranberries, and sugar maples. [1]

The sequence of white settlement also introduced familiar farming practices from European homelands and other colonies. The Dutch, for instance, introduced cabbage, lettuce, carrots, radishes, parsnips, beets, spinach and onions, as well as a variety of flowers and fruit trees. In the late eighteenth century, the Irish brought with them white potatoes, and visitors to the Caribbean returned with sweet potatoes. Livestock supplemented crops: sheep, cattle, horses, pigs, and chickens. All but the easily victimized sheep roamed the woods and open fields freely; to protect the crops, however, colonial law required that fields be enclosed by worm, or Virginia, fences made of split rails laid in a zigzag pattern. [2]

Farms then, as today, were dominated by the dwelling house, surrounded by a complex of service structures: barns, sheds, spring house, and perhaps a windmill. There are few examples of seventeenth-century dwellings extant in rural South Jersey, though the greater number of resources were erected during the ensuing two centuries. Eighteenth-century farm housing is stratified by location: Salem County and Greenwich contain Quaker and other brick Georgian forms, and exclusively those with patterned gable ends—as is discussed in Chapter 2 and Appendix I: Patterned Brick Work. In contrast, Cape May County's dwellings are generally frame with a smattering of brick Georgian forms found along the main roads; Cumberland County contains elements of both, though nineteenth-century Victorian construction rivals that of the previous century. Two vernacular dwelling types are found throughout the study area: one-cell, two-story stack houses, usually with a lateral shed, and migrant-worker blocks.

In Cumberland County there is one confirmed seventeenth- and a few eighteenth-century brick houses; of these, some are ornamented by only Flemish-bond coursing. This area is within the fifty-mile radius of Philadelphia influenced by early Quaker builders, and where brick was preferred, as opposed to the Mid-Atlantic, west of an imaginary Philadelphia-to-Princeton line, where stone was used more often. Here, the talents of a diverse group of carpenters and masons immigrating from different regions of England were scattered, resulting in, for instance, the diaper pattern in Salem's brick houses. [3]

Like patterned brick work, the two-thirds Georgian plan has been attributed to the Quakers, hence it is sometimes called the "Quaker-plan"; the appropriateness of this is debated among architectural historians, folklorists, and cultural geographers. [4] In South Jersey, many of the houses erected in Quaker settlements are two-thirds Georgian, however, with the characteristic side-hall, two-pile plan.

The old Salem houses . . . are typical examples of Quaker architecture. Two stories high, wide of front, with interior end chimneys, pent roof in front but not at the ends, the door occasionally hooded. . . . [5]

The abundance of wood was one factor to influence the choice of frame versus brick as a building material in the towns and countryside of Cape May and Cumberland counties. This is especially true for the low-lying bayside region of Cape May County examined in this study. Regardless of a structural difference, the majority of dwellings built here in the eighteenth century were stylistically Georgian. In Cape May County, many of these are found along Route 47 (which follows the historic thoroughfare from the point northwestward), and are either two-thirds Georgian or a full five-bay Georgian. These residences are formal and imposing, despite the relatively rural setting and historic farmhouse function. This may be explained in part because the soil in Cape May was poorer than that of its neighbors, so to prosper, the settlers of north Cape May County ventured well beyond the bounds of established towns such as Cape May Courthouse and Cold Spring. These towns were uncharacteristically inland, and thus inhabitants dependent upon shipbuilding or related industries had to gravitate either deeper into the interior and land routes, or closer to the water. Settlement patterns also reveal that planned towns were not prominent here and settlement was more random, compared to Salem and Cumberland counties. The first settlers, after all, were whale hunters who lived in temporary shacks for one annual season.

In South Dennis, on the west side of Route 47, there are two examples of the eighteenth-century house forms associated with an agricultural setting. The Thomas Ludlam House (1743, Fig. 44) is very plain block probably constructed in three phases, beginning with the leftmost, three-bay unit that terminates with the chimney. The portion on the right of the chimney, and the slightly smaller gable-roofed block, were undoubtedly added after the 1740s. As such the original space was a hall-and-parlor plan, the most common eighteenth-century arrangement. In keeping with the Cape May locale, the house is clad with weather-board and wood shingles. The first-story windows are six-over-six-light double-hung sash, while the upper loft windows are six-light single sash. This house was moved in 1972 from North Dennisville to its present site.

|

| Figure 44. Thomas Ludlam House (1743), originally a hall-and-parlor plan, has been enlarged with the addition of four bays and relocated below Dennisville. |

In contrast, the Christopher Ludlam House of thirty years later (1776, Fig. 45) is a more formal and spacious five-bay composition: a centrally placed door leads into a hall that is flanked by two rooms that were an embellishment of the hall-and-parlor function, and there are matching gable-end chimneys. Only one room deep, this is an I-house type that was popular throughout the Mid-Atlantic and South during this century. The first addition was made to the rear facade in 1833 to form a T or L plan, a common means of enlarging the property; the connecting garage erected in 1951 is sympathetic to the historic form.

|

| Figure 45. Christopher Ludlam House (1776), though plain, is an ordered, Georgian five-bay block with gable-end chimneys, center door, and rear additions. |

Two common farmhouse types erected from the late nineteenth through early twentieth centuries can be dated by their ornamental features, or lack of them: the older folk Victorian mode is an asymmetrical gable-and-wing composition, as compared with the boxier, three- or four-bay mass with a gable or cross-gable roof. Some are older Federal-style buildings that have been "modernized" through detailing such as eave brackets and spindlework porches, as well as, perhaps, central or paired gables, a steeply pitched roof, or pointed-arch windows.

Two examples of the latter model are the Burcham Farm House (Fig. 46) outside Millville, and the Howell Farm House, near Cedarville. Both are Century Farm Award winners—the farms having been owned and operated by the same family for more than 100 years. The Burcham House (ca. 1870), is made of brick fired on the property by the occupants' grandfather. Overlooking the Maurice River from a knoll, the house's subtle Victorian features are a high-pitched roof with a cross gable on the west/front facade, and L-shaped one-story porch that wraps around the front, supported by turned supports. Its siting on the ephemeral edge of the creek probably dictated the banked, three-and-one-half story mass—to gain as much safety and utilitarian space as possible at such a low sea level; minor additions have been made to the side and rear facades. Remaining outbuildings include a twentieth-century concrete-block barn, pig sty, windmill once used to generate electricity, and a small equipment shed made from the broken and poor-quality "brick backs" leftover from the manufacturing days. No evidence remains of the brick-making site.

|

| Figure 46. The Burcham Farm House (ca. 1870) is a vernacular Gothic Revival block, indicated by the center gable; the bricks were fired on the property. |

The Howell Farm House is similar to that of the Burchams, with its steep roof with a cross gable. Built prior to the 1870s, however, it was remodeled during the Victorian era to feature paired brackets along the cornice, and front and side porches highlighted by Queen Anne spindlework. The house is three bays wide and one room deep with a perpendicular rear addition that gives the block a T-shape. Internally, the original house is a side passage plan. Extant outbuildings on the property include badly deteriorated barns and sheds.

The more contemporary block is a squarish four bays wide and two piles deep with a shallow hipped or pyramidal roof. The Russell Glaspey House (ca. 1900) in Salem County and Charlie Loew House (ca. 1890), Cumberland County, are two examples. Both the front and back facades have later shed-roof porches. The Loew House has a gable roof with a boxed cornice adorned by dentils. Four bays wide and three rooms deep, it is arranged on a central-hall plan. Rectangular transom glazing and sidelights around the front door indicate Georgian or Colonial Revival styling. Extant outbuildings here include a twentieth-century dairy barn built of concrete block (replacing an earlier barn that burned) and a frame machine shed.

Farmhouses built here from the nineteenth century on are usually complemented by English barns and drive-in corncribs. These service buildings reflect South Jersey's early settlement by Quakers and other English colonists. The English barn has a rectangular-like frame with its door on the two- to three-bay long side rather than the gable end; foundations are brick or local sandstone. [6] The amount of interior space allowed for hand threshing. "Unthreshed grain was commonly stored in one side bay, and during the fall and winter threshed by hand using a flail on the central threshing floor. The threshed grain and straw were separately stored on the other side in the opposite bay, the grain in built-in bins." [7]

The English barn—basically a single-function structure—persists here as well as the Delmarva Peninsula, where agriculture is "strongly oriented to crop production and where major livestock are largely absent, even in areas of high agricultural productivity." Though dairy farming had been prevalent in Cumberland and Salem counties since the mid to late nineteenth century, the area's proximity to New York and Philadelphia encouraged truck farming and thus, "discouraged the erection of elaborate farm barns in the possible path of urban expansion." The absence of a basement was popular, too, because of the high water tables. [8] Farmers who maintained dairy cows often added concrete-block rooms to their traditional barns.

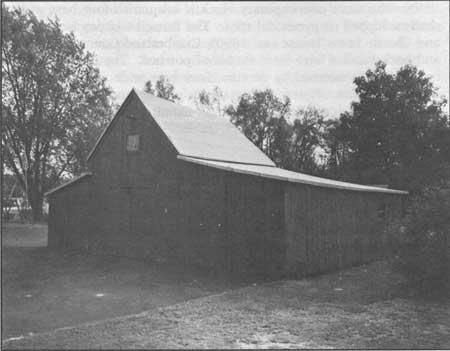

The drive-in corncrib with flanking sheds has been a component of the earliest farm complexes (Fig. 47). Today they continue to exist in areas where "farming never advanced beyond a rudimentary or subsistence stage." [9] In South Jersey, the corncrib was used to store corn or grain; lean-to shed additions to house animals or machinery. Most twentieth-century structures associated with the farming regions of Cape May, Cumberland, and Salem counties are minor outbuildings, as compared to the barns and corncribs of previous years.

|

| Figure 47. The drive-in corncrib form, here adapted for use as a garage, housed grain in the flanking compartments; the gable-end opening has been glazed. |

Market Days/Fairs

Seventeenth-century farmers sold crops and acquired new agricultural knowledge through fairs and written material. That fairs functioned as a glorified market day was an Old World tradition, and despite their commercial importance, social activities were also a major element. "With the scattered populations, fair day furnished the chance for a general gathering, and soon developed into a festive event." [10]

In 1681 the West Jersey Assembly established two annual fairs, to be held in Burlington and Salem, and a year later, Saturdays were designated the official market day in Burlington, and Tuesday in Salem. Also, semi-annual fairs in Salem were slated for May and October. In 1687 the Assembly established a fair at Greenwich as a semi-annual event held in April and October; unlike the Salem fair—which was aimed at farmers—the Greenwich event attracted traders from Philadelphia who sought pelts.

Despite efforts to keep the fairs orderly, some outsiders caused problems by selling liquor and encouraging horse racing. Some attempts were made by local governments to curtail the unruliness, as in 1698 when Salem officials banned the sale of liquor at fairs. Nevertheless, eventually the concept of fairs coinciding with market days was lost in an atmosphere of gambling and drinking. "All persons were at liberty to buy and sell all manner of lawful goods, wares and merchandise" at all fairs, where authorities could not arrest people for disorderly conduct two days before or afterward unless peace was threatened. [11]

By 1763, the chaos of the Salem fair increased so much that the New Jersey Assembly discontinued the privilege; two years later the town of Greenwich lost its right, also. Other towns in New Jersey, however, continued holding fairs until 1797 when the Assembly abolished fair privileges throughout the state due to abuse and neglect. With the cancellation of fairs in New Jersey, agriculturalists turned to societies, almanacs, newspapers and periodicals as a way to obtain the most up-to-date information on farming and husbandry practices. By the second decade of the nineteenth century, agricultural societies participated in the re-establishment of county fairs. In 1826, Robert Gibbon Johnson, a prominent Salem County farmer and member of the Pennsylvania and Salem County Agricultural Societies, promoted the reorganization of the Salem County fair. [12] In 1841, the New Jersey Agricultural Society sponsored a fair in New Brunswick. Among the events was a plowing match and a livestock sale. Later fairs had similar events in addition to horse racing, agricultural and household exhibits, and music. [13]

The Cumberland County Agricultural Society, organized in 1823, also hosted two-day fairs that were held on Vine Street in Bridgeton. Many of their events were akin to those sponsored by the Salem and New Jersey agricultural societies. One practical tradition that took place prior to opening day was the construction of a wood fence around the fairgrounds; afterward, the barrier was dismantled and sold as lumber. [14]

Societies

In the eighteenth century Benjamin Franklin, William Temple Franklin, Colonel George Morgan, and William Coxe, among others, promoted agriculture through membership in societies and the support of almanacs, newspapers, and journals. One prominent example was the Philadelphia Society for the Promotion of Agriculture. Founded in 1785, its members sought to establish an experimental farm that went unrealized because of a lack of funds. Prior to the organization of the Philadelphia Society, the New Jersey Society for Promoting Agriculture, Commerce, and Arts advertised for members in the New Jersey Gazette in August 1781. The notice was signed by Samuel Whitham Stockton, secretary. [15]

Both the Salem and the Cumberland county agricultural societies were founded ca. 1800. These societies, especially the one in Salem, boasted prominent members who were continually experimenting with ways to improve the crops and farming techniques in the area. Robert Gibbon Johnson, a member of the Salem Society, recognized that the land was exhausted from overfarming—and business was depressed as a result. The New Jersey legislature appointed him to oversee Salem County's agricultural-relief loan office. In an effort to restore farmers' faith, he stressed the use of calcium-rich marl to replenish the soil. According to popular legend, Johnson also proved that the tomato was not poisonous and, more important, that South Jersey's sandy soil was an excellent location to grow them. [16]

A modern equivalent of societies might be considered grange organizations, where topical political issues relating to agricultural industry also gave way to social and community gatherings. In South Jersey, grange buildings (Fig. 48) closely resemble one-story schools and community centers, as plain frame gable-roof structures painted white.

|

| Figure 48. Grange, No. 43 (1904), like other rural, municipal and school buildings, is an unadorned rectangular frame block painted white. |

Periodicals

Farmers relied on almanacs for their agricultural methodology as early as 1776. These less-than-scientific sources encouraged superstition by reinforcing such ideas as planting according to phases of the moon and home made medicines. One widely read almanac in the South Jersey area was Wood's Town and Country Almanac. "As a medium for the dissemination of useful information, [almanacs] can be considered the forerunners in this country of agricultural journals, of agricultural books and of college and experiment station bulletins." Newspapers provided well-founded information as well the folkloric beliefs dispelled by almanacs. By 1833, newspapers such as the Working Farmer had become so important that every county in New Jersey except Cape May had a weekly or daily paper. [17]

Other magazines published outside New Jersey but read locally included the American Farmer, Plough Boy and Rural Gentlemen. These included stories written by prominent farmers throughout the Eastern United States. In 1826 Robert Gibbon Johnson submitted to the American Farmer a series of articles relating to the most accurate method of draining meadows and marshes. Magazines devoted to New Jersey agriculture included the New Jersey Farmer, which was published in Bridgeton from 1869-74, the Bridgeton Monthly, first published in 1872, and the Vineland Rural issued around 1870.[18]

By the end of the nineteenth century, agricultural journals replaced almanacs and newspapers as the principle medium for disseminating farming facts. Journals, however, also played an important role in turning public sentiment toward favoring agricultural schools, colleges, and experimental stations such as Rutgers that were being established.

Education

During the middle of the nineteenth century, the establishment of an agronomy curriculum in local schools was officially addressed. In 1848, the Union Academy in Shiloh was the first school to teach it, under the leadership of E.P. Larkin who attempted unsuccessfully to get state funding. In 1860 the State Agricultural Society also promoted utilizing the State Normal School to train teachers in agronomy; they, in turn, instructed students with the latest methodology. Four years later, a school for higher education was formed in New Brunswick; Rutgers Agricultural College hence became the State College for the Benefit of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts. [19]

With Rutgers established as the state vehicle for agriculture training, its trustees purchased a nearby farm on which to conduct research. Once it was organized and self-sustaining, it became the headquarters for the experiment station where new farming techniques and cultivation problems were tested, and farmers were instructed. In 1880 the position of agricultural agent was established in each county. Since the 1880s, bulletins issued by Rutgers and its extension services have provided farmers with basic information concerning crops and farm animals.

Salt Hay

Salt hay (Spartina patens) is a sturdy, narrow-leaved cordgrass that grows in the tidal marshes that fringe the Delaware Bay and River where the saline content is high. The area between Salem and Cape May counties contains 79,282 acres of the marsh—a critical environment for humans and wildlife alike—which today is largely protected.

The first mention of its value came in 1685 when Thomas Budd proposed diking and draining portions of the salt marsh to support crops and cattle, as well as to reduce mosquito infestation. Heretofore these lands were considered a barren wilderness good for little more than pasture. Farmers let cattle graze on this public land, but by the late nineteenth century they were so numerous that branding was instituted to identify ownership. Salt hay was used as animal bedding and occasionally food in the late seventeenth century; though it lacked many nutrients, it was cheaper than traditional hay. Farmers improved the salt-hay meadows by ditching, and constructing dikes and sluice gates, which allowed the introduction of domesticated grasses, and by the end of the next century, clover was added. Once farmers recognized that salt-marsh meadows could be improved, the land was more desireable. [20]

With the increase in private ownership of the salt meadows, protective measures were established. The New Jersey State Board of Agriculture's list of meadows laws allowed owners to dam creeks and keep out the tides. By the 1780s these laws encouraged property owners to appoint committeemen who were charged with ensuring that banks, dams, floodgates, and sluices were in good working order. Later, meadows companies hired men to build earthen dikes and drainage ditches. [21]

The Hackensack and Passaic Company of North Jersey used its salt marsh to raise grains, vegetables, hemp, and flax, as well as dairy cows. Other corporate and independent farmers harvested the hay and sold it for such diverse uses as feed, mulch, ice-house insulation, traction on sandy roads, and packing material for glassware, pottery and fruits, as well as for making wrapping and butcher paper. In South Jersey, the Cedar Swamp Creek Meadow Company of Cape May similarly operated from at least 1815 until September 1924. [22] The Abbott Meadow Company, established in 1895 in Salem County, combined three older businesses: Causeway Meadow Company, Denn's Island Meadow Company, and Wyatt Meadow Company. They consolidated to simplify the repair of banks/dikes that were regularly destroyed by the tides. Abbott Meadow continued a tradition of growing timothy and grazing cattle in the fields after harvest; it operated until the 1920s. [23]

In 1845 the twenty-room brick, Federal-style Tide-Mill Farm House (Fig. 49), about two miles from Salem, was erected by George Abbott, a prominent Quaker and dairy farmer. In 1872 his son, also George Abbott, used the farm as the foundation of Abbotts Dairies; the cows grazed along the river in reclaimed fields that have long since disappeared. Abbott realized the need to ship the milk without its spoiling, and through experimentation discovered that milk stored in an ice house would remain cool elsewhere by wrapping the milk cans with insulating jackets made from wool blankets. Thus the milk could be shipped as far away as Cape May and Philadelphia. Abbott also devised a system of cooling and aerating milk: placed in large concrete troughs, surrounded by ice, the milk was stirred with long paddles connected to a long board placed atop the trough. Evidence of apparatus such as this is found in the basement of the Tide-Mill Farm House.

|

| Figure 49. The Abbott Tide-Mill Farm House (1845), replaced the earlier John Denn home, part of which may be enclosed in this three-story Federal block. |

Once the refrigeration problem was solved, Abbott turned to preventing the theft of milk from the cans, and providing it in a continuous supply. The first was corrected by his invention of a safety top and seal. The latter improved when Abbott established a receiving plant in Mannington, where he sold his neighbor's milk as well as his own. In 1876 the Abbotts Dairies (Fig. 50) business expanded rapidly through exposure at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition and his supplying of milk to Green's Hotel in Philadelphia. Abbott extended his dairy routes from Mt. Holly to Cape May in South Jersey, to Philadelphia; eventually divisions opened in Delaware. The company diversified to sell ice cream, butter, and other dairy products. In the 1960s it merged with Fairmont Foods of Omaha, Nebraska. The farmhouse and outbuildings at Tide-Mill Farm today are owned by George Abbott and Edward Abbott Jr., great-grandson of the founder, who is currently working to restore the property as well as a collection of company memorabilia. [24]

|

| Figure 50. Abbotts Dairies trucks were among the innovative techniques the family it merged with employed to modernize and expand the business. New Jersey: Life early 20th century. |

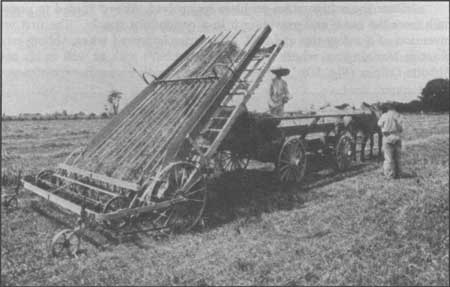

Salt-hay farmers worked together during the annual, one-week period devoted to cutting and stacking the grass—despite independent ownership of meadows. [25] The oxen and horses that pulled the wagons (Fig. 51) were equipped with broad leather mud-shoes that enabled them to walk on the marsh more easily, though they were still mired often. Once the hay was cut and stacked, farmers loaded it onto flat-decked, shallow-draft scows that awaited on a nearby waterway. One type of scow was typically 33' long, 12' wide, and about 3' deep; at times they were pulled by men walking along the bank, or pushed in the tradition of canal boats by men using 15' poles. By about 1950, power motors propelled the scows, just as tractors and hay balers replaced animals. [26]

|

| Figure 51. Horse-drawn wagons, as at Roadstown, hauled salt-hay loaders before mechanization; mired horses were often destroyed. New Jersey: Life, early 20th century. |

By the 1920s, the use of salt hay began to decline and the meadows grew obsolete. Glass companies such as Gayner Glass of Salem replaced it with cardboard as a packing material. Lack of labor and the increased value of muskrats, which thrived in the salty meadows, contributed to the decreased harvesting. Salem's meadows were the first in the three-county area to decline compared to Cumberland and Cape May where they were worked longer, and salt hay remained a profitable crop into the 1960s. "From Fortescue to the southern boundary of Cumberland County, there are roughly 10,000 acres of diked marsh. In Cape May County, in the vicinity of Dennisville, Goshen and Eldora, there are about 2,000 acres of salt marsh." [27]

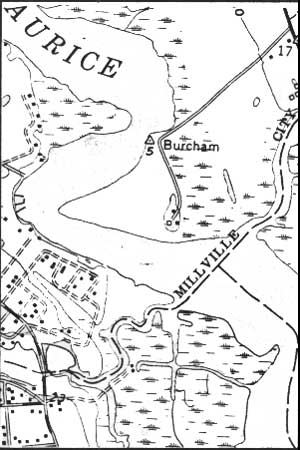

Today, the few farmers who continue to harvest salt hay are found in Cumberland and Cape May counties. One property that continues to exemplify this technology is the Burcham Farm outside Millville (Figs. 52-53). Although the Burcham House was built between 1869-70, the thirty-five acre site—a designated Century Farm and one of the few extant dike farms in the area—has been reclaimed since the early nineteenth century. Dikes made of earth, tires, and concrete rubble prevent the Maurice River's tide from eroding the near-island tract where twins Janice and Jeanette Burcham grow timothy, vegetables, and raise a few sheep, pigs, and geese. Sluice gates and drainage ditches (Fig. 54) are used to keep water off the property. Until the last thirty years, the Burcham's neighbors maintained similar properties, but they disappeared after the dikes and sluices broke down.

Although the Burchams could grow salt hay today, it would be unwise since the farm's drainage system has allowed the land to become arid and conditioned enough to support a better grade of hay and crops. Salt-hay farmers, however, use a system of embankment and drainage based upon the same principles that the Burcham family has employed for more than 100 years. The process of reclamation, however, is not as intensive, since salt hay is a lower grade of grass that can stand inundation by salt water.

|

| Figure 52. Aerial view, Burcham farm, a near-island triangle and probably the last working dike farm on the Maurice River; the strip of land (foreground) is all that remains of the adjacent dike farm. Wettstein, ca. 1950. |

|

| Figure 53. U.S.G.S. map showing Burcham farm and its tenuous relationship to the Maurice River. |

|

| Figure 54. Sluice gates around a drain pipe let water escape from fields at low tide; as the tide rises, the gates press shut so as not to flood the fields. Sebold. |

Fertility was the reason farmers continued to reclaim the marshes for farming until the mid twentieth century, though some used more conventional methods to increase production. Between 1810 and 1900, growers emphasized the care and fertilization of soil, and crop rotation. In addition to greater range, the number of farms increased while their size decreased, and more farmers turned to growing produce, and raising dairy cows and poultry. Revolutions in transportation and food preservation—canning and freezing—increased profit margins. Competition expanded as farmers farther away gained access to new markets via railroads and, later, trucking.

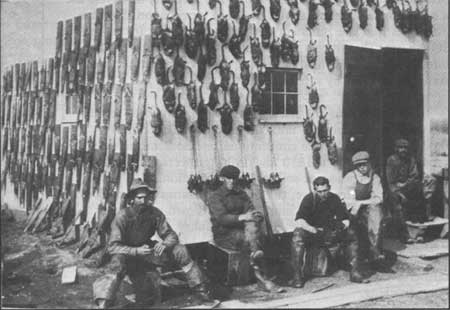

Two natural inhabitants of the salt marsh—one friend, one foe—have historically generated related activities here. Muskrats, which nest here in abundance, are trapped and sold for the hides as well as the meat (Fig. 55), which is prepared like other game. Since the seventeenth century, there have been efforts to diminish the menacing mosquito population. Pest control was codified under Franklin Roosevelt's Works Progress Administration in the 1930s when the U.S. Army established Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps in Cape May and Cumberland counties. The men here were charged with mosquito-control by way of digging ditches and draining swamps. One camp was located near Fairton and another was located at the present location of the Cape May County Mosquito Commission. Two CCC barracks are extant at the latter site, which also housed German prisoners of war during World War II.

|

| Figure 55. Muskrat skins dry on the wall of a trapper's shed; the animals were sought for their meat and skins. New Jersey: Life early 20th century. |

Fruit and Vegetables

In Cape May County, many farmers initially raised crops and dairy cows to meet the demand of oceanside resorts; this dwindled during the twentieth century when hotelier operations enjoyed greater and less-expensive transportation options, ie. shipping via rail and water. Agriculture—especially truck and dairy farming—continued to play a significant role in Cumberland and Salem counties. Truck farming consists of growing vegetables and fruits that were taken to the urban markets in Philadelphia, New York and elsewhere by horse-drawn wagon, railroad, and later trucks.

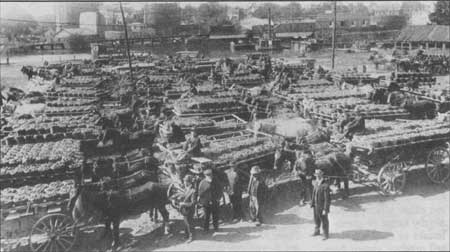

Despite the fact truck farming did not become a major influence until the mid to late nineteenth century, the crops grown here season after season were introduced much earlier. Europeans brought the knowledge of several vegetables with them, and in turn learned from the Indians to grow corn, squash, and beans. With Robert Johnson's promotional assistance, tomatoes became a profitable crop in Salem and Cumberland during the 1800s (Fig. 56). Farmers from all three counties also raised wheat, rye, corn, peas, beans, and hay; livestock included horses, milk cows, sheep, and pigs. [28]

|

| Figure 56. Farmers with their wagons filled with tomatoes await the boats that will ship them down the Cohansey River and beyond to urban markets or canneries. New Jersey: Life early 20th century. |

With the advent of the automobile in the first decades of the twentieth century, South Jersey became the largest truck-farming area in the state. Truck farmers grew many of the same vegetables and fruits—especially tomatoes—beans, onions, green peppers, fall lettuce, and berries as had their ancestors in the nineteenth century. Due to South Jersey's proximity to Philadelphia, much of it was exported via the West Jersey and Seashore Railroad; some farmers, however, continued to transport by wagon. Scows and barges carried tomatoes to Baltimore canneries and returned loaded with stable manure for fertilizer; dairy products were also shipped to Philadelphia and the seashore resorts. This method of transportation eventually became illegal due to stricter sanitation codes. [29]

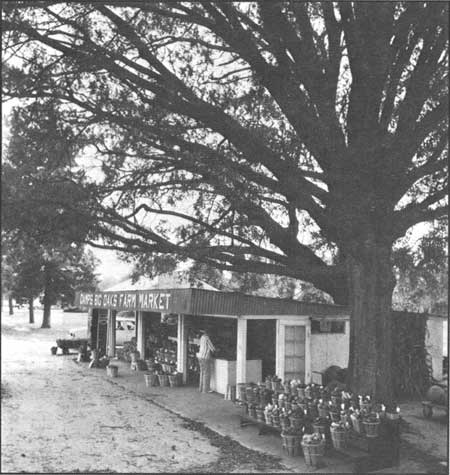

Besides commercial sales, this produce was sold locally from roadside stands, as early as the 1920s (Fig. 57). Roadside markets or stands continue to be a common sight in the rural areas of South Jersey today, especially along main roads such as Route 49, Route 47, and Buckshutem Road. They are either affiliated with nearby farms or greenhouses or they appear to sell produce grown from outside the area; in some instances, the peach orchard or vegetable fields are located next to the roadside stand, which is located in front of the farmhouse. There are a handful of definable forms that these stands take: the temporary pole-shed type of structure with modest and movable shelving; a gable- or shed-roofed building that is largely open on the front facade, of which Camps Big Oaks Farm Market is an example (Fig. 58); or is enclosed but features a continuous shed roof; and a structure like the aforementioned, with rambling additions of flat or slightly sloped roofs supported by plain posts. In some cases, the roof is extended off the side facades, and a new "exterior" is created by attaching chicken wire to the roof supports; floors in most are poured concrete. While the older roadside stands are made of wood, more often than not painted white, the more modern examples are constructed of corrugated metal.

|

| Figure 57. Roadside market, Fairton (early 20th century), is simple but more stylish—with awning and lattice posts—than stands today. New Jersey: Life. |

|

| Figure 58. Camp Big Oak's Market, near Port Elizabeth, is a partially enclosed utilitarian structure with a shed roof. |

Farm Labor

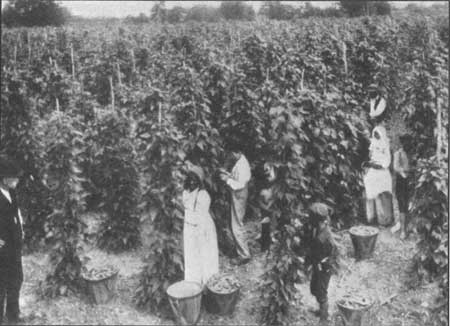

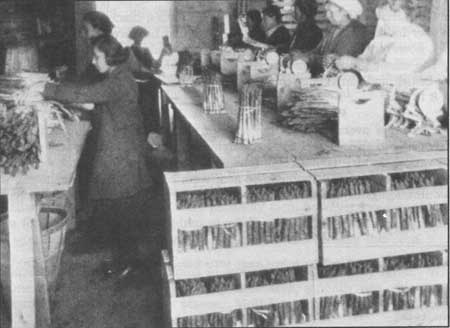

Produce was planted and picked by hand (Fig. 59) during the nineteenth century by any form of labor available; many farmers employed their children, wives, tenants, and hired hands. At the turn of the century, farmers began to hire local workers and migrant laborers from the early spring to late fall. From the 1920s until recently, the migrant force was mainly composed of Italians and blacks; workers were primarily men, however, poor economic conditions often forced the wives and children to work, too. In one asparagus-packing plant (Fig. 60), only women appear to be charged with bundling and binding this crop.

|

| Figure 59. Crops were hand-picked by men, women, and children, as here at a bean field near Port Norris. New Jersey: Life, early 20th century. |

|

| Figure 60. Produce, including asparagus, was hand-picked by a female workforce at this Fairton farm. New Jersey: Life, early 20th century. |

Italian families came from Philadelphia to work on truck and berry farms. Whether they stayed in one locale or moved around during the season, a family was often pald as a single unit—an estimated $1,000 or so per season. Most farmers provided meager housing on their property. Some of the Italians who stayed in South Jersey on a year-round basis rose from laborer to farm operator and property owner. In some cases, those who stayed in South Jersey helped farmers recruit more Philadelphia Italians each spring. Padrones received a sum for each person they brought to the farm; during planting and harvest, padrones worked in the fields as supervisors or bosses. Laborers found jobs through the padrones or private and government-run employment agencies that placed farm help in New Jersey from New York, Philadelphia, and elsewhere in New Jersey. [30]

Unlike Italians, many black migrant workers came great distances to work in New Jersey, most from as far south as North Carolina and South Carolina. After the season, some returned home while others settled in New Jersey. In Salem and Gloucester counties, black migrant workers were preferred over Italians because they spoke English and had previously worked on farms. Sometimes, however, Italians forced blacks out of the market because they would accept lower wages. [31] The ethnic groups found on truck farms included Poles, Russians, Germans, Austrians, British and Canadians—though they represent very low numbers. Workers ranged in age from 8 to 73. [32]

The laborers' average day in the summer was ten hours, in the winter eight. Most laborers returned to their homes in Philadelphia or other cities while few stayed to do minor chores on various farms. Living conditions were poor for most migrant workers throughout the early twentieth century. Some single men were boarded in the farmhouse, while others occupied outbuildings or abandoned railroad cars. [33]

Men accompanied by families were at first given one-room wood shacks with a single door on the gable end, but by the 1920s, some farmers began to supply cabins for the working families. These were a one-story frame or concrete block, typically 14' x 40', containing three rooms. Other housing units of the 1920s consisted of a long, frame, gable-roof structure with eight bays and four separate units; these units were two piles deep with an extended roof and porch. There was no water or plumbing, so cooking and washing tasks took place outside; families also were given garden plots and were allowed to keep some farm animals. Each unit held forty-seven people. [34]

The conditions of the migrant workers remained virtually the same until 1945 when the Migrant Labor Act was passed by the New Jersey Assembly. This act created an independent state regulatory agency, the Migrant Labor Board, which was composed of members from seven state departments. The agency established migrant labor policy and approved all rules, regulations and procedures regarding migrants. In 1959, the Migrant Labor Board proposed a law that would require farmers to "install hot water and heating facilities in the housing provided them." The board, however, generated controversy with the farmers over the matter; farm organizations feared that the improvements would cost the average farmer between $2,500 and $5,000. Despite these figures, the Migrant Labor Board was able to require farmers to abide by its regulations. The bill proposed by the farmers to bypass these rules was vetoed by Governor Meyner in 1960. During the controversy, however, Commissioner Male of the Civil Service Commission toured farms in various New Jersey counties and found that the farmers in Camden, Gloucester, Cumberland, Cape May, and Salem counties had been exemplary in complying with the Migrant Labor Board regulations. [35]

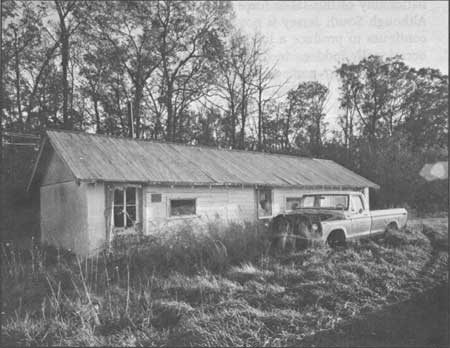

Today's migrant-worker dwellings are much the same (Fig. 61): frame or concrete block with a gable roof and no ornamentation. The number of housing units per structure ranges from one to five. The buildings are usually placed in groups of three or more, in a square layout with an open yard in the center. It is not uncommon, however, to find single structures or several placed haphazardly. Despite their less-than-desireable furbishments, migrant workers' housing today has running water and electricity.

|

| Figure 61. Migrant-worker housing is generally very basic, with running water and electricity introduced late in this century. |

Today, truck farmers continue to grow many of the same crops as did their forebears at the beginning of the century. They also continue to employ migrant workers, though the nationality of this labor force has shifted to Hispanics of Mexican or Puerto Rican heritage. Although South Jersey is now noted mainly for its fruit and vegetable crops, the region continues to produce a limited amount of salt hay, which is still used for packing, mulch, and occasionally fodder. In the Port Norris area, the hay is used by a one-person rope factory and a coffin-mattress company. In addition, the region's resources still support trappers and dairy and sod farms on a small scale.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

new-jersey/historic-themes-resources/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 14-Mar-2005