|

National Park Service

Historic Themes and Resources within the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail Route Southern New Jersey and the Delaware Bay: Cape May, Cumberland, and Salem Counties |

|

CHAPTER 5:

INDUSTRY

Industry in South Jersey has historically centered around the natural resources of the area: Waterways powered mills and iron foundries, fine sand allowed for widespread glass manufacturing, swamps and marshes preserved felled cedar that was used in the manufacture of durable building materials, and abundant vegetable and fruit crops made way for innovations in food preservation.

During the colonial period, settlers in South Jersey utilized the resources of the area not only to create a self-sufficient economy for themselves, but also to facilitate the break away from the British government. With the products made from iron foundries, mills, and glass factories, the colonists no longer relied upon agriculture as a single source of income. The early industries in South Jersey include: glassmaking, ironworks, gristmills, sawmills, cedar mining, charcoal burning, and brickmaking. (The numerous industries associated with maritime activities are addressed in Chapter 3.) Many of these enterprises were sustained well into the nineteenth century, though others did not survive the industrial revolution.

Glassmaking

The glass industry is one of the oldest and most successful industries in South Jersey—and one of the few in the area that remains strong. South Jersey was the natural setting for a widespread glass industry due to the abundance of sand, forest, and navigable waterways. One of Salem County's celebrated roles in history is that it is home to the first successful glass factory in the nation.

In 1738 Caspar Wistar, a German immigrant and Quaker, bought more than 100 acres of woodland near Alloway in Salem County because he realized the quality of the sand and abundance of wood at his disposal. A year later Wistar had laid out his new glass factory, a complex composed of a cordage pot, glass house, general store, workers' housing, and his mansion. The last three were essential, as the closest town was six miles away. Moreover, Wistar had more influence over his workers if they lived in housing he provided. [1]

Wistar also needed professional glass blowers, and he willingly made them partners in his firm. He invited Caspar Halter, Johan Halter, Johann Wentzell, and Simon Greismeyer from Germany. In exchange for their glass formulas, he provided one-way passage, land and dwellings, servants, and one-third of the company profits. [2] The town became known as Wistarburgh and its product, Wistarburgh glass.

Wistar's son, Richard, eventually took over the company, which relied upon skilled glassmaking immigrant labor. Fine glass does not seem to have been the main variety made by Wistar, though such luxury goods may not have been recorded—to evade British law. Glass manufacture was illegal in the colonies, but as long as Britain thought it presented no competition, Wistar was left alone. The government did investigate, however. In 1768 Lord Grenville, in an effort to enforce the Townsend Acts under which the making of glass was restricted, inquired to Benjamin Franklin about any such manufacturers in the colonies. Franklin's son William, then governor of New Jersey, replied that the Salem County "Glass House . . . made a very coarse Green Glass for windows used only in some of the houses of the poorer sort of People." [3]

In 1769, Richard Wistar advertised in the Pennsylvania Gazette for the following:

Made at the subscriber's Glass Works between 300 and 400 boxes of Window glass consisting of common sizes 10x12, 9x11, 8x10, 7x9, 6x8. Lamp glasses or any uncommon sizes under 16x18 are cut on short notice. Most sort of bottles, gallon, 1/2 gallon, and quart, flail measure 1/2 gallon cafe bottles, snuff and mustard bottles also electrifying globes and tubes &c. All glass American Manufacture[rs] and America ought to encourage her own manufacture. [4]

The demise of Wistarburgh came with the Revolutionary War, though exactly why and when is unknown. Some historians speculate that it closed in 1776 because the workers were drafted by the American army. Four years later, Richard Wistar still sought to sell the business:

The Glass Manufactory in Salem County West Jersey is for sale with 1500 Acres of Land adjoining. It contains two furnaces with all the necessary Ovens for cooling the glass, drying Wood, etc. Contiguous to the Manufactory are two flattening Ovens in Separate Houses, a Storehouse, a Pot-house, a House fitted with Tables for cutting of Glass, a Stamping Mill, a rolling mill for the preparing of Clay for the making of Pots; and at a suitable distance are ten Dwelling houses for the Work men, a likewise a large Mansion House . . .; Also a convenient Storehouse where a well assorted retail Ship has been kept above 30 years, is as good a stand for the sale of goods as any in the Country, being situated one mile and a half from a navigable creek where shallops load for Philadelphia, eight miles from the county seat of Salem and half a mile from a good mill. There are about 250 acres of cleared land within fence 100 whereof is mowable meadow, which produces hay and pasturage sufficient for the large stock of Cattle and Horses employed by the Manufactory . . . . For terms of sale apply to the Subscriber in Philadelphia. [5]

Though the Wistarburgh glassworks closed, its success—coupled with the abundant natural resources—encouraged other factories to operate here. Almost a century later, Salem boasted four glassworks: Hall, Pencoast, and Craven/Salem Glass Works; Holz, Clark and Taylor; Gayner Glass Works; and Alva Glass Manufacturing Company.

Other prominent glass factories were based in Port Elizabeth, Bridgeton, and Millville where there was access to sand, woods, and waterways. The Eagle Glass Works, built in 1799 in Port Elizabeth, was the third glass house established in New Jersey. James and Thomas Lee, with a group of Philadelphians, founded Eagle Glass on the Manumuskin Creek, a branch of the Maurice River. The company hired several members of the Stanger family, highly skilled bottle-makers, though the first furnace was devoted only to making window glass. [6] From 1816 through the 1840s, another well-known German glassmaking family—the Getsingers—rented Eagle Glass. After several subsequent owners, the glassworks was sold at auction in 1862; it did not operate long, however, and was abandoned by 1885. [7]

The Union Glass Works was established between 1806-11 by Jacob and Frederick Stanger, and William Shough; Randall Marshall joined them as a partner in 1811. The Stangers and Shough served as both managers and blowers, working with five other blowers to make medicine vials. Business problems arose from the start, however. In December 1811 the building burned and it was not rebuilt until late 1812; two years later the company was dissolved and divided into four equal shares, while all the blowers except for the original partners departed. By 1816 the furnaces were split up; one run by Marshall, the other by Jacob Stanger and Shough. Marshall soon moved, and Union Glass Works closed in 1818. [8]

After setting up the Eagle Glass Works in Port Elizabeth, James Lee established the first glassworks in Millville in 1806, on the Buck Street site which was later run by Whitall Tatum and now is home to the American Legion. Known as Glasstown, Lee produced window glass here. In 1836 the firm Scattergood, Booth and Company bought Glasstown. Soon after, Scattergood married Sara Whitall, sister of a sea captain; when Captain Whitall left his position, he invested his savings in Glasstown and a dry goods business (that would later fail). Whitall also married Mary Tatum, a Quaker, and they moved to Philadelphia leaving a brother, Franklin Whitall, in charge; Scattergood retired in 1845 and shortly thereafter the name of the business became Whitall, Brother and Company. Edward Tatum joined them; then when Franklin Whitall left in 1857, the name was changed again to Whitall Tatum and Company—which was so successful that it opened a New York office run by C.A. Tatum. Finally, in 1901 it was incorporated as the Whitall Tatum Company. [9]

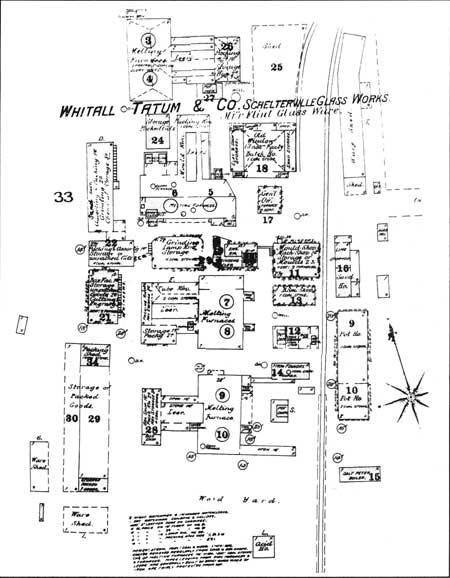

In addition to Glasstown, Whitall Tatum bought a glassworks on the south end of Millville in an area called Schetterville (Fig. 62). The hamlet originated in 1832 when Frederick and Phillip Schetter set up a furnace here. In 1844 Lewis Mulford, Millville's leading banker, along with William Coffin, Jr., and Andrew K. Hay bought the Schetterville property—then monopolized all the local timber that was used to fuel the glass furnaces in an effort to gouge Whitall Tatum. The latter refused to buy from Mulford et al., and imported wood from Virginia until it became prohibitively expensive—and there was no other choice. Today Foster-Forbes, a division of American Glass, owns this part of Whitall Tatum. [10]

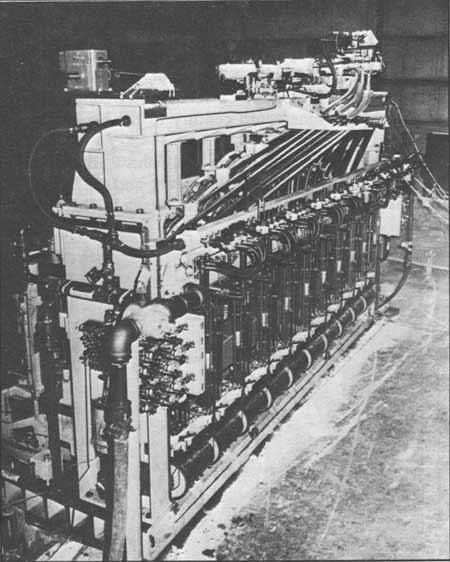

Whitall Tatum did more than become the first successful glass factory in Millville. By taking advantage of the railroad's arrival in 1863, it benefitted by a wider distribution area and the improvement of its product. Previously, Whitall had hired Thomas Campbell to make metal—rather than clay—bottle molds. After mid century Whitall Tatum would experiment with even more sophisticated mold-making methods, and in 1867 wood molds were introduced, which eliminated seam lines on the flint glass (Fig. 63). The bottles were used to contain perfume, medicine and prescriptions, spirits, and as vases. On their breaks, blowers made paperweights and other decorative pieces for their personal use and sale. [11]

|

| Figure 63. Maul Brothers' ten-section bottle-making machine, the first of its kind, was built in Millville. Wettstein, 20th century. |

Whitall Tatum was also the first glassworks to set up a chemical laboratory in which to experiment with the analytical control of formulas for batch mixes—which became indispensable to glass manufacturing. William Leighton's formula for lime glass, an improvement over ordinary flint glass, was utilized, and by 1883 the company operated ten flint-glass furnaces that produced 12 million pounds of lime glass annually. Lime glass allowed the blowers to create more impressive glassware because it emerged from the annealing ovens clear and brilliant and was easy to control. [12]

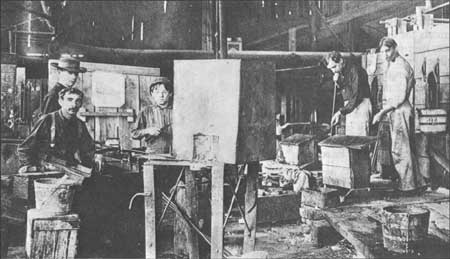

Whitall Tatum represented an impressive industrial scale in its nineteenth-century heyday. In 1899 it counted 460 employees, including 139 blowers, at Glasstown or the Upper Works; and 1,052 persons including 211 blowers, thirty-six lamp-workers, and 708 packers, at Schetterville/the Lower works. Besides blowers, there were packers, office workers, letterers and engravers, cutters, decorators, and apprentices who looked to become journeymen blowers (Fig. 64). [13]

|

| Figure 64. Whitall Tatum shop with workers blowing glass. Wettstein, ca. 1900. |

Dr. Theodore Wheaton, a physician who moved to Millville in 1883 to open a drug store, founded another glassworks in 1888. With a six-pot furnace and thirty-six employees, he hoped to specialize in bottles and glass tubing. In 1901, the company incorporated as T.C. Wheaton and Company, and by 1909 it employed 2,000 persons. In 1926 it was able to buy out a major competitor, Millville Bottle Works. Twelve years later Wheaton installed its first automatic machinery and it has steadily modernized its operations since. In 1966 the name was changed to Wheaton Glass Company. [14]

The presence of Wheaton and Whitall Tatum, along with several less-prominent glass factories, made Millville a center of glassmaking during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Bridgeton was a relative newcomer in comparison, hosting glass furnaces from the middle of the nineteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth.

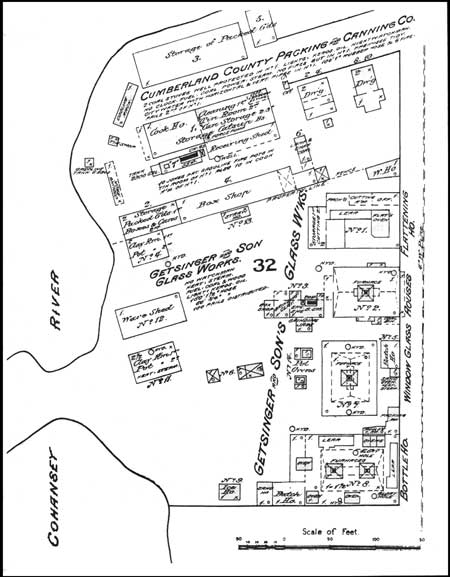

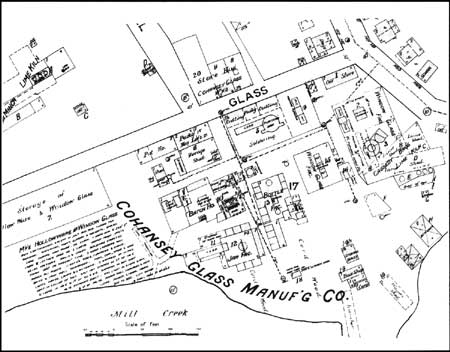

Nathaniel L. Stratton and John P. Buck started the Stratton, Buck and Company glass factory here in 1836 at Pearl Street and the river. Many of the flasks it produced were impressed with "Bridgeton, New Jersey." This company represented the single-largest business in Cumberland County for many years thanks to holdings of large tracts of land and a general store. With a disastrous fire and Buck's death in the 1840s, Stratton sold the company to John G. Rosenbaum, who operated it until 1846; he in turn sold it to Joel Bodine and Sons. After going bankrupt, the company sold to David Potter and Francis I. Bodine, who joined in the race to invent a reliable air-tight fruit jar. Although the Mason jar eventually became the most widely type used, Potter and Bodine patented one in 1858. In 1863, Potter sold his shares of the company to J. Nixon and Francis L. Bodine, who incorporated in 1870 as the Cohansey Glass Manufacturing Company (Fig. 65), makers of fruit jars and window glass. [15]

|

| Figure 65. Cohansey Glass Manufacturing Company site plan. Sanborn, 1886. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Bridgeton was home to more than seventeen glass factories, operating at various times. These included: Getsinger and Son (Fig. 66); Cumberland Glass Manufacturing Company/Clark Window Glass Company; More, Jonas, and More Glass Works; East Lake Glass Works/Hollow-Ware; Parker Brothers Glass Factory; West Side Glass Manufacturing Company Ltd.; Perfection Funnel Works; Glass-Bottle-Mold Factory; and Daniel Loder. Their products ranged from fruit jars and bottles to funnels and windows. [16]

Salem County also was home to several glass companies in the middle and late nineteenth century. The Salem Glass-Works in the City of Salem was established in 1863 by Henry D. Hall, Joseph D. Pancoast and John V. Craven. In 1882, after the deaths of Hall and Pancoast, sole proprietor John Craven sold partial interest to his brother, Thomas J. Craven, and the company became Craven Brothers. The firm had two factories: one on Fourth Street and the other on Third Street. Both factories employed approximately 350 people and manufactured bottles and fruit jars. [17] Another competitor, Quinton Glass Works, operated out of Quinton's Bridge in Salem County. D.P. Smith, George Hires Jr., John Lambert, and Charles Hires started the company in 1863. By 1871, after the retirement of Smith and Lambert, the Hires brothers changed the name to Hires and Brother. Five years later, William Plummer, Jr., joined the firm and again the name changed to Hires and Company. Employing 150 people, the company processed window, coach, and picture glass. In addition, the company had a gristmill and a general store. Today, Anchor Glass Company still operates on Griffith Street in Salem. [18]

As automation and mechanization came to dominate early twentieth-century manufacturing, many of South Jersey's glass factories disappeared. Those that survived were the best able to modernize: Of the nineteenth-century factories, only Wheaton Industries endures today, but the buildings of the Lower Works of Whitall Tatum are now used in part by Foster Forbes. Wheaton Industries has also attempted to preserve the knowledge of the technology previously used in its glass-blowing demonstrations at Wheaton Village in Millville; the Village also houses the Museum of American Glass.

Canneries/Produce Packing

The abundance of locally grown produce spurred the development of South Jersey's canning industry, and in turn furthered the science of food preservation. In 1795 Nicholas Appert endorsed the use of glass containers as most resistant to air, as well as the need to sterilize them first in boiling water before filling. [19] Appert paved the way for other experiments with food preservation.

In 1810 a patented European container of tin plate, hermetically sealed, arrived in the United States. Once these "plumb cans" were made here, more people began to use them—such as Ezra Dagget and Thomas Kensett who canned salmon, lobsters and oysters in New York City. By 1830, canned seafood was common in France and Nova Scotia, as well as Eastport, Maine, and Baltimore, Maryland. Experimentation with tin cans continued, and by the 1840s vegetables were commonly packed in them. The canning revolution arrived in New Jersey when Harrison W. Crosby of Jamesburg successfully processed tomatoes in tin cans in 1847—the same year a canning factory opened in Monmouth County. [20] It was a model that, concurrent with pasteurization, and the discovery that calcium chloride added to boiling water increased its temperature and reduced cooking time, enticed more New Jerseyans to open canneries. In the southern part of the state plentiful tomato crops were an added incentive.

|

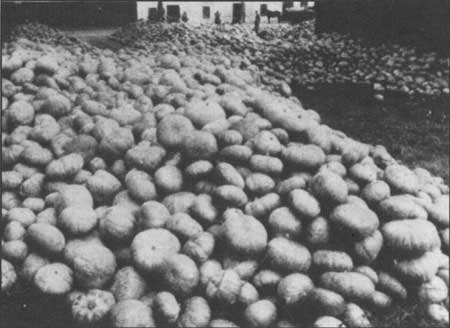

| Figure 67. Squash at a Bridgeton cannery. New Jersey: Life early 20th century. |

The first canning factory in Cumberland County began in the 1840s at the home of John E. Sheppard, who lived conveniently near the Quaker meeting house where towns-women helped with the labor. Like many early canneries, Sheppard made the cans on the premises. Local historians surmise that Sheppard also did some canning in a house near Sheppard's Mill, two miles outside of Greenwich. [21]

Over the century or so from 1840 to 1942, Cumberland County hosted about twenty-eight different canneries at various times. The greatest influx of new canneries and related businesses occurred from 1860-90, when approximately twenty-three new canneries began operating: thirteen in Bridgeton, two each in Fairton, Cedarville, and Greenwich; and one each in Bacon's Neck, Bayside/Caviar, Millville, and Newport. [22]

Some prominent canneries built during that thirty-year period were: Stein Edwards, John E. Diament Company, Steven's Canning Factory, and R.S. Watson and Son. Associated industries include the Ferracute Machine Company and Ayars Machine Company. The former, under the direction of Oberlin Smith, made presses for the tin can components; the latter supplied tin cans and machines that aided in the filling of the cans. [23]

Stein Edwards established the first cannery in Bridgeton in 1861, named after himself. Six years later he sold it to Warner, Rhodes and Company and in 1888 it was merged into the West Jersey Packing Company, which made its own cans and packed about 700,000-1 million units per year. Warner Rhodes specialized in tomatoes and peaches, but it also packed lima beans and sweet potatoes, and manufactured ketchup and salad dressing. [24]

West Jersey Packing Company and the presence of other canneries led several Bridgeton residents to experiment with canning machines. In 1887 J.D. Cox took a sample of his new hand-capping machine to Baltimore; he thought the device might be applicable there since most of its canneries made their own containers and caps, which they in turn sold to rural canneries. This machine revolutionized the canning industry in that it mechanized the closure process. By 1890 cans were being made automatically from sheet tin, and counted automatically as they went into shipping cars. These changes created less of a dependence on manual labor and thus, less chance that strikes or labor unrest would slow down production. [25]

By the turn of the century, a new can was developed that overtook the industry and further advanced food preservation here and elsewhere. The unsoldered unit, called the "sanitary" can, differed from predecessors by its rubber-sealed coating instead of a gasket, and double seams. The Max Ams Company of New York City, which packed and exported fish products to foreign countries, was looking for just such a can; one of the company's biggest suppliers was the caviar factory at Bayside. In 1904 Max Ams established the Sanitary Can Company in New York City, and two years later a branch office was opened in Bridgeton. [26]

Unlike Cumberland County, Salem and Cape May counties had fewer canning facilities—perhaps due to a limited number of glass and machine factories. Millville had at least three glassworks by the mid nineteenth century, as well as an iron foundry; Bridgeton had several glass companies and a machine factory. Greenwich also had a machine factory. Salem and Cape May counties do not appear to have had as many industrial resources.

The first canning factory in Salem County was Patterson, Ware and Casper. The exact year the factory began to operate is unknown, but it was established in 1862 or 1864, and it canned tomatoes, pears, peaches, beans, pineapples, peas, cherries, blackberries, and corn. [27] The factory was located on Church Street in Salem and was built by Theophilus Patterson, Richard B. Ware and Charles W. Casper. Unfortunately the business was unprofitable due to the high price of tin, management's inability to convince women to work in the factory, and the low price of tomatoes. Patterson, Ware and Casper operated only for a year. [28]

Production continued at the same site, however, under ownership of James K. Patterson and Ephraim J. Lloyd, and afterward by Patterson and Owen L. Jones. In 1882, when Patterson retired, Jones took over the company. By that time the factory had been located on Fifth Street for eight years. The year after Jones gained full ownership, James Ayars, owner and operator of Ayars Machine Shop of Greenwich, left his business to go into partnership with Jones. [29]

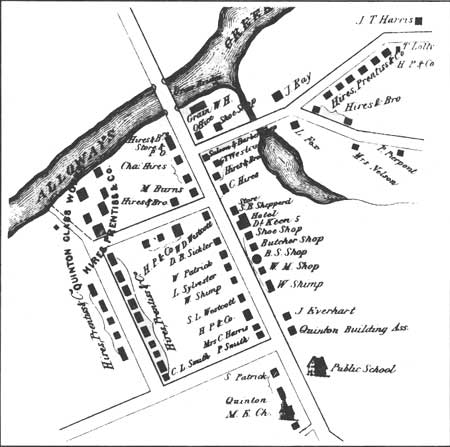

Fogg and Hires was another prosperous tomato cannery in Salem County. Located in Quinton (Fig. 68), this cannery was established by Lucius E. Hires and Robert S. Fogg in 1884. The first factory, located on East Street, prospered so the first year that a second factory was erected on the bank of Alloways Creek. A decade later the company upgraded the second cannery and closed the first. Fogg and Hires also ran branches in Pennsville and Hancock's Bridge. In 1924 Fogg died; Hires continued to run the business until his death in 1937. William Patton then bought the company, which continued to operate until 1946. [30]

|

| Figure 68. Map of Quinton's Bridge showing the proximity of the glassworks, cannery and company-owned housing. Atlas, 1876. |

Other late nineteenth-century canneries included: Starr Brothers, Mason Pickling Company, Salem Canning Company, Chew and Bilderback, Bassett and Fogg, Farmers' Cooperative Canning Company, Aldine Canning Factory, and H.J. Heinz. These and others were located in Salem, Hancock's Bridge, or Quinton.

Cape May County appears not to have had as many canneries as its neighbors, and those few were managed by companies based in Salem or Cumberland counties. One of these was owned by the Stevens family. The original, established by William L. Stevens in 1888 in Cedarville, was so successful that a second branch was opened in Eldora in 1904. Two years later a third branch, the Goshen Canning Company, opened; both the Eldora and the Goshen sites were in Cape May County. In 1908 the business incorporated and the Cedarville plant was established as company headquarters. After several family owners, the last Stevens cannery closed in 1938. Among its contributions to the canning industry were the Stevens Can Filling Machine, which improved the process of canning tomatoes, fruits, and meats through automation, and establishment of a canning operation at the Leesburg State Prison Farm. [31]

Another cannery with facilities in Cumberland and Cape May counties was the John E. Diament Company, whose first cannery was built in Cedarville, followed by one in Tuckahoe in 1903 (the latter is out of the NJCHT area). The buildings at the Rio Grande Packing Company had been erected for a molasses mill or sugar manufacturing plant in 1881, called the Rio Grande Sugar Company. It closed when plans to grow sorghum and process it as sugar failed. Other Rio Grande factories included Garden State Canning Company, the Mt. Holly Canning Company, and the Rio Grande Preserving Company. Nearby South Dennis was also home to several canneries, among them the Salem Supply Company and Van Gilder and Company. [32]

Canneries continued to prosper in South Jersey well into the twentieth century. Phillip J. Ritter Company made ketchup and canned vegetables in Bridgeton for nearly a century. It and other canneries were essential industries during both World Wars. In World War II, the company hired German prisoners to fill the places of workers who had been drafted. In other instances migrant workers were hired to help process the tomatoes and other vegetables; many of them lived in Ritter Village. Other branches of P.J. Ritter Company (founded in Kensington, Pennsylvania) were located in Bristol, England; Newark, New Jersey; and Ellendale, Delaware. The site of this canning facility is now owned and operated by the 7-Up Bottling Company. The site was also historically shared with the Cohansey Glass Manufacturing Company. Some nineteenth- and twentieth-century buildings appear to be intact but require additional investigation. [33]

Today, canneries remain an important part of South Jersey industry. Two important events helped determine the success of one enterprise, Seabrook Farms, several miles north of Bridgeton. First, company founder Charles F. Seabrook invented a quick-freezing process that is still used by frozen-food companies today for much name-brand produce. Second, Seabrook Farms owns the land on which most of the products grown are canned and frozen. Historically, in the paternalistic tradition, it also built worker housing and stocked a company store, some of which is still extant.

Bog Iron/Iron Foundries

The predecessor to post-industrial revolution-era iron making is found locally in the bog iron industry that was significant in Ocean, Burlington, Camden, Atlantic, and Gloucester counties. Several ironworks were historically located in Cumberland and Salem counties, as well. As early as 1719, Britain feared the potential competition that would rise from a viable iron industry in the New World. Laws were subsequently passed that prohibited the establishment of foundries or the manufacture of such iron wares as sows, pigs, or cast-iron, which could be converted into bars or rod irons and then into objects. The laws were later repealed, but future efforts to regulate the industry came in the form of taxes on the ore produced. In 1750, the duty on American iron was repealed, but owners of slitting or rolling mills, plating forges, and steel furnaces built before that year had to submit an inventory of its buildings and equipment to the county sheriff and the secretary's office in Burlington. [34]

Associated with iron manufacture was charcoal burning. Charcoal created the intense heat that iron forges and glass furnaces required. Thus, iron foundries were best located along forests for a consistent supply of wood, and close to the bogs or swamps that might contain ore. One furnace required approximately four square miles of woodland to fuel the ironworks during its lifetime—and all early ironworks were situated along rivers or creeks in unsettled and heavily wooded territory. [35]

Bog, or meadow, ore is found throughout New Jersey and is most prominent in the southern counties. Charles Boyer, in New Jersey Forges and Furnaces best describes the process by which decaying vegetation and soluble iron salts interact:

Bog ore is a variety of limonite ore and is present in low lands and meadows where there are beds of marl and strata of a distinctly ferruginous nature. The waters, highly tinged with vegetable matter, percolating through these deposits take into solution a considerable quantity of iron in the form of oxide. As these waters emerge from the ground and become exposed to the air, the iron solution decomposes and deposits a reddish muddy "sludge" along the banks, in the coves of the water courses, or in the beds of the swamps or wet meadows. . . . The deposit in time soon becomes of sufficient thickness to be classed as a bog-ore bed. [36]

As long as sufficient vegetation exists to act with the soluble iron salts, bog iron beds will continue to replenish themselves, a process that takes about twenty years from the time ore is removed until the new bed is thick enough for ore to be mined. [37]

Because many early ironworks were remotely situated, each sustained its own community or village, the most important feature of which was the furnace stack. This was a four-sided stone or brick block, "20' or more in height and 20-24' square at the base, tapering toward the top to about 16-20'." The high-roofed casting, or molding, house was in front of the furnace. Also nearby were the charcoal sheds, or coal houses, and the carpenter shop where molds and patterns for plowshares, pots, pans, stoves, fire backs, and water pipes were made. The workers' housing was a short distance from the furnace, near the iron master's house. Most communities had a school, church, and company store. Outside the community was often found the local tavern. [38]

The R.D. Wood and Company foundry, established in 1814, began as a complex like this on Columbia Avenue in Millville. Originally founded by David Wood and Edward Smith, it was first called Smith and Wood. Under the leadership of Wood, the foundry produced cast stove plates. In 1840 when Richard Wood purchased the company, he constructed two larger foundries that were capable of smelting 40 tons of iron per day. As R.D. Wood and Company, the foundry discontinued the practice of manufacturing iron itself, in favor of the specific task of casting gas and water pipes. The foundry, along with the Millville Manufacturing Company—also owned by Wood, across from the Wood Mansion and the company store—obtained its power from the Union Lake Dam. By the end of the nineteenth century, R.D. Wood and Company employed 125 people and earned approximately $350,000 annually. [39]

A year after the establishment of the Smith and Wood Foundry in Millville, Benjamin and David Reeves started the Cumberland Nail and Iron Company in Bridgeton. Located on the west side of the Cohansey River, this ironworks obtained its power from the nearby Tumbling Dam. Here the Reeves brothers manufactured nails. In 1824 part of the works was burned but the brothers rebuilt on a larger scale; by 1847 business had prospered to allow the company to build a rolling mill on the opposite side of the river. This mill operated a steam engine, which in turn heated the iron. Six years later the company moved to a site just north of the rolling mill where a large pipe mill had been erected. At this new site the company made wrought-iron, gas and water pipes, and nails. In 1856, after the death of Benjamin Reeves and the incorporation of Robert S. Buck into the company, the foundry became the Cumberland Nail and Iron Company. At the end of the nineteenth century, the company employed 400 men and produced 40,000 kegs of nails and 4 million feet of pipes yearly. [40]

Foundries in the NJCHT area, particularly Cumberland County, were numerous in the eighteenth century in remote areas. The earliest-known foundry was on Cedar Creek outside Cedarville. Local historians believe it existed before 1753, when an sale notice appeared in the newspaper:

The Iron-Works at Cohansie, in Cumberland County, with 1,000 acres of land, well timber'd; the forge house is 40' long and 30' wide with one fireplace already built, and a good head of water. Any person inclining to purchase the same, may apply to Samuel Barnes, living on the premises. [41]

In addition to being located on Cedar Creek, which was dammed to create several ponds for power, the foundry was located near a forest and a swamp. By 1789 it no longer existed and the ponds were used to run Ogden's Mill. Again, local historians believe the foundry folded due to the depletion of bog iron. [42]

Eli Budd built Budd's Iron Works in 1785 on the Manumuskin Creek. In 1810 his son, Wesley, and some Philadelphia associates erected a blast furnace where the old Cape May Road crossed the Manumuskin; together they became the Cumberland Furnace when Benjamin Jones purchased the site in 1812. After several changes in ownership, the furnace was sold to R.D. Wood in the middle of the nineteenth century. [43]

The ore used by Budd's Iron Works/Cumberland Furnace came from Downe Township until that supply was consumed. Then ore was brought in from Delaware and Burlington counties via ships that went up the Menantico Creek to Schooner Landing; from there the ore was taken to the furnaces by cart. According to an 1831 survey, two furnaces were associated with this property: One across from a dam located where the Big Canute branch joined the Manumuskin Creek, and the other a mile north of here. Stove plates may have been produced at Cumberland Furnace around 1812. [44]

The Ferracute Machine-Works, Cox and Sons' Machine-Works, and Laning's Iron Foundry in Bridgeton, as well as Hall's Foundry in Salem, all followed Wood's example and turned to only making and casting molds. The Ferracute Machine-Works was founded in 1863 by Oberlin Smith, an inventor who experimented with new metal presses and molds. Ferracute made foot and power presses, dies, and tools for cutting, embossing and drawing; as well as sheet-metal goods such as tinware, lanterns, lamps, and fruit cans. The bulk of its early business not surprisingly came from fruit-can presses, since the area was dominated by canneries that made their own cans. At that time the company employed approximately sixty men. By the twentieth century, Ferracute had turned to making presses and molds to meet the needs of heavier industries, including automobile and airplane parts. [45] In 1909 it employed 125 people. [46]

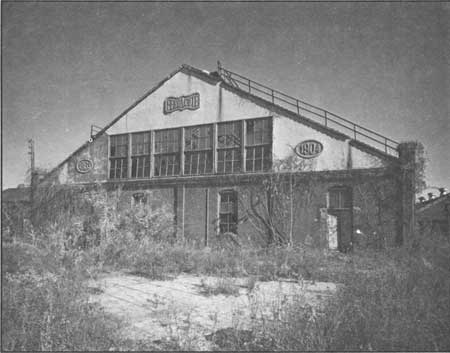

The 1904 Ferracute complex is extant and vacant today, adjacent to East Lake and the railroad tracks, though all or most of the machinery has been removed and all structures are in good-to-poor condition (Figs. 69-70). Smaller gabled brick buildings are adjacent. At the fore of the industrial site atop a slight hill is the elegant-but-deteriorating headquarters building. The eclectic composition combines Victorian elements of the Stick Style, Queen Anne and Tudor Revival in its irregular plan. The decorative brick structure includes a round tower with conical roof and flared eaves; various gable-roofed dormers and porches, decorative chimneys, gable trusses and Craftsman-like supports contribute to a romantic flavor that is a sharp contrast to the utilitarian industrial buildings behind it.

|

| Figure 69. Inventor Oberlin Smith started the Ferracute Machine-Works in 1863. In 1904 Ferracute moved to its present site after a fire destroyed the first complex of buildings. |

|

| Figure 70. This largest of the Ferracute buildings is structurally sound, but the presses and other equipment have been removed. |

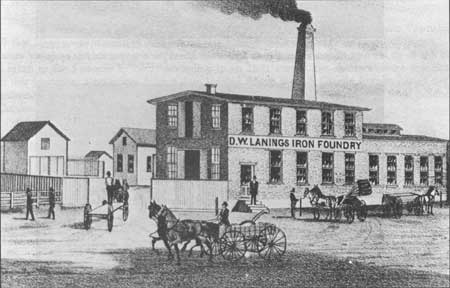

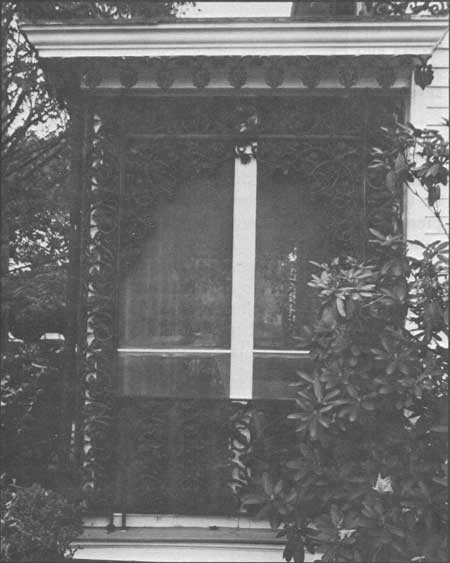

Laning's Iron Foundry (Fig. 71), established in 1869 under the control of David W. Laning, manufactured blacksmith's drills, iron verandas and fences, vessel wind lasses, plow-castings, and other castings (Fig. 72). This brick factory, adjoining the West Jersey Railroad Depot, employed twenty men at the end of the nineteenth century. Cox and Son's Machine-Works, also established in the 1860s, made steam-heating apparatus, steam engines and boilers, pipe-screwing and lapping machinery, stocks, dies, and cast and wrought-iron fillings. Originally located on the corner of Broad and Water streets, the factory moved to a new site on Water Street with a frontage of 250' on the Cohansey River. Proximity to the water allowed them to utilize steam power. [47] The foundry continued its operations well into the twentieth century employing approximately 160 men. [48]

|

| Figure 71. David W. Laning started this iron foundry in Bridgeton in 1869, and he operated it until his death in 1883. Atlas, 1876. |

|

| Figure 72. Intricate cast-iron architectural elements—porches, fencing railings—were produced at South Jersey foundries. |

In 1848 Bennett and Acton established a foundry on the corner of Fourth and Griffith streets. Much of the business consisted of making agricultural machinery. In 1862, the business passed to Acton after Bennett's death. Sixteen years later he sold the firm to Henry D. Hall who turned it into Hall's Foundry, which produced plumbers' castings, and drain and smoke pipes. [49]

Today little evidence remains of the iron industry in Salem and Cumberland counties, but for the exquisite ironwork found in the fences, cresting, and other architectural features that highlight church yards and older residential areas—Salem, in particular. The key to the success of many of these nineteenth-century foundries was their ability to take advantage of the economic possibilities made available by South Jersey's unique geographic location and combination of natural resources. Eventually, depleted woodlands and changing technologies contributed to their decline.

Mills

Gristmills and sawmills were among the earliest local industries, built on outlying creeks and rivers, and in Bridgeton and Millville where they marked the first sign of settlement. Tide mills powered by the ebb and flow of the creek waters existed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in Greenwich, Mill Creek, and Mannington Meadows. [50]

One of the earliest was Hancock's Sawmill, built in 1686 on Mill Creek (Indian Fields Run) in present-day Bridgeton. Richard Hancock also constructed a dam and mill here, which changed hands several times until 1807-08, when Jeremiah Buck bought them and built anew on Commerce Street. Ephraim Seeley built another dam and gristmill in 1700 north of the present dam on Commerce Street. When Buck bought Seeley's dam and mill he undertook a series of improvements. He built a new dam, thus enlarging the mill pond, and in 1809 he erected a new gristmill and sawmill. A decade later Buck's fortunes declined and Dr. William Elmer purchased the property; Elmer's heir later sold the sawmill, but continued to operate the gristmill into the late nineteenth century. These and other mills were especially important because they predicated the establishment of Bridgeton. Farther east, another dam and mill played a similar role in the development of Millville.

In the late eighteenth century the Union Company was started by Henry Drinker and Joseph Smith who purchased 24,000 acres near Millville. The company used the dam to power sawmills; the lumber was then floated down river where it was loaded on to ships bound for market. In 1795 Joseph Buck, Eli Elmer, and Robert Smith bought the Union property. Buck then planned the city of Millville—slated to contain mills and other industries fueled by water passing over the dam. Many mill and factory owners here gained access to the nearby waterpower by digging canals to their property.

Buck's plans for the city became reality when David Wood and Edward Smith established Smith and Wood Iron Foundry, as previously discussed. Wood's brother, Richard, added to the family prosperity by establishing a cotton mill next to the foundry in 1854. The business operated as New Jersey Mills until 1860 when a bleachery and dye house were added; this became Millville Manufacturing. Upon establishment of the bleachery and dye house, Wood then constructed a new dam, creating the largest manmade lake in New Jersey. The water power from the dam allowed the mill to produce its own electricity in the late nineteenth century. By 1870 the mill had 25,000 spindles, 500 looms, and 600 employees. Thirty-nine years later the number of employees had doubled.

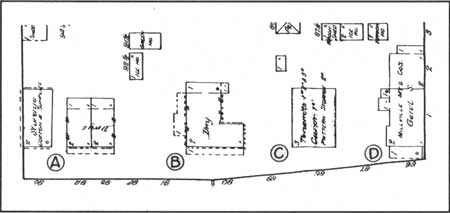

Many Millville Manufacturing employees lived in homes constructed by the Wood family in the surrounding area. Moreover, they shopped at the company store located on Columbia Avenue next to the Wood Mansion (Fig. 73). The company also constructed a wood bridge across the Maurice River to shorten the distance for those workers who lived on the western shore. Though the worker housing exists today, many of the industrial buildings associated with Millville Manufacturing do not. However, buildings connected with the foundry exist, including the pump house used by the cotton mill (Fig. 75). [51] Like Millville Manufacturing, Hires, Prentiss and Company of Quinton's Bridge provided housing for its workers. The two-family dwellings are intact along the Quinton-Alloway Road/Route 581.

|

| Figure 73. Wood Mansion was built by David Wood in 1804. Today the Wood family continues to use it as the headquarters for WaWa Markets, Inc. |

|

| Figure 74. Many of the employees of Millville Manufacturing lived in worker housing. This example is located on Foundry Street in Millville. |

|

| Figure 75. Now owned by Wheaton Industries, this complex of buildings includes the pump house once used by Millville Manufacturing Company. |

|

| Figure 76. Millville Manufacturing Co.'s: A) Two-family dwelling, B) Wood Mansion, C) Tenement housing, D) general store. Sanborn, 1886. |

Like Bridgeton and Millville, the mills elsewhere in South Jersey encouraged settlement, and provided jobs as well as independence from Great Britain. In 1692 William Forest built a water-powered gristmill at Mill Hollow in Salem County. Ten years later, John Mason of Elsinboro built a flour mill on Stow Creek; about the same time Samuel Fithian erected a dam and sawmill in Fairfield, his son John, who lived nearby, co-owned a gristmill. The Fithians' property was acquired by John Ogden, then in 1743 by David Clark who moved the gristmill to the main road in Fairton, bringing in water via a mill race. In 1759 the mill dam in Fairton was changed to its present location.

In Cedarville, Henry Pierson purchased a mill from William Dillis and John Barns in 1753, which henceforth changed ownership many times. Major changes occurred in 1877 when Charles O. Newcomb bought the mill and replaced it with a modern facility—considered the best in the county at the time. Also nearby was the sawmill and gristmill John O. Lummis acquired in the 1830s; the former was built before 1789 (perhaps replacing an iron foundry), the latter was built in 1790. [52]

Windmills and steam mills were also popular in South Jersey—for grist and lumber—found primarily in Cape May County and occasionally the Leesburg area of Cumberland County. Cape May was an ideal location for windmills "because of the steady and dependable breezes from the ocean and bay." The earliest one was built for Thomas Press in 1706 on Windmill Island below Town Bank. The last extant example existed in Leesburg in the 1920s (Fig. 77). A variation of the one pictured, most windmills in the county were similar:

They were generally a six-sided building about 20' across the base with sloping sides [of] clapboard...and a moveable six-sided roof on a turntable of wooden rollers. Out from the dormer in one side of the roof extended a long pointed and tapered spindle to which 2" x 10" boards about 15' long were attached to form the sail arms. The cloth sails were fastened by two grids or frames on each side of the sail. These grids consisted of a framework with twelve spindles spaced about 10" apart. The grids were securely bound together, with sails between, and the whole unit was attached to a pole about 15' long which in turn was held on the end of the 2" x 10" board by iron bands. This assembly made the sail arms about 40-45' across. The entire windmill stood about 35' high. [53]

|

| Figure 77. Windmills such as this derelict one in Leesburg provided mill power in Cape May and Cumberland counties. Wettstein, 1920. |

Mill stones were on the second floor of the windmills. Many of the first stones that came from France were made of buhrstone, but by 1850 the cost of importation forced builders to turn to sopus stone from Ulster County, New York. [54]

In 1808 Jesse Springer built a windmill in Goshen. Two years later, Springer built another sawmill in Dias Creek, and in 1820 he built a gristmill for Thomas Gandy Sr. in Seaville. Springer is noted for his experimentation with the design of windmills; one of his designs featured a moveable top. Other windmills were located in Cold Spring, Cedar Swamp, and South Seaville.[55]

While Springer and others were experimenting with windmills in Cape May County, the White Stone Flour-Mill in Salem was working to perfect steam-powered mills. Built by the Salem Steam-Mill and Banking Company prior to 1826, White Stone Mill, was a stone structure five stories tall; its six runs of stone were driven by a large steam engine. The mills regularly dispatched wagons into Delaware and Pennsylvania to pick up grain to be ground into flour, operating until the latter part of the nineteenth century.[56]

By the nineteenth century, mills were common to almost every South Jersey town. According to the Gazetteer of the State of New Jersey, in 1834 Cape May County had eight gristmills and sixteen sawmills, while Cumberland County had forty-four gristmills, twenty-one sawmills, and one each fulling, rolling and slitting mills. Salem County had thirty-three gristmills, nineteen sawmills, and six fulling mills. [57]

Sixteen years later, Kirkbride's New Jersey Business Directory listed nine grist or grain mills in Cumberland County: R.D. Wood and Company, Millville; H. Shaw in Newport; Bateman and Conover, and John O. Lummis, Cedarville; Benjamin Reeve and Daniel Clark, Port Elizabeth; John Trenchard, Fairton; John Holmes, and Mounce and Lot, Bridgeton. Kirkbride also lists twenty-three mill owners in Salem County, five in the NJCHT area: Thomas F. Lambson (steam grist), Clement and Acton (steam saw), and Joseph Petit (grist) in the City of Salem; and J.W. Maskill at Lower Alloways Creek. This last structure is still standing and has been converted into a house.[58]

Cedar Mining

Cedar mining was an early, prominent, but short-lived industry in South Jersey, founded on the white cedar that grew throughout the swamps of Cape May County and in parts of Cumberland, Ocean, Atlantic, and Burlington counties. Here the conditions were ideal for trees to petrify once they died and fell into the muck. The durable and lightweight wood was made into shingles or other objects and used locally or exported to Philadelphia and other Delaware River ports. Much of the cedar came out of swamps in Dennis and Upper townships in Cape May County, and Maurice River and Fairfield townships in Cumberland. White cedar swamps closest to the salt marshes lost their trees to the tidal salt water first. As early as 1868, state geologist G.H. Cook described one Dennisville swamp where hundreds of acres were dotted by stumps and salt grasses overtook the living trees; swamp bottoms were soft and spongy, and here, 11' to 17' below the opaque surface, lay petrified cedar trees:

The peaty soil or muck in which the cedars grew was loose, porous and watery. The roots of the trees extended in all directions near the surface but did not penetrate to the solid earth below. The peaty soil or muck was added to each year by fallen leaves and twigs, and in the cool, shaded, wet swamp the timber buried beneath the surface was for the most part, after hundreds of years, sound and usable. [59]

Cedar mining consisted of removing the fallen trees from beneath the surface of the swamp. Cedar miners had to be skilled so as not to waste time in raising decayed trees that were worthless. Using a 6' to 8' iron rod, the miner probed the swamp for good logs, then he dug through the muck and tangled roots to take a sample of the wood. According to its smell, the miner determined if the tree had blown down or broken off; the former were more desirable because they were usually healthy and sound at the time. The miner then cut away the matted material around the log and sawed off each end. "By the use of levers the log was loosened, upon which it rose and floated to the surface, the bottom side always turning uppermost." [60] Some logs might measure as much as 3' in diameter, and though it appeared as if submerged only a matter of days, it was really several decades.

The log was then sawn into shingle lengths of 18" to 35", which were split into bolts using a froe or froe club; each bolt was then split along the grain to make four shingles, which were dried in the sun before being shaved, or smoothed, using a drawing knife. The size of the shingles ranged from 18" x 6" x 1-1/2" to 36" x 7-1/2" x 1-1/2". The average life span of such a shingle on a building is seventy to eighty years. [61]

In addition to shingles, the early settlers also used cedar for their fences, houses, farm buildings, canoes, staves, and cordwood. Future generations employed it in the manufacture of floors, rafters, joists, and doors as well as tanks, churns, firkins, pails, washtubs, paving blocks, siding, lath, crates, and furniture. In 1856, rails sold for $80.00 to $100.00 per 1,000, while in 1880 shingles brought $22.00 per 1,000.[62]

Like ship builders, cedar miners needed other skilled craftsmen in the community to supply them with tools. They made their own wood tools and handles, but relied on local smithies to forge iron axes, blocks, butters, crosscut saws, drags, drawing knives, levers, progues, froes, jointers, spades, and shaving horses; steel saw blades were also purchased. [63]

By the early twentieth century, the last of the shingle makers were gone and with them went a traditional skill. In 1937 the South Jersey Peat Company resurrected, however, the practice of extracting the cedar logs. The company relied upon modern tools to bring up logs from the Yock Wock Swamp below Mauricetown. Wire cables were looped around them and a power-driven windlass pulled them out of the muck. The logs were then sent to a sawmill to be machine cut into siding for boats, shingles, and box material. [64]

Lumbering operations such as this continued until the 1950s, with logs transported via wood sled and hauled from the swamp by a gasoline-powered tractor. Poles and boughs were laid across the trail in the softer places in an effort to keep tractors from sinking into the marsh. Upon reaching solid ground the logs were loaded onto a truck and taken to a sawmill. Lumbering operations have virtually ceased today because of changing technology and a decreasing supply of white cedar trees.[65]

Sandmining

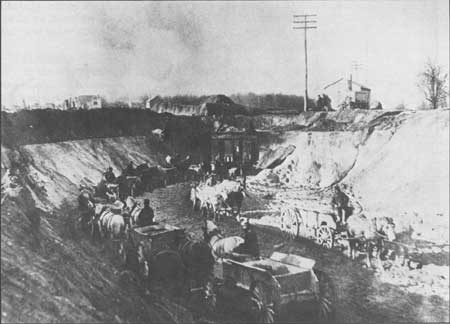

Sandmining has been and continues to be a prominent industry in South Jersey. Beginning in the eighteenth century, the area's sand was well known for it fine-grained consistency, which was ideal for making glass. "It was the presence of this type of sand in South Jersey that brought the first glass-manufacturing plant into the county. . . ." [66] Although some sandmining took place in Salem and Cape May counties, most occurred—and continues to—in Cumberland County around Millville (Fig. 78-79), Dividing Creek, Cedarville, Manumuskin, Dorchester, and Vineland.

|

| Figure 78. South Jersey sand, here horse and wagon has played an important role in South Jersey glass manufacturing since the late 18th century. Wettstein, ca. 1900. |

|

| Figure 79. Sand "pitts," or sand mines, such as this one operated by Samuel Hilliard, are still found in Cumberland County in the Maurice River area. Atlas, 1876. |

Perhaps one of the most prominent sandmining companies was the Crystal Sand Company in Cedarville. Captain Henry S. Garrison, an inventor of sand-related machinery and a promotor and manager of sand properties, began his career as a sand digger for his father in Salem County. Later Garrison purchased land in Cedarville and organized the Garrison Sand Company. As glass interests increased in Bridgeton so did the need for another sandmine. Garrison merged with the Crystal Sand Company and soon had branches on the Maurice River and in Vineland. [67] Crystal Sand closed in 1917.

The Bridgeton Dollar Weekly in 1886 explained the procedures used by Garrison to mine sand. If no problems were encountered in a sand pit, then the workers would begin digging by hand. Once the sand was excavated, the load was transported to the wash house and emptied into a cleaning trough, where it was washed by water piped in by a ten-horse power steam engine. The sand was then sifted and rewashed to separate it from soluble loam. The sand was washed twice more, then carried upward via elevators and dumped into railroad cars. Up to 50 tons of sand could be washed daily with this procedure. [68] Problems occurred, however, if a natural stream was hit and the pit filed with water. To continue working, the workers had to drain the pit by digging a ditch, one of which was approximately 1,500' long and 32' wide.

The Cape May Sand Plant operated on Sunset Boulevard at the entrance to Cape May Point for many years until closing in the 1920s. The company, run by George and Betty Patinee, was noted for uncontaminated sand whose grains were uniform in size. Workers dug the sand offshore, hauled it away for delivery, then awaited the next tide to replenish their supply. In 1941 Harbison-Walker Refractories, a division of Dresser Industries, built a Magnesite Plant on part of the old sand-plant property. Here magnesite, which is used to make fire bricks, was extracted from the sea water. The plant closed in 1983. [69]

Several sandmining companies continue to operate in southern Cumberland County, including the Morie Company in Mauricetown, Ricci Brothers Sandmining Company near Port Norris, and WHIBCO Inc. in Leesburg. Today, however, much of the industry relies on new technology, computers that can measure grains as small as 0.0021 mm. The sand also becomes an ingredient for products other than glass: microprocessors, oven ware, roofing gravel, and water filters. [70]

Commerce

In the nineteenth century, South Jersey towns were home to a range of businesses and professionals; even small villages had the requisite general store (Fig. 80), as well as physicians, hotels, dry goods merchants, blacksmiths, confectioners, carpenters, wheelwrights, boot makers and sellers, cabinet makers, carriage makers, tailors, weavers, tanners, and bricklayers. The Bridgeton and Salem Directory (1877), for instance, reports that Dividing Creek had a physician, butcher, livery stable, wheelwright, two blacksmiths, two carpenters, and three stores; Dorchester had a physician, blacksmith, confectionery, and three stores. [71] According to Boyd's Directory (1899-1900), Hancock's Bridge advertised two lumber firms, a poultry and cattle dealer, three carpenters, two canneries, a plasterer and contractor, flour mill and gristmill, meat market, and blacksmith (Fig. 81). [72]

|

| Figure 80. During the 19th century almost every town in South Jersey had general stores such as this one in Millville. Wettstein, late 19th century. |

|

| Figure 81. Peterson's Black Smith shop in Millville made horse shoes and axes. Wettstein, ca. 1900. |

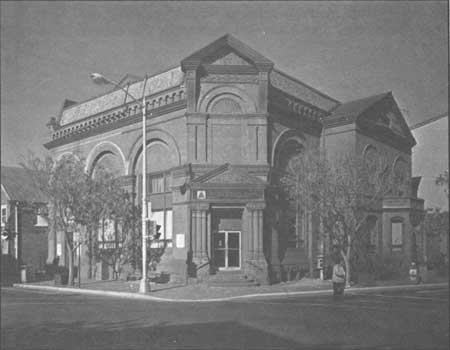

One of the most elegant commercial buildings in Bridgeton is the Cumberland National Bank, built in 1886 at Laurel and Commerce streets (Fig. 82) by the design team Hazelhurst & Huckel. Architects Edward P. Hazelhurst (1853-1915) and Samuel W. Huckel Jr. (1858-1917) designed a plethora of buildings—especially in the New Jersey-Philadelphia area—from 1881 until 1900, after which they practiced separately. Hazelhurst had worked in the Philadelphia offices of Frank Furness and T.P. Chandler, and he went on to design a range of institutional building types as well as numerous houses. Huckel is credited with the pair's church designs; his award of the commission to remodel New York's Grand Central Station in 1900 ended the partnership. [73]

|

| Figure 82. Hazelhurst & Huckel of Philadelphia designed the present Cumberland National Bank building, erected in 1886. |

The Industrial Directory of New Jersey (1909) touted many possibilities for South Jersey's small towns. Dorchester, with excellent railroad service, was an ideal site for manufacturing because goods could be shipped by land or water. The town also offered a public school, high school, and a Methodist Episcopal church. Similarly, Green Creek in Cape May County was suitable for a cannery of vegetables, oysters, or clams. The Atlantic City and West Jersey Railroad was two-and-one half miles from town and the land was relatively inexpensive; a school, two churches, and a labor supply were already in place. [74]

Developed towns such as Quinton boasted two canneries and a glassworks on Alloways Creek, which afforded easy shipping. Moreover, there was a local building and loan association with 100 stockholders and assets of $38,604, two schools, and two churches. "The town, considering its size, is a manufacturing place of some importance, and the people would be pleased to have these interests extended, particularly in the direction of industries employing female labor." [75]

Many towns such as this lost their appeal as manufacturing centers after the railroad was closed in the mid twentieth century; modern industrial facilities were then built closer to New York and Philadelphia. The exception is Millville, which continues to support two glass makers: Foster Forbes, a division of American Glass, and Wheaton Industries. Today, some residents work for the Salem Nuclear Power Plant, South Jersey Gas Company, Atlantic City Electric, and New Jersey Bell, as well as the state government, South Jersey Hospital System, and DuPont Inc. at Carney's Point. Farming—dairy and truck—sustains Cumberland and Salem county residents. Additional work is found at the Millville and Cape May airports, seaside resorts, sandmining companies, and other concerns.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

new-jersey/historic-themes-resources/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 14-Mar-2005