|

National Park Service

Historic Themes and Resources within the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail Route Southern New Jersey and the Delaware Bay: Cape May, Cumberland, and Salem Counties |

|

CHAPTER 6:

TRANSPORTATION

South Jersey, in step with nationwide innovations in transportation, progressed from depending upon trail, sail, and rail for travel and economic development from the seventeenth through the twentieth centuries. Today, only the footprint and a smattering of structures remain from burgeoning port towns and railway hubs. The major—and most intact—network is the state and county highway system which, for the most part, mirrors the historic trails and roads that bisected the region.

Indian Trails

Many of the thoroughfares employed by seventeenth-century European settlers and inhabitants of subsequent seaside, domestic, and commercial centers were taken from the Lenape Indians. They established an extensive network of trails in both North and South Jersey to facilitate seasonal migrations to the coast; trails also enabled improved trade relations, attendance at ceremonies held at major villages, and the seasonal movement of hunting grounds. All major trails linked villages, while a network of minor trails that branched out from them led to hunting and fishing grounds, camp sites, gardens, and rock shelters. [1]

The nature of these Indian paths benefitted the Europeans immensely by not only linking major settlements, but by mapping out the courses of least resistance to the pedestrian traveler. Logic dictated that Indian trails—2' to 3' across—were kept clear by regular travel and were situated along dry land in relatively low terrain where there was an absence of rocks and other obstacles. When crossing streams, Indians chose areas that were shallow, of uniform depth, and with firm bottoms. In addition to traveling on land, the Lenni Lenape made great use of the dense network of inland and coastal waterways via dugout canoes of tulip popular, white cedar or sycamore, or a bark canoe of elm, black oak, or hickory bark. [2]

Upon arrival in North Jersey and New York, the Dutch used Indian trails as trade routes, establishing along them trading posts and forts, such as Fort Nassau near the present town of Gloucester, and Fort Casimer near New Castle, Delaware. Many such centers existed along the banks of the Delaware River. If the Indians were at war, traders traveled in sloops up the waterways instead of risking capture on their trails. [3]

When the Swedes arrived in the Delaware Valley, they brought with them economic competition. Like the Dutch, they adopted the Indians' routes and established the forts and trading posts along the river. Fort Christina was established on Christina Creek in Delaware, and Fort Elfsborg was erected on the Delaware River just below Salem Creek. [4] As the population grew and migrated toward the interior, Indian trails again led the way.

Roads/Turnpikes

Travelers' reliance on water for mobility was one result of the crude condition of overland routes. Most trails were wide enough only for one person on foot or horseback; if they were passable for wagons, an average rainfall could transform the route into dense mud where wagons were easily mired. These conditions persisted even as more formal turnpikes were built. The early farmers attempted to overcome them by attaching sleds on runners for hauling grain, hay, and tobacco—but the rivers continued to prove most efficient. [5]

By the end of the 1600s, the colonial government recognized the need for improved roads. In 1681 the Assembly authorized a survey for the King's Highway from Burlington to Salem. Four years later, the West Jersey Assembly implemented the last measures for creating a highway system to connect the Salem area with the upper part of the West Jersey province. Through passage of general legislation, the Assembly "provided locally for the laying out of highways while the inhabitants were empowered to levy such taxes as shall be necessary from time to time, for the making and repairing their respective bridges and highways." [6]

By 1697 the West Jersey Assembly agreed that a highway was needed to connect Cape May with the capital, Burlington, with the hope that citizens might become more politically active. The burden of cost and maintenance fell on Cape May inhabitants until the area between Burlington and Cape May could be settled; the highway was completed in 1707.

In 1760 the Assembly decided that the best way to improve overland passage was to make road-building officials responsible to the people. As a result, overseers and surveyors were elected by voters—and were punished if they neglected the duty. Overseers inspected the roads and bridges in a respective district, and if repairs were needed, he called on the residents to make them. The fact the government did not concern itself with roads and their maintenance allowed citizens the right to build their own thoroughfares for personal or public interest. Many of the highways in South Jersey were developed for the purpose of exploiting agriculture and natural resources, especially to bring timber and iron ore out of the interior. Other roads were established to serve area glassworks. [7]

Residents gradually transformed the winding trails by cutting back trees and brush. They were often ungraded and stumps were a menace, and the road sometimes followed an awkward course to avoid bisecting a farmer's field. Neither were swamps generally traversable, since the road through them consisted of a few loads of unbroken stone or a series of logs laid crosswise to form a corduroy "pavement." Both proved problematic well into the nineteenth century. [8]

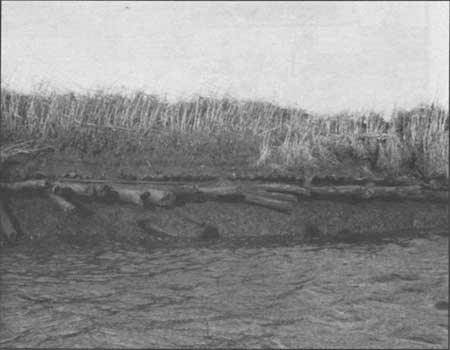

Traces of these old corduroy roads can be found along the banks of many of the creeks in South Jersey. Definite remains, however, can be found along the banks of Dennis and Sluice creeks in Cape May County (Fig. 83). Many of the logs, branches, twigs and bark used to form the roadbed lie perpendicular to the creeks within their banks. In many instances, the logs protrude from the shore in several layers. New logs were continuously placed atop the old bed because the combination of soft ground and weighty wagons caused them to sink into the mud. If the logs were not replaced, wagons would become mired and movement impossible. In most cases the timber used to make the roads was harvested from nearby cedar and pine forests.

|

| Figure 83. Corduroy road remains, such as these along Dennis Creek, are found preserved but buried in layers of mud throughout the tidal marshes. Sebold. |

Bridge construction, like road development, was directed by local officials. The expense, however, warranted municipal or county financial assistance. Usually of timber construction with planks laid as flooring, bridge surfaces also had to be repaired or replaced often. Stone bridges were rare because of the high cost of construction. Some of the earliest bridges in Salem County were located at Hancock's Bridge in Lower Alloways Creek Township and Quinton's Bridge in Quinton Township. Both were the site of Revolutionary War battles.

In 1711, Benjamin Acton, a surveyor for Salem County, helped to lay out the Old Penn's Neck Road which ran from Market Street in Salem across the Salem Creek via the Trap Causeway and Bridge, in Mannington Township, and then on to Penn's Neck. A century later, much of this road and its bridge were abandoned when the New Street (presently Griffith Street) Bridge was constructed. By the time New Street was finished, most of the main roads in Salem County had been laid out. In 1820 John Denn commenced building a canal near Salem in Mannington Township in order to shorten navigation on the Salem River by two miles. The one-half mile canal was completed in 1840. [9]

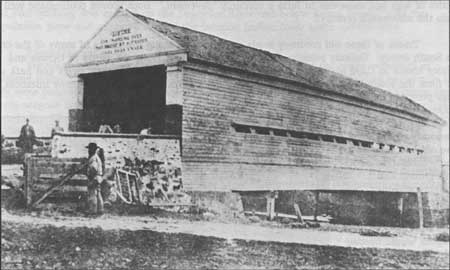

Among the earlier crossings in Cumberland County was a bridge over the Cohansey River at Bridgeton. When Bridgeton first appeared as a small settlement in the early eighteenth century, it was known as Cohansey or Cohansey's Bridge. The exact date of the first bridge's construction is unknown; however, in a reference concerning the building of John Garrison's house in 1715, there was mention of it relative to the bridge. The bridge at Cohansey was part of the road that connected Salem with Cape May via Greenwich and Buckshutem. [10] Numerous such covered bridges existed throughout the area, including one across Dividing Creek (Fig. 84).

|

| Figure 84. The covered bridge across Dividing Creek carried modern Route 553; historically passengers were warned of $10 fines for moving "faster than a walk." Wettstein, late 19th century. |

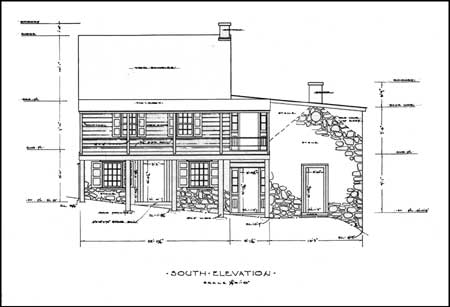

By the end of the colonial period, the main roads in South Jersey were in place. The most important of these, the King's Highway, connected Salem with Burlington to the north and with Greenwich via Quinton's Bridge and Jericho. From Greenwich it went on to become Broad Street in Bridgeton. Once Commerce Street Bridge was erected in Bridgeton in 1771, the highway turned southeast toward Cape May. Before this, the road turned northeast at Pearl Street, to the present-day corner of East and Irving avenues, toward Indian Fields. [11] Another road paralleled the Delaware Bay shoreline from Salem to Bridgeton, though its exact route remains a mystery. In the mid eighteenth century, a road from Port Elizabeth to Shingle Landing (later Millville) on the east side of Maurice River was laid out from Berriman's Branch near Leaming's Mill. At that point a bridge on log cribs was built across the river. In 1798, another road was made from Bridgeton to Fairton; prior to it, travelers reached Greenwich via the King's Highway and Laning's Wharf ferry. In the early 1800s, Bridgeton's East Commerce Street continued on toward Millville, while Buckshutem Road branched off from it to link up with the Spring Garden Ferry on the Maurice River; the road continued along the east side of the river into Port Elizabeth. [12] The Ferry Tavern is extant in Greenwich (Fig. 85).

|

| Figure 85. Greenwich Ferry Tavern-Jail (1686, l760, HABS No. NJ-268). Built by Mark Reeve in 1686, the one-story block was probably the jail when Greenwich was the Cumberland County seat after 1748. |

Many of the early roads in South Jersey can be identified by the presence of a tavern or inn. Once the roads were established, stagecoaches became a common mode of travel from Powles Hook and Cooper's Ferry to New York and Philadelphia. It was not until after 1750 that stagecoaches were used for local traffic. [13] Between 1765 and 1775, the Cooper's Ferry stage line was extended east and south to connect Philadelphia with South Jersey. The first line to open ran between Cooper's Ferry and Salem once a week, then every five days. The subsequent line linked Cooper's Ferry to Bridgeton, with branches to Greenwich and Cape May. In 1773, another stage line was opened from Cooper's Ferry to Roadstown. In 1815, a stage line served the route from Millville to Philadelphia via Malaga. [14]

Properly financed turnpikes of stone or gravel were demanded to accommodate nineteenth-century traffic as the population rose and the frontier line advanced to link up with the rest of the East Coast. Moreover, an improved road reduced the transportation cost of shipping products to Philadelphia and New York markets. In 1825, a direct road from Bridgeton to Shiloh was laid out and later became part of the toll-road system to Salem. Some important turnpikes were built in South Jersey between 1849 and 1860: the Bridgeton and Fairfield, Bridgeton and Millville, Cape May, Millville and Malaga, Port Elizabeth and Millville, and Salem and Woodstown. The turnpikes in South Jersey suffered from low capitalization and mileage, such that companies found it difficult to attract outside investors. So they relied on local farmers, storekeepers, merchants, and stage drivers—"the value of whose property or business would increase with better transportation facilities." Even with financial backing, many companies lacked the money to maintain the roads. [15]

The toll revenue collected for using the turnpike was determined by each company's incorporation charter; rates were inconsistent, based on the route's cost of construction and volume of traffic. The average rates consisted of the following: carriages with four horses or less cost 1 cent per mile; a horse and rider cost 2 cents per mile; a dozen calves, sheep or hogs cost 1/2 cent per mile; and a dozen cattle, mules, or horses cost 1 cent per mile. [16] Collectors lived in toll houses that were built five to ten miles apart. Deerfield Pike Toll Gate House, outside but near the NJCHT boundary, was built in 1853. [17] In 1876 there was a toll gate in Quinton's Bridge.

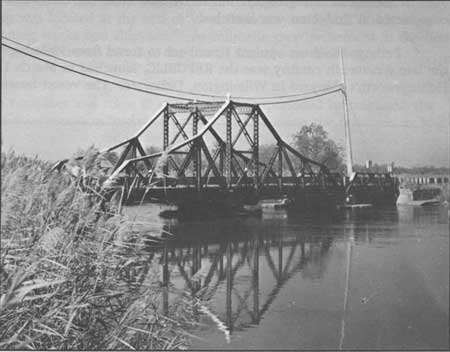

By the last quarter of the nineteenth century, several substantial bridges helped facilitate travel throughout the network of small South Jersey towns. Mauricetown had a 60' drawbridge that carried High Street across the river; this was replaced in 1888 by a single or double intersection plank-deck Pratt bridge that remains partially extant. Among others were a drawbridge at Quinton's Bridge, and an undisclosed type at Hancock's Bridge. An existing nineteenth-century bridge can be found on New Bridge Road in Lower Alloway's Creek Township, Salem County (Fig. 86).

|

| Figure 86. New Bridge Road Alloways Creek Bridge, built by the New Jersey Bridge Company of Manasquan (1905), is an unusual metal truss swing bridge with a Pratt pony-truss approach. |

Whether plank or macadamized, turnpikes offered definite benefits to local farmers and industries despite their cost: smoother and speedier travel, fewer delays, and the potential for larger loads. The revenue came mostly from teamsters who hauled freight in wagons, or herds of animals being driven to market. Most turnpikes, however, especially those in sparsely settled areas, were unprofitable and met their demise once the railroad was established. [18]

Steamboat

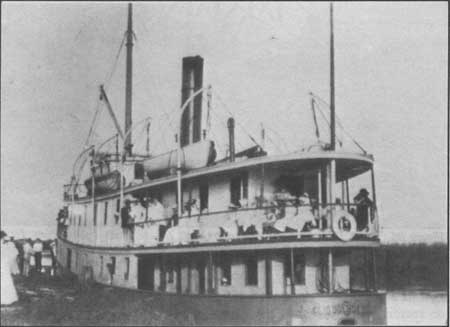

Steamboats replaced schooners as the main mode of transportation for persons traveling from Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Wilmington to Cape May for a vacation in the spring and summer during the early nineteenth century (Fig. 87). Even before the railroad, steamers competed with turnpikes, though predominantly for passenger rather than freight services. As early as 1816, the steamboat BALTIMORE traveled between Salem and Philadelphia twice a week; once in Salem, passengers continued to Bridgeton and Cape May via stagecoach. By the 1830s there was a great demand for steamboat travel on the Delaware River, and rate wars were common. [19]

|

| Figure 87. Steamship CLIO, of Odessa, Delaware. New Jersey: Life, ca. 1900. |

With Cape May's ascension as a summer resort, steamboat service was extended to the southern tip of New Jersey. In 1824 the DELAWARE, under command of Captain Whilldin, began shuttling vacationers from Wilmington and New Castle, Delaware, and Philadelphia to the shore. As the demand for this service increased, established and new independent lines competed for riders, and the ticket price fell from $5 to 50 cents. By mid century, tourists and goods were imported from New York along the Atlantic coast. [20] Few steamboats were built in the South Jersey region, but in October 1856 the first steam-powered vessel constructed in Bridgeton was launched. [21]

Perhaps the most opulent steamboat to travel from Philadelphia to Cape May during the late nineteenth century was the REPUBLIC, launched in March 1878 from Harlan and Hollingsworth's shipyard in Wilmington, Delaware. The vessel boasted large, fully furnished saloons, sixteen state rooms, and two private parlors on the upper deck. It accommodated 2,500 passengers in luxury—which included breakfast, lunch, and dinner. A similar ship, the JOHN A. WARNER, bore its passengers from Philadelphia and Wilmington to the now-lost resort of Sea Breeze. [22]

Considerably inland from bay waters, Bridgeton sought steamboat line in 1844, and the following year the COHANSEY began making thrice-weekly excursions from Bridgeton to Philadelphia, with stops at Greenwich, Port Penn, Delaware City, New Castle, Marcus Hook, and Chester, as well as occasional trips to Cape May. Three other steamboats operated on the Cohansey: the ARWAMES, PATUXENT, and EXPRESS. [23] In 1876, Bridgeton's steamer landing was on the east shore of the Cohansey River between the Jefferson Street bridge and a glassworks. [24]

The Maurice River Steamboat Company operated the THOMAS SALMOND which, like the Cohansey River steamers, offered excursions from its home port to Philadelphia. Before steamers reached this far up the Cohansey and Maurice rivers, stages via turnpikes carried travelers from Bridgeton and other interior towns to Salem to pick up the steamboat. [25] Salem's steamboat landing was located at the end of West Broadway at Salem Creek, where it shared a dock with a canning works and shipyard. [26] As railroads grew prominent in the South Jersey region during the late nineteenth century, the use of steamboats declined.

Railroad

By the 1860s, the turnpikes and stage lines were being superseded by railroads, the most economical mode of transportation to date (Fig. 88). Establishing the railroads in South Jersey took a long time but showed a gradual profit. The first, the Camden and Woodbury Railroad, was chartered in 1836, and received immediate support from the residents of Woodbury who sought a quick route to Philadelphia. Its charter called for the line to eventually extend to Cape May but it failed first due to lack of ridership. The Camden and Woodbury failure did not discourage proponents of a line connecting South Jersey with Philadelphia—including Salem and Bridgeton residents. In 1853 the Camden-to-Cape May line became a reality with the West Jersey Railroad, authorized to build a line from Camden through the counties Gloucester, Salem, Cumberland, and Cape May. The railroad began operation in 1857. By the end of the nineteenth century, the West Jersey Railroad offered services to Philadelphia via Salem, Swedesboro, Woodbury, Wenonah, Glassboro, Clayton, Vineland, Millville, and Cape May. [27]

|

| Figure 88. "Map of Rail Roads of New Jersey, (1871)." The railroad introduced great industrial changes: In South Jersey, produce and shellfish were shipped to market faster, and glass with less breakage. |

The same year the West Jersey Railroad began operation, the Millville and Glassboro Railroad was incorporated with a twenty-two mile route from Millville to Glassboro. At Glassboro, passengers could take a stagecoach to Woodbury. In 1875 the West Jersey Railroad connected with the Millville-Glassboro Railroad in Glassboro, and passengers could then complete their trips to Camden and Philadelphia without interruption. [28]

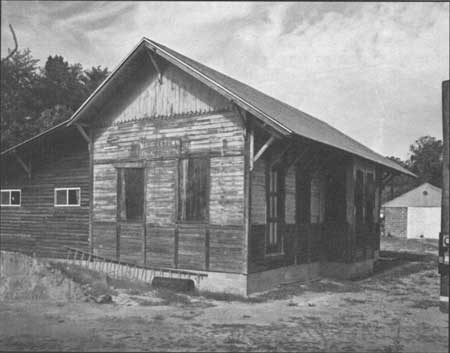

The Cape May and Millville Railroad Company was incorporated in 1863 as a competitor to the Millville and Glassboro Railroad; the Cape May and Millville line acquired permission from the state to build along the right-of-way that the Millville and Glassboro line had reserved in a previous charter. The state, however, favored the Cape May and Millville company because it had agreed with the West Jersey Railroad to serve as one rail system that connected directly with the Salem Railroad Company. This single network could then be "operated with greater economy under one management." West Jersey could lease and operate the Cape May and Millville Railroad and the Salem Railroad; this passed through Manumuskin, Belleplain, Woodbine, Mt. Pleasant, Seaville, Swainton, Cape May, Court House, Rio Grande, and Bennett. [29] The railroad tracks in Millville ran northwest to southeast through the town with a depot at High and Broad streets (Fig. 89). Another minor depot was located at the "rear of the yard of Warren Hall on the north side of Broad Street between Buck and High [streets]." [30]

|

| Figure 89. Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore Railroad Millville Station (ca. 1879). This depot with deep, braced eaves and large windows was at Broad and High streets. Wettstein, 1958. |

In 1861, the Pennsylvania Railroad laid the first rail lines into Bridgeton. The railroad had a terminal on Irving Avenue near Walnut Street, and later extended around East Lake and downtown to what is now the visitors' center. [31] In 1875 the West Jersey also extended a line to Bridgeton via Glassboro and Elmer; at Elmer a connection could be made with the Salem Railroad. The line that connected with Bridgeton eventually ran a spur to Port Norris; this was called the Bridgeton and Port Norris Railroad and was incorporated in 1866. Completed in 1875, it transported oysters from Port Norris to Bridgeton and on to major market cities. Shortly after completion the railroad was sold to the Cumberland and Maurice Railroad Company in foreclosure proceedings. The line served Bridgeton, Buckville, Fairton, Westcott's, North Cedarville, Cedarville, Newport, Dividing Creek, Buckshutem, Mauricetown, Centreville and Port Norris. Stage connections could be made at Newport, Dividing Creek, and Mauricetown (Fig. 90), while the train connection to Philadelphia could be made at the West Jersey depot in Bridgeton. [32]

|

| Figure 90. Cumberland & Maurice Railroad Co. Mauricetown Freight Station (late 19th century). Small with decorative Victorian "framing," this depot has been moved to Route 47. |

The New Jersey Southern Railroad, a unit of the New Jersey Central Railroad, was incorporated in 1867 and ready for service from Vineland in 1872. The line passed through the central part of Cumberland County extending from Bayside/Caviar on the Delaware River to Bridgeton and Vineland, then northward to New York City. In the 1880s the railroad passed under the control of the Reading Railroad company. [33]

The Salem Railroad, chartered in 1856, was originally sixteen miles long from Salem to Elmer. The line could run "from a point in the town of Salem, or within one mile thereof, to any point on the West Jersey Railroad, at Woodbury or south thereof, which the directors deem most eligible." [34] It was completed in 1870, including a spur to Bridgeton. The Salem depot for the West Jersey and Seashore Railroad was located on Grant Street. Built in 1888, the building had separate areas for women and smokers, as well as passengers and baggage. The depot was active until the 1920s and was demolished in 1944. A freight-train station and office was also located on Grant Street. Today the latter continues to be used as the office for the West Jersey Line Excursion Tours, which offers recreational train rides through Salem County. [35]

By the 1930s, the railroad's importance in South Jersey started to diminish. Businesses and vacationers, as well as residents, relied more upon vehicular transportation. In addition, many of the industries that had once supported the railroad were no longer profitable; the caviar industry had ceased and the oyster industry was slipping into a forty-year slump that continues today. In 1933, the Maurice River Branch of the Pennsylvania Railroad had reached such a low ebb that the New Jersey State Public Utilities Commission approved a plan to eliminate the service. [36]

In the mid twentieth century, Conrail took over several of the financially failing lines that passed through South Jersey. One, the Millville-Leesburg and Manumuskin line, was rehabilitated in 1982 to ship sand for the local sandmining companies. The same year, however, Conrail dropped its service to Seabrook—just north of Bridgeton—due to dwindling profits. [37] Four years later Conrail also dropped its southern railroads, which included the Millville-Leesburg and Manumuskin and the Bridgeton-Mauricetown lines. The Winchester and Western Railroad bought forty-six miles and operated eighteen miles of Conrail's lines. "Along with the Bridgeton to Millville run, Winchester and Western also operates two other freight trains around the county, forming a horseshoe route around townships that include Dorchester, Downe, Commercial, Lawrence, Fairfield and Upper Deerfield." [38]

Electric Trolley

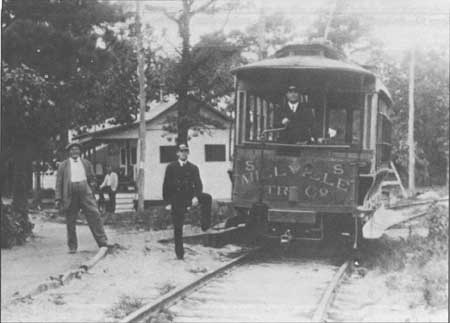

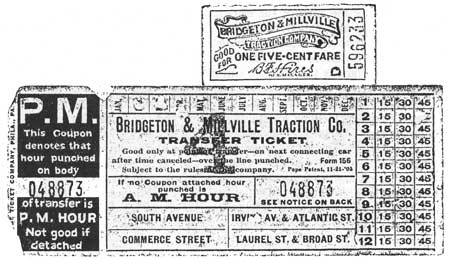

Prior to the turn of the century, the electric trolley developed as a popular mode of transportation, particularly in Cumberland County. As early as 1893, the Bridgeton and Port Norris Railway Company was organized with both a freight and passenger service. The line started in Bridgeton and continued on to Fairton, Cedarville, Newport, Dividing Creek, Port Norris and Bivalve. Substations supplied the current between cities; the one between Cedarville and Bivalve was in Dividing Creek. The 5-cents ticket price of the Bridgeton and Port Norris Railway Company route was affordable for everybody, including many of the workers who came from Philadelphia for spring planting and fall harvesting seasons. [39] By 1900, the Bridgeton and Port Norris Railway Company had merged with the Bridgeton and Millville Traction Company (Figs. 91-92). As a result, the Bridgeton and Port Norris route became one of three lines operated by the Bridgeton and Millville Traction Company. The second was the Bridgeton and Millville line, which left from Bridgeton and arrived at the Pennsylvania Railroad station in Millville. The third was a local line that served only Bridgeton. In 1922, the Bridgeton and Millville Traction Company ceased operations due to delinquent taxes, and the rail lines were removed. [40]

|

| Figure 91. The Bridgeton & Co. trolley, shown here at the Union Lake Park stop, provided transportation to Cumberland County residents from ca. 1900-22 Wettstein, early 20th century. |

|

| Figure 92. Bridgeville & Millville Traction Co. trolley tickets. Gehring. |

The trolley was prominent throughout all resort towns, and Cape May Point was no exception. The Cape May Delaware Bay and Sewell's Point Railroad carried riders from Cape May Point through Cape May to the Sewell's Point amusement complex. When the line first opened cars were pulled by horses; they were later converted to steam, and finally to electricity. The electric cars served the Cape May and Sewell's Point area until 14 October 1916 when the company closed due to the rise in automobile traffic. [41]

As the trolleys in Cape May and Cumberland counties decreased in importance, they were increasingly used in Salem County. The Salem-Penns Grove Traction Company began its service in 1917, with a line from Salem through Pennsville and on to Carney's Point. Until 1927, all passengers had to dismount the cars and walk across the Penns Neck Bridge, as it could not withstand the weight of the cars. In 1927 a more durable bridge was erected and it remains in place today. The trolley service ceased in 1932, again due to the increasing use of cars; moreover the maintenance and repair of cars and track had become too costly. Today, the only evidence of the extensive South Jersey trolley system is one structure, a garage in Pennsville at Broadway and Union streets. The garage appears the same as when it was used by the traction company, except that the hinged front doors have been replaced. [42]

Modern Highways

Despite the accessibility of trolley and rail transportation, roads were increasingly utilized by travelers, farmers, and laborers. In the late 1870s, the New Jersey Board of Agriculture was prompted to complain about the road systems, whose overseers inadequately maintained them; its constituency, the farmers, were most annoyed as it was their tax dollars intended for the upkeep. In 1891 the Legislature abolished the use of overseers, and road maintenance hence became the responsibility of a township committee that issued bonds to finance road construction. [43] The same year, another law passed providing state aid for the construction of permanent, improved roads, and by 1894, fifty miles of stone roads had already been laid in New Jersey and the first Department of Public Roads was established; six years later, the position of State Supervisor of Roads was created. [44] Furthermore, with the establishment of a prison in Leesburg in 1913, and one existing in Trenton since the nineteenth century, the state easily employed convicts to maintain the roads, as well as quarry materials for building purposes (Fig. 93). [45]

|

| Figure 93. Working on the roadbed in Millville, Main Street/Route 49 at Fifth Street. Wettstein, 1915. |

Today, four state highways make traveling through South Jersey a simpler task. These include Route 49, which runs east/west, and Routes 47, 9, and the Garden State Parkway, which all run north/south. With the exception of the Garden State Parkway, which was constructed in 1953, the other highways follow very close to the original roads cut through South Jersey. Route 9 is considered the oldest road to parallel the Atlantic Coast from Cape May to New York, while Route 47 was one of the first roads that led from Camden to Cape May. The Route 49 corridor from Salem to Jericho appears to have been part of the original King's Highway that was set up in the eighteenth century. Moreover, the portion of this highway that leads from Bridgeton to Millville is part of the original road laid out in the 1800s.

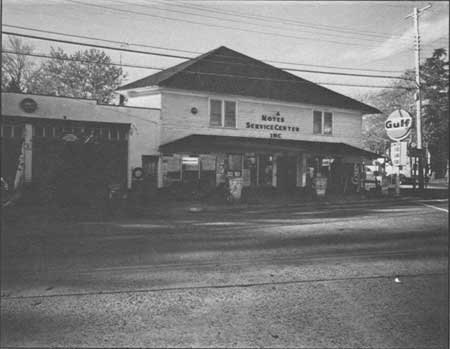

In the early twentieth century, roadside architecture diversified to include a range of automobile-related services: tourist cabins, diners, roadside fruit/vegetable stands, and most important, filling stations. The stations in South Jersey are found mostly along major thoroughfares such as Routes 47 and 49. One of the earliest types is the curbside filling station of the 1920s, where pumps were located "along streets in front of grocery, hardware and other stores which, carrying household petroleum products, had expanded into gasoline sales." [46] Along Route 49 in Shiloh two such filling stations are extant. One is Richardson's General Store, at the intersection of East Avenue; the second is Noyes Service Center at the corner of Route 696 (Fig. 94).

|

| Figure 94. Noyes [Gulf] Service Station (ca. 1940). This typical rural station is shared with a general store and other roadside businesses; the storefront, gas pumps and service bay are modern. |

The later house and house-with-bay station types of the 1920-30s are represented by sites along Route 49 near Dennisville, and on Main Street in Port Norris. The house/office, topped with a gable or hip roof and set behind the pumps, was designed to blend with the local neighborhood. A smaller but more formal example is found in a building relocated to Mauricetown, which the owner believes was a Sunoco station. This small, frame, house type features fifteen-light windows flanking a central door; the roof features molded blue "shingles" and a central eyebrow profile. Today it is used as the Pump House Antiques shop.

An oblong box most accurately describes the service stations built during the Depression, when oil companies used a flat roof and incorporated the service bay into an enlarged office to reduce construction costs. A growing line of automotive supplies occupied the windows to attract customers. This type of station was built as late as the 1960s with some alterations, such as using gable roofs to give the building a quainter colonial look. Many of these station types survive in Salem, Bridgeton, and Millville. [47] Over the years, many early filling/service stations have been preserved by their adaptation to new uses, such as stores or dwellings, while others are empty and derelict.

In tandem with the advent of filling stations are facilities for food and shelter: diners and tourist cabins. The Salem Oak Diner (ca. 1940s, Fig. 95), at East Broadway, is a classic rectangular steel diner, inside featuring counter and booths where patrons enjoyed hearty, convenient and inexpensive food. The few historic lodgings that exist are not surprisingly located at the southerly end of Route 47 as it approaches Cape May. Adjacent to the road, these clusters of small cabins with a central office provided inexpensive lodgings for travelers who were not dependent on public or mass transportation. One or two examples of these early twentieth-century properties remain in place today, though they have been moved, considerably altered, and appear run down.

|

| Figure 95. Salem Oak Diner (ca. 1940s). This classic glass and steel roadside eatery features an especially noteworthy neon oak leaf in its signage. |

For the traveler who sought the maximum flexibility in automobiling, early recreational vehicles such as this mobile home dubbed "Home Comfort" made excursions to shore resorts such as Sea Isle City as expensive as the gasoline needed to get there (Fig. 96).

|

| Figure 96. Motor homes such as this, owned by Wally Hiles of Millville, were an alternative to motels at many Atlantic resorts. Wettstein, early 20th century. |

Air

The twentieth-century transportation breakthrough of air travel is evidenced on a small but significant scale in South Jersey. In 1940-41, the U.S. Army built the Millville Army Airfield as a defense facility where pilots of P-47 thunderbolts trained; the base is closed, but the representatives of the resident Millville Army Airfield Museum consider it the first designated defense airport. The site (Fig. 97) included standardized barracks, offices, mess hall, movie theater, fire station, and aircraft facilities. Some modern industrial buildings share the old airfield today, as part of the city's industrial park is there.

|

| Figure 97. Millville Army Airfield, built 1941-42. As seen today, the complex of narrow, one-story concrete-block barracks are plain; hangars of corrugated metal are still used. Wettstein, 1990. |

|

| Figure 98. The mosquito was the logo of the World War II airbase as a banded fighter plane. |

The base operated until the end of the war, when the barracks were converted into apartments for veterans and their families. Eventually these structures were let to non-veterans, and after that used as offices. In 1946, after the City of Millville inherited what became a small, regional airport, Francis Hine and Josiah Thompson set up the Airwork Corporation in several of the extant buildings. The business, which dealt with overhauling airplane engines as well as the sale of parts, spurred the arrival of a handful of other small firms that continue to sustain the airfield. [48] The former base is celebrated today by the museum, which has appropriated the base's tongue-in-cheek symbol, the virulent mosquito (Fig. 98).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

new-jersey/historic-themes-resources/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 14-Mar-2005