|

National Park Service

Historic Themes and Resources within the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail Route Southern New Jersey and the Delaware Bay: Cape May, Cumberland, and Salem Counties |

|

CHAPTER 7:

EDUCATION

The public schools in New Jersey did not receive significant attention until the beginning of the nineteenth century. During the colonial era, the proprietary government attempted to grant charters to the townships allowing land to be set aside for schools and the enactment of school taxes; but lawmakers failed to convince citizens of the importance of this. Thus, unlike colonies such as Massachusetts and Connecticut, schooling remained a private and parochial responsibility. [1]

In the South Jersey region, Quakers sponsored the earliest schools. Thomas Budd, a Quaker leader and intellectual, recorded the Quaker response to education in 1685 in the book Good Order Established in Pennsylvania and New Jersey in America: Being a True Account of the Country. In it Budd suggests that New Jersey legally require parents to enroll their children in school for at least seven years; that municipalities provide schools and teachers; and that boys and girls be instructed in reading, writing, arithmetic, English, Latin, and bookkeeping, in addition to boys learning a trade and girls learning spinning, weaving, knitting, sewing, and needlework. From 1746-87, Quakers made further efforts to ensure their children's education, recorded in the Rules of Discipline of the Yearly Meeting of Friends for Pennsylvania, Maryland, Delaware, and the Eastern Parts of Maryland. [2] One means was to entice knowledgeable teachers by offering them land for an ample homestead—as well as a salary. They also proposed that a collection taken at monthly meetings augment the teacher's salary or lessen the burden of tuition on poor families. Free, tax-supported public education was not instituted until the 1870s. A committee was also appointed to maintain the schools, gather funds, and review tutoring and teaching applicants. [3] The Old Stone School House, erected by Quakers in 1810 outside Greenwich in Cumberland County, is one of the oldest extant schools in the region (Fig. 99). Like a number of other early, vernacular stone schools in New Jersey, its simple rectangular form and scale, with hand-wrought details, is typical of a folk form associated with pre-homogenous cultural settlements.

|

| Figure 99. Old Stone School House, (1810, HABS No. NJ-222). One-and-one-half story sandstone walls are ca. 18" thick; shutters and doors are cedar with hand-forged hardware. HABS. |

Prior to 1817, the few public schools were supported solely by their respective communities. That year, however, the New Jersey Legislature first recognized the need for public education and provided for a state school fund. The Legislature invested $15,000 for a permanent public education fund; two years later this had increased to $113,238. By 1824, one-tenth of the state taxes were conferred to it annually, and townships were authorized to levy taxes to provide education for the poor, as well as to build and repair schools. [4] Despite recognition that education was a public and governmental responsibility, private schools continued to outnumber public institutions.

Private Institutions

One of the first private academies in the South Jersey area was Union Academy in Shiloh, founded in 1848-49 by Professor E.P. Larkin. The Seventh Day Baptists financed construction of its two-story, brick building that cost $10,000: The first floor housed recitation rooms and laboratories, the second a large hall. It remained a private institution until purchased by the public school district in the late nineteenth century. [5] Today it serves as the south wing of the Shiloh Elementary School; a 1920s addition, similar in scale, constitutes the north wing and building front. Though individually distinct and simply connected along one facade, this structure exemplifies the ongoing preference in form, scale, materials, and styling that prevailed in urban school construction through the mid twentieth century.

A year after Union Academy was founded, the West Jersey Academy for boys was established and supported by South Jersey Presbyterians. Construction commenced in 1852 on its building at West Broad and Lawrence streets. The stone building was three stories high with a basement and measured 53-1/2' x 60'. The academy opened to students in 1854 but by the 1880s it was no longer used and in disrepair. Bridgeton Middle School, formerly the Bridgeton High School, was built on this site in 1929. [6]

Additional private schools in Bridgeton included the Ivy Hall Seminary, Seven Gables School, and the South Jersey Institute. The Ivy Hall Seminary was founded in 1861 by Margaretta C. Sheppard as a boarding school for girls; it closed in the early twentieth century, but stands today at West Commerce Street and Aitken Drive. The Seven Gables School, also for girls, was founded in 1886 by Sarah Westcott. The building on Lake Street near the Bridgeton City Park, now a private residence, was built in 1872 and also served as a maternity hospital at one time. The South Jersey Institute, however, opened in 1870 as a boarding school for girls and boys; it functioned until 1907. [7]

The City of Salem was home to several private schools. The first, Salem Academy, was established in 1818, but the property on which it was built was given to the school by the Johnson family in 1787. Among the courses offered were English, Latin, and Greek. The building remained a school well into the early twentieth century. Several seminaries followed in the 1820s, including one operated by Joseph Stretch and another run by the Baptist Society. [8]

Perhaps the most noted private school in Salem County was the Salem Collegiate Institute, located on the corner of Broadway and Seventh street in the Rumsey Building. Founded in 1867 by the Reverend George W. Smiley as a girls' school, soon after it admitted boys, too. Two years later, when John H. Bechtel bought the institute, ninety pupils were enrolled; during his stewardship, the number increased to 190. Professor H.P. Davidson purchased the school in 1872. Davidson, despite opposition from the Friends of Free Education, a local reform group, and the national financial panic, improved it by adding a systematic curriculum of studies. Davidson also offered students hands-on learning. With his printing company, the students published the temperance and education newspaper The Alert. The institute continued to prosper well into the end of the nineteenth century. [9]

Public Institutions

In 1867 the Legislature took more extensive steps toward making education the responsibility of the state. The Constitution was amended to "provide for the maintenance and support of a thorough and efficient system of free public schools for the instruction of all the children in the State between the ages of 5 and 18 years." A ten-member State Board of Education was appointed by the governor, and provisions were made to appoint an education commissioner. Moreover, plans were made to maintain a normal school and a model training school, and to set up a board of examiners to review and license teachers. [10]

Throughout the end of the nineteenth century, the Legislature worked to improve the school systems. Between 1874-94, the number of school districts fell from 1,500 to 400. Five assistant commissioner posts were created with a county school superintendent, director of teacher training, normal school principals, and instructors. In the 1870s a new compulsory education law required that all children age 7 to 16 had to attend a day school or receive classes elsewhere. Children 14 to 16 with employment certificates were excepted. [11] The children of migrant-worker families escaped the notice of truant officers; even though they, too, were required to attend school according to the law, few were made to do so.

Bridgeton was the first urban area to set up a public school system. In 1847 the Bridgeton Township Free Public School, a three-story frame structure with ten rooms, was erected on Bank Street. It served white children 7 and older, though no more than two children per family were allowed to attend. A year later the Cohansey Public School, or Giles Street School, was built on the corner of Giles and Academy streets. Two stories high with four rooms, its curriculum was dispatched by three teachers. These schools set a precedent in that they were two of only twelve free public schools in the state of New Jersey; most public schools required some type of tuition. [12]

The existence of schools for black children is less documented. In 1862 a rented school room in the southern part of Bridgeton housed black students and a teacher. Ten years later, a county school survey referred to a rented one-story frame "colored school" composed of one room. Its exact location and name, however, is unknown and it may have been the same site. Local histories do not reveal how long the schools operated. [13]

As the population increased around the last quarter of the nineteenth century, more schools were erected in Bridgeton in the following order: Vine Street School (1866, 1906), South Avenue School (1873, 1903), Pearl Street School (1884, 1928), Irving Avenue School (1890s), and Monroe Street School (1899). At the turn of the century, many of the original schools were replaced by modern buildings or were remodeled. [14]

The first Vine Street School was frame; in 1906 it and the Giles Street School were replaced by the present Vine Street School (Figs. 100-101), now used as a board of education storage facility. The original South Avenue School was at the corner of South Avenue and Willow Street. At the turn of the century, it was used by the Henry Dix Factory as a manufactory of women's uniforms, and today it is the Samuel P. Roberts Elks Lodge where meetings and social functions are held. A new school building was constructed on another site in 1903; this building was destroyed by fire in 1975. The original Pearl Street School, a twin to the first South Avenue School, was built in 1884. It was replaced with the now-vacant Pearl Street School in 1928. The Irving Avenue and Monroe Street schools are the only facilities not replaced by newer buildings; the former has been incorporated into the Bridgeton Hospital complex while the latter is vacant. [15]

|

| Figure 100. Vine Street School (1906). The two-story, H-plan building has a formal three-part brick facade with hipped roof and raised basement. |

|

| Figure 101. Detail, Vine Street School, snowing wide eaves with beltcourse, and rusticated walls. Sebold. |

Bridgeton High School is one of the earliest high schools in New Jersey. Prior to 1892 the public school system was arranged in three levels: the youngest children in the primary grades, the middle age students were in secondary school, and older students were placed in grammar school. The term "high school" replaced grammar school in the late 1870s. The new Bridgeton High School was completed in 1893 and opened in January 1894. It was built on the site of the old Bank Street School of 1847. When high school attendance rose at the turn of the century, ninth-grade instruction was moved to the West Jersey Academy. The Board of Education purchased the academy in 1912, with plans to incorporate it into a new school building. But funds for the project were unavailable, and instead the academy was enlarged in 1922; the cornerstone for a new building was laid in 1929. The fate of the West Jersey Academy is unclear, Perhaps it is entombed in the new structure, which opened in 1930 and is still used as the Bridgeton Middle School. [16]

The biggest proponent of a public school in Salem was Samuel Copner. Although many townspeople did not relish taxation for education, Copner persisted and in 1850 a one and-one-half story brick structure was built on Walnut Street. A year later the school was increased to three stories. In 1860 a primary school was built on Market Street; it was used until 1869 when the Griffith Street School was opened. In 1873 the city leased the Salem Academy building to be used as yet another school. Finally, in 1879 a school for blacks opened on Broadway opposite the East Broadway Public Kindergarten. In 1900, the following private and public schools operated in Salem: East Broadway Public Kindergarten at 365 E. Broadway, Friends School and Kindergarten at Broadway and Walnut streets, Salem High School on Market Street, Public School No. 5 on Broadway, Richard M. Acton School on Walnut Street, St. Mary's Parochial on Oak Street near Carpenter Street, and Samuel Copner Public School on Grant Street near Seventh Street. [17]

In 1905, the Salem Grammar School was built as a high school. Eight years later, however, the increasing number of students required that a new high school be built on New Market Street. In the 1930s it too was enlarged, and today it operates as a middle school. [18]

The first school in Millville was built in 1800; public but not free, the tuition was used to pay the teacher's salary. In 1849 Millville's first free facility, the Central School, was constructed at a site on the corner of Third and Sassafras streets. The building served 300 students in the 1850s, but it could accommodate 150 more. The number of students increased when Sanford Culver became principal. Millville's education system benefitted from Culver as he was responsible for establishing the first high school on the third floor of the Central School. It was then renamed the Culver School. In 1909 the school was torn down and a new one was built. The latter, also called Culver School, is on Third Street and currently serves as an elementary school. [19]

By 1860, Millville needed a new school to accommodate the children of immigrant workers. To remedy this problem, the Furnace School, which seated 350 students, was built in 1862 on the corner of Powell and Dock streets. Eleven years later another, the Western School, was opened on the west side of Millville on Pike Avenue. In 1906 it was abandoned and a new Western School was built on Howard Street and Park Avenue. It was remodeled in 1913 to include four additional rooms; since 1983 it has been used as a warehouse. [20]

Other schools erected in Millville in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century include: Eastern or Southeastern School (1872) on South Fourth Street, Northeastern School (1878) on North Fourth Street, South Millville School (1879) on South Second Street, and New Furnace School (1882) on the corner of Archer and McNeal streets. The large number of schools built between 1872-82 reflects the rapid growth of Millville during that era. However, more were needed at the turn of the century. Among those built were the Culver School (1911) on Third Street, the R.D. Wood School (1916) (which replaced the old Furnace School on Powell and Dock streets), Memorial High School (1925) on Fifth and Broad streets, and the R.M. Bacon School (1929) on South Third Street. [21]

South Jersey's extant nineteenth- and early twentieth-century urban schools share certain structural and stylistic forms. In areas where the population and economy flourished, large, comfortable, and more permanent structures predominate. Expensive and well-crafted materials such as stone and brick are employed in designs that adhere to formal principles of proportion, scale, and ornament—with Classical Revival and Italian Renaissance Revival being two popular styles.

Two examples of these fine nineteenth- and twentieth-century schools are Bridgeton's Vine Street School and Millville's Memorial School. Vine Street is constructed in an Italian Renaissance palazzo style, with large chimneys and fancy brickwork. The Millville Memorial School, an elegant, one-story, Italian Renaissance-style structure with arcade-like openings along the front facade, was built to commemorate local citizens who died in World War I. The entrance features their names and the names of others who gave their lives in subsequent wars inscribed in a placque. Originally built as a high school, it now serves middle-school students.

Today most of these facilities—if still in use—serve as elementary schools. New area high schools were built in the 1960s and are large enough not only to accommodate students from the respective towns, but also the school-age residents of the surrounding townships. As a result, use of rural schools has declined since the mid twentieth century. Historically, as well as today, it is common for children to attend elementary and middle schools in their township, and then travel to high schools in Salem, Bridgeton, or Millville. Despite having fallen into disuse, however, examples of the rural township schools are extant and in good condition.

Rural/Country Schools

By and large the extant rural schools in South Jersey are stylistically folk or mass-vernacular. The simple one- or two-story frame buildings are painted white, with a gable roof and gable-end door. Here, as was common elsewhere, "schools also reflected forms used in neighboring communities and other structures such as houses and agriculture and civic buildings." [22] The temple-like form and color echo the Classical Revival idealism that swept the nation during the nineteenth century. Dimensions were determined by how far the teacher's voice could carry, thus schools typically measured 30' x 40', 20' x 30', 24' x 36', etc., large enough to accommodate about thirty or forty students. [23]

The majority of extant country schools are lookalike, modest, gable-roofed frame buildings constructed of commercially produced and dimensioned materials and manufactured hardware, but incorporate provincialized ornamentation; many have been adapted to a new use. The forms, built from the mid to late 1800s, are repeated in nearby churches, community centers, granges and masonic halls. Foremost among these is the two-story, front-facing gable block, some more elaborate than others. During the last quarter of the nineteenth century, these were more substantial constructions thanks to balloon-frame technology, and exteriors usually covered with clap board. This school form is rarely found west of the Mississippi River. [24]

Almost every small town contained its own school. Five existed in Cumberland County outside Millville, all built between 1870-76: Pine Grove School on Bridgeton Millville Pike; Farmington School on the road from Bridgeton to Buckshutem; Centre Grove School at the junction of Buckshutem, Bridgeton, and Millville roads; and Menantico School on the road to Port Elizabeth. [25] Also, Mauricetown, Haleyville, Port Norris, Turkey Point, Dividing Creek, Fairton, Dorchester, and Greenwich had one school each; Cedarville had two. [26]

At the turn of the century in Salem County, the number of schools per township varied; most appeared to be associated with a town of several hundred or more residents. Hancock's Bridge (population 300) in Lower Alloways Township had one public school that went to the eighth grade, and Pennsville (population 600) in Lower Penns Neck Township also had one public school. Quinton's Bridge (population 750) in Quinton Township had two public schools. Prior to the twentieth century, most schools in rural Salem County appear to be associated with small towns and crossroads. [27]

At the turn of the century, many of the small towns west of today's Route 47 in Cape May County also had community schools. The following towns had one public school: Cape May Point, Dias Creek, Fishing Creek, Green Creek, Rio Grande, South Dennis, and Goshen. The latter's school covered both primary and grammar grades. Cold Spring had two schools; one was graded, the other was not. Dennisville had both primary and grammar schools. Many of these appear to have opened prior to the twentieth century. [28]

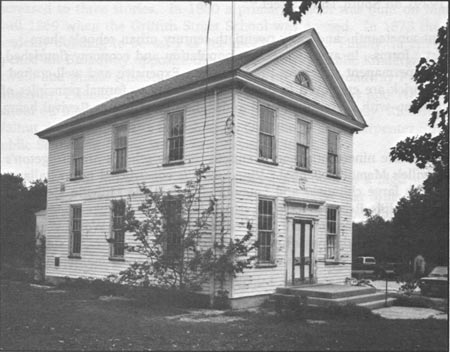

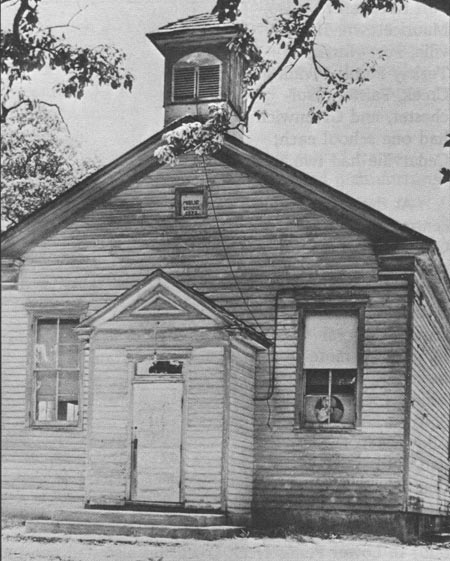

The best preserved examples of two-story mass-vernacular buildings are found in the Mauricetown Academy (1860, Fig. 102), the Goshen Public School (1872, Fig. 103), and the Haleyville School (1875)—in the respective towns. Each are frame and two stories tall, with the front gable end facing the road. If not for slightly varying ornamentation, these boxy, rectangular schools are identical. Goshen School is the only one with a square cupola at the front gable end, which probably housed the bell used to summon students—a feature that served as something of a status symbol. Fishing Creek School, now a private residence, is a one-story, clapboard structure with cornerboards. [29] The now-lost Buckshutem School (1875, Fig. 104) also had a cupola. [30] Other typical one-story schoolhouses are found in the Lower Hopewell Township School (1859) and Centre Grove School (1876); both are plain with a low-pitched roof.

|

| Figure 102. Mauricetown Academy (1860). The entry is in the gable end, secondary doors to the side; the pediment has a dentiled cornice and semi-lune. |

|

| Figure 103. Goshen Public School (1872), with community building in background. Main gable-end entry and seven-bay side facades with banked windows offer improved light and ventilation. |

|

| Figure 104. Buckshutem Pubic School (1875). The traditional gable front with returning cornice is topped by a cupola. Rutgers University, early 20th century. |

There is some similarity among mid to late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century schools. The Lower Hopewell Township School (1859, Fig. 105), for instance, is a rectangular form with a typical gable end doorway and another on the long side facade; two small windows flank each side of the door, which also features a braced gable roof. Built approximately a half-century later, the one-story Downe Township Primary School and the brick bungalow-styled school near Delmont are not dissimilar. The former is a side-facing rectangular form that features a double-door entrance and flanking windows, although the facade is overshadowed by the steeply pitched hip roof and exposed rafters. [31] The latter is a purer building type that may have been a patternbook derivation.

|

| Figure 105. Lower Hopewell School (1859) has been somewhat altered, but it retains the vernacular Greek Revival form popular during the 19th century. Leach. |

Libraries

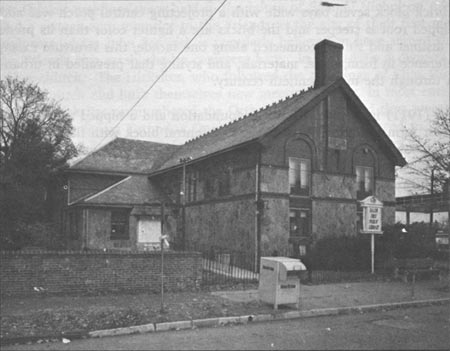

Most libraries in South Jersey are housed in recently built structures in urban centers. Two older examples, however, are found in the Salem Free Public Library or John Tyler Building (1885), and the Bridgeton Public Library.

The Bridgeton Public Library (1816), relatively old for the region, is a brick, Federal style building with a gable roof and decorative cornice highlighted with dentil molding. The structure, which has served as the library since 1886, was originally erected as the Cumberland National Bank and was moved to its present location in 1886 (when the present Cumberland National Bank was erected at the former site). Prior to this, Bridgeton does not appear to have had a library. The Salem Free Public Library (Fig. 106), named for John Tyler who revived local interest in the library in 1863 and served as the library board president in the same year, is an architecturally unusual building for the area because of its whimsical Victorian detailing. The library in Salem was originally founded by subscribers on 14 June 1804. In 1809 the Library Company of Salem disbanded and it did not resume until 1843. The company was disbanded again until 1863, when John Tyler worked to reorganize the library, which has remained a vital part of the community. [32]

|

| Figure 106. Salem Free Public Library (1885). The library is also called the John Tyler building, named for the president of the library board in 1863. |

Descriptions of Additional Historic Resources

Shiloh Elementary School/Union Academy (1848-49, 1920). The two-story, rectangular brick block is simple, but features tall windows separated by full-height brick pilasters. The shallow, hipped roof is topped with a square cupola that contains a bell. A similar-scaled rectangular brick block seven bays wide with a projecting central porch was added in the 1920s; its hipped roof is steeper and the bricks are a lighter color than its predecessor. Individually distinct and simply connected along one facade, this structure exemplifies the ongoing preference in form, scale, materials, and styling that prevailed in urban school construction through the mid twentieth century.

Culver School (1911) is brick with a stone foundation and a hipped roof with a low pitch. The rectangular form is created by a three-story central block with flanking two-story wings. There are two double doorways between the main block and the wings that feature an arched transom; beneath the left one is the word "GIRLS," beneath the right is "BOYS." The Monroe Street School in Bridgeton also had separate entrances for boys and girls.

The R.D. Wood School (1916) is constructed of brick, but the three-story rectangular block is a more reserved and open Classical Revival design. It features a raised, rusticated basement, but the first- and second-floor facades are made up largely of multi-light, banded windows with some awning openings, which indicate a later construction date and awareness of what new technologies could offer. The styling is maintained, however, using the full-height pilasters between the bays, and a heavy cornice that obscures the low-pitched hipped roof. The double entry doors are topped with semicircular transoms contrasted by the arched door surround with central keystone.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

new-jersey/historic-themes-resources/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 14-Mar-2005