|

National Park Service

Historic Themes and Resources within the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail Route Southern New Jersey and the Delaware Bay: Cape May, Cumberland, and Salem Counties |

|

CHAPTER 8:

RELIGION

Before 1700, most of the settlers in Salem, Cumberland, and Cape May counties worshipped as Quakers, Baptists or Presbyterians. By 1775, the South Jersey area was dominated more or less equitably by congregations of Presbyterians, Baptists, and Friends, in addition to a small number of Methodists and Lutherans. By 1860 Methodism abounded, followed by smaller numbers of Baptists, Presbyterians, and Friends; and by 1890, Methodists far outnumbered all other sects. [1] This pattern of religious development is reflected in the extant churches. The religious buildings here fall into three groups: Quaker meeting houses, gable-front Greek Revival forms with and without gable-end spires, and irregular-plan Victorian compositions with towers and wings. The oldest structures in the New Jersey Coastal Heritage Trail area reflect the first two; most rural examples are frame, while the Quaker and urban structures are typically brick.

Quakers

The Quakers appear to have been the most influential in the seventeenth century along the shores of the Delaware River, where they are attributed with founding Salem, Penns Neck, and Greenwich. Eventually some, like Richard Hancock, left the waterside environs for interior towns that were more typically settled by Baptists or Presbyterians.

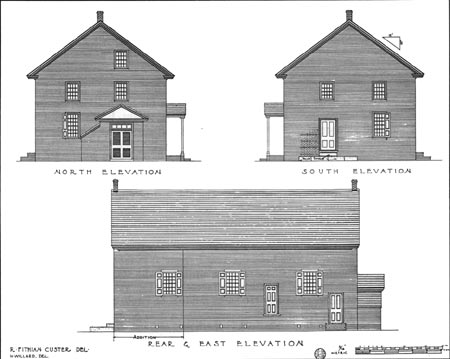

The first Quaker meetings were held in the house of Samuel Nicholson near Salem. In 1681, he deeded a sixteen-acre town lot to the Friends as the site of their first meeting house—beneath an oak tree where John Fenwick is popularly believed to have signed the treaty with the Indians; the Friends also established a cemetery here. In the 1820s a division occurred within the Quaker church. The Hicksites, who followed the teachings of Elias Hicks, broke from the Orthodox church and built themselves new meeting houses, in most cases. In Salem, however, the Hicksites outnumbered the Orthodox Quakers and thus were able to keep the original church. The Salem Orthodox Quakers, as a result, were forced to build a new church on West Broadway in 1837. Before the church was completed they met in a schoolhouse on Walnut Street. Between 1679 and 1725, other meeting houses were built in Elsinboro, Alloways Creek, Greenwich (Fig. 107), Hancock's Bridge, and Woodstown. [2]

|

| Figure 107. Old Friends Meeting House (1779, HABS No. NJ-105). Two bays by five bays, the front facade is Flemish bond. Separate entries and interior seating are provided for men and women. |

Many of the Quakers who settled in today's Salem and Cumberland counties arrived with Fenwick; the Quakers who helped found Cape May, however, came from New England. They erected their first meeting house in Seaville (outside the study area) and a second in Town Bank, in 1717, on property donated by John Townsend. [3] Within the NJCHT there are four active Quaker meeting houses, most of which are located west of the Cohansey River in Salem County. These brick, gable-roof structures, erected and added to throughout the eighteenth century, reflect a purity of architecture and Quaker tenets alike. The meeting houses are largely identical, even those built into the next century, because:

Although the early Friends probably had no intention of creating a distinct type when they planned their places of worship, once that type was clearly defined and had become hallowed by tradition, they clung to it with characteristic tenacity. The advent of the Georgian barely touched the meeting house, the classical revival came and went leaving it unchanged. [4]

Associated with many meeting houses are Friends cemeteries, noteworthy because until the late eighteenth century Quakers believed gravestones should be proper and simple—or without markings. Two exemplary sites are near the Greenwich and Salem meeting houses, where they are surrounded by stone walls. The Greenwich cemetery has no markers, but Salem's does because it contains late eighteenth-century burials; thus, part of the latter cemetery mistakenly appears vacant.

The Friends' beliefs were not only reflected in the purity of their architecture; it extended to their attitude toward social conventions, especially slavery. In 1696 they opposed the importation of slaves, and by 1776 barred membership to slaveholders. Quaker protests helped subdue the laws against blacks. In 1768 special courts that dealt with blacks were abolished; in 1769 a special tax was levied on each slave imported into New Jersey; and in 1778 special laws aimed at crimes committed by blacks were abolished. By 1794, South Jersey had three antislavery societies, at Trenton, Burlington, and Salem. [5]

In addition to being ardent abolitionists, the Quakers also abetted runaway slaves. New Jersey was the first free state en route north from Virginia and the Delaware-Maryland peninsula, and as early as 1786 South Jersey was known for its efforts. By 1810 it offered a network of many safe, secret shelters to guide the fugitives northward along what would become known as the Underground Railroad. Many slaves came from the Chesapeake Bay region and Delaware via three principal routes: the Delaware River from Camden to Burlington, then through Bordentown, Princeton, and New Brunswick; from Salem through Woodbury and Mount Laurel, then joining with the first route at Bordentown; and by way of Greenwich to Swedesboro to Mount Holly, to meet with the Burlington route. South Jersey's Underground Railroad, with Quaker support, is estimated to have aided approximately 50,000 slaves escape to freedom. Harriet Tubman frequently used it in her efforts, and she supposedly worked in Cape May to raise money to support her expeditions. [6]

Some historic Quaker-built homes in Salem County may contain an alleged "secret room" once used to hide runaway slaves—a difficult claim to prove because of the intentional lack of evidence. One such site is the Abbott Tide-Mill Farm outside Salem. The 1845 Federal-style mansion features an old, underground cistern accessed by a crude trap door that had long been hidden beneath contemporary cabinetry. The Abbotts, a Quaker family, support the oral history tradition of this "room's" use through abundant written documentation—family papers, maps, and other records—though additional research is required to ascertain whether or not there is evidence for the claim.

Baptists

The Quakers, however, were not the only religious group to express radical social beliefs. As early as 1675, the first Baptists arrived in Cape May County, including George Taylor and Phillip Hill. The first congregation was formed in 1712, with meetings held in private homes for three years, until a church was built on Leaming Plantation near Rio Grande. [7]

The first Baptist church was established in Salem County in 1683 by David Sheppard, Thomas Abbott, William Button, Obadiah Holmes, and John Cornelius. Thomas Killingsworth served as the first preacher, as well as an early judge in Salem County. In 1690 these men built a frame Cohansey Baptist Church; a second building was erected in 1741, and in 1801 the congregation moved to Roadstown where the present Cohansey Baptist Church (Fig. 108) was erected.

|

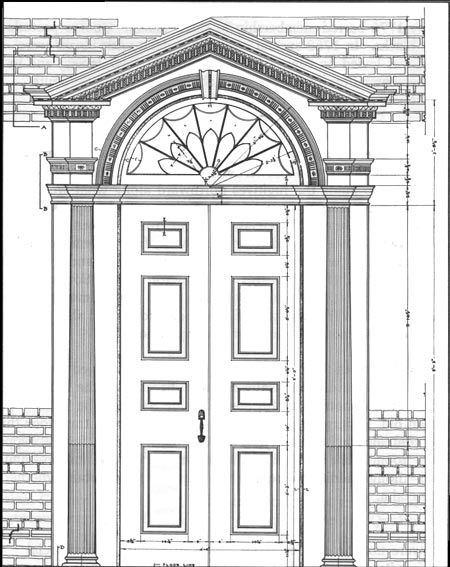

| Figure 108. Cohansey Baptist Church (NJ-463) is highlighted by frame pediments and pedimented Georgian doorways such as this, plus round-arched windows with nine-over-nine-lights. |

Three years before the original Cohansey Baptist was constructed, the congregation split. Reverend Timothy Brooks led the new group to Bowentown, outside Bridgeton, where they built what would emerge as the Seventh Day Baptist Church. Unlike Killingsworth's followers, the Seventh Day Baptists believed the Sabbath should be observed on Saturday instead of Sunday. In 1710, the Bowentown congregation united with other Seventh Day Baptists and built a new church on land given to them by Robert Ayars. Ayars' land and the church later became part of the town of Shiloh. [8]

Roger Maul gave land for a new church to Baptists in the Back Neck area, near New England Town, in 1713; during the next three decades, more Baptist churches were organized in the area. In 1790 the Baptists of Mill Hollow and Salem united to erect the First Baptist Church in that city. Robert Kelsey, minister of Cohansey Baptist Church in Cumberland County, also preached at the courthouse in Bridgeton. His successor, Henry Smalley, continued this practice into the nineteenth century. Services were held there until 1816, when construction began on the First Baptist Church. In 1853, the congregation moved downtown and the Pearl Street Baptist Church replaced it. [9]

The Shiloh Baptist Church, in keeping with the straightforward tenets of that faith, is reserved and well proportioned, with an unadorned frontal pediment and wide, plain cornice. Tall, narrow sash flank the central door, which boasts a prominent surround (though the doors themselves are contemporary glass). Plain brick pilasters—single on the front, paired on the sides—punctuate the tall, paired fenestration.

Baptists arrived to the southern part of Cumberland County from Cape May and the Cohansey River area in the mid eighteenth century. One of the first Baptist churches in the area was erected in Dividing Creek in 1751. It served the Newport and Port Norris region, as well. In 1821 a second building (erected 1771) was destroyed by fire. A new church was built and dedicated in 1823. In 1855 the church allowed fifty-one members to form their own church in Newport. A year later the Port Norris members were given permission to start their own church. The dismissals of the Newport and Port Norris members did not eliminate the problem of overcrowding and in 1860 the Dividing Creek church was enlarged. [10]

Cedarville was also the location of an early Baptist church. Baptists lived in the Fairfield Township area near Cedarville but did not organize until 1836. Although Nathan Lawrence, a prominent Cedarville resident and Baptist, left a plot of land to the church upon his death at mid century, no building was erected at the time. The first Cedarville Baptist Church was built, instead, on land owned by Butler Newcomb, a deacon of the Dividing Creek Baptist Church. Upon Newcomb's death the church was willed the money with which to purchase land and building. In 1836 the church was moved to a more central spot on Main Street where it still exists. [11]

Presbyterians

The Presbyterians were the third religious group to establish a church in Fenwick's Colony in the seventeenth century. Like the Baptists, the Presbyterians came from New York and New England, and settled on both shores of the Cohansey River in 1680-85. [12] Due to this settlement pattern, some resided in Greenwich on the west bank, others lived in Fairton on the eastern shore. A church was organized in Fairton in 1695, and for ten years—until a church was built in Greenwich—the Greenwich residents ferried across the river to attend services. [13]

A century later, Greenwich native Philip Vickers Fithian officiated at services at his town's Presbyterian church and those of surrounding areas. Fithian graduated from Princeton University in 1772, after which he spent a year in the seminary, then another year serving as a tutor at Robert Carter's Nomini Hall in Virginia. In 1774, when he returned to New Jersey, Fithian was licensed to preach by the Philadelphia Presbytery. He worked in the Greenwich area and participated in the burning of the tea on the town square. In May 1775 he began a tour as chaplain with the revolutionary forces, but the next year he died of dysentery in a camp outside New York City. Fithian is best known for his journals, which depict eighteenth-century life in New Jersey and Virginia. [14]

The Old Stone Church/Fairton Presbyterian Church (1780, Fig. 120) reflects the influence of Quaker building traditions on the New England Presbyterians; the appearance and basic configuration is like a meeting house, but highlighted by Georgian ideals of proportion and decoration. It also bodes of the boxy, Greek Revival form that would became popular almost a century later, with its two stories and rectangular plan with three bays on each side, topped with a slate-covered gable roof. Church and cemetery are surrounded by a later, elaborate Victorian-era cast-iron fence. [15]

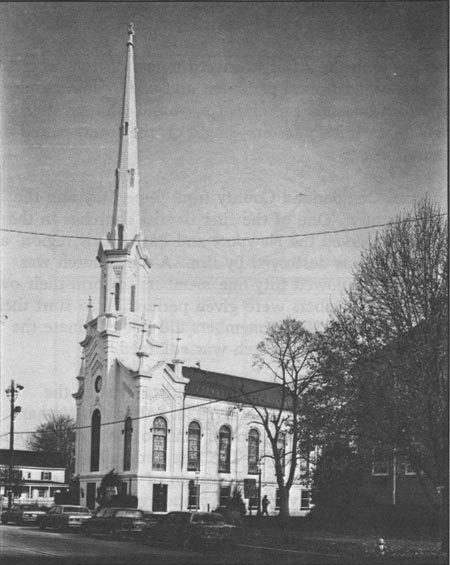

The first Presbyterian Church built in Salem proper was in place in 1821 thanks to Robert Gibbon Johnson and other Presbyterians, after they were denied permission to share the Episcopalian church. [16] The First Presbyterian Church (Fig. 109) in Salem is one of the most exuberant in the region. It was designed by Philadelphia architect John McArthur Jr. (1823-90), who served as chief architect of Philadelphia City Hall in 1869, as well as the designer of numerous residences, churches, and commercial buildings. [17] The main facade features a series of recessed walls and borders. The verticality of the building is enhanced by its tall, round arched windows, decorative blind arcading, and dramatic 165' spire. It represents eclectic inspiration from several late nineteenth-century movements, especially Romanesque Revival.

|

| Figure 109. First Presbyterian Church (1856) facade has a projected entrance with a series of recessed facade and cornice lines, decorated steeple base and matching narthex-end walls. |

Bridgeton did not have a Presbyterian church until 1791, when Quaker Mark Miller donated a lot to the city for the purpose of building one with a burial ground. Broad Street Presbyterian Church, 1792-95, is the oldest of this denomination in the region, and its cemetery contains the graves of Cumberland County men who died in the Civil War. [18] Located in an elevated urban setting also accompanied by a spacious, tree-filled burial ground, the area serves a parklike function.

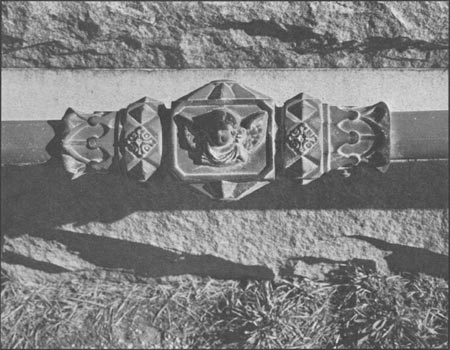

In Cape May County, the Presbyterians were organized in 1714 at Cold Spring. Similarly, services were held in private homes until 1718 when the congregation erected a small log cabin church. The adjacent cemetery, along with the original cemetery at Stone Presbyterian in Fairfield Township, contain some of the oldest grave markers in the area; many at Cold Spring commemorate men who lost their lives at sea. [19] The present Cold Spring Presbyterian Church (1823, Fig. 110) is two-story, brick gable front with little ornamentation. One of the most interesting features of this site is the ironwork found in the adjacent cemetery, which contains the plots of noteworthy local citizens whose prosperity is reflected in the accoutrements of the iron fencing—especially faces, figures, and urns (Fig. 111).

|

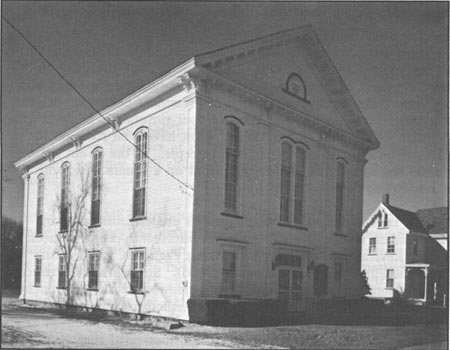

| Figure 110. Cold Spring Presbyterian Church (1823, NJ-270). Two-story brick, with cornice and pediment with dentils. Three bays wide by four bays deep. |

|

| Figure 111. Ironwork, Cold Spring Presbyterian Cemetery, includes this Victorian cherub-face railing draped urn, willow tree, reaper figure, and swag-with-tassel. |

Methodists

The Methodists organized in Salem County in the late eighteenth century, though by the late nineteenth century their numbers proliferated beyond all other religious groups. In 1772 Benjamin Abbott of Pittsgrove Township, a religious skeptic and acknowledged drinker, had a dream that converted him into a fire-and-brimstone evangelist who succeeded in uniting Methodists in Salem and inspiring others as far away as the Eastern Shore of Maryland. After his conversion, Abbott worked with John Murphy, a neighbor, to put together a Methodist congregation in Pittsgrove Township. Murphy opened his home to Methodist itinerants and soon the first Methodist Society in Salem County commenced worshipping. A church was built on Murphy's land shortly thereafter.

In 1774, Abbott moved to Mannington Township and helped Daniel Ruff, an itinerant preacher, to introduce Methodism to Salem. Abbott's congregation held its meetings in a barn-like building until 1784 when several Quakers financed the construction of a church on Walnut Street in Salem. By 1826 the number of Methodists in Salem had grown so rapidly that the church on Walnut Street could no longer accommodate them. As a result, the congregation built and dedicated a new church in 1838. Twenty years later, part of the congregation split and built yet another new church on Broadway. The Broadway United Methodist Church is extant today. [20]

Methodism soon spread beyond Salem into Quinton's Bridge and Lower Penn's Neck. It also spread into many parts of Cumberland County. As early as 1800, a Methodist Society was present in Newport. The society was organized by a Captain Webb and meetings were held in the sail loft of Jonathan Sockwell's barn. In 1814 the barn was remodeled into a church, which burned down seven years later. An intermediate structure was utilized until 1852 when the present structure was built on property bought from Sheppard Robbins. [21]

In 1804 Methodists in Bridgeton were organized under the leadership of William Brooks; three years later Jeremiah Buck donated a lot on Commerce Street for the first Methodist church. Two years after the formation of the Methodist Society in Bridgeton, one was formed in Leesburg. After meeting in private homes for five years, the society was incorporated and a new church built. Branches were formed off the Leesburg church in 1856 when the membership became too large. As a result, the members from Dorchester formed their own society and built a new church in 1863. [22]

The Mauricetown and Haleyville Methodist Episcopal societies formed in the early nineteenth century and were served by the same pastors until 1881. The exact date of the first church in Haleyville is unknown, but the existing church was built in 1864. In 1841 the first Methodist church was built in Mauricetown. Its congregation used the church until 1880 when it was moved to a new site, turned into the town hall, and replaced by a new building. The congregation dedicated several of the stained-glass windows in the new church to the men who lost their lives at sea. [23]

Millville's first Methodist Society was organized in 1807 when the Cumberland circuit was set off from the Salem circuit. In 1824 Trinity Methodist Church, located on Second and Smith streets, commenced holding services. Forty-two years later, a portion of the congregation constructed a new building on Second and Pine streets; this is the First Methodist Church. Today the Methodists of Millville are served by seven different churches. [24]

Methodists organized in Cedarville before 1820 held meetings in the local wheelwright shop. The present church was built in 1863. Dividing Creek and Port Norris did not have a Methodist society until the mid to late nineteenth century. The Methodists in Dividing Creek organized in the 1840s but shared a preacher with the Newport Methodist Church. The Port Norris congregation organized in 1871 only after breaking away from the Haleyville church. [25]

Among the nineteenth-century gable-front churches are three constructed of brick: the Broadway Methodist Church (1858) and Mt. Pisgah AME Church (1878) in Salem, and Cedarville Methodist Church (1868, Fig. 112). Broadway Methodist is very stylized, with round-arched windows, brick pilasters, a formal frame pediment with dentils, and a rusticated door on the main facade. Broadway Methodist was surely the model for the third structure, Mt. Pisgah AME, built twenty years later.

|

| Figure 112. Cedarville Methodist Church. The two-story gable-front frame block is three bays by four bays, with a deep pediment and decorative cornerboard pilasters. |

Frame variations include the Haleyville Methodist Church (1864), the Trinity [United] Methodist Church (1870) in South Dennis, the Dennisville United Methodist Church (1870), and the Dias Creek United Methodist Church (ca. 1870). Each has a three-bay gable-front facade, and is three or four bays deep, with twelve-over-twelve-over-twelve-light wood sash and tall louvered shutters. Their Greek Revival foundation of prominent pediment with full cornice or broken returns, pilaster cornerboards, and classical door surround is blended with late nineteenth-century Victorian details such as bracketing. Most have pent roofs on the gable end; all except the Haleyville church boast a gable-end steeple. At the South Dennis and Dennisville churches these rest at the fore of the gable front on a square base, with a squat roof and lean spire, respectively.

The third church type is later and more elaborate than its predecessors, with an irregular plan, profile, and abundant texture—typical of the late nineteenth-century Queen Anne, Romanesque and Gothic Revivals. Salem boasts the oldest examples, in St. John's Episcopal Church (1811) and the First Presbyterian Church (1856). St. John's is constructed of granite and has many Gothic details, such as pointed-arch windows and a steeply pitched roof. Goshen Methodist Church (ca. 1870, Fig. 113), Newport Methodist Church (1852), and Dividing Creek Methodist Church (ca. 1850-60) illustrate this form in frame: the tower at the inside of the L features the main doorway, an exposed belfry, and four-sided roof. With their colorful round- and pointed-arch stained-glass windows a sharp contrast to the white exteriors, these cheerful and delicate buildings were erected by the abundant Methodist congregations in the 1870s-90s.

|

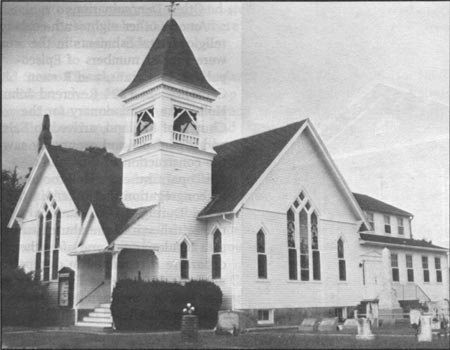

| Figure 113. Goshen Methodist Church (ca. 1870). This church is an example of the irregular Victorian plan and abundant architectural texture. Leach. |

African Methodist Episcopal (AME)

The first African Methodist Episcopal Church in New Jersey was formed in Salem in 1800. Several upstanding members of Salem's black community, Reuben Cuff, Chauncey Moore, and Cuffie Miller, purchased the land for their church. Worship services commenced in 1802, though the church was unfinished. Mt. Pisgah United Methodist Church burned in 1839 and the present edifice was built in 1878 with a datestone inscribed: "Built 1878 - Mt. Pisgah AME Church - For the people had a mind to work" (Fig. 114). The Mt. Pisgah congregation was one of the first five African Methodist Episcopal (AME) churches in the nation. Moreover, Reuben Cuff was one of the original sixteen founders of the AME conference in Philadelphia in 1816. [26] By the end of the nineteenth century AME churches could be found in Quinton, Mannington, and Pilesgrove townships.

|

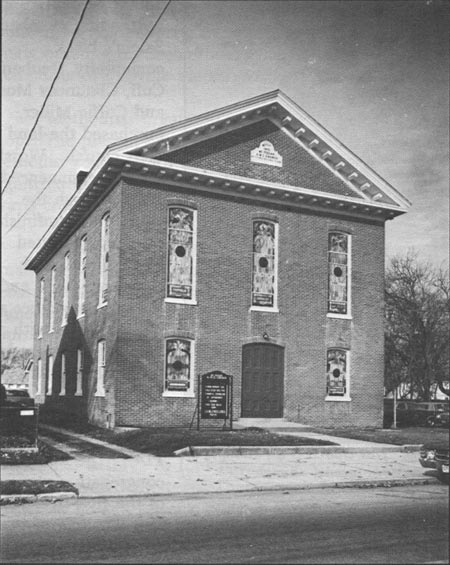

| Figure 114. Mt. Pisgah AME Church is a two-story, three-bay brick block with a gable-front, deep pediment, and stained-glass windows. |

Other AME churches opened their doors to worshippers in the early and mid nineteenth century in Cumberland and Cape May counties. An AME congregation was organized in Gouldtown, an early black settlement, by Reverend Jeremiah Miller in 1818. The first meetings were held in different homes, with the Quarterly Conference congregating in the barn of Furman Gould. The first church was built in 1825, a second one in 1836. In Cumberland County the AME churches are found in Bridgeton in 1854, established by Reverend Caleb Woodyard; in Haleyville in 1882, by Reverend E.P. Grinage; in Millville by Reverend W.M. Watson; in Port Elizabeth in 1836 by Noah Cannon; and in Springtown in 1817, with Clayton Durham as the first pastor. Cape May County's AME churches included one at Cape May Point, founded in 1883 by Reverend G.T. Waters; another at Cold Spring prior to 1841, and another in Cape May prior to 1843. [27] Today, AME churches and several Baptist churches exist in South Jersey. Among them are Bethel AME in Port Norris and Mt. Pisgah AME in Salem.

Other Denominations

Among other eighteenth-century religious establishments in the area were smaller numbers of Episcopalians, Lutherans, and Roman Catholics. In 1724 Reverend John Holbrooke, a missionary for the Church of England, arrived in Salem and organized—and eventually saw to the construction of—St. John's Episcopal Church. Holbrooke served its congregation and others in the area. During the Revolutionary War, the British seized the church to use as a headquarters, and after their departure it remained in disrepair until the 1800s. The Episcopalians also built a church in 1729 that exists in Othello. [28]

In the mid eighteenth century, the first Roman Catholics and German Lutherans appeared in Salem County. The members of these two organizations worked for Casper Wistar in his glass factory near Alloway. The Lutherans established a church at Friesburg in Alloway Township in 1748. The Catholics arrived ten years previous to the Lutherans, however, they did not establish a church until 1852. Until the Revolutionary War Catholics were often restricted from worshiping openly. [29]

Description of Additional Historic Resources

Greenwich Meeting House (1779, HABS No. NJ-441). Two bays deep and six bays long, the front facade is laid in Flemish bond and other walls in a five-course common bond. Built in two sections, this building provides separate entries for men and women; internally, following tradition, the sexes are seated separately. Each entrance is adorned with a pediment and simple porch supports. As with all meeting houses, the womens' entrance has a saddle door several feet high, which allowed them to access the carriage without touching the ground. First-floor fenestration is twelve-over-twelve-light double-hung sash, with elliptical arch-topped piercings on the men's side; second-story windows are six-over-six-light wood sash. All windows have paneled shutters; there are two interior gable-end chimneys and the roof is covered with cedar shingles.

Old Stone Church/Fairton Presbyterian Church (1780, HABS No. NJ-273). Built of dark, local sandstone, the gable ends are laid up in rubble while the more important side facades are coursed; the corners feature stone quoins. The windows contain nine-over-nine-light sash, the first floor with panelled shutters, and there are two double-door entrances. This church and its cemetery are surrounded by a later, elaborate Victorian-era cast-iron fence. [30]

Old Broad Street Presbyterian Church, Bridgeton (1792). Blends high-style Georgian features with the local tradition. Here, the Flemish-bond structure is five bays on the long east and west facades, three on the gable ends; a beltcourse and watertable are also articulated. The windows have very formal arched openings atop twelve-over-twelve-light wood sash, the doorway features a pedimented surround, and the roof pediment is pronounced.

Dias Creek Church (ca. 1880), Dias Creek. This structure is relatively unique in that it features a vestibule whose form mimics the main block; its center steeple rises from a canted base over the vestibule, to a secondary roof, open belfry, and last a polygonal spire.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

new-jersey/historic-themes-resources/chap8.htm

Last Updated: 14-Mar-2005