|

Old Spanish National Historic Trail AZ-CA-CO-NV-NM-UT |

|

NPS photo | |

...the longest, crookedest, most arduous pack mule route in the history of America...

—LeRoy and Ann Hafen

It is 1829, eight years after Mexico gained independence from Spain. New Mexican traders travel overland to establish new commercial relations with frontier settlements in California. They carry locally produced merchandise to exchange for mules and horses. Items include serapes, blankets, ponchos, and socks; a variety of hides — gamuzas (chamois), buffalo robes, bear, and beaver skins; as well as hats, shawls, and quilts.

By this time Santa Fe is witnessing increased economic activity brought on by successful American and Mexican trade. Large quantities of manufactured products arrive in New Mexico from the eastern United States along the Santa Fe Trail. Many goods are also traveling along El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro to and from the interior of Mexico.

Connecting Two Mexican Provinces

In 1829, La Villa Real de Santa Fe de San Francisco de Asis, provincial capital of New Mexico, was just a dusty frontier town that sheltered a mix of Spanish colonial families, newer Mexican arrivals, displaced Indians, and a small but growing number of Americans. Over 1,000 miles to the west, the Pueblo de la Reina de los Angeles was an even smaller ranch town. Consisting of little more than a church and plaza, and a few homes and government buildings, it was the largest Mexican community in an area characterized by dispersed ranches, decaying Spanish missions, and Indian villages.

During the winter of 1829-1830, Antonio Armijo led a caravan of 60 men and 100 pack mules from New Mexico to Mission San Gabriel in California, east of Los Angeles. The caravan carried woolen rugs and blankets produced in New Mexico to trade for horses and mules.

Other trade parties soon followed. Some found alternative routes that together became known as the Old Spanish Trail. It took Armijo's group about 12 weeks to reach California and six weeks to return on the trail historians LeRoy and Ann Hafen called, "the longest, crookedest, most arduous pack mule route in the history of America."

Mules and Men

The lands crossed by the Old Spanish Trail were alluring. For decades missionaries, fur trappers, American Indians, and others ventured repeatedly into and across the vast territory between New Mexico and California.

By the time Armijo started his trip, New Mexican traders were familiar with the routes others had followed and utilized the cumulative geographic knowledge gained from previous expeditions.

The trips were arduous. Dramatically changing terrain and climate posed major challenges. Caravans lost their way, suffered from thirst, and were forced to eat some of their pack mules when supplies ran out. Animals also suffered in the harsh desert environment and endured severe weather.

Commerce along the Old Spanish Trail began as a legitimate barter for horses and mules, but some traders and adventurers found it easier to steal livestock than to obtain it legally. Americans claiming to be beaver trappers, fugitive Indians from the missions, gentile Indians from the frontier, and renegade New Mexicans teamed together to gather horses and mules to take illegally back to New Mexico. In reaction to these widespread raids, California authorities tried to recapture the stock and punish the thieves but were never able to control the illicit trade.

The line of march of this strange cavalcade occupied an extent of more than a mile...Near this motley crowd we sojourned for one night...Their pack-saddles and bales had been taken off and carefully piled, so as not only to protect them from damp, but to form a sort of barricade or fort for their owner. From one side to the other of these little corrals of goods a Mexican blanket was stretched, under which the trader lay smoking his cigarrito...

—Lieutenant George Brewerton, 1848

Packing the Train

Along the Old Spanish Trail sound animals, good packing equipment, and a capable crew were the prerequisites of a successful pack train. The success of the trip depended on the skills and abilities of those who packed and drove the animals that carried the merchandise.

New Mexicans had a well-deserved reputation as excellent horsemen and muleteers. American eyewitnesses marveled at the dexterity and skill with which they harnessed and adjusted packs of merchandise. Experienced travelers suggested that New Mexicans should always be used as teamsters for they "can catch up and roll up in half the time the average person does."

Packers were always in demand and utilized a variety of skills. They secured loads with intricate knots, splices, and hitches; they acted as veterinarians and blacksmiths. They estimated the safe carrying capacity of a mule, and identified and treated animals suffering from improperly balanced loads. They timed the travel day to stop at a meadow or creek bottom that provided good forage. Packers also had to be able to lift heavy loads, be good farriers, and "accomplish marvels with the axe and screw key and a young sapling for a lever."

Beasts of Burden

Mules had incredible strength and endurance, fared better than horses where water was scarce and forage poor, and recovered, more rapidly after periods of hardship. Their hard and small hoofs withstood the shock and abrasion of rocky, boulder-strewn terrain.

The Equipment

While the mule was the heart of the transportation system, the packing equipment played an equally significant role. The aparejo (packsaddle) was the central piece of gear and carried heavy, odd-sized items safely over long distances without injuring the animal. It was described by one observer as "nearer to what I consider perfection in a pack saddle, than any other form of pack saddle yet invented."

Witness

Illegal Captivity

Long before traders ventured into this region, American Indians traveled and traded along many of the paths that the trade caravans later followed. Petroglyphs show us that the mule caravans were witnessed by American Indians along the route. Indian guides had lengthy contact with Mexican and American traders.

Trade sometimes involved the illegal exchange of horses, mules, and even human beings. Some captives, including American Indians, Spaniards, and Mexicans, were ransomed at the frequent trade fairs that characterized the western economy. The slave trade changed the lifeways of American Indians through depopulation and loss of traditional knowledge. Human captivity was part of the reality of the West, affecting all who lived in the region.

The Railroad and the End of the Trail

Beginning in the mid-1840s, new routes such as wagon roads carried troops fighting in the Mexican-American War, pioneers bound for California, miners joining the gold rush, and still more traders into the West. A few notable Americans used the trail. In 1847 and 1848, Kit Carson carried military dispatches east along the Old Spanish Trail. Military attaché George Brewerton kept a detailed account of his trip. John C. Fremont led U.S. government-sponsored exploratory survey trips to plan for the advent of railroads in the West.

By 1869, however, a rail route connected the plains of the Midwest and San Francisco Bay. Portions of the Old Spanish Trail evolved into wagon roads for local travel, but the days of cross-country mule caravans on the Old Spanish Trail had ended.

Exploring the Trail

Timeline

EARLY EXPLORATIONS | |

1598 |

Don Juan de Oñate establishes San Juan de los

Caballeros (near modern Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo), the first Spanish

settlement in New Mexico. |

1610 |

Don Pedro de Peralta founds Santa Fe, the new

capital of New Mexico. |

1765 |

Juan Maria Antonio Rivera leads two parties

from New Mexico to explore southwestern Colorado and southeastern

Utah. |

1774 |

Father Francisco Hermenegildo Garces sets out

from southern Arizona to explore a path to the California missions. He

follows the Mojave River and reaches Mission San Gabriel. |

1776 |

Franciscan priests, Francisco Atanasio

Dominguez and Francisco Silvestre Velez de Escalante follow Rivera's

route to the Great Basin in western Utah. |

1781 |

Spanish colonials establish El Pueblo de la

Reina de los Angeles in California. |

1821 |

Mexico gains independence from Spain. |

1825 |

Antoine Robidoux builds Fort Uncompahgre

(Fort Robidoux) near present-day Delta, Colorado, where Indians and

traders bargained for goods. |

1826 |

Jedediah S. Smith leads a small party of fur

trappers westward from Cache Valley, Utah. |

TRAIL MILESTONES | |

1829 |

Antonio Armijo leads the first trade caravan

from Abiquiu to Los Angeles, opening the Old Spanish

Trail. |

1831 |

William Wolfskill and George C. Yount blaze a

more northern route that ascends into central Utah before heading

southwest into California. |

1834 |

José Avieta and 125 men arrive at Los Angeles

carrying 1,645 serapes, 314 blankets, and other woolen

goods. |

1837 |

José María Chávez and family settle in what became

known as the Chávez Ravine in Los Angeles. |

1839 |

José Antonio Salazar arrives in California at

the head of a group of 75 men; Francisco Quintana carries domestic

manufactures worth $78.25. |

1841 |

Francisco Estevan Vigil arrives at Los

Angeles and presents a passport and instructions describing the duties

and responsibilities of a commander of a caravan. |

1842 |

A party of 40 New Mexicans from Abiquiu

settles at Agua Mansa and Politana in California; Francisco Estevan

Vigil and 194 men are issued passports carrying 4,150 California animals

back to New Mexico. |

1843 |

Juin Arce hauls merchandise worth $487.50. |

1844 |

Francisco Rael carries domestic manufactures

and sheep worth $1,748. |

1846 |

The Mexican-American War begins. |

1848 |

Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo ends

Mexican-American War; the Southwest becomes U.S. territory; California

Gold Rush begins. |

1849 |

Commercial caravans across the Old Spanish

Trail largely cease as more direct transportation routes

develop. |

2002 |

The Old Spanish National Historic Trail is

designated by Congress. |

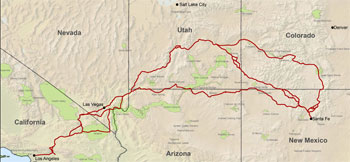

Three Trails

Three trails, including the Old Spanish Trail, merged in Santa Fe. El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro (the Royal Road to the Interior Lands) was a wagon road between Mexico City and Santa Fe. The Santa Fe Trail, an international wagon route that crossed the plains, linked Missouri with Santa Fe.

The trails witnessed dramatic growth in use after 1821, when a large and broad array of merchandise came to New Mexico from the Eastern United States and Europe. Merchants took many of these products further into Mexico along El Camino Real de Tierra Adentro.

Old Spanish Trail Travel

The Old Spanish Trail's rugged terrain discouraged the use of wagons. It was always a pack route, mainly used by men and mules.

Traders used different routes from trip to trip, depending on weather and water. Caravans left New Mexico in the late summer or fall and returned from California in the spring. Early winter snows blocked mountain passes and travelers chose their routes accordingly. In the spring, traders worried about late snows and floods. On every trip, they worried about water and forage, often racing to beat other caravans to known sources.

All routes came together at Fork of Roads, east of present-day Barstowjin the Mojave desert, and then crossed Cajon Pass between the San Gabriel and San Bernadino Mountains to Coastal California. After negotiating the pass, traders had an easy two to three days travel to the San Gabriel Mission and beyond to Los Angeles.

The Northern Route:

First blazed by William Wolfskill and George C. Yount in 1831, this

route veered northwest from Abiquiu through Southern Colorado and

central Utah. It avoided the rugged canyons of the Colorado River that

the Armijo party had encountered and took advantage of the better water

and pasture resources across central Utah before returning to the

Colorado River and Armijo's route not far from Las Vegas.

The Mojave Road:

A 188-mile crossing of the Mojave Desert long used by area Indians and

by Spanish explorers and missionaries, it was first traveled by Jedediah

Smith, an American trapper, in 1826.

The North Branch:

This route followed well-known trapper and trade routes north through

the Rio Grande gorge to Taos and into southern Colorado. It then went

west through Cochetopa Pass, largely open during the winter when other

passes were snowed in and up the Gunnison River valley, rejoining the

Northern Route near present-day Green River, Utah.

The Armijo Route:

The first complete trip across the trail began in Abiquiu, northwest of

Santa Fe. The Armijo party followed well-known trails northwest to the

San Juan River, then nearly due west to the Virgin River They used the

Crossing of the Fathers, cut into rock canyon wall some 75 years earlier

by the Dominguez-Escalante party. Armijo's caravan went down the Muddy

River and across the Mojave Desert to the Amargosa and Mojave Rivers,

through Cajon Pass and down to Mission San Gabriel.

(click for larger map) |

Explore Today

It is difficult to see traces of the trail in the modern landscape. Most of the routes of the Old Spanish Trail have been reclaimed by nature or changed by later use. However, some of the landmarks that guided trail travelers can still be seen today.

The following sites along the trail offer the opportunity to experience some of the natural landscapes crossed by the trail. They are only a small sampling of places you can visit associated with the trail. You can learn more by visiting the official trail websites.

Arizona:

• Glen Canyon National Recreation Area

• Grand Canyon/Parashant National Monument

• Navajo National Monument

• Pipe Spring National Monument

California:

• Desert Discovery Center, Barstow

• El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument

• Mission San Gabriel, San Gabriel

• Mojave National Preserve

• Mojave River Valley Museum, Barstow

• San Bernardino County Museum, Redlands

Colorado:

• Anasazi Heritage Center/Canyons of the Ancients National Monument

• Colorado National Monument

• Curecanti National Recreation Area

• Dominguez-Escalante National Conservation Area

• Fort Garland Museum, Fort Garland

• Fort Uncompaghre, Delta

• Great Sand Dunes National Park & Preserve

• Gunnison Gorge National Conservation Area

• McInnis Canyons National Conservation Area

• Southern Ute Cultural Center and Museum, Ignacio

• Ute Museum and Memorial Site, Montrose

Nevada:

• Lake Mead National Recreation Area

• Lost City Museum, Overton

• Old Las Vegas Mormon Fort State Park

• Red Rock Canyon National Conservation Area

• Springs Preserve, Las Vegas

New Mexico:

• Aztec Ruins National Monument

• Palace of the Governors and New Mexico History Museum, Santa Fe

• Rio Grande Gorge Visitor Center, Taos

• Spanish Colonial Art Museum, Santa Fe

Utah:

• Arches National Park

• Beaver Wash Dam National Conservation Area

• Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument

• John Wesley Powell River History Museum, Green River

• Museum of the San Rafael, Castle Dale

• Dan O'Leary Museum, Moab

• Iron Mission State Park, Cedar City

Trail Administration

The Old Spanish National Historic Trail was designated by Congress in 2002. The trail runs through New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and California. The Bureau of Land Management and the National Park Service administer the trail together to encourage preservation and public use.

These two federal agencies work in close partnership with the Old Spanish Trail Association, American Indian tribes, state, county, and municipal governmental agencies, private landowners, nonprofit groups, and many others.

For more information, including more site locations and trip planning tools, please visit our official trail websites:

Bureau of Land Management

Utah State Office

www.blm.gov/ut

National Park Service

National Trails Intermountain Region

www.nps.gov/olsp

Volunteer Organization

Old Spanish Trail Association

www.oldspanishtrail.org

Source: NPS Brochure (2012)

|

Establishment Old Spanish National Historic Trail — December 4, 2002 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

American Indians and the Old Spanish Trail (Richard W. Stoffle, Kathleen A. Van Vlack, Rebecca S. Toupal, Sean M. O'Meara, Jessica L. Medwied-Savage, Henry F. Dobyns and Richard W. Arnold, December 19, 2008)

Comprehensive Administrative Strategy, Old Spanish National Historic Trail (December 2017)

Ethnohistoric and Ethnographic Assessment of Contemporary Communities along the Old Spanish Trail (Richard W. Stoffle, Rebecca S. Toupal, Jessica L. Medwied-Savage, Sean M. O'Meara, Kathleen A. Van Vlack, Henry F. Dobyns and Heather Fauland, December 19, 2008)

Final Comprehensive Administrative Strategy, Old Spanish National Historic Trail (2016)

Federal Land Ownership Maps, Old Spanish National Historic Trail: AZ • CA • CO • NM • NV • UT

Junior Ranger Program, Old Spanish National Historic Trail (2020; for reference purposes only)

Map, Old Spanish National Historic Trail (2009)

Maps, Old Spanish National Historic Trail (2006)

National Historic Trail Feasibility Study and Environmental Assessment, Old Spanish Trail Draft (July 2000)

National Historic Trail Feasibility Study and Environmental Assessment, Old Spanish Trail (July 2001)

Recreation and Development Strategy

Emery County, Utah (March 2017)

Grand County, Utah (March 2018)

Iron County, Utah (October 2014)

Mesa and Delta Counties, Colorado (October 2018)

San Bernardino & Inyo Counties, California (September 2015)

olsp/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025