|

OREGON'S HIGHWAY PARK SYSTEM: 1921-1989 An Administrative History |

|

DEVELOPMENT OF THE STATE PARKS AND RECREATION PROGRAM 1962-1989: A PERSONAL VIEW (continued)

II. Parks and Recreation programs

When you reflect on the number of programs external to traditional state park operations that developed during the 1960s, what do you think these Programs have contributed to the quality of life for Oregonians?

Outdoor Recreation

I think the programs that are to some degree "external" have contributed in many ways. First on the list is the Statewide Outdoor Recreation program, which is supported by the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act passed by Congress in 1964 to provide federal aid for parks and recreation. It was launched as one of a number of natural resources and environmental protection programs making up President Johnson's "Great Society" agenda, but the enabling legislation stemmed from recommendations of the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission (ORRRC), a federal body originally set up during the Eisenhower administration and headed by Laurence Rockefeller, the long-time chairman. The commission did an exhaustive study of the condition of outdoor recreation in America, and found there was much that needed to be done and there was little money to do it at the federal, state or local level. So the Land and Water Conservation Fund was created, largely supported by revenue from Off-shore oil leases. At that time I was in the position of state recreation director and it fell to me to put together the first Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (SCORP) for Oregon. A Statewide recreation plan was requisite to getting the federal money. Coincidentally, in 1962, State Parks had released a comprehensive plan that showed who was meeting recreation needs around the state and how the responsibility could be better allocated in the future. What surprised a lot of people was that the federal agencies, which controlled most of the suitable areas, were not providing opportunities in proportion to their land base. The plan was handsomely designed under Superintendent Astrup's direct Supervision and created quite a stir of favorable comment. It was the first long-range master plan for outdoor recreation in Oregon. The study group had been directed by Dick Dunlap and Dick McCosh, who headed the Parks advanced planning unit consecutively. We negotiated with the federal government through its Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, Seattle office, to accept a revised and expanded version of Oregon Outdoor Recreation: A Study of Non-Urban Areas. The state's watershed recreation study, that important legacy of Mark Astrup's administration, meant that we didn't have to start over from scratch.

Oregon Outdoor Recreation. Part II, Local Government and the Private Sector was completed in 1964 as a complement to the basic outdoor recreation plan of 1962. Ours was one of the first comprehensive outdoor recreation plans approved under the federal aid program. The matching funds were released not only to State Parks, but were passed through to cities and counties as well. Despite our success, it was then I realized I wasn't a planner. It was a difficult process to assemble all that data, make some sense out of it and meet the rigorous standards of the federal government. Bureau of Outdoor Recreation officials also were learning in the course of setting up a new program, and there was a lot of anguish over what the SCORP ought to be.

It was interesting, trying to get a grip on what was needed. The theory was that the states would assess the situation, determine the needs and how to meet the demand. On a practical level, it broke down because of politics. Portland and Eugene, the two major population centers, had developed recreation facilities early on. When the real need is in West Linn in Clackamas County, for example, and the money is allocated there rather than Portland or Eugene, that is not going to fly, politically. Trying to get local governments to agree on the standards is a challenge. How many parks are enough? Each jurisdiction wants to make its own determination. Corvallis will decide what's good for Corvallis. Years later, we made an attempt to resolve the issue of overall coordination. Oregon's Recreation Delivery System was prepared by James M. Montgomery Consulting Engineers, Inc., of Portland in 1980. I sent State Recreation Director Kathryn Straton around the state in an attempt to gauge the feeling of parks and recreation professionals for statewide coordination of recreation planning. The concept was not well accepted.

Another feature of this program was national coordination. A nationwide meeting of state-level administrators of the program was called in 1965 at Illinois Beach State Park on Lake Michigan. Ed Crafts, formerly with the U. S. Forest Service, was the first director of the new Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. There he assembled all the liaison officers who had been appointed to run the program, which was to be decentralized to the states. The Secretary of the Interior had written to each of the governors and asked, "Who do you want to coordinate this Land and Water Conservation Fund program?" Each governor delegated responsibility to a state liaison officer. I carry that title today. I went to the first meeting of all those people from around the nation, and I can remember I was so excited flying to Chicago. Here I was going to meet with the brains of the country in the recreation field. We were going to discuss things that were important to the future of America. Boy, was I sadly disillusioned. When they handed out that sheet of paper that listed all the state allocations, the delegates went straight down the column to see how much money their state got, and that was all they could focus on. Driving back to the airport, a fellow from Illinois State Parks told me a ward boss decides who hires the park ranger in that area. I was really disappointed to realize it wasn't all sweetness and light.

The Land and Water Conservation Fund has been very important to Oregon. It was a major factor in establishing the Willamette River Greenway. We secured something close to $5 million from the Land and Water Conservation Fund contingency reserve at the Secretary of the Interior's discretion because of the nationwide attention the Willamette Greenway was getting as a model program.

It also brought playgrounds to Oregon communities. We mirrored the federal system. When the money started coming down, the question was, "How are you going to give it out?" My answer was, "We'll do the same thing the Feds do." People in Lane County probably know what's needed there better than anybody in Salem. We simply adopted a formula, the same formula the Feds had; we created county liaison officers, and we required them to bring all the local jurisdictions together on a regular basis to discuss what was best for Lane County or whatever county it was. That worked very well for many years until the Carter administration took over. Instead of a lot of small, unglamorous projects, the Carter people wanted to have some pizzazz, more impact on a broader scale with fewer projects. They forced us out of the formula business into another approach which we are using today and which works equally well. It's a process whereby you develop goals and objectives in the SCORP and, in theory, those are the criteria you use in doling out the money. You look at those issues, whether it's stream access or urban parks, and allocate accordingly.

As the program went along, the decentralized approach started to lose its political appeal. As that pot of pass-through money went down, the proportion of money going to federally sponsored recreational development went up. The National Park Service, the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management were getting more and more of the money. Then, private advocacy groups began to develop. The purpose of groups such as the Trust for Public Lands and the Nature Conservancy is to acquire and protect lands. They are in there dealing with the Congressional appropriations committees on parks as private sector entities, and they do it very successfully.

It can be very appealing to our Congressional delegates to buy a valley on Steens Mountain. They can see it. They can go out, walk in it and feel good about it, as compared to building the playground in Yoncalla, which they may never see unless we arrange for them to be there. Arrangements of that kind weren't handled very well at the state level. So the action shifted to the federal agencies. The advocacy groups tended to pick a piece of land, buy it without checking with the Forest Service, then go to Congress to get the money into the Forest Service budget so the group could be reimbursed for the acquisition. I always have had trouble with that. They gave State Parks that treatment once. They tried to end-run me with some property they purchased in the Columbia Gorge for which they thought the state should reimburse them. They still own the land. I had worked with them before and was on good terms with them, but when they did that, I said, "You can't do that to me. If we want to work out an arrangement in advance, and you carry it out, then I'll break my back to reimburse you. But if you do it on the front end, that doesn't make any sense. That's not good public policy." On the other hand, if you look at the bureaucratic approach to acquiring land for the public domain, whether it's Redwood National Park or whatever, it isn't always as efficient. It can be fraught with condemnation proceedings.

That is only part of the story of how the Land and Water program evolved. Early in the Reagan years, it was foreseen that the Land and Water Conservation Fund would be phased out, and people tried to get another Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission formed. Congress wouldn't do it. That spelled the program's doom to me. The President's Commission on Americans Outdoors traveled for a year or more all over the country before they put out a report. The problem, from my perspective, was that they weren't able to do the groundwork that ORRRC had done to show clearly there was a need and what the problems were. As the Americans Outdoors Commission went around, what they heard was, "We surely have enjoyed spending your money and we want you to continue." Nobody really made the argument that America needed to spend federal money in Yoncalla, Oregon. I think it is the fundamental matter of justifying expenditure of federal tax dollars on local projects that is the key to the program's revitalization.

Willamette River Greenway

On the subject of the Willamette River Greenway, I'll start with a personal anecdote. I was flying up the Willamette Valley in a Pacific Power and Light Company airplane with Highway Commission Chairman Glenn Jackson. (In professional life, Glenn was chairman of the board of PP&L.) We were going to Eugene to meet Lane County Parks Superintendent Paul Beistel. I turned to Glenn and said, "Next to the ocean beaches and the Cascade Mountains over here, this is probably the most important recreation resource in Oregon." He said, "Oh?" He sucked on his pipe, and up the valley we flew. Coincidentally, 1966 gubernatorial candidate and State Treasurer Bob Straub was in Portland announcing at a news conference one of the key issues of his campaign was "rediscovery" of the Willamette River. He had a visionary idea to create a park, or continuous greenbelt on either side of the river, complete with bicycle trails you could ride from Eugene to Portland. People thought it was a great idea. His opponent was Secretary of State Tom McCall, who turned around and said "Bob, that's a great idea. If I am elected governor I'm going to do it better than you could." McCall was elected, and, lo and behold, I found myself in the secretary of state's office with Glenn Jackson. Tom McCall said, "Glenn, what am I going to do? I got what I asked for, now how do I get there?" As the new governor coming in, and with the legislature convening in less than three months, he would be expected to come forward with a program. Glenn said "Well, that's simple, Tom. You've got to have a plan. Dave, put a plan together."

We secured the services of a volunteer team of recreation specialists that included Pacific Power and Light Company recreation planner Larry Espey, Oregon State University recreation specialist Merv Filippoini, Lane County Parks Superintendent Paul Beistel, County Parks Association president Charles Collins, Eugene attorney Orval Etter, and Tony Kom of the University of Oregon Bureau of Governmental Research and Service. We called, and they came. They left their jobs, lived in Salem and did a crash plan. The team, known as the Willamette Greenway Task Force, went out on the river and drew boundaries where they thought a greenway should be. They got that ready for the 1967 session. An important policy call occurred in the middle of this. As it turned out, there was a three-to-three split on the task force over a fundamental question. Was this to be a state program or a local program? The local people had been doing things for years. Eugene had done a great job with its riverfront. Albany, too, to some extent. Portland, no. So there was a debate. "If you leave it to local government, you're not going to get as much accomplished. It has got to have some real push behind it." Even so, Ed Westerdahl, the governor's chief of staff, could foresee political problems arising from a massive state initiative getting crosswise with the agricultural community. He settled the debate and said this should be a local program.

I can remember jumping on a bus with legislators to drive around and look at the Willamette. After the bill authorizing a Willamette River Park System was passed by the Oregon Legislative Assembly in 1967, Governor McCall convened all the mayors and the county commissioners and said, "Let's get going with this." We had a lot of cheerleading, and we had some wonderful boat trips. On one of them, I had a fishing contest with the governor. He beat me at the Springfield Bridge as we were pulling out. We got a lot of publicity over the Willamette Greenway. The object was to stimulate local government to take action. A lot of good things happened.

As the story unfolded, Tom McCall was coming up for reelection. Bob Straub sniped at him occasionally, saying, "Hey, Tom. How's my greenway?" The phone was ringing, and we were constantly reporting to the Governor's Greenway Committee, of which Glenn Jackson was a member. The chairman was C. Howard Lane. The eleven-member advisory panel, initially known as the Governor's Willamette River Park System Committee, was to ride herd on greenway development. We were able to get George Churchill, a retired U. S. Forest Service official, to head greenway operations for us. We were fortunate to have him. But by the time Governor McCall's second term came around, local governments were running out of the easy acquisition projects and progress was slowing down. Glenn said, "Okay. Go out and find a state park in each county." So we sent out the staff under the direction of chief planner Larry Jacobson. They came back and said, "The flood plain is a tough place to develop parks." You've got to get up on higher ground, which usually meant farm land. They also said a park wasn't needed in each county. They had located five areas that would cover the needs on a regional basis. At that point, we were crossing over the line into serious state involvement. We convened a meeting of the county commissioners and said, "We are about to move on this, for your information. Just so you are aware. And they all said "Okay. Here we go." We had targeted recreation areas below Dexter Dam on the Middle Fork (Elijah Bristow), Mt. Pisgah on the Coast Fork, Bowers Rocks between Albany and Corvallis, Willamette Mission near Wheatland, and the mouth of the Molalla River. We made a start on those. But overall, things weren't moving fast enough.

Somebody said we ought to get money from the Secretary of the Interior's contingency fund to stimulate the program. Bob Wilder, the state recreation director, and I didn't think the program would qualify. But I was on Sauvie Island one day when a state policeman pulled me over. I couldn't imagine what I had done wrong. He said, "Call your office." As it turned out, L. B. Day, who was at the time Interior Secretary Stewart Udall's liaison in Oregon, had been instrumental in securing $5 million from the Secretary's contingency fund. I was to get myself to Washington, D.C., as fast as I could to facilitate the paperwork, news releases and other formalities. I dropped everything, jumped on the airplane and arrived in the nation's capital. There, in his office, with the cameras whirring, Secretary Udall announced to America that he wanted to help the exemplary Willamette River park system out in Oregon. Suddenly, new life was pumped into the program.

Even with federal assistance coming through the pipeline, Bob Straub continued to prod. "What is being done for the greenway?" At a meeting in Portland, Mr. Jackson said the demand for money from local government had dried up almost entirely. The cities and counties had exhausted their prospects for acquisition and development. The number of riverfront miles being added to the system had come to a standstill. At that point we created the concept of corridor lands. Lands would be purchased not necessarily for recreation purposes, but to provide a scenic corridor along the river. Out went an army of Highway right-of-way agents. There must have been 20 or 30. Then, a team began talking to farmers about selling their land. Consider the farmer whose riverbank acreage is sloughing into the Willamette. He is likely to say to the agent, "Sure, I'll sell my eroding property that's not going to be here next week." We started picking up property like that rapidly, large chunks of it. Most of it is out there today. It is "in the bank," so to speak.

Initial success with willing sellers ran its course, and at a later meeting, when I should have jumped up and screamed, "No, Glenn!" Mr. Jackson said, "I guess we're going to have to resort to condemnation if we are going to get this program accomplished." It didn't take long before the farmers' lobby was effective in getting Mr. Jackson and me hauled before the Legislative Emergency Board, whereupon all the money was taken out of the greenway budget, and the Emergency Board unceremoniously said "Until this matter is cleared up in the next session, that's the end of it." Things did not get back on track until 1975 when the Willamette River Greenway program was redefined in law as a cooperative effort of state and local government to protect the river corridor.

While the legislature reevaluated the greenway law, we defended ourselves as best we could. We were digging out. We were really in a hole over the condemnation issue, even though we hadn't condemned a thing. There was concern over the possibility of it. During this period we put together another plan and spent a fortune doing it. We hired a top flight public relations firm from San Francisco. We went out, settled all the people down, and had everybody in general agreement, when Bob Straub succeeded in winning election as governor in 1974. One of the first things on the governor's agenda was the greenway, the concept of which he had done so much to define in his campaign eight years earlier. At his interim office soon after the election, he urged me to pursue the program. "Get out there and get on with it," he said. So we revved her up again, and the world caved in around us.

The Land Conservation and Development Commission was newly formed at this time under authority of state law. Once the statewide planning goals and regulations were the place, the greenway program ceased being a land purchase program and moved into the area of land use planning, where it remains today.

The Willamette River is very important to the future of Oregon, in my opinion. It is the thread that connects the major centers of population. Nobody seems to want to talk about that bicycle path from Eugene to Portland anymore. Instead, people seem to be fairly comfortable with a number of parks and scenic protection along the river, but not necessarily a fully-connected system. I am an old-fashioned park person. I want to connect those features and make the system continuous. I want to do as much of that as we can so people can enjoy protected scenery along all 255 miles of the recreation corridor. The corridor lands are a real asset, but I think the uplands are valuable too. The 1991-1993 budget proposed a million dollars to revive the greenway plan. To give it the best chance, one approach would be to allocate half of that money to local government. The farmers have their ways of influencing cities and counties, and I think they would be comfortable with that. Possibly the state would limit its acquisition to lands available from willing sellers.

As for state greenway acquisition to date, we bought some very expensive property. We acquired the Willamette Mission State Park through the power of eminent domain. Condemned it, in other words. The rest of the five parks we targeted are operating but not complete. Mt. Pisgah is secured and managed by Lane County. There lies another story. Somebody came to us and said, "You ought to buy Mt. Pisgah. It's a good property." So I found myself at Stub Stewart's house in the shadow of the mountain near the junction of the Coast and Middle forks of the Willamette. We got in his helicopter and went to the mountain top and looked around. The place was laced with power lines. It is not the most scenic place in the world. We came back and said we chose not to acquire it. Paul Beistel, Lane County parks superintendent, wasn't satisfied with that. He went out and took wonderful pictures of birds and wildflowers, hauled them up in front of Governor McCall, and bedazzled him with the wonders of Mt. Pisgah. The governor called on the phone and said, "What's wrong with you, Talbot? You ought to do this." I said, "Yes, sir," and we bought Mt. Pisgah. After the dust settled, years later, we deeded the holding to Lane County, so it could be managed locally. Today it is known as Buford Recreation Area. The arrangement works just fine.

America is falling in love with greenways today. All across the country, people are talking about the concept. They may have forgotten that there is an early model in western Oregon. There is a plan sitting on our shelves that says which piece of land ought to be purchased and why. It should be updated.

The Willamette River was one of Tom McCall's first successful causes as governor. He had been a broadcast journalist in Portland, and when he took on the Willamette's clean-up, a big project, he gave it a lot of public exposure. The newly created Department of Environmental Quality worked to get local water and sewer districts, farmers, canneries and industrial plants to reduce the harmful effluent. My wife, Ann, grew up in Eugene in the 1930s and '40s when the river was posted. You couldn't go near it, it was so polluted. Revitalization of the river was a major factor in gathering support for the greenway program.

The program has been a popular success. Drive through downtown Portland on any weekend when the weather is decent, and you will find the reclaimed riverfront alive with people. The same is true in waterfront parks from one end of the greenway to the other. People are using the river for recreation. I think the Willamette River, as a long-term investment for outdoor recreation, is outstanding.

Historic Preservation

I always have enjoyed Oregon history, and I'm fascinated by the story of the state's development. There were some historic properties in the parks system when I walked in. The major study of historic and commemorative events at Champoeg State Park, prepared on contract by National Park Service historian John Hussey, had just been completed in 1962. Eventually, it was published for a wider audience. I felt the well-rounded park system of the future had to have a heavier infusion of cultural and historical attractions. One of the first assignments Parks Superintendent Harold Schick gave me when I came in as recreation director was to accompany Tom Vaughan, then executive director of the Oregon Historical Society, on a mission to the Old Yaquina Bay Lighthouse at Newport. The lighthouse was a long unused feature in Yaquina Bay State Park that was in poor repair and scheduled for removal. Mr. Schick wanted to know if we thought that was a good idea. So we went down and took a look and came back and said, "No. We should not tear it down." I have always felt good about that, because our lighthouses are such a colorful aspect of our coastal heritage and scenery. I took over as superintendent with the intent of rounding out the system with historical projects to the best of our ability.

We found ourselves playing defense with people who were very knowledgeable in the business. We were amateurs dealing with people who wanted us to do this, or not do that. I felt we needed some expertise on the staff, so we hired a park historian to help us evaluate the properties we were encouraged to take on. Looking back, I regret letting the lighthouse keepers' houses at Cape Meares be torn down in 1968, deteriorated as they were. I had good advice on both sides of the issue. I'd choose differently today.

Historic preservation gained national prominence with passage of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. The act authorized a federal aid program that was patterned after the Land and Water Conservation Fund program, using the same revenue source of off-shore oil leases. Once again, the Secretary of the Interior wrote the governors asking, "Who do you want to handle this program in your state? There is money, but there also are strings." It turned out State Parks enabling statutes encompassed the acquisition and management of historic property, whereas no other state agency's did, other than the State Board of Higher Education. The Oregon Historical Society probably would have liked to have been given responsibility for the program, but it is not, strictly speaking, a public agency, even though it is funded in part by legislative appropriation.

In any case, management of the statewide program for historic preservation was assigned to our shop. We had to meet federal requirements for professional staff and various experts on the Advisory Committee on Historic Preservation. Those were the days of State Recreation Director Walt McCallum, who instituted the scoring sheet for nominations to the National Register of Historic Places. The rating sheets were useful in the initial debates over what is important in Oregon culture, history, architecture and archaeology. You might think, casually, the National Register of Historic Places would have enrolled in it only properties of national significance. Not so. It took me some time to recognize that properties of state and local significance were eligible for enrollment too. Sites and buildings of importance to Oregon communities are as significant as Ford's Theater in Washington, D.C., in the point of view of the National Park Service, which runs the program at the federal level.

Every National Register nomination has to go before the Advisory Committee on Historic Preservation and be blessed. It is the committee's main purpose to act as quality control for the National Register. While the committee's advice has influenced policy over the years, its role is advisory, rather than managerial. The panel has worked hard and has been very effective, and Oregon is richer for the state-coordinated historic preservation program. The program has promoted restoration of historic buildings in Jacksonville, Astoria and Baker City. Cities and counties have caused inventories to be made and people have nominated thousands of properties to the National Register, counting the ones in historic districts. Incentives offered by provisions of the Economic Recovery Tax Act and Oregon's historic property tax law have combined to make things happen. That is not to say important buildings have not been destroyed, but hundreds have been preserved and restored.

A number of communities are aware of the assets they have in historic downtowns and neighborhoods. I think of Jacksonville and the champion of that former gold mining town, Robertson Collins. In such towns, promoting the past has come to be "bread and butter," and that approach to economic vitality is being more widely applied as time goes on. Too, there is constant watchfulness on the issue of quality. "Why do we put this ordinary bungalow on the National Register?" The question is debated continually. Each of the nominations is reviewed on its own merits, and the Advisory Committee on Historic Preservation makes its determinations according to criteria established in federal rules and guidelines. Some members are more conservative than others. It has been very interesting to watch the trends ebb and flow over time. I feel strongly the program has been a positive force in Oregon.

Archaeological preservation is a different problem. I don't know how we will ever get it fixed to everyone's satisfaction. Oregon is one giant archaeological site. In some areas, you hardly can turn around without bumping into a lithic scatter, occupation, burial or sacred site of some kind. Today, thanks to professional education and the work of heritage consultants, the number of people who understand and appreciate Native American culture and respect its traditional values is increasing. But there is that segment of the population that won't observe the rules, that will loot a well-known site at the expense of everyone. Wisely, the Native American Indian community has pressed for legislation to limit conditions under which prehistoric sites can be investigated and have seen to it that rules have been adopted to govern the disposition of artifacts disturbed accidentally in the course of construction. We don't present enough information to our park visitors about the people who lived here before we did, and that's a shame. I look for opportunities to do something about that.

When the federally-funded historic preservation program came along in the late 1960s, our professional historians became absorbed in it full time. Nevertheless, through efforts of the field organization, for many years headed by Deputy Parks Superintendent Warren Gaskill, and with the cooperation of the history staff and citizen activists, strides were made in interpretive work at Fort Stevens, Yaquina Bay and Champoeg. Historical waysides such as the Kam Wah Chung Building at John Day and the Wolf Creek Tavern were added to the system, as was the Patrick Hughes House at Cape Blanco. Today we are embarked on development of our latest historical acquisition, the site of Fort Yamhill. We have identified the need, and are trying to budget for a full-time historical coordinator for Parks to help those developments along.

Beach Access

Ocean Shores Access is another valuable program. A lot has been written on the subject, but I want to discuss some aspects of it. As I was getting started in State Parks during Governor Hatfield's tenure, the governor's assistant for Natural Resources was Dan Allen. Dan was successful in getting a bill through the legislature changing the classification of beaches and tidelands from "public highway" to "state recreation area." That occurred in 1965. Suddenly, we were in charge of a vast coastal recreation area. I started to look into what it was we had just inherited. The more I learned, the more concerned I became. I found memos from former Highway Chief Counsel Joe Devers and others suggesting the title issue was complicated.

Shortly after I took over as superintendent, I received a letter from John Yeon congratulating me. Almost as an aside, he said, "Oh, and by the way, be sure and look into the myth of public beaches." This encouraged me to go further. I finally picked up all the data and carried it down to Assistant Highway Engineer Lloyd Shaw. We took it to Portland and sat down with Glenn Jackson. He said "You'd better get ready for the legislature." The State Parks and Recreation Advisory Committee agreed. They said, "We've got to get the ambiguities resolved." So we raced to the Highway attorneys and asked them to write a bill for the 1967 legislative session. Highway Commission Chief Counsel George Rohde, his assistant, Frank McKinney, and title attorney Jim Kuhn set to work and found legal precedent for open beaches in Texas and a few other places. They drafted legislation based on the common law doctrine of implied dedication. To explain, a property may be privately owned, but if the public has used a part of it for a long time, you can't keep them out. They have established an access easement, in theory. Oregon's beach bill was drafted on the same principle. We presented it to the legislature in 1967. I still can remember Stan Ouderkirk, who represented Lincoln County in the House at that time, getting madder than heck at first and saying, "Look, we just changed the tidelands classification in the last session from highway to recreation area, and here you are coming in with a big land grab for the dry sands."

The battle was on, and the issue was private property rights versus public access. Most people had no real concept of who owned the beach in the dry sands area above the line of ordinary high tide. Property owners didn't want the state managing development of their beachfront property and the public didn't want to be barred from the areas they had used for generations. I began testifying on behalf of the proposed beach legislation before the 1967 legislative assembly without much success. Because of the strong feeling for private property rights, I was getting hardly any support. Then, the controversy sparked by William Hay, a motel owner at Cannon Beach, exploded. Mr. Hay understood exactly how far his beachfront property line extended. He went out one day and started driving piling to fence off his area of the sandy beach for the convenience of his guests. It couldn't have happened at a better time. The public said, "You can't let this happen!" They began to pay attention. The fenceline made things graphic. The press photographed it and sent those pictures everywhere. We went to California and photographed Santa Monica, where everything is built right out onto the beach. The potential for intensive development was what we were trying to show people. "Is this what you want your beaches to look like in 50 years?"

After the beach bill was signed into law early in July, 1967, any development seaward of 16 feet of elevation required a permit from the state Highway engineer. Mr. Hay did not want to remove his barrier, and the case went to trial in Circuit Court in Clatsop County with Frank McKinney as lead counsel for the state. We had to get evidence to support the argument that the beach traditionally was in public use, and we were preparing to do it on a case-by-case basis. At South Beach, Neskowin, where a concurrent suit was started by Lester Fultz, Bob Gormsen and Ray Wilson took the lead in gathering testimony. They spent days talking to people who responded, "Oh, sure. I picnicked at that beach 20 years ago, and here is a photograph to prove it." When the Circuit Court ruled that the beach law was valid, Hay was first to appeal to the Oregon Supreme Court. Associate Justice Alfred T. Goodwin heard the case. Having been raised in Oregon, he knew the state's long tradition of public use of the beaches. In upholding the Circuit Court ruling, he went back to the old English doctrine of custom. His opinion, handed down in December, 1969, meant that all Oregon beaches could be considered public recreational land based on customary use. It was a sweeping legal principle. With a wave of the hand, we were relieved of the burden of proving our case on a tract-by-tract basis. On the north coast, probably, we could have done it, but we had been concerned we would have trouble documenting public use in places along the less populous south coast.

At the time the Hay and Fultz cases began to test the Oregon Beach Law, State Treasurer Bob Straub said, "This is so important, we ought not to fool around. Let's buy the underlying fee. Let's get that behind us and not let the public's claim to right of access rest on judicial opinion." I said, "I agree with you, Bob." But Mr. Jackson and others said that was crazy. "Why should we spend money on land we already have a right to use and can regulate to a degree under the law?" Mr. Straub promoted a ballot measure to buy the beaches outright in 1968, but the voters defeated the proposal. It was too bad, because I think that would have been the right thing to do.

A little over 20 miles of tidelands, mostly on the northern Oregon coast, had been ceded to private ownership by 1913. At that point, Governor Os West said, "We've got to put a stop to this. Let's not sell any more tideland. It's too valuable." That's when he declared the beaches a public highway. In early days, in fact, the beaches were used as wagon and mail routes. He had the foresight to recognize their scenic and recreational value. I worry about the precedent of the ceded lands, though, and I think we should do something to more permanently protect the wet sands area, the offshore zone from ordinary high tide seaward out to three miles. What we have at present is limited control of that zone through a six year moratorium on offshore oil, gas and mineral exploration. This is a critical issue that is not generally understood.

Shortly after the beach law was enacted, the Highway Commission began a survey of the coastline in accordance with the instructions of the state legislature. It was recognized that the 16 feet of elevation line would be imprecise because the contour shifts with the moving sand. Three members of the House judiciary committee were appointed to establish the permanent beach zone line. Representatives George Cole, Gordon MacPherson and Tom Young, who later became a member of the State Parks Advisory Committee, came into the assistant Highway engineer's office and drew the public zone line on aerial photographs. "This ought to be about where it should be. Do you agree?" "Yes." "What about this headland?" That sort of thing. Lloyd Shaw devised the method of tying the zone line to survey points keyed to a coordinate system. As a result, a fixed zone line roughly approximating the line of vegetation was described from one end of the coast to the other and was incorporated into the beach law by the 1969 legislature. Having the line spelled out precisely settled things down. Here was the line beyond which you could do nothing without checking with those Parks people.

Interestingly, William Hay had carried his case to U. S. District Court in Portland and was prepared to go to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco, but Ted Goodwin was newly appointed to the federal bench there, and since Goodwin had just written the Oregon Supreme Court decision which went against his case, Hay dropped his suit. But the Oregon Beach Law is being tested again by another, more recent case involving property at Cannon Beach. Under provisions of the law, we denied an applicant's request for a permit to go seaward, beyond the zone line, for motel development. The property owner appealed our decision to Clatsop County Circuit Court and then brought suit against us in the Oregon Court of Appeals. Undoubtedly it will cost us a lot of money to defend against this newer suit as it moves through the courts.

As we fought the battle of public access to the beaches, it became clear that it was one thing to have right to enjoy the beach, and something else to get to the beach. After the beach law was passed and the zone line firmly established, we continued our efforts to provide access points. We had started with the fundamental question of how far people would walk. We said, "They might walk a mile or so, so let's say a mile and a half." As a rule of thumb, at three-mile intervals the planning and engineering staff tried to locate a place where a vehicle could get off the highway safely and there was room to install a parking area, picnic table and restroom building and let people get to the beach. Most of the smaller facilities you see on the coast fit that description. Much of the work is accomplished. However, we learned there are a lot of people who subscribe to the "not in my backyard" philosophy.

At Arch Cape, one of the delightful communities on the north coast, we had selected a site for beach access. A Clatsop County commissioner called me one day and said, "I think you'd better get up here. You've got a problem." I said, "Fine. Set up a meeting. I'll come talk to them." I was feeling pretty sure of myself in those days. I seemed to be able to walk into a crowded meeting room and say "Please settle down, folks. Settle down. We know what we're doing. You can trust us." And they would. Deputy Superintendent Lynn Koons and I drove to the coast. The meeting was held in the Catholic church. The place was absolutely jammed with people. The county commissioner introduced me. I stood up and said, "Ladies and gentlemen, I know you're upset about the idea of our developing an access point in your community. I'm here to tell you we are not going to proceed with it." Three hours later they were still chewing on me, they were so fired up. To this day, if you want to get to the beach in Arch Cape, you will have to park on the street and walk through somebody's yard.

There are other places on the coast where we were not able to get through, politically. The story of McVay Rock is one of my favorites. South of Brookings is a rocky outcrop just off the beach. It had been largely quarried for a jetty at Brookings harbor. It was owned by a lady who approached us and wanted to know if we wanted to buy it. Ray Wilson, our lands supervisor, negotiated a good deal, but it just sat there. We hadn't done anything with it. The seller came back and said, I have an idea. I would like to bring in an orchestra from, say, Willamette University so we can present some concerts out on the beach as the sun is setting. Wouldn't that be wonderful?" We said, "Yes." When the local newspaper came out with a headline announcing a proposed "McVay Rock Festival," the whole place was in an uproar. People assumed State Parks was going to put on a "far out" festival of rock music. To this day that park has not been developed, partly because the local comprehensive land-use plan is so restrictive. We just have to wait until the demand is there.

The beaches south of Brookings are private, for all intents and purposes, simply because you can't get to them. We have a little piece at Winchuck, near the California border, and we are trying to buy another nearby. Coming north, we have McVay Rock, and then you are into downtown Brookings and Harris Beach State Park. The fact that there are still places where the public can't get to the beach is not an easy problem to fix. You're not welcome in some communities because people from the outside will be following in your wake, and it isn't appreciated. It's a good thing we were able to do as much as we did before 1973. With the land use planning requirements that evolved under state law, I am not sure we could do as much today.

Scenic Waterways

Americans became conscious of the management of wilderness resources following the Wilderness Act of 1964, which designated millions of acres of specially-classified national forest lands for protection. Then, the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act was passed in 1968. As usually happens when an issue heats up, federal legislation is mirrored at the state level. That was the case with the scenic waterways program. There were those who had struggled in the Oregon Legislature trying to get a law passed to protect outstanding rivers. They finally decided they would take the option of initiative petition. Two of the sponsors were State Senator Don Willner and Representative Stafford Hansell. Stafford Hansell, a conservative hog farmer from Umatilla County out to save rivers, has a remarkable record of service in the public spirit. He and Willner and the others wanted to designate the Rogue, the Deschutes, the John Day, part of the Minam, the Owyhee and the Illinois for protection against dams, water diversions and uncontrolled riverbank development. Their initiative was referred to the voters in the fall of 1970, and it passed. The original waterways system protected 496 miles, and 573 miles have been added since the first six rivers were designated.

The State Scenic Waterways program essentially was an early land-use regulation program. We would classify the rivers. The classifications would indicate to property owners what kind of development was allowed. Bob Potter, one of the promoters of the initiative, was recommended to run the program and he came aboard. This is the way the process worked. If you are a rancher on the John Day and you want to put a mobile home near the river for your hired hand, you have to get a permit. The zoning rules stipulate that if you want to develop, it has to be for agricultural purposes. Based on the scenic waterways notification process, the mobile home should be screened, visually, from the river. Does the proposal significantly impair the natural scene as seen from the river? That's the standard by which we evaluated development projects. Right out of the chute, a fellow wanted to put a big recreation vehicle park on the John Day River. It was very controversial. Attorney General Lee Johnson jumped in his airplane, taking Bob Potter, and they flew across the Cascades to inspect the site. As a result, we condemned the property.

We got the plans in place and found out early that for the most part landowners adjacent to the rivers really wanted to cooperate. What they said was, "Look, we love these rivers. That is why we live here. It offends us to hear you suggest we would do anything insensitive." They were right. It is only a small number who try to take advantage of the situation, and those people are the ones we have to deal with. We can delay a development proposal for as long as a year, during which time we negotiate a compromise. In most cases, we can negotiate a satisfactory design solution. If we can't negotiate a compromise, we have the option of allowing the applicant to develop as he or she proposed, or we can acquire the land through condemnation if necessary. We seldom have used condemnation because most of the time we work out a compromise to protect the river. Our staff has done a terrific job.

A case that occurred on the Rogue River near Agness illustrates the principle of negotiating solutions to development conflicts. A landowner wanted to put in an RV park on a big meadow high above the river. The people across the river could see it, but people would not be able to see it from the water. Here again, Bob wanted to buy the whole thing, and I said, "We don't have to do that. Why don't we just have the landowner make a setback and plant a lot of vegetation?" Bob blew his fuse and resigned. To him, I was selling the farm. But if you go down and look at the place today, you see that the solution is acceptable. Bob Potter was an all-out protectionist, and I respected him for that.

An interesting element of this program is that the state-designated rivers also can be covered by a federal designation, which confuses things. On the Rogue River the question of regulation got to be very heated. The wild section needed to have public access regulations if it was to remain wild. The standard experience of those who entered the wild section was supposed to be a feeling of remoteness. Bob and the staff had done everything they could to figure out the optimum number of river users in a given period. They inventoried campsites and they did environmental studies. They found the Rogue floods annually and cleans itself out. It could take a certain amount of traffic. They finally came down this way. There are existing lodges in the wild section. They counted up the beds, and there were 60 in all. They said, "We can't deny access to that number. The lodgings are there. Okay, let's say 60 admissions for the private, or commercial side." Next, somebody said there ought to be 60 admissions for the public side, too, for people who don't want to go to lodges, but want to camp. That is how we got to the optimum number of 120 admissions to the wild section at a given time that is in force today. It seems arbitrary if you don't know the background, but it works pretty well.

The issue of regulation, of limiting the number of people admitted to the rivers, became highly controversial. I was not welcome in my hometown of Grants Pass because I was on the regulating side, where I had to be. The local people really hated it because on a Friday night they wanted to be able to put their boats in the Rogue on the spur of the moment as they always had before. Under the federal regulations you need a permit. You've got to apply for it in advance, and it's very bureaucratic. The same debate has raged on the Deschutes River for 10 years. It is not resolved yet. Most people don't like regulating the access at all. But it is my opinion, after having looked at the Middle Fork of the Salmon, the Snake, the Rogue, the Deschutes and others, if you really want to have an experience that is not crowded with people, you are going to have to regulate the number of users, unpleasant though it is, and expensive too.

We wanted to add the South Fork of the Santiam to the list of designated rivers, and the North Umpqua and the Grande Ronde. During Glenn Jackson's tenure as head of the Transportation Commission, it was the chairman's policy that if we wanted to add a river to the scenic waterways system under the law, fine, but we had to have the county commissioners with us. That stopped all of those projects because, politically, they just wouldn't work.

Another issue arose. The environmental community didn't always feel comfortable with how the Forest Service was managing federal forest lands. They got the legislature to designate Waldo Lake and the North Fork of the Middle Fork of the Willamette as State Scenic Waterways, thinking that they could get us to influence the Forest Service. Those were confusing times.

The river enthusiasts of Oregon have become a large activist group with a number of causes and political cross currents. They decided to go to the public with an initiative petition to add 10 more rivers to the system. The voters approved Ballot Measure 7 in the election of 1988. The measure was passed because people in Portland, Salem and Eugene liked it, but most of the rest of the state didn't. It doubled the miles of river we have to manage. We have to put all the management plans together. One of the results of the economic slump of the 1980s was that we had to scale down the scenic waterways staff. It's a real problem for us.

My observation, after having dealt with the issue over many years, is that zoning is not the problem on the rivers. Most people are willing to accept it, and Oregon's zoning laws really are pretty good. What we've got is a people-management, or access-regulation issue. That is really the basis of the rivers controversy. The rivers provide wonderful recreation activity, which people love. But they cut through jurisdiction after jurisdiction, and management becomes very complex. As the public tries to deal with it and understand it, they get all kinds of signals. The Bureau of Land Management says this, and the Indian tribes say that; State Parks says this, and the State Police, Fish and Wildlife Department and the Division of State Lands have something to say, too. A lot of tine and energy is spent in coordination. We have spent 10 years on the Deschutes and we still have not resolved all the conflicts. On top of that, then, is the federal system. When United States Senator Mark Hatfield got through an omnibus rivers bill in 1988, a number of Oregon rivers were added to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers system. Oregon has become the "river" capital of America, I think. When you ask anybody where they are "doing" rivers well, they will say Oregon. Our state legislation has more "teeth" in it than other state scenic waterway laws. Most of the others are planning admonition laws, as I see them. "Go forth and plan." We, on the other hand, can protect rivers in Oregon. We have a way to do it, most of the people like it, and it does work.

Recreation Trails

The Recreation Trails program is something of a mystery to me. When the National Trails System Act was passed in 1969, the trail lovers of Oregon, of which there are many, thought, "We ought to have a law like that at the state level." Once again, Senator Willner and others tried to get legislation through. The special interest groups, the timber and agricultural people who opposed trails and others concerned about property rights, were successful in beating them back until the proponents finally got a compromise bill through in 1971 that was supposed to mirror the federal law.

I told my trail friends at the time, "If you wanted me to build trails, you just took away my ability to do it." There was no provision for condemnation. As a consequence, the State Recreation Trails program began as a promotional effort, but people felt good about it. We hired a trails coordinator, Jack Remington, to put a plan together. Planning is important, but the measure of success for me is, "How many miles of trail did we get on the ground this year for people to enjoy?" I find I am one of the few people who really cares about that. Trail users like the idea of inter-connected trail systems. One of the first such systems to be promoted was the Coast Hiking Trail. Samuel Dicken, a University of Oregon professor of geography who loved the coast, said, "We ought to be able to walk from Washington to California." Everybody said, "Yes!" I said, "Hold it. Nobody's going to do it." But they liked the concept. The regional trail system idea is very popular. To this day we spend time and money trying to build one of those trails. What happens, of course, is if you build it, most people walk just a section of it at a time. It works perfectly well that way.

The Recreation Trails Council, established under the law, is a citizen body whose mission in life is to keep banging the drum for trails. They operate from a plan. It needs to be updated. There is a section of the Land Conservation and Development Commission's statewide land-use planning program, under Goal 5, that talks about trails. We got our noses bloodied on a proposed trail from Corvallis to the coast which crossed the forested Coast Range. The timber companies went crazy when they saw that line on the map. Jack and the people who put it together said, "We'll just use these logging roads, and if you don't want us to use the logging roads for some reason, if you have a fire problem for instance, we'll temporarily close the trail to hikers." They could not accept it. According to LCDC Goal 5, however, local government is supposed to encourage and protect recreational trails. The High Desert Trail around the Steens Mountain area has worked pretty well, largely through the efforts of Russ Pengelly. Nevertheless, we have not been successful in fully implementing the state-coordinated plan because of conflict with the property rights issue.

When you say "trails" in Oregon, you really are talking about the United States Forest Service. The National Forests are where most of the trails are. The problem is they are at a high elevation, accessible only for a short season. What we ought to do to be consistent with the legislation is try to get the trails down at lower elevations near population centers, like the Columbia Gorge. We are working on a cooperative project to develop a low-elevation trail in the metropolitan area that would be accessible for a longer period of the year. It is known as the 40-mile Loop. And there is talk now about a trail from Portland to the ocean. Here again, it would be one of those regional systems. I don't know who would do it, but people get really excited about the possibilities.

Trails are a popular activity with splinter constituencies. I go to then pretty honestly and say, "If you want to move trails ahead you have to find some special funding source that is tied to the user." They say, "Okay, what kind?" And I say, "Well, that's your job. Be creative." Nothing has ever happened. Building trails is expensive, and we don't know how many people use them. Everyone likes them, but we have a hard time documenting the demand. We have counters on some trails now. On summer weekends you will see plenty of people out. The Silver Falls State Park trail system is heavily used, there is no question about that. I don't know how many people go down the Pacific Crest Trail along the ridge of the Cascades each year. In certain areas I think it is heavily used, but how many people hike all the way from the Mexican border to Canada?

The plan for the coast is to build the trails over the headlands and use the beach where possible. Right now we are stuck at Road's End, north of Lincoln City. Once we get through Road's End we will be back on the beach, heading south, and we'll get clear down to Yachats, probably, before we have to climb back up. The current trails coordinator, Pete Bond, already is dealing for trail easements in Yachats.

Securing the Yachats 804 Trail, a section of allegedly abandoned Lincoln County road right-of-way, is an interesting episode. I've long regretted the fact we didn't pick up that cause earlier. It should have been a Parks cause to protect that old right-of-way, but we ducked it at first. The proponents, known as Save the Yachats 804 Trail Committee, headed by Bill Adams, for something like 15 years fought for the public's right of access through the courts and won. The case was based on the principle of prescriptive rights and the rationale was that because the right-of-way had not been abandoned, the land did not revert to adjacent property owners. After the case was upheld by a ruling of the Oregon Supreme Court in 1985, State Parks agreed to take over the right-of-way and develop it for a hiking trail. We have that valuable addition to the coastal trail system thanks to determined citizen activists who knew what was right.

Columbia River Gorge

The Columbia Gorge is the object of a variety of recreation and protection programs. If you look at Oregon State Parks, historically, you will see a significant investment of agency effort on the gorge over many years. It was a priority for Superintendent Boardman. I've spent a lot of time in the gorge, and I have ambivalent feelings about it. It is not a Crater Lake, it is not the Grand Canyon. It is where a major river cuts through a mountain range. If you appreciate geologic spectacle, it is a pretty exciting place. It also is a main travel corridor, so the scenery is highly visible. The interstate freeway follows the Oregon side of the Columbia. I spent a full day up there not long ago, at Mayer State Park, where the wildflowers were so beautiful, the display knocked my eyes out. The system of parks in the Columbia Gorge that Sam Boardman put together was essentially butchered by the freeway. The dams took their toll too. The watergrade parks are bits and pieces left over from highway construction of the 1950s for the most part. Some of the highway people anguished over it, but with the railroad and the river on one side and the Cascades on the other, there wasn't a lot of room to move. They had to build out into the river in some places, which would be difficult to do today with the present environmental consciousness.

The only good park development to come out of the freeway construction was Rooster Rock. Koberg Beach is gone, and one after another the areas were eroded. Enough is left to work with at Mayer, where there is a great recreational opportunity on the water. Windsurfing is a big business, and the windsurfers have leaned on us really hard to get access to the river. We would like to comply, but we would rather provide access to the river for all kinds of public use, not just windsurfing. A lot of people want to get to the water. We are going to end up with a half a million dollars, at least, in the little facility at east Mayer State Park. We would have to project millions to complete another access at Sculley Point because we would have to go under the freeway and under the railroad. I don't know if it will happen. Windsurfing on the Columbia is a huge attraction, and it has helped the adjacent communities, Hood River in particular. The local economy has leaped forward. To drive down the freeway and suddenly come upon all those sails with their brilliant colors out on the river is an exciting sight.

I had a bit part in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area legislation. Charles Odegaard, who was director of Washington State Parks for years and is now National Park Service regional director in Seattle, would talk with me about how Puget Sound controls politics in the state of Washington and how that didn't bode well for state park expenditures in the gorge. Trying to get political support to save the Washington side of the Columbia was a losing battle. In Oregon, on the other hand, Portland is the major political base, and it is right next door. People are knocking one another over trying to save the gorge. The impasse was on the other side. The breakthrough came when Governor Vic Atiyeh convinced Washington Governor Booth Gardner that they ought to get together and push for a national scenic preserve. I became a courier carrying proposals between Pat Amedeo and her Natural Resources counterpart on the governor's staff in Olympia. Those were interesting times. When we finally got agreement between the two governors, things really started to happen. That's when Senator Hatfield and Washington's Congressional delegation said, "Let's go."

As a consequence of the Columbia Gorge National Scenic Area Act of 1986, we have a multi-layered, bi-state Columbia River Gorge Commission and U. S. Forest Service operation. The bi-state Gorge Commission is to see that local units of government on both sides of the river adopt land use plans and zoning ordinances consistent with the federal act and commission plan. I tried to convince the commission that its professional staff should be the Forest Service, with whom it is supposed to be working in partnership. Instead, adversarial relationships developed, as is natural in turf conflicts. The federal money will not be appropriated until all the counties involved get their land-use plans together. That's how the Feds hold local government's feet to the fire. No money until your plans are approved. It is expected to be pretty easy to comply in Oregon because of our mandatory statewide land-use planning program. It is going to be tough to get local government on the Washington side to sit down and talk about land use and zoning. They just don't want to do it. But the gorge will be better off when all the plans are in place.

In the Columbia Gorge, as with the Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area on the coast a decade earlier, Oregonians were shy of "locking up the whole place in a National Park." But tourism benefits can be much greater in the sphere of National Parks. The public is more familiar with National Parks than National Scenic Areas, so the park designation can have a pay-off. For years, the National Park Service maintained a field office in Portland largely because of Gertrude Jensen and her work with the early Columbia Gorge Commission. She promoted National Park designation in the 1940s and '50s so actively that a small staff was fully occupied with matters relating to the gorge. One particularly prominent man-made feature within the gorge has received a lot of attention. The old Columbia River Highway is a gem that is carefully watched over and promoted by the Historic Columbia River Highway Citizen Advisory Committee. On the question of a continued commitment from Oregon State Parks, I have indicated to the Feds that we will continue our modest acquisition program in the gorge, and State Parks will continue to be a major supplier of recreational facilities. We are not concerned about who is the boss. If we think something needs to be done, we will work it out somehow. I have learned, after coming through the statewide land use planning process, it is a waste of time to get into an argument about who is the boss.

Right now, most of the acquisition activity is taking place on the Washington side, where fewer public lands are in place. There are some great rivers over there. During their journey down the Columbia in 1805, the explorers Lewis and Clark spent more of their time on the Washington shore. There is less mountain shadow over there and better river access. Potentially, there is more recreation land on the Washington shore than there is on the Oregon shore. Yes, they have a railroad paralleling the shore, but you don't have that big freeway to interrupt things like we do. I think the gorge is going to be well cared for. The big argument will be about development. How much is enough? How far are we willing to go to accommodate increased recreational demand? Good planners and good managers will figure that out.

I met with the Oregon Gorge Commission recently. It is headed by Stafford Hansell. I walked in and said, "I am not here with any problems. I am just here to say hello and let you know that we are watching and want to help. Hang in there. It's not always fun." They almost hugged me. I don't think many had done that before. There are nothing but problems coming at them. They are nice people and very committed. They are dealing with tough issues, including Native American fishing rights, archaeological site protection and traffic control on the water. Barging on the Columbia is a given. I don't think you can change that. And, of course, it conflicts with the pursuit of windsurfing. The barge people say, "Hey. You'd better look out because I can't see you, and I can't turn." Thinking of the wind as a commodity, I am reminded of the gigantic windmills on the south coast that cropped up during the energy crisis years ago. One long-time Cape Blanco rancher is reported to have said, "You know, I have been fighting this wind all my life. I almost have to tie my sheep down when they graze, because it blows so hard. Now the wind-power people have come in here and I can sell it!" We have something of the sort going on in the Columbia Gorge. Before windsurfing, the strong wind was something you put up with. Now it is the basis of an economic boom, while the windmills in Curry County have gone the way of buggy whips.

|

| Fig. 24. Leading figures in the politics of parks and outdoor recreation in Oregon in the 1960s and '70s are pictured in the ceremonial office of Govenor Mark O. Hatfield (right) on January 4, 1965. Newly-elected officials, Secretary of State Tom McCall and State Treasurer Robert Straub (standing), execute their oaths of office while Alfred T. Goodwin, associate justice of the State Supreme Court, looks on. The then-current and two future governors each had important roles in developing public policy on beach access and scenic river protection. Justice Goodwin wrote the 1969 State Supreme Court opinion upholding the open beach law when the legislation was tested in the courts. 1965. Photographer unidentified, Oregon Historical Society, #cn 012489. |

|

| Fig. 25. Governor Tom McCall (center) studies a prospective public beach zone line with State Representative Norm Howard (left), vice chairman of the House committee on highways, and Dr. Herb Frolander, a technical adviser from Oregon State University. Not fully pictured is Representative Sid Bazett, chairman of the House committee on highways and a key sponsor of the legislation governing beach access above the wet sands. After this field check on May 13, 1967, Governor McCall and his advisers recommended a zone of public access extending to 16 feet above sea level that was adopted by the legislature initially. Governor McCall signed the beach bill into law on July 6, 1967. Two years later, a permanent, fixed-point zone line was established by survey and legislative action. 1967. Photographer unidentified, Oregon Historical Society, #cn 021334 |

|

|

Fig. 26. Participants in the 1967 State Parks

and Recreation Advisory Committee tour stopped at Neskowin Beach

Wayside on the north central Oregon coast on August 10 to meet Lester

Fultz, who was to be litigant in one of the initial court cases that

tested the Oregon Beach Law. At issue was construction of a private

road on Neskowin's South Beach that was under construction when the

beach bill was passed by the Oregon Legislature in June. After the bill

was signed into law a month later, development seaward of the line of 16

feet of elevation required a permit from the State Highway engineer. Pictured, clockwise from left: L. L. Stewart, Dave Talbot, Irving Anderson, Ed Schroeder, Pete Foiles, Lloyd Shaw, Lester Fultz, Bob Wilder, Bill Kanoff, George Ruby. 1967. Oregon State Highway Department Photo. |

|

| Fig. 27. A campaign to promote safety on Oregon beaches was launched in 1984 with Cap'n Beware, the beach safety bear, as the identifying symbol. In the same year, the Parks organization cooperated in the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Department's successful initiative to rid the beaches of plastic litter threatening to sea life. During the first large-scale beach clean-up effort, on October 13, 1984, as many as 2,000 volunteers collected 26 tons of plastic debris for disposal and recycling. In the recurring campaign, state parks and waysides were put to use for staging areas where park managers supported zone captains assigned to locations up and down the coast. During the Parks-sponsored "Company's Coming" clean-up in 1986, beach safety and the environment became joint promotions when ocean shores coordinator Pete Bond appeared in the Cap'n Beware costume. Here the beach safety bear gives encouragement to Deb Schallert, a ranger at South Beach State Park, Newport. 1986. Oregon Department of Transportation Photo. |

|

| Fig. 28. In 1975, bicyclists led by Transportation Commission Chairman Glenn Jackson wound their way from the Lewis and Clark College Law School in southwest Portland to dedication ceremonies at Tryon Creek State Park, located near the outlet of Tryon Creek to the Willamette River. To the right is Oregon Governor Robert Straub, whose personal vision of the Willamette River Greenway concept in 1966 included a continuous system of river-bank bicycle paths between Portland and Eugene. 1975. Dana Olsen Photo. Courtesy of David G. Talbot, Salem, Oregon. |

|

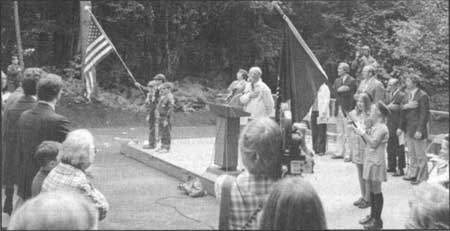

| Fig. 29. Tryon Creek State Park, a wooded, creek-canyon tract lying between Portland and Lake Oswego, was acquired and developed as the result of a community action campaign begun in 1970. Its primary attractions, the nature trail and interpretive center, were projects of the Friends of Tryon Creek State Park, one of the early citizen volunteer groups organized to support educational activities in state parks. On the platform, taking part in the presentation of colors during dedication ceremonies, July 1, 1975, left to right: Cub Scout Pack Troop 110, Riverdale School; Lucille Beck, co-founder with Jean Siddall of the citizen movement and fund drive; William Oberteuffer, board member of Friends of Tryon Creek State Park; Barbara Fox, Friends board chairman; the Reverend Taylor Potter, Lewis and Clark College chaplain; Governor Straub Glenn Jackson, Parks Superintendent David Talbot, Girl Scout Pack Troop 383, Forest Hills School. 1975. Photograph courtesy of Friends of Tryon Creek State Park |

|

| Fig. 30. In 1971, following voter approval of the ballot measure creating a state system of scenic waterways, the Parks and Recreation Advisory Committee traveled a section of the Deschutes River as part of the annual inspection tour. The party is shown putting into the river on the east bank, below the Warm Springs Indian Reservation. In due course, public access points were improved by cooperating agencies using dedicated funds from the sale of boater passes to the scenic waterway. 1971. Oregon Department of Transportation Photo. |

|

| Fig. 31. In the early 1980s, Governor Vic Atiyeh defined and directed the state's role in securing one of Oregon's outstanding fishing and whitewater rafting streams for public recreation. The State Parks and Recreation Division and Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife coordinated efforts with fund-raising by the non-profit Oregon Wildlife Heritage Foundation to acquire 15 miles of privately-held frontage lands on the lower Deschutes River. The major purchase for public ownership was completed in 1983. The governor is pictured during ceremonies on June 23, 1988, at which time the Deschutes River Recreation Area was dedicated in his honor. 1988. Photograph courtesy of Victor G. Atiyeh, Portland, Oregon. |

|

| Fig. 32. In 1986, following years of interagency coordination and negotiation between the neighboring states, a 290,000-acre Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area was created in Oregon and Washington by Act of Congress. The Columbia River Gorge Commission selected Crate's Point near The Dalles as the site for a visitor information center. On March 16, 1990, Senator Mark Hatfield, a key sponsor of the National Scenic Area legislation, unveiled a signboard marking the site of future development. The visitor center is a cooperative project of Wasco County and the U. S. Forest Service under auspices of the Columbia River Gorge Commission. 1990. USDA Forest Service Photo. Courtesy of Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

development2.htm

Last Updated: 06-Aug-2008