|

OREGON'S HIGHWAY PARK SYSTEM: 1921-1989 An Administrative History |

|

DEVELOPMENT OF THE STATE PARKS AND RECREATION PROGRAM 1962-1989: A PERSONAL VIEW (continued)

III. Professionalism in Parks management

What are your observations about the growth of professionalism in parks and recreation administration over the years you have been engaged in the field? Specifically, how do you think statewide and national organizations have assisted the development of Oregon State Parks?

During the time I have been associated with State Parks, there has been relatively little preoccupation with traditional professional background and connections. These things evolved naturally from the time of Harold Schick. In the 1960s, much of the field organization carried over from the preceding decades, and the central staff essentially was made up of technical people with some background in engineering or landscape architecture; landscape architecture, probably, more than anything else. The national professional organizations in those days consisted of the National Recreation Association, the National Conference on State Parks and the American Institute of Park Executives, which later merged with NRA to become NRPA, the National Recreation and Park Association. I was involved in all of them.

For the first few years after I became State Parks superintendent, I didn't have much time to spend in professional organizations. Previously, I had been a founding member of Oregon Park and Recreation Society and I was one of its early presidents. The OPRS was an association of local park and recreation professionals. There may have been 20 of us throughout Oregon. We were affiliated with the League of Oregon Cities.

The National Conference on State Parks was exciting to me. My first experience at a national meeting was in a huge forestry center north of Toronto. I got started there and enjoyed it a lot. The National Conference sponsored the meetings I could attend once a year to associate with people who dealt with the same problems I did on a day-today basis. No other group I knew of offered as much. I really looked forward to getting down to the "nitty gritty" of parks management, even to such ordinary matters as dogs in the campground. If you wanted to get a spirited conversation started in that group, you could talk about dogs in parks. It was serious business. These were the people who had solved the problems. It was exhilarating to talk to people like Conrad Wirth, who directed the National Park Service from 1951 to 1964 and initiated the far-reaching, strategic Mission '66 program. I sought out the delegates I liked and those who gave sound advice. Connie Lickel of Pennsylvania was one of them. He managed a state parks system that looked a little like ours. Before I went to those meetings, I would decide what three to five issues I wanted to concentrate on. That helped me keep things in focus and bring home useful information.

As junior members in the 1960s, Washington State Parks Superintendent Chuck Odegaard and I and a number of others noticed that the National Conference was, in some ways, a social club consisting of retired National Park Service officials and their old friends in state parks. Because National Park alumni tended to control the proceedings, Connie Wirth, somewhat unceremoniously, would be elected president every year. Often, we didn't have the time to discuss the issues because we were a bus load of people being whisked around to look at trees.

One year, a situation occurred at the annual meeting in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. I was on the board of directors at the time, as were Chuck and Bill Beckert, who was by then director of Idaho State Parks. "Is there a nomination process or some such thing," we asked? Connie reared back in thought. He said, "I would like to appoint Odegaard, Talbot and Beckert to the nominating committee." He shouldn't have done that, I'm afraid. We closeted ourselves and decided it was time for new leadership in the National Conference on State Parks. Poor Bill Beckert just about had a heart attack. He did not want to be part of the palace coup at all, but Chuck and I said, "It's now or never." Economist Marion Clawson was a board member of Resources for the Future, a wonderful man. We thought, "How could anyone be against Marion Clawson?" We placed his name in nomination and that was the end of Connie Wirth's sway. That election marked the beginning of a significant shift. The next thing we did was move a step farther by rewriting the constitution to make the organization the National Association of State Park Directors. The National Association, then, clearly became a forum for the 50 state park directors to help one another, particularly the new people coming along, many of whom were political appointees who might or might not know very much about parks, almost all of whom were dead serious and wanted to do a good job.

The National Association of State Park Directors was very useful, and I was an eager young person in those days. I had become frustrated by some aspects of the Land and Water Conservation Fund program. There was renewed emphasis on planning, and the Feds based their apportionment of the money on performance of planning tasks. The Land and Water Conservation Fund program grew in influence following enactment of the enabling legislation in 1964. The National Association of State Park Directors was reinforced by a separate organization, the National Association of State Outdoor Recreation Liaison Officers (NASORLO). The two groups involved many of the same players. Initially, the liaison officers who administered the federal-aid program at the state level were appointed by the governors. They included, say, the director of Natural Resources for the State of Michigan and other top administrators. When you got them together in a room, you could feel things start to happen. As state liaison officers, we were capable of lobbying significant sums of money from the Land and Water Conservation Fund. Over the years, as other matters claimed our attention, we delegated representation at the meetings, and the organization lost some of its political clout as a result. On the other hand, the emphasis on professional planning strengthened correspondingly, and that has been generally beneficial. In our part of the country, for example, the Pacific Northwest Regional Recreation Committee has made major strides in long-range forecasting of outdoor recreation needs in Oregon, Washington and Idaho. At present, Don Eixenberger, our recreation research analyst, represents Oregon State Parks in that regional planning effort.

The Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management, between them, control close to 50 percent of Oregon's land base. Yet, when it comes to recreation planning, I have always felt the federal agencies were ready and willing to follow our lead. They are content, I think, if we provide strong leadership in that area. We are moving in that direction right now. In 1989, we had the governor's executive order creating the Oregon Outdoor Recreation Council, which was to represent the public suppliers of recreation at federal, state and local levels. The Council's purpose is to discuss priority issues and develop strategies for improvement. It has been of great assistance to us in the statewide comprehensive outdoor recreation planning process. The National Park Service has not had an administrative presence in Oregon since the Portland field office was closed. There is a more distant relationship as a result, and I think the Park Service looks upon us as being a little like an outlying territory. I think the counties regard us in the same way that we look upon the federal government.

There is a certain uncomfortable feeling about how the larger jurisdiction deals with and helps its smaller units. The County Parks Association was created 30 years ago. It was organized for county government in much the same spirit of benevolent self interest with which the National Park Service encouraged the National Conference on State Parks. The objective, as far as I was concerned, and Clayton Anderson too, who was my predecessor as state recreation director, was to get the counties involved in the supply end of recreation and relieve State Parks of some of the pressure. It worked. However, we reached a point where our supervision of county programs aided by the Land and Water Conservation Fund money was too strong, and it was resented. The counties said, "Get out of here, please. We'll operate on our own." Now, we have to devise a strategy for restoring state and county cooperation, and it should be done soon.

Oregon's Outdoor Recreation Delivery System, the report prepared by James M. Montgomery Consulting Engineers of Portland in 1980, was intended to bring state and local parks agencies together to sort out relationships and responsibilities. We were to find a common funding source so we wouldn't be fighting over who gets the money. The consultants objectively related the shortcomings of the parks and recreation profession in Oregon. It was overwhelming to many, but I agreed with it fully. It stands today. I regret to say that we do not have standards to which we all subscribe with regard to what is good, what is bad and how much is enough. We are reluctant to come to the negotiating table for some reason. If we go to the public and the legislature as a profession and say, "We need money for x, y or z," we have to be able to present an explanation of why that money is needed. Why is it we need more acres of park land in Milwaukie, Oregon? Why is it we aren't keeping pace with the demand for soccer fields? Do we need more water access, or should we concentrate our efforts elsewhere? The way it works now, each jurisdiction pursues its own goal, whatever can be achieved.

Rather than help us find a new funding source, the counties went to the legislature and succeeded in getting into the recreation vehicle registration money on which State Parks depends. Although I realize State Parks is not the only agency providing services to RV users in Oregon, it was nonetheless unsettling. They devised a strategy that I couldn't defend against philosophically. Through a registration fee increase, they wanted to add to our RV revenue so that their needs as well as ours would be met. The question put to us was, "If we get a little more added on top of that money for us, how would you feel about it?" I had to say, "As long as our needs are taken care of, I guess I cannot object." And it happened. We got $10 added and they got $6. That's the way it is. But the question of who is supposed to do what, and how the revenue should be shared remains with us still. Perhaps I am naive to think we ought to be able to trust one another and act professionally. In terms of parks and recreation, few people ever have been able to explain to me what they think is meant by "acting professionally." I have thought about it a lot, and I would think to act professionally is to make decisions based on the greater good, what you know to be in the best interest of the thing you stand for. In our case, parks and recreation. You make a decision without respect to what is good for you personally or organizationally. That may be an idealistic view, but to me that is what professionalism means. You disassociate yourself from your personal feelings and you do the thing that's right because you know it's right.

Looking at a map of the state, I remember saying a long time ago, "People, look. If you really want to serve Oregonians from the standpoint of outdoor recreation, the smartest investment for your dollar is to put it on federal land." I was an advocate in the 1960s and '70s of state aid to the federal government. If we could lever the Feds to build campgrounds and boat ramps and maintain them, would that not be a better investment for the state of Oregon than to ask the Feds to give us money to try to do something? Nobody bought my argument at all. With something like 52 percent of Oregon being in federal ownership, if we could get the Feds to manage their lands to serve the citizens of Portland, Medford and Ontario, say, and our out-of-state visitors as well, we would be miles ahead.

One of my dreams for the Outdoor Recreation Council that we sponsor is that when we understand what the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management needs are we can work through our governor and our Congressional delegation to get the Feds the money they need to do the job. In the recreation corridors of the Santiam and McKenzie River canyons you've got the green Forest Service pick-up going one direction, the orange BLM truck heading the other, both of them passing State Parks and county park service-vehicles. I am hopeful something better than duplication of effort will occur if we get the agencies together, resolve the issues and come to a working agreement. That is what I hope will come from the work of the council.

I'm confident the Outdoor Recreation Council will continue to play an advisory role in the responsibility of maintaining SCORP, the Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan, which is updated on a five-year cycle and is regarded highly by a lot of people. There were problems, politically, with our funding allocations in early editions of the SCORP, but we seem to have gotten away from those and are now able to describe the kinds of things that need to be done so that everyone can participate. I am impressed and pleased to see the number of people who use that document. On the other hand, I am concerned by the way we fail to use some of the information we develop. We do a state park visitor survey every five years. Only a few people seem to care about it and apply it to decision-making about park development, which is frustrating.

I have been asked, "What kind of professional training should the people in State Parks have?" I think we have come a long way on that. Probably about half the people that come into the field organization now come in with a four-year degree of one kind or another. The other half bring an equivalency in experience. That seems to be working. I am reluctant to turn ours into the type of parks organization where some employees become the officer class and deal with the public, while the maintenance people are regarded as enlisted personnel. I don't find that very appealing from a professional point of view. We always have had solid engineering capability. We have excellent professional people, landscape architects and planners. That has probably been the major break through. We are now attracting generalists who can do a lot of different things, who can dive into forest planning, wilderness and ocean shores resource studies and all kinds of things, rather like utility fielders.

I have tried to keep track of the professional programs at the University of Oregon and Oregon State University. In the 1970s, when Stub Stewart was on the State Board of Higher Education, he came to me and said, "There is a park and recreation program at the University of Oregon, there is one at Oregon State, and they both are built into physical education curricula. At OSU there is some talk of shifting the recreation program to the School of Forestry and letting the University of Oregon teach parks administration in local government, the operation of city playgrounds and that kind of thing. Oregon State University can specialize in forestry and non-urban parks and recreation. Does that make sense? Should we go ahead, and will you help?" I said, "It makes sense, and I will help." We were able to extricate the recreation program at OSU from the Department of Health and Physical Education. It has grown tremendously as a result. The recreation program at the University of Oregon has followed the market. At one time its thrust was municipal, or public administration, which is what it was when I was a student there in the 1950s. Now, it specializes in therapeutic recreation, private and military recreation, because the demand is there. One of the things I would like to take up with the Outdoor Recreation Council is the review of educational programs. Are the universities turning out the kinds of people that we need in the 1990s? I think the council is an appropriate forum in which to consider that question in the spirit of support, both of our profession and higher education.

We have not been able to attract many graduates of the program at Oregon State University in recent years because the federal agencies pay more, have more position openings and offer more upward mobility than an organization of our size can. The OSU program draws a number of people who want to get into interpretive work, which is an educational aspect of recreation where you tell the public about the natural, historic and cultural values of parks. A lot of students gravitate to that area. Then they graduate and find there aren't many jobs of that kind. They have trouble making their way in the field and end in having to do something else. This is one of the problems that needs to be looked at. Institutions across America have had to change in order to adjust to economic troubles of the 1980s. The facilities that are properly managed and well positioned are going to do just fine. The ones that aren't are going to have problems. I like to think of this as a period of healthy adjustment, a jerk in the continuing process that has caused people to step back and look at things in the light of what is really important.

Another concern for us is affirmative action. I have been married to an outstanding woman and have an outstanding daughter who caused me to pay close attention to this issue. I have concluded after all these years that if we aren't fully responsive to the need for equitable work opportunities for women and minorities, the situation never will be corrected. The imbalance will not correct itself. We are struggling with it mightily, and have begun to make some pretty good strides. As an example, you have a district manager position open and you think to yourself, "This may be an opportunity for an affirmative action appointment." But if you are seriously concerned about the advancement of females and minorities, it could be inadvisable to put your candidate in that situation and doom them to failure unless he or she is adequately prepared. Accelerated advancement singles out the employee and puts on a lot of pressure. I have talked to men and women in the field organization who don't want the manager's job if it's just because they are a member of a minority group or are a female. We seem to be able to get them up to the junior management level, the ranger levels and into lower management, and then they seem to leave us. Possibly they leave because there are greater opportunities elsewhere. The job market in our field for capable females and minority members is highly competitive.

I am afraid our organization is guilty of some fundamental "good 'ol boy" mentality. It is natural. Put yourself in the position of the park manager at any park. You have got to run the booth, you've got to run the tractor and you've got to do a lot of other things. You are going to want to place your people in the jobs for which they have the appropriate skills because that just makes sense. You are going to get things done faster and your life is going to be easier. Well, the woman ends up in the booth and the guy ends up on the tractor. But the woman wants to get on the tractor, because she has never been on a tractor, and the guy doesn't want to get in the booth at all. Being sensitive to everyone's needs can be difficult, but there is a way to do it. We can retain more of the females and minority members by preparing them for advancement into the management ranks, which is where our shortfall is. I have been tremendously encouraged by the staff that has come to this organization and invigorated it over the years. I'm excited about the current infusion of new blood and talent into State Parks from a number of professional disciplines and backgrounds. Without question, we are going to need good people doing their level best if we expect to sustain the system in the years ahead.

One of the most frustrating things I have had to contend with in the past is the tension that sometimes cropped up between the field organization and the central office in Salem. I call it the "we and they" phenomenon in which Salem gets blamed for all the difficulties. My current deputy, Larry Jacobson, has done a fine job of decentralizing financial management, personnel supervision and other aspects of our operation. This stops the "we/they" thing because most of the decisions that affect the lives of the field organization are made now at the regional level. A momentous personnel decision a few years ago helped spark the positive change. We chose Ron Hjort for the top management position in the south coast administrative unit from local parks and administration, placed him there directly from outside the system. It was a good move for us professionally, but it rocked the field organization and caused some real strain for a time. One of the first things Ron did was hold a meeting of staff throughout his entire region. No region supervisor had ever done that. Never had everybody heard the same thing at the same time. People could not peddle information as power, using it or withholding it. He just opened up the whole thing. After Ron's example, the other regions followed suit. The "we/they" thing is falling fast, and nothing could make me happier.

We have been extremely fortunate over the years that there have been people like Larry Espey, state coordinator of the Oregon Parks Foundation, who, although working outside the agency, are closely associated with us through tremendous work effort in support of our mission. The Parks Foundation, an outgrowth of a private foundation in the metropolitan area, was organized in 1972 to foster recreational development statewide. As a private entity, it accepts donations of property and funds to secure open space and lands suitable for more intensive recreational use. In this way, the foundation has made valuable additions to the state and local parks systems.

Probably no one in the "associate" category has supported State Parks longer or more vigorously than L. L. "Stub" Stewart, former legislator and long-time chairman of the Parks and Recreation Advisory Committee. Stub is a highly organized, tightly managed man. If you say that you are going to do something, he expects you to do it. And you had better deliver. I learned an enormous amount from him about professional courtesy. For example, after every meeting he would call or drop a note and say, "Good meeting. These people did good things." Always positive reinforcement. In his role, he was the ultimate chairman. It was his style in running a meeting to draw everyone into full participation. An issue would come up, there would be a staff report, he would ask for questions. "Do you need more information, anybody?" To make certain, he would go around the room, person by person, saying "What do you think?" He would draw people out, and it was astonishing, sometimes, what they would say when forced to explain how they felt. It was wonderful. In this way, the shy and the reticent who had a lot to offer were encouraged to contribute and were better prepared to do so the next time.

Before his retirement, Stub presided over Bohemia, Inc., a prominent family-controlled regional lumber company. He literally was raised in the tradition of industry. One of the admirable things about his career as a citizen adviser was that even though he might not always agree philosophically with some of the protectionist responsibilities we had, he knew detachment was part of his job. He never tried to work behind the scenes or to lobby me for a position he knew I couldn't take. I always appreciated that. And he always was available. During the more than 20 years he headed the Parks Advisory Committee, he would call me at least once a week, and we would talk. I could go to his office to discuss problems I wouldn't take to anybody else because I knew he would tell me the truth, whatever it was. I am a great fan of "Stub" Stewart. He has done a lot for Oregon and continues to serve the organization as a member of the new Parks and Recreation Commission.

While on the subject of the growth of professionalism in parks administration, I want to come back to Oregon Park and Recreation Society (OPRS), which currently houses a professional staff of one in our central office. I had been feeling a little guilty in recent years about our living up to the state recreation director's statutes. That is to say, I had wanted to reach out more to local government and help them do their part, whether it's the neighborhood playgrounds or the forest park. So much of the recreational service provided in Oregon is supplied at the local level. It occurred to me to ask, "Why don't we contract with OPRS to fulfill part of our coordination responsibilities? We will put their staff here, provide them with a telephone, and as the public comes to us for assistance with local issues, we can get OPRS to take charge." I am really glad to have them here. We share common goals, and I think the closer association is good for state-local relations. I am at liberty to ask OPRS to give us a hand on things that will help them to pay the rent. In return, we have cosponsored the society's annual meeting and have encouraged members of our organization to belong to the society and help support it financially. This is an excellent way to promote professional growth among the junior staff and get them to establish connections that will help them throughout their careers.

|

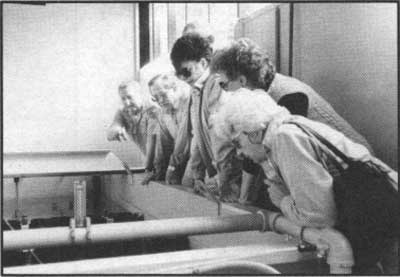

| Fig. 33 After 1980, when the funding base of the Parks Division was shifted from the gasoline tax-supported Highway Fund to General Fund monies, expansion and enhancement of the state parks came to a halt. In 1987, the State Transportation Commission named a special citizen advisory committee to prepare a strategic long-range plan aimed at setting priorities for development. In the two-year planning effort that followed, a path was charted to the year 2010, and the cost of maintaining existing facilities and meeting future demand was outlined. In the course of assessing needs, members of the State Parks 2010 Advisory Committee were pictured in 1988 inspecting the water supply plant at Jessie M. Honeyman Memorial State Park. From the left: Joe Davis, park manager; John Whitty, Lynn Newbry, committee chairman; Sandra Lazinka, Barbara Walker. They are accompanied by Charlotte Newbry, second from right. 1988. Monte Turner Photo. Oregon State Parks. |

|

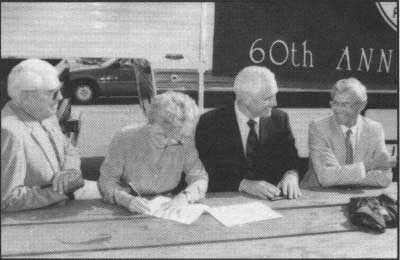

| Fig. 34 The vision for the future embodied in the State Parks 2010 Plan led Governor Neil Goldschmidt to propose a separate department under a Parks and Recreation Commission authorized to specialize in park matters and promote support for programs. The Oregon Legislature backed the proposal, and the Parks Department bill was signed into law as the high point of the agency's 60th anniversary ceremonies in Salem on August 2, 1989. The governor is joined by Secretary of State Barbara Roberts in formally approving the law while chief witnesses, 2010 Advisory Committee chairman Lynn Newbry (left) and State Representative John Schoon, one of the primary sponsors of the bill, look on. 1989. Oregon Department of Transportation Photo #V2313-17. |

|

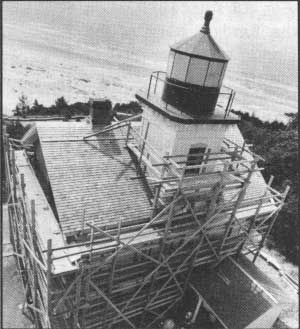

| Fig. 35. The old Yaquina Bay Lighthouse, constructed in 1871, is a feature of Yaquina Bay State Park at Newport on the central Oregon coast. Intermittently refurbished, the lighthouse was saved, once and for all, with encouragement of local historians when it was comprehensively restored in the years 1973-1975 and reopened as a public museum. It was among the first of a number of historic building restorations undertaken in state park units in the 1970s. 1974. Newport News-Times Photo. |

|

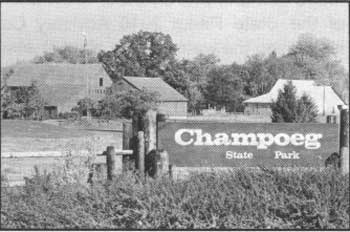

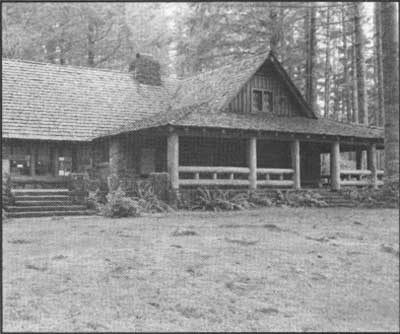

| Fig. 36. The Champoeg State Park Visitor Center, left, a model interpretive facility in the Oregon State Parks system, was opened for use in 1977. It was designed to be visually compatible with historic Willamette Valley barns and sheds in the surrounding landscape. 1986. Oregon Department of Transportation Photo #V1769-25. |

|

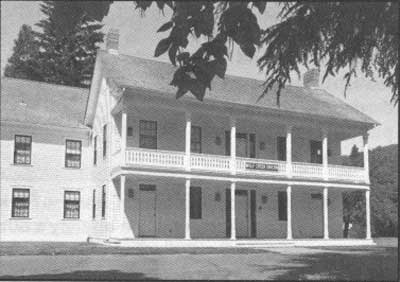

| Fig. 37. The focal point of Wolf Creek Tavern State Wayside in southern Oregon is a mountain pass hostelry built in the 1870s. An outstanding example of the type of double-porch way station traditionally associated with the state's early road network, the Wolf Creek Tavern was acquired and restored with federal assistance, beginning in concession in 1979. 1979. Oregon Dept of Transportation Travel information Photo #8871. |

|

| Fig. 38. Visitors to Silver Falls State Park in the foothills of the Cascade Range pause at South Falls on the trail network connecting 10 scenic waterfalls in the largest developed park in the state system. 1986. Oregon Department of Transportation Photo #M86-64-20. |

|

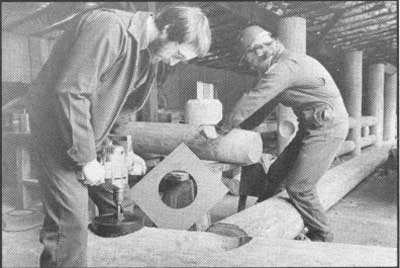

| Fig. 40. Downed trees from the forested terrain of Silver Creek Canyon were located to reproduce deteriorated members of the Silver Falls Lodge veranda during the 1980 restoration effort. Park ranger John Allen, left, and park aide Wally Judd use a combination of traditional hand tools and power tools to finish porch railing assemblies in the shop. 1980. Oregon Department of Transportation Photo #V605-18. |

|

| Fig. 39. Silver Falls Lodge and Concession Building was constructed in 1937 in the National Park rustic style as part of a large-scale program of betterment work carried out by Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees in Silver Falls State Park during the Depression era. An excellent example of the kind of well-crafted rustic architecture advocated by the National Park Service in forested settings, the building was rehabilitated by Parks employees in 1980. 1983. Ed Schoaps Photograph. Oregon State Parks. |

|

| Fig. 41. Representative of female employees who entered the management ranks of the field organization in the 1980s is Jeanette Gue Steed, shown here leading a tour at Champoeg State Park. Initially hired as a ranger, Jeanette moved into an interpretive specialist classification and, in due course, became assistant manager at Wallowa Lake and Cape Blanco state parks. 1983. Photographer unknown. Oregon State Parks. |

|

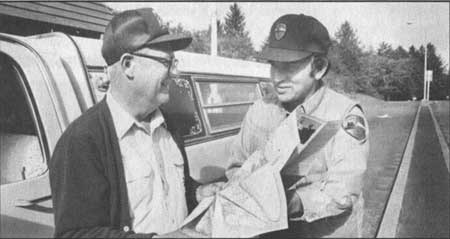

| Fig. 42. Assisting a camper at the registration booth in Fort Stevens State Park, Ranger II Larry Strenke represents the field personnel who, with park host volunteers, serve as the public's first point of contact in Oregon state parks. 1986. Oregon Department of Transportation Photo #V1779-33. |

|

| Fig. 43. Rock climbers regularly test their skills against the sheer face of the north ridge at Smith Rock State Park in the Crooked River Canyon of central Oregon. 1989. Or. Dept of Transportation Photo #V2260-29. |

|

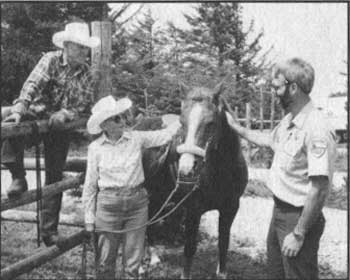

| Fig. 45. Paul and Lois Smith of the Pacific Northwest Appaloosa Club are among the growing number of volunteers who enhance state park operations. The Smiths, residents of Langlois helped build an equestrian camp in Cape Blanco State Park on the southern Oregon coast. They are pictured with Park Manager Mike Hewitt. 1988. Oregon Department of Transportation. |

|

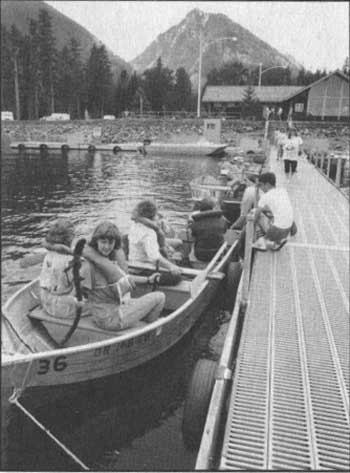

| Fig. 44. An alpine lake shaped by glacial action in the rugged Wallowa Mountains of northeastern Oregon is the primary attraction of Wallowa Lake State Park. In summer months, the concessionaire's boat docks are well used. 1988. Oregon Department of Transportation Photo #V2116-15. |

|

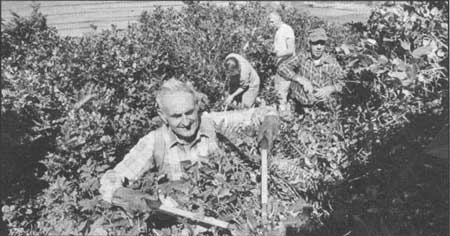

| Fig. 47. Volunteer work parties are recruited periodically to help build and maintain hiking trails in state parks. Pictured at Ecola State Park, clearing a segment of the Oregon Coast Trail, are retired Parks rangers Roland "Frenchie" LeCompte (foreground) and Mel Story (rear). They are assisted by Tom and Sue Boardman of Portland. 1988. Oregon Department of Transportation Photo #V2133-12a. |

|

| Fig. 46. The bicycle, hiking and equestrian trail at Banks-Vernonia State Park is a 21-mile linear park feature situated near the base of the Coast Range, on the west edge of the lower Willamette Valley. It is one of the few trails in the State Parks system to be developed from abandoned railroad right-of-way. 1991. Oregon Department of Transportation Photo #5-4-91-3. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

development3.htm

Last Updated: 06-Aug-2008