|

National Park Service

The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: An Administrative History |

|

|

Chapter Two:

NATIONAL PARKS AND STATE PARKS PROGRAMS: Upon submission to Congress of the original ECW legislation in March 1933, National Park Service Director Horace M. Albright began to prepare his staff for the additional workload. In a memorandum to Senior Assistant Director Arthur Demaray, Albright recommended that NPS officials compile a list of parks where conservation work was required. He specifically had in mind shoreline cleanup of Jackson Lake in Grand Teton National Park and Sherburne Lake in Glacier National Park, as well as roadside cleanup in Grand Canyon National Park and Glacier National Park. The NPS staff had master plans that outlined development requirements in most of the parks for a six-year period, and they used these plans to formulate the requested work programs. [1] Director Albright requested that park superintendents make estimates for road, trail, and facility construction. He also requested that the Branch of Engineering, Branch of Plans and Design, and Division of Forestry prepare an emergency unemployment relief forestation program. Since there was insufficient time to contact all parks for input, the work tasks were determined through analysis of the parks' five-year plans, fire protection plans, and preliminary 1935 estimates for forest protection and fire prevention measures. By early April the park superintendents were completing preliminary estimates on how best to utilize the ECW workers. Prior to the receipt of the requested estimates from the parks, the San Francisco NPS design office made its own estimates for cleanup work, fire hazard reduction tasks, erosion control projects, vegetation mapping, insect control, tree disease control, forest planting, reforestation, and landscaping projects for all the parks and sent them to Washington. The NPS Washington Office (forestry or planning division) had the right of approval for any project and defined limits on certain projects according to type of work, funds to be expended on structures and equipment, need for skilled labor, and impact on park land. If the type of work was deemed inappropriate, excessive expenditures of funds were required for material and equipment, a highly skilled work force was required, or the development was too extensive, the project would not be approved. As an example, truck trails were not to exceed 12 feet in width, while horse and hiking trails were not to be over 4 feet wide. In addition, the construction of firebreaks, lookout towers, houses, shelters, and fire guard cabins, the placement of telephone lines, and the development of public campgrounds were not to exceed $1,500 per structure without express authority from the NPS Washington Office. [2] On April 10 Director Albright designated his chief forester, John D. Coffman, to handle the details for the conservation program within the national parks, military parks, and monuments, and his chief planner, Conrad L. Wirth, to administer the state parks program. Albright had been designated by Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes to represent the department at meetings of the ECW advisory council. In turn, Albright designated Coffman to represent him at advisory council meetings that he could not attend; later this authority was extended to Conrad Wirth. Chief Forester Coffman was to prepare the departmental ECW budget, assign camps within the national parks and monuments, and allocate funding. In addition, he was responsible for preparing work instructions for parks and monuments and administering an inspection program. Wirth undertook similar tasks for the state parks program. In addition, Wirth was to report matters concerning the state parks to Coffman. In this regard, Albright telegraphed all state park authorities telling them that the Park Service was the designated agency to administer the ECW programs within state parks. He asked that they send representatives to a meeting in Washington on April 6. If this was not possible, he suggested they authorize S. Herbert Evison, secretary of the National Conference on State Parks, to represent them at the meeting. [3] NATIONAL PARKS AND STATE PARKS PROGRAMS: The administration of the Emergency Conservation Work in national parks and monuments was handled on two levels: The Washington Office approved projects and provided quality control; the park superintendents administered the overall ECW program within their parks and, on occasion, in nearby state parks. The superintendents submitted architectural plans to the chief of construction for either the eastern or western parks. The chief of the Eastern Division, Branch of Engineering provided supervision for all areas under NPS jurisdiction without regularly appointed NPS superintendents. [4] Plans for NPS undertakings affecting natural and cultural resources were reviewed by landscape architects foresters, engineers, and historical technicians to ensure protection from damage or overdevelopment. These experts also provided quality control for all NPS projects. Some of them were stationed in the Washington Office to act as consultants to park superintendents; others were placed within national parks and monuments, where they were assigned specific areas of responsibility. Park superintendents could draw from this pool of experts when work projects began. [5] The task for carrying out the ECW program belonged to the park superintendent. He was in charge of park work and was sometimes assigned specially designated areas of responsibility outside the park. The superintendent directed his staff in the preparation of work plans, prepared biweekly reports on the progress of the work, and prepared a project completion report at the end of each undertaking. This report described the cost of the project and gave a narrative description of the conditions before, during, and after the project. The park superintendent also hired and evaluated all ECW camp work supervisory personnel. The superintendent was encouraged to hold regular meetings with the camp superintendents and NPS technicians to discuss the progress of the conservation work. At first, the Washington Office informed the field officers on procedures through memorandums; later a handbook on ECW procedures was compiled and distributed to the field. [6] During the second year of the ECW many of these procedures were clarified. The superintendent of each national park and monument was required to formulate a work program for each ECW camp in his jurisdiction. Within parks, the conservation work was to be done exclusively on park lands or on lands contemplated for inclusion in other parks or determined necessary for protection of park lands. All cleanup, thinning, and stand improvement would be done under the supervision of foresters or landscape architects. [7] The state park parks program was administered from district offices. In an April 1933 meeting between Director Albright and Conrad Wirth, it was decided to divide the country into four administrative districts, with Washington as the East Coast headquarters, Indianapolis as the Midwest headquarters, Denver as the Rocky Mountain headquarters, and San Francisco as the West Coast headquarters. (The districts were also called regions during some periods of the 10-year state parks program administration.) Respectively, John M. Hoffman, Paul Brown, Herbert Maier, and Lawrence C. Merriam were appointed as district directors. Their offices began operation on May 15, 1933. To help Conrad Wirth administer the program, S. Herbert Evison was chosen as his assistant (see following organizational chart). [8] The district directors supervised the work in the various states, and their staffs evaluated work projects and recommended future projects. Staff inspectors were chosen from the landscape architect and engineering professions, and they were responsible for the progress and quality of the projects and for revising and perfecting design plans. There was one inspector for every five to seven camps, who remained in the field moving from one camp to the next. Every 10 days the inspectors submitted reports to the district offices and Washington. Based on Washington guidance, the inspectors were to discourage any undertakings that would adversely affect the natural character of the park and prevent those activities that would prove harmful to the native animals and plants. Ideally, they were to bring to the states information concerning good forest management practices and to promote high-quality development. The NPS Washington Office made the final determination on new state parks projects, new camps, requests for funding allotments, personnel matters, and land acquisition. [9] State ECW camps were administered by the state authorities, but the technical supervisors and project superintendents were paid out of federal funds. The states were given a specific allotment and were responsible for dividing these funds among the various camps under their jurisdiction. The Park Service assisted the states in drafting legislation necessary to the planning, development, and maintenance of their state park systems and with technical guidance and assistance. State parks work projects involved recreational development, conservation of natural resources, and restoration and rehabilitation of cultural resources. [10] NATIONAL PARKS AND STATE PARKS PROGRAMS: In 1933, as the ECW became fully operational, the Park Service began using ECW funds to hire supervisory foresters selected by park superintendents to supervise the conservation work. At the same time the central offices began hiring additional landscape architects, engineers, and historians to research, design, review, and inspect projects. In 1934 some of these appointments were converted to permanent positions, with the result that some people gained career positions in the Park Service. The auxiliary help hired by the Park Service continued to rise until in 1935 nearly 7,500 employees had been hired by the Park Service using ECW funds. Hiring then leveled off for two years and later slowly declined until the termination of the CCC in 1942. [11] In 1934 and later years Director Fechner authorized the temporary use of students during the summer months. The Park Service was allowed to recruit 135 students from college campuses to work in the Washington Office and in park areas. The Washington branch chiefs selected these student technicians, giving preference to students who had completed two or more years of college. The branch chiefs then gave the park superintendents the names and addresses of the students assigned to their parks; the park superintendents notified the Army corps commanders and the camp commanders as to the selected students. The students were subject to the same policies and procedures as regular CCC enrollees with minor exceptions. They were exempted from sending $25 of their $30 a month allotment to parents or dependents. Instead they were permitted to keep the full allowance to help defray college costs. Landscape architects, engineers, and architects were paid $75 a month instead of $30. The work assignment of the students was more technical and complementary to their college programs. Park superintendents were instructed to watch the progress of these students very carefully and to encourage them to select the Park Service as a career after completion of college work. The students selected were landscape architects, engineers, foresters, geologists, archeologists, historians, and science majors. They were assigned to complete historical research, archeological research, natural science research, mapping, and architectural design, besides conducting guided tours. [12] By 1938 the student technicians were paid as much as $85 a month and could be hired between June 16 and September 15. That year the four newly created Park Service regions were allocated 105 student positions. The remaining 70 student positions were in various branches in Washington, with the Branch of Recreational Planning and State Cooperation and the Branch of Operations being allocated the majority. Out in the parks, 11.3 percent of the former CCC enrollees were hired by the Park Service into technical jobs such as supervisory positions, facilitating personnel, and skilled workmen. [13] In June 1940 the Park Service operations staff consisted of 7,340 employees and of this number, 3,956 were paid out of Works Progress Administration, Civilian Conservation Corps, and Public Works Administration funds. As the relief funds were reduced, the Park Service continued to lose the people hired using these funds, and it became increasingly difficult to maintain and operate the parks and monuments in accordance with congressional mandates. The Park Service sought to alleviate the situation by increasing civil service positions; however, the personnel reductions, exacerbated by the manpower requirements of World War II, plagued the agency for years to come. [14] NATIONAL PARKS AND STATE PARKS PROGRAMS: With the commencement of the ECW program, a problem arose in NPS areas as to whether or not private lands could be purchased using ECW funds to adequately protect park resources. The question was perplexing enough to have United States Attorney General Homer S. Cummings halt a land purchase at Great Smoky Mountains National Park made with ECW funds. President Roosevelt resolved the difficulty on December 28, 1933, by issuing an executive order that permitted the Park Service to purchase private lands using ECW funds. The executive order specifically mentioned Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Colonial National Monument, and the proposed Shenandoah National Park and Mammoth Cave National Park as areas in which land purchases were permissible. In addition to these park areas, the National Park Service later purchased land in the proposed areas of Isle Royale National Park, Big Bend National Park, Everglades National Park, and Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Director Cammerer commented: [15]

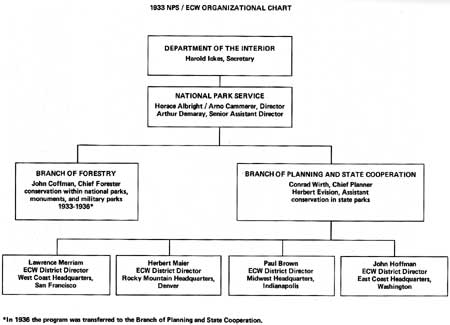

To further facilitate the ECW, President Roosevelt issued two executive orders in 1934 which authorized the expenditure of funds to purchase lands for conservation work. The National Park Service used this authorization to acquire additional lands for national parks and state parks projects. [17] 1936 CONSOLIDATION PROGRAM By 1935 the NPS Branch of Planning under the direction of Conrad Wirth had established eight regional (district) offices to help in administering the state parks program. These offices oversaw and approved the work of the individual state offices, provided quality control on state projects, and were responsible for certain budgetary and personnel matters within their jurisdiction. At the same time, the ECW program within the national parks and monuments was administered by the NPS Branch of Forestry. This produced a duplication of functions and personnel by the two branches, requiring NPS Director Cammerer to discuss with the branch chiefs how best to eliminate the problem and more efficiently administer the ECW program. Since the ECW state parks program was the larger of the two, Director Cammerer, in consultation with Wirth and Coffman, decided to transfer the ECW national parks and monuments program from the Branch of Forestry to the Branch of Planning and State Cooperation. The effective date for the beginning consolidation was set for January 15, 1936; it was to be completed by June 1, 1936. [18] With the presidential decision to reduce the ECW program in scope and to curtail funds in the fall of 1935, NPS officials were forced to find ways to reduce its administrative costs. On January 26, 1936, a special committee composed of Washington officials and park superintendents met to explore ways to remedy the situation. The majority of the committee members did not want to regionalize the ECW program until the National Park Service itself was regionalized. (This Park Service reorganization had been discussed since the successful regionalization of the ECW state parks program in 1933.) Opposed to this view were Washington officials Conrad Wirth, Verne Chatelain, and Oliver G. Taylor, who advocated an immediate partial regionalization of the ECW national parks program. Wirth presented this minority view in a January 26, 1936, letter to NPS Director Cammerer, who, after studying the committee's report and the letter, decided to implement Wirth's proposals. Starting in May 1936 the national park superintendents continued to submit their ECW projects to the Washington office for approval, but all project inspection work and liaison duties with the Army became the responsibility of ECW state parks regional offices (as the national parks regions were not yet established). The second phase of this plan in the last half of 1936 was to consolidate the number of ECW regional offices from eight to four with each region having from two to five suboffices, which were known as districts. Each of the regions was assigned a complement of inspectors made up of engineers, landscape architects, foresters, wildlife experts, geologists, archeologists, and historians to maintain the quality of the work performed. Secretary of the Interior Ickes wanted to see all ECW work administration carried out by the NPS regional offices when they were established. [19] The reduction of the ECW program facilitated the speedy transfer of supervision of the national parks and monuments program from the Branch of Forestry to the Branch of Planning and State Cooperation. By February 1936 the Branch of Planning was placed in charge of all matters relating to the ECW camps, and the state parks inspectors were monitoring projects in national park and monument areas. [20] Also in early 1936, the procedure for ECW work was clarified. In state park areas, an ECW work application could start when a general management plan was completed and approved. Then the application would be written and submitted to state offices, and in turn to regional offices where technicians checked it over and the work would be classed as A, B, or C to indicate regional priority. This compiled list would then be sent to Washington where the Park Service director, upon recommendation by his staff, would give preliminary approval to the projects. The approved application would be sent back to the field where the park superintendent or state park official would be notified as to which projects had been approved and which camps could begin working on them. Detailed plans for projects, including estimated time, labor, and money necessary for completion, were then submitted to the Washington Office for final approval. Once approved, funds were made available to begin contracting for materials, with all contract change orders over $300 being sent to Washington for approval. If the original funding estimate for a project proved inadequate, a supplemental funding application would be sent to Washington. Conrad Wirth had developed a "48-hour system" by which the original application and requests for additional allocations of money would be either approved, held in abeyance, or disapproved within 48 hours after reaching Washington. The field officers were notified of the decisions. The "48-hour system" applied only to state park projects and had been used experimentally in 1935. Between 1935 and 1936 over 90 percent of the applications were processed within the prescribed time limit, and few complaints were received concerning the procedure. [21] IMPACT UPON NPS REGIONALIZATION Wirth's regionalization of the ECW state parks program in 1933 set a precedent for the eventual regionalization of the National Park Service. In 1934, Wirth was selected by Director Cammerer to discuss the subject of NPS regionalization at a park superintendents conference. The superintendents believed that regionalization would merely place another layer of bureaucracy between them and the NPS director. [22] In 1936 when the Park Service set about to reorganize the ECW state parks program into four regions, Director Cammerer wanted these offices located so that if the Park Service went to a regionalized basis the ECW regional offices could be merged with the NPS regions. On June 1, 1936, Secretary of the Interior Ickes publicly announced that the Park Service would be regionalized. That fall the National Park Association attacked the proposed regionalization plan on the grounds that ECW personnel would assume key positions in the regions and that the standards of the Park Service would be lowered to those of the state parks program. Secretary Ickes and Director Cammerer dismissed these charges as being unfounded and added that the higher positions would be assigned to regular Park Service employees and not to ECW administrators. In August 1937 when the NPS regionalization was implemented, some of the regional positions were assigned to people with ECW backgrounds. The four National Park Service regional offices corresponded identically with the reorganized ECW offices except that in the newly created region three, the NPS headquarters was located in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and the ECW headquarters was in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. [23] ADMINISTRATIVE RELATIONSHIPS The magnitude of administering the ECW program brought the National Park Service in close working contact with the Departments of War, Labor, and Agriculture, as well as with other bureaus within the Department of the Interior. Roosevelt had originally intended that the Department of the Interior and the Department of Agriculture would jointly administer the entire program. It soon became apparent, however, that to implement the program as quickly as he wished, an effective recruiting system would be required. The Forest Service and Park Service did not have enough manpower or expertise to recruit enrollees or operate the camps 24 hours a day. This brought the Departments of Labor and War into the program as full participants. The Army and War Department The Army wanted to be of assistance during the 1933 mobilization of the ECW but expressed reluctance to cooperate with other government agencies. President Roosevelt overcame these misgivings and convinced the Army to supply equipment and men for operating the conditioning program and administering the camps. The camp administrator was called the camp commander and he was assisted by a supply sergeant, a mess sergeant, and a cook (see chapter 3). The Army at first set up the camps using regular Army officers, but early in 1934 these men were replaced by reserve officers. (At the same time the Army replaced noncommissioned officers in camp personnel positions with men chosen from among the camp enrollees). The War Department wished to rotate commissioned camp officers to different camps every few enrollment periods so that they would not assume they had permanent positions at specific camps. The Forest Service and Park Service were concerned about this policy because they believed that the longer the commissioned camp officers could remain in place, the more proficient and knowledgeable they would become about their work and the needs of the park or forest area. Within the ECW advisory council, a struggle arose among the Park Service, the Forest Service, and the Army over the question of camp officer rotation. In 1934 the Forest Service and the Park Service joined forces to oppose this Army policy. Colonel Duncan K. Major, the Army representative in the advisory council, responded that the rotation policy had not reduced the camps' work efficiency nor had it adversely affected camp morale. Colonel Major ended his argument by stating that neither the National Park Service nor the Forest Service could dictate Army policy. This disagreement continued over the next several years. [24] The rotation question was but one of several conflicts between the Army and the Park Service over daily camp operations. Another source of contention involved the balance between men needed for camp maintenance and those required for project work. Gradually, the army camp commanders began to hold back more and more enrollees from daily project work for housekeeping duties around the camp. The Park Service superintendents complained that such tasks constituted unnecessary ''overhead'' and detracted from the primary mission of performing conservation work. After several months of disagreement the Army and the Park Service agreed in August 1933 that camp commanders could keep 23 to 26 men around camp for housekeeping duties. [25] The Army also opposed the use of locally employed men (LEMs). These people were hired by the National Park Service and were not under Army control. Park Service officials saw the LEM program as a way in which men skilled in conservation work could be hired. The army officials were uncomfortable with this program and it remained a source of irritation until the termination of the CCC program. [26] As the summer of 1933 drew to a close, Army and NPS officials recognized that conflicts between the camp commander and park superintendent would occasionally arise. Procedures were established for conflict resolution, which emphasized the need for settlement on the local level if at all possible. Such a system emphasized the need for the park superintendents and the camp commander to have a close working relationship. If problems could not be worked out on the camp level, the park superintendent would then contact the liaison officer or corps commander at the appropriate army corps headquarters. If a satisfactory solution could still not be reached by both parties at this level, they could notify their superiors to bring the matter up during a meeting of the advisory council. The advisory council decision would be passed down to the appropriate camp officials. Only the most difficult matters went through the entire process. [27] The issue of establishing side camps away from the main 200-man camps was the most difficult conflict to resolve. The purposes of the side camps were to construct trails, build firebreaks, install fire lookouts, provide emergency fire details, and control tree disease in areas that were inaccessible to large groups. In April 1933 the Forest Service requested that President Roosevelt permit the use of such camps to do some of the proposed conservation work; the request was turned down. In June, Robert Stuart of the Forest Service and Horace Albright of the Park Service again recommended the use of side camps to accomplish work. They argued that without such camps up to 40 percent of the conservation work for parks and forests could not be accomplished. The Army opposed this idea. There were not enough men to supervise the enrollees in these camps and they feared a high desertion rate. Also the Army pointed out that such camps would add 10 percent to the food costs for the camps. ECW Director Fechner concurred with the Army's position, but on July 19 President Roosevelt ruled that the side camps could begin on a one-month trial basis. [28] On July 22 Secretary of War George H. Dern sent a message to all corps area commanders on the procedures for setting up the side camps. No more than 10 percent of the camp's complement could be assigned to side camps. The men would work in these camps from Monday through Friday and return to the main camp on weekends. The Park Service would be responsible for providing shelter, transportation, and supervision for their side camps. The Army camp commander and the corps area commander had to give formal approval before the park superintendent could establish a side camp. Within two weeks of the start of the experiment, 300 side camps were established by the Forest Service and Park Service, and the 10 percent limit was exceeded. Chief Forester Stuart and NPS Director Albright reported to Director Fechner in August that the experiment had proven to be a great success and that the morale in the side camps was high, with no desertions. The side camp was subsequently made a permanent feature of the ECW program. President Roosevelt permitted the Army corps area commanders to determine how many men from the main camp could be assigned to work in side camps. [29] Army officials again felt that their supervisory role was challenged when the question of how to deal with safety issues was raised. The Army held that it should be the sole determiner on safety matters, while the National Park Service wanted to be responsible for on-the-job safety. The Army compromised by agreeing to the formation of a safety committee composed of the camp commander, an NPS representative, and the Army medical officer. [30] In May 1934 Conrad Wirth further irritated Army officials by suggesting that ECW enrollees within NPS camps be given a meritorious service certificate after completion of their term of duty. Colonel Major stated that the Army was opposed to such an action unless the certificate was given to all ECW participants and not just NPS camp enrollees. Wirth, supported by Frederick Morrell of the Forest Service, argued that the Army discharge form was inadequate as a record of service and an aid in seeking employment. Colonel Major maintained that the Army was the sole administrator in charge of personnel matters and had exclusive authority to issue any certificates. The Army was able to forestall the issuance of the NPS certificate until May 1935 when Director Fechner approved a modified version of the concept. The National Park Service was allowed to issue a certificate; however, the camp commander was not required to sign it and all reference to the Army was removed from the document. [31] In 1935 Wirth and the Forest Service representative brought up the side camp issue again in the advisory council. The Park Service observed that conservation projects in mountainous western park areas could best be accomplished by using small side camps and requested that the 10 percent ceiling on side camps be increased. The Army agreed to let the corps area commanders increase this ceiling above 10 percent. In return, Colonel Major requested that the number of LEMs hired by the Park Service to supervise these camps be limited to 16 per camp. In this way the Army hoped to control the number of side camps. Further, the Army wanted all these men to be considered part of each state's ECW hiring quotas. Fechner and the Park Service agreed to both of these stipulations. [32] The old conflict with the Army concerning the rotation of camp officers was revived on May 13, 1937, when the Army issued an order requiring reserve officers to remain on ECW duty for a total of only 18 months, with 25 percent of all the officers being granted special permission to serve for two years. The order further granted medical officers the right to remain on duty for three years. The date set for full implementation of that order was December 31, 1937. Both Fechner and the representatives of the Park Service and Forest Service reacted negatively, believing that it would prove detrimental to the work program. Director Fechner discussed the matter with President Roosevelt and gained his support in opposing the Army. On July 20 the Army issued a modification to the original order that allowed indefinite retention of 50 percent of the reserve officers in each corps area except for medical officers and chaplains. The next day during a meeting of the advisory council, the Army representative announced plans to replace all reserve officers in camps by July of 1938. The Park Service saw this action as a mistake, but could do nothing more to prevent it. [33] During 1938 Director Fechner approved regulations that prohibited park superintendents from making fire inspections of the camps under Army jurisdiction. The park superintendents believed that since the camps were on Park Service property, they were responsible for fire safety in the camps. Even after Director Fechner's ruling, some park superintendents (such as at Vicksburg National Military Park) were able to obtain permission from the Army camp commander to inspect the camps for fire hazards. [34] ADMINISTRATIVE RELATIONSHIPS: In July of 1937 Director Fechner announced to the CCC advisory council that he intended to transfer to his office the liaison officers then being hired by, paid by, and working for the technical agencies (the Forest Service and Park Service). The Departments of Agriculture, War, and the Interior feared that this was a further concentration of power in the director's office. The bitter opposition to Fechner's proposal led him to solicit support from the president. Roosevelt responded by issuing an executive order in September that directed the secretaries of war, interior, and agriculture, and the administrator of veterans affairs to cooperate with the director of the CCC. Despite this directive, the various agencies remained reluctant to give full support to all of Fechner's policies. In June 1938, Fechner drafted a letter for the president's signature that would give the director clear authority to initiate and approve all policy matters. President Roosevelt refused to sign the letter until November, when Fechner threatened to resign. Fechner then announced to the advisory council that his decision on policy could only be superseded by the president. This pronouncement met with silence in the advisory council, and the secretary of the interior later accused Fechner of usurping responsibilities that had been delegated to the Department of the Interior. [35] Fechner continued to consolidate and centralize functions of the CCC. In 1939 he upset the technical agencies by proposing that a chain of central machine repair shops be established directly under his office's control. Wirth declared that such a plan would adversely affect the CCC program and asked Fechner to reconsider his decision. He further stated that if Fechner's decision was not reversed, the Department of the Interior would submit the matter to the president. Secretary of the Interior Ickes added that the whole question should be investigated by the Bureau of the Budget. Despite the open opposition by the Departments of War, Agriculture, and Interior, Fechner proceeded. He next received presidential approval to have the Selection Division removed from the Labor Department and placed in the director's office. After Fechner's death at the end of 1939, Secretary Ickes wrote to the director of the Bureau of the Budget that the time had come to abolish the CCC director's office He proposed that the entire CCC program be jointly administered by the Departments of Agriculture and Interior, which would assume the duties of the War Department and those of the CCC director's office. President Roosevelt disapproved the plan and appointed James McEntee as the new CCC director. [36] ADMINISTRATIVE RELATIONSHIPS: The Park Service and the Forest Service often cooperated on matters of mutual concern in the ECW advisory council; however, they did have areas of disagreement. The state parks program was one of the main areas of misunderstanding between the two agencies. State parks camps were administered by the Park Service or by the Forest Service, depending on criteria agreed to on May 10, 1933. If 50 percent of the work projects were on state forest lands and not of a resource management nature, the camps would be under the Park Service. Otherwise, the camps would be administered by the Forest Service. The Park Service agreed to consult the state forester before submitting work proposals on certain projects. The agencies agreed to exchange lists of camps to determine whether they should be subject to Park Service or Forest Service administration. In one of these initial exchanges, Conrad Wirth found that 28 of 144 camps being proposed by the Forest Service properly belonged in the state parks program and they were transferred to the Park Service. [37] The conflict between the two agencies partially came from performing similar work--such as fire and forest protection measures. The approach and execution of the work, however, differed as explained by Wirth in the following memorandum to the Forest Service:

Such a fine distinction between Park Service and Forest Service work, along with a desire on the part of the Forest Service to do park work, resulted in a series of conflicts between the two agencies during the CCC period. In 1934 the Forest Service presented the Park Service a rather startling memorandum for its approval. The memorandum, if accepted by the Park Service, would have permitted the Forest Service to undertake the same type of recreational development in national and state forests as was being done under the Park Service in the state parks program. The Park Service refused to sign the memorandum on the grounds that this would sanction the Forest Service's performance of functions that properly belonged within the Department of the Interior. Again in 1934 the Forest Service transferred some camps to NPS jurisdiction, but expressed concern to the secretary of the interior that the Park Service was attempting to lure some of the Forest Service foresters and foremen from these camps into the Park Service. Wirth, following the secretary's instructions, issued a warning that Forest Service employees could be hired by the Park Service only after Park Service officials had secured the consent of the regional or state forester. On the other side, Park Service field officers complained that the liaison officer positions in Army corps headquarters were filled with Forest Service people who favored that agency over the Park Service. [39] Problems again arose between the Forest Service and Park Service over the question of park work when on February 7, 1935, Director Fechner approved a memorandum authorizing the same work done in state parks to be undertaken in state and national forests. The Park Service, which had earlier refused to sign the same memorandum, expressed concern to Fechner over his approval of the Forest Service's proposal. Fechner sent a letter to the Forest Service and the Park Service on April 8 asking the two agencies to meet and work out any differences on the work question. The two agencies met but did not come to any agreement. [40] On May 22, acting NPS Director Arthur Demaray outlined the department's position regarding the Forest Service in a letter to Secretary of the Interior Ickes. Demaray made the following points:

The Secretary of the Interior's office slightly rephrased the points made by the National Park Service and sent a letter to Fechner requesting that he rescind the authorization given to the Forest Service. Director Fechner met with representatives of the National Park Service and Forest Service in an effort to reach some accord. Neither agency would agree to any compromise and Fechner refused to rescind his authorization to the Forest Service. For the next several years the Forest Service continued to do "park" work and the National Park Service continued unsuccessfully to object to this practice. [42]

ADMINISTRATIVE RELATIONSHIPS: On April 1, 1937, Robert Jennings, head of the accounting division of the Park Service, received a telephone call from the Army finance office asking for Reno E. Stitely, chief of the voucher unit, to pick up the payroll checks for CCC men at Shenandoah National Park. Jennings was surprised by this request since pay normally was sent to the camps for distribution and not to his office. He, however, had the presence of mind to go to the finance office and take the checks. This was the beginning of the most sensational case of embezzlement in CCC history. An investigation was begun immediately and culminated in the arrest of Stitely on April 27 for falsifying 134 payroll vouchers comprising 1,116 checks which amounted to $84,880.03. [43] The embezzlements began in 1933 when Stitely was named in a letter from the director of the Park Service to the Army Finance Office as being authorized to approve bills for pay. Using this authority Stitely forged the name of the superintendent of Shenandoah National Park to a letter which authorized him to sign for payroll vouchers. Stitely created fictitious ECW personnel, submitted falsified payroll vouchers for them, picked up their payroll checks, forged their names on these checks, and deposited the checks in various savings accounts around the Washington area. He used the money to buy cars, a house, and stocks, and to throw lavish parties. After Stitely was caught, it was alleged that he had created "dummy" CCC camps. Actually, his fictitious people were assigned to no particular camp. On January 7, 1938, Stitely pleaded guilty to nine charges of forgery and embezzlement, was sentenced to 6-12 years in prison, and fined $36,000. Senator Gerald P. Nye (North Dakota) of the Senate Public Lands Committee held hearings on the Park Service and War Department accounting systems in an effort to prevent such incidents from recurring. This type of fraud remained an isolated incident, but it left a blot on the fiscal records of the National Park Service. [44] |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

paige/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 29-Feb-2016