|

National Park Service

The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: An Administrative History |

|

|

Chapter Three:

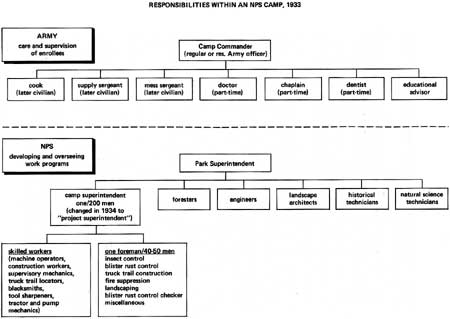

Each year that the CCC existed the programs and projects within camps varied. There were also seasonal and regional differences in the camps as the program evolved based on administrative and legislative changes. ADMINISTRATION Administrative authority in the ECW/CCC camps was divided between the Army's camp commander, who supervised all the activities of enrollees within the camps, and the park superintendent, who coordinated all project work accomplished. The camp commander was a regular or reserve army officer; he was assisted by a supply sergeant, mess sergeant, and cook. Beginning in 1934 these assistants were replaced by civilian employees who were also supervised by the camp commander. The Army was also responsible for providing a part-time doctor, dentist, chaplain, and, later on, a full-time educational advisor. These men undertook the care and supervision of enrollees in the camps. The park superintendent was responsible for overseeing and developing the work program for the camps. To set up daily work schedules, a camp superintendent was hired for each 200-man camp in the park. Daily work crews were directed by foremen assigned to supervise the work of 40- to 50-men crews. These foremen were classified according to tasks performed, such as insect control, blister rust control, truck trail construction, fire suppression, landscaping, blister rust control checker, and miscellaneous projects. For technical supervision, foresters, park engineers, landscape architects, and historical technicians could be hired. These people would sometimes work for several camps in several national and state park areas. Historical technicians, park engineers, and landscape architects were hired with the concurrence of the NPS chief historian, chief engineer, and chief architect, respectively. Park superintendents could hire skilled workers such as machine operators, construction workers, supervising mechanics, truck trail locators, blacksmiths, tool sharpeners, and tractor and pump mechanics when appropriate (see attached chart). [1] The park superintendent was responsible for the formulation of the work programs, inspection of the work, and keeping the camp superintendent on his work schedule. The activities of the historians, engineers, architects, foresters, and nature experts were coordinated and directed by the camp superintendent. In some cases, the park superintendent developed programs that extended beyond park boundaries into state and recreational demonstration areas. State parks officials formulated their own work programs, which were submitted to the Park Service for approval. The Park Service supplied the states with guidelines for what type of work could be undertaken, procedures for establishing camps, regulations governing fiscal transactions, and a variety of other matters. The states chose their own staffs analogous to the Park Service's staff to administer the work programs in the camps. [2] In 1934 the nomenclature and definition of certain supervisory positions were changed. The Park Service redesignated the camp superintendent to be the project superintendent. The duties defined for this person included the coordination and supervision of civil engineering, construction, maintenance, and developmental projects for a single camp and management of the expenditure of government funds for the work projects of several camps. Under the project superintendents were classifications of foremen assigned various duties in supervising the daily work. A number of the first-period enrollees were selected for the foreman and supervisory positions in the second period of the program. [3] By 1939 the potential staff positions for a CCC camp had expanded to include a commanding officer, an assistant commanding officer, a staff doctor, a senior leader and assistant leaders, a company clerk, a storekeeper, a supply officer, an infirmary attendant, a steward, first and assistant cooks, a chauffer, a mechanic, an educational adviser, and an assistant educational adviser. Not all camps had people in all these positions. Ten men from each camp could be used by the park for educational, guide, and public contact work. If the enrollees worked on Saturdays, Sundays, and holidays, they were to be given compensatory time. Enrollees selected for these positions were to be volunteers, have public speaking ability, use good English, be neat in appearance, and have courteous manners. [4] To monitor the progress of the work, a number of progress reports were required. Camp inspectors were to provide weekly reports to the district offices on the camps visited. The park superintendent was to submit a weekly report on the work in his park, along with statistical data on camp strength, health, and highlights. He also prepared a biweekly narrative report of activity. By August 1933 the requirement for this biweekly report was changed to make it monthly. When the work program was being formulated, the superintendent was required to send copies to the Park Service Branch of Engineering and Branch of Plans and Design in Washington and to the Forestry Division in Berkeley. The camp superintendent was to compile bimonthly progress reports and a narrative construction report upon the completion of each project. [5] The precise location of camps in national parks and monuments was the responsibility of the Army and the Park Service. At first, all camp locations were to be approved by President Roosevelt; later that authority was delegated to Director Fechner. The camps were to be located on NPS lands near the work projects. Other requirements for campsite selection included their proximity to railway and highway, the attitude of the local populace, the availability of water for the campsite, and the availability of lumber and other building materials. After the Park Service officials selected a suitable site, Army officials would make an inspection. If the Army officials did not find the site satisfactory, they would request the director to disapprove the camp. In an attempt to decentralize the camp selection process, Director Fechner on May 22, 1933, announced that camps could be moved up to 25 miles from their original site without Washington approval. Later, the camps could be located on private lands leased by the Army. [6] CAMP DESCRIPTION The early camps often were army tents, which were gradually replaced by more substantial wooden structures. Most of these structures were designed to last for only 18 months, and dismantling and reerecting them proved costly. In the spring of 1934 the Army designed a sturdy building with interchangeable parts that was fabricated for easy construction and could serve as an administrative, recreational, mess, or barracks facility. In addition, the structure was inexpensive, comfortable, weatherproof, easily transportable, and came in panels for easy construction. This type of building was mass produced in 1935. In 1936 Director Fechner ordered that all future ECW camps be of the prefabricated portable variety. By the end of the decade approximately 20,000 prefabricated buildings were used in 1,500 locations. A standard camp was formed in a rough "U" shape, with recreation halls, a garage, a hospital, administrative buildings, a mess hall, officers' quarters, enrollee barracks, and a schoolhouse, all constructed of wood; it numbered approximately 24 structures. Each building fronted a cleared space that was used for assemblies and sports activities. The exteriors of the structures were sometimes painted brown or green, but more often the wood was creosoted or covered with tar paper. Some camps were wired for electricity. [7] In 1939 the CCC director revised the standard plan for the camps. The new camp was also to consist of 24 structures, but with a separate room or tent for the camp superintendent and separate recreational and dining areas for the supervisory personnel. In some camps these standards were met or exceeded; in others they were never achieved. The exteriors of the buildings were to be painted or stained only to prevent deterioration, and only those portions of the building subject to damage were to be treated with any preservatives. This was done to keep construction costs down. [8] In the summer of 1933 side camps, which were usually just tents, were established away from the main camps. Side camps were set up when, for example, a job was at such a distance that a long trail trip would be necessary each day. Another use of side camps was during dangerous fire weather when small groups of enrollees were placed in strategic areas where they could keep watch for forest fires and act quickly to extinguish the fires. Crews stationed in these side camps were rotated so that the youths could participate in all camp activities. [9] ENROLLMENT When the ECW program began in 1933, applicants were selected by the Department of Labor for the first enrollment period. Prior to the first enrollee selection, quotas were established for each state and federal agency. State authorities would set local quotas and designate a local selecting agency (the Labor Department or the Veterans Administration). This local agency was to review the relief lists and make a preliminary selection of eligible youths. The Welfare representative would then set up an appointment to meet with the youth and his family to discuss ECW work and offer the youth an application form to fill out. The welfare representative was to determine through the application and interview that the youth was between 18 and 25 years old with no physical handicap or communicable disease, unemployed, unmarried, and a United States citizen. Since this was designed to be a relief program, the applicant had to be willing to send a set portion of his pay to his family. The selecting official was encouraged to pick applicants who were clean-cut, ambitious, and willing to work. In this regard, it was suggested that applicants with backgrounds as Boy Scouts or Scout leaders or with some type of training in woodcraft be given preference. [10] Despite the seeming stringency of the selection process, those selected were, on occasion, less than the ideal. A participant in the program described his fellow workers in the following manner:

After an applicant was accepted, he was sent to an Army recruiting station where he was given a preliminary physical examination. He was instructed to bring a suitcase with his toilet articles, one good suit for excursions away from camp, and any other items he might require during the six-month tour of duty. If he played any small musical instrument--such as guitar, mandolin, ukelele, or harmonica--he was encouraged to bring it for use during recreation periods. If he passed the preliminary physical examination, he would then be sent to a conditioning camp. There he would be given a final physical examination and inoculated against typhoid, paratyphoid, and smallpox. [12] Then the applicant would be given the "Oath of Enrollment" which went:

This oath was administered at the time of the preliminary physical examination if the enrollee was to be sent directly to the work camp. [14] Those who went to a conditioning camp usually remained there for two weeks. The camps were mostly on military installations. The conditioning process included a regimen of calisthenics, games, hikes, and certain types of manual labor. To avoid criticism that the ECW was preparing American youth for the military, no military drill or "manual of arms" was conducted. While at this camp, the recruits were issued variety of Army surplus shoes, trousers, and shirts. Later the youths were issued blue denim work suits, caps, and a modified Army dress uniform which consisted of sturdy black shoes, woolen olive drab trousers and coat, khaki shirts, and black necktie. The shirts had chevrons on the sleeves that resembled those worn by noncommissioned Army officers except that the insignia of rank was red instead of khaki. While at the conditioning camp, the new recruits were observed for their ability to do hard labor and comply with camp regulations. [15] The original pay plan allowed each of the enrollees to keep $5 for personal expenses and send $25 to his family each month. After President Roosevelt modified the organizational structure by executive order on June 12, 1933, the camp commander was allowed to select up to 5 percent of the camp complement to act as camp leaders; these leaders received a cash allowance of $45 (with a set portion going to their family). Those selected did some administrative tasks and could be used in overseeing project work. Another 8 percent of the camp company could be designated as assistant leaders and receive an allotment of $36 a month (with a set portion going to their family). Later the number of assistant leaders was raised to 10 percent. [16] There were several categories for enrollees; the largest was for young men between 18 and 25 years of age who were known as "Juniors." In mid-1933 President Roosevelt issued executive orders to allow war veterans, Indians, LEMs, and residents of American territories to enter the CCC. In some cases, the territorial and Indian recruits were allowed to remain at home and perform work projects during the day. The LEMs were required to take a physical and be formally enrolled by the Army though their work was for the NPS superintendents. Each camp was allowed eight to 12 LEMs with an additional 16 permitted when the camps were moved from one location to another. These LEMs served as foremen and skilled workers in the camps. [17] The recruitment rules were changed in 1938, primarily because those men eligible for the CCC were choosing better paying jobs. In September 1937 the average number of men per camp stood at 186. By June of 1938 this number had dropped to 142--well below the official designation of 200 men per camp as recruitment quotas were not met. The Hawaii National Park camp had been granted permission to enroll youths as young as 16 on an experimental basis. After considerable discussion in the CCC advisory council, however, it was decided to set the minimum age for recruits at 17. Instructions were sent out that these youths were to be selected because of their independent disposition. Parents were urged by the welfare representative to write cheerful and encouraging letters to the enrollees during their first weeks at camp to prevent desertions. The practice of placing the new recruits in a conditioning camp was discontinued in favor of sending the enrollees directly to the work camps, where they were assigned less strenuous tasks at first and more difficult ones as they became accustomed to camp life. An older enrollee would be assigned the responsibility of educating the recruit in the ways of the camp. These measures were taken to raise morale and lower the desertion rate. [18] On January 1, 1941, a CCC enrollee could receive $8 in cash per month, with another $7 per month placed in a savings account until he was discharged. The remaining $15 would be sent to his dependents. Each 200-man camp was permitted to have one senior leader, nine leaders, and 16 assistant leaders taken from the camp complement, who were paid a higher salary than the regular enrollees. [19] When the CCC program was terminated on July 1, 1942, the enrollees were sent home and the camp structures were either demolished or used for other purposes. After the program was ended, the American Youth Commission took the statistics gathered during the program to make a composite of the characteristics of the average enrollee. They described him as

It is unlikely that all, if any, of the CCC youths fit this stereotype, yet they probably shared at least some of these characteristics. When they left the CCC, they were healthier, stronger, more confident, and better able to earn a living. The CCC was an exciting experience that more than 2-1/2 million young men would remember for a lifetime. [21] DAILY ROUTINE The enrollees' workday began at 6:00 a.m. with reveille. The youths then had half an hour to dress and prepare themselves for the day's work. This was followed by 15 minutes of calisthenics and a hearty breakfast of fruit, cereal, pancakes or ham and eggs, and coffee. After breakfast, the enrollees made beds, cleaned barracks, and policed the grounds. By 8:00 a.m. they were either at or on their way to work. They would work until noon, when the crews stopped for a one-hour lunch. Sometimes a hot meal was provided, but most often lunch consisted of sandwiches, pie, and coffee. The youths then worked until 4:00 p.m. , when they were transported back to camp. The maximum work period was eight hours a day and 40 hours a week. Sometimes crews worked on Saturdays to make up for days lost during the week due to inclement weather. [22] Once the youths returned from work, they could engage in such recreational activities as reading, baseball, football, basketball, boxing, volleyball, pool, table tennis, horseshoes, swimming, and fishing, with tournaments between barracks often arranged. The park might purchase the recreational equipment, hold fund raising activities for buying the equipment, or solicit items from local groups. At Rocky Mountain National Park, the staff put on a minstrel show in the village of Estes Park to raise money to buy athletic equipment for the camps. Occasionally, camp officials organized bingo games, arranged dances with young ladies from nearby towns, presented plays, and had musical shows. Enrollees sometimes participated in historical pageants and theatrical performances to provide entertainment for themselves and for people from the local communities. The official newspaper of the CCC was "Happy Days" and copies were distributed to every camp. In addition, almost every camp published its own newspaper or newsletter, which appeared at more or less regular intervals. In 1937 the Park Service conducted a fire prevention poster contest opened to all CCC camps supervised by the Park Service. The winners of the first three places were brought to Washington where they drew the final color plates under the supervision of NPS artists and designers. In other camps spelling bees and singing contests were instituted to raise camp morale. [23] Each camp had a library of approximately 50 books--adventure stories, mysteries, westerns, science fiction, forestry, travel, history, natural science, athletics, biography, national parks, and miscellaneous subjects. In certain areas, the library was moved from one camp to another. Also such periodicals as Life, Time, Newsweek, the Saturday Evening Post, Radio News and the Sears-Roebuck Catalogue were popular. Certain publications, including The New Republic and the Nation, were banned from camps because they were considered subversive. Further, critics charged that camp officials provided books which pandered to popular taste and lacked literary merit. [24] Between 5:00 and 5:30 p.m., the recruits changed into dress uniforms and presented themselves for the evening meal--fresh vegetables, bread, fruit, and desert. During the first year of the CCC, the ration cost per man per day was approximately 37 cents. The food was plain, but was served in large quantities. [25] After class (see discussion below on training and education), enrollees could do as they pleased for the remainder of the evening. At 9:45, camp lights were flashed on and off and the youths prepared for bed. Camp lights were shut off at 10:00 p.m., with taps blown 15 minutes later. At 11:00 p.m. the camp commander made a bed check to see that all enrollees were present. This ended the day's activities. [26] Daily routine changed on weekends. On Saturdays, unfinished work projects were completed. If such work was caught up, the day was spent cleaning and improving the campsite. Afternoons were left for recreation and in the evening camp members were occasionally allowed to go into nearby towns for a dance or movie. On Sundays, religious services were held and the youths could go fishing, swimming, or just relax around the camp. In addition to Sundays, the camps did not work on New Year's Day, Washington's Birthday, Memorial Day, Independence Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas, or on other holidays of the Jewish, Catholic, Greek Orthodox, or Protestant faiths. [27] A recruit remained in the CCC camp for six months unless he received an offer of permanent employment or some extraordinary circumstance occurred that forced him to leave. At the end of six months the youths were given the opportunity to reenlist for another six months. Those who declined were given physicals and provided with transportation to their homes or places of enlistment, depending on which was nearest. [28] TRAINING AND EDUCATION What to do with the enrollees during their free time provided a challenge for the various administering agencies. Prior to the creation of the ECW, the NPS had provided interpretive and educational talks to the visiting public at parks. In May 1933 NPS Director Albright offered the services of the Park Service to the Army in providing training and lectures on forestry and other topics of interest to the ECW youths. The Forest Service contracted for motion picture projectors to be used by their camps and other agency camps to show films of an educational nature. One projector was to be circulated between every eight to 10 camps. The Park Service obtained forestry training manuals from the Forest Service to distribute to the enrollees. The Park Service also produced a 32-page booklet entitled "The National Parks and Emergency Conservation" to be distributed to the camps. [29] During the first year of the ECW's existence, the enrollees received only minimal training and education. With the continuation of the ECW, Park Service Assistant Director Harold C. Bryant, in cooperation with the Office of Education, began to establish a more formal education program. In December 1933 the president, the ECW director, War Department officials, and the commissioner of education set up a formal education program. The commissioner of education appointed an education director of the ECW who operated out of Fechner's office. His duty was to implement and supervise an educational program throughout the country. An educational advisor was assigned to each of the nine army corps headquarters and to each ECW camp as part of the camp superintendent's staff. [30] The War Department on May 29, 1933, issued a memorandum urging camp officers to set up educational and athletic activities for the camps. The officers, in cooperation with NPS officials, set up as many as 20 evening courses per camp. In natural areas, forestry work was discussed; in historical areas, talks were given on the importance of that park in American history The enrollees expressed appreciation and interest in these programs. As the first period of work drew to a close, Director Cammerer requested that park superintendents and state officials assist the Army in preparing an expanded educational program for the winter months. Director Cammerer urged the organization of study classes, discussion groups, and hobby clubs; professionally guided field excursions to study significant historical, geological, or biological features in the area; lecture programs; visual presentations such as motion pictures or slides; and recommended additional reading material on appropriate subjects to supplement lectures and discussion group activities. Parks were to submit proposals to the director for final approval. As an example, the park naturalist at Acadia National Park recommended a program that would offer lectures once a week on natural history subjects. If enrollees expressed interest, a study group was formed with the park naturalist. [31] On November 2, 1933, Commissioner for the Office of Education George T. Zook presented to Director Fechner an outline for an educational program for ECW camps. When the plan was presented to the ECW advisory council, the Departments of War, Interior, and Agriculture objected to it. Major General Douglas MacArthur argued that the ECW's mission was not education and that the original act and the president's directive did not mention it. General MacArthur eventually agreed that an education program could be carried out but that it had to be placed under the control of the Army. On November 22, the president gave approval to a nationwide educational program placed under the auspices of the nine Army corps commanders. Each corps area was assigned an educational advisor selected by the Office of Education who assisted camp commanders in establishing an educational program. Each camp also had an educational advisor, while an assistant camp leader was chosen from the camp enrollees to help with the program. In 1933 full implementation of the educational program was left to the discretion of the camp commander. The program encouraged continued cooperation between the military and the Park Service and was conducted only at night. Only job-related training was permitted during working hours. [32] In December 1933 Clarence S. Marsh was selected director of ECW education. His first task was to appoint approximately 1,000 educational advisors selected from the ranks of unemployed school teachers. By January 1934 a budget was prepared and submitted, and at the end of March the advisors were working in the camps. Courses taught were designed to assist the men in obtaining jobs after leaving the camps. [33] During the second year school was held each night for half an hour per class, with the men divided according to their previous education. Classes were presented in reading, writing, arithmetic, grammar, spelling, history, civics, and geography, along with a special class for illiterates. On the national level each agency designated a representative to be on the educational advisory committee to give guidance to the program. (The Park Service representative was Dr. Harold C. Bryant.) Each camp employed an educational advisor at a salary of $165 a month, and camp youths selected to assist him were paid $45 a month. The educational advisors soon took over the responsibility for the camp's athletic and social programs. The program operated on limited funds and depended on help from the military and NPS staff. At first, the night classes were well attended, but after a month enrollment dropped dramatically. The superintendent of Morristown National Historical Park commented that his boys were not interested in formal academic classes but were interested in technical classes related to the conservation work. The educational program faced not only the skepticism of park superintendents but the hostility of some camp commanders. [34] In 1935 the ECW education program attracted 53 percent of the enrollees. There was enough antagonism among the educational advisors, the camp commanders, and the project superintendents that the Washington Office of the Park Service directed project superintendents to extend full cooperation to the camps' educational advisors and to notify them formally that the parks' full facilities were available for their use. Camps at Death Valley National Monument offered 56 courses, the majority of which were to be completed by correspondence. The courses varied from the practical to the esoteric. In September 1935 Director Fechner announced that the education program was to be reorganized, with more emphasis on vocational training. [35] A new system of training was adopted in 1936 that encouraged supervisors to instruct the youths to improve the quality of their work and to give training that would aid them in obtaining jobs when they were discharged. To achieve these objectives, the Park Service published a large number of technical leaflets for use in job training sessions with the enrollees. This type of job-related training was the responsibility of the Park Service. [36] Starting in 1937 each camp commander was required to provide for 10 hours a week in educational and vocational training. The Park Service was not comfortable with teaching strictly academic courses and conducted some classes on a more casual basis, geared toward practical application. The Park Service preferred to take the workers out for field trips so that naturalists/rangers could use the parks as vast natural laboratories. In Wyoming the Park Service instituted a program of training designed to help the enrollees obtain jobs with private enterprise after their discharge. The preliminary results of this program were encouraging. On March 19, 1937, the Army, Forest Service, and Park Service again reaffirmed that the technical agencies would be responsible for work-related training, and the Army, with assistance from the two technical agencies, for the education program. By December, however, Morrell of the Forest Service and Wirth of the Park Service proposed to the CCC advisory council that the entire educational program be revamped. They suggested that the educational courses and educational advisors be removed from the camps and replaced by an on-the-job training program under the control of the technical agencies, or at least have the entire educational budget transferred from the Army to the technical agencies. Neither suggestion was acted upon. [37]

PROBLEMS AND CHALLENGES Today the CCC is fondly remembered as one of the most successful New Deal programs, but when it was authorized in 1933, it faced a number of challenges. Desertions From the outset, desertions, resignations, and expulsions took a toll. By late June 1933 Skyland camp in the proposed Shenandoah National Park had only 176 of the original 200 youths, and enrollees were deserting on a daily basis. Youths in a camp in Mount Olympus National Monument were proud of their low desertion rate and placed the sign " We Can Take It" over the camp entrance. By early August 1933, 10,000 additional men were needed to replace those who had left the ECW. During the next several years the desertion rate remained low but steadily increased. Despite actions to boost morale, desertions were at 18.8 percent in 1937, and in the next two years one out of every five enrollees was dishonorably discharged. In 1939 the desertion rate for the CCC was nearly 20 percent--compared to 8 percent in 1933. The next year the desertion rate remained at a high level and recruitment quotas were not met. At Glacier National Park and other areas, this resulted in authorized camps not being established. [38] Enrollee Behavior and Public Reactions In May 1933 the youths began arriving in the various camps, creating local community reactions ranging from joyous welcome to fear and deep concern over the presence of persons often described as "bums." [39] In some areas, townspeople objected to the establishment of camps because they feared that the youths were vagrants and toughs and that they would rob their homes and violate their daughters and wives. The residents of Bar Harbor, Maine, were particularly distressed about the location of an ECW camp at nearby Acadia National Park and wrote letters to the president opposing its establishment. But President Roosevelt believed the ECW recruits to be hard-working youths down on their luck and permitted the camp to be constructed . Roosevelt's faith in the enrollees proved correct, as neither crime nor the rate of illegitimacy increased. In the proposed Shenandoah National Park, the locals initially fired guns into ECW camps and set forest fires; after six months, as they realized that the ECW was an economic benefit to the community, their hostility gradually subsided. [40] Youths from the urban centers of New York, New Jersey, and Chicago were frequently dispatched to camps as far away as Rainier, Olympic, and Glacier national parks. Roger W. Toll, superintendent of Yellowstone National Park, had a problem with such recruits. The boys had been sent from the poorer areas of New York City and were resentful of having been placed in Wyoming. They were rude to park visitors and by the middle of June they were homesick and in a mutinous state. A confrontation arose when rangers and men armed with pick handles were sent into the camps to keep order. The mutineers backed down, and nine of the ringleaders were discharged and sent back to New York. In 1934 Superintendent Toll requested that recruits for Yellowstone be more carefully selected to avoid repetition of these events. [41] The speed at which the original camps were established led to a number of problems. During the first weeks of ECW operations, enrollees were sent to work with no supervision and no work assignments and stood idle until transported back to camp. At other times, camp commanders kept an inordinate number of recruits around the camp to perform housekeeping tasks instead of sending them on work details. In some areas, complaints were received that the ECW recruits were violating game laws and killing the park's wildlife. People in Vicksburg, Mississippi, believed that the ECW workers at Vicksburg National Military Park were destroying historical sites, while camps in Morristown National Historical Park, Acadia National Park, Shenandoah National Park, and Yellowstone National Park were unable to adequately perform work assignments until July, 1933, because of a lack of recruits. But these early problems were soon resolved. [42] Another charge leveled at the ECW program in the Park Service was that appointments to nontechnical positions and some promotions were based on political affiliation rather than on merit. The official policy was not to give job applicants more consideration because of their personal political affiliations, but this policy was not always adhered to in some places, such as Acadia National Park and Shenandoah National Park. In both parks individuals apparently gained employment because of their Democratic party affiliation, although such incidents remained isolated. Charges of political manipulation were made at various times during the existence of the program. These abuses do not appear to have been widespread, however. [43] In the second year of the ECW program, people were still fearful that a camp near their town would be harmful. The citizens of Luray, Virginia, expressed deep concern when it was announced that a Park Service camp was to be located in Thornton Gap. They argued that the camp location would pollute the local drinking water and that the enrollees would be a "social menace" to the community. But this did not deter the Park Service from locating a camp in the vicinity. [44] In 1933 and 1934 the Park Service opened the camps to public inspection and encouraged visitors to look them over. To gain further community support, district officials, camp inspectors, camp officials, and park officials were encouraged to speak and show films before the Chambers of Commerce, as well as the Rotary, Kiwanis, and other civic organizations. These talks were to emphasize the beneficial aspects of the ECW to the parks and local community. [45] During 1934 new problems arose as "confidence men" used the ECW for their own purposes. For example, in Jersey City, New Jersey, a man using the name of Sergeant Major Barnes claimed to represent the Park Service and collected money from families of ECW workers on the pretense that their son or relative was failing in health. He promised to use the money to ship the boy home with an honorable discharge, a pocketful of money, and a job. None of this was true, and Major Barnes disappeared after receiving the money. Park Service authorities alerted the public when these frauds became known. [46] In November 1934, 250 ECW workers rebelled while being moved from Maine to camps in Maryland and Virginia. The enrollees were under the impression that they would not be transferred from Maine. While en route they beat their officers, locked them in a baggage car, and took over the train. The transfer proceeded without further incident after 150 policemen appeared on the scene. Objections to being transferred from summer to winter camps were rare. [47] When the hearings were held on the 1933 Federal Emergency Relief Act, fears were voiced by William Green, president of the American Federation of Labor, and others that any civilian conservation corps would spread militarism and fascism throughout the country and reduce the wages of forest workers. These charges particularly disturbed government officials who administered the program. Assistant Director Wirth became concerned when he found ECW youths on duty at the entrance stations of the Skyline Drive clicking their heels, standing at attention, and saluting when cars passed. ECW camp officials were instructed that the youths were to be courteous, but were not to maintain a military deportment. The Park Service also scheduled work projects that did not compete with jobs being done by local woodsmen. [48] During the next several years, problems arose over the abuse of alcoholic beverages in camps, vandalism to national parks and monuments by enrollees, mismanagement of program funding, and general unrest in the camps. The most serious incident occurred when five CCC camps in Shenandoah National Park revolted in November 1937. More than 100 enrollees in these camps refused to work and were dismissed. The incident received widespread publicity in the Washington papers and Director Fechner ordered an inquiry. The investigation revealed many causes for the unrest. Southern and northern enrollees with completely different backgrounds and outlooks clashed repeatedly. A number of the recruits from urban centers had difficulty adapting to the rural environment. Other enrollees were sons of coal miners and viewed striking as a natural way of achieving redress of grievances. These factors coalesced in mutiny. Yet this was an isolated incident, and the vast majority of CCC camps in NPS areas solved problems in less dramatic fashion. [49] Black Enrollment Another problem area was the treatment of racial minorities. In the early depression years jobs that had traditionally gone to blacks were taken by whites, leaving higher unemployment among black youths. The first ECW bulletins to state selection agents directed that no discrimination because of race, color, or creed would be allowed. Still, within the first few weeks of the ECW, Director Fechner let it be known that black enrollment would compose no more than 10 percent of the total enrollment in the program because blacks constituted roughly that portion of the total U.S. population. [50] When the program began, blacks were mostly placed in segregated camps under the supervision of white officers and foremen. As difficult as it was to place white camps near communities, the problem was greatly magnified when establishing black camps. The solution was to locate black camps on federally owned land far away from hostile population centers. This policy resulted in a proportionately larger number of black camps being placed in NPS areas. [51] Despite the apprehension of local communities, black camps were established at Gettysburg National Military Park, Colonial National Monument, Shiloh National Military Park, Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, Shenandoah National Park, and other NPS areas. Over the years, the superintendents of these parks expressed pleasure with the work accomplished by the black enrollees, and the hostility in the local communities gradually subsided. [52] By 1935 the Park Service was being asked by black organizations to select blacks for project supervisor and foreman positions. Director Fechner introduced this matter in an ECW advisory council meeting, but representatives of the Army and the Park Service urged him to continue his policy of segregation. They further suggested that blacks should always be under white supervision. Fechner had found that in some areas under NPS supervision, communities were promised that only white camps would be assigned there. He directed the Park Service to correct this misconception immediately and to notify such communities that they were to accept whatever company was assigned. Fechner later ruled that blacks were to be enrolled only to replace blacks that had left the ECW. In 1935 President Roosevelt issued an executive order instructing that blacks be given official positions in the ECW. [53] The War Department and the Park Service moved slowly to implement the president's directive in forming an all-black company (including officers and supervisors). It was decided that the black company in Gettysburg National Military Park be established as a model all-black camp. That camp would then be evaluated to see the feasibility of placing other camps under black supervision. Full conversion from white to black supervisors was completed in 1940 when the last white supervisors at Gettysburg National Military Park were replaced by black foremen. The project superintendent, three graduate engineers designing park CCC projects, the camp commander and his staff all were black. Using black enrollees under black supervision was deemed successful by the park superintendent and the Army. The only other all-black company under the jurisdiction of the Park Service was established in 1937 at Elmira, New York, as part of the state parks program. [54] During 1936 the War Department decided to move black camps from the mountainous areas of Virginia to the Tidewater region. Many of the camps were administered by the Park Service, and the move created a number of problems. Local communities expressed concern about bringing in blacks as did some park superintendents. The superintendent of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania Battlefields Memorial National Military Park complained that continuation of the park's historical education program was impossible using black enrollees because of the hostility of local whites toward blacks. In Mammoth Cave National Park a black camp was scheduled to be relocated from one area of the park to another. Local opposition to this move was so strong that the camp was moved to Ft. Knox, leaving Mammoth Cave National Park with two less camps and unable to accomplish planned work. [55] As the CCC faced reductions in 1937 and 1938, Director Fechner decided to reduce black camps in proportion to white camps and to locate all-black camps on national park and national forest lands. Meanwhile black organizations and newspapers kept pressure on the administration to integrate the camps. Moving black camps into areas formerly occupied by white camps led to protests by white communities in Oklahoma, Maryland, Virginia, Georgia, and North Carolina. Once the black camps were in place, they usually were accepted by the community and carried out the work program admirably. Yet in the South it proved difficult to use blacks in any public contact work, such as guiding tours or fee collection. [56] Pressure by black groups mounted in 1939 to integrate CCC camps. The Park Service attitude toward racial segregation was that state laws and local customs would be followed in the matter of segregation. Thus, the southern camps remained segregated while some of the northern camps were integrated. During the year a racial crisis arose at Sequoia National Park, California, when fights broke out between white and black camps. The park superintendent claimed that mixing whites and blacks on fire lines created situations that could only lead to further racial incidents. He recommended that the black enrollees be transferred to areas where they would not come into contact with white enrollees. Instead Park Service officials kept the black CCC camp in Sequoia, and no further incidents occurred. [57] By 1940, 300,000 black youths and 30,000 black veterans had served in the CCC in 43 states. In the final years of the CCC the number of black camps continued to decrease. The major difficulty continued to be the placement of a black CCC company, particularly when it replaced white companies. [58] As Congress debated the termination of the CCC, the black press rallied behind the program's continuation. The black-oriented newspaper The Pittsburg Courier commented:

|

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

paige/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 29-Feb-2016