|

Padre Island

An Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER TEN:

INTERPRETATION AND COLLECTIONS MANAGEMENT

History of Management

Almost two years passed after Congressional authorization of Padre Island National Seashore in 1962 before the National Park Service made any significant headway toward building an interpretive program in the new park. Although various Park Service biologists and planners visited and reported on the resources of Padre Island from the 1920s through the 1950s, no one completed an in-depth study that might provide enough background material for an interpretive program. Likewise, while a number of local scientists, conservationists, and historians collected information on Padre Island, their work remained in a number of different locations including Corpus Christi State University, Texas College of Arts and Industries in Kingsville, the Welder Wildlife Foundation, and area historical commissions. The work of local Padre Island enthusiasts also came in formats ill-suited for devising an interpretive program ranging from highly technical or academic papers to personal scrapbooks and junior historian projects.

In 1964 Superintendent Bowen took the first step toward developing the interpretive program. Following the trends of the 1960s, Bowen hired a biologist as park naturalist to coordinate resource management and initiate interpretive and collection programs. James K. (Ken) Baker transferred to Padre Island from Carlsbad Caverns National Park. Because he was originally from Corpus Christi, his arrival attracted local newspaper interest mostly as "hometown boy returns," but also as the first public notification of the intention to promote resource conservation and visitor education. Baker immediately focused on two park issues: resource conservation and collection of information for interpretation. In addressing the first, he drafted "Special Regulations" on visitor use and enjoyment, protection of wildlife and natural features, and regulation and removal of oil/gas and other minerals from the park. For the second issue, Baker gathered information about the island and began to collect natural resource material. [1]

Almost one year later, Superintendent Bowen reported on Baker's progress. He stated that an extensive literature search for information was underway and that several publications were already acquired for the growing park library. Bowen also mentioned that Baker had written a charter and bylaws for a Padre Island Natural History Association. The support Association, typical of many national parks, would be incorporated as a nonprofit under Texas law sometime in spring 1966 and sell literature in the park visitor center. In a final note, Bowen stated that the staff had completed the draft of "Special Regulations" and comment was being sought from various State and Federal agencies with an interest in Padre Island. [2]

The staff had begun its most intensive effort for interpretation a few months earlier in 1965. Through a handful of direct contracts, the staff set up special research projects with professionals that focused on subjects needed in an interpretive program. Dr. Theodore N. Campbell of the Department of Archeology at the University of Texas at Austin completed the first of these in early 1965. His archeological appraisal of the island was primarily important for the placement of development and subsequently for interpretation. At the same time, the staff contacted individuals with an interest in the island to conduct a biological survey for both Padre and Mustang Islands. Five individuals from different biological fields agreed to participate: Dr. Henry H. Hildebrand from University of Corpus Christi on marine biology; Dr. Burrus McDaniel from Texas A&I College on birds; Fred Jones on plants, Anne Speers on mollusks, both of the Welder Wildlife Foundation; and the Park Naturalist James K. Baker on terrestrial vertebrates. Park officials expected the survey team to complete all work within two years, including a manuscript suitable for publication. The staff arranged with Dr. W. Armstrong Price for a geological study of Padre Island and the Laguna Madre. The Southwest Parks and Monuments Association first funded the Armstrong work but funds from the Department of Economic Geology at the University of Texas at Austin allowed it to be completed. The only non-scientific work was contracted to the well-known Texas historian Dr. Joe B. Franz at the University of Texas at Austin. Franz agreed to compile a history of Padre Island and conduct a survey of sites and structures of the park. [3]

The newly contracted research covered the typical elements of an interpretive program, but the staff had no overall direction for implementing one. As a beginning, the National Seashore staff prepared a rough draft of an interpretive prospectus and developed some simple panel exhibits for use in the headquarters building. These exhibits complemented the work of the Padre Island Natural History Association, finally incorporated in 1966, which was prepared to publish materials on Padre island and sell these and other items at the headquarters building. As a means of acquiring specimens and artifacts for interpretation, the park staff collected approximately 300 species of plants and animals during 1965. Seashells comprised most of the collection, largely begun with donations from Anne Speers of the Welder Wildlife Foundation. [4]

Over the next two years, National Seashore staff developed the park's interpretive program without an approved Interpretive Prospectus. They conducted research, assembled basic material, and revised the Prospectus in anticipation of assistance from Washington. To process photos and plates for the biological survey manuscript, the staff added a dark room in the headquarters building in 1966. The staff progressed slowly toward a full-fledged interpretive program for the new park. Their work slowed as complications arose with land acquisition and development plans. These problems in turn influenced the number of visitors coming to the National Seashore. After half a year of being open in 1965, park officials reported 46,424 visitors and only 152,432 in 1966. These numbers were behind earlier estimates and gave little impetus for implementing a stronger interpretive program. [5]

In July 1966 James Baker transferred to Joshua Tree National Monument in California. By September, Derek O. Hambly transferred to the National Seashore as the second park naturalist. Hambly, also a biologist, brought eight years of experience with the National Park Service, having served at Colorado National Monument, Great Smoky Mountains, and Lake Mead. He announced soon after arrival that he would focus on interpretive planning in light of the expected visitation increases. [6]

In early 1967, Superintendent Borgman formally requested the Natural Science Division in Washington, D.C., for assistance on an interpretive plan that would at least be an intermediate step. This preliminary interpretation, as Borgman envisioned it, would be set up along the walkways of the new Malaquite facilities which were large enough to carry visitors and interpretive panels at the same time. [7] Borgman's concept unfortunately did not take into account the intense climatic and seashore forces along the beach, especially during the summer months.

By late 1969 when the completed Malaquite Beach facilities opened to visitors, park staff offered a basic interpretive program. Park Naturalist Derek Hambly designed the Grassland Nature Trail near the entrance to the National Seashore. With a mimeographed guide briefly describing the composition and characteristics of the grasslands and its accompanying natural resources, visitors could pick up the trail near a large rectangular sign mounted on posts and follow along a primitive trail that circled through the back dunes of the island. The Grassland Trail became a significant attraction in the National Seashore during the early years of the park and for many provided the only introduction to the sensitive ecology of the barrier island. [8]

Hambly also adapted the upper story of the Malaquite View Tower for an evening program that lasted through the 1970 season. Two seasonal employees, generally local high school students, performed all other interpretation from the Malaquite Beach Pavilion during the summer months, focusing on walks and evening activities. The park naturalist and a park technician conducted other interpretive activities during the course of the year, but during peak visitor periods they maintained the Information Desk at the headquarters building and spent any additional time training seasonal employees. [9] Hambly's newly created Padre Island Natural History Association began to flounder around 1970 as the park entered a transitional period. Despite a merger with the larger Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, park managers decided to drop the Association because of the amount of bookkeeping and record keeping necessary. By 1971 all cooperative associations ceased. [10]

In 1972 Superintendent James McLaughlin, relatively new to the park, redesigned the interpretive program. Following the departure of Park Naturalist Derek Hambly to be the superintendent of Fort Davis National Historical Site, McLaughlin created a new Division of Interpretation by separating the existing Division of Interpretation and Resources Management into two departments. For a short period, Park Technician Barbara Shelton became the new chief of interpretation, but soon resigned to pursue other professional interests. Afterwards, Superintendent McLaughlin upgraded the position to an environmental specialist and promoted Park Ranger Richard McCamant. McCamant largely focused on monitoring oil and gas operations rather than interpretation or scientific research. [11]

Shortly afterwards, Robert Whistler transferred from the National Park Service in Washington, D.C., to serve as the first chief naturalist. Under Whistler's direction, the Division of Interpretation increased visibility and expanded visitor education. New programs such as nature craft classes and "surprise walks" added a special dimension to visitors' experiences at the National Seashore. Whistler also developed informational brochures and handouts and scheduled the first off-season programs for clubs, scouts, and professional organizations. An evening campfire program, common in many national parks, was initiated, but discontinued by Superintendent McLaughlin because of its potential to attract vagrants to the park. Between 1971 and 1972 National Seashore employees recorded a significant increase in attendance at evening programs, craft classes, off-site talks, and environmental school walks. Participation in nature walks, however, dropped. [12]

The National Seashore staff began an aggressive interpretive program in 1973 centered around participatory demonstrations. Sand candle casting, star watching on the beach, coquina clam stew cooking, and art classes were offered on the beach. The Malaquite View Tower was modified for classes that included construction of nature plaques, fish printing, and handicraft projects. When a new visitor information desk also opened in the summer at Malaquite Beach, the staff offered small natural history exhibits, information on interpretive programs, and general National Park Service information. [13] In the following year, despite visitation declines because of the energy crisis, interpretive activities still increased. Evening slide programs, morning beach walks, and afternoon nature films constituted most of the interpretive activities, but arts and crafts projects and beach demonstrations continued. Chief Naturalist Whistler revived the earlier contract with the Southwest Parks and Monuments Association with a new contract signed in 1974. The cooperative agreement with the Association brought a wider array of materials to the information desk and broadened the scope of interpretation at the National Seashore. [14] In 1975 park managers opened a new visitor center desk and interpretive office at the ranger station, allowing a Park Naturalist to be based there full time, and a seasonal interpreter to be stationed at the desk. [15]

The Grasslands Nature Trail continued to be an attraction for the park. With financial assistance from the Southwest Parks and Monuments Association, the staff printed trail guides that were distributed free of charge from 1970 to 1975. During these years, the guide became one of the few publications specifically devoted to interpretation of the island. It was upgraded in 1976 to 16 pages and photographs and sold for a modest 20 cents. Trail hikers left payment in a guide box at the beginning of the trail until petty theft forced an end to the distribution. [16]

In 1972 Chief Naturalist Whistler initiated the Volunteers in the Parks (VIP) program approved by Secretary of the Interior Walter Hickel and Congress in 1969. [17] Beginning with a small program, Whistler arranged for two young volunteers to maintain aquariums at the headquarters and Gulf District Ranger Station during the winter and spring. The volunteers collected specimens in the Laguna Madre through seining and supplied both aquariums. Over the next few years the program expanded. Volunteers served as dispatchers, receptionists, environmental education leaders, interpretive guides, photographers, and researchers on various resource management projects. As the program grew in importance, college students, retirees, citizens working off misdemeanor charges, and physically challenged persons participated in the program. [18] In 1987 Whistler developed a program for winter Texans who stayed in the campgrounds at the National Seashore. These winter Texans catalogued collections and assisted with interpretive activities. By the late 1980s the National Seashore staff expanded the program further by enrolling volunteers associated with the Texas Coastal and Adopt-a-Beach clean up program. This increased the number of enrollees to 816 in 1989 and to date serves as the peak year for participation. [19]

1975 Interpretive Prospectus

The first successful effort to develop a park-wide interpretive program began in 1975. Chief Naturalist Robert Whistler prepared a draft Interpretive Prospectus that was assisted by a National Park Service planning team from Harper's Ferry and the Denver Service Center. The planning team described the existing interpretive program and facilities as "minimal" and "unsatisfactory." They outlined a set of factors limiting interpretation that included heat during the summer, wind off the ocean, sounds or noise from the surf, large mosquito populations behind the foredunes, corrosion from the Padre environment, and high humidity. Two objectives were also identified:

To stress the historical interaction of man and the natural environment of Padre Island. Visitors should begin to consider their own environment and how they relate to it.

To help visitors enjoy the recreational resource of Padre Island National Seashore for the natural area it is, emphasizing activity-oriented exploration that does not seriously impact the resource. [20]

At the north entrance, the Prospectus called for a radio message repeater located near the Gulf Ranger Station that would provide current safety messages about weather, beach conditions, and park regulations. The team suggested retaining the existing Grasslands Nature Trail but with an additional wayside exhibit on dune grasslands. They also proposed a new Fresh Water Pond Trail in the vicinity of the Malaquite Beach development and including a wayside exhibit on plant and animal life at the beginning of the trail to be accessed along a raised, wooden, covered walkway. [21]

The planners further recommended developing historical interpretation at the Novillo line camp, just south of the entrance to the National Seashore. The line camp could be the focus of three different interpretive themes: cattle ranching on Padre Island, different land uses by man and their impacts on the environment, and the role of recreation as the basis for National Park Service administration of the National Seashore. Interpretive development was to be simple, consisting of a small parking area, short trail, and several wayside exhibits covering the three themes. The Prospectus mentioned the problem presented by the visual and noise distractions from the adjacent Chevron Oil Company separation plant. [22]

On the Laguna Madre side of the National Seashore, the planners envisioned a shaded exhibit near a proposed pier and launch ramp. This planned exhibit would describe recreational opportunities of the spoil banks and how to safely enjoy them. The story of the spoil banks as bird sanctuaries, protective programs, and needs for the sanctuaries could be another interpretive idea. Another exhibit on the dunes could also be placed on the Laguna Madre to provide information on the fragile nature of dunes and encourage visitors to avoid walking or driving on them. [23]

At the Malaquite Beach complex, the Prospectus mentioned building a "modest" interpretive facility connected to the other development by a concrete walkway. The proposed facility included a visitor center, exhibit space, naturalist and environmental education center, and a ranger's district office. Appropriate exhibits at the facility included historical subjects such as the Karankawa Indians, Spanish exploration, and the American years of cattle ranching, oil and gas exploration, and military use. The planner added an outdoor exhibit complex near the beach, reached via the visitor center, to highlight dune ecology and the dynamics of the Gulf of Mexico and Padre Island. [24] Additional dune ecology would be addressed at Yarborough Pass where a proposal in the 1974 Master Plan called for a shell road to end. Extensive facilities were planned for the site that included interpretation of the environment. [25]

The interpretive planners developed other activities that they detailed in the Prospectus. They envisioned a view tower, placed high enough to avoid mosquitoes, that allowed a view of the Laguna Madre and intracoastal shipping activities, and considered wayside exhibits to educate the public on the varieties of birds at the National Seashore. The planners suggested additional informal and participatory programs including guided beach walks, sketching walks, beach combing, surfing, and surf fishing. They even suggested a bicycle trail to parallel the main road and from the campground at Malaquite Beach connect to another one at Yarborough Pass. For automobile travelers, special "pull-offs" for photographs or observing the ponds were recommended along the existing roadways. [26]

In the final statements of the Interpretive Prospectus, the planners suggested new and better publications, including a park handbook, to describe the environment of Padre Island. Also, they conceived of a series of monographs on technical subjects such as topographic maps and navigational charts. The planners recommended that the National Seashore maintain a minimal collection keeping only those items that primarily supported the interpretive program. As an exception to the minimal collection idea, the planners recommended that the National Seashore acquire the artifacts recovered during an archeological salvage program on Padre Island. [27] The final placement of these artifacts -- owned by the State -- was a topic of intense debate during the late 1960s and would eventually be placed in the Corpus Christi Museum following a court order in the 1970s.

The planners for the 1975 Prospectus emphasized wayside exhibits throughout the National Seashore as the primary means of interpretation. They also used development proposals highlighted in the 1974 Master Plan as the focus for interpretation. By the early 1980s park officials were beginning to question the location and scale of much of the proposed visitor facilities and instead favor resource conservation over visitor accommodation. In time, the 1975 Prospectus became obsolete as a guide. These projections seldom mentioned cost estimates, budget constraints, or visitation expectations and thus remained largely conceptual. Almost 15 years later in 1989, a new Interpretive Prospectus scaled back the earlier concepts and shifted the emphasis of interpretation.

1989 Interpretive Prospectus

In the mid-1980s Chief Naturalist Whistler coordinated a new planning team to update the 1975 Interpretive Prospectus. The new planning team, consisting of National Seashore staff and Harper's Ferry professionals, was guided by the 1983 General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan and a new program devised by John Cook, regional director of Southwest Regional Office, that designated Padre Island National Seashore as bilingual (Spanish/English) for interpretive media. In the opening lines of the 1989 Interpretive Prospectus, the planners still described the interpretive facilities and programs as "minimal." As they went on to describe other existing conditions in the park, the overall setting for interpretation seemed difficult. The absence of a visitor center in the new Malaquite Beach complex, inadequate staffing for the visitor center, inadequate outreach programs, and limited use of wayside exhibits headed the planners' list of constraints. The planners further noted that existing interpretive programs reached only 10 percent of visitors. This problem, they noted, resulted from changes in visitor use patterns over the years of park operation and the attraction of different sets or types of visitors depending on the time of year and section of the park. As a last issue, the planners stated that except for a Spanish version of the park's welcome brochure, all interpretive media were in English. [28]

The interpretive planners took several new approaches in the draft Prospectus in deference to the shift to resource conservation. They recommended a revision of earlier statements on interpretation that included five new themes:

Barrier Island Processes/Function -- Discussion of wind and wave energy as a part of the dynamic equilibrium on a barrier island.

Barrier Island Ecology -- Coverage of the biological and mineral resources of the island that represent integrated systems.

Edge of the Sea -- Marine processes of the near-shore sea and the protected lagoon. Representative plant and animal species and their natural history.

Seashore Recreation/Visitor Awareness -- Examples of how visitors can enjoy the seashore without degrading the environment.

History - The effects of human occupation on Padre Island. [29]

The planners identified two park facilities for exhibits: park headquarters in Flour Bluff and the Malaquite Beach Visitor Center. The 1989 Prospectus suggested that new static exhibits, a short audiovisual program, and more outdoor signage for tourists should be added at the headquarters. At the Malaquite Beach Visitor Center, planners suggested exhibits on the functions of barrier islands and human use and association with the barrier island. Additional subject areas included in the report were safety topics such as riptides, sun, wind, sting rays, sharks, jelly fish, trash (toxic wastes), and emergency phone numbers. Most of the exhibits were static, but the planners also envisioned an audiovisual program on the natural and human history of Padre Island for the Visitor's Center. All exhibits were to be bilingual. [30]

Several other areas mentioned in the Prospectus departed from the 1975 version. The new plan called for a long-term solution to the environmental education facility to be a barge moored on Bird Island Basin. It focused on the Laguna Madre ecosystem and offered bilingual interpretation, incorporating both pontoon boats and a glass bottom boat. A new shift on interpreting the Novillo line camp also appeared. Although occasional recreations of cattle drives were already being staged successfully, the park's overall management strategy pointed to benign neglect. The planners suggested, however, one wayside exhibit on cattle grazing. Finally, existing wayside exhibits, mostly ineffective because of exposure to the extreme heat and elements, were eliminated. [31]

The planners also introduced new programs including self-guided trails, especially a cross-island nature trail. Other ideas were to add bicycling and jogging trails, a freshwater pond trail, a boardwalk trail along South Beach, and relocating the Grasslands Nature Trail. Park interpreters called for expanded auto audio taped tours, outreach programs, and environmental education programs to complete the park's interpretation. In conclusion, the Prospectus encouraged additional oral history work, funding needs, and new interpretive programming focusing on accessibility. [32]

Unlike the 1975 plan, the 1989 Prospectus focused on quality interpretation of identified themes in a few sites rather than large-scale development around the park. In setting this new direction, Padre Island reflects a maturity in its management toward environmental sensitivity.

Environmental Education Program

During the late 1960s the national environmental movement emerged, that affected the management and interpretation of the national parks. National Park Service personnel created an environmental education program to be implemented in all parks. In 1969 Derek Hambly introduced the first environmental education program at Padre Island by outlining three Environmental Study Areas (ESAs): outer beach, grasslands, and dune-mudflats(s). The outer beach concentrated on three elements: tidal zone, wide beach, and outer dunes. The Grasslands Nature Trail covered the latter two ESAs. [33]

In 1972 Chief Naturalist Whistler revived the ESA program by coordinating with the Corpus Christi Independent School District. The National Seashore staff agreed to lead students on walks of the Environmental Study Areas during the early spring months when visitation was typically low. Staff conducted 22 walks with more than 1,000 children in the first year. The staff discontinued the three ESAs developed by Park Naturalist Derek Hambly in the late 1960s, replacing them with two new National Environmental Study Areas (NESA). A second program also begun in 1972 worked with educators. Seventy local elementary and secondary school teachers attended two Environmental Education Teacher Workshops and 24 participated in a workshop at the National Seashore. The park staff continued its outreach during Environmental Education Week, September 18-23, 1972. Whistler and staff again contacted area schools encouraging them to send students for morning interpretive walks and afternoon slide programs. In total 13 programs with more than 1,000 students highlighted the week. [34]

In 1973 Padre Island staff established a cooperative effort with the Welder Wildlife Refuge at Sinton, the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, and the Corpus Christi Museum. This cooperative provided a uniform format for the Corpus Christi Independent School District to arrange field trips to each location after an orientation on all of them at the Corpus Christi Museum. [35] Although the proposed program was ambitious, a decline in participation occurred in 1974 because of the energy crisis. In 1975, however, the Padre Island staff reorganized, giving an emphasis to environmental education outside the immediate region. After attending a workshop at the National Seashore in spring 1975, a group of high school students from San Antonio developed a series of workshops on environmental issues in their own parks. The San Antonio program developed rapidly and included both indoor and outdoor workshops, the latter conducted in city parks. Padre Island officials reported in the 1975 Annual Report the success of the workshops and that the participants continued to conduct workshops on their own initiative. [36]

The staff's efforts to broaden environmental education proved fruitful. The volunteers organizing the program expanded the workshops to include elementary schools, Cub Scouts and Brownies, and additional high school classes. On the park's side, the chief naturalist scheduled films, sent materials requested, and provided supplies for the workshops. In 1976 the volunteers and staff added special certificates for those completing the workshops. [37]

The National Seashore's environmental program received increasing attention. In 1976 the Washington office of the National Park Service recognized the Grasslands Nature Trail as a National Environmental Study Area. During the 1980s the environmental program stabilized. In 1985 Richard Harris developed a second ESA for Bird Island Basin. He wrote and illustrated a teacher's guide, published by Texas Agricultural & Mechanical University Sea Grant Program. Marie Gillett, a local volunteer, followed in 1987 with a draft ESA on beach trash that was never finished or printed. [38]

Collections Management

In the 1960s, the National Seashore staff made only minimal progress in developing and cataloguing the park's collections. Few of the superintendents mentioned the status of park collections in annual reports or overviews of the park. In spite of the lack of attention, residents from the area often approached Padre Island staff to offer artifacts or specimens gathered on the island. Anne Speers of the Welder Wildlife Institute offered the park her collection of shells; Lou Rawalt, a longtime Padre Island beachcomber, promised to give his lifetime collection of miscellaneous beach items to the park. Park employees also contributed to an unwieldy collection. Park naturalists collected numerous biological specimens and various park rangers picked up items washed up on the beach. All of these became part of the permanent collection. [39]

In 1972 the new Chief Naturalist Robert Whistler mentioned that upon arrival at the park the collections were unsupervised with some of the finest shell specimens missing. [40] Improvement of the collections management became a high priority for Whistler. By 1975 when the National Seashore released its first "Area Collection Statement," the staff reported a significant improvement. Volunteers and staff had accessioned and catalogued all items through the park's accession book and catalogue records. Staff stored museum pieces in standard museum storage cabinets in a locked room that was temperature controlled. Very valuable items, such as Spanish coins or unusual shells, were locked in a vault. As of May 1975, the collection consisted of 28 history items, 17 mammals, 17 arthropods, 51 reptiles, 288 plants, and 368 archeological items. In the same year, National Seashore officials initiated discussions for the National Seashore to acquire Spanish artifacts from recovered shipwrecks off Padre Island from the State of Texas and Texas Antiquities Committee in Austin. Although a permanent placement was not agreed on until later, the Park Service staff used some of the recovered artifacts for interpretive displays and others pieces were lent to area museums. [41]

Ten years after the first collections report, park staff updated the report. Once again, interpretation of the National Seashore became the primary objective for maintaining a collection, and teaching and reference were the primary functions. The 1985 report listed a number of management actions for the collection to support the interpretation program. The staff's primary objective became retrieving three collections owned by the National Seashore but stored outside the park. One of these collections included an insect exhibit held at Texas A&I in Kingsville, but considered so poorly documented that it was not worth including within the park. Corpus Christi State University and Corpus Christi Museum held two other unspecified collections. [42]

|

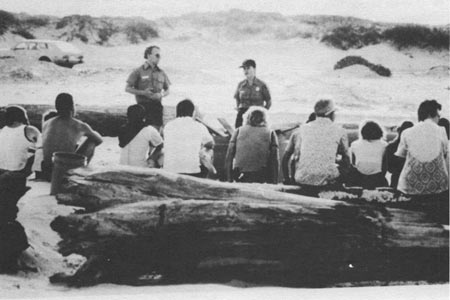

| Figure 30. Ranger Program. Photo courtesy PAIS Archives [531]. |

By the mid 1980s park staff mentioned several other achievements with the collections. The majority of the collection, more than 2,349 objects, was placed in the computer program, with an additional 700 remaining. The park ranger in the Division of Interpretation responsible for the collections devoted 10 to 15 percent of his time to curatorial work. He also trained in the National Park Service cataloging course and planned to be involved in a curatorial methods course of the Park Service. The new Malaquite Beach complex scheduled for development promised to offer three times the exhibit space available in the old pavilion. This was seen as an opportunity to display more of the collection. [43]

The report also listed some problems in managing the collection. A theft of two silver Spanish coins occurred in the early 1980s from a display at the National Seashore headquarters. Another misplaced item was de-accessioned, then recovered. A donated ranch wagon used by Patrick Dunn in his cattle operation on Padre Island and a reproduction Spanish ship anchor were stored in an uncontrolled environment behind the headquarters. Both objects needed proper storage space. Finally, the report stated that the collection of Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site was being stored as part of the National Seashore collection. Six accessions and 135 cataloged items comprised the battlefield collection. Park personnel expected the storage arrangement to continue until the battlefield developed its own facilities. [44]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

pais/adhi/chap10.htm

Last Updated: 14-Jun-2005