|

Padre Island

An Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER NINE:

CULTURAL RESOURCE ISSUES

Local avocational historians researched Padre Island many years before its consideration for a national park. Professional historians also researched the island's history, as in the case of two master theses by Pauline Reese in 1938 and Robert Meixner in 1948. The island's cultural resources, however, were largely unknown until the establishment of the National Seashore in 1962. The originating legislation for Padre Island National Seashore recognized its natural resources and recreational value. Cultural resources seemed of little consequence at the time. After the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966, the Park Service shifted some attention to cultural resources within park boundaries and made at least nominal steps to recognize these as part of the park's interpretation.

In 1964-65 the Park Service initiated the first historical research on Padre Island. Dr. Joe B. Franz of the University of Texas at Austin contracted to prepare a history of the island and a survey of its historic structures. The whereabouts of this work is unknown. [1] Several years later, Park Service historian James W. Sheire of the Eastern Service Center produced an Historic Resource Study that provided a comprehensive overview of the island's history. Sheire developed a thorough bibliography of previous research and outlined various aspects of history that might be adapted in an interpretive program. [2]

Surface Archeological Investigations

In 1963, one year prior to the historical research, the National Seashore staff commissioned its first archeological investigation in anticipation of road and facility construction. Dr. T.N. Campbell of the Department of Archeology at the University of Texas at Austin completed his work by February 1964. Between 1947 and 1956, Dr. Campbell had investigated sites around Corpus Christi Bay and South Texas, eventually publishing several articles on his research. By the early 1960s he was clearly the best informed Texas archeologist on the Padre Island prehistoric cultures. Campbell examined fifteen sites during his investigation, and two years later Dr. Dee Ann Story of the University of Texas at Austin investigated another. [3] Although the study indicated the presence of a number of sites, Campbell recommended that no systematic salvage be done prior to construction. Campbell recommended future multi-disciplinary work that considered the island sites as part of the larger prehistory of South Texas. [4]

Almost ten years later, in June 1973, the National Seashore again contracted for an archeological assessment on sites found within the park boundaries. The Park Service contracted with Dan Scurlock of the Texas Historical Commission for four phases, (1) compilation of data from all previous work, (2) completion of a field reconnaissance to gather additional data, (3) analysis of all data collected, and (4) preparation of a final report. [5] One year later the contractors issued their report. In addition to the 15 sites located by Campbell and one by Story, the new team located 13 new sites. Louis Rawalt, local amateur archeologist and Padre Island homesteader, led the team to ten of the sites. The Scurlock team added the three remaining historic line camps of Black Hill, Green Hill, and Novillo. Of these 29 sites, 20 were identified within the boundaries of the National Seashore. [6]

The 1970s archeological team also surveyed three tracts of park property that were proposed for development. In February 1974 the team examined the area immediately west of the Malaquite Beach pavilion where a sewer lagoon was proposed. During the following month, the team traveled to the southern boundary to survey a six-acre and 12-acre tract in Willacy County. They uncovered no cultural material. [7]

Scurlock's report concluded with a handful of recommendations centered on developing a comprehensive archeological program. First, he encouraged the National Park Service to acquire and study the Louis Rawalt collection gathered from over 30 sites on the island. Scurlock also encouraged study of the collections of W.S. Fitzpatrick of Corpus Christi and A.E. Anderson of Austin. For underwater sites, the team recommended a full-scale magnetometer survey of the surf zone along the Gulf of Mexico. Scurlock elaborated on the comprehensive archeological program that included a permanent headquarters in Corpus Christi and field office on the island. In conclusion, the team sought a synthesis of the widespread cultural and environmental information that could be used for an in-depth interpretation program on the prehistory and history of the island. The total comprehensive archeological program for four years exceeded $700,000. [8]

Underwater Archeological Investigations

The National Park Service believed that significant artifacts existed underwater. Beachcombers and treasure hunters had collected Spanish coins and ship fragments from the beaches of Padre Island throughout the twentieth century. Although most of the finds amounted to very little, visitors learned of the three shipwrecks from the ill-fated 1554 Spanish voyage and searched for its bounty. In 1964, within a few years of the establishment of the National Seashore, Vida Lee Connor discovered the location of one of the shipwrecks during a summer scuba diving adventure off the island. For two years she conducted research on the Spanish shipwrecks and privately documented her discovery. In 1966 Connor announced her find and marked the exact location with buoys. She returned later to observe a diving party excavating the shipwreck. [9] Ms. Connor's discovery unlocked the long-held mystery of the location of the three shipwrecks and created one of the longest controversies over antiquities ever experienced in the State of Texas.

The first of the three shipwrecks, the Santa Maria de Yciar, lay approximately 42 miles north of the mouth of the Rio Grande. During dredging of the Mansfield Channel in the late 1950s, workers destroyed the site leaving virtually no remains of the wreck. Two artifacts appeared, a two-real coin found on the beach and an anchor left on the jetty. The National Park Service later recovered the anchor and made it part of its collection. A second wreck, the Espiritu Santo (41WY3), lay roughly three miles north of the Mansfield Channel; and a third, the San Esteban (41 KN 10), another two-and-one-half miles north of the Espiritu Santo. [10] All three shipwrecks rested in the tidelands on the edge of the National Seashore.

In the fall of 1967, Platoro, Ltd., of Gary, Indiana, began excavation of the middle shipwreck, Espiritu Santo. The company salvaged some 500 items including gold bars, gold jewelry, and early navigational equipment. When General Land Commissioner Jerry Sadler heard of the excavation he protested that the recovered items belonged to the State of Texas. Over the next few years, Platoro and the State of Texas argued in court over rightful ownership. At the same time, the Texas Legislature, largely at the direction of State Representative Cissy Farenthold of Corpus Christi, debated and passed the Antiquities Code of Texas in 1969 to protect future archeological work. The recovered artifacts were moved to the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory of the University of Texas at Austin for analysis and eventually placed with the Corpus Christi Museum for interpretation and display. [11]

After passing the Antiquities Code, the State Legislature set up an Antiquities Committee to oversee and review proposed excavations on public lands. In 1970 staff of the Underwater Archeological Research Section of the Committee arranged for Underwater Research of Dallas to conduct a one-month magnetometer survey of some twenty miles of the coastline. The survey team uncovered the northernmost shipwreck and confirmed its presence. In 1972 the Antiquities Committee staff arranged for summer excavations of the San Esteban. Brief excavations also followed in 1973 and 1975. The Antiquities Committee staff forwarded all artifacts to the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory at the University of Texas at Austin. [12] All three archeological sites were listed in the National Register of Historic Places on January 21, 1974, as the "Mansfield Cut Underwater Archeological District." [13]

Novillo Line Camp

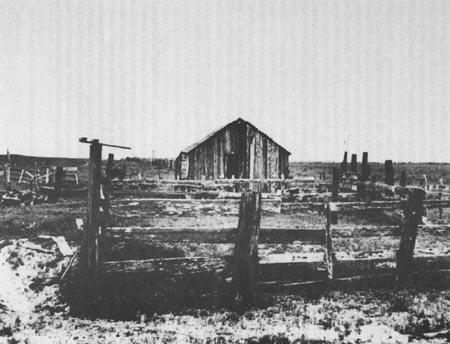

The Novillo Line Camp is the last historic resource within the National Seashore that reflects human use and occupation of Padre Island. Located a few miles within the northern boundary and entrance, the camp was the northernmost line camp used by the Dunn cattle ranch in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It is also largely intact with a collection of small buildings, a pump well, wind mill with concrete water holder, and barbed wire and board corrals. [14]

In the early days of the National Seashore, the park staff gave no special attention to the line camp or its value to the park. Because it sat behind a Chevron Cracking Plant, the camp remained largely hidden from the public who traveled the main road to the Malaquite complex. In 1972 Chief Naturalist Robert Whistler inspected the site and envisioned an interpretive program involving "living history." At almost the same time, Chief Ranger Jim Arnott submitted a nomination to the National Register of Historic Places; it was listed on October 1, 1974. [15] Shortly afterwards, the park staff completed a thorough inspection of the site and developed work programs for its preservation. [16]

|

| Figure 29. Patrick Dunn's Novillo Line Camp. Photo courtesy PAIS Archives [P1124]. |

Whistler took a step toward implementing the living history concept during the Bicentennial celebration of 1976. He invited and contracted with the last foreman for the Dunn Ranch, Jim Lynch, and original vaqueros for a site demonstration. [17] The events included horse shodding and grooming, hand working leather articles, and a general demonstration of how cattle were handled by the Dunn Ranch. Designated camp cooks even prepared food for visitors while the staff and Volunteers in the Park assistants conducted tours. Jim Lynch later offered the National Seashore the last cattle wagon from Dunn's ranch, now in the park's collection. [18]

Chief Naturalist Whistler continued to be concerned about the line camp, especially its preservation and interpretation. In summer 1978, he persuaded the maintenance crew to repair and replace some of the deteriorated boards and apply a wood preservative. Other than these isolated repairs, the park largely ignored the camp, giving priority to other resources. The camp became another concern the following year. Although one of the park rangers was aware of the situation, he allowed a vagrant to occupy the old foreman's cabin in the camp complex. Unfortunately, the vagrant's carelessness with a fire caused considerable damage to the cabin and adjoining buildings. [19]

In 1979 the Southwest Region sent its historical architect to inspect the line camp and report on its physical condition and value as a cultural resource. The architect's report, issued in October 1979, explored four interpretive and preservation alternatives. First, the line camp could be interpreted in a "ruinous condition" and under no major preservation program. Second, Park staff could provide an explanatory panel at one location allowing a view of all structural components. Under this proposal parking for roughly six automobiles could be accommodated off the shell-based road to the Chevron Cracking Plant. The architect outlined a third alternative that included some minimal preservation efforts such as grounds maintenance and removing unnecessary items. As a final alternative, he suggested placing the property under Category D of the List of Classified Structures (LCS) and following a path of benign neglect. [20] The architect concluded that the complex was always temporary requiring some annual maintenance. He added that the buildings and corrals were not "well-crafted" in design or construction. At last, he concluded that the fourth alternative, that of benign neglect, should be the route pursued. [21]

The National Park Service and the Texas Historical Commission entered into a Memorandum of Agreement that adopted the fourth alternative of the architect. Through the 1980s and early 1990s, the Novillo Line Camp remained vulnerable to the island's harsh climate and periodic storms. In 1984, the Chevron Company removed the Cracking Plant that has obscured the camp from public view. It is now visible but not accessible to visitors. [22]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

pais/adhi/chap9.htm

Last Updated: 14-Jun-2005