|

Padre Island

An Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER TWO:

EARLY HISTORY AND USE OF PADRE ISLAND

Historical Accounts of Padre Island

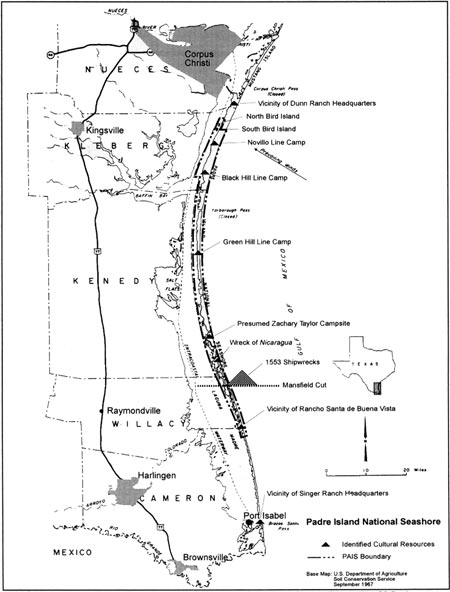

Padre Island boasts a long history of human contact and occupation, yet few traces of these activities permanently marked the island. Likewise, few written documents remain to reveal the early development and use of Padre Island. This is especially true of the period immediately before Europeans arrived more than four centuries ago. Some of the earliest accounts of Padre come from Spanish naval expeditions in the 1680s, conducted only to locate a rumored French colony along the coastline. These sailors reported the existence of fore-island and middle dunes and interior grasslands lacking in trees, but otherwise left technical maritime references with scant details. [1] Ortiz Parilla reported almost a century later an island of "red grass" and "three-spined stickleback," sand dunes on the eastern side, a few freshwater ponds, two small groves of "laurel" and "elder," and a beach strewn with driftwood, damaged canoes, and old ship riggings. [2]

In 1828 Don Domingo de la Fuente, surveyor for the Balli family, traveled the length of Padre Island beginning on the southern end. The survey team reported ranch livestock, bays, sand dunes, and a few "pastures" between the Brazos Santiago Pass and the Balli ranch. As the party moved north, they found a handful of freshwater ponds, and in the extreme north, "high banks" covered with grass, plains, sand dunes with grass, anise herb, and groves of willows, laurels, and oaks. [3]

During a visit to Padre in November 1891, William Lloyd traveled the length of the island. His most interesting observation was a grove of oaks on the west side extending for almost seven miles south from the north end. Some of these grew only six to 18 inches high while others reached eight feet. Whooping cranes, wood ibis, and sandhill cranes wintered here feeding on the fallen acorns. He also noted ducks in the Laguna Madre. Although not seen by him, Lloyd mentioned that others on Padre Island saw deer and coyotes swimming across the Laguna Madre. [4]

These brief descriptions suggest a changing landscape. Although difficult to conclude, reports from unnamed sources at the turn of the century point to a decline in vegetation. This probably occurred after a severe drought lasting from 1896 to 1903 plagued the island. Hurricanes in 1919 and 1933 also contributed to the reduction in island vegetation. Most historians, however, believe that sheep and cattle grazing over a long period of time led to the devegetation. [5]

Padre Island underwent significant shifts over the first few centuries of habitation. The absence of valuable natural resources, or at least "valuable" to them, probably deterred European efforts to exploit Padre Island. With the exception of cattle raising, few considered Padre of value given the abundance of land on the mainland and the more promising economic returns seen there. These beliefs did not preclude use by the two Native American tribes associated with Padre Island.

Native American Inhabitants

The Coahuiltecans, who take their name from the region of northern Mexico and South Texas, made good use of the island, at least by the mid-eighteenth century. While initially remaining south of Corpus Christi Bay, they covered a large area of South Texas, moving campsites according to the availability of food and harvest. Their nomadic behavior tended to be more sedentary than many tribes because they returned to the same campsites year after year. [6]

Medium height and solidly built, the Coahuiltecans foraged the land seeking edible roots and prickly pear cactus tunas. They captured small animals and gathered spiders, worm pupae, fish, lizards, salamanders, snakes, and deer dung. As a supplement to this thrifty diet, the Coahuiltecans collected the beans of the Texas mountain laurel and then made a drink called "mescal". Their villages reportedly consisted of clustered bell-shaped huts formed by arched reeds and covered with animal hides like mats. Although located near fresh water sources and arranged in a neat semicircle, refuse filled the campsites and some observers described them as "filthy". [7]

Of the four smaller tribes comprising the Coahuiltecans, the Malaquitas are associated most often with Padre Island. This tribe records its beginnings in Nuevo Leon, Mexico. First called "Malahueco," the name Malaquitas apparently is a later name documented to 1756 as a description for Indians living near Mier, Mexico. In 1766 Ortiz Parrilla recorded the Malaquitas on Isla Blanca or Isla San Carlos de los Malaquitas, the name for Padre Island, in the area now covered by Kleberg County and northeastern Kenedy County. By 1780 the tribe is documented on the coastal islands near Copano Bay. [8] This tribe provided the inspiration for second Superintendent Ernest Borgman of Padre Island National Seashore to name the Malaquite Beach in 1968. [9]

More historical attention is generally devoted to the second Indian tribe, the Karankawa. These natives covered almost the full Texas coastline extending from Galveston Island south to Padre Island, with Matagorda Bay being the preferred area. Karankawa were tall and athletic with a special affinity for living on the islands and lower waterways along the coast. They traveled between the various islands and bays in dugout canoes made from large trees. These canoes often extended 20 feet with a crude appearance, remaining bark covered and hewn flat on one side and blunted on each end. From these vessels, the Karankawa traveled the river bottoms and shallow lagoons in search of food. Typical dietary elements included fish, turtles, oysters, and alligators. Berries, nuts, persimmons, and, when available, sea bird eggs, supplemented this basic diet. For the most part, these Indians lived in camps along the bays usually clustered in groups of approximately 50 hovels. [10]

Although generally described as "fierce" and sometimes "cannibalistic," the Karankawa attracted the attention of many visitors to Padre Island and the Gulf Coast. Cabeza de Vaca is generally credited with first reporting their existence in 1528-1533 on Velasco Peninsula. Other reports appeared over the next few centuries, often accompanied by unflattering descriptions. Despite their reluctance to congregate around the early Spanish missions, the Karankawa survived well into the nineteenth century, leaving remnants of their material culture all over the coastal plains. [11] Several Karankawa camp sites are believed to remain on Padre Island, largely noted by oyster-shell middens that have been discovered by archeologists whenever sites are exposed by the shifting dunes.

European Exploration and Settlement

Spanish contact with both Indians and Padre Island came through exploration and accident. Alonso Alvarez de Piñeda, a Spaniard, first explored the Gulf Coast in 1519 searching for a suitable location for a new colony. After exploring and mapping much of the coastline, Piñeda traveled up the Rio Grande roughly 18 miles, reported aboriginal villages, and returned from the unsuccessful journey. The Spanish launched several other expeditions between 1520 and 1528, mostly to claim additional territory. The 1528 venture left only four survivors shipwrecked on the Velasco Peninsula on the upper Texas coast. Cabeza de Vaca, the best known, and the remaining three men wandered across the Southwest, ending their long journey in 1536. [12]

In 1554 an ill-fated journey from Vera Cruz to Havana en route to Spain lost all but one ship to a storm off Padre Island. The surviving 300 Spaniards landed near the Mansfield Channel and after a few days began a long trek south to Tampico, Mexico. Most of the survivors perished en route, some from the natural elements and others at the hands of the Karankawa. Several managed to escape and record their story of survival. A few months later, another Spanish expedition located the wreckage and salvaged part of the treasure. Eventually, the wreck disappeared under the sand and water off Padre Island, but was discovered more than 400 years later in 1964. [13]

In 1766, a second Spaniard, Don Diego Ortiz Parrilla, left San Juan Bautista and sailed through the mouth of the Nueces River, naming the bay Corpus Christi. Parrilla sent a scouting party across the Laguna Madre to Padre Island and then down to the southern end. He reported that Padre seemed unsuitable for military purposes or even cattle raising because the island lacked building material, fresh water, and grasses. [14]

The first European attempt to use the island was by the religious leader of Matamoros, Padre Nicholas Balli. A Catholic priest of Portuguese extraction, Padre Balli saw Isla Blanca or "White Island" for its potential as a cattle ranch. Between 1810 and 1820, Padre Balli and his nephew, Juan José Balli, initiated efforts to acquire a grant on the island from Spain. Although historians disagree, land records indicate that he received a grant for 11-1/2 square leagues, slightly more than 50,000 acres. [15] In 1827, Padre Balli and his nephew reapplied for the grant from the State of Tamaulipas, Mexico, being awarded such in 1829, some eight years after Mexico gained its independence. Their grant of 11-1/2 leagues exceeded the typical grant by at least one-half league. This excess, some historians feel, explained the dual title to the land. Padre Balli and his nephew began cattle ranching on the island from Rancho Santa Cruz de Buena Vista, roughly 25 to 30 miles north of the southern end of the island, outside the present National Seashore boundaries. When the Balli family reapplied for their grant, the new survey reported that Rancho Santa Cruz was the only inhabited part of the island. Padre Balli died in 1828, leaving his nephew with a fraction of the island, mostly contained on the southern end. The nephew continued raising cattle on the island until 1844. Afterwards, Juan José Balli left Padre and Texas on the eve of its annexation to the United States.

The remainder of the Balli grant eventually was acquired by José Maria Tovar. Tovar accumulated three leagues on the northern end of the island by his death in 1855. He followed in the tradition of the Balli family, operating his own cattle business. One half of Tovar's land and all but 7,500 acres of the southern end were acquired by Nicolas Guisante shortly thereafter. No information remains on Guisante or his use of the island. [16] If there were ever any physical traces of the Balli or Tovar operations on Padre Island, they have long since been completely obliterated. For many years during and after the Balli ownership, the island was called various names including Isla de Boyan, Ysla del Vallin, and Isla de Santiago. The name that served most people, however, became "Padre Island" in deference to Padre Nicholas Balli, the first permanent settler. [17]

American Contact and Settlement

In 1838 Henry Kinney left Pennsylvania to invest in the developing cattle industry of South Texas. The following year Kinney and William Aubry established the first trading post near Padre Island on what is now Corpus Christi Bay. Although little is known of Aubry and his later life, Henry Kinney became a successful rancher and made significant contributions to the development of the Corpus Christi area. Several years later, Phillip Dimmitt, James Gourlay, and John Southerland built their own trading post in what is now Flour Bluff on Oso Creek. Both trading posts prospered, though some historians surmise that the post may have served as a center for illegal trade with Mexico. [18]

Because of these trading posts, Padre Island gained attention beginning in 1845 during the Mexican War, after the Republic of Texas was annexed by the United States. General Zachary Taylor and more than 2,000 soldiers camped near Corpus Christi. In February 1846, Taylor sent a reconnaissance party to determine a route to Brownsville. The party returned finding no suitable way to cross the Laguna Madre at Brazos Santiago Pass. General Taylor then took a mainland route and established a supply base at Point Isabel, and built Fort Texas, later renamed Fort Brown, on the mainland across from the city of Matamoros. [19]

During the Mexican War and the subsequent western gold rush, Point Isabel and Corpus Christi became important supply stations. The trade possibilities in Texas attracted John Singer, brother to Issac Singer of sewing machine fame, in 1847. Singer, his wife, and son were shipwrecked in their vessel the Alice Sadell on Padre Island while en route to Point Isabel. The Singers were attracted by the island and bought part of the southern half of the island from the Balli heirs. The Singers established a profitable ranching operation and a home on the southern tip of the island, but they moved to Corpus Christi when the Civil War began in 1861. The Singers left behind a legend of buried gold and ranch buildings made of driftwood to be claimed by the sand of Padre Island. [20] During the mid-twentieth century, several visitors to the island claim to have discovered the Singer and Balli homesteads, calling them the "Lost City." Complete verification of this discovery has never been made.

In the post-Civil War years, the cattle business in south Texas boomed. Plants called packeries for processing cattle for their hides and tallow were built on Packery Channel south of Corpus Christi Pass, which divided Padre Island from Mustang Island. In 1854 Richard King of the mainland King Ranch bought 12,000 acres of the southern part of Padre Island from a Balli heir. In the 1870s, King and his partner Mifflin Kenedy leased more of the island and expanded their island ranching. At the peak of their involvement on Padre, there were nearly 70 people at the island headquarters, located at Santa Cruz, site of the old Balli place some 25 miles north of the southern tip. The King and Kenedy island operation was severely damaged by a storm in 1880 and the partners retreated to the mainland. [21]

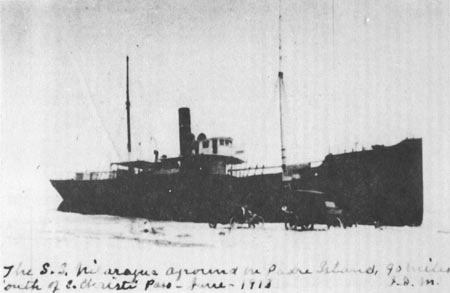

During the nineteenth and early twentieth century, Padre Island was the site of a number of shipwrecks. Near Big and Little Shell Beaches is a slight bend that became notorious for its shipwrecks. "Devil's Elbow," actually the point of tidal convergence, wrecked many otherwise seaworthy vessels. One of these was the Nicaragua. This ship, bound from Port Arthur for Tampico, Mexico, wrecked on October 16, 1912. The stern, its engine, and masthead of the vessel remained visible off the island for many years, serving as a landmark for down-island travelers. Many stories arose about the gun running and illegal activities it might have performed, but no one seems to know its true mission that October evening. [22]

|

| Figure 7. The Wreck of S.S. Nicaragua on Padre Island, June 1913. Photo courtesy PAIS Archives. |

Patrick Dunn's Ranching Empire

Patrick Dunn followed the Balli-Singer-King island ranching tradition. In 1879 the island's natural "fences" of water attracted his attention, and he leased part of the northern half of the island. He expanded his ranching operation and by 1926 the "Duke of Padre," as Dunn became known, owned almost the entire island. On two separate occasions Dunn built houses and lived on Padre Island, but his principal residence remained for many years in Corpus Christi. One of these houses was approximately one mile east of the 1927 causeway in a location he called "Owl's Mot."

Patrick Dunn raised mostly cattle, but there is some speculation that early on in his operation he also raised sheep. The livestock roamed over all of the island foraging grass at will. To facilitate rounding up the free-grazing cattle, Dunn built line camps of driftwood at 15-mile intervals the length of the island. He named them Novillo or Novia, Black Hill, nicknamed "Boggy Slough," and Green Hill. Remnants of the Novillo line camp can be seen today in the National Seashore, despite vandalism and the harsh environment of the island. These camps were used as collecting pens as recently as 1970, when the last grazing permit expired. [23] Dunn also built watering tanks, taking advantage of the shallow fresh water table behind the foredunes. He and his mostly Hispanic cattle hands sometimes built special camps giving them names of Campo Bueno, Borregas (sheep), Veneda (deer), and Barretos (saddle). [24]

Dunn's personality and life on Padre Island reached legendary status. Dunn often became the focus of local stories about his cattle drives and penning, encounters with visitors and wildlife, and treasures he collected from the Gulf. In the final years of Dunn's ownership, he became especially resentful of the growing popularity of the island and maintained posted signs along the island. One writer described Dunn's antipathy for fishermen as "Fishermen meant sports, sports meant tourists, and tourists meant civilization coming too close to Padre." In 1927, Dunn lamented to a Corpus Christi reporter what he must have seen as inevitable:

Padre Island was the best cow ranch in the world when I came to it forty-eight years ago! That's a broad statement I know, but it's a good ranch now. Twenty years from now it may be a better cow ranch. If the Lord would give me back the island now, wash out a channel in the Corpus Christi Pass thirty feet deep, and put devilfish and other monsters in it to keep out the tourists, I'd be satisfied. [25]

Patrick Dunn died in 1935 not knowing that tourists would soon occupy his island forever.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

pais/adhi/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 14-Jun-2005