|

Padre Island

An Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER ONE:

INTRODUCTION

Location and Setting

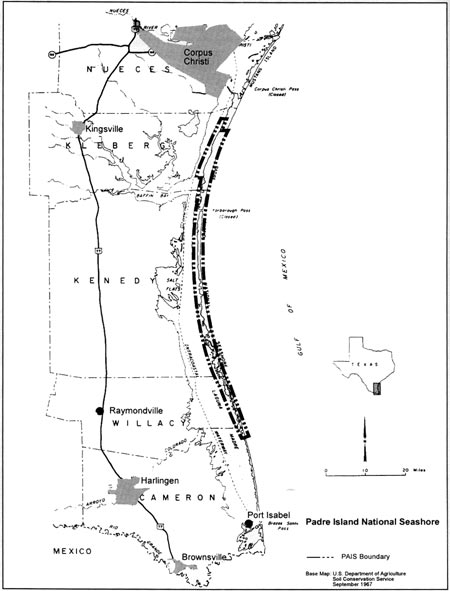

Padre Island National Seashore occupies the central 66 miles of the approximately 113-mile long Padre Island in South Texas. Stretching from just south of the Nueces County line on the north to the northern end of Willacy County on the south, the National Seashore includes portions of Kleberg, Kenedy, and Willacy Counties, with the majority of the park in Kenedy County.

Padre Island is the longest natural barrier island along the Gulf of Mexico coastlines. The chain continues south to include Brazos Island at the mouth of the Rio Grande, separated by the Brazos Santiago Pass, and north to include Mustang Island, once separated by Corpus Christi Pass, and St. Joseph's, Matagorda, and Galveston Islands. Mansfield Channel, a shipping channel dredged across Padre to Port Mansfield in Willacy County, breaks the natural length of the island.

|

| Figure 2. Map of Padre Island National Seashore. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Padre Island divides into two geographic areas: North and South Padre. Mansfield Channel serves as the physical separation between the two areas. Padre Island National Seashore lies largely on North Padre Island, leaving the extreme northern end of North Padre and almost all of South Padre in private ownership. Land immediately adjacent to the park boundaries on the north and across the Mansfield Channel on the south remains undeveloped. Privately owned land on both ends of Padre Island currently supports various types of development including subdivisions of single-family houses, high-rise condominiums and hotels, and assorted retail and service businesses supporting the regional tourism industry.

Mean low tide or two fathom line (12 feet deep or roughly one quarter of a mile from shore) forms the eastern boundary of the park; the eastern edge of the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway down to Baffin Bay and the western-most line of dry land forms the western. On the west, a shallow lagoon, the Laguna Madre, varies from several hundred feet to more than six miles wide. On the western edge of the Laguna Madre, the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway follows the mainland as part of a full Gulf coast commercial transportation route. The Laguna Madre, the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, and a number of small inlets and bays, separate Padre Island from the mainland that it guards.

Padre Island National Seashore contains roughly six management areas: North Beach, South Beach, Little Shell Beach, Big Shell Beach, the down-island primitive beach area, and Bird Island Basin. North Beach fronts the Gulf of Mexico at the northernmost end of the National Seashore for five miles. Its wide, flat white sandy beach provides the focus for the Malaquite Beach Area and access to the Bob Hall pier and Padre Balli County Park north of the park boundary. The majority of North Beach is closed to vehicular traffic to provide a control area for observance of natural processes.

Bird Island Basin forms another area west of North Beach along the Laguna Madre. Named for North and South Bird Islands that it encompasses, the basin stretches for approximately ten miles. Tidal flats, mud flats, and grasslands predominate. Bird Island Basin possesses some of the deepest water in the Laguna Madre and may be used by motor boats. North and South Bird Islands are natural formations that host ideal habitats for waterfowl. A line of spoil islands, formed from the disposed dredging of the Intracoastal Waterway, lie to the west of the Bird Islands. The basin's varied topography contributes to the rich ecological environment and vital wetlands for which it is known.

South Beach on the eastern side of the island begins at the end of Park Road 22 and extends for ten miles, denoted by a marker every five miles. It is similar in appearance to North Beach but gradually becomes narrower and contains softer sand after five miles. Vehicles are allowed on South Beach, but only four-wheel drive vehicles may continue past milepost five on the beach.

South Beach continues into Little Shell and Big Shell Beaches, the narrowest section of Padre Island. These two areas possess steep beach embankments that rise to tall foredunes. Because the Gulf tides converge along these beaches, they are known for the large number of fine, unbroken sea shells. Both Little Shell and Big Shell Beaches are approximately ten miles in length, and while open to four-wheel drive vehicles, are not always accessible because of high water. At mile marker 15 on Little Shell Beach, vehicles may drive across the island to the Laguna Madre via a shell road at Yarborough Pass. Yarborough Pass, however, is a manmade channel reclaimed by the active island processes and may be inaccessible during high tides.

The lower 30 miles of the National Seashore, from mile marker 30 to mile marker 60, are considered "down island." The down-island area possesses the National Seashore's more primitive facilities and pristine appearance. Its wide, white beaches and tall foredunes become broken by extensive washover channels and low-lying tidal flats. The Island extends to some of its widest points in this section. The Mansfield Channel serves as the southern boundary of the down-island area and the National Seashore.

Access

The northern end of Padre Island National Seashore lies approximately 30 miles southeast of downtown Corpus Christi and 18 miles southeast of the community of Flour Bluff. Flour Bluff is the home of the Corpus Christi Naval Air Station and the headquarters of the National Seashore. Interstate Highway 37 goes through Flour Bluff and leads into South Padre Island Drive, Highway 358 (from the junction of the Crosstown Expressway), and Park Road 22. Park Road 22, maintained by the State of Texas, provides a generous two-lane hardtop drive directly into the north end and principal entrance to the Seashore. Vehicular access is only available at this entrance. A narrow two-lane hard-topped road continues into the park concluding at the northern end of South Beach with a feeder road to the east allowing access to North Beach and another one to the west for access to Bird Island Basin.

On the southern end, the National Seashore is approximately 50 miles from Brownsville via the Isabella Causeway, Port Isabel, and the City of South Padre Island. Some 20 miles of the 50 are roadless and lie between the City of South Padre Island and Mansfield Channel. No vehicular access is currently available to the southern end of the National Seashore from Port Mansfield or South Padre Island.

The National Seashore offers no airfield for commercial or private airplanes. Although much of the park may be reached by boat, there are neither marinas nor docking facilities within its boundaries. Boats may be launched or loaded, however, at Bird Island Basin in the northern end of the park.

Facilities and Infrastructure

Five areas of the park contain facilities; one is outside the park boundaries. Malaquite Beach includes the largest and most frequented facilities. A visitor center, observation deck, concession operation, restrooms, showers, changing rooms, and a large paved parking lot comprise the majority of the park buildings and structures located on the western edge of the foredunes. Beach access is available by raised wooden walkways across the dunes. The Malaquite Beach Campground, adjacent to the complex, contains more than 40 campsites, picnic tables, restrooms, cold showers, and a sanitary dump station. Other nearby park facilities include an observation and water tower, two ranger housing units, and water treatment plant. Most of the ranger interpretive staff are based at the Malaquite Beach facility.

Bird Island Basin, the second park area with facilities, includes a boat launch and primitive camping. Yarborough Pass, near mile marker 15 on the Laguna Madre, also offers a primitive campsite with chemical toilets and picnic tables, but no fresh water.

The final park facility within the boundaries is the Gulf Ranger Station, approximately three miles beyond the National Seashore entrance. A large trailer serves as offices for park rangers and support staff. A collection of work and vehicular sheds and various wooden frame outbuildings complete the Gulf Ranger Station complex.

The primary administrative facility for Padre Island National Seashore is located in Flour Bluff. This headquarters building provides offices for the park superintendent and administrative staff. In addition, the park archives and collections and records are maintained at the headquarters. The National Seashore works in cooperation with the City of Corpus Christi Convention and Visitors Bureau to offer information and assistance to visitors in the lobby area.

Scenic and Recreational Opportunities

Padre Island National Seashore represents of one of the largest and most pristine seashore preserves in the United States. As such, it offers incomparable scenic and recreational opportunities year round. Visitors come from all over the United States and foreign countries. The largest number of visitors is from within a 250-mile radius of the National Seashore, mostly from non-urban areas. [1] Visitor profiles indicate that a broad demographic spread exists with a significant population of Hispanic visitors. [2] For the 14-year period between 1976 and September 1989, the average annual visitation was 645,209, with the highest year being almost one million in 1976. [3]

Visitors come to Padre Island for a myriad of reasons sometimes reflected in the month of visitation. Those interested in beach activities increase the visitation counts during the summer months and mostly on weekends. June, July, and August tend to be the busiest months of visitation; Saturday and Sunday are the most popular days of the week. Many of the summer visitors use the Malaquite Beach facilities. In recent years, however, Bird Island Basin increased in popularity with a high number of boat users and windsurfing enthusiasts. Fishing is popular all year along both the Laguna Madre and the seashore and contributes to at least a minimal number of visitors throughout the year. Winter Texans, largely senior citizens, are increasing in numbers between December and April. Bird Island Basin hosts many seasonal visitors, thereby increasing the numbers of recreational vehicles housed there during the winter. [4]

Many forms of passive and active recreation are available in the National Seashore. Swimming and sunbathing combines as one of the most popular activities. Although these are permitted along any of the beaches, Malaquite Beach is the best beach area and offers lifeguards during the summer months. Surfing is also popular but not allowed on the designated swim beach of Malaquite Beach.

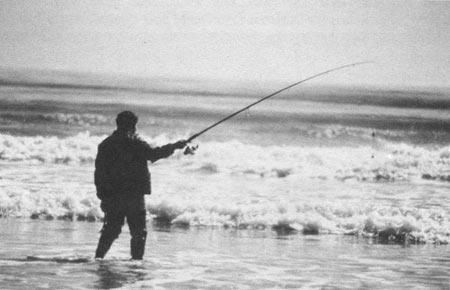

Other water sports such as boating, waterskiing, and sailboarding or windsurfing occur in the Laguna Madre. Small power and fishing boats, and some sailboats, use the Laguna Madre especially during the summer months. In recent years, windsurfing has become another popular activity. Bird Island Basin is now considered one of the best three windsurfing areas in the country. Fishing and shelling are arguably the oldest recreational activities on Padre Island. Visitors fish year round with surf fishing and seining being the most popular. Redfish, speckled sea trout, black drum, and whiting generally come from the Gulf side; sheepshead, croaker, and flounder are found in the Laguna Madre. Visitors also engage in shelling. Long before the establishment of the National Seashore, shell enthusiasts combed the shoreline, sometimes developing significant collections of unique seashells. Shelling continues as a timeless recreational activity for all age groups.

Many visitors to the National Seashore enjoy hiking. The first opportunity in the park is along the Grasslands Nature Trail less than one-half mile after the entrance station. A written guide introduces the hiker to island vegetation, animal life, and barrier island dynamics. Beach hiking is also popular. With the exception of the dunes, hiking along the beach is allowable anywhere in the park. Hiking affords an opportunity to watch for the many native birds on the island and comb the beach for shells.

Camping and picnicking are other island activities. Several campgrounds with facilities are provided, but primitive camping is allowed all along the Gulf beach and in designated areas on the Laguna Madre. Picnic tables are found in several locations, but picnicking is allowed anywhere on the beaches.

Driving along the beach is another popular activity. All "street legal" vehicles are allowed on park roads and the first five miles of South Beach. Four-wheel drive vehicles may continue down island to Mansfield Channel. The drive sometimes includes segments of difficult terrain but visitors may check with the Ranger's Station for driving conditions. Driving is never allowed on the dunes.

|

| Figure 3. Windsurfing at Bird Island Basin. Photo courtesy PAIS Archives [252]. |

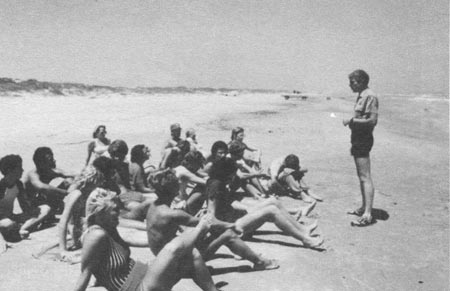

Interpretive Activities

Although the park's principal purpose is recreation, it sponsors year round interpretive activities. Environmental education programs constitute the majority of interpretive work either internal or external. Internal programs include organized nature walks on North Beach, evening campfire talks on North Beach and at Bird Island Basin, and a display and audiovisual programs on Padre Island history and resources at the Malaquite Beach Visitor Center. A special internal program for children introduces environmental issues through a puppet show, and art and writing exercises. Wayside exhibits and the Grassland Nature Trail offer interpretation to visitors in a more passive format. External education programs primarily focus on children and schools. The park's "traveling trunk" show may be used to tell the history and natural resources of Padre Island through selected objects.

A team of permanent park rangers coordinate the interpretive program in the Division of Interpretation. Seasonal park rangers and technicians assist during the late spring and summer months to handle the large number of visitors. In recent years, the Division of Interpretation expanded its educational materials and programs to attract the bilingual public. The Malaquite Beach Visitor Center houses most of the Division of Interpretation staff members and facilities. A small bookstore operates at the Center as well in cooperation with the nonprofit Southwest Parks and Monuments Association.

National Park Service Administration

The National Park Service serves as the guardian and steward of Padre Island National Seashore. Through a network of regional offices, the Park Service administers more than 360 national park units; fourteen are designated as a national seashore or lakeshore. Padre Island National Seashore comes under the direction of the Southwest Regional Office, in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and is the only seashore in the region. At the time it was designated in 1962, Padre Island represented the Regional Office's easternmost park unit and remained such until the designations of the Big Thicket National Preserve and Jean Lafitte National Historical Park. It also was one of the few non-desert units balancing recreation with resource conservation in the Southwest Regional Office. Padre Island's unfamiliar or simply unknown characteristics and potential for economic speculation contributed to the delayed recognition of the island as a worthy "national" treasure. After Congress and the president approved the Park, Parkway, and Recreational Area Study Act in 1936, outdoor recreation became the responsibility of the National Park Service. Over the next 30 years, the Federal government designated its first seashore recreational parks in the consecutive order of Cape Hatteras, Cape Cod, and Padre Island National Seashores. The Park Service then focused on learning about the dynamics of this barrier island and how to manage it simultaneously as a recreational destination and fragile natural resource. These challenges and how they have been met by Park Service employees form the basis of this administrative history.

|

| Figure 4. Fishing in the Gull of Mexico. Courtesy PAIS Archives [No. 528]. |

Since designation in 1962, nine superintendents and hundreds of full- and part-time men and women have promoted and protected Padre Island National Seashore. There are currently approximately 50 full- and part-time employees involved in five administrative divisions: administration, law enforcement, resource conservation, interpretation, and maintenance. Many National Seashore employees transferred to Padre Island from other park units while some began and ended their careers here. All who have worked at the seashore have met a complex environment difficult to understand quickly. Popular architectural designs and building materials deteriorate rapidly in the harsh coastal world of South Texas. Visitor interpretation programs and recreational activities successful in other parks sometimes fail at Padre Island. Even resource conservation practices employed at other national seashores have met an untimely fate at Padre.

In many aspects, the Park Service through its many employees has matured in its management of Padre Island during the first two decades and perhaps even profited from the experience. After several unpredictable storms, environmental catastrophes, and resource losses, the Park Service learned that management of the island required understanding the island's dynamic mature and vulnerability, rather than manipulating it. Management plans for Padre Island National Seashore in the 1990s reflect utilization of the resources and environment that makes human occupation, if not subordinate, at least one of mutual respect.

|

| Figure 5. Ranger Program. Courtesy PAIS Archives [No. 422]. |

Popular Images of Padre Island

Although largely uninhabited for much of its history, Padre Island attracted and captivated many people over the years who in turn contributed to the popular image of the island. Sometimes the images were based on fact and other times not. Long-term residents like Louis Rewalt came to know the island through years of close association. After more than 50 years of residence, he amassed a sizeable collection of artifacts combed from Padre's beaches. Editors of the Saturday Evening Post magazine labelled Rewalt in a 1948 issue as the "hermit of Padre Island." He, like many others, saw Padre Island as a backdrop for tales of Indian life and buried gold. Another local devotee of Padre was Vernon Smylie of Corpus Christi. Smylie wrote four booklets during the 1960s focusing on Padre Island: Padre Island, Texas (1960), Conquistadores and Cannibals (1964), This is Padre Island (1964), and The Secrets of Padre Island (1964). Smylie offered his readers am array of stories surrounded by tidbits of history, all in a folksy tome. After the invention and popularity of metal detectors, a whole new wave of enthusiasts appeared on Padre's beaches. One of these, William Mahan, composed stories of his treasure hunting in a book entitled Padre Island, Treasure Kingdom. Much to his chagrin, Mr. Mahan's treasure hunting ended during the 1960s, at least within the boundaries of Padre Island National Seashore, because of Federal laws prohibiting the removal of artifacts from public lands.

Many other writers also found Padre Island charming and inspirational. Dorothy Hogner devoted an entire travel book to the automobile trip from New York to Padre in South to Padre, published in the 1930s. Her candid and amusing story, illustrated by her husband and travel companion, brought national attention to the isolated beaches and coastal life of South Texas. Mary Lasswell, native Texan and author of I'll Take Texas (1958), mentioned Padre Island's natural resources in her pursuit to educate Texans on their natural wonders. During the 1930s Works Progress Administration (WPA) writers project, the Federal government employed a number of writers to make Padre Island the focus of the only Federal Writer's Project round table in Texas. More than a dozen authors wrote of Padre's history, people, and environment. Although not published until 1950, the writer's round table developed a supportive audience for Padre Island across the State.

Padre Island's captivating landscapes and resources also attracted other talent. Photographers such as Corpus Christi's Doc MacGregor recorded several decades of Padre Island life. Many of his photographs depict beach scenes, fishermen in seining parties, wildlife, and dune field landscapes. Famed Texas regionalist artist Everett Spruce made an almost annual visit to Padre during the 1950s and 1960s capturing the seashore on vivid canvases and in sketches. His work and that of other artists appeared in a publication in the 1980s revealing the more spiritual side of Padre's coastal life.

For the more serious visitor, Padre Island offered a vast laboratory for investigation. Numerous marine biologists, geologists, archeologists, and historians came to the island with a curiosity but often left in awe of the overwhelming environment. Two master of arts candidates prepared theses on Padre Island's history. Pauline Reeve completed the first history in 1938 at the Texas College of Arts and Industries in Kingsville, Texas; Robert Meixner completed another history in 1948 at Southwestern University in Georgetown, Texas. Corpus Christi marine biologist, Henry Hildebrand, chronicled years of marine life on the shores of Padre and in the Laguna Madre. Geologists F.M. Bullard and W.A. Price studied sediments and development of Padre Island and the surrounding region during the 1930s and 1940s. As these scholars answered one set of research questions, they uncovered another handful that continues to be studied even today.

Whether collecting shells on the beach or scientific specimens from the Laguna Madre, Padre Island is a land of adventure that seems to instill passion for its beauty among visitors. Although not considered a "popular" enterprise as those given above, Padre Island maintained a steady spell on many politicians and community leaders over the years. Oscar Dancy, Cameron County Judge, and William Neyland, Corpus Christi civic leader, are two of those. Ralph Yarborough, United States Senator (1957-1971) from Texas, became the most important supporter. Yarborough receives credit for sponsoring more than four years, and finally passing, legislation to designate Padre Island National Seashore in 1962. After Padre Island, Yarborough promoted other conservation projects in Texas. During his two terms in the United States Senate, Yarborough led the fight for other National Park Service units including Guadalupe Mountains National Park, Fort Davis National Historic Site, the Alibates Flint Quarries National Monument, Amistad National Recreation Area, and Big Thicket National Preserve.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

pais/adhi/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 14-Jun-2005