|

Padre Island

An Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER SIX:

MANAGEMENT AND PLANNING ISSUES 1970 - 1980

Malaquite Beach Pavilion and Facilities

Shortly after completion of the Malaquite Beach facilities in late 1969 problems arose with the construction. Small hairline cracks appeared along the concrete pillars supporting the public use building, boardwalk, and view tower. When the new superintendent James McLaughlin arrived in May 1970 from the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, park personnel already reported the pavilion as a maintenance concern. Within a few years Superintendent McLaughlin and staff redefined the beach facilities as a long-term problem. [1]

In 1971 the Texas Society of Architects honored Victor Brock and Leslie Mabrey for their design of the Malaquite Beach facilities. Brock and Mabrey brought years of experience with the coastal environment to the design of the facilities. They knew of the extreme temperatures, strong winds, salt spray, and the strength and destructive force of hurricanes. For the incorporation of these concerns with the design, the architectural firm also received recognition from the Corpus Christi Chapter of the American Institute of Architects in 1973. [2]

The award-winning status of the facilities complicated early recognition and publicity on the maintenance problems. Newspaper reports emerging in June 1973 blamed neither the architects nor the construction company, but concluded that all problems were typical of pre-stressed concrete buildings along the coast. Superintendent McLaughlin repeated the "no blame" story yet described the problems as "long-term." He added that the Padre Island problems were the most severe conditions seen by the Park Service at any of the national seashore parks. [3]

McLaughlin's public statements conflicted with comments in his fiscal year 1972 annual report. He cited two reasons for the maintenance problems: location in the foredunes and construction defects. Regarding the location, McLaughlin stated one of the most insightful comments yet made by a Park Service authority, "The Gulf Coast environment is deceptive in ways which we have yet to understand." In short, McLaughlin acknowledged the complex environment of Padre Island and that its intrinsic nature eluded the Park Service management. Regarding the construction defects, he said that a construction oversight allowed the steel reinforcement bars to be placed too close to the surface of the concrete in the walkways and supporting columns. This mistake caused rusting and swelling from the salt and moisture which in turn caused the concrete to crack and break away. [4]

In May 1972, Paul Gerrish, the new maintenance supervisor, reported additional problems with the Malaquite Beach complex. Hurricane shutters around the windows of the concession portion of the public use building disintegrated and rusted beyond repair. Drinking water dispensers on the outside of buildings also rusted. Light fixtures along the boardwalk made of aluminum disintegrated. Each light fixture cost over $100 to replace, amounting to over $8,000 for all 72. Gerrish made two important statements on the facilities:

It is unfortunate that when this building was planned, an adequate study was not made to provide a building plan that could be adequately maintained without having to replace so many costly fixtures every three years. In the master plan, it is planned to extend the present Malaquite development which I think would be a mistake. Take a long look at the problems we are facing with the present building and you may want to change a lot of things. We are falling behind in trying to maintain what we have now and with more maintenance in this corrosive atmosphere, we would be incapable of doing it. [5]

The reports of Superintendent McLaughlin and Gerrish drew the attention of Park Service personnel, making the Padre predicament "one of the most unusual maintenance problems in the National Park System." [6] When Bob Pozol of the Southwest Regional Office visited the National Seashore in August 1972 for an his own inspection, he added new structural problems to the list. The center stairway of the concrete walkway leading to the pavilion had broken away from its foundation. Two kiosks in front of the pavilion fell from their foundations because of the high winds. Finally, the 300,000-gallon concrete water reservoir underneath the View Tower showed hairline cracks and seepage like the other concrete structures at Malaquite Beach. [7]

By 1973 the Malaquite facilities attracted attention from outside the Park Service. Local newspapers carried stories on the deterioration, noting that the cracks posed no harm to visitors. [8] As the public and Park Service became increasing sensitive to the problems, the budget for maintenance improved. Superintendent McLaughlin reported in 1973 that the National Seashore received $50,000 for a pilot program to start repairing or stabilizing the deteriorated concrete. After consultation, Park managers chose to chip and fill the exposed spots as a means of stabilizing the structure. This project became known as the "Malaquite Stabilization Project" and proved to be laborious but inexpensive. [9] Stabilization efforts begun in 1973 intensified in 1974-1975. In 1974, a new Chief of Maintenance, Sheldon Smith, created an epoxy-type process to hold the concrete together. The epoxy application worked well, and after a full-time concrete finishing foreman was hired in February 1975, work progressed rapidly. By the end of 1975, he completed approximately 50% and by 1976, 95% of the work on Buildings A and L was completed. [10] Two years later, the Park Service recognized Sheldon Smith with a commendation estimating that his epoxy process saved approximately $94,792. [11]

In spite of the Maintenance Division accomplishments during the late 1970s, the Malaquite Beach facilities never seemed to reach their full use or capacity. As Buildings A and L neared stabilization in 1976, the View Tower deteriorated rapidly. Park personnel reported that funds set aside for the Malaquite facility were exhausted by the end of Fiscal Year 1978 and nothing remained for the repairs on the View Tower. Without funds, park staff decided to perform a load test on the structure before proceeding with any work. [12] Without a decision, the following July 1979, unusually strong winds eroded sand below walkways and along the platform supports of the Malaquite Pavilion, creating new maintenance and structural problems. Although repaired with "mudjack," the pavilion's foundation remained vulnerable to the island's natural processes. [13] The Malaquite Beach complex continued to be a problem into 1980, but the Park Service remained unable to resolve its structural problems.

|

| Figure 19. Aerial View of Malaquite Beach Pavilion. Photo courtesy PAIS Archives [T1056]. |

Grazing Permits

In the summer of 1970 Superintendent McLaughlin met with David Coover, a representative of the Dunn ranch, to discuss the continuation of cattle grazing. A "gentleman's agreement" between Senator Ralph Yarborough and National Park Service Director George Hartzog in 1965 allowed grazing permits to continue on Padre Island for five years, ending December 31, 1970. [14] By midyear 1970, McLaughlin and the cattle owners either needed to bring an end to the agreement or negotiate a new one. Although Dunn's cattle empire had existed for over a hundred years at that point, environmentalists and resource conservationists demanded that it end. One conservationist reported that "the mosquitoes drive these cattle onto the beaches to sleep at night and in the morning these public beaches look like the holding pen for a slaughterhouse." Other environmentalists argued that the cattle rooted up young, tender grass that led to the de-stabilization of dunes and thus the island. [15] McLaughlin and his staff increasingly found themselves in a difficult position. While public sentiment might support the environmentalists' position, Coover and his ranching associates knew of Federal policy on public lands in the West that allowed grazing and offered a plausible argument and response for every public comment expressed. [16]

Coover detailed his position in a letter to McLaughlin on July 17, 1970. He asked for an extension through the fall of 1973 for complete removal and hinted at a full two-year lease agreement. The working pens below the first set at the Novillo Line Camp, he explained, needed extensive repair and required expensive four-wheel drive vehicles to work the area. A partial lease at the northern end of the island would be acceptable to him for the short remaining period. Because of the poor calf crop produced on the island, losses from hurricanes, and poor grass quality, Coover added that a continuance of the lease rate or at most 25 cents per unit was reasonable. In response to public comment on the detriment of cattle droppings, he reminded McLaughlin of the many parks full of wildlife and that to some visitors the cattle became an added attraction. He responded differently to the charge that the cattle led to denudation of grasses and dunes. Coover argued that camping, vehicular traffic over dunes, and Navy bombing resulting in grass fires left more problems than cattle grazing for over 150 years. [17]

McLaughlin delayed a response to Coover's July 1970 letter so that he could study the situation. Coover, however, became impatient with McLaughlin's delay and took his case to a deputy director of the National Park Service in Washington, DC. In a report from Washington in late summer 1970, the Park Service indicated that negotiations were underway with David Coover for a new two-year lease but with some restrictions on "free-roaming cattle" and a progressive reduction in their numbers. [18]

As the deadline for the grazing permit neared, the issue received more public attention. In a news release on September 4, 1970, Secretary of Interior Walter J. Hickel ended the controversy by denying a request to continue the lease. He continued that "cattle grazing is not compatible with preserving the natural values of the Seashore nor with its full enjoyment by the public." On December 31, 1970, the days of cattle grazing on Padre Island officially came to an end. [19] By late fall 1970, local newspapers reported that most of the 1,200 head of cattle were removed. Park Rangers, however, remembered that four cows remained through the 1970s with the last one being removed in the early 1980s. [20]

Master Plan Development

Within two years after arriving at Padre Island National Seashore, Superintendent McLaughlin initiated a new master planning process. The Master Plan Brief released in 1965 no longer seemed applicable for the development of the National Seashore and new Federal legislation required all units of public land to evaluate the potential for wilderness protection. Because of funding limitations and property owner court settlements, the Park Service reduced the size of the National Seashore from that authorized in 1962. It also became clear that both the physical plant projections and operating policies needed adjustments. In the fall of 1971, McLaughlin and staff welcomed a special planning team from the Denver Service Center. Led by park planner Marc Malik, the team members included a wilderness specialist, sociologist, ecologist, and interpretive planner. The remaining park staff, concession manager, and a research associate offered consultation as requested by the team. [21]

In large part, the planning team found many of the old issues involving Padre Island still unresolved. North Padre Island supporters sought more restrained development of the island, while the southern end wanted development that would benefit Rio Grande Valley residents. The southern supporters repeatedly pointed to the Malaquite Beach facilities and park headquarters as an indication that the northern end received preferential treatment. Both ends, the park planners pointed out, already had extensive state, county, and city park facilities. In short, the planners seemed sympathetic to the concerns of area residents but wanted their needs to be met in a manner that would not destroy the natural resource of Padre Island. This, of course, had to be done in light of what appeared to be the growing popularity of the National Seashore. The planners reviewed visitation records showing an increase from 361,000 in 1968 to 904,000 in 1971. For the time being, it seemed, the National Seashore was attracting a growing and unlimited number of visitors. [22]

The planners stated early in the draft that the underlying concept for recreation on the island was "to give the visitor a broad range of opportunities to experience the various features of the island in a manner that is not available to him at the existing seashore parks in the region." In other words, the planning team wanted to see diverse uses on the island away from the existing "high-density bathing use, with easy access and many concessioner services." The greatest value of the National Seashore, they determined, was its "endless stretches of primitive beach and interior lands." Similar areas outside of the park were expected to disappear as the north and south ends continued development like the present. [23]

Several aspects of the new plan seemed to repeat parts of the plan from the 1960s. Malaquite Beach development would continue to expand, Laguna Madre access would be improved, and recreational facilities would be provided at the southern end. Other parts of the plan, however, differed from the earlier version. Although recreational facilities on the south were planned, all beach facilities, camping provisions, and a boat dock would be immediately south of Mansfield Channel. Since this land was not owned by the Park Service, the plan suggested a property swap with the two parcels still owned farther south to gain some 200 to 300 hundred acres. [24]

The most radical changes involved transportation routes and systems. The plan called for the road system, at this point ending north of Little Shell Beach, to extend 15 miles to a trailhead at Yarborough Pass. This extension allowed Little Shell Beach to be closed to vehicles for 12 miles. At the southernmost end of Little Shell to the Mansfield Channel, approximately 45 miles, the plan envisioned no development except what would be required for a beach bus system. Under this scheme, buses traveled the length of the island and provided visitor access to the remote sections, especially Big Shell Beach. Planners felt that this route and a short-term one from Malaquite Beach to Little Shell Beach expanded the average visitor's experience on Padre Island. In an accompanying development, the plan called for boat access west of Malaquite Beach, now known as Bird Island Basin, at Yarborough Pass, and finally on the Mansfield Channel. The planners also requested that areas south of Big Shell Beach to Mansfield Channel be managed as a Class V primitive area allowing only primitive campsites, shelters, and sanitary facilities. [25]

While the Denver Service Center team worked, the Wilderness Planning Team responded to Public Law 88-577, passed in 1964 establishing a National Wilderness Preservation System. Under this law, Federal planners evaluated all roadless areas of 5,000 acres or more within national parks or national monuments for "wilderness" designation by 1974. A wilderness designation exceeded current administrative planning designations for outdoor recreation areas ranging from a Class I high density area to a Class V primitive area and Class VI historic and cultural area. The Wilderness Planning Team's main points became to reduce development and set restrictions for public use. Padre Island National Seashore held over 5,000 acres in its central portion and thus required consideration of its wilderness potential. [26]

In 1972, the National Seashore released and disseminated to the public the Master Plan, Environmental Impact Statement, and Wilderness Proposal. Padre Island supporters stepped forward to review the proposed plans. The Resource Conservation and Open Space Development Committee of the Coastal Bend Council of Governments became one of the first public entities to comment. At two February 1972 meetings, committee members discussed the new park proposals with Superintendent McLaughlin at length. The committee's discussions turned to the old question of mineral extraction on the island. McLaughlin, favoring the Park Service recommendation to leave the area 35 miles south of Malaquite to the Mansfield Channel as "primitive," felt that as long as the Park Service allowed mineral extraction, a "wilderness" designation was prohibited. In response, members of the committee, apparently wanting "wilderness" designation, asked if an exemption might be requested to change the Park Service policy. The committee voted to request an exemption for the mineral extraction and seek wilderness designation. In a final request, the committee added that they would like to recognize the small oak groves on the Laguna Madre as an "outstanding natural area." [27]

Within a month, on March 23, 1972, the Park Service received a different opinion of the National Seashore's use in a public hearing in Brownsville. South Texas supporters wanted the area south of Malaquite Beach to Mansfield Channel, roughly 35 miles, to remain as a "primitive" area, not "wilderness." However, the roughly 25 to 30 Brownsville citizens present seemed most interested in the proposed development adjacent to the Mansfield Channel. Once again, the Park Service presented a conceptual plan for development south of the channel but had neither funds nor the land acquired to follow through with the concept. South Texans, however, seemed willing to accept the concept and allow the Park Service time. Other than general comments on the plan, the group voiced almost no opposition to the planning documents. [28]

|

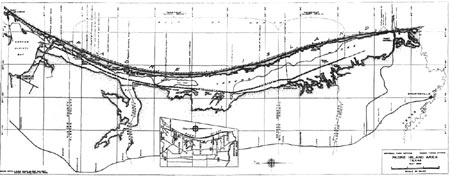

| Figure 20. Map of Padre Island National Seashore. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

On March 25, 1972, McLaughlin and staff opened similar discussions in Corpus Christi. While the Park Service planned its discussion and formal public hearing, a vocal group of citizens banded together to oppose the Master Plan and wilderness designation. The owner of an arguably "illegal" cabin on the island, Leslie Chappell, urged citizens to come to the hearing and oppose the Master Plan. Chappell, who found the provision to close vehicular traffic on Little Shell Beach and divert traffic particularly objectionable, would later reveal that his cabin was very close to the proposed closed beach, thereby eliminating his access. [29] As the discussion and hearing unfolded on Saturday, March 25th, the cabin owners and conservationists separated. [30]

While the discussion ensued over the cabins, the Park Service proceeded with its plans. On September 21, 1972, the president reported to the Congress the Park Service recommendation: Padre Island was unsuitable for wilderness designation. In its final statement, the Park Service included all land south of Yarborough Pass as a Class V "primitive" area under the existing outdoor recreation land classifications. By the end of calendar year 1972, the Park Service approved only the Wilderness Proposal. [31]

In 1973 the Denver Service Center returned to the Master Plan for revisions. At the same time, park staff revised and forwarded to the regional office and Washington a new Environmental Impact Statement. The National Park Service, however, required the Environmental Protection Agency to accept the work before the Master Plan could be formally approved and adopted. In the meantime, South Padre Island Development Corporation offered to give the Park Service 200 acres adjacent to the Mansfield Channel on the south side in exchange for the 18 acres owned by the Park Service farther south. By the end of the year, the company retracted its offer because the Park Service would not begin development on the southern end as proposed in the Master Plan. [32] During the next year, the Environmental Impact Statement and Master Plan were approved on May 22nd and October 21, respectively. The approval of these documents allowed the Park Service to continue development in Padre Island National Seashore.

Spoil Islands Cabins and Chappell Cabin

The problem of the spoil islands cabins and the Chappell cabin had emerged in the weeks prior to the public hearing in March 1972. Newspaper stories, editorials, and countless accusations led to the inevitable public confrontation. While the discussion centered on vague statements, development and use of the cabins had begun a number of years ago. As a result, great pride and loyalty existed among the various owners.

Dredging in the Laguna Madre for the Intracoastal Waterway in 1939 left a series of small landforms called "spoil islands" or "spoil bank islands." These extended south from immediately below South Bird Island in Nueces County into Kleberg County on the eastern side of the Waterway. Because the boundary of the National Seashore as authorized extended to the eastern edge of the Waterway, the spoil islands became Park Service property when the majority of park land was acquired by condemnation in 1966. These man-made islands, unlike the natural North and South Bird Islands, consisted of various combinations of sand, mud, and shell acquired from the adjacent channel. All of them changed under the forces of wind, rain, and wave action regardless of composition. Some developed ponds of water and vegetation. Many became habitats for water fowl and wildlife. [33]

Between construction of the Intracoastal Waterway and the 1960s, a handful of fishermen and island enthusiasts from the Corpus Christi area built small wooden frame cabins on the spoil islands. Although estimates varied in 1972, approximately 200 such cabins offered weekend vacation homes for the owners. Many of these were constructed over water and none provided sanitary or fresh water facilities. In a July 1972 survey, 75% or 115 of the total number of cabins fell within the boundaries of the National Seashore. An increasing number appeared run down and uninhabited. [34]

The issue of what to do with the cabins plagued the Park Service from the beginning of land acquisition. In order to placate owners and in the absence of the time or money to devote to the endeavor, Padre officials allowed the owners to continue their use by granting special permits. By 1972, Superintendent James McLaughlin could no longer sidestep the presence of these cabins. In a series of meetings on the proposed Master Plan, the two opposing views emerged to debate. Environmentalists declared in public testimony that the cabins must go. Cabin owners retorted that they owned the cabins long before the park appeared and did not intend to relinquish their hold without a fight. Adding to the cause of the cabin owners, Leslie Chappell, Nueces County building superintendent, owned a cabin across from the Nicaragua wreck at the 30-mile marker down-island. [35] Chappell's cabin became a companion in the case, with some arguing that it appeared after defined park boundaries and therefore deserved even less support from the Park Service.

By summer 1972 environmentalists added another argument. Because the cabins had no plumbing, they were a potential health hazard. A special study by the Park Service followed, but they detected no unusually high levels of coliform. [36] As the battle raged in local newspapers, Superintendent McLaughlin requested that the Secretary of the Interior provide a judgement. The National Park Service officially declared its position to allow all special permits to expire. With the position stated, McLaughlin sent letters to all cabin owners stating the new position. As a follow-through measure, he instructed the Laguna Madre District Ranger to begin to clear off all islands. The ranger prepared detailed files with photographs on each island. One by one owners of the cabins removed them or the ranger burned them. The Chappell Cabin immediately became the property of the Park Service and was destroyed. By 1975 all permits expired, with the last 90-day grace period ending on April 1, 1976. At last, the spoil island cabins within the park were gone. [37]

|

| Figure 21. Typical Spoil Island Cabin. Photo courtesy PAIS Archives. |

New Headquarters Building

The 1974 Master Plan recognized a number of management issues that troubled Padre Island administrators, including the restrictive size of the National Seashore headquarters building in Flour Bluff. In March 1965 when the headquarters building opened, the 2,715 square feet seemed generous for the small staff and new park. By the early 1970s, however, the building at 1001 Island Drive no longer met the demands of the park staff and a visiting public.

Almost a year before the lease on 1001 Island Drive (10025 South Padre Island Drive) expired, the General Services Administration began to negotiate a new lease. Despite repeated attempts to reach an agreement for expansion or modification to the existing building, none could be reached. General Services Administration personnel faced a dilemma of whether to move the headquarters somewhere within the Corpus Christi area or relocate to the island as originally planned in the 1960s. As the park staff and General Services Administration explored the latter idea, it became apparent that relocating to the island was impractical. The Malaquite Beach facilities suffered from the extreme environment of the island and the park lacked funds to construct a new headquarters. The General Services Administration decided the more acceptable approach was to locate or build a building in Flour Bluff that allowed direct access to visitors who might be headed toward the seashore. By midyear 1975 the General Services Administration and park administrators agreed on the remodeling of a building at 9405 South Padre Island Drive, roughly two to three blocks from the first headquarters. Architect Joe Williams and contractor Cliff Zarsky, both from Corpus Christi, directed and completed the work on the new building. W.R. Anderson of Corpus Christi became the new leaseholder.

The new building opened onto South Padre Island Drive with a small visitor and interpretive center. To the rear, offices lined the perimeter of the building with sliding glass doors facing onto a courtyard covered with skylights. The courtyard housed a number of plants, many provided by the architect from his own greenhouse. Storage rooms were at the far back with access to a partially covered parking lot. [38]

The Park Service dedicated the new headquarters on May 22, 1976, at three in the afternoon. Superintendent John Turney led the ceremonies with the mayor of Corpus Christi, Jason Luby, and Associate Regional Director Monte Fitch cutting the ribbon. [39] This building continues to serve as the headquarters.

Negotiations with Concessionaire

When the Malaquite Beach facilities finally opened in 1970, Padre Island National Seashore Company, as the sole concessionaire, offered a full complement of visitor provisions including a food and beverage service, vending machines, legal alcoholic beverages, miscellaneous merchandise, beach and camping equipment, and locker rental services. [40] The Company, operating under a 20-year agreement with the National Park Service, seemed to have an unlimited ability for profit. They, however, began to report annual losses almost immediately. In 1973 the Company announced its first profit of $7,420 showing a gross income of $167,632.24 from $160,212.03 in 1972. As was becoming an annual request, the Company still sought a waiver on its franchise fee because of an overall loss in revenue of $48,770.97. This request prompted an audit by the General Accounting Office to determine the cause of the Company's losses. [41]

Park staff seemed ambivalent about the Company's financial problems. Reports from the early 1970s indicate an awareness of the financial problems, but a growing concern over the poor maintenance and sanitation practices of the Company. By 1973, the Park Service prepared and implemented a Maintenance Agreement with the Company to ensure better practices. [42] The following year the Company again reported a loss. This time the Park Service granted some relief on the franchise fee but realized it was hardly enough to offset the Company's losses. [43] The 1975 Annual Report reflected the demise of the Padre Island National Seashore Company by stating that approval of a prospectus for a new concessionaire was expected soon from Washington. [44] In spite of the effort to seek a new concessionaire, the National Seashore Company remained in the Malaquite Beach complex until discontinued in 1979. [45]

Visitation and Law Enforcement

In 1970 National Park Service officials voiced high expectations for Padre Island National Seashore. With the Malaquite Beach facilities operable, visitation seemed sure to grow each year. For most of the 1970s, this appeared to happen. Between 1971 and 1972, almost 200,000 more visitors came to the National Seashore, virtually doubling the amount from four years before. But in 1974 and 1975, the national energy crisis reduced the number of automobiles on the highways and dropped visitation back to pre-1970 numbers. This setback was short lived. A renewed sense of confidence and relaxed fuel supplies brought an all-time high number of visitors in 1976, over 968,000. This number, however, began to drop toward the end of the decade and began a trend of steady declines throughout most of the 1980s.

Increased numbers of visitors brought new problems for the National Seashore staff. Following the riots in Yosemite National Park in July 1970, the National Park Service stressed law enforcement in all of the national parks. Some Park Service employees argued that this new emphasis came at the expense of interpretation and resource conservation programs. At the same time, few employees denied that there was a need for strong enforcement. Padre Island National Seashore, like other parks, experienced its own set of problems.

Padre Island rangers reported that hunting violations, usually during duck and geese season, were the major offense in 1970. These were minor offenses usually caused by a hunter straying into the National Seashore unaware of the boundary. [46] By 1972 rangers reported different violations, from illegal possession of drugs to excessive speeding and liquor law violations. In 1972 arrests increased four times from 27 to 107, mostly for drugs. [47] The following year law enforcement rangers implemented a new reporting system. Using the Form 10-343, Case Incident Record, rangers developed more reliable statistics than in previous years and reported in 1973 to have the most accurate to date. Once again, the number of arrests grew to 244, largely for illegal drug possession. Some rangers felt that the number may have been even larger except for an agreement between the Park Service, United States Attorney, and Magistrate. This agreement allowed park rangers to cite those in possession of small amounts of drugs rather than arresting them, beginning October 1973. [48] Over the next few years, the number of cases and incidents grew to an all-time high in 1976. Drug violations, however, slowly began to drop with only 50 reported in 1979. [49]

Implementation of Master Plan

After adoption of the Master Plan in 1974, Superintendent Jack Turney, superintendent at White Sands National Monument until December 1973, updated and submitted to Washington legislative data for a south boundary change. [50] The new plan called for an exchange of the small acreage acquired by the Park Service during its acquisition phase but now separated by larger acreage no longer under consideration. Although offered by South Padre Investment Company a year earlier, the Park Service was only now in a position to act and even then not without legislative approval. In 1975, Turney reported that the data submitted would be included in omnibus legislation during the Second Session of the 94th Congress. [51] The following year Turney reported that Congress enacted the legislation approving the land swap, but he took no administrative action. [52] By the end of the 1970s, the Southwest Region of the National Park Service and Padre Island staff continued to debate alternatives for handling the legislation and potential land swap. [53]

As the decade came to a close, the National Seashore listed progress on several other parts of the plan. When the Chevron Company decided to shut down its operation of the Permian tank on Bird Island Basin, the Park Service reinstated its right to use the road. After road repairs were completed in 1975, visitors accessed the Laguna Madre and boat docking facilities as outlined in the plan.

In January 1979 the National Seashore explored the idea of mass transit to the island as suggested in the Master Plan. Under a contract with the park, Alan M. Voorhees and Associates of Aurora, Colorado, examined a number of options for reducing vehicular use within the park. One of the options included developing a transit system to Yarborough Pass and the Mansfield Channel. The contractors believed that park visitors would use such a system but it required heavy subsidization by the Park Service. They also explored and abandoned the idea of a ferry service across the Mansfield Channel. Likewise, the planners looked at restricting four-wheel drive vehicles but stopped short of any recommendations. The consultants studied the concept of a new inland roadway to Yarborough Pass, but dropped the idea. The Voorhees report changed little at the National Seashore. [54]

New Issues in the Management of Padre Island

At the end of the 1970s, the National Seashore encountered a new issue that profoundly effected the park and its staff. During spring 1979 a blowout occurred at one of the many off-shore oil wells owned and operated by the Mexican government in the Gulf of Mexico. IXTOC I, as it became known, released its contents into the Gulf waters for three months before measures were taken to stop the flow. Because the Gulf currents flow along the Mexican border in a northwesterly direction, the park staff knew there was a strong possibility that oil would wash ashore in the park. On August 9th the effects of the oil spill became evident. Small tar balls washed onto the shore south of Big Shell Beach. Gradually, larger sheets of crude oil and pancakes or blobs appeared. [55]

Six months before IXTOC I, Myrl Brooks arrived at Padre Island as its new superintendent, from being superintendent of Voyagers National Park in Minnesota. Brooks, who had risen in the Park Service ranks as a park ranger, was not prepared for this issue. After he no longer could delay addressing the problem, Superintendent Brooks, in consultation with Chief Park Naturalist Robert Whistler, flew down the island to inspect the washed-up tar on the beach. Shortly thereafter, Brooks requested Whistler to attend the United States Coast Guard meetings that were periodically updating the public on the spill. Whistler immediately began planning for the worst situation. He requested special funding from the Regional Office for a baseline study on the beach, and contacted the United States Fish and Wildlife Service to set up a bird cleaning station at Malaquite Beach. Even the Natural Resources Office in Washington sent a staff member, Dr. Schoenfield, to observe and work with the National Seashore staff on the spill. The Coast Guard assisted the park for one week and then discontinued its work. They did, however, successfully place booms at Mansfield Channel to prevent leakage into the Laguna Madre. [56]

As the wash-up continued, park maintenance staff tried every technique possible to eliminate the tar. A road grader raked the material into raised furrows roughly one foot in length and moved it to the upper beach. These furrows tended to gradually break down and disintegrate into the sand. When the oil patches grew too frequent and large, this practice became infeasible. The National Seashore purchased a Barber Beach Rake that helped to clean up debris as well as tar balls. Eventually, most of the staff simply gave up. By late summer, storms produced high tides on the beach and the currents shifted to a southerly direction. These natural changes helped to clean the beach and shorten the life of the spill. [57]

The IXTOC I spill seriously hindered park operations. A national flurry of bad press coverage seriously reduced visitation. As a consequence, the concessionaires at Malaquite Beach went out of business. The most serious problems manifested themselves in the staff of the National Seashore. A greatly demoralized and overwhelmed staff faced the spill with little assistance, experience, and support. Robert Whistler, one of those directly involved, took a short hiatus to recover from the mental drain. In less than six months, Superintendent Myrl Brooks retired from the Park Service, in part a victim of the worst oil spill in United States history to that point. [58]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

pais/adhi/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 14-Jun-2005