|

Padre Island

An Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER SEVEN:

MANAGEMENT AND PLANNING ISSUES 1980 - 1993

Hurricane Allen

After almost 20 years of operation, the staff at Padre Island National Seashore anticipated the annual hurricane season. The chief ranger prepared and practiced a hurricane plan annually with the idea that each new season might be the one to bring a great storm to the island. From midsummer to early fall, the staff watched weather patterns in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico and monitored the path of any new tropical depressions or storms. Several hurricanes had threatened the park since its establishment, but no direct land fall had occurred within the park boundaries. In 1967 Hurricane Beaulah landed at the mouth of the Rio Grande, causing wind and water damage to the new park. In 1970 Hurricane Celia hit land north of Padre Island between Corpus Christi Bay and Port Aransas. [1] These storms demonstrated the serious and destructive nature of hurricanes without causing the Park Service to alter its development plans for the National Seashore. The course of events in the 1980 hurricane season soon changed the park's development forever.

Bill Luckens came to Padre Island in late spring of 1980 from Saguaro National Monument in Tucson, Arizona, to assume the superintendency. After years of working in various parks in the West, Padre Island was his first non-desert assignment. In June, Chief Ranger Max Hancock presented the park's updated Hurricane Plan to Luckens and the staff. Employees received assigned tasks and an overview of steps for evacuation. As the summer months unfolded, the threat of a hurricane remained constant but nothing developed. During early August, things began to change. Weather reports identified a tropical storm forming in the Caribbean. Over the next few days the storm grew in strength and intensified as it crossed the Gulf of Mexico. The Hurricane Center in Miami watched its movement and soon predicted its probable landfall along Padre Island. [2]

The National Seashore staff moved to action. Putting its Hurricane Plan into effect, the staff boarded up all the facilities on the island and at Flour Bluff, and moved all four-wheel drive vehicles to the headquarters building. Park rangers traveled the length of the park to evacuate all campers and visitors. Staff members living on the island left for San Antonio. Within a matter of hours, the park employees closed the National Seashore, leaving behind them secured entrance gates. [3]

Hurricane Allen, as it was named, developed winds of close to 180 miles per hour, making it a very powerful storm. Forecasters now predicted it to land somewhere near the Mansfield Channel at the southern end of the park. In the days and hours that passed before landing, some coastal residents left for more inland locations while others braced themselves for the onslaught of the hurricane. On August 9th Hurricane Allen landed as predicted. Fortunately, just before reaching land its winds dropped to below 120 miles per hour making it less treacherous than estimated. Nevertheless, its destruction proved serious. [4]

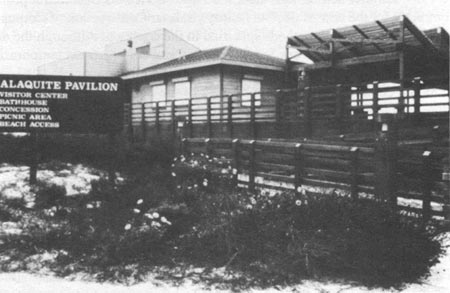

Hurricane Allen left the barrier island in a shambles. The protective foredunes fell to small hills of sand and scattered as much as 150 feet inland. Large alluvial fans spread across the grasslands down-island and many washovers left the barrier system defenseless. The storm caused serious damage to the already vulnerable Malaquite Beach facilities. The lower level campground broke into hundreds of small pieces with concrete picnic tables heaped on top and laying wherever the water left them. All the cabanas and beach resources under the Malaquite Pavilion washed away, leaving the support pillars exposed as much as five additional feet. [5] In large part, the barrier acted as it should have under such circumstances. The height of the foredunes reduced the strength of wind and flow of water before it hit the mainland. Although washovers and washouts occurred, these were typical of storm damage on barrier islands. Where human intervention left the dunes exposed and in an unnatural form, the damage was far more severe.

Most of the Malaquite Beach facilities returned to normal operations after a brief cleanup period. The foredunes gradually began to restore themselves under the natural processes of the barrier island. Damage to the Malaquite Pavilion, however, fully manifested itself several years later. In 1983 the staff reported patches of concrete falling off and determined that saltwater penetrating the building during the storm finally reached the steel supports and led to the flaking concrete. These problems, added to the existing maintenance dilemmas, required the Park Service to reconsider retaining the existing facilities and rethink recreational development on the barrier island. [6]

|

| Figure 22. Debris from Hurricane Allen. Photo courtesy PAIS Archives. |

General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan

In the aftermath of Hurricane Allen the National Park Service reevaluated the 1974 Master Plan. Within a few months, Superintendent Luckens initiated a new planning endeavor recognizing some of the issues in operating a park on a barrier island. Hurricane Allen had caused millions of dollars of damage to the Gulf Coast, being particularly unkind to structures and buildings placed in "high-hazard" zones. The Malaquite facilities located on the high-hazard foredunes required an estimated $562,000 in repairs. This estimate did not include the preexisting conditions of the pavilion caused by the corrosive salt-air and wind since its construction. Luckens and staff examined the documented and observed visitor use and travel trends between 1974 and 1981 to determine visitor demand. They discovered that visitation, as projected in the 1974 plan, was approximately twice greater than the current one million arriving annually. These factors pointed to a new philosophy for development on the barrier national seashore. [7]

As part of the new planning process, the National Seashore staff involved visitors in identifying current issues and concerns. Some of the public comments included the following: (1) need for a 24-hour ranger patrol to reduce law enforcement and resource management problems; (2) improved boat launching facilities at Bird Island Basin to reduce congestion and waiting time; (3) addition of down-island visitor use facilities; (4) management action to reduce resource damage and conflicts among visitors associated with Off Road Vehicles (ORVs). These comments and the already identified issues led to less development-oriented management for the National Seashore. An integrated set of proposals followed in the new Draft General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan released in November 1981.[8]

Superintendent Luckens and the planning team, mostly from the Denver Service Center, proposed several ways to integrate resource management, visitor use, operations, and development at least through the early 1990s. The first proposal directed the island to be managed to sustain natural processes. In other words, new facilities and visitor activities would be designed to conform to the island's natural processes rather than trying to adjust them to fit human needs. Second, the team suggested that all new development anticipate an annual visitation of approximately one million, but that the Park Service not commit itself to maintaining large permanent facilities that would accommodate more visitors. Finally, in memory of Hurricane Allen, the team stated that since hurricanes will continue to hit the Gulf Coast and potentially Padre Island, the perpetuation of the foredunes was a necessity in order to maintain the island's defenses. [9]

Natural resource management now became the priority for the National Park Service on Padre Island. The staff no longer interfered in natural processes except to correct situations of human degradation. Dunes depleted by humans or vehicles, such as those at Malaquite Beach, would be restored by planting native grasses. Other dune denudation remained until it corrected itself. If another hurricane came ashore on Padre, natural processes would restore the island to its former condition in their own time. The Park Service, however, continued its research programs in order to better understand the functions of the barrier island and island wildlife. This included the popular Kemp's ridley turtle project and protection of the nesting habitats on the spoil islands. [10]

In other areas of park management, the planning team proposed few changes. Malaquite Beach continued to be closed to vehicles while North and South Beaches could be accessed by two-wheel drive vehicles and beyond that four-wheel drive vehicles. The team suggested that interpretation programs be expanded and redesigned to inform two types of visitors. Local short-term visitors, approximately 85% of the total visitation, received basic information about the barrier island. The park offered other visitors opportunities for in-depth education on the island and special activities. The team envisioned more interpretation at Malaquite Beach, headquarters in Flour Bluff, and an expanded wayside exhibit program. Finally, park operations would be confined to a permanent headquarters in Flour Bluff with only minimal support facilities based on the island for daily use by staff. [11]

In the accompanying Development Concept Plan, park planners departed from the earlier development strategies by relocating or modifying some existing visitor facilities and limiting other visitor support facilities to that essential for safety or resource protection. The most extensive changes were proposed for Malaquite Beach. After many years of deterioration and high maintenance costs, the pavilion would be replaced within a five-year period. Planners now envisioned "less permanent," "expendable," or even "transportable" structures that housed visitor services such as information/orientation, showers, restrooms, and concessions. Park planners called for all new buildings and structures, save the beach lifeguard and first-aid station, to be located behind the foredunes on the existing paved parking area and connect to utility lines already in place. They redesigned the extensive 1,200-vehicle parking area, too large for current visitations, to provide for 100 tent and recreational vehicle camping sites. These new sites would replace those destroyed by Hurricane Allen and the surviving 40 still on the fore-island dune ridge. Planners called for the removal of all remaining camping sites on Malaquite Beach, access roads, and comfort stations. Tent camping, however, remained in the existing camping area. To restore already damaged natural resources, the Park Service reestablished the fore-island dune ridge at the pavilion and camping area. While the natural forces worked, visitors accessed the beach by way of raised boardwalks [12]

The planners identified other areas within the park for changes in addition to those at Malaquite Beach. They wanted Bird Island Basin to offer visitors a hard-surfaced boat launch ramp with disabled accessibility and ensure all existing visitor activities would be retained. In a similar vein, Yarborough Pass provided acceptable primitive campsites but the access road needed improvement. The planners arranged for wayside exhibits carrying orientation and interpretation material to be expanded at the entrance and Flour Bluff headquarters, Bird Island Basin, North Beach, Malaquite Beach, South Beach, and at the start of the four-wheel-drive area. Staff also developed a new interpretive self-guided walk with barrier-free parking constructed near Malaquite Beach for interpreting the nearby ponds and wetlands. The long-established Grasslands Nature Trail and its parking area also became disabled. [13]

The planners addressed the ranger and maintenance areas as the last part of the plan. They recommended the removal of Caffey Barracks, now almost 20 years in Park Service possession, and all additional storage buildings except for one vehicular storage building. The team suggested that all ranger functions required on the island be moved to the view tower after some modifications to the observation level for office space, storage, communications center, and restrooms. The other functions now carried out at the ranger station remained in additional rental facilities near the headquarters in Flour Bluff. Planners suggested moving off the island the employee's residences on the island, two wood-frame and two mobile homes. [14] Durable sectional mobile homes, however, soon replaced the old buildings at the same location. [15]

While the park planners sought to reduce the use of permanent buildings on Padre Island, they supported adding new buildings that fit new criteria. Mobile and flood-proof buildings that were energy efficient and accessible to all disabled persons became the model for new construction. The planners further recommended that all new buildings be located out of the 100-year floodplain or be elevated to accommodate estimated water levels. Park planners also stressed that new buildings, structures, and trails must be oriented with respect to the environment of the island including solar energy, winds, vegetation, and natural site conditions. [16]

The Park Service devoted the last part of the Development Concept Plan to evaluating visitor carrying capacity and incorporating this into four broad management zones including natural environment, historic, development, and special use subzones. As the new planning team concluded, visitor capacity at other parks is set by the size of facilities. In Padre Island National Seashore, the capacity must be determined by management policies, climate, and vehicular characteristics, except for Malaquite Beach which is set by the availability of parking. [17] The team devised management policies for the first time that put the environment and natural resources ahead of visitor accommodation. These zones were a noteworthy attempt at administering Padre Island National Seashore by emphasizing resource conservation.

In order to comply with Federal environmental regulations under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969, the park planning team completed an Environmental Assessment for the General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan. Citing the outdated approaches given in the 1974 Master Plan, the planners outlined three alternatives for development of the National Seashore. Alternative One called for removal of all major facilities as prescribed in the new Draft Concept Plan. This alternative offered the smallest-scale visitor facilities, least amount of resource changes, and smallest number of facilities on the island. Alternative Two supported the current situation in the park which followed a blending of concern for visitor facilities and resource conservation. Alternative Three proposed an upgrading and retention of visitor-use facilities that placed the visitor's experience and accommodation above the needs for resource conservation. Each of the three alternatives described by the planning team were to be evaluated against compliance with the legislative intent based on an analysis of the positive and negative aspects of each one. The final evaluation of the Environmental Assessment, however, would be formed after soliciting public comment and Federal agency approval. [18]

In late 1981, Superintendent Luckens released the three documents to the public and set three public meetings for January to discuss content. Written comments were encouraged and required by mid-February. After a series of well-attended meetings in early 1982, the Park Service forwarded the General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan to the Southwest Regional Office and onto Washington for approval. In April 1983, approximately one year later, the Park Service adopted both plans with three key proposals to be carried out over a 10- to 15-year period. First, the National Park Service continued protection of the island's natural and cultural resources. Second, park staff supported established levels and patterns of visitor use. Finally, the staff facilitated efficient park operations. [19]

Land Protection Plan

Two years later, in September 1985, the National Park Service adopted a Land Protection Plan as guidance for future park land acquisition. Superintendent Luckens and the new planning team referred back to research conducted for the General Management Plan to determine if any lands within the authorized boundary were unnecessary or inappropriate for park purposes.

Park planners once again turned to the question of the land south of Mansfield Channel and the tracts there held in abeyance since 1980 when Congress approved acquisition under Public Law 96-199. Tract Seven, still in private ownership, consisted of 262.56 acres immediately south of the Channel. This tract remained, in addition to approximately 2,000 acres south of Mansfield Channel originally designated for National Seashore acquisition. Most of the acreage was now owned by the Federal government, including 1,829.4 acres in Tract 8-103, deeded by the State of Texas in 1963, six acres in Tract 8-104, and 12 acres in Tract 8-105. The latter two were purchased during the land acquisition program of the 1960s but were separated from the main park by the controversial Tract Seven. Public Law 96-199 allowed the National Park Service to delete all of Tract Eight, returning the State of Texas land and either exchanging or disposing of the other 18 acres.

As of 1985, the National Park Service had taken no action on Public Law 96-199. Hurricane Allen, a new park superintendent, and the overriding problems of providing visitor services in the park precluded following through with the law. The new Land Protection Plan and adopted General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan provided the management structure to complete the task. After determining that the disposal of land was consistent with the Coastal Barrier Resources Act of 1982, the Park Service proceeded. This Act restricted the use of indirect or direct Federal expenditures for economic growth or development on the barrier system along the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. These restrictions were imposed to reduce loss of life, wasteful expenditures, and damage to natural resources along the coastal barriers resulting from development. [20]

The National Park Service now seemed determined to move ahead in the disposal of land by eliminating the last 262 acres in Tract Seven from the authorized land acquisition program. The General Management Plan/Develop Concept Plan listed four reasons for its removal: (1) development of recreational facilities south of Mansfield Channel was not feasible, (2) the National Park Service now had guidelines that discouraged development in areas subject to flooding, wave erosion, or overwash, (3) expense of development and operational costs, and (4) failure to gain significant resource management benefits. In the fall of 1985, the Park Service posted its intention to remove this acreage from the proposed park in the Federal Register, as approved in earlier plans. [21]

This deletion of acreage south of Mansfield Channel ended the long controversy over providing National Seashore facilities to residents of South Texas. The court battles of the late 1960s that sided in favor of the property owners left the southern end of the proposed park vulnerable to extensive development. By the late 1970s when South Padre Island Investment Corporation offered the acreage to the Park Service, it became obvious that the corporation's original intent to develop the land seemed unlikely. After the passage of the Coastal Barrier Resources Act in 1982, development was virtually impossible. For the same reasons that precluded private development, park use seemed unlikely, making the decision by the National Park Service to eliminate Tract Seven in 1983 long overdue.

One tract of land within the park boundaries remained in question in 1985. Tract 13 consisted of slightly more than 78 acres with surface rights owned by the Willacy County Navigation district, northwest of the Mansfield Channel. The State of Texas still owned all minerals on the tract. These mudflats, often inundated by high tides, remained largely undesirable for park use. Nevertheless, the land possessed strong natural resource values where it provided a feeding ground for the endangered Bald eagles and Peregrine falcons. In reconsideration of the tract in 1985, park planners looked at the acreage from a different vantage point. Since the National Seashore's staff now gave natural resources prominent consideration, Tract 13 fit neatly into the objectives of the park. Park planners discussed several alternatives for including the land in the National Seashore. Federal regulations did not require park managers to be contacted prior to mineral extraction on the acreage. If a cooperative agreement were in place, the National Park Service must provide input but may not prohibit incompatible uses. If the Park Service acquired a scenic easement, the easement might preclude some development, but not mineral extraction. As a final alternative, the National Park Service acquired the land with full-fee interest directly from the Navigation District as allowed by Texas Civil Statutes, Article 6077t, Section 7. Park Service ownership gave the park the authority to enforce mineral management uniformly throughout the park and immediately adjacent areas. The Land Protection Plan concluded with the recommendation of the planners: Tract 13 should be acquired with fee interest and, if unsuccessful, a cooperative agreement should be negotiated with the Navigation District for short-term protection. [22] When the National Park Service fulfilled this recommendation, it completed the land acquisition program begun almost 20 years earlier.

Malaquite Beach Pavilion

By January 1986 the Malaquite Beach Pavilion could no longer withstand daily use without being a safety hazard. For more than three years, sections of concrete fell from the pavilion much as it had prior to the mid-1970s overhaul and patching. In the spring of 1983 Superintendent Luckens requested an architectural and engineering study to determine the financial feasibility of repairing the building or building a new one. [23] The 1984 General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan, approved a few months later, more directly stated that the Malaquite Pavilion should be replaced within five years.

Park staff began a special "scaling" program the following year to monitor the deterioration of the concrete and its removal. On a bimonthly basis, staff maintained the frequency of scaling and removal of concrete from the pavilion on the National Seashore's computer. As sections became worse, the staff fenced off areas like that underneath the boardwalk where visitor safety became a major concern. [24]

In the meantime, the Park Service planned and designed a new visitor facility to replace the existing Malaquite Pavilion. They secured funds from the Visitor Facility Fund of the National Park Foundation to begin construction in the summer of 1986. [25] The Park Service appropriated $800,000. Harris Sharp and Associates, an architectural and engineering firm from Corpus Christi, prepared a new design under contract to Bechtel, Inc. [26] Bechtel, Inc., initially provided management representation for the National Park Foundation, but by mid-1985 the Denver Service Center took over the program and solicited bids for the new facility. By June, preparations included removing two fire hydrants and capping water lines. [27]

All of the bids received for the Malaquite Beach replacement exceeded the amount appropriated. The Denver Service Center, now leading the new development, revised the drawings and specifications to follow United States government procurement regulations during late summer and early fall 1986 and, instead of beginning construction, solicited bids once again. A new funding package followed that allowed the appropriation to be split between Fiscal Years 1985 and 1986. The new construction bids arrived over budget. A third revision to the design followed with a final solicitation of bids. On December 22, 1986, Park staff opened the most recent set of bids and announced a low bidder. During the next month, National Seashore staff issued a contract but delayed the "notice to proceed" until approval of bonding for the construction company arrived in late spring. Shortly afterwards, the Denver Service Center proceeded with plans to remove the old Malaquite Pavilion by developing specifications and securing funds. [28]

Park staff worked around the closed Malaquite Pavilion during the summer 1986 and 1987 visitor seasons by importing temporary buildings, one for a Visitor Center and interpretive information and another for concessions. The concessioner, now left with no facilities because of the pavilion closure, proved especially problematic. After only a few days of operating out of the temporary building, the concessioner closed down. The park staff then introduced a small vending operation, but after two burglaries, these closed as well. [29]

As the 1987 summer season unfolded, the Park Service encountered a problem with the construction contractor for the new Malaquite facility. Salazar Construction of Corpus Christi failed to provide the data of all items and methods specified in the contract. Although the delay received some negative media coverage, the Park Service and Salazar management temporarily reconciled their differences and construction on the new building began on October 26, 1987. [30]

In July 1989 the contractor turned over Phase I of the new Malaquite Visitor Facility to the National Seashore staff and Superintendent John Hunter. Hunter, who replaced Bill Luckens after his retirement in 1988, came to Padre with years of experience as Superintendent of Bandelier National Monument. He quickly picked up the development activities as a priority and reported the following year about the difficulty of working with the contractor, lack of an adequate contract to cover some important parts of the new building, and inadequacy of funding for the facility. Hunter devoted a great deal of time to the completion of the new building and raising funds in order to complete the work. [31] In order to stay on schedule, the National Seashore's own maintenance crew took over some of the final tasks for Buildings 632, 633, and 634. Crews sanded and varnished floors, reset screws, sealed the deck, and insulated and sealed the subfloor of the facility. [32]

When the Visitor Facility opened in mid-July, Phase II, including a shade structure over the deck and deck skirting, remained to be done and funded. Superintendent Hunter seemed troubled by the inadequacies of the Seashore's facilities. Although a new visitor facility greeted the public, programmed park management facilities and complete visitor facilities lacked funding. [33] In November 1990, Hunter announced additional funding of $335,000 for completion of the Visitor Center. The park staff, however, dropped the proposed shade structure over the deck when the park secured no funding. [34]

|

| Figure 23. Visitor Center. Photo courtesy PAIS Archives [843]. |

Concessions at Malaquite Beach essentially ended after the disastrous years of IXTOC I and Hurricane Allen. In 1985, National Seashore staff arranged a new contract with American Funtier, Inc. [35] This company, owned by Dr. Paul Kennedy of Corpus Christi, sold out to Forever Resorts of Phoenix in 1989 before the facility reopened. It again reorganized as Padre Island Park Company with new staff and accommodations. [36]

In 1992 the National Seashore staff began to revise the Development Concept Plan, now almost ten years old. New planners again mentioned the problem of the Malaquite Beach facilities. The new visitor center lacked audiovisual and storage space. Seashore visitors who used the old parking area needed a clear direction to the main entrance of the facility and often walked over the dunes rather than using the access provided. The planners identified the late-1960s view tower as unsound and closed to visitors. They also mentioned that the construction of the new visitor facility created a design problem leaving the old view tower "obtrusive and anomalous." [37]

After 30 years of planning for the National Seashore, the National Park Service faced many more issues in planning for the park. The Malaquite grouping remained the only visitor facilities on the island for the foreseeable future. Despite efforts to the contrary, park staff faced insufficient building specifications and troublesome contractors. The overriding issue still seemed to be the lack of funding to complete facilities as intended. Unfortunately, park managers continue to face these same problems.

Law Enforcement Issues

The National Seashore faced a number of new law enforcement issues at the onset of the 1980s. In addition to the possession of drugs, park rangers met increasing numbers of illegal aliens using the island as a point of entry into the United States. By 1985, park officials agreed to participate in a cooperative program with the Border Patrol and Customs called "Operation Alliance." This cooperation resulted in seizure of almost 900 pounds of marijuana, assistance in seizing another 400 pounds, and the apprehension of 113 illegal aliens in one year. [38]

By the early 1990s park rangers announced a new drug interdiction program. This aggressive effort included trained canine inspection and special four-wheel vehicles. Park officials reported a decrease from five to one drug trafficking case in the first year of operation in 1992. Park rangers also expanded the number of cooperative agreements by adding Kleberg and Kenedy Counties in 1992 to an existing agreement with Nueces County. These agreements allowed park rangers to issue state violation notices when Federal law does not cover a specific violation. Park officials believe that this cooperation improved relations with the three counties crossing the National Seashore by bringing in local revenue. [39]

The most troublesome law enforcement issue occurred in 1983 at the height of the tourist season. On the afternoon of July 23, 1983, Park Rangers Larry Couser and James Copeland stopped an automobile driven by John Landry on North Beach. The rangers intended to stop two teenage females from hanging onto the side of the vehicle. After a few minutes of conversation with Landry, the rangers noted the smell of alcohol and suspected that all the occupants were using drugs. A brief investigation uncovered marijuana, liquor, and drug paraphernalia. Following procedure, the rangers told Landry to park his vehicle and remain there until they returned from delivering the two girls to the Ranger Station. When they returned, Landry had left the beach and park. Several hours later, the Corpus Christi police arrested Landry after he hit a motorcyclist. Although Landry was arrested at the scene, the injured driver on the motorcycle, Randy William Crider, lost an arm and leg from the accident. Mr. Crider sued the Federal government because the rangers had not arrested Landry earlier in the day and thus prevented the accident. A local court faulted the park rangers, but on October 10, 1989, a subsequent court hearing at the district level reversed the lower decision. [40] The Crider case haunted Padre Island staff for many years and is still used as a landmark case in law enforcement training for national parks.

Hazardous Substances and Waste

As early as the 1970s, National Seashore staff recognized the increasing presence of 30- and 55-gallon drums washing ashore. The strong Gulf of Mexico currents that converged near Big Shell Beach deposited these drums from North and South Beach down to the southern end of the park. Some of these carried labels noting hazardous substances, others were distorted indicating some internal combustion occurred. Most of the drums derived from offshore oil drilling platforms, crew boats, and cargo ships, known to be working with toxic materials. The Park Service staff became concerned when materials from within the drums leaked. Bullet holes in the drums suggested that park visitors used these for target practices and sometimes as windbreaks around campfires. [41]

The park staff soon developed its own "Beach Cleaning Plan" for handling the hazardous drums. Barrels washing ashore on North and South Beach received top priority and a two-hour response for removal. When the beaches closed, rangers checked the beaches at least once a week and removed any barrels within one week. The majority of the beach, that area below South Beach and accessible only by four-wheel-drive vehicles, was not covered in the plan. At the same time, the plan did not specify protective equipment or clothing, except steel-toed boots and gloves. [42] The plan, while a significant step forward, failed to recognize and highlight the seriousness of managing a hazardous waste product.

A new plan went into effect in 1981 receiving partial funding of $10,000 from the Park Restoration and Improvement Program. National Seashore employees recovered 170 55-gallon drums from the four-wheel-drive sign on South Beach to Mansfield Channel. With two days of free use of a Rolligon vehicle, provided by a pipeline firm then laying natural gas pipeline across the park, park staff recovered the drums and placed them in a designated area near the sewer lagoon storage just west of Malaquite Beach. They crushed and disposed of all barrels without hazardous substances. National Seashore officials could not dispose of the last 30 drums until their contents were tested and reported. A local environmental firm tested the contents free of charge while a local vacuum service removed the contents. [43] The National Seashore later purchased its own all-terrain amphibious tractor or Rolligon for $57,870 from the Rolligon Corporation as a means for collecting the drums from the beach and continuing the collection program. [44]

In the following three years, park employees recovered and counted an increasing number of drums washed ashore. In August 1982, employees recorded 40 drums on the four-wheel drive beach. During the same month in 1983, they counted 60 drums and recovered 80 in August 1984. An additional 26 drums washed ashore in the northern parts of the park during these last two years. When the Park Service calculated its total finds over the early 1980s, they estimated that approximately 150 drums, or one every two days, washed onto the beaches of the National Seashore. Park officials reported that of those recovered 30-50% contained substances and most were in some stage of deterioration. Although testing of enclosed substances produced no pesticides or PCBs, park officials found a variety of inflammable liquids and harmful materials. In 1985 and 1986 the drums continued to wash ashore with 237 appearing during the first year and 110 in the latter. [45]

National Park Service officials soon were forced to address the issue of hazardous waste directly. In a cooperative effort with the United States Coast Guard and Environmental Protection Agency, the Park Service developed a program to sample, analyze, and dispose of the drums as they were sighted. Largely using Superfund cleanup money from the Environmental Protection Agency, National Seashore staff reported drums to the Coast Guard who in turn contacted its contractor to collect the drum. All collected drums were held temporarily in the park near the sewer lagoon until disposed. [46] In 1985 the National Seashore continued to hold 60 hazardous waste drums as it awaited approval for their removal to South Carolina. [47]

Cooperative activities between the various Federal entities remained active through Fiscal Year 1987 when the Environmental Protection Agency stated that it no longer regarded the drums an "emergency" worthy of funding under the Superfund. Likewise, the Coast Guard and Environmental Protection Agency believed all drums washed ashore were the problem of the responsible land agency, i.e., National Park Service. To cover the new expenses, the Padre Island staff requested $250,000 in Fiscal Year 1988 to assume responsibility for the program. In the next two fiscal years, the Environmental Protection Agency threatened to discontinue funding the drum removal, but after interference from Department of the Interior officials, the program continued through 1990. Park Service personnel discontinued the program in recent years.

Palo Alto National Battlefield Development

For many years after designation, Padre Island National Seashore represented the easternmost park unit in Southwest Region of the National Park Service. It was also the most developed park with any connection to South Texas and the Rio Grande Valley. After Yellowstone National Park Superintendent Roger Toll's visit to South Texas in 1933, he suggested that Padre Island be joined with Rabb's Palm Grove, now called the Sabal Palm Grove, and the battlefields of Resaca de la Palma and Palo Alto from the Mexican-American War of 1846. [48] This idea never attracted the attention of the National Park Service. Instead, the Audubon Society purchased the Palm Grove and the battlefields received nominal historical attention as the only representation of the Mexican-American War.

More than 40 years after Toll's visit, the United States Congress officially recognized the Palo Alto battlefield as Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site in 1978.. Local enthusiasts finally won the recognition they had long struggled to receive. Southwest Region officials soon set up an office and placed staff in the vicinity of the battlefield. Bob Amberger was appointed as superintendent. Within a few years, however, it became clear that Congress had no intention of furthering the interpretation or purchase of the battlefields. The Park Service dispersed the staff and chose to send all equipment and collections to Padre Island National Seashore. Shortly afterwards, the Regional Office assigned Padre's chief ranger, Max Hancock, to be "Acting Superintendent" of Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site. This status required trips, record keeping, and reports to the regional office. Harry O'Bryant, the chief of maintenance at Padre Island, later served as acting superintendent. [49]

The South Texas supporters of Palo Alto continued through the 1980s to seek a clear and committed presence for the National Park Service. In 1991, the United States House of Representatives passed HR 1642 and the Senate concurred on June 4, 1992. President George Bush signed Public Law 102-304 establishing Palo Alto Battlefield National Historic Site on June 23, 1992. [50] In response, the Park Service assigned Tom Carroll of the Southwest Region to be the superintendent. [51] Although most of the collection for Palo Alto remained with Padre Island National Seashore in 1993, plans are underway for its transfer to the new park when it completes acquisition and development.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

pais/adhi/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 14-Jun-2005