|

Pipestone National Monument Minnesota |

|

NPS photo | |

The story of this stone and the pipes made from it may span 2,000 years of Plains Indian life. Inseparable from the traditions that structured daily routine and honored the spirit world, pipes figured prominently in the ways of the village and in dealings between tribes. The story parallels that of a culture in transition: the evolution of the pipes influenced—and was influenced by—their makers' association with explorers, traders, soldiers, and settlers.

At an ancient time the Great Spirit in the form of a large bird, stood upon the wall of rock and called all the tribes around him, and breaking out a piece of the red stone formed it into a pipe and smoked it, the smoke rolling over the whole multitude. He then told his red children that this red stone was their flesh, that they were made from it, that they must all smoke to him through it, that they must use it for nothing but pipes: and as it belonged alike to all the tribes, the ground was sacred, and no weapons must be used or brought upon it.

—Sioux account of the origin of the pipestone, as recorded by George Catlin, 1836.

Across the Great Plains stories of the pipestone differ from Sioux to Crow from Blackfoot to Pawnee. These variations indicate the geographical extent to which the red stone and pipes were used and traded. The reverence with which the stories are passed down through generations is testimony to their importance.

Stone pipes were long known among the Indians of North America; 2,000-year-old specimens have been found at Mound City in today's Ohio. Carvers prized this durable yet relatively soft stone that ranged in color from mottled pink to brick red. This location came to be the preferred source of pipestone among Plains tribes. By about 1700 Dakota Sioux controlled the quarries and distributed stone only through trade.

Ceremonial smoking—rallying forces for warfare, trading goods and hostages, ritual dancing, and medicinal healings—marked the activities of the Plains people. They stored bowls, stems, and tobacco in animal-skin pouches or in bundles with other sacred objects. Valued possessions, ornamental pipes were often buried with the dead.

There were many variations in pipe designs. By the time George Catlin arrived here in 1836 the simple tubes of earlier times had evolved into elbow and disk forms and elaborate animal and human effigies. Pawnee and Sioux were master effigy carvers. A popular pipe shape was the T-shaped calumet. Calumets became widely known as peace pipes because they were the pipes that non-Indians encountered at treaty ceremonies.

As the United States expanded west in the 1800s pipes found their way into non-Indian societies through trade. increasing contact between pioneers and Indians inspired new subject matter. Some effigies honored politicians and explorers; some caricatures were far from flattering. Pipes became a source of income for their makers, significant beyond religious uses. To protect their source, the Yankton Sioux secured free and unrestricted access by an 1858 treaty. Even as the quarry became increasingly lucrative, American settlement threatened to consume the square-mile reservation. Outsiders were digging new pits and extracting the sacred stone. In 1928 the Yankton, now resettled on a reservation 150 miles away, were awarded a judicial settlement from the federal government that ended their claim to the quarries. In 1937 Congress established Pipestone National Monument to provide traditional quarrying for Indians.

Today pipe carvings are appreciated as artworks as well as for ceremonial use. Once again, as commanded by the spirit bird in the Sioux story of its creation, the pipestone here is quarried by any American Indian enrolled in a tribe recognized by the U.S. government. An age-old tradition continues in the modern world, ever changing yet rooted in the past.

Carving Pipes From Stone

The work of American Indian pipecarvers takes many forms. Since the mid-1800s the inverted T-shaped calumet has been the shape most recognizable as Plains Indian work. Metal tools acquired from traders enabled more detailed carving, but even in highly ornate effigy pipes the basic calumet shape is distinct.

Today carvers use power saws and drills for speed tools are more sophisticated, the process is similar to traditional methods when carving tools were made of stone and wood.

Carving the Bowl

Using a sharpened rock the carver outlines the bowl on a six-inch

rectangle of pipestone.

1 Excess stone is cut away. The relatively soft pipestone yields to a flint saw as the carver forms the rough bowl.

2 At this stage the carver rounds the edges by scraping the bowl against stone—perhaps using the harder quartzite removed during quarrying.

3 The shape is refined by filing. Carvers sometimes postpone filing until after the drilling because the process of boring can split the stone.

4 The bowl is secured to prevent movement as the stem hole is drilled through the longer leg of the inverted T. A connecting shaft to hold tobacco is bored perpendicular to the stem hole.

The drill shown here is wooden with a flint bit and leather thong. In 1841 George Catlin described a drilling process whereby the carver rolled a sharpened stick between his hands. Sand and water poured in the hole intensified the abrasive action of the point.

After drilling, the bowl might be left plain or decorated by carving it into a human or animal effigy or by inlaying bands of metal.

5 Finally the pipe is polished with a sand rubbing, then buffed to a gloss.

Digging the Pipestone

Quarrying usually takes place in late summer and fall. Earlier water

from snow melt and rain collects in the pits. Mid-summer temperatures

prevent activity, as quarrying is done with handtools and requires hard

physical labor.

Quarriers first shovel away the soil. Next they break up the top layer of hard quartzite with a sledge hammer and wedge, being careful not to damage the soft pipestone (catlinite) beneath. Because the pipestone bed slopes downward to the east, quarriers must dig through an increasingly thick layer of quartzite to reach new pipestone. Beneath the quartzite are one- to three-inch sheets of catlinite. Quarriers lift the sheets from the pits, then cut them into smaller blocks from which pipes are carved.

Quarrying is accomplished with respect for the Earth. American Indians traditionally leave offerings of food and tobacco beside the Three Maidens boulders in return for this land's gift of stone.

Making the Pipe Stem

Stems are hewn from branches of ash or other hardwood. After rough

shaping the branch is split lengthwise. The soft pith is scraped from

the center of both halves, creating a narrow shaft. The halves are

rejoined and secured with a sap glue and cord.

Alternatively, a heated wire is run through the core of a sumac branch to burn out the pith, eliminating the need to split the stem.

Plains women traditionally dressed the stem by wrapping porcupine quills around part of its length. Paint, carvings, feathers, beads, and animal heads adorned the stem and signified the pipe's ceremonial role.

Exploring Pipestone

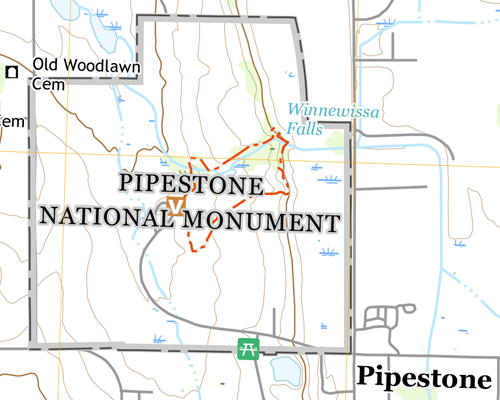

(click for larger map) |

Getting Here Pipestone National Monument is in southwestern Minnesota, just north of the city of Pipestone. Follow signs from U.S. 75, Minn. 23, or Minn. 30.

When to Visit The park is open daily, except Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1. Hours are 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., with longer hours in summer.

Things to Do Begin at the visitor center for information, exhibits, and a film. The visitor center museum and the Upper Midwest Indian Cultural Center feature publications, pipestone pipes, and artifacts. The Upper Midwest Indian Cultural Center sponsors demonstrations of pipemaking by American Indians using stone from this quarry, April into October.

Circle Trail The ¾-mile Circle Trail begins at the visitor center (ask about a trail guide). Along the trail you will see a tallgrass prairie, pipestone quarries and Winnewissa Falls. The grounds are still used by American Indians for cultural and religious activities. Note: Removing pipestone is prohibited by federal law, except by permit.

Accessibility The visitor center and paved trail are accessible to visitors in wheelchairs.

For Your Safety Do not let an accident spoil your visit. • Stay on the hard-surfaced trails. • Do not climb into the quarry pits. • Watch your footing; trail surfaces may be uneven. The entrance stairs to the exhibit quarry are slippery when wet.

Source: NPS Brochure (2012)

|

Establishment Pipestone National Monument — August 25, 1937 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A History of Pipestone National Monument, Minnesota (Robert A. Murray, 1965)

Acoustic Monitoring Report: Pipestone National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NRSS/NRTR— 2014/879 (Misty D. Nelson, June 2014)

An Archeological Inventory And Overview Of Pipestone National Monument, Minnesota Midwest Archeological Center Occasional Studies Series No. 34 (Douglas D. Scott, Thomas D. Thiessen, Jeffrey J. Richner and Scott Stadler, 2006)

Aquatic Invertebrate Monitoring at Pipestone National Monument: 2005-2007 Trend Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2009/241 (David E. Bowles, September 2009)

Bird Community Monitoring at Pipestone National Monument, Minnesota: 2009 Status Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/HTLN/NRDS—2010/045 (David G. Peitz, April 2010)

Bird Community Monitoring at Pipestone National Monument, Minnesota: Status Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR—2014/854 (David G. Peitz, March 2014)

Creek and Quarry Water Quality at Pipestone National Monument and Pilot Study of Pathogen Detection Methods in Waterfall Mist at Winnewissa Falls, Pipestone, Minnesota, 2018-19 U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2022-5122 (Aliesha L. Krall, Kerensa A. King, Victoria G. Christensen, Joel P. Stokdyk, Barbara C. Scudder Eikenberry and S.A. Stevenson, 2023)

Draft General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Pipestone National Monument (December 2006)

Final General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Pipestone National Monument (February 2008)

Fish Community Monitoring at Pipestone National Monument: 2001-2008 Trend Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2010/366 (Hope R. Dodd, Lloyd W. Morrison and David G. Peitz, August 2010)

Fish Community Monitoring at Pipestone National Monument: 2001-2014 Trend Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/HTLN/NRR—2015/1066 (Hope R. Dodd, David G. Peitz, J. Tyler Cribbs, Matthew D. Wagner, Ryan Johnston, Allen DeGoei, Kjetil Henderson, Darrel Mecham, Matthew Perrion, Benjamin Schall, Scott Sabo, Shawn Cole, Brett Miller and Brian D. S. Graeb, October 2015)

Foundation Document, Pipestone National Monument, Minnesota (December 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Pipestone National Monument, Minnesota (January 2018)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Pipestone National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2017/1512 (J.P. Graham, September 2017)

Invasive Exotic Plant Monitoring at Pipestone National Monument: Year 1 (2006) NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2007/015 (Craig C. Young, Jennifer L. Haack, J. Tyler Cribbs, Karola E. Mlekush and Holly J. Etheridge, March 2007)

Junior Ranger Activity Book: Pipestone National Monument (Date Unknown)

Managing the Sacred and the Secular: An Administrative History of Pipestone National Monument (HTML edition) (Hal K. Rothman and Daniel J. Holder, September 10, 1992)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Pipestone National Monument (David Arbogast, April 13, 1976)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Pipestone National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/PIPE/NRR-2016/1106 (David S. Jones, Roy Cook, John Sovell, Christopher Herron, Jay Benner, Karin Decker, Steven Sherman, Andrew Beavers, Johannes Beebee and David Weinzimmer, January 2016)

Pipestone: The Origin and Development of a National Monument (William P. Corbett, extract from Minnesota History, Vol. 47 No. 3, Fall 1980)

Plant Community Monitoring Trend Report, Pipestone National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/HTLN/NRTR-2007/029 (Kevin James and Mike DeBacker, May 2007)

The Blood of the People: Historic Resource Study, Pipestone National Monument, Minnesota (Theodore Catton and Diana L. Krahe, 2016)

The Pipestone Quarry and the Indians (Theodore L. Nydahl, extract from Minnesota History, Vol. 31 No. 4, December 1950)

The Red Pipestone Quarry: The Yanktons Defend a Sacred Tradition, 1858-1929 (William P. Corbett, extract from South Dakota History, Vol. 8 No. 2, 1978, ©South Dakota State Historical Society)

The Resource Report (Newsletter of the Pipestone National Monument Resource Management Division): Winter/Spring 2009

Vegetation Classification and Mapping of Pipestone National Monument, Minnesota: Project Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/PIPE/NRR—2014/802 (David D. Diamond, Lee F. Elliott, Michael D. DeBacker, Kevin M. James, Dyanna L. Pursell and Alicia Struckhoff, April 2014)

pipe/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025