|

Prince William Forest Park Virginia |

|

NPS photo | |

"You are the vanguard of that new spirit."

—President Roosevelt to the CCC men, 1933

The story of Prince William Forest Park begins with President Franklin D. Roosevelt's nationwide effort aimed at fighting the ravages of the Great Depression. People were unemployed, hungry, hopeless. In 1933 Roosevelt created a new kind of park, the Recreational Demonstration Area (RDA) to reuse marginal, overworked land.

The parks would be built by the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), a program to reduce unemployment and teach job skills. Over 2,000 CCC enrollees came to work on this land along the Chopawamsic and Quantico creeks, creating Chopawamsic RDA—today's Prince William Forest Park. Chopawamsic RDA was a model for the entire nation, one of 46 such land-use projects. It was to be a new type of camp, where low-income, inner-city children and families could get away and experience the great outdoors. Planners hoped the camp experience would build "a crop of sturdy citizens" inspired by "a close communication with nature."

The first CCC-built cabin camps were ready in the summer of 1936. There were camps for boys, girls, and mothers and tots. Each camp housed up to 200, who stayed for two to three weeks. Charity-funded groups and social agencies from metropolitan areas sponsored and ran the camps. Chopawamsic was the first southern RDA to welcome inner-city children, but the camps were segregated—boys and girls, black and white. You can see traces of those segregated days by the separate entrances to Camps 1 and 4 (black camps) and Camps 2, 3, and 5 (white camps).

That first summer over 2,000 city children learned to swim, listen for animal noises, tell scary stories at night, and wonder at nature. Today, maybe more than ever, people need to get away and experience the great outdoors. You can refresh your spirit here. Picnic, hike, fish, explore. Laugh with friends and family. Welcome to Prince William Forest Park.

"I'm looking forward most to getting healthy."

These were the words of a 9-year-old girl when asked about attending camp. Beginning in 1936 Chopawamsic RDA housed hundreds of inner-city children each summer day. Camp gave them good meals, exercise, and a chance to delight in nature. Children sometimes arrived at camp malnourished and suffering from little medical attention. Each camp had a dietician, an infirmary, and a nurse who checked the children regularly, adding eggnog to their diets if they needed to gain weight.

A HIKE THROUGH HISTORY

Civilian Conservation Corps

The first of 2,000 CCC workers arrived at Chopawamsic in 1935. They

milled timber for buildings and crushed local stone for roadways. By

1941 they had built bridges, dams, roads, and lakes. But they were most

proud of the five cabin camps. They built the cabins in a distinctive

rustic architectural style: handmade shingles, roughhewn, waney-edged

siding (not squared-off), exposed beams, and stone fireplaces—all

meant to inspire a pioneer spirit in the children who stayed there.

Spies in the Woods

Guard towers? Patrol dogs? Barbed wire? During World War II the sound of

gunfire on shooting ranges replaced children's laughter as the family

camps closed for three years, and the park became a top-secret

paramilitary installation.

Future spies stayed in the cabin camps, where the Office of Strategic Services, (OSS, forerunner to the CIA) taught men how to handle weapons and explosives, gather intelligence, forge documents, send and receive secret messages, and practice spying in nearby towns. Ask how you can stay in a spy's camp.

People Before the Park

American Indians, colonists, American Revolutionary and Civil War

troops, tobacco merchants, loggers, miners—many traversed or lived

here over the centuries. In the early 1900s farms dotted the area. Towns

thrived: Hickory Ridge, where whites and blacks lived side-by-side;

Joplin, settled by people named Abel, Carter, Liming, and Williams

(local names familiar today); and Batestown, founded by free and former

enslaved African Americans.

Watch for traces of human history in this now-forested landscape: stone piles marking property corners, old fences, or gravestones in family cemeteries. These are precious reminders of our past; please protect them for future visitors.

Piedmont Forest at its Best

If you could see the park from the air, you would see the largest green

space in the Washington D.C. metropolitan area—15,000-forested

acres fringed by urban development.

But this piedmont forest ecosystem is more than just trees; within the forest are tiers of living space that support a variety of plants and animals. The forest floor, a nutrient-rich mat that includes rotting leaves and ferns, is home to tiny animals that hide in the litter. Next is the understory, with wildflowers, evergreen shrubs like mountain laurel, and young trees. Watch for songbirds flitting among the branches. Atop is the canopy, where mature oak, poplar, and other trees leaf out each spring, shading the layers below. Look for woodpeckers hunting for insects on tree trunks.

Stones, Sand, Water, and Gold?

As you explore look for changes in the landscape from west to east.

Geological forces over eons created this scenery by heating, cooling,

and shoving massive layers of rock and earth, resulting in two geologic

zones: the higher, rockier piedmont to the west and the lower, sandier

coastal plain to the east.

They meet at the "fall line," a drop in land level where streams form rapids or waterfalls as they leave the harder rocks of the piedmont and flow over the softer rocks of the coastal plain. A great place to see the fall line is along Quantico Cascades Trail.

The next time you stroll along a creek here be aware that you are amid the Quantico Creek watershed. Water from creeks, springs, and rainfall flows eastward, eventually draining into the Chesapeake Bay. The watershed within the park is protected, but remember that human activity affects the quality of water downstream.

Don't be fooled if you see specks of gold on the Cabin Branch Pyrite Mine Trail. A mine operating here from 1889 to 1920 employed about 300 workers, including children, to extract pyrite, called fool's gold, a source of sulfuric acid used in making soap, paper, and gunpowder.

Exploring Prince William Forest Park

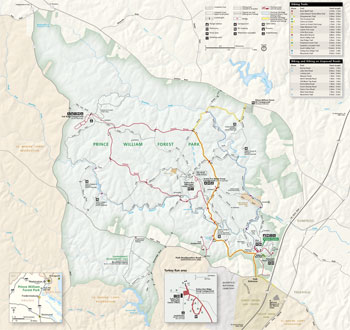

(click for larger map) |

Visitor Center Start here for information, exhibits, maps, permits, and a country store. It is open daily except Thanksgiving Day, December 25, and January 1. The park closes at dusk to all but registered campers.

Things To See and Do Whether it's a picnic, hike, fishing, or weekend in the backcountry, you'll find activities that are right for you. Contact the park or visit www.nps.gov/prwi.

Hiking/Bicycling The park has over 37 miles of hiking trails and 21 miles of biking trails. Ask for details at the visitor center.

Turkey Run Education Center This classroom facility is available year-round for organized groups planning educational or recreational activities in the park. Reservations are required.

Camping Here are some campground

highlights.

• Oak Ridge Campground. Tents and RVs (no hookups). 100 sites. Open

year-round.

• Turkey Run Ridge Group Campground. Tents only. Permits and

reservations required.

• Travel Trailer Village. RVs. Concession-operated.

• Chopawamsic Backcountry Area. Tents only; eight sites. Permits

required.

Cabin Camps Five cabin camps accommodate

groups of 60 to over 200 people. Camps have sleeping cabins, an activity

building, restrooms, and large, shared kitchens and dining halls.

• Cabin Camps 1, 2, 4, 5. Cabins for large groups; reservations

needed.

• Cabin Camp 3. Cabins for small groups or individuals; available

by reservation or first-come, first-served.

For information about campgrounds, cabins, fees, facilities, and reservations contact the park or visit www.nps.gov/prwi.

Accessibility Ask about facilities and activities. Service animals are welcome.

Safety/Regulations Please be alert. Remember, your safety is your responsibility. • Parking is prohibited in unoccupied campsites, along roads, or on the grass. • Bicycles and vehicles are not allowed on trails. • Pets must be leashed and attended. • Don't feed or approach wildlife. • Skateboards, roller skates, and fireworks are prohibited. • For firearms regulations see the park website. • All animals, plants, and other natural or historic features are protected by federal law.

Source: NPS Brochure (2011)

|

Establishment

Prince William Forest Park — June 22, 1948 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Ground Electromagnetic Survey Used to Map Sulfides and Acid Sulfate Ground Waters at the Abandoned Cabin Branch Mine, Prince William Forest Park, Northern Virginia Gold-Pyrite Belt USGS Open-File Report 00-360 (Jeff Wynn, 2000)

A New Record of Ephydatia muelleri in Prince William Forest Park (PRWI): National Capital Region Network-Inventory and Monitoring Program NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCRN/NRTR—2010/363 (Tonya M. Watts, Marian E. Norris and James M. Pieper, Jr., September 2010)

Administrative History: Prince William Forest Park (HTML edition) (Susan Cary Strickland, 1986)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Cabin Camp 1 (2011)

Ecological Variety: The Prince William Forest Park Premise (Robert H. Giles, Jr., May 1993)

"Few Know That Such A Place Exists": Land and People in the Prince William Forest Park (John Bedell, April 2004)

Foundation Document, Prince William Forest Park, Virginia (December 2013)

Foundation Document Overview, Prince William Forest Park, Virginia (January 2014)

General Management Plan, Prince William Forest Park, Virginia (February 1999)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Prince William Forest Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2009/086 (T.L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, March 2009)

Guide to Inventory and Monitoring of Amphibians on Fort A.P. Hill, Fort Belvoir, Marine Corps Base Quantico, and Prince William Forest Park, Virginia Supplement Number 1 to Amphibian Decline in the Mid-Atlantic Region: Monitoring and Management of a Sensitive Resource (Joseph C. Mitchell, September 15, 1998)

Interpretive Prospectus, Prince William Forest Park, Virginia (1989)

Junior Ranger Corps, Prince William Forest Park (2008; for reference purposes only)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Prince William Forest Park (March 2009)

Map: People and History in The Prince William Forest Park, Triangle, Virginia (John Poreda, The Louis Berger Group, Inc., 2004)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Chopawamsic RDA - Camp (1) Goodwill Historic District (Sara Amy Leach, March 25, 1988)

Chopawamsic RDA - Camp (2) Mawavi Historic District (Sara Amy Leach, March 25, 1988)

Chopawamsic RDA - Camp (3) Orenda/SP-26 Historic District (Sara Amy Leach, March 25, 1988)

Chopawamsic RDA - Camp (4) Pleasant Historic District (Sara Amy Leach, March 25, 1988)

ECW Architecture at Prince William Forest Park, 1933-42 (Sara Amy Leach, March 25, 1988)

Prince William Forest Park Historic District (Patti Kuhn and John Bedell, October 21, 2011)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Prince William Forest Park, National Capital Region NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/PRWI/NRR-2015/1051 (Brianne Walsh, Simon Costanzo, William C. Dennison, J. Patrick Campbell, Mark Lehman, Megan Nortrup, Colett Carmouche, Eric Kelley and Paul Petersen, October 2015)

Newsletter (The Oasis): Vol. 1 Issue 1 • Vol. 1 Issue 2 • Vol. 1 Issue 3 • Vol. 1 Issue 4 • Vol. 1 Issue 5 • Vol. 1 Issue 6 • Vol. 1 Issue 7 • Vol. 1 Issue 8 • Vol. 1 Issue 9 • Vol. 1 Issue 10 • Vol. 1 Issue 11 • Vol. 1 Issue 12 • Vol. 1 Issue 12a • Vol. 1 Issue 13 • Winter 2010

OSS Training Films, Prince William Forest Park

OSS Training in the National Parks and Service Abroad in World War II (John Whiteclay Chambers II, 2008)

Plan for Recognition and Reduction of Tree Hazards in Prince William Forest Park (PRWI) (Draft, undated)

Prince William Forest Park: The African American Experience (Arvilla Payne-Jackson and Sue Ann Taylor, June 2000)

Trends in Woody Forest Vegetation in Prince William Forest Park, 2006-2017 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NCRN/NRR-2023/2495 (John Paul Schmit, Elizabeth Matthews and Andrejs Brolis, February 2023)

Visitor Study: Fall 1996 — Volume I, Prince William Forest Park Visitor Services Project Report 191 (Chris Wall, June 1997)

prwi/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025