|

Rainbow Bridge National Monument Utah |

|

NPS photo | |

The World's Largest Natural Bridge

By its wonderous size, to say nothing of its majesty and mystery, Rainbow Bridge has inspired humans throughout time. Native Americans living in the region have long held the bridge sacred. From the time the bridge became known to the outside world in the early 20th century, thousands of people from around the world have visited each year. From its base to the top of the arch, it is 290 feet—nearly the height of the Statue of Liberty—and spans 275 feet across the river; the top of the arch is 42 feet thick and 33 feet wide.

How was Rainbow Bridge formed? In a word, water. The same forces that shaped Rainbow Bridge also shaped the sandstone arches and alcoves seen elsewhere on the Colorado Plateau. Water in contact with sandstone dissolves the calcium carbonate (limestone) that cements together the sand grains. Water freezing and expanding in cracks breaks away entire slabs of rock. Over millions of years a vast world of varied sculptures was created.

The rock layer from which Rainbow Bridge was formed is the relatively soft Navajo sandstone, which rests on thin layers of harder sandstone and shale of the Kayenta formation. Iron oxide and manganese have colored all of this rock various shades of pink, red, and brown. Initially, water flowing off nearby Navajo Mountain meandered across the Navajo sandstone, following the path of least resistance on its way to the Colorado River. Over time, the channel scoured from the rock became ever deeper. At the site of Rainbow Bridge, the stream happened to flow in a tight curve around a narrow fin of soft Navajo sandstone. When the stream cut down as far as the Kayenta layer, water began to force its way through the softer Navajo sandstone fin. Eventually the stream cut completely through the fin and Rainbow Bridge was created. Other forces—calcium carbonate dissolving and ice wedging away chunks of rock—shaped Rainbow Bridge into a near-perfect parabola. Over time, the same forces that shaped Rainbow Bridge will also dismantle it. Look around: throughout this region, the story of Rainbow Bridge is being played out many times over in the sunset-colored canyons of the Colorado Plateau.

Next morning early we started our toilsome return trip. The pony trail led under the arch. Along this the Ute drove our pack-mules, and as I followed him I noticed that the Navajo rode around outside. His creed bade him never pass under an arch....This great natural bridge, so recently "discovered" by white men, has for ages been known to the Indians.

—Theodore Roosevelt, after his 1913 visit,

from A Book Lover's Holiday in the Open

Tucked among the rugged, isolated canyons at the base of Navajo Mountain, Rainbow Bridge was known for centuries by the Native Americans who lived in the area. Ancestral Puebloan residents were followed much later by Paiute and Navajo groups. Several Paiute and Navajo families, in fact, still reside nearby.

By the 1800s, Rainbow Bridge was also surely seen by wandering trappers, prospectors, and cowboys. Not until 1909, though, was its existence publicized to the outside world. Two separate exploration parties—one headed by University of Utah dean, Byron Cummings, and another by government surveyor, W.B. Douglass—began searching for the legendary span. Eventually, they combined efforts. Paiute guides Nasja Begay and Jim Mike led the way, along with trader and explorer, John Wetherill. Men and horses endured heat, slickrock slopes, treacherous ledges, and sandstone mazes. Late in the afternoon of August 14, coming down what is now Bridge Canyon, the party saw Rainbow Bridge for the first time.

The next year, on May 30, 1910, President William Howard Taft created Rainbow Bridge National Monument to preserve this "extraordinary natural bridge, having an arch which is in Cummings-Douglass exploration team form and appearance much like a rainbow, and which...is of great scientific interest as an example of eccentric stream erosion." After the initial publicity, a few more adventurous souls journeyed to Rainbow Bridge. Teddy Roosevelt and Zane Grey were among those early travelers who made the arduous trek from Oljeto or Navajo Mountain to the foot of the Rainbow. Visiting Rainbow Bridge was made easier with the availability of surplus rubber rafts after World War II, although the trip still required several days floating the Colorado River plus a 7-mile hike up-canyon. By the early 1950s, people could travel by jet boat from Lees Ferry, then make the hike—a trip totaling three days!

What Teddy Roosevelt and his contemporaries witnessed—evidence of the significance of Rainbow Bridge to early and present day Native American cultures—is difficult to discern today. Since then, much archeological evidence has been lost as Lake Powell, along with thousands of visitors, arrived. The Glen Canyon Dam was authorized in 1956. By 1963, the gates on the dam closed and rising Lake Powell began to engulf the river and its side canyons. Higher water made access to Rainbow Bridge much easier, bringing thousands of visitors each year.

In 1974, Navajo tribal members who lived in the vicinity of Rainbow Bridge filed suit in U.S. District Court against the Secretary of the Interior, the Commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation, and the Director of the National Park Service. The suit was an attempt to preserve important Navajo religious sites that were being inundated by the rising waters of Lake Powell. The court ruled against the Navajo, saying that the need for water storage outweighed their concerns. In 1980, the Tenth District Court of Appeals ruled that to close Rainbow Bridge, a public site, for Navajo religious ceremonies would violate the U.S. Constitution which protects the religious freedom of all citizens.

By 1993, a National Park Service General Management Plan, involving much public input, was adopted. It offered a long-term plan for mitigating visitor impacts and preserving the resources of Rainbow Bridge National Monument. As part of the planning process, the National Park Service consulted with the five Native American nations affiliated with Rainbow Bridge: the Navajo, Hopi, San Juan Southern Paiute, Kaibab Paiute, and White Mesa Ute. Chief among their concerns was that Rainbow Bridge—a religious and sacred place—be protected and visited in a respectful manner. Additionally, the tribes expressed concerns about visitors approaching or walking under the bridge. Today, the National Park Service simply asks that you visit this site in a manner respectful of its significance to the people who have long held Rainbow Bridge sacred.

Visiting Rainbow Bridge

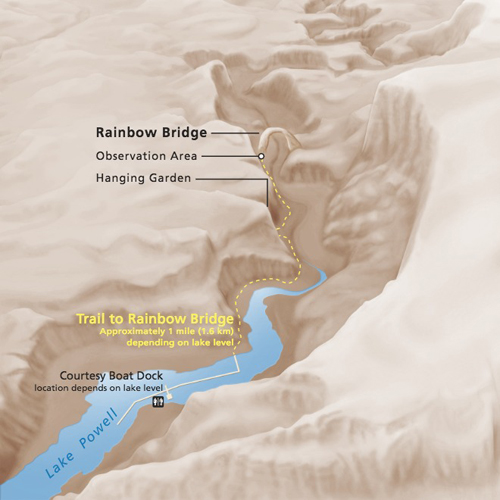

(click for larger map) |

Getting to the park

By boat: Visitors can reach Rainbow Bridge from Lake Powell by

private, rental, or tour boat. The park is about 50 miles by lake (at

least 4 hours round-trip) from Wahweap, Halls Crossing, or Bullfrog. A

path leads from the courtesy dock to a viewing area near the bridge.

Note that the trail length varies from 0.25- to 0.5-mile, depending on

the water level. On foot: Two trails that originate near Navajo

Mountain lead to Rainbow Bridge. Hikers must obtain permits before

hiking these trails. Write to: Navajo Nation, Parks and Recreation

Department, Box 9000 Window Rock, AZ 86515.

Facilities and services

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area visitor centers have exhibits and

information about Rainbow Bridge. There is a viewing area about Rainbow

Bridge viewing area 200 feet away from Rainbow Bridge. Outdoor exhibits

and park staff help to explain more about the site. To Native

American nations, Rainbow Bridge is sacred. Please respect these

longstanding beliefs. We request your voluntary compliance in not

approaching or walking under Rainbow Bridge.

Summer ranger programs and year-round restrooms are the only services available at Rainbow Bridge. Dangling Rope Marina, about 15 miles downlake near buoy 40a, has water, gas, food, supplies, and boat repair services. A ranger station near the marina has emergency medical services.

Reservations: Boat rentals, boat tours,

lodging, and camping are available through ARAMARK, Inc. You may also

write to individual locations:

• Bullfrog Resort and Marina, Box 4055, Lake Powell, UT 84533.

• Halls Crossing Resort and Marina, Box 5101, Lake Powell, UT

84533

• Hite Marina, Box 501, Lake Powell, UT 84533

• Wahweap Lodge and Marina; Box 1597, Page, AZ 86040.

Plantlife

Despite thin, poor soils and barely 7 inches of rain per year, more than

750 species of plants grow within the Glen Canyon and Rainbow Bridge

areas. Look for blackbrush, saltbush, sand sage, yucca, Mormon tea,

tumbleweed, and tamarisk. Bridge Canyon, however, is partially

shaded.and moister; sacred datura, oak, juniper, redbud, and

buffaloberry grow there.

To protect plants and soils, heed the signs and remain on the trails. Soil, kicked loose from around plants, blows away, leaving the plants teetering on slender soil pedestals. Plants die as their pedestals crumble. Help maintain healthy plants; do not wander off trails.

Safety and Regulations

Drink at least one gallon of water daily during hot weather. •

Sunlight is intense; protect yourself with sunscreen, hats, clothing.

• Wear appropriate shoes. • Snakes live in the park; be alert

and watch where you put your hands and feet. • Avoid any narrow

canyon when it is raining or rainstorms are nearby. Flash floods can

kill. • Some activities are prohibited in the park:

defacing sandstone with graffiti; removing cultural artifacts; harming

or destroying animals, plants, or other natural features; taking pets on

a trail; camping; making fires; fishing; rock climbing; throwing rocks;

swimming; diving; hunting; and carrying firearms.

Source: NPS Brochure (2000)

|

Establishment Rainbow Bridge National Monument — May 30, 1910 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Bridge Between Two Cultures: An Administrative History of Rainbow Bridge National Monument (HTML edition) Cultural Resources Selection No. 18, Intermountain Region (David Kent Sproul, 2001)

Defending the Park System: The Controversy Over Rainbow Bridge (Mark W.T. Harvey, extract from New Mexico Historical Review, Vol. 73 No. 1, 1998, ©University of New Mexico)

Devils Tower, Rainbow Bridge, and the Uphill Battle Facing Native American Religion on Public Lands (Charlton H. Bonham, extract from Minnesota Journal of Law & Inequality, Vol. 20 Issue 2, December 2002)

Did Prospectors See Rainbow Bridge Before 1909? (James H. Knipmeyer, extract from Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 27 No. 2, 1983; ©Utah State Historical Society)

Geologic Map of Rainbow Bridge National Monument, Utah (February 2024)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Rainbow Bridge National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2009/131 (J. Graham, August 2009)

Human Response to Aviation Noise: Development of Dose-Response Relationships for Backcountry Visitors, Rainbow Bridge National Monument DOT-VNTSC-NPS-17-15 (August 2017)

Junior Ranger Booklet, Rainbow Bridge National Monument (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Park Newspaper: 1991 • Summer 2005 • Spring 2006 • Summer 2006 • 2007 • 2008 • 2009 • 2010 • 2011 • 2012 • 2013 • 2014 • 2015 • 2016 • 2017

Rainbow Bridge: Circling Navajo Mountain and Explorations in the "Bad Lands" of Southern Utah and Northern Arizona (Charles L Bernheimer, 1924)

Report on Sullys Hill Park, Casa Grande Ruin; the Muir Woods, Petrified Forest, and Other National Monuments, Including List of Bird Reserves: 1915 (HTML edition) (Secretary of the Interior, 1914)

Report on Wind Cave National Park, Sullys Hill Park, Casa Grande Ruin, Muir Woods, Petrified Forest, and Other National Monuments, Including List of Bird Reserves: 1913 (HTML edition) (Secretary of the Interior, 1914)

The Battle for Rainbow Bridge (Hank Hassell, extract from Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 77 No. 4, 2009; ©Utah State Historical Society)

The Bernheimer Explorations in Forbidding Canyon (Harvey Leake and Gary Topping, extract from Utah Historical Quarterly, Vol. 55 No. 2, 1987; ©Utah State Historical Society)

The Flora of Rainbow Bridge National Monument (Walter Fertig, extract from Sego Lily: Newsletter of the Utah Native Plant Society, Vol. 33 No. 6, November 2010, ©Utah Native Plant Society)

The Great "Race" to "Discover" Rainbow Natural Bridge in 1909 (©Stephen C. Jett, extract from KIVA, Vol. 58 No. 1, 1992)

The Rainbow Bridge Case and Reclamation Projects in Reserved Areas (John B. Draper, extract from Natural Resources Journal, Vol. 14 Issue 3, Summer 1974, ©University of New Mexico School of Law)

Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area and Rainbow Bridge National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NCPN/NRR—2017/1500 (Amy Tendick, John Spence, Marion Reed, Keith Shulz, Gwen Kittel, Kass Green, Aneth Wight and Gery Wakefield, August 2017)

Visitor Study: Summer 2007 — Rainbow Bridge National Monument (Volume I) (Ye Le, Nancy C. Holmes, Alison LaDuke, Douglas Eury and Steven J. Hollenhorst, June 2008)

rabr/index.htm

Last Updated: 03-Mar-2025