|

Santa Fe National Historic Trail CO-KS-MO-NM-OK |

|

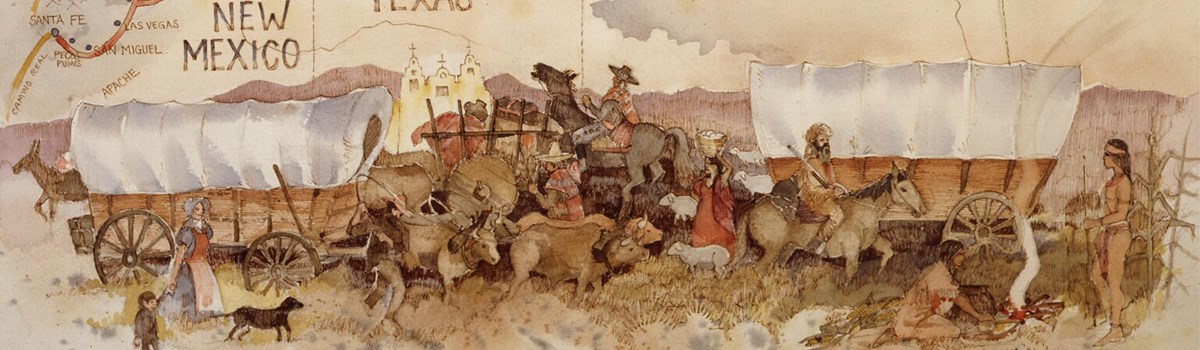

NPS photo | |

The Great Prairie Highway

The Santa Fe Trail stirs imaginations as few other historic trails can. For 60 years the Trail was one thread in a web of international trade routes. It influenced economies as far away as New York and London. Spanning 900 miles of the Great Plains between the United States (Missouri) and Mexico (Santa Fe), it brought together a cultural mosaic of individuals who cooperated—and at times clashed. In the process, the rich and varied cultures of Great Plains Indian peoples caught in the middle were changed forever. Soldiers used the Trail during the 1840s border disputes between the Republic of Texas and Mexico, 1846-1848 Mexican-American Wa and America's Civil War, and troop policed conflicts between traders and Indian tribes. With the traders and military freighters tramped a curious company of gold-seekers, emigrants, adventurers, mountain men, hunters, American Indians, guides, packers, translators, invalids, reporters, and Mexican children bound for schools in Los Estados Unidos (the United States).

Spain jealously protected the borders of its New Mexico colony, prohibiting manufacturing and international trade. Missourians and others visiting Santa Fe told of an isolated provincial capital starved for manufactured goods and supplies—a potential gateway to Mexico's interior markets. In 1821 the Mexican people revolted against Spanish rule. With independence, they unlocked the gates of trade, using the Santa Fe Trail as the key. Encouraged by Mexican officials, the Santa Fe trade boomed, strengthening and linking the economies of Missouri and Mexico's northern provinces. The close of the Civil War in 1865 released America's industrial energies, and the railroad pushed westward, gradually shortening and then replacing the Santa Fe Trail.

Life on the Trail

Movies and books often romanticize Santa Fe Trail treks as sagas of constant peril—violent prairie storms, fights with Indians, and thundering buffalo (bison) herds. However, a glimpse of buffalo, elk, antelope (pronghorn), or prairie dogs was sometimes the only break from the tedium of eight-week journeys. Trail travelers mostly experienced dust, mud, gnats and mosquitoes, and heat. Occasional swollen streams, wildfires, strong winds, hailstorms, or blizzards could imperil wagon trains.

Trail hands scrambled at dawn in noise and confusion to round up, sort, and hitch up the animals. The wagons headed out, the air ringing with whoops and cries of "All's set!" and soon, "Catch up, catch up!" and "Stretch out!" Stopping at mid-morning, crews unhitched and grazed the teams, hauled water, gathered wood or buffalo chips for fuel, and cooked and ate the day's main meal, created from a monotonous daily ration of one pound of flour, one pound or so of sowbelly (bacon), one ounce of coffee, two ounces of sugar, and a pinch of salt. Beans, dried apples, or buffalo or other game were occasional treats. Crews then repaired their wagons, yokes, and harnesses; greased wagon wheels; doctored animals; and hunted. They moved on soon after noon, fording streams before that night's stop because overnight storms could turn trickling creeks into torrents. And stock that was cold in the harness first thing in the morning tended to be unruly. At day's end, crews took care of animals, made necessary repairs, chose night guards, and enjoyed a few hours of well-earned leisure and sleep.

"The Vast Plain, Like a Green Ocean"

Westward from Missouri, forests—and then tallgrass prairie—give way to shortgrass prairie in Kansas. In western Kansas, roughly at the Hundredth Meridian, semi-arid conditions develop. For Trail travelers, venturing into the unknown void of the plains could hold the fear of hardship or the promise of adventure. Long days traveling through seemingly endless expanses of tall- and shortgrass prairie, with a few narrow ribbons of trees along the waterways, evoked vivid descriptions. "In spring, the vast plain heaves and rolls around like a green ocean," wrote one early traveler. Another marveled at a mirage in which "horses and the riders upon them presented a remarkable picture, apparently extending into the air. . . 45 to 60 feet high. . . . At the same time I could see beautiful clear lakes of water with . . . bulrushes and other vegetation...." Other Trail travelers dreamed of cures for sickness from the "purity" of the plains.

Deceptively empty of human presence as the prairie landscape may appear, the lands the Trail passed through were the long-held homelands of many American Indian peoples. Here were the hunting grounds of the Comanche, Kiowa, southern bands of Cheyenne and Arapaho, and Plains Apache, as well as the homelands of the Osage, Kansas (Kaw), Jicarilla Apache, Ute, and Pueblo. Most early encounters were peaceful negotiations centering on access to tribal lands and trade in horses, mules, and other items that Indians, Mexicans, and Americans coveted. As Trail traffic increased, so did confrontations—resulting from misunderstandings and conflicting values that disrupted traditional American Indian lifeways and Trail traffic. Mexican and American troops provided escorts for wagon trains. Growing numbers of Trail travelers and settlers moved west, bringing the railroad with them. As lands were parceled out and buffalo were hunted nearly to extinction, Indian peoples were pushed aside or assigned to reservations.

Soldiers and Forts

Suspicion and tension between the United States and Mexico accelerated in the 1840s, because Americans wanted territorial expansion, Texans raided into New Mexico, and the United States annexed Texas. The Mexican-American War erupted in 1846. Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny led his Army of the West down the Santa Fe Trail to take and hold New Mexico and Upper California and to protect American traders on the Trail. He marched unchallenged into Santa Fe, and, although communities such as Taos and Mora fought back, American control prevailed. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war in 1848.

The Santa Fe Trail became the lifeline for protection and communication between Missouri and Santa Fe. From a succession of military forts such as Mann (1847), Atkinson (1850), Union (1851), Larned (1859), and Lyon (1860), the army tried to control conflicts between American Indians and Trail travelers. As the military presence grew, freighting and merchant operations burgeoned. In 1858 many of the 1,800 wagons traveling the Santa Fe Trail carried military supplies.

In 1862 the Civil War arrived in the West. Confederates from Texas pushed up the Rio Grande Valley into New Mexico, intent on seizing the territory and Fort Union, and ultimately the rich Colorado gold fields. Albuquerque and Santa Fe fell. But the tide turned at Glorieta Pass, New Mexico, on the Santa Fe Trail, in a decisive western battle of the Civil War. Union forces secured victory when they torched the nearby Confederate supply train. The Confederates abandoned hope of reaching Fort Union—and of keeping their foothold in New Mexico. The Union Army held the Southwest and its vital Santa Fe Trail supply line.

Commerce of the Prairies

The story of the Santa Fe Trail is a story of business—international, national, and local. In 1821 William Becknell, bankrupt and facing jail for debts, packed goods to Santa Fe. Capt. Don Pedro Ignacio Gallego and more than 400 troops met Becknell and five others from Missouri on November 13 outside Las Vegas, N. Mex. The Americans were welcomed and encouraged to trade. Entrepreneurs and experienced business people followed—James Webb, Antonio José Chávez, Charles Beaubien, David Waldo, and others.

The Santa Fe Trade developed into a complex web of international business, social ties, tariffs, and laws. Missouri and New Mexico merchants had connections with New York, London, and Paris.

Traders exploited social and legal systems to facilitate business. Partnerships, such as Goldstein, Bean, Peacock & Armijo, formed and dissolved. David Waldo "converted" to Catholicism—and also became a Mexican citizen. Dr. Eugene Leitensdorfer, of Missouri, married Soledad Abreu, daughter of a former New Mexico governor. Trader Manuel Alvarez claimed citizenship in Spain, the United States, and Mexico.

After the Mexican-American War, Trail trade and military freighting boomed. Firms such as Russell, Majors and Waddell, and Otero and Sellar obtained and subcontracted lucrative government contracts. Others operated mail and stagecoach services.

Trade created other opportunities. From New York, Manuel Harmony shipped English goods to Independence for freighting over the Santa Fe Trail. New Mexican saloon-owner Doña Gertrudis "La Tules" Barceló invested in trade, and trader Charles Ilfeld ran mercantile stores. Wyandotte Chief William Walker leased a warehouse in Independence, and his tribe invested in the trade. Hiram Young bought his freedom from slavery and became a wealthy maker of trade wagons—and one of the largest employers in Independence. Blacksmiths, hotel owners, arrieros (muleteers), lawyers, and many others also found their places along the Trail. Trade flourished.

Santa Fe Trail Timeline

Pre-1540

American Indians establish trade and travel routes that later become

part of Santa Fe Trail.

1540-1541

Francisco Vázquez de Coronado explores from Mexico to Quivira

(Kansas).

1601

Juan de Oñate spends 5 months traveling with wagons and artillery

through the Plains.

1739

Paul and Peter Mallet make first French trading venture to Santa Fe from

Illinois country.

"The road . . . contemplated will trespass upon the soil or infringe upon the jurisdiction of no state whatever. It runs a course and a distance to avoid all that; for it begins upon the outside line of the outside State [Missouri] and runs directly toward the setting sun, far away from all the States."

—Sen. Thomas Hart Benton, 1825

1792

Frenchman Pedro Vial travels from Santa Fe to Saint Louis for Spanish

government.

1819

Financial panic creates need for hard currency in Missouri Territory.

Adams-Onis Treaty between U.S. and Spain makes Arkansas River

international boundary.

1821

Mexico wins independence from Spain, and William Becknell's party from

Missouri is welcomed in Santa Fe.

1825

Sen. Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri arranges for U.S. Government to

survey Trail.

"The whole distance from the settlements on the Missouri to the Mountains in the neighborhood of Santa Fe, is a prairie country, with no obstructions to the route . . . . A good wagon road can . . . be traced out, upon which a sufficient supply of fuel and water can be procured, at all seasons, except in winter."

—Alphonso Wetmore, 1824

1833-1834

The Bent brothers, Charles and William, and Ceran St. Vrain build Bent's

Fort.

1836

Texas wins independence from Mexico.

1844

Trader Josiah Gregg chronicles his trips over the Trail in Commerce of

the Prairies.

"Far away from my wife and child, and six hundred miles of constant danger in an uninhabited region was not a pleasant prospect for contemplation. But I laughed with the rest, joked about roasting our bacon with buffalo chips, and the enjoyment we would derive from the company of skeletons that would strew our pathway."

—Hezekiah Brake, 1S5S

1846

U.S. invades Mexico.

1848

War ends. United Slates acquires almost half of Mexico's lands

(including New Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

1849-1852

California Gold Rush increases Trail traffic.

1851

Fort Union is established to help protect Trail commerce.

1861-1865

U.S. Civil War. 1862 battle at Glorieta Pass holds Southwest for the

Union.

1869

Trail grows shorter as railroads push westward.

"But the rejoicing at home . . . the feasts and the bailes [dances]—not to mention the wine made in their absence and saved for the occasion—was a rich compensation . . . for the hardships that were now in the dead past."

—José Librado Gurulé, 1867

1878

Railroad reaches Ratón Pass on the Mountain Route.

1880

Railroad reaches Santa Fe; Santa Fe Trail slips into history.

1906

The Daughters of the American Revolution begins erecting Trail

markers.

"Now the Santa Fe Trail belongs to the keening wind. It belongs to summer rains and to the fearful snows of winter. It is owned by the prairie dog, the jackrabbit, the rattlesnake . . . . And for a brief interval it is mine, by adoption, since I choose to stake my claim to a tiny fragment of its shining history."

—Marc Simmons, 1986

1986

Santa Fe Trail Association forms to help preserve and promote awareness

and appreciation of Trail.

1987

Congress designates Santa Fe National Historic Trail under the National

Trails System Act.

Visiting the Trail Today

(click for larger map) |

Freight wagons no longer cross the prairies, but the Trail's legacy endures as buildings, historic sites, landmarks, and original wagon-wheel ruts. The National Park Service, working with the Santa Fe Trail Association, coordinates efforts to preserve, develop, and enjoy the Trail and provides technical and limited financial help to Trail projects. Private landowners, nonprofit groups, and federal, state, and local agencies manage most Trail resources.

For information contact: National Trails System Office- Santa Fe, National Park Service, P.O. Box 728, Santa Fe, NM 87504-0728; www.nps.gov/safe. For membership and activities information contact: Santa Fe Trail Association, Santa Fe Trail Center, RR3, Larned, KS J67550; www.santafetrail.org.

Private individuals and organizations own much of the Santa Fe Trail. Not all sites are open for public use; some are open only certain hours and days. Check guidebooks and ask locally before going onto private land. Many state, county, and city museums, chambers of commerce, and tourist information museums provide Trail information. Distinctive signs mark the auto tour route that parallels the Trail. Certified Trail Properties: Non-federal historic sites, trail segments, and interpretive facilities that meet National Park Service standards for resource protection and public enjoyment may become part of the Santa Fe National Historic Trail through voluntary certification. Look for the official Trail logo.

As you visit Trail sites, please heed the following to protect yourself, the Trail, and rights of private owners. Unless otherwise indicated, hike on designated trails and keep off historic buildings, ruins, and other structures. Do not use metal detectors, dig at sites, or collect—or disturb—artifacts.

For Your Safety and Comfort

Do not assume that signs will warn you of all safety hazards. Keep watch

over children. Keep pets under physical restraint at all times. Leave

domestic stock and wild animals alone. Be aware of potentially extreme

weather conditions and the sometimes—high danger of fire on the

prairie. Many Trail sites lack amenities; plan ahead. Use public

restrooms and other facilities while in towns or developed areas.

Remember: You Are a Guest

Some private landowners are graciously allowing you to visit their

sites. Please behave as you would like guests on your own property to

behave. Leave everything the way you find it. Don't disturb the owner,

owner's family, or employees, except in the rare case of emergency,

accidents, or other problems. Owners retain the right to ask you to

leave at any time. Obey posted signs, use designated roads and parking

areas. and stay only long enough to appreciate the natural and cultural

resources of the site.

SAINT LOUIS

At this commercial hub, traders purchased and warehoused goods and

supplies for westward freighting on the Trail. Mexican goods were sold

or shipped east.

FRANKLIN

William Becknell's successful 1821 trip made Franklin the first eastern

terminus of the international Trail trade. Floods in 1826 and 1828

contributed to its demise.

INDEPENDENCE

Between 1827 and 1856, wagonmarkers, blacksmiths, and other merchants

created a bustling industry here to support and outfit Santa Fe Trail,

and later Oregon Trail and California Trail travelers.

WESTPORT

By 1853, Westport had become the Trail's main eastern terminus. The

Civil War and the railroad brought its Trail heyday to an end.

COUNCIL GROVE

The 1825 treaty signed here with the Osage Indians ensured safe travel

to this "prairie Eden." Westbound wagon trains gathered here to form

larger caravans.

THE GREAT PLAINS AND THE PRAIRIES

Until the arrival of Europeans, this was the home for many American

Indian tribes that hunted, farmed, and roamed across this vast

landscape.

FORT LARNED

From this fort, established in 1859. the U.S. Army provided protection

for caravans, stagecoaches, and other Trail travelers.

WET/DRY ROUTES

Trail travelers chose between the "wet route," which afforded good

grazing and water for large numbers of stock, and the shorter but

water-limited "dry route."

ARKANSAS RIVER

Rivers were serious obstacles. During crossings, injury to people or

animals and damage or loss of wagons or cargo were ever-present

dangers.

CIMARRON ROUTE

This was the shortest and the original wagon route between Santa Fe and

Missouri. The easternmost 60 miles offered no reliable water and was

called La Jornada (The Journey).

MOUNTAIN ROUTE

Called the Ratón or Bent's Fort Route during Trail days, it was longer

and more difficult than the Cimarron Route, but considered safer.

BENT'S FORT

The Bent brothers and Ceran St. Vrain built a commercial trade depot in

1833. It served American Indians, fur traders, and Trail travelers for

17 years.

RATÓN PASS

The difficult crossing over Ratón Pass was a major obstacle to Trail

travel. In 1865, entrepreneur Richens "Uncle Dick" Wootton eased the

journey by building a toll road.

FORT UNION

Three successive forts were built to protect Trail travelers and to

serve as a major military supply depot for the Southwest.

PECOS PUEBLO

Long a trade center for Pueblo ana Plains Indians, this pueblo and later

Spanish mission were abandoned in 1838, becoming only a landmark along

the Trail.

SANTA FE

This provincial capital of Nuevo Méjico was an isolated outpost until

the Santa Fe Trail turned it into a commercial center.

Source: NPS Brochure (2004)

|

Establishment Santa Fe National Historic Trail — May 8, 1987 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

"A Faithful Account of Everything": Letters from Katie Bowen on the Santa Fe Trail, 1851 (Leo E. Oliva, ed., extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 14 No. 4, Winter 1996-1997)

A Road of Culture and Commerce: Introduction (Thomas E. Chávez, extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 14 No. 4, Winter 1996-1997)

American Indians and the Santa Fe Trail (James Riding, June 23, 2009)

Banditti on the Santa Fe Trail: The Texan Raids of 1843 (Harry C. Myers, extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 14 No. 4, Winter 1996-1997)

Bibliography (Adult/Educator) (2021)

Bibliography (Youth) (2021)

Business Techniques in the Santa Fe Trade (Lewis E. Atherton, extract from Missouri Historical Review, Vol. 34 No. 3, April 1940, ©The State Historical Society of Missouri)

Certification Guide, Santa Fe Trail National Historic Trail (September 1997)

Comerciantes, Arrieros, Y Peones: The Hispanos and the Santa Fe Trail (Merchants, Muleteers, and Peons), Special History Study, Santa Fe National Historic Trail (HTML edition) Southwest Cultural Resources Center Professional Papers No. 54 (Susan Calafate Boyle, 1994)

Conflict and Commerce on the Santa Fe Trail: Fort Riley - Fort Larned Road, 1860-1867 (David K. Clapsaddle, extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 16 No. 2, Summer 1993)

Comprehensive Management and Use Plan and Environmental Assessment, Santa Fe National Historic Trail Draft (April 1989)

Comprehensive Management and Use Plan: Santa Fe National Historic Trail (May 1990)

Comprehensive Management and Use Plan Map Supplement: Santa Fe National Historic Trail (May 1990)

Eastward Ho! The Mexican Freighting and Commerce Experience Along the Santa Fe Trail (Sterling Evans, extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 14 No. 4, Winter 1996-1997)

Enos and Jennie Culver Memoir, Travel Diary and Correspondence while traveling the Santa Fe Trail and El Camino Real 1869-1871 (Joy Poole and Mike Olsen, undated)

Feasibility and Concept Plan: The New Santa Fe Trail (The Conservation Fund, January 1992)

Fort Union and the Santa Fe Trail (Robert M. Utley, extract from New Mexico Historical Review, Vol. 36 No. 1, 1961, ©University of New Mexico)

Fort Union and the Santa Fe Trail: A Special Study of Santa Fe Trail Remains At and Near Fort Union National Monument, New Mexico (Robert M. Utley, December 1959)

Santa Fe National Historic Trail, Missouri, Kansas, Colorado, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Overview (April 2021)

Indian Policy on the Santa Fe Road: The Fitzpatrick Controversy of 1847- 1848 (Robert A. Trennert, extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 1 No. 4, Winter 1978-1979)

Interpretive Prospectus, Santa Fe National Historic Trail (September 1991)

John Jurnegan: An autobiography of travels to Fort Laramine over the Oregon and California Trail and along the Santa Fe Trail (1851-1868) (Joy L. Poole, ed., undated)

Junior Ranger Activity Book, Santa Fe National Historic Trail (2012; for reference purposes only)

Missouri and the Santa Fe Trade (F.F. Stephens, extract from Missouri Historical Review, Vol. 10 No. 4, July 1916, ©The State Historical Society of Missouri)

Myth and Memory: The Cultural Heritage of the Santa Fe Trail in the Twentieth Century (Michael L. Olsen, extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 35 No. 1, Spring 2012)

National historic trail awareness and experience, Santa Fe, Oregon, and California National Historic Trails (extract of entire report, undated)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail, 1821-1880 (The URBANA Group, March 1, 1993)

Historic Resources of the Santa Fe Trail, 1821-1880 Amended submission (Kansas State Historic Society Staff, Spring 2012)

"Not Occupied...Since the Peace:" The 1995 Archaeological and Historical Investigations at Historic Fort Marcy, Santa Fe, New Mexico (Cordelia Thomas Snow and David Kammer, December 6, 1995)

Old Ruts and New: The History of Santa Fe Trail History (Michael L. Olsen, extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 14 No. 4, Winter 1996-1997)

Park Newsletter

2010: September

2013: Spring

2014: Spring

2020: Fall

Report on the Santa Fe Trail (Ray H. Mattison, 1958)

Santa Fe Trail — M. M. Marmaduke Journal (F.A. Sampson, extract from Missouri Historical Review, Vol. 6 No. 1, October 1911, ©The State Historical Society of Missouri)

Santa Fe National Historic Trail (Map) (1991)

Santa Fe Trail: A National Scenic Trail Study (Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, July 1976)

Some Aspects of the Santa Fe Trail 1848-1880 (Ralph P. Bieber, extract from Missouri Historical Review, Vol. 18 No. 2, January 1924, ©The State Historical Society of Missouri)

Strategic Plan, Santa Fe Trail Association (April 2013)

That Broad and Beckoning Highway: The Santa Fe Trail and the Rush for Gold in California and Colorado (Michael L. Olsen, undated)

The History and Archaeology of the Historic Fort Marcy Earthworks, Santa Fe, New Mexico (Mary June-el Piper, ed., 1996)

The Indian Threat Along the Santa Fe Trail (Susan Koester, extract from The Pacific Historian, Vol. 17 No. 4, Winter 1973; ©University of the Pacific for the Holt-Atherton Pacific Center for Western Studies)

The Journals of Capt. Thomas Becknell from Boone's Like to Santa Fe, and from Santa Cruz to Green River (William Becknell, extract from Missouri Historical Review, Vol. 4 No. 2, January 1910, ©The State Historical Society of Missouri)

The memoir and diary of Rebecca Mayer on her 1852 honeymoon along the Santa Fe Trail and down El Camino Real with her merchant husband Henry Mayer, fifty men and five hundred mules (Joy Poole, ed., undated)

The Santa Fe Trail (William E. Brown, Ray H. Mattison, Roy E. Appleman and Robert M. Utley, 1963)

The Santa Fe Trail (G.C. Broadhead, extract from Missouri Historical Review, Vol. 4 No. 4, July 1910, ©The State Historical Society of Missouri)

The Santa Fe Trail: Road of Commerce and Adventure (Ray E. Jenkins, extract from The Denver Westerners Roundup, Vol. 68 No. 4, July-August 1992; ©Denver Posse of Westerners, all rights reserved)

The Wet and Dry Routes of the Santa Fe Trail (David K. Clapsaddle, extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 15 No. 2, Summer 1992)

Wagon Tracks: Quarterly Publication of the Santa Fe Trail Association (1986-2020)

Wagons on the Santa Fe Trail 1822-1880 (Mark L. Gardner, September 1997)

Women on the Santa Fe Trail: Diaries, Journals, Memoirs. An Annotated Bibliography (Marc Simmons, extract from New Mexico Historical Review, Vol. 61 No. 3, 1986, ©University of New Mexico)

safe/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025