|

San Juan Island

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 4:

San Juan Island National Historical Park Management

Since its creation in 1966, park staff has worked to define the park, its goals, and its operating needs. Early in the planning stages, it was determined by a NPS Western Regional Office planning team that the staffing levels at the park would be kept low and would rely on regional office staff for technical assistance support. By comparison to other parks in the region with similar types of resources and acreage, the park staff has remained small. This results in a management situation where staff serves in different roles as needed.

Since the management record for the park is incomplete, there are management decisions for which the reasoning behind them remains unknown. There are, however, a few general characteristics of park management that are identifiable over the years. The first characteristic is the feeling that, even though the park has existed for thirty-three years, it seems new. To some NPS staff, both at the park and in the region, the park still feels and operates like a new park that has yet to come fully into the system. In interviews with past superintendents, the idea that the park still felt like a new park when they came "on board" was a recurring theme.

The island environment also shapes park management, in ways that other parks in the region have not experienced. Location adds a special twist to park management on several levels. First, the rural quality of the island and its small population sometimes leads to difficulty getting or maintaining supplies and equipment. There are no super-warehouse stores on the island, and prices for certain materials can be higher than on the mainland. The nature of the island tourist economy and the vacation property market also lends to a higher cost of living. An additional factor career NPS staff considers in looking at openings with the park is the lack of job opportunity available for spouses or other family members around the islands. The park hasn't traditionally attracted high levels of career NPS personnel for positions outside of superintendent and chief ranger. A good percentage of staff has come from the island or nearby mainland communities.

On a larger scale, there is something to be said for "island time," meaning action on the island can move at a slower pace. In 1985, the regional office sent a study team to the park to review the management structure and make recommendations on how the park could be more effectively managed. When Deputy Regional Director Bill Briggle wrote to Superintendent Hastings to inform him of the study team's arrival and intentions, he noted that he asked Darryll Johnson, the regional sociologist to "analyze the impact of insular living on the staff, their attitudes, productivity, etc., in hopes of gaining greater understanding of an island work environment and the possible problems facing our people while on such an assignment." [1] The concept is an intangible and the true level of its impact over the years is elusive. The only thing known for certain is that the concept was considered at regional levels of management and that thousands of people "escape" to the island every year to enjoy its attitudes and environment. It is the reason people retire there.

The island environment can be said to influence another characteristic of park management: the attitudes of NPS staff from other offices. One can reason that island time is partially responsible for the perception that the park is a "sleepy" park, with not much activity occurring. This is not true; there is plenty going on, and plenty that could be going on given appropriate staffing and funding levels.

That the park is perceived as sleepy is derived from research interviews of NPS park staff and their observations about the NPS staff at region, Washington, D.C., and even at other parks. There is the almost unanimous opinion among park staff that, for many years, the park was treated as a great place to get to visit. All park staff referenced this in some way or another. NPS personnel invited to the park for the purpose of assessing park needs would see the park, tour the island, and then leave. Park staff expressed difficulty in getting further response after such visits, and some honestly were left with the impression that the trip in itself was really the goal, and not to resolve any of the park's problems or issues. This is not meant to imply that all staff visiting the island have not followed through with assistance; it is only meant to convey a message that was consistent in park staff interviews completed for this history.

The Pacific Northwest region is home to three big natural parks, Olympic, North Cascades, and Mount Ranier. It is a consistent theme in the region that all the small historical parks, San Juan among them, has a difficult time receiving a commitment from upper management at the regional and national levels in the shadow of these three dominant parks. So while regional technical staff tried to assess, program, and lobby for management needs at the park, they are equally frustrated by the lack of support and lobbying power coming from upper management.

Frustration has also been an intangible force at work at the park and was evident in 80% of the interviews the author conducted. Job satisfaction is based on a feeling of achievement and accomplishment; this is true for any work environment. A great deal of park planning has never been implemented, despite work by the staff to get support and funding for a variety of projects and programming. The general feeling the author observed is that staff basically operated on survival mode, that a majority of their time was spent trying to maintain basic operations, but not generally making progress on issues or projects. This atmosphere is a stressful one and it results in burn out of personnel. The idea that park staff believed that upper level NPS management was not listening has also contributed to this problem.

With those characteristics underlying the basic framework of park management, a review of park development shows that the park has spent a majority of its history trying to define itself, its goals and programming needs under the shadow of the region's big three parks and the frustration created by the lack of support from upper management in implementing recommended planning efforts.

Development Planning

The first step taken by the National Park Service following passage of the 1966 legislation was to develop a plan of action. A planning team of individuals from the western regional and Denver Service Center offices was assigned to develop a master plan, which was approved in October 1967. Bennett Gale would continue to serve as the NPS representative until 1969, when Superintendent Carl Stoddard was hired. The regional office and the Denver Service Center would continue to play a major role in the completion of initial development outlined in the park's master planning document.

Master Plan, 1967

The master planning document for San Juan Island N.H.P. is a standard National Park Service document, offering basic statistical information about the site and identifying major planning issues/problems, and offering solutions to aid in the establishment and formal dedication of the park. The plan offers and prioritizes recommended actions for initial site development.

Primary objectives for San Juan were listed as follows: acquire lands identified as necessary for interpretation, protection, and development; develop a program of restoration and stabilization at both camps to preserve the historic settings; develop necessary facilities for the interpretation of the historic story; develop a program to maintain and protect the historic scene and structures; utilize the recreational opportunity of the park, provided that it does not conflict with the park's basic purpose; and encourage and preserve through local interest and action the complementary stories and artifacts of the San Juan Islands. The plan also provided a scope of collections statement, an interpretive theme, and an architectural theme.

In summarizing the plan's programming intent, it states the general operating mission of the park to be the preservation and interpretation of the historic story of joint occupation and the "Pig War." To this end, the park would complete certain stabilization and limited restoration of the historic scene, and develop visitor access and parking, interpretation, picnicking, and camping at both American and English Camp sites. The plan also called for: establishment of a small maintenance area; limited residential development; and the establishment of a contact station in Friday Harbor, with placement of administrative headquarters in town. Finally, the summary suggests that the basic components of this development should be completed by October 21, 1972, the centennial anniversary of the peaceful settlement of the boundary dispute. This occasion would serve as the formal dedication of the park.

Following this summary, the plan introduces factors that would affect all development of the park and which would continue to guide park planning. In addition to a budget limitation of $3,542,000 for lands acquisition, planning would also be shaped by promises given during public hearings to limit recreational facilities to auto and boat campgrounds, restore English Camp structures and the American Camp Redoubt, and provide Jim Crook with life tenure for his house plus use of three surrounding acres. [2] Jurisdiction would be coordinated through cooperative agreements with local government or private individuals. These items form the basic minimum planning needs to be met and achieved through this planning document.

The document identified major problems facing site development and outlined solutions and existing opportunities for park development in the following specific management areas: lands acquisition, development, research needs, resource management, maintenance and protection, and visitor use.

For lands acquisition, the plan pointed out the following problems: the NPS did not actually have title to any necessary lands yet; the title to tidelands adjacent to the proposed park boundary was divided between private and state ownership; no initial contact point in Friday Harbor existed; and boat use between Guss Island and English Camp could impact the historic scene. Recommended solutions included:

- acquire lands identified in boundary establishment planning

- acquire control of tidelands adjacent to the park through agreements, easements, purchase, or donation

- obtain suitable space near the ferry landing as an information office and administrative headquarters

- obtain scenic rights and restrict water use at English Camp and Guss Island

Research needs identified for park programming dealt strictly with the location and appearance of historic structures. The plan called for a research study to determine the following information: locate all historic structures; determine their size, appearance, and use; identify existing structures which were intrusive elements on the historic scene; identify historic structures which were removed from the park; and provide information to guide restoration of the structures, remains, and the historic scene.

The only natural resource management need identified is one that should surprise no one familiar with the island: rabbits, and lots of them. The document called for the development of a control and action plan to reduce and eventually eliminate the problems of over grazing and burrowing by rabbits at American Camp, which threatened to destroy the native habitat typical of the historic scene and perhaps undermine the stability of historic structures.

With regards to maintenance and protection, fire was identified as a threat to the park, particularly to all historic structures. The plan recommended coordinating cooperative agreements with local and state agencies for mutual assistance in case of a fire, as well as for staff fire training, visitor programs in fire safety, and the installation of fire suppression systems in park buildings.

The plan identified certain visitor uses at the sites to be detrimental and destructive to the historic setting. In addition, no interpretive facilities were in place, no personnel or management were available for visitor safety or resource protection, and no overnight facilities were available. The plan recommended the limitation of visitors to compatible use only, development of interpretive facilities at both American and English Camps, development of on-site residences for park staff to provide 24-hour protection, and the development of a limited number of campsites for auto and boat users.

A number of items were identified as deficient or nonexistent. Proper utilities did not exist at either site to accommodate NPS development. Water, sewer, power, and telephone needs and sources had to be identified. Burial of all power lines to eliminate impact on the historic setting would be necessary. Specific needs included roads, parking, and trails at both camps; seasonal employee quarters; maintenance facilities; redirection of incompatible county roads; elimination of Crook family buildings intruding on the historic scene; and the placement of floats on all docks and possible dredging to accommodate boat use.

After identifying what needs existed to establish and begin basic park operations, the document prioritized those needs, breaking them into three categories: pre-construction, construction, and operational.

For pre-construction, the document recommended acquisition of lands; acquisition of office space in Friday Harbor; assignment of staff to provide practical and immediate interim park operations; stabilization of structures at English Camp; and preparation of an interpretive prospectus and request for bids for structural and site rehabilitation, construction, and an exhibit plan.

Under the construction phase, the park would begin site rehabilitation, historic building restoration, and park service facilities construction, acquisition of remaining lands, fulfillment of staffing needs, and preparation of the interpretive devices called for under the interpretive prospectus. Completion of any shoreline developments and the beginning of full park operations would also fall under the construction phase.

|

| Land ownership and use map, 1969 Master Plan. (click for larger image) |

Under the final, operational phase, the park would develop a program of long-term maintenance providing preservation and protection of structures and grounds, acquisition of any inholdings, and hiring of staff for full park operations.

With a planning document in hand, the NPS moved ahead with development for the park. First and foremost, the NPS needed to acquire title to the lands identified for inclusion in the historical park.

Lands Acquisition

Unfortunately for public relations matters, fifteen of the tracts acquired by the NPS ended in condemnation proceedings, and took until 1972 to complete. As noted by NPS historian John Hussey in the park's proposal document, changing land use patterns meant the lands being acquired by the NPS were prime residential and vacation property. Owners knew that land values were on the rise; the demand for seasonal vacation property was growing.

On June 16, 1965, private property owners identified in the American Camp and English Camp acquisitions were as follows:

American Camp Owners Acres * 1, 2, 3 Kenneth Dougherty (1/3 each) 75 George J. Franck (1/3 each) 440.79 Richard N. Franck (1/3 each) 4 Fredrick W. Whitridge (improved) 77.75 5 F.V. Landahl 1.20 6 Harold J. Jones 49.46 7 Leslie M. Bitner 20 8 Roland F. Gray 2.32 9 Randall V. Green 1.70 10 Orville R. Clary 1.95 * 11 T.J.R. Corps (improved) 281.62 * 12 Maynard Monette 26 13 Clifford L. Dightman 81.08 14 Floyd L. Foreman (improved) 5 15 James F. Bolster 3.37 * 16 Jack D. Havens 4.30 * 17 Alfred Kallicot 1.38 * 18 Colby Crabtree 2.76 * 19 F.H. Golm 1.38 * 20 D.C. Walker 3.45 21 Elizabeth McCain 3.62 22 R.K. Smith 1.50 * 23 L.L. Kelly 3 * 24 Brian Griffin 2.76 25 Edward O'Conner 3 * 26 Charles Schmidt 2.50 27 Lieth Wade 2.70 * 28 Harold J. Rodgers 60 29 C. Turick 20 30 Raynold V. Dickhaus 1.51 31 Alton R. Boyce 2.01 32 Norris Bartley (improved) .92 33 William V. Catlaw 1.48 34 John Y. Fleming 31.76 Total private property - American Camp 1,217.27

English Camp Owners

Acres1 Jim Crook (improved) 184.98 2 Harly S. Jones 78.92 3 Agnes Jamison (improved) 1.40 * 4 Roche Harbor Lime and Cement Co. 80 5 Fern Nicoll Ingoldsby 73.90 Total private property - English Camp 419.20 * Indicates condemnation proceedings

Condemnation proceedings for tracts of non-willing sellers totaled 548 acres and were settled in federal district courts in Seattle, Bellevue, and Friday Harbor. At issue was the value of the properties: fair market value for the acreage did not necessarily equate to the dollar value that could be gained if properties were subdivided and sold as residential lots. To gain a perspective of the development plans that were alternately considered, the Jas. F. Bolster Agency in Bellingham at one time was prepared to sell 100' x 500' foot and 100' x 200' foot lots for the T.J.R Corps property along the stretch of American Camp's southern edge at $17.00 per frontage foot. Plans called for 66 individual lots. [3]

Washington State park lands were required under federal legislation to be donated, not purchased. In 1967, the Washington State legislature approved donation of their properties under the following conditions: that the National Park Service had ten years to develop the site or it would revert to state ownership and that title to tidelands remained with the state. The state parks commission also requested that the NPS help facilitate a land transfer between the state and the Department of the Interior for lands bordering state park property elsewhere in the Washington.

In all, the park acquired 1,752 acres at a total cost of approximately 3.5 million dollars. [4] In any condemnation situation, there are going to be ill feelings on behalf of those losing their property. San Juan Island was no exception, and the landowners in condemnation proceedings, most of who remained on the island, provided a source of anti-park sentiment on the island. This resentment has quieted as time has passed.

|

| Detail of development residential lots, Bolster Agency, no date |

Carl Stoddard, 1969-1974

Carl Stoddard was a resource manager at the Western Regional Office prior to his tenure at San Juan. As the park's first superintendent, Stoddard's primary tasks were outlined in the pre-construction phase of the master plan. First and foremost was the completion of lands acquisition. In addition, an office and staff needed to be established to begin basic park operations.

During the 1970s, Stoddard's staff numbered 3 to 4 employees, with 2 or 3 seasonals and approximately 12 to 15 Volunteers In Parks (VIPs). Office space had been arranged through General Services Administration (GSA) in the Carter Building on Spring Street in Friday Harbor in 1967. Later that year, a trailer arrived to serve as seasonal housing and was placed in a trailer park in Friday Harbor. [5]

A debate ensued over whether or not the park should have an administrative office in Friday Harbor, as suggested in the master plan. In his master plan comments, Regional Director John Rutter gave several reasons why he did not think that offices needed to be in Friday Harbor on GSA-leased property. First, he estimated that most arrivals on the island would be in cars and parking at an information station would create traffic congestion. Second, staffing levels were not going to be large enough to cover three stations. Third, he believed "any Superintendent worth his salt" would be in town developing the necessary public relations contacts. [6] However, planning for offices at either camp site to replace the office space in Friday Harbor would not occur until the lease for the Carter Building space was terminated in 1977. Even then, it would be temporary and last minute planning.

The need for a maintenance facility was met when the Jameson property was acquired at English Camp. The property was an improved lot with a house and shed. The shed building was modified to serve as the park's maintenance facility.

Stoddard wrote the first management objectives for the park, which were approved in 1970. The management objectives reiterated the park's legislative objective and those commitments the NPS made during public hearings. The document provides an assessment of park resources and environments, and identifies resources relocated outside the park boundaries (possible American Camp structures and the English Camp Hospital). Stoddard's management objectives established park visitation at 25,000 a year, with half of the summer visitation arriving by boat at English Camp. [7]

|

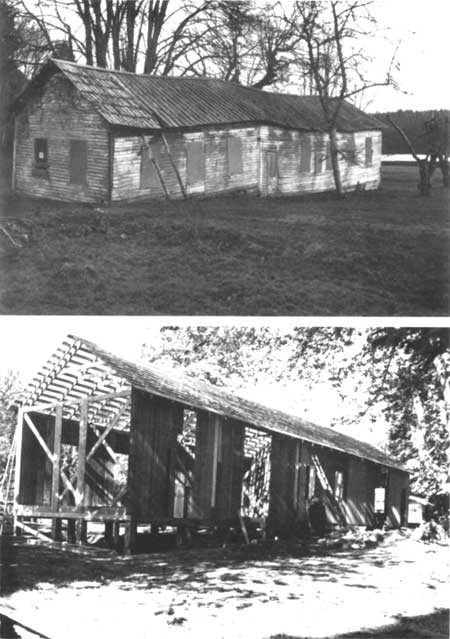

| Commissary prior to restoration, 1970. |

The document lists several objectives for general management, resource management, and visitor use. For general management, the park was to be managed as a small park, relying on the Seattle regional office for assistance. Management would oversee lands acquisitions and the park would provide year-round visitor services, maintain close relationships with local, state, and other federal agencies, work with local organizations and private owners to help preserve the island's historic resources, and observe the 1972 centennial of the boundary dispute. All NPS structures would be constructed in an unobtrusive style using muted colors and natural materials.

For resource objectives, the document stated in general that park resources were to be managed with the intent to preserve them for long-term stability. In addition, the park was to engage in an intensive research program of structure restoration; develop a program of restoration and stabilization at both camps to maintain the historic scene; and work with local, state, and other federal agencies in the area to accomplish a rabbit control program.

The park's visitor use objectives included interpretation of the historic events leading to the Pig War, joint military occupation, and peaceful arbitration settlement; broaden interpretation to include environmental education in coordination with local schools; provide visitor facilities and recreational developments where opportunities existed (in 1970, planning still involved providing campsites at American Camp), as long as facilities did not impact the historic scene; and provide for visitor safety and protection.

Following the development of these management objectives, a good deal of Stoddard's efforts went into fulfilling the research and restoration needs of the historic structures at English Camp, fulfilling one of the promises made during the public hearings process. In 1970, the Commissary and Barracks structures underwent restoration work and were painted. The Blockhouse was rehabilitated and painted in 1971. In 1972, staff reestablished the flagpole and worked to restore the English Camp formal garden. Don Campbell, Pacific Northwest Region (PNR) park planner and landscape architect, assisted in the garden's design. [8] General maintenance was completed at the English Camp cemetery, and studies into other structures were underway, including a review of the structure on the property of Harold Lawson believed to be the English Camp Hospital. Stoddard spent time in Victoria, British Columbia, researching English Camp in the regional archives. He noted that staff at Canadian repositories took great interest in the preservation of English Camp. [9]

|

| The Barracks, prior to and during restoration, c.1970. |

In 1972, NPS historian Erwin Thompson completed the Historic Resource Study for both camps, which included a social/political review of the historical events at the park. The study provides a detailed analysis and, when possible, locations of structures (existing and lost) at both camps during the military occupation. It also identifies the location of Bellevue Farm, San Juan Town, and Lyman Cutlar's potato patch. Studies determined that the McRae house, ALThough having undergone some additions, was an original American Camp structure. The Lawson building was also determined to be the Hospital from English Camp and was donated to the NPS by owner James Mathis in 1973.

Superintendent Stoddard established the cooperative agreement, which brought the University of Idaho archaeological field school to the park for structural research beginning in 1970. In 1971-73, interpretive wayside exhibit plans were developed for both camps. In 1973, contracts were awarded for an exhibit shelter at American Camp and a small exhibit was installed in the English Camp Barracks structure after its restoration.

Two major moves were completed in 1974, just prior to the transfer of Carl Stoddard. The Hospital building, donated the previous year, was returned to English Camp. Research of historic photographs and archaeological evidence determined the structure's proper location on the parade ground. Historic photographs proved more useful. Archaeological evidence completed by the university field school was not conclusive in locating the original structure's placement. The Warbass house, which was determined to be one of the original laundress' quarters, was moved back to American Camp from its location near Friday Harbor. Restoration work on both structures would be completed at a later date.

|

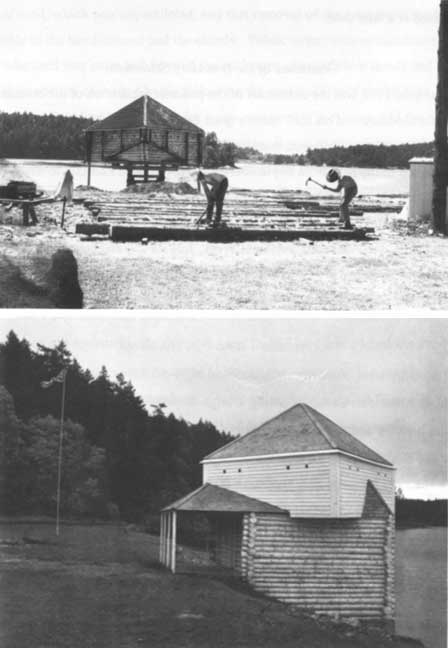

| The Blockhouse during and after restoration. |

Centennial of the Boundary Settlement

The year 1972 was the centennial of the peaceful arbitration of the boundary dispute, and Stoddard and his staff spent a great deal of time coordinating ceremonial planning. Robert Reynolds joined them in their efforts, a Pacific Northwest Region ranger assigned to the park from September 17 to November 11 strictly to assist with planning for the October ceremonies. Activities included a Memorial Day service at English Camp cemetery with visiting Canadian troops; a 4th of July celebration at American Camp; activities for Centennial Week, July 23-29; and ceremonies on Centennial Day, October 21, 1972. The Centennial Day ceremony included officials representing the United States, Canada, England, and Germany. Assistant Secretary of the Interior Richard S. Bodman was the principal speaker, and marching and ceremonial units from the United States and Canada performed. The ceremonies were well received and attended, and several local organizations were involved in the activities and services.

American Camp By-Pass Road

All development planning included one high-priority task: replacement of the county road at American Camp. Cutting alongside the Redoubt, the road not only impacted the historic scene but also contributed to incompatible use and erosion. In order to preserve the Redoubt, the park constructed a new by-pass road with the intention of exchanging the new by-pass with San Juan County for a portion of the county road. The old road would be restored to the conditions of the historic setting. Under Stoddard, planning for the by-pass road was completed and negotiations began with the county for exchange of property. In 1974, the by-pass road was constructed and opened to traffic on December 20. [10]

However, the issue became hotly contested when neighbors and other individuals on the island discovered the planned exchange of property and road closure. Letters and a petition from neighbors and community members expressed opposition to the road exchange on the grounds that islanders should not have to give up the view along that portion of road, which was unparalleled, and that removal of the road made the Redoubt inaccessible to the handicapped and the elderly. Public outcry was so significant that the county, who until that point had favored the exchange, changed their minds and voted not to vacate the portion of road. Shortly following the construction of the by-pass road, Superintendent Stoddard left the park for a new assignment in Alaska, and the change in management may have hurt the negotiation process. It was an unfortunate setback for park development. The by-pass road remained open and available for use in conjunction with the county road. Management decided to back off the issue until more favorable public relations conditions existed.

Segismand Zachweija, 1974-1980

Coming on board in April 1974, the first task attended to by Superintendent Zachweija was the collapse of negotiations with San Juan County for the road exchange. Zachweija continued the management goals and program planning initiated by Stoddard, which included a new general management plan to replace the park's initial master plan.

In 1975, NPS historical architect Harold La Fleur, Jr. completed a List of Classified Structures inventory for the park, and in 1977 he completed the study entitled Historic Structures Report: Architectural Data for the American Camp McRae House/Officers' Quarters and Laundress' Quarters and the English Camp Hospital. In 1978, a contract for rehabilitation work on the McRae house was awarded. Between 1977-78, park staff worked on audio-visual scripts for interpretive programs for use in the English Camp Barracks. The park also worked to complete the first resource management plan for the park, which was approved in 1979.

Complicating things for management, GSA informed the park in 1977 that the landlord for the Friday Harbor office was terminating their lease. The landlord had given the NPS two or three months notice to be out of the space and GSA informed the park that no other suitable space was available in town and offered no other solution. A building regulation in place in 1977 limited building construction on site to under $3,000 unless approved by Congress. [11] However, a trailer could bex installed on site, so Laurin Huffman, regional historical architect, designed a structure for use as a temporary headquarters building until funding and planning could be completed for a permanent visitor facility/office building. The plan was to move the trailer to North Cascades National Park for their use after completion of a permanent visitor center at San Juan.

|

| The park trailer serving as the administrative headquarters. |

Huffman designed the trailer in a hurry and submitted it to procurement but no one bid on the job. After a quick day-and-a-half redesign, Huffman sent out a new design, which was contracted to Evergreen Mobile in Issaquah, Washington. Walt Manza worked to complete site construction at American Camp. [12]

Manza's work was jeopardized early on when the largest ferry making runs to San Juan Island, and for which Huffman had designed the trailer to fit on, broke down. The project was delayed until the rudder on the Kaleetan was repaired and the large ferry put back on island runs. The trailer was then trucked and ferried to the island and assembled onsite. In the meantime, the lease ran out on the office space in the Carter Building, and a trailer previously used as seasonal housing had to suffice as the administrative headquarters until the new trailer structure could be transported and assembled. This "temporary" structure is still in use today, as a visitor contact station containing lobby exhibit space. Located at American Camp, it also houses offices for interpretation, resource management, and the park library.

General Management Plan, 1979

Programming for a new general management plan (GMP) for the park began in 1973. The 1967 master plan was intended to get the park through its initial development phase and most of those objectives had been completed or determined to be outmoded by park staff. [13] A new general management plan identified current development needs and the programming/appropriation of funds to meet those needs.

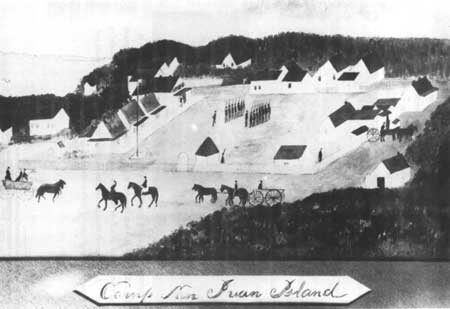

|

| American Camp as drawn by an unknown artist, detailing the parade ground and buildings. |

The park's 1979 general management plan identified the following management objectives:

Historic resources: to identify, evaluate, protect, and preserve the historic scene and resources of English Camp and American Camp, as well as prehistoric remains, in accordance with historic preservation laws, management policies of the National Park Service, and the purpose of the park.

Natural resources: to manage natural resources in order to recreate and perpetuate the historic scene; to work cooperatively with the state of Washington in managing tidelands; and to identify threatened or endangered species and preserve their habitat.

Interpretation: to foster understanding and appreciation of the historic events that occurred from 1853 to 1871 on San Juan Island in connection with the final settlement of the Oregon territorial boundary dispute between the United States and Great Britain, including the Pig War of 1859.

Visitor use: to encourage visitor use and enjoyment of the park through provision of adequate facilities and services for activities that are compatible with the cultural, natural, and scenic values of the park.

Acquisition of information: to acquire information through archaeological investigations, documentary research, and other means, as appropriate, for the purpose of preserving and interpreting the park.

Cooperation: to cooperate with other agencies, private groups, and the public for the purpose of protecting and encouraging compatible use and development of the island's resources.

The 1979 GMP placed the highest priority on the preservation of historic structures at American Camp. Restorations at English Camp had taken place as early as 1970, but the Officers' and Laundress' Quarters at American Camp remained unrestored. The planning team, in combination with public opinion, believed that created an imbalance between the two camps.

|

| Historic Base Map, American Camp (click for larger image) |

|

| Historic Base Map, British Camp (click for larger image) |

Resource management needs identified in the 1979 GMP covered a variety of restoration, management, research, and reconstruction projects. At English Camp, minor relocations to the flagpole and the formal garden were planned, as well as developing picnic tables and an information office outside the historic area. Larger projects included the restoration of the Hospital structure; reconstruction of the parade ground fence; marking of the foundations of all non-extant buildings; research and replanting of the formal garden; and monitoring/research of the Garrison Bay shoreline.

The majority of resource development projects were at American Camp, and focused on restoration of the Officers' and Laundress' Quarters. The plan also recommended the reconstruction of the picket fence enclosing the parade ground, all HBC fences, and the marking of all non-extant American Camp and HBC structure foundations. Projects designed to recreate the historic setting of 1859-72 included the burial of intruding power lines, the reconstruction of the HBC vegetable garden, and reestablishment of the forest landscape north of the campsite. Temporary headquarters were to be moved to American Camp and some form of rabbit control developed. In addition, studies of the relationship between eagle and other raptors and populations of non-native wildlife species at American Camp were recommended. Finally, the plan called for cataloging and photographing the park collections.

A number of general development needs were identified to provide better visitor access and to give park staff a better work environment. English Camp needs included: re-graveling the access road, expanding the lower parking lot (if determined necessary), widening and graveling the Garrison Bay access road and parking area, developing a picnic site at Garrison Bay, designing and constructing a parking lot and a trail to Young Hill, and erecting a commemorative plaque for Jim Crook, recognizing local efforts to preserve English Camp. At American Camp, the plan called for creating a parking area

in front of the interpretive shelter, designing and constructing a park headquarters, and utilizing non-historic buildings for park operations or removing/salvaging them.

The GMP called for development of a permanent visitor facility and offices, employees quarters, a maintenance facility, and construction and installation of a boat dock and mooring buoys. Despite previous planning attempts, the county and by-pass roads at American Camp were both listed as "no change", indicating the park planned to continue the status quo for the contentious issue of the county and by-pass roads. [14]

Visitor use and interpretation needs for English Camp included the proper inventory and assessment for retention or donation of the remainder of Jim Crook's equipment that was left on the property. No changes were identified for the Barracks exhibits.

At American Camp, identified interpretation needs included a new interpretive sign at the Redoubt. The GMP also considered re-designation of the Jakle's Lagoon Road into a nature trail with interpretive markers placed for more involved natural history interpretation. The existing interpretive shelter was identified as too small and limiting for proper interpretation and visitor needs and a new facility for the camp was recommended.

The GMP also recommended securing office space in Friday Harbor for a staffed information office. This recommendation carried over from initial park planning, but a lack of adequate space in Friday Harbor, in addition to an unconvinced regional office, would delay this move. The plan also identified the need for road signs identifying mileage to two park units and the need for interpretive exhibits or, at minimum, brochure dispensers for placement aboard island-bound ferries to help guide visitors to the park.

The GMP scheduled each of the proposals into three, five-year phases, with dollar amounts associated with each specific project. Phase one projects identified what park management believed was the highest priority for park development; specifically, bringing American Camp up to the same level of restoration and quality as the historic scene that existed at English Camp. Prioritized phase one projects were listed as:

Restoration of buildings at American Camp

Reconstruction of American Camp picket fence

Move temporary headquarters to American Camp

Construct a maintenance facility at American Camp

Develop water and sewer systems and bury powerlines

Develop interpretive markers along Jakle's Lagoon trail

Develop and install brochures and dispensers for island bound ferries

Install park mileage road signs in Friday Harbor

Reconstruct parade ground fence at English Camp

Research and replant formal garden

Upgrade existing roads and parking at English Camp

Construct Bell Point nature trail with interpretive trail exhibits and markers

All other projects fell into the second and third five-year phases. Total cost estimate for all the projects proposed for development: $2,033,000.00.

Development of campsites at American Camp was a major planning item in the new GMP that carried over from initial park planning, but shortly thereafter, was dropped for two reasons. First, the public on the whole viewed the proposal unfavorably. The primary reasons for their lack of support on this issue were a dislike of anything that might aid or precipitate increased visitation to the island, but more importantly was the fear that the campsites would hurt the business of two privately owned and operated campgrounds on the island. Secondly, the park could not accurately determine that adequate potable water supplies existed at the camp to support large-scale camping, especially during the summer seasons. These two factors combined to end serious planning attempts for campsites.

Public comment on the 1979 GMP raised one interesting point: a large percentage of those who commented on the plan and its ALTernatives remembered initial development planning for the park and items identified in the 1967 Master Plan, most specifically the fact that the headquarters had not been moved into Friday Harbor as proposed. One letter stated that the park should complete one master plan before starting a new one.

One of the largest gaps in the park's written record is the period of Zachwieja's superintendency. Aside from planning documents and correspondence for the new GMP, little written evidence exists, including any references to where or why Zachwieja left the park. In interpretation, Zachwieja did hire Patricia Milliren, the park's first full time park ranger dedicated to interpretation. It was under Milliren's direction that living history programming at the park began (see Chapter V).

Frank Hastings, 1980-1984

Frank Hastings served as superintendent of Navajo National Monument in Arizona for eight years prior to his transfer to San Juan in 1980. Upon arrival at the park, he immediately set about trying to improve the standing of the park in the community. When he arrived, the park had tentative relations with the local public at best. Public relations existed only when the park implemented programs that had an impact on local residents, which often meant that relations existed when a conflict arose. Superintendent Hastings began by getting involved in local clubs and encouraging the same of his staff. In 1981, Hastings was elected to the Board of Directors of the Friday Harbor Chamber of Commerce. [15] By giving the park an active role in the community, Hastings also laid the groundwork to reopen negotiations for the county road closure at American Camp.

With a by-pass road already constructed, Hastings worked to convince the community that removal of the old road was necessary for the protection and interpretation of the park. Superintendent Hastings took steps to make sure that people understood clearly the park's goals and reasoning for the move by holding meetings, hoping to gain support for the closure prior to requesting specific action. The move would not happen during Hastings term, but he continued to push for that as his primary goal.

In 1981, park administration spent a great deal of time with internal personnel matters. A charge of harassment by one employee against another developed into a second, formal charge of discrimination by park management as a whole. The second charge alleged that the park, under Hastings' management, had retaliated against the employee who filed the original complaint. The Seattle and Washington, D.C. (WASO) support offices investigated the charge. WASO investigators who came to the park to interview staff left behind a negative atmosphere. Park staff was troubled by the way the investigators handled the interviews, which were reported as "interrogations" in the superintendent's annual report. [16] Park relations with the regional office and WASO were strained during this period, with distrust and some hostility evident in written documents. Resolution of the charge is not available in park records due to the confidential nature of the investigations. What is known is that six months after the investigation, when the 1981 annual report was written, no decision had been reached on the issue and the investigation was not mentioned again.

Building restorations continued under Hastings, starting with the English Camp Hospital in 1981. The building was stabilized, re-roofed, and painted. In 1983, restoration work on the American Camp laundress' quarters began, including stabilization and construction of a new chimney. In an effort to remove all non-historic structures in the park, the Katz (Whitridge) house, located just off the American Camp by-pass road, was put up for auction twice, with no bidders. In 1983, the park donated the structure to the rural fire district, which destroyed the building in a training exercise.

Volunteers became increasingly important to the park during Hastings' term. One realm of volunteer participation came in the form of ferry contacts. Volunteers on board regular ferry runs made contact with potential visitors to the island, informing them about the park, how to get there, and what programs were available to them. In 1981, the volunteers contacted approximately 8,300 people. [17]

Maintenance received help in the form of Young Adult Conservation Corps (YACC) crews, who helped with the installation of split-rail fencing, clearing of brush, and the installation of insulation and siding for the maintenance facility. The crew also completed work on the historic garden and stabilization of the historic maple tree at English Camp.

Fire continued to be an issue at the park. Beach fires left unattended by picnickers totaled 10 in 1980, 9 in 1981, and 10 in 1982. In most cases, park personnel contained the fires. In 1981, a fire caused by an eagle contacting a power line burned 79 acres at American Camp. Three fire companies responded as well as the Washington State Department of Natural Resources. In a separate incident, fire destroyed the maintenance shop, the cause of which was attributed to poor housekeeping by park staff.

Park staff completed the first fire management plan and Randy Richter of the U.S. Forest Service completed a fuels assessment/treatment plan for the park. Fire fighting equipment was also purchased, including a pumper truck.

Interpretation continued with a mix of film programs and guided walks conducted by seasonal rangers and volunteers. However, in 1981, the living history program was suspended due to "inadequacies in the park program." [18] What the inadequacies were is not clear. Since the park continued to have personnel conflicts and staff time spent resolving other issues, the time to invest in a regular or expanded living history program may have been limited.

In early 1985, the regional office began a management review for the park in the form of a study team to review and make recommendations to improve park management. Deputy Regional Director Bill Briggle wrote to Superintendent Hastings that "there have been many problems at San Juan Island with which you have effectively dealt...". But morale was apparently low and the study team was designed to "reaffirm the Service's commitment" at the park. [19] Superintendent Hastings retired from the National Park Service shortly after the study team was initiated.

Richard Hoffman, 1985-1991

Superintendent Hoffman came to San Juan from the Pacific Northwest Regional Office in Seattle. Hoffman was interested in moving out of PNRO and back to a park, so he actively campaigned to be the new superintendent of San Juan. He was placed there on a probationary term as superintendent by acting Regional Director Bill Briggle. Superintendent Hoffman remembers his number one priority was survival as the park's superintendent and spent his first year dealing with personnel issues. [20] Within two years the park had almost an entirely new staff.

Hoffman set the following objectives for park management: to develop reachable goals in park development and operations; to instill a sense of ownership in park staff; and attempt to build more favorable community relations for the park. [21] Under those objectives, the park achieved a few important moves: closure of the county road through American Camp and leasing office space in Friday Harbor.

During Hoffman's term, the park upgraded internally. For example, computer systems were installed to facilitate better transmission of general reporting requirements and payroll data. From 1986-88, Hoffman served as the NPS representative for Ebey's Landing National Historical Reserve on Whidbey Island, giving him added tasks and requiring him to be out of the office on a regular basis. Hoffman established a strong working relationship between himself, Chief Ranger Steve Gobat, and Administrative Officer Diane Joy during this time. This relationship assisted park management when Hoffman was later diagnosed with cancer. His illness took him out of the office for significant periods of time and would eventually lead to his retirement from the NPS in 1991.

In 1985, the park received assistance from PNRO in cleaning up the in-park curatorial collection. Items were catalogued, the English Camp cemetery headstones examined, and the decision made to replace the one wooden one. All the Crook family items were finally removed in 1987 and the park leased storage space in town for its museum collection.

Under Hoffman's tenure, the English Camp formal garden fence was reconstructed, and final restoration of the garden was completed in 1986. The garden program was one of several events completed in honor of the park's twentieth anniversary, which the park called SAJH 20. Other events included a living history Christmas party at English Camp and a Founder's Day picnic. Ranger Detlef Wieck was nominated for and received the regional Freeman Tilden award for interpretation in 1990 for his efforts in developing the volunteer program at the park.

Road Relocation

It was under Hoffman's management that the county road at American Camp was finally closed. Ranger Steve Gobat remembers planning the road restoration quickly, so the county couldn't change its mind in the face of any potential public outcry. [22] In January 1990, the county vacated 1.3 miles of road. The park closed the road April 9th and by May the restoration work had been completed.

For the most part, the road exchange and removal went smoothly. Some islanders were never going to accept the move as necessary and better for the park. Public opinion succeeded in delaying the move for 16 years. Whatever anger and disagreement was generated by the move, however, dispelled fairly quickly.

A pilot planting project was started at American Camp in 1986, to test the feasibility of replanting trees in the northwest area of the camp. Another American Camp change was the addition of horseback riding. Started by a public request, Hoffman designated specific areas, instituted a permit system, and got clearance from the regional office to allow local horse riding enthusiasts to ride at the park.

In an effort to attract seasonal volunteers to the park, a trailer pad was constructed in 1988 at American Camp. The problem of affordable, available seasonal housing has always been a problem. This space allowed volunteers to hook up trailers or motor homes while working at the camp.

Friday Harbor Administrative Office

In 1984, the park located appropriate office space in Friday Harbor for a contact station. Returning park headquarters to Friday Harbor gave the park heightened visibility not only to potential visitors getting off ferries, but to the overall community. Following the move to American Camp, it had taken seven years for GSA to find an appropriate space for the park to lease.

A New Maintenance Facility

In 1990, a new maintenance facility was constructed to replace the original shop destroyed by fire. The park went six years between the fire and the construction of a new building. In the interim, the maintenance crew operated out of the Jameson house acquired during lands acquisitions for English Camp, and which lacked a hot water heater and had a leaky basement. [23] The Jameson house was sold and moved off park property prior to construction of the new building.

Richard Hoffman retired from the NPS in 1991 in order to focus on his health. The incoming superintendent had nearly 20 years of experience as a NPS superintendent to help guide San Juan's future.

Robert Scott, 1991 to Present

Superintendent Scott arrived at San Juan in 1991 from Craters of the Moon National Monument in Idaho. Scott's first year at the park saw a visitation record: 359,168 visitors. He has continued to maintain and improve the park's community relations through involvement in service clubs and maintaining relationships with outside organizations. He also worked to establish a formal natural resource management program through the creation of a new resource management/law enforcement position, whose job tasks were previously a collateral duty of the chief ranger. Since then, the number of resource management projects identified at the park has increased from 18 to 83. [24]

Scott's first order of business was overseeing building construction and maintenance. The maintenance facility at English Camp was nearing completion and the visitor center at American Camp had to be repaired from winter storm damage, including a new roof and some dry wall, as a result of a falling tree. Scott worked to improve park infrastructure, getting new phone lines installed in Friday Harbor, American Camp, and the maintenance shop at English Camp. Park staff also worked to maintain log barriers placed on South Beach as a method of keeping vehicles off of the beach and prairie. In 1992, the American Camp parking lot, which was small and accessed by one narrow lane, was redesigned. The lot was expanded and the traffic pattern altered for better access. The entrance road was also widened.

|

| Artifacts from the park collection on display in the American Camp exhibit, completed in 1996. |

In 1992, exhibits from the English Camp Barracks were moved into the Friday Harbor office. Regional curatorial funds were secured to continue cataloging archaeological artifacts at University of Washington and University of Idaho. In 1993, the park entered into a cooperative agreement with North Cascades National Park's Marblemount facility for storage of the park's historic artifacts. This arrangement became necessary when University of Idaho's storage became unavailable. The park's prehistoric artifact collection continues to be stored at the University of Washington's Burke Museum in Seattle.

At American Camp, the historic parade ground fence was rebuilt. Replacement of the fence was designed as a method of defining the historic landscape of the camp. Monies to purchase supplies came from a cooperating association special projects grant. New exhibits showcasing items from the park's archaeological collection were designed and built by park staff in 1996.

Interpretation has continued to utilize living history demonstrations when feasible. It has relied heavily on self-guided trails at American Camp and guided walks when staff is available. Park staff has continued involvement in the town's annual Memorial Day and 4th of July parades and the Pig War Barbeque. A long-range interpretive plan is scheduled for completion in 1999. The interpretation program received a grant from the National Parks Foundation in 1996 to build a travelling trunk exhibit and educational outreach program. Focusing primarily on school groups, the grant will enable the park to take its interpretive message beyond the park boundaries.

Recent facility planning under Scott includes the installation of three new outdoor toilets, one each at English Camp, South Beach, and 4th of July Beach. These will help accommodate the increasing numbers of visitors. Scott has initiated planning for the adaptive reuse of the Crook House to provide critically needed seasonal housing. In addition, Scott has initiated planning and coordination to complete controlled burns at American Camp and English Camp to aid in the restoration and regeneration of native plant species.

Scott has had to deal with budget cuts and even a budget shortfall during his administration. Normal staffing levels for the park include 6 seasonals for interpretation and 4 in maintenance. But since 1994, the park has typically only had two to three seasonals total, and getting those has been a challenge. In 1997, there were no summer interpretive seasonals, forcing the park to rely on volunteers to handle the summer interpretation programs. The park must continue to rely on volunteer efforts and work to increase the number and variety of non-personnel visitor services.

Superintendent Scott has announced his plans to retire in late 1998. Following the limited staffing of recent summer seasons, the park has been identified as one of several parks in line to possibly receive a future base funding increase. With a new GMP slated for 2000, the replacement of Superintendent Scott, and a potential base funding increase, the park is reaching another time of transition that will greatly shape its next decade.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

sajh/adhi/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 19-Jan-2003