|

San Juan Island

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 5:

Resource Management

San Juan Island N.H.P. is described as a microcosm of the NPS, with its important cultural, natural, and recreational resources and issues. The most constant management concern has been historic structures. In addition, the park is rich in archaeological sites and has a diverse museum collection. The park also has a rich mixture of natural resources with a wide variety of flora and faunal species, set within environments ranging from rock bluffs to prairie, and forest to beach.

Historic Resource Study

In 1972, Denver Service Center historian Erwin Thompson completed the Historic Resource Study for San Juan Island N.H.P. Thompson's study included a social/political survey of the island's historic events, as well as a survey of the architectural history of the two military camps. His social review also details the interactions of the Royal Marines and U. S. Army soldiers stationed on the island. Thompson's research is an excellent source of interpretive material for the park regarding everyday life and activities at both English and American Camps.

Thompson examined records documenting the twelve-year occupation by the U.S. Army and Royal Marines for information regarding the construction of buildings at the sites and their uses. Thompson was looking for any information to assist in rehabilitation and restoration efforts. In addition, Thompson researched buildings on the island rumored to be from the camps, assessed their authenticity, and provided recommendations for their potential use.

Thompson's research indicates the Royal Marines built at least 37 buildings at English Camp. Use and location can be determined for most of the buildings. In addition, archaeological sites exist which seem to be from historic military construction, but specific use is unknown. Thompson speculated that these sites could be from temporary structures that were replaced during the first few years of occupation. The most useful information regarding historic structures at English Camp comes from surveys completed by the U.S. Army after acceptance of the site in 1872. These surveys indicate which structures were fairly new construction and what the various uses of the buildings were.

The Blockhouse, Barracks, Commissary, and Hospital structures remain at English Camp today. The small cemetery on Young Hill also provides a poignant reminder of the British military encampment. Also visible is the stonework foundation of the officers' quarters, stone steps up the hillside, and the stonework remains of what was probably a bake oven. For a complete listing and identification of sites, refer to the historic base map on page 89.

Historic Base Maps

|

| San Juan Island (click for a larger image) |

|

| American Camp (click for a larger image) |

|

| British Camp (click for a larger image) |

|

| San Juan Town (click for a larger image) |

Thompson's research indicated that the United States Army built no less than 34 structures at American Camp during the 12-year occupation. Structures included the blockhouse/guardhouse, enlisted men and officers' quarters, a bake house, barracks, messroom and kitchen, two hospitals, storehouses, a blacksmith shop, granary, carpenter shop, school and reading room, bath house, telegraph office, shoemaker shop, cemetery, roothouses, the flagstaff, and the redoubt, among others. [1] For a complete listing and identification of sites, refer to the historic base map on page 90 for American Camp. Two structures, the Officers' Quarters and Laundress' Quarters, survived and have undergone restoration for the interpretive program.

Historic Structures Report: Architectural Data

In 1977, NPS architect Harold La Fleur, Jr. completed the architectural report for the Officers' Quarters and Landress' Quarters at American Camp, and the Hospital at English Camp. The study compared Thompson's historical research findings with data gathered by the University of Idaho archaeological field school under the direction of Dr. Roderick Sprague. Armed with this new data, La Fleur confirmed that the McRae and Warbass houses were indeed American Camp structures.

Both American Camp buildings had undergone substantial remodeling and additions over the years and it took the archaeological work of the University of Idaho to settle the placement and authenticity of the structures. By examining the structural evidence in relation to the buildings, it was determined that the McRae house was HS 11, Officers' Quarters. By the same methods the debate over what function the Warbass house served was settled. The field school had excavated an almost complete foundation for HS 6, Laundress' Quarters, which Sprague felt was an 80% match to the Warbass structure. [2]

|

| The English Camp Cemetery. |

La Fleur's report provided the necessary architectural data, floor plans, and recommendations for the park to move ahead with restoration of the three structures.

Blockhouse

Standing on the edge of Garrison Bay, the English Camp Blockhouse is a well-known park icon. Probably used as a guardhouse, the structure is two-storied and at one time had a wood stove and a porch. The log base, exposed to the Garrison Bay tides and increased erosion, creates additional deterioration factors for maintenance. When the NPS took possession of the structure, there was evidence that the building had undergone some additional construction and ALTeration following the historic period, most likely completed by the Crook family as they adapted the building to suit their needs.

During 1970, the Blockhouse was the first restoration undertaken by the NPS. The structure was stabilized and leveled. Logs at the base of the Blockhouse, deteriorated from water exposure, were replaced. The roof was replaced and the building whitewashed. Most of the structure's base-logs were replaced again in 1995 by a multi-park crew.

Barracks

The Barracks structure has seen the most restoration and the most use. It was also in very poor condition and the structure underwent a major overhaul in 1970. The building has received periodic whitewashing and stabilization treatment over the years.

The Barracks has always served as the visitor station for English Camp. Staffed during the summer season and during special occasions by NPS staff and volunteers, the structure has been the site of regular slide presentations, exhibits on the camp and on site archaeology, and special events and lectures.

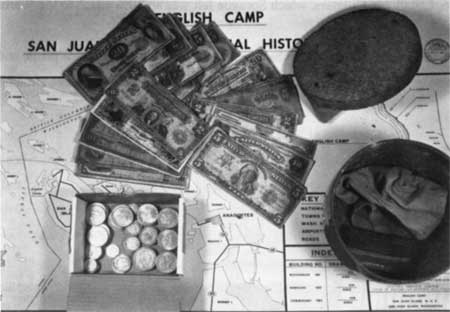

As a side note, during restoration of the Barracks, a small can of coins and valuables was discovered under the roof. Rhoda Anderson had informed Carl Stoddard that she knew her father had stashed some money in the Barracks during the time they were living there, but she never knew where. [3] Stoddard had told the construction crew to be on the look out for the stash, which was found and returned to Mrs. Anderson in a small ceremony.

|

| The coin and cash found in the Barracks, later given to Mrs. Rhoda Anderson. |

|

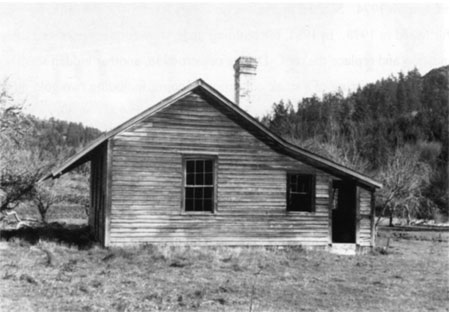

| The restored Barracks building. |

Commissary

Like the Barracks and Blockhouse, the Commissary is one of the three original structures to have survived at English Camp. Its condition matched the Barracks structure. Extensive restoration work to level and stabilize the building was carried out between 1971 and 1972.

Hospital

The Hospital is the one structure at English Camp that had been moved to another location, three miles away to the Peter Lawson farm. It was later identified by the NPS and returned to the site for restoration.

Howard Lawson, heir to the Lawson farm, began negotiations with the NPS for the donation of the Hospital building around 1971. In 1972, he sold the property to James Mathis, who donated the structure in 1973. The structure was moved back to English Camp in 1974. Studied by Harold La Fleur, Jr. in 1977, the building's exterior was refurbished in 1978. In 1981, the building underwent further restoration to stabilize the foundation and replace the roof. During construction, another hidden stash was found, this time consisting of a small collection of coins, including two gold pieces, a diamond ring, and a watch. The items were discovered above a window. Three individuals claimed the find, which was turned over to the U.S. solicitor's office. It was later determined that Howard Lawson was the rightful claimant, since he had inherited the building prior to its donation.

In 1990, a Historic Furnishings Report for the English Camp Hospital was produced under contract for the NPS. Prepared by historian Florence K. Lentz, with Dr. William Woodward and Bridget E. J. Spiers, the document chronicles the medical history of the British Royal Marines during the late nineteenth century, drawing from studies regarding similar naval hospitals, and a history of the medical services at English Camp. The report determines that not enough information is known specifically about English Camp's hospital to refurbish it as a restoration. However, the report does offer other treatment ALTernatives.

|

| The restored Commissary. |

|

| The Hospital after being moved back to English Camp, prior to restoration. |

Other Royal Marine medical facilities from the late nineteenth century around the region are well documented through inventories and journals, specifically one in EsquimALT, British Columbia, Canada. One ALTernative would be for the park to restore the interior to represent a typical Royal Marine medical facility and interpret it as such. Another option was simply to restore the interior for use as an interpretive facility, where the interior would undergo general rehabilitation but not include specific structural furnishings. The report ends by offering potential opportunities for interpreting late 19th century British naval medicine.

The Crook House

Historical Architect Laurin Huffman is right on target when he states that management planning for the Crook House has been inconsistent over the years. During establishment of the park, the NPS promised the island community some interpretation of Jim Crook's life and role in preserving English Camp. However, planning since initial development relegated that theme to a minor role. As a result, the house has been looked on more as an intrusion of the historic setting than as an integral part of it. Upper management in the regional office considered getting rid of the house ALTogether; the cultural resource division in Seattle has long supported the idea of making the house a visitor contact station. [4] From a "historic scene" perspective, this is not a popular move since the house post-dates the military occupation. The house itself was recently determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places through draft documentation completed by Florence Lentz. But removal would be even less popular in terms of public relations. Local island history looks favorably on Jim Crook, not only in his association with English Camp but as an inventor. Regional Historical Architect Huffman recommended taking steps to "remove" the impact of the house on the historic setting of English Camp in a less drastic way than demolition: muted gray paints replaced the original white color of the house and landscaping was used to visually screen the house from the rest of the site. [5]

|

| The Crook House, painted its original white, overlooking the parade ground. |

Until 1986-87, the structure was used to store park collections and what remained of Crook's large farm implements and machinery. With the final removal of Crook materials to the San Juan County Historical Society and acquisition of ALTernate storage space, the house has remained largely unused.

There have been many ideas presented for the adaptive reuse of the Crook House over the years, including seasonal housing, administrative offices, or a visitor center with exhibits. A Historic Structures Report produced in 1984 details the Crook family settlement of the property and the life of James, who inherited the site from his father. The study also summarizes the architectural stylings and preservation needs of the house. The report stated that the house needed a top-to-bottom rehabilitation, done in such a manner as to minimally ALTer the structure's historical integrity while bringing the building up to code for modern day use.

Suggestions for the reuse of the house included: recommended studies to incorporate the house into the historic scene; utilization of the structure as a visitor center, with a lobby, sales counter, and exhibit space; curatorial storage; and space for a ranger station, with an office, break room, and employee-use-only restroom.

None of the work recommended in the structures report was implemented. In 1991, studies were initiated to determine the practicality of adapting the house for use as seasonal housing. The availability of affordable housing for seasonal employees has always been an issue for the park. Ellen Gage, historical architect stationed at Olympic National Park, completed design plans for adaptive reuse of the house for seasonal quarters. Funding is currently being sought to begin implementation of the design.

The Redoubt

In recent years, the Redoubt has undergone study to assess erosion within the structure and the effects of decades of rabbit burrowing in and around it. The structure is a unique example of fortification building from the Civil War era, and is earning interest from military historians. Most structures engineered by the U.S. Army during the 1860s were subjected to actual wartime use, but this Redoubt never saw such action.

Under contract with the NPS, Dale E. Floyd, senior historian for consulting firm CEHP Incorporated, completed a report titled Comparative Analysis, American Camp Fortifications, San Juan Island National Historical Park. Finished in 1996, the report analyzed the Redoubt in relation to typical U.S Army fortifications built during the mid- to late 1800s. The report provides park managers with comparative analytical information about the structure and includes references for the park to utilize in its management and stabilization planning activities. In addition, the Redoubt was surveyed and mapped with one-foot contours to establish a baseline for future monitoring.

Officers' Quarters

Originally there were three officers' quarters at American Camp, one of which was occupied by Captain Pickett. A number of structures located elsewhere on the island were rumored to be that structure. In 1972, Thompson ruled out two of those structures. One was the Warbass house, which was determined to be a historic American Camp structure, but not Pickett's. Another was a house located near Friday Harbor, which Thompson surmised could be a structure from the camp. Even if true, the severe deterioration of the structure prevented a move to American Camp. [6] Lastly, he considered the McRae house, which stood about 900 feet west of where Thompson calculated all the officers' quarters to have been built.

During historic structures research, the McRae house was treated as an original officers' quarters structure, with some modifications. Later research and archaeological excavation confirmed early assessments of the building's identity as an original American Camp structure.

In 1981, the structure underwent restoration, which returned the exterior of the building to its original state. Post-historic remodeling has ALTered the inside of the building, making interior restoration difficult; further research will be necessary if the park hopes to restore the interior of the Officers' Quarters and make interpretive use of the space. [7]

|

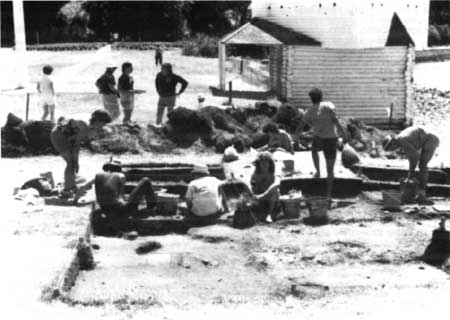

| The Officers' Quarters, 1970, (back, right) with University of Idaho field school excavations in progress. |

Laundress' Quarters

Originally called the Warbass House, Thompson initially thought this structure to be the "Pickett" house or an officers' quarters. He determined the structure to be from American Camp, and like the McRae house it had seen additions and changes over the years. He determined that the structure was not an officers' quarters, for the original structure was too small.

Warbass had moved the structure to his property around 1875. Thompson guessed by its size that it was probably the adjutant's quarters or the telegraph office. The structure was later determined to be one of the laundress' quarters and matched structural evidence uncovered by the University of Idaho field school.

The last of the six historic structures to undergo restoration, work on the building began in 1983. It was also in the worst shape of all six and was badly deteriorated. A contract was awarded to NPS. Williamsport Preservation Training Center to undertake the work. Superintendent Hastings was extremely pleased with the results, stating that the project came in under budget and ahead of schedule. [8]

Robert's Plaque and other features

On a stone boulder next to the Redoubt, a bronze plaque honors Lt. Henry Martyn Robert, U.S. Army engineer, who was responsible for the Redoubt design. It had been mounted in 1942 by the Governor Isaac Stevens chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. Formal dedication ceremonies were held in 1947. [9] The group honored Robert for his work designing the Redoubt, but also for his later military career, including Robert's Rules of Order, his most well-known accomplishment.

At English Camp, next to the formal garden, is one of the oldest bigleaf maple trees in the Northwest. In 1997 in was dated at 324 years of age. The maple is managed as a historic tree. Recently, the remaining trees from the Crook family orchard have come under the umbrella of historic tree consideration as well.

|

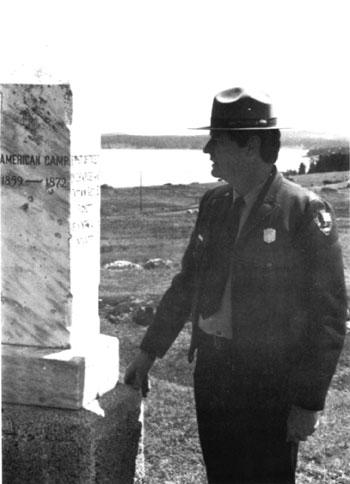

| The American Camp Monument at its previous Redoubt location, with Superintendent Carl Stoddard |

The two marble monuments erected in 1904 by the University of Washington State Historical Society still stand at both camps. In September 1989, the monuments were cleaned of lichens and stains under the supervision of the regional curator. In 1992, the American Camp monument was moved from its original location at the Redoubt to its current home next to the American Camp headquarters.

Historic Landscapes

Much consideration and planning has gone into the historic landscapes at San Juan Island N.H.P. American Camp and English Camp present very different landscapes to the visitor, with varying degrees of success. Historic landscape issues at the park cover a wide range of issues, from maintenance of the formal garden at English Camp to development and maintenance of all roads and trails. In short, the historic landscape is intended to convey a sense of the historical period and events to the visitor.

English Camp Formal Garden

Since the early 1970s, work restoring the formal garden at English Camp has been maintained almost solely through volunteer efforts. In March 1982, Landscape Architect Carol Meadowcroft produced a report titled Reconstruction of Historic Formal Garden at English Camp. Meadowcroft's report considers the historical time frame of English Camp in relation to the history of English formal gardening around the world. Meadowcroft researched existing documentation of the garden, planted under Captain Delacombe, and reviewed the only known historical photograph of the garden. Combining what is known about the garden from the historical record with historical trends in English gardening, Meadowcroft developed a restoration plan and maintenance program for the garden.

Meadowcroft defined the formal garden as a part of the "Gardenesque" period of English gardening. This style entailed the use of geometric patterns within a natural setting. The formal garden at English Camp had replaced an earlier vegetable garden and was established during the formal construction of officers' quarters on the hillside. The Gardenesque style is also reflected in the pathways through the garden and up the hillside, forming a transition between parade ground and residential area. [10]

|

| The only historic photograph to show the formal garden. |

|

| Volunteers at work in the garden. |

For the 1976 American Bicentennial, the garden was reestablished in a 70-foot circular design matching the only historical photograph of the garden. The park utilized evergreen shrubs and flowering plants. Until Meadowcroft's report, no research had been done on what type of flowering plants and shrubbery were available to the marines during the late 1860s. Meadowcroft researched archives on Vancouver Island as well as the U.S. National Archives, but did not find much. However, research of newspaper advertisements of the day in the Daily British Colonist out of Victoria provides an indication of what plants were being sold in the area. From this research, Meadowcroft developed a list of plant materials to be utilized in the garden. Consideration was given to substituting perennials as a time and cost-saving measure for the park.

The report provides a planting plan for the garden as well as future maintenance and plant rotation recommendations. Utilizing Gardenesque methods, Meadowcroft divided the circular garden into beds, with individual types of flowering plants massed in each bed. The historic photograph indicates that the flowering plants were planted in semicircular rows. Taller plants are programmed in the interior beds with lower growing plants in outer beds. Beds are lined with common boxwood and the central planting bordered by caladiums.

Meadowcroft recommended the park consider the seasons and blooming times of the flowers chosen for the garden to maximize length of time the beds show color, and try to program the best mix of colors during peak visitation times. In addition to providing the park a listing of annuals and perennials for use in the garden, the appendices also list where research was completed and where future research needed to be done. Meadowcroft's research is the primary reference tool for current volunteer efforts to maintain the garden.

Historic Landscapes of San Juan Island N.H.P.

In 1984, James K. Agee, a forest biologist with University of Washington Cooperative Park Studies Unit in Seattle, completed the report entitled Historic Landscapes of San Juan Island N.H.P. under an agreement with the park. In Agee's report, he examines the historic landscapes at both camps under four time periods: prehistoric, historic, post-historic, and park period. The research and planning in his report was completed as part of a regional interdisciplinary study team considering resource management issues at the park, the subject of a later discussion in this chapter.

Agee offers information regarding species types prevalent at both camp sites during the four time periods as well as the impact of historic land use patterns. Through historic photographs and field research, Agee determined what constituted the historic landscapes the park would try to reestablish and preserve.

At English Camp, Agee identified two major landscape elements: Garry oak and woodland, coniferous forest. The forests at English Camp were burned during the 1700s and had successfully regenerated. The forests also were subjected to some burning and cutting by native peoples inhabiting the site, and later by the Royal Marines. However, the most alteration came during the post-historic period, when the Crook family and others began agricultural production and timber harvesting on Young Hill during the period 1880-1920s. [11]

By the time of park creation, successful forest regeneration had already begun. Agee states that in 1983, the major areas of timber cutting and agricultural usage (roughly 34 acres) had approximately 12,000 stems per acre. Agee determined that the historic setting at English Camp was not that far removed from present landscapes. The report recommended thinning over the next 20 to 30 years, which would accelerate the growth of the remaining tree population. Red cedar, Douglas fir, alder, and grand fir would also need to be planted in open areas. Management was presented with a choice of time periods to represent through the wooded landscape: limited settlement of the early 1860s or full-scale construction completed by 1872. They opted for the earlier time period.

Agee's report found American Camp considerably altered from its historic state, so much so that it was difficult to ascertain conclusively the nature of the prehistoric landscape. To try and determine what plant types may have existed at the site prior to European settlement, Agee examined soil types. Soils ranged from glacier till and sandy loam, which support grasses and a few trees, to soils that support forest stands. Consideration was also given to climate and weather exposure. These, coupled with historical descriptions of the site, led Agee to determine five areas of typical landscape types: dry grass, woodland, open Douglas fir type, mixed pine type, and western hemlock.

From this research, the report suggests regeneration of mixed pine forest areas and provides information on obtaining seedlings and methods of planting. Agee suggests further planning be done to determine which planting methods and maintenance schedule to utilize.

To summarize, Agee's report offers programming goals for the park's historic landscapes. At English Camp, programming should erase the evidence of agricultural operations. At American Camp, visitors should be able to see the densely forested area chosen by Colonel Casey for the third campsite.

Consideration For Management of Grassland Vegetation at San Juan Island N.H.P.

Jim Romo, an Oregon State University research associate in the Department of Rangeland Resources, produced the above-noted report in July 1985. The report was designed to help management determine its objectives in managing the grasslands at American Camp, specifically exotic plant species.

The report offers information on what plants are weeds at American Camp. It offers specific recommendations on controlling Tansy Ragwort and Canadian thistle, the two most troublesome weeds at the site. The report also offers some experimental control options. The report makes it clear that many factors have been at work on the prairie of American Camp to cause the introduction of exotics. Romo states the park needs to treat the source of the problem, not the result, if it is to succeed in maintaining the prairie's historic nature. Park staff continue to wrestle with the appropriate way to handle exotic species at American Camp, and recently have begun to consider the feasibility of implementing controlled burning to regenerate native plant growth. Currently, however, old-fashioned weed pulling is the method most often employed to combat exotic species.

Historic Landscape Study

This study was completed by Pacific Northwest Region historical landscape architect Cathy Gilbert between 1985 and 1987. The report starts by clearly stating it is a technical document designed to collect, present, and evaluate documentary and field survey evidence, and propose appropriate management options for historic landscapes at the park. The document was not intended as a decision document, which requires public meetings, an environmental impact assessment, and consultation under Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act.

For each camp, the report provides a historical and archaeological overview and a summary of current landscape conditions. In addition, surveys revealed new structural remnant findings on officers' hill at English Camp, and research results presented.

The report responds to a very important question: what should the visitor to San Juan Island N.H.P. experience at each of these camps? In response to that question, a series of design recommendations for future planning and a number of design alternatives for American Camp (4) and English Camp (3) are offered. The goals of the design recommendations were defined as the stabilization and preservation of resources, removal of non-historic components, and enhancement of historic features that are ill-defined or can be verified through archaeology. The design recommendations were presented in five management areas: buildings and foundations; access and circulation; plant materials; special features, site details and materials; and maintenance and management concepts. Each of these five areas were considered for each camp.

Using the design recommendations, Gilbert developed design alternatives for each camp, each providing a different level of design treatment for each historic setting and varying degrees of opportunity for interpretation and visitor experiences.

For American Camp, the key elements of the design alternatives centered on defining the historic landscape for better visitor understanding. The alternatives provided a huge range of options for park managers to consider. When the report was completed, the regional cultural resource division in Seattle developed a fifth alternative for American Camp, which was completed in 1990. This became the preferred alternative and called for:

- A new visitor center at the site

- New parking and informal picnic areas

- Existing historic buildings used for interpretive exhibits

- Completion of a historic structures report for the Redoubt

- New trailhead and parking at the Redoubt

- Remove the county road

- Creation of a series of interpretive trails

- Assist San Juan County in defining the military road between American and English Camps

- Reestablish the historic picket fence and boardwalk

- Mark non-extant buildings

- Reestablish portions of forest northwest of the campsite

- Reestablish the American Camp garden

- Monitor rabbit populations

- Bellevue farm: develop a loop trail, reestablish historic fencing, mark non-extant buildings

- San Juan Town: develop trail loop, identify and mark non-extant structures

- American Camp cemetery: sign and mark along interpretive trail

- Spring Camp: sign and mark along interpretive trail

The preferred alternative treatments were designed to provide visitors with an understanding of the size and scope of the historic scene, the county road would no longer be an intrusion, and the Redoubt would be stabilized with a new trailhead and parking. Adjacent sites would be tied to the camp through a trail system and interpretive opportunities would be expanded. To fulfill these recommended treatments, the park would require an expanded staff and a budget increase.

For English Camp, Gilbert's design alternatives centered on defining the role of the Crook House and the stabilization of structural wall remnants along the hillside. Again, the regional cultural resource division examined the options presented and developed a preferred, fourth alternative. Under the new preferred alternative, the focus was placed on identification and enhancement of the historic scene, with the Crook House being converted to seasonal quarters. The preferred alternative called for:

- Modification and improvement of the parking lot

- Rehabilitate and use the Crook House as seasonal quarters, using landscape planting to screen the house from the view of the camp site

- Comprehensive archaeological investigation of hillside remnants

- Stabilization and preservation of the masonry ruin and other historic features

- Selective clearing of the forest on Officers' Hill and on the Northeast slope to reestablish historic vistas and viewsheds, as well as clearing to protect and stabilize remnant features along the hillside

- Identify and mark all non-extant buildings through stone foundation footings and ghosting structures

- Reconstruction of the bird house on Officers' Hill

- Maintenance of the formal garden

- Reestablishment of northeast section of historic fencing to establish the historic site boundary

- Stabilize the cemetery, correcting drainage problems, maintain gravesites, recording the headstone information and possibly replacing if severe deterioration occurs

Gilbert's study presented a wide variety of design options, ranging from no action to full reconstruction. All of the design elements and recommendations in the study were developed with the goal of enhancing the interpretive and environmental context for the site, providing visitors with a greater understanding of the scale and character of the historic landscapes. [12] In summary, the report noted that implementation of the preferred alternatives at either site would require staff and budget increases.

Pilot Planting Project

In 1986, six half-acre quadrants at American Camp were replanted with 100 Douglas fir seedlings per each quadrant. The plantings were an experiment to test methods of replanting around the American Camp area to determine the feasibility of initiating a larger scale replanting program to restore native species and forest that existed during the historic period.

On each quadrant, three different protective screens were tested. Divided into groups of twenty-five, three sets had varying degrees of screen protection while the fourth had no protection. Different levels of herbicides were tested for controlling grass and weeds around the seedlings.

James F. Milestone, Pacific Northwest Regional Office natural resource management trainee, reported on the progress of the trees in September of 1986. Overall, in eight months they lost 116 trees out of 600. The natural decline in rabbits that had occurred during the early 1980s had opened the door for better grass and seedling production. However, it also meant that the Townsend vole did better as well, feeding on the young seedlings. One hundred eleven trees were attacked by voles, but Milestone reported that vole attacks did not equate to mortality.

What did kill the trees was water saturation of roots during winter storms and drought during the summer. Also, those seedlings planted in areas treated with herbicides had a low mortality rate not having to compete with grasses and weeds. In the end, the trees with a hard protective screen planted in a grass-free space had the highest success rate.

Milestone recommended future plantings using a six-foot, grass-free perimeter with hard protective screens to protect seedlings from voles. He also recommended that prior to replanting, planning be given to match seedling type to available soil drainage in order to prevent deaths due to saturation. He provided an outline for future planting efforts. In short, pilot planting efforts lost approximately one-sixth of the starts, but produced the data necessary to continue reestablishment of forested areas around the camp.

Archaeological Resources

The first recorded archaeological work done on the island was completed by Harlan Smith in the 1890s as a part of the Jesup Expedition, sponsored by the American Museum of Natural History. [13] In the late 1940s and in 1950-51, the University of Washington completed field excavations of known prehistoric long house sites at English Camp and on Cattle Point near American Camp. The findings of these excavations have not been located. Throughout the first half of the 20th century, archaeological sites (both prehistoric and historic) were subject to agricultural developments, timber harvesting, and livestock grazing. Looting by artifact hunters also had an impact.

In 1968, the NPS developed an archaeological management plan for the park. The plan identified known cultural resources and sites at the park, what research had been completed at both sites, and what research was in progress. The plan identified the immediate research needs of the park in order to complete the park's basic operating goals.

Research needs included the identification of all historic structures; the identification of the American Camp cemetery; identification of Bellevue Farm and San Juan Town structures; and the evaluation of the Redoubt. The plan also stressed the need for a historic resource study of the sites.

Two major field schools have been held at the park through cooperative study arrangements with the University of Idaho (1970-78) and University of Washington (1983-90). The research completed by both schools has led to a wealth of artifact materials, both biological and historical, and fueled study on several different levels and topics, from shell middens to analyzing pottery sherds of the late nineteenth century.

University of Idaho

The University of Idaho, Moscow, was the first university the park worked with to complete archaeological studies at the park. From 1970 to 1978, under the leadership of Dr. Roderick Sprague, historical archaeological studies were completed analyzing site structures, including Bellevue Farm and San Juan Town. The goal of the field school's work was identification and stabilization of historic structures.

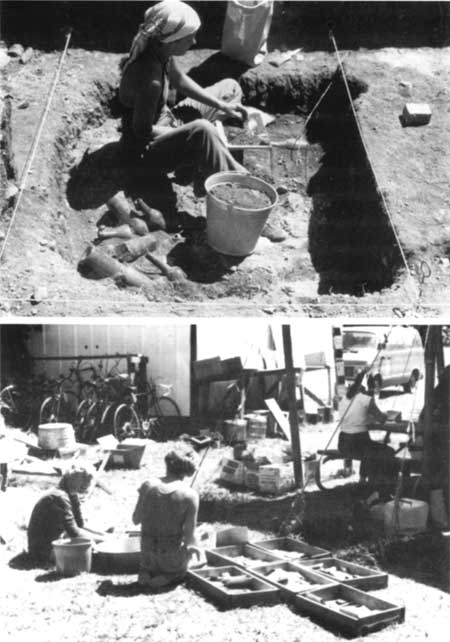

|

| The University of Idaho field school at work at English Camp, c. 1970. |

At American Camp, over a period of years the field school excavated the following structures: HS 1 Barracks, HS 8 Officers' Quarters, HS 10 Officers' Quarters, HS 11 Officers' Quarters, HS 12 Adjutant's Quarters, HS 13 Hospital, HS 19 Barn, HS 21 Carpenter Shop, HS 29 Woodsheds and Outhouses, HS 31 Post Trader and Billiard Room, and HS 33 Flagstaff. Of these structures, HS 6 and HS 8 were fully excavated. The remaining excavations produced a range of structural evidence from partial foundations or corner establishment to inconclusive structural evidence. The excavations also revealed the effects of rabbit damage. Rabbit burrowing was particularly destructive and compromised the structural evidence of the hospital. General surface collecting was done in areas of high visitor use and trenching was completed along officers' row and the camp fence lines.

At English Camp, the University of Idaho completed excavations first around HS 1 Blockhouse and HS 10 Barracks during reconstruction efforts in 1970-71. Trenching was done along the north, south, and east walls of the blockhouse, revealing evidence of a cobblestone "porch" in front, log cribbing, and one post hole. [14] The structure was completely excavated. The Barracks was also fully excavated and its foundation defined. HS 3 Commissary was also fully excavated, its foundation defined, in addition to the discovery of a Straits Salish long house underneath. Excavations around the hospital location produced some post holes but no conclusive evidence. [15]

In addition, the students completed test pits, trenching, and surface excavations trying to locate or define the following structures: HS 2 Barracks, HS 4 Blacksmith Shop (trenching produced remnants and residue of smithing operations but no conclusive structural evidence), HS 5 Captain's House, HS 6 Married Subaltern's Quarters, HS 11 & 12 Wash and Bath Houses, HS 13 & 14 Wells, HS 15, 16, 17, 31, 32, 33 & 34 unidentified structures (some structural evidence was revealed but primarily produced artifacts), HS 19 Stable, HS 20 Storehouse, HS 21 & 22 Messhouse and Library, HS 23 Carpenter's Shop and Sawmill, HS 24 Wharf, and HS 25 Pier (produce one stone piling). HS 35 Flagpole was located, in addition to the discovery of a complex structure, possibly another Salish structure, underneath. [16]

During the seven-year field school, the University also did test excavations around San Juan Town and Bellevue Farm. Eleven structures were examined at the town site and a great deal of artifact evidence removed for research. The town had some rabbit burrow damage, but most site damage was produced by artifact hunters during the mid-twentieth century. [17] Operations in the Bellevue Farm vicinity produced structural evidence of approximately eight structures, one of which dated post-1900, too recent for an HBC structure. Research of artifact accumulation at those sites to explain structure function succeeded in identifying the kitchen, but little else conclusively.

In 1983, the university produced a two-volume report titled San Juan Archaeology which covers the research completed from 1970-78 and subsequent analysis and research of the excavation findings. A majority of park data resulted in papers and dissertations on ceramics and late nineteenth century trade patterns.

University of Washington

While University of Idaho students completed studies of historic archaeology at the park, the University of Washington (UW) focused on the prehistoric archaeology in the park. In addition to the pre-NPS work done by UW scholars, Stephen Kenady supervised the work being done on the prehistoric sites exposed by the University of Idaho students during the 1970s.

In 1983, Julie Stein and Pamela Ford of the University of Washington, in coordination with PNRO Regional Archaeologist Jim Thomson, developed a research proposal for a field school at English Camp. Superintendent Hastings supported the proposal. Through a cooperative agreement, the university worked at the camp on the San Juan Island Archaeological Project from 1983 to 1989.

The field school focused its efforts on a large shell midden located in the center of the parade ground at English Camp. Students worked during the summers through 1989 examining the midden. The mostly biological artifact evidence extracted for research comprises the collection currently being stored at UW. Analysis of the shell midden data resulted in Deciphering a Shell Midden, edited by Julie Stein and published in 1992. The book details the project's findings regarding lithic technology and manufacture, stratigraphy, sediment analysis, effects of historic settlement, geophysical exploration work, and sedimentary analysis, among other topics. Project archaeologists utilized the site to produce research, documentary evidence patterns, and site treatments that can be used on shell middens elsewhere in the world.

|

| University of Washington field school student at work; the camp lab, 1984. |

Guss Island

Located in Garrison Bay and owned by the park, Guss Island is the site of several prehistoric human burials and a shallow shell midden. The island is considered culturally sensitive due to its use as a sacred burial site and access to the island has been closed to the public since the NPS took stewardship. Unfortunately, this does not prevent people from going to the island.

The low banks of the island have been subjected to a great deal of erosion, which has exposed burials. Visitors discovered and brought to the park headquarters remains exposed in 1970. [18] In 1983, after more burials were exposed, Julie Stein and Pamela Ford conducted a salvage excavation to pull exposed burials from the banks. These remains were given to the Lummi tribe for reinternment elsewhere in the park.

Eroding shorelines will continue to expose burials on the island. Current understanding with the Lummi is that exposed burials be allowed to erode. [19] However, as visitors and islanders become aware of the burials, excavation and reinternment may be considered as a preventative law enforcement measure.

Prehistoric Archaeological Overview and Base Map

In 1988, Dr. Gary Wessen of Wessen and Associates prepared A Technical Overview of Prehistoric Archaeology of the San Juan Islands Region for the Pacific Northwest Regional Office. Wessen provides an excellent review of known prehistoric archaeological sites in the region and reviews what documentation, collections inventory, and final reporting have been achieved for all excavated sites.

The overview begins by offering an environmental assessment of the islands, current conditions vs. paleo-environmental conditions. An ethnographic background of the region is also provided. In both of these background assessments, Wessen describes the islands as a whole and then looks specifically at American and English Camps. Wessen then provides an assessment of prehistoric cultural resources that exist in San Juan County and in the park, including a breakdown of typical site typology.

Wessen concludes that there are 323 recorded prehistoric sites in the islands and possibly hundreds more in existence. [20] Wessen's research concluded that for most of those sites excavated, little is known about them because of incomplete research, reporting, and cataloging/inventory of site evidence. The overview discusses what short, middle, and long term goals should be pursued in order to understand, preserve, and learn from the wealth of sites on the islands and at the parks, and stresses that the sites are deteriorating faster than they are being studied.

Additional Studies

The NPS has completed general survey and Section 106 compliance for all general park construction efforts: trailer pad sites, the headquarters building site, construction of the by-pass road and reestablishment of the old county road portion, among others. As previously stated, survey work of the hillside at English Camp was completed by Bryn Thomas of Eastern Washington State University as part of the Historic Landscape Study field work. This study revealed larger cultural remnants from the historic period along the hillside than were previously known, and which await further study.

|

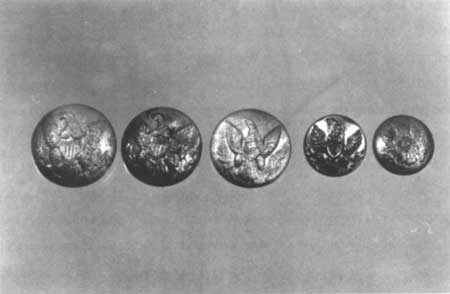

| Royal Marine medallion, recovered during University of Idaho field school. |

|

| U.S. Army uniform buttons discovered at American Camp. |

Collections Management

The purpose of San Juan Island N.H.P. collections, according to the 1981 scope of collections statement, is to "preserve the archaeological, historical and natural history objects necessary to research, document and interpret the significance of the park." [21] The collection is broken into three management areas: archaeological, historical, and natural history. Archaeological collections consist of materials generated from excavations, and will be maintained through agreements with the University of Idaho, including storage, cataloging, and inventory. Historical collections will be kept on-site, providing they deal with the HBC; the military encampments; settlers specific to the campsites; and a small selection of Crook materials. The scope stated that no natural history objects were currently being maintained, but the document speculated that it could become a viable collection option in the future.

The statement goes on to detail proper procedure in accessioning, cataloging, loaning, de-accessioning, and storing artifacts and items. The living history demonstration materials are identified as needing secured storage separate from the main collection. An addendum to the collections management plan regarding the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act was completed in 1992, well after the park had already returned and reinterred remains affiliated with the Lummi tribe.

Following preparation of the scope of collections, the park negotiated an agreement with the University of Washington to catalogue and maintain artifacts extracted during UW field schools, at the University's Burke Museum in Seattle. Currently, the park's collection contains approximately 935,400 archaeological items, 500,000 of which are prehistoric in nature and reside at UW. The remainder of the collection previously stored at the University of Idaho, contains approximately 400,000 items from the historic period, 1853-1874. During 1992, it no longer became an option to store the collection at the University of Idaho and a cooperative curatorial agreement was reached with North Cascades National Park in return for budgetary assistance from the park. The collection is now stored at the Marblemount collections facility. In addition, approximately 53,000 HBC-related items were sent to Fort Vancouver National Historic Site (FOVA). [22] HBC collections were sent to FOVA as part of a regional mission to make FOVA the center for HBC-related collections and research. In-park collections are stored in a leased storage space in Friday Harbor.

|

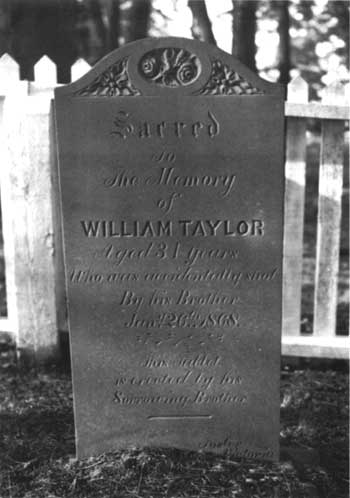

| The headstone of William Taylor, from the English Camp Cemetery. |

Recently, the option of a natural history specimen collection has been reviewed by park staff and will be developed in the near future to facilitate the development of a natural resource data base. Park management realizes the need for an updated scope of collections statement to address new collections, and to define the best management of current collections for the next decade.

Natural Resources

Water

Most people are surprised to learn the annual rainfall levels for the San Juan Islands. Lying in the rain shadow of the Olympic Mountains, the islands receive an average annual total of 29 inches. Water shortage is nothing new to the island and it is an issue all development on the island must address. Water shortages occur during the summer months, when visitation is highest. Shortages in 1985 resulted in the UW archaeological field school and the park splitting the cost of buying water for project excavation needs.

English Camp falls within the normal island average for rainfall. However, at American Camp, the southernmost point in the islands, the annual average is only 19 inches. Maintaining a proper water supply at American Camp has been a difficult issue for the park service. It has also been a public relations issue, as development on Cattle Point has pressed the NPS for access to water sources in the American Camp area.

In 1987, the Cape San Juan Water District requested to drill water wells on park property. They proposed the wells would aid in the park's fire management needs. In return for drilling the wells, residential development on Cattle Point would be allowed access to them. Superintendent Hoffman, in consultation with the regional office, declined their request. The water district representatives inquired about going above Hoffman to have their request re-appraised. Hoffman informed them that they had every right to do so, but let them know the regional office had already helped him make the decision and that a congressional delegate would hear the same answer from the park and region.

The park has consistently maintained its position regarding water access at American Camp for Cattle Point development, despite outside attempts to exert pressure through political channels and through public opinion. The NPS position remains that allowing developers access to American Camp water would not solve their problem. Inadequate water supply was one reason that large scale development had not occurred prior to preservation under national park service management. Residential use on Cattle Point combined with increased visitor use would dry up the park. The park's resources simply are not adequate to support anything beyond visitor use and facility needs.

In 1994, Cattle Point Estates requested drilling, testing, and utilization of a number of potential well sites on Mt. Finlayson with a 100-foot protective easement. The park denied the request. In 1996, they repeated the request, this time also requesting access to two capped wells on park property. When the second request was denied, the park received a congressional inquiry from Senator Slade Gorton's office about the denial. The park sent the same response to Gorton's office outlining their reasons. The park received no further communications from the senator's office. [23]

Rabbits

The rabbit populations on the island have been a problem for all residents, not just the park. However, the park has the largest concentration of them at American Camp. Introduced in the 1880s by settlers, the European rabbit was established as a wild animal on the island by 1895. In the 1920s and 30s, the rabbit population soared. The prairie setting of American Camp was prime burrowing land for the animals.

The rabbit population presents a few problems for the park service. The rabbits construct "warrens", and their burrowing and grazing destroy the historic prairie setting that the park aims to preserve. One rabbit in a year can burrow 20 meters and researchers estimated in the mid-1980s that some of American Camp's warrens were over 30 years old. [24] The rabbit's grazing patterns also affects the park's efforts to replant and regenerate native plant species.

Burrowing in general creates a safety hazard, and notices asking visitors to mind their step to avoid broken ankles are posted. On another level, burrowing can cause damage to subsurface cultural resources and structures and may have threatened the Redoubt's structural stability. The rabbits can also entice armed hunters, and hunting is illegal in the park.

Park management has speculated about methods of controlling the creatures and what should and should not be attempted to control them. In the end, nature has come through with its own regulation methods, much to the mystery of those who have studied the rabbit populations throughout the years. In 1980, 1981, and 1983, rabbit birth rates fell off. Females were miscarrying and the birth rate dropped dramatically (commonly referred to as "the crash"). Rabbit levels remained low during the mid-1980s.

Research has been completed by University of Washington professors W. Fredrick Stevens and A.R. Weisbrod, who also completed an interpretive book for sale to the public, titled The Rabbits of San Juan Island National Historical Park. The university conducted studies of the rabbit from 1973 to 1984, through the decline. Then in 1985, Olympic National Park biologist Doug Houston began a ten-year study of the rabbits. Houston annually counted warrens and took a photographic record of vegetation changes through eleven camera points. By 1995, the eleventh year of Houston's studies, the rabbit population was again on the rise, with abandoned warrens being repopulated.

Currently, the park has no plans for the rabbits and continues to monitor population levels. While not back to pre-crash levels, the rabbit population has risen considerably again.

Birds

Eighteen species of raptors have been observed on San Juan Island, including Peregrine falcons and marbled murrelets. [25] Bird species commonly seen in the park include wild turkeys and Canada geese. Bald eagles, the only known threatened species to inhabit the park, often draw visitors interested in wildlife viewing. During the 1970s, the park was involved with the Seattle zoo in environmental programs focusing on Bald eagles. During the 1990s, a pair of bald eagles nested right outside the visitor center at American Camp. Monitoring of bald eagle nests and populations continues to be a source of data collection for park staff. The rabbit population and prime hunting grounds on the open prairie will continue to support raptor population within the park.

Clams

In 1973, Vincent Gallucci, a biologist with the University of Washington, initiated extensive studies of the twelve species of clams in Garrison Bay. His studies, completed through the University of Washington Friday Harbor Marine Lab, received the support of the Washington State Department of Fisheries. For over twenty years, Gallucci studied the population dynamics of Garrison Bay's intertidal clams.

Gallucci's research also led to the development of an interpretive brochure for park visitors. The brochure offers guidance on clamming, when to watch for red tides, and biological information of the twelve species types.

Research Permits

In 1984, the NPS revised the Code of Federal Regulations to institute a formal permit system for research in parks. For San Juan, this program was very beneficial, since study opportunities abound and monitoring the progress of studies that had been approved often resulted in little information for the park. The system requires filing a request form, which will then be either approved or denied. The permit is issued for a one-year period, at which time the researcher submits a summary of studies completed. To continue research, permits must be renewed annually. By requiring annual reporting, the park's library and resource management data base benefits.

Resource Management Plans

Resource management planning for the park has been problematic. The nature of RMPs requires regular updating and, up until 1996, approval by the regional office. Due to staffing levels and the lack of a resource management specialist position, both updating and getting approval usually did not occur prior to the next scheduled revision. In 1987, Chief Ranger Steve Gobat writes with enthusiasm that for the first time the park had a RMP approved by the regional office prior to it becoming outdated. [26] You can hear the frustration when Frank Hastings writes, reflecting on the process ten years later, that the RMP "was updated again and again", without progressing forward and accomplishing anything that the plan called for. [27]

The first RMP for the park was completed in 1979. The document breaks management needs into the following categories: landscapes, historic structures, non-historic structures, natural scene, and archaeology. For each of these areas, the plan gives the current status and the conditions sought. The plan then lists problems preventing the development of ideal conditions.

The major problems identified in the planning document were issues that had been addressed before in the park's master plan and general management plan. The landscape at American Camp was extremely altered and would need further study to determine how to control rabbit populations and not deplete bald and golden eagle levels. Visitors had no sense of the campsite at American Camp, and this needed to be remedied. In addition, the Redoubt needed to be stabilized and restored. All non-historic elements should be removed from the scene, including utility lines and non-historical structures. To remedy these needs, the plan suggested research, both historical and archaeological, on the structures; recreation of period fences, both around the military camp and Bellevue Farm; and restoration of Officers' and Laundress' Quarters. Natural resource data base studies and monitoring programs were recommended for rabbits, eagles, and other wildlife.

The RMP was reviewed and a new version drafted in 1982. The difference between the two documents is tremendous. The 1979 plan is fairly unreadable, confusing, and not clear in its direction. The 1982 plan offered very specific park proposals and programming for each project. The plan would stay basically in the same format until 1995.

In 1982, the park's natural resource needs were identified as follows:

1. wildfire protection management

2. rabbit management

3. exotic thistle control

4. development of a forest management plan

5. natural resource basic inventory

6. native plant basic inventory

7. stabilize or remove big leaf maple at English Camp

Cultural resource needs identified:

1. restore formal garden at English Camp

2. locate and catalog all artifacts

3. develop an on-site collections facility

4. create a structure rehabilitation program

5. remove a portion of old county road at English Camp

6. research/stabilize masonry ruins

Under the reorganized park service structure, approval authority now comes from the park superintendent. The role of the regional office has been shifted to technical support only. The previous trouble the park had with RMPs being delayed while at the regional office for review and approval should not occur, providing the park with improved capability for project planning and implementation.

Interdisciplinary Planning Team

During 1982 the regional office teamed with park staff and regional scholars who had completed previous scientific studies at the park to develop new resource management objectives. The team, headed by James Agee, identified several areas in resource management planning where the park was deficient and identified six team objectives for improving the park's resource management progam:

Objective 1: define more precisely resource management objectives for the park.

Objective 2: develop a conceptual ecological model for park resources.

Objective 3: conduct a study into factors causing the rabbit decline.

Objective 4: describe and map historic landscape of American Camp and detail new problems/impacts of the rabbit decline.

Objective 5: Rewrite the resource management plan.

Objective 6: Document team process used for the study.

The team was very pointed in saying that the park lacked not only a resource data base but also the expertise to deal with the issues at hand.

The new RMP was available in 1986 and was approved in 1987. The new RMP has basically the same resource management needs and same problems identified in the previous plan. Natural resource planning needs identified included: recreation of the historic setting; creation of a resource database; establish water quality monitoring at Garrison Bay; establish rabbit management; forestry management; fire management; exotic plant control; a management plan for Young Hill trail; and control of vehicle and off-road vehicle access at American Camp. To address these needs, the plan programmed specific park projects: rabbit management, exotic plant control, restoration of historic scene, develop fire access roads, monitor pollution on Garrison Bay, design a Developed Area Tree Management plan (hazard tree), re-evaluate trails at Young Hill, and establish boundary markings.

For cultural resources, needs identified were: lack of protection for prehistoric sources; need for collections management control with an on-site facility; meet NPS-28 by completing an administrative history; and maintain the British Camp name. To address these needs, the plan programmed projects in the following priority: administrative history; archaeological investigations; cemetery protection/management; utilize foundations or ghosting of structures; develop a collections facility; reestablish historic fencing around military sites; create a historic structures preservation guide; rehabilitate historic structures; stabilize the masonry ruin; and maintain the British Camp name. Immediately the next year, the projects were reprioritized, probably due to changes in funding opportunities.

The most important change for the park's resource management program came in 1992 with the addition of a full time resource management position. It cannot be emphasized enough that the duties generated by resource management needs are too numerous to be handled by the Chief Ranger alone. Since the creation of this position, the resource management plan was completely rewritten (1995) and the number of resource management projects identified jumped from less than 20 to over 80.

In 1993, Dr. James Agee of the University of Washington School of Forestry completed a Vegetation Management Plan that provides guidance to restore the natural elements of the park's cultural landscapes. This is a long-term plan and has received the approval of the state's Historic Preservation Office. The plan has provided additional direction for the park's fledgling resource management program, whose development will continue to be a priority for park management. Resource management is an evolving program that requires the small park staff to wear many hats, be it law enforcement, interpretation, or resource management.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

sajh/adhi/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 19-Jan-2003