|

SITKA

Administrative History |

|

Chapter 1:

DESCRIPTION OF THE RESOURCE

| INTRODUCTION |

|

|

Indian River, before 1882. (H.H. Brodeck photo, Sheldon Jackson Collection, #2115, Presbyterian Historical Society) |

Overview

This section describes the area now known as Sitka National Historical Park. It discusses its geographic location, environment, component resources such as Indian River, the Indian fort site, the battleground, the Russian sailors' memorial, the totem poles, the cultural center, the Russian Bishop's House, the Russian blockhouse, recreational usage, and their values, and the significance assigned to those values. It examines the intent of executive and congressional actions taken in the 1890s and early 1900s to reserve the area.

Geographic location

Sitka National Historical Park lies adjacent to, and because of "outholdings" such as the Russian Bishop's House and the Russian blockhouse, actually in, the Southeastern Alaska fishing and lumber processing port of Sitka.

Sitka, with its population of approximately 8,000, is the largest community on the west coast of 1,607-square-mile Baranof Island. It is also the fourth largest community in Alaska. It is 95 air miles southwest of Juneau, 185 air miles northwest of Ketchikan, 590 air miles southeast of Anchorage, and almost 900 air miles north of Seattle. [1]

Physical Environment

Although it lies on the eastern edge of the North Pacific Ocean, Sitka is sheltered from the violence of those waters by Sitka Sound. Around Sitka is the rainforest-like vegetation typical of Southeastern Alaska. This dense growth of Sitka spruce, western hemlock, and Alaska cedar rises to timberline on the steep slopes of the Baranof Mountains. Various berry bushes, devil's club, and other undergrowth form a dense cover for the forest floor. Alpine tundra is found above treeline, typically around 2,000 feet.

Moisture-laden clouds moving in from the ocean dump about 97 inches of precipitation, including 50 inches of snow, on Sitka each year. This heavy, but sporadic, rain and snowfall is complemented by strong south or southeasterly winds with average annual speeds of eight to ten knots. Temperatures range from the 40s to the 60s in summer and from the teens to the low 40s in winter.

Natural wildlife found in the Sitka area includes bear, deer, mink, and otter. Other wildlife that has been introduced by human intervention includes mountain goats, martens, and squirrels. Sea mammals, such as sea otter, were once plentiful in the Sitka vicinity but were hunted to near extinction in the nineteenth century. Other sea mammals such as harbor seals, sea lions, porpoises, and several species of whales have survived in the waters near Sitka. Ocean fish indigenous to the Sitka area include sockeye, chum, pink, and coho salmon and numerous types of bottom fish. Fresh water fish in the area include steelhead, rainbow, cutthroat trout, and Dolly Varden. Other sea life nearby includes Dungeness, tanner, and king crab; clams, scallops, abalone, sea urchins, octopus, and sea cucumbers. [2]

Cultural Environment

The Sitka area is historically the location of a large Tlingit Indian year-round village. That complex and rich culture was supplemented and impacted by Western culture in the late eighteenth century when Russian fur traders arrived both to trade and later to occupy the area. The Battle of Sitka, commemorated by the park, in fact resulted in the Kiksadi Tlingits leaving the Sitka area for some twenty years. The Kiksadi eventually returned to Sitka at the invitation of the Russians. The Russians themselves were later supplanted by Americans who arrived in October of 1867 to occupy the Russian posts there and in other areas of Alaska.

Thus Sitka's cultural environment is a mixture of Tlingit, Russian, and American cultures. That mixture is reflected in the variety of resources that have been identified over the years in what is now Sitka National Historical Park.

| COMPONENT RESOURCES |

Early component resources

President Benjamin A. Harrison set aside much of the area now known as Sitka National Historical Park by proclamation in 1890. The area, of approximately 50 acres, was described as:

The tract of land bounded on the west by the line established by the survey made for the Presbyterian Mission, and along the shore line of the bay at low tide to the mouth of Indian River, and across the mouth of said river and along its right bank for an average width of 500 feet, along said bank to the point known as Indian River falls, and also on the left bank of said river from said fall an average of two hundred feet, from said falls to the eastern line or boundary as shown on the mission plat, for a public park.

The President designated the area as a public park, but did not further specify the values to be protected. His proclamation also, in its first paragraph, set aside nearby Navy Creek as a water source for naval and mercantile vessels and reserved the whole of Japonski Island for naval and military purposes. [3]

District of Alaska Governor Lyman E. Knapp initiated the chain of events that led to the proclamation. In November of 1889, Knapp advised Secretary of the Interior John W. Noble that it was time to reserve lands that might be needed for coaling stations, government wharves, public buildings, parade grounds, and bar racks at Douglas Island, Juneau, Kodiak, Sitka, Unalaska, and Wrangell. He cited the possibility that Congress would extend the land laws of the United States to Alaska during its next session. Knapp reported that some individuals in Alaska had begun to stake pre-emptive claims in anticipation of Congressional action. [4]

Early in the 1880s, three of the naval officers stationed at Sitka had claimed homesteads extending from what later became the location of Sheldon Jackson College to Jamestown Bay. In 1882, the officers refused to relinquish their claims in favor of the school but they never perfected them. Also in 1882, American Civil War veteran Nicholas Haley filed a homestead claim "on Indian River N. bank, all above high tide. It shall be known as the Sitka Park and Haley's Homestead." Haley, too, never perfected his title, but the claims clearly indicated that the traditional park on Indian River was in danger of going into private ownership. [5]

The secretary responded to Knapp with the suggestion that he empanel commissioners who would make recommendations regarding lands in Alaska that should be set aside for public purposes. Knapp then appointed commissioners in several communities. For Sitka, he selected John G. Brady, missionary and merchant; Lt. Cmdr. O.W. Farenholt, commanding officer of USS Pinta, the navy vessel stationed at Sitka from 1884 to 1897; and Henry H. Haydon, Surveyor General and ex-officio Secretary of Alaska. Knapp asked the three to

serve jointly as commissioners to examine and report as to what lands in and about Sitka should be permanently reserved by the Government for its uses for public buildings, barracks, parade grounds, parks, wharves, coaling stations, or other purposes. [6]

The commissioners made their recommendations in a March 31, 1890, report to Governor Knapp. Without explanation, they stated:

We would also recommend for reservation as a public park all that plat of ground, bounded on the West by the line as established by the survey made for the Presbyterian Mission, as above referred to, and along the shors [sic] line of the Bay at low tide to the mouth of the Indian River, and across the mouth of said River, along its right bank for an average width of 500 feet along said bank, to the point known as Indian River Falls: and also on the left bank of said river from said falls, an average width of 200 feet from said falls to the Eastern line or boundry [sic] as shown on the Mission plat. [7]

The commissioners' recommendations were summarized for Secretary Noble in an April 2, 1890, letter from the governor. The secretary, in turn, forwarded the recommendations to the President on June 9, 1890. The President responded with his proclamation, quoted in part above, and an endorsement appended to the secretary's letter.

June 21st, 1890

In accordance with the recommendation of the Secretary of the Interior, the above-described tracts of land in the Territory of Alaska are hereby reserved for the uses and purposes described by the Secretary, until otherwise directed by Congress.

(signed)

Benj Harrison [8]

Park-like use

Park-like usage of the area on Indian River had begun prior to American purchase of Alaska in 1867. That usage had continued after the purchase and there were local efforts, publicly sponsored, to maintain its facilities and expand its attractions.

In the early 1860s, Russians used the trail through the woods to Indian River for regular recreational walks. According to one source, it was not used recreationally before that because the Russians feared attacks by the Indians. [9] Another visitor to Sitka, this one just after the American purchase of Alaska in 1867, reported recreational use of the Indian River area by Russian families living in Sitka.

The Russians, who for months past had been greatly enjoying the few fine days we did have, made all the use they could of this warm spell and on practically every bright summer afternoon they went with their wives and children out into the open country . . . sometimes to the Indian River which flows into the bay at its north-east end about a mile away from the settlement -- as already stated, this walk to the river was the only one along the sea-front.

These land excursions were often very animated and cheerful. A shady spot was chosen on the bank of the limpid, rushing mountain stream and everyone set to work to collect dry wood. Under the care of one skilled in such matters a bright fire was soon burning and the inevitable copper samovar boiling over it. [10]

In the American period, reports and photographs that preceded the proclamation cited the "lovers' lane" that ran through the park, its vegetation, scenic vistas, and the river itself as worthy attractions. [11] Indian River was an early recreation destination point for Sitkans out walking for pleasure. The river itself, clear but shallow, and nearby vegetation were attractions. [12]

Tourists, then known as excursionists, also began to visit Sitka in the 1880s. The first steamship load arrived in 1882 aboard South Dakota. Vacationing in the Far North became fashionable. The numbers of touring visitors increased as the years passed: 1,650 in 1884; 2,753 in 1886, 3,889 in 1887, 5,432 in 1889, and 5,007 in 1890. [13] Most visitors seem to have included Indian River in their visits to Sitka. The path through the woods known as Lovers' Lane provided easy access to the river's banks. According to a traveler's guide written in the early 1880s, the lovers' lane was an extension and improvement of a Russian-constructed walk along the beach and through the woods. [14]

|

|

Lovers Lane, 1908. (Photo courtesy of Anchorage Museum of History and Art, #B63.19.3) |

In 1884, 2d Lt. Howard H. Gilman, USMC, officer-in-charge of the U.S. Marine Guard at Sitka, used a party of Marines and Indians to clear a new pathway from the beach to the river. His crews constructed additional paths on either side of the stream and bridged it twice. He had two other bridges built over ravines on the river bank. Leaving the river banks, the Marine-built paths also explored the woods themselves.

Both the 1884 traveler and an 1886 successor noted the skill with which Gilman had laid out the paths to display natural features. They especially mentioned the crystal clear waters of Indian River, gigantic trees, ferns, huge green leaves of the "devil's club," mosses, grasses, and lichens. The off-shore vista, "Every foot of island . . . sketchable, and a picture in itself;" also received recognition.

Another observer, a naval officer stationed in Pinta in 1888, later recorded that "The Indian River . . . is beautiful and celebrated in history and romance." [15] Such comments were reinforced by most writers who visited Sitka in the late 1800s. [16]

Improvement of the recreational values continued in the 1890s. In 1895 a new trail was cut from "the Point to the Bridge" along Indian River. Three years later the local newspaper noted that "Everyone who comes to Sitka goes there [Indian River]." The paper urged that the park be cleaned up and that new benches and walkways be provided. [17]

A revised, 1899, travel guide by the 1884 author elaborated with the information that in 1844 Indian River had been so thick with salmon that a canoe could not be forced through. [18] By the end of the century, trout predominated and salmon could be caught only occasionally. [19]

Indian River protection

Indian River protection was increased in 1910. President William Howard Taft used the authority of the Antiquities Act of 1906 to declare the area on Indian River to be Sitka National Monument. The monument came into being as a result of efforts by William Alexander Langille, supervisor of Tongass National Forest. The forest had come into being on July 1, 1908, when the Alexander Archipelago Forest Reserve that dated from 1902 and Tongass National Forest that dated from 1907 were joined. The combined forest area encompassed most of Southeast Alaska. Langille had first come to Alaska in 1897 as a part of the Klondike gold rush. Guiding experience in the Oregon mountains had brought him into contact with leaders in the national forestry movement.

Gifford Pinchot, head of forestry for President Theodore Roosevelt, called Langille from Alaska to Washington in 1902 and thereafter appointed him as a forestry expert. In 1905, Langille became supervisor of the Alexander Archipelago Forest Reserve and subsequently head of the larger Tongass National Forest. He had, according to a historian of the U.S. Forest Service activity in Alaska, "as many duties as Pooh-Bah of Gilbert and Sullivan's Mikado." [20]20

|

|

Indian River bridge, probably in 1904. (Photo courtesy of Anchorage Museum of History and Art, #B63.19.3) |

In 1908, Sitka Post No. 6 of the Arctic Brotherhood desired better protection for the area known as Indian River Park. It was natural that they should turn to Langille for advice. Langille recommended that the brotherhood petition the President of the United States to declare the area a national monument. He offered to prepare a sketch map of the area and to see that the petition and map went to the President. [21] After review by District of Alaska Governor Walter A. Clark and United States Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot, Secretary of Agriculture James S. Wilson submitted the petition with map and photographs to the Secretary of the Interior. On March 23, 1910, a presidential proclamation created Sitka National Monument. [22]

Component resources in 1910

When Sitka National Monument was created in 1910, officials identified several significant resources in the area now known as Sitka National Historical Park. These included

the decisive battle ground of the Russian conquest of Alaska in 1804, and also the site of the former village of the Kik-Siti tribe [sic], the most war like of the Alaskan Indians; and . . . also . . . the graves of a Russian midshipman and six sailors, killed in the conflict, and numerous totem poles constructed by the Indians, which record the genealogical history of their several clans. [23]

"The decisive battle ground of the Russian conquest of Alaska in 1804" referred to the beach area over which Russians assaulted a fortified camp of the Kiksadi Tlingits in late September and early October of 1804. [24] The events leading up to the assault, its conduct, and its consequences are discussed in subsequent chapters.

The battle site, or its immediate vicinity, may also have been the scene of a second confrontation. According to one account, in 1855 Indians destroyed a small Russian settlement in the area. [25] This is borne out to some extent by an 1852 map that shows three buildings in the area now occupied by the western half of Sitka National Historical Park, just south of where the trail from Sitka ended at Indian River. The map also shows two other buildings and cultivated ground on the east side of the river. [26]

It is probable that rather than a "settlement" the buildings marked simply provided shelter at an outlying garden or fishing site. The "site of the former village of the Kik-Siti tribe [sic]" was the location to which they had moved in 1804 from their main village adjacent to and including the downtown Sitka feature first known as Nu-Tlan and later as Castle Hill. The move anticipated what became known as the Battle of Sitka. Reportedly, the Indian River location was a summer fishing camp of the Kiksadi Tlingit that had been fortified in anticipation of a battle with the Russians. The 1880 census gave some indication, by reporting a population of 43 Tlingits at "Indian River," that Kiksadi use of the area as a summer fish camp may have been resumed sometime in the nineteenth century. [27]

The rhomboid-shaped walled fort, approximately 240 by 165 feet in its longest dimensions, enclosed 14 structures. After the Indians abandoned the fort, the Russians burned it. [28]

The Russian sailors' memorial location was known through Sitka tradition long before establishment of the national monument. The Arctic Brotherhood's petition to the President noted that the memorial was the location of the grave of personnel from a Russian man-of-war who had been "killed and buried where they fell" in the September 1804 battle. According to the brotherhood, Alexander Baranov, in 1804 Chief Manager of the Russian American Company's activities in Alaska, had caused a wooden monument to be erected over their grave "which public-spirited citizens have since kept more or less in repair." [29]

The memorial site appears on Langille's 1908 sketch map as a small fenced area. An attached photograph shows a rectangular picket fence enclosing a Roman cross. Langille's report "on a proposed national monument at Sitka, Alaska," describes the memorial as "the burial place of a Russian midshipman and six sailors killed by the Indians on the day following the decisive engagement of 1804...." [30]

Research in primary sources to date has not accounted for the location of the memorial or the type and number of persons reported to be buried there. None of the sources consulted mentions disposition of the bodies of casualties from the Battle of Indian River. Details regarding the number and nature of casualties vary.

Urey Lisiansky commanded the Russian warship that took part in the battle. He states that two sailors were killed and a number of sailors and officers wounded. A Russian American Company official reports the casualties as including two naval lieutenants and three sailors. The fur trading company's official history identifies one wounded naval officer, Povalishin, as a midshipman and gives the number of sailors killed as three. [31]

The Arctic Brotherhood's 1908 petition does mention that the "Graeco-Russian Church" was heading a movement to erect a permanent monument at the memorial site. [32] It is not known if any thing resulted from this. In 1916, J.A. Moore, Special Agent for the General Land Office, was recommending that the memorial be marked. Ten years later, the Reverend A.P. Kashevaroff, curator of the Territorial Library and Museum, was making the same recommendation. [33] This too may have come to naught, but the memorial apparently was long a point of commemorative significance to Sitkans and eventually became another point of interest for visitors to Sitka.

The totem poles were from throughout Southeast Alaska. In 1901, the U.S. Revenue Cutter Rush relocated a tall totem pole, four house posts, and a war canoe given by Chief Saanaheit of Kasaan to the park. In 1903, Alaska Governor John G. Brady collected 20 additional poles from Prince of Wales Island, about 125 miles south of Sitka. The sources included the Tlingit villages of Tuxekan and Klawock, and the Haida villages of Howkan, Klinkwan, Sukkwan, Old Kasaan, and Koinglas. Brady gathered the poles with the promise that they would go to the United States government. [34]

|

|

Totem poles at Old Kasaan, 1908. (Photo courtesy of Alaska Historical Library, Case and Draper Collection) |

Brady shipped the poles, house posts, and canoe to St. Louis for the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition. After the exposition, some of the poles were sold. Others went to Portland, Oregon, for display at the Lewis and Clark Exposition. After their display at Portland, Brady is said to have had 14 of the 20 poles shown at the exposition placed in the public park at Sitka. [35] E.W. Merrill was engaged to arrange the poles "artistically." Lanille's 1908 map of the monument, however, shows only 13 poles. [36]

|

|

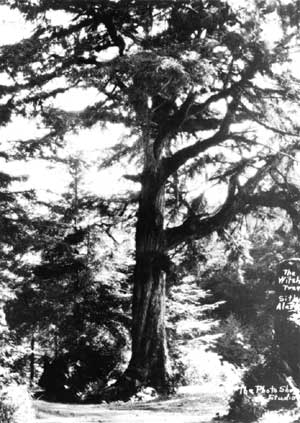

The "Witch Tree," one of the early points of

interest in Sitka National Monument. (Photo courtesy of Sitka National Historical Park) |

Witch tree and recreation use

Without making distinctions regarding significance, documents leading to the Presidential Executive Order cited above also mentioned the Sitka reserve's resources as including a "witch tree" and noted that it had been "for generations . . . a place of recreation for Sitka people." [37]

Sitka tradition identified the witch tree as one to which a witch had been tied for a cleansing process. In a procedure very similar to New England witch hunts, those identified by Tlingits as witches were given a chance to admit their guilt before being put to death. To some who saw it, the tree's appearance suggested sorcery. For many years photographs of the tree could be purchased at the Photo Shop in Sitka. Barrett Willoughby, a travel and romance writer who had spent some of her childhood in Sitka, reported in an account of an early 1900s return to Sitka that the tree was also one under which the Indians held their important tribal councils. She also said that the Indians recorded significant events by "driving plugs into its soft gray bark." The huge hemlock "plushed with amber moss and tufted with little green ferns" was washed away when the river flooded during World War II. [38]

Supplements to original resources

The original list of component resources was supplemented as the years passed. Various officials suggested adding resources that were either not immediately, or were never, made a part of the monument.

In 1916, for instance, General Land Office Special Agent J.A. Moore recommended without result that Sheldon Jackson Museum, nearby on the campus of the Sitka Training School, be acquired for the monument. [39]

Visual aesthetics within the monument were identified again as monument values in the early 1920s. Alaska Road Commission and National Park Service officials opposed wheeled vehicle traffic inside the monument in order to preserve the attractiveness of the area. [40] The vista from the monument toward the sea also came under consideration again. This occurred at least as early as 1923, when road commission and park service officials corresponded regarding the visual intrusion of a powerline that ran along the monument boundary. [41]

Wildlife resident in the monument had achieved recognition as values by 1924, when the President of the Alaska Road Commission notified National Park Service headquarters in Washington by telegram that a hunter had been apprehended shooting at tame deer and other wildlife in the park. [42]

In 1926, Stephen T. Mather, director of the National Park Service, approved efforts of the Alaska Historical Society and the Sitka Commercial Club to construct a replica of a Russian block house in the park. This activity added another value to the monument. [43]

The following year, in 1927, territorial and park service officials considered retrieving additional totem poles from abandoned Native villages in Southeast Alaska and relocating them in Sitka National Monument. This idea had been raised as early as 1921 and would be considered again and again without action through the 1970s. [44]

In 1933, Park Service officials rejected a feature that Sitka residents desired be added to the monument, a plaque commemorating Alaskan photographer E.W. Merrill. [45] In 1938, Chief of Forestry J. D. Coffman visited the monument. He reinforced the idea of the park as a place of recreation for Sitkans, with a description of its city park-like usage. [46]

Two years later, in 1940, the first park service employee stationed at the monument proposed acquisition of two properties being disposed of by the Coast and Geodetic Survey. In doing so, he noted their historical value. One site, where the Coast and Geodetic Survey had quartered its employees, was the location of the "Old Russian Tea Gardens." A no-longer-needed magnetic station and variation stand was cited as the site of an old blockhouse. [47] It is likely, however, that the proposed acquisition had more to do with the critical shortage of housing in Sitka than with the historical value of the property involved. Park service officials were in an acquisitive mood. That same year, Mount McKinley Superintendent Frank T. Been recommended that the service acquire Castle Hill and salvage the wreck of the Russian vessel Neva. [48]

Also in 1940, navy efforts to extract gravel from the mouth of Indian River stimulated consideration of the scenic values of the monument areas adjacent to Indian River. [49] This concern was expressed again the following year when National Park Service officials protested navy tree-cutting within the monument. [50]

World War II activity also added a series of machine gun pits to the monument. Remnants of these can be seen along the seaward side of Lovers' Lane. This fulfills, in part, the suggestion of an army officer with an unusual understanding of future concerns. A Maj. Pomeroy (First Name Unknown), in charge of sea coast defenses in the monument, took National Park Service personnel to the site of a gun and ammunition position. He suggested that it be left intact as after the war it would have historical value. [51]

Private property adjacent to the western park boundary was added to the monument on February 25, 1952. This increased the total monument size to 54.33 acres. [52]

One component park value was lost, and another created, in 1959 and 1960. In 1959, the replica Russian blockhouse constructed within the park boundaries in 1926 was bulldozed and burned because it had become a hazard to visitors. Then the park service began construction of still another replica blockhouse, this time in downtown Sitka. This replica, located on federal land managed by the Bureau of Land Management, was completed in 1961. [53]

A major new component resource was added to monument values in 1965 when the visitor center was dedicated. It incorporated a cultural center for traditional Native arts and crafts and a history museum.

The Department of the Interior's Indian Arts and Crafts Board had established a major retraining program for Alaska Native artisans at Sitka in 1962. When the new Sitka National Monument visitor center opened, the retraining program was moved there. The program included five related workshops: wood and ivory carving, metalwork, lapidary, stone carving, and design and block printing. Talented Natives were employed as demonstration aides to develop new and upgraded craft products.

It took some time to define the nature of the resource that the new cultural center represented. The National Park Service and the Indian Arts and Crafts Board funded it jointly. The Indian Arts and Crafts Board initially viewed it as a place where traditional arts and crafts from Native cultures throughout Alaska might be preserved and taught. Sitka's Tlingit community viewed it as a place most appropriate for preservation and teaching of Tlingit, or at most Northwest Coast Indian, arts and crafts that might be preserved and taught. The National Park Service viewed it as a place where Native arts and crafts could be demonstrated and interpreted, not as a training program.

The National Park Service was in the middle until the regional director recommended the Tlingit position to the national director. It was not until July of 1968 that the Indian Arts and Crafts Board grudgingly accepted the resource definition put forward by Sitka's Tlingits. [54]

The new visitor center also included a small history museum. Artifacts for the display came from Sheldon Jackson Museum and from a small collection that had been loaned or given to the monument itself by Sitka residents. [55]

The Russian Bishop's House was the last major resource added to Sitka National Historical Park. The National Park Service purchased it in 1972. This came a decade after the Secretary of the Interior designated the building, then known as the Russian Mission Orphanage, as a National Historic Landmark.

Landmark status for the Russian Bishop's House was based on the building's association with Ioann Veniaminov, then Bishop of Kamchatka, the Kuriles, and the Aleutian Islands (later Saint Innocent, Apostle to Alaska), most famous of the Russian Orthodox clergy to work in Alaska. Additional justifications for the building's landmark status included its role as the educational and administrative headquarters of the Orthodox Church in Alaska, and its importance as an example of period Russian architecture. [56]

The Russian American Company built the structure in 1842-1843 to serve as the residence, administrative center, and private chapel of Veniaminov. A school building, constructed in 1897; and a small cottage known as House No. 105, built in 1887, are satellites to the building. [57] In the early 1980s, traditional recreation values of walking for pleasure, natural history observation, and so forth were supplemented by a fitness trail constructed on the east side of Indian River.

| SUMMARY |

In summary, the component resources of Sitka National Historical Park include cultural, natural, and recreational resources.

The recreational resources were identified through customary usage by the mid-nineteenth century. They included such usages as walking for pleasure, picnicking and game-playing on the banks of Indian River, observation of the river, fishing in the river, enjoyment of the plants and animals that inhabit the area adjacent to the river, and appreciation of vistas to the seaward from vantage points along the walk to the river. These usages were formalized in the 1880s by civic action to enhance the park's recreational facilities through such activities as publicly-supported trail construction and in 1890 by the earliest reservation of the area as a public park. Recognition of the park's recreational values has since been continuous.

The cultural resources were first recognized in the early 1800s when Alexander Baranov had a monument erected to the sailors who were killed in the 1804 Battle of Sitka. Although recreational values predominated for many years, cultural resources began to become more important in 1901 when the first totem poles were placed in the park. The inventory of cultural resources was expanded and their recognition formalized in 1908 when the area was proposed as a national monument. At that time, cultural resources recognized included the 1804 battleground, the site of the former village of the Kiksadi Tlingits, the memorial to Russians killed in the 1804 battle, and totem poles and house posts relocated to the Sitka park. References to a "witch tree" are found in documents leading up to the designation, but not in the 1910 proclamation actually making the designation.

Visual aesthetics, including the beauty of the river, the environment inside the park, and vistas from the park, were recognized as park resources at Sitka at least by the early 1880s. Various species of wildlife were also recognized as park resources about this same time.

In 1926, a replica blockhouse within the park boundaries was added as a park resource. It remained one until 1959 when it was demolished. Its role was subsequently filled by a replica block house erected in downtown Sitka. Although the National Park Service maintains the replica, it does not own the property on which it sits.

In the mid-1960s, the visitor center and the cultural center it houses became park resources. In 1972, the last major resource to be added to date, the Russian Bishop's House and its satellite structures, became a part of the park. A decade later, the park's recreational resources were supplemented by construction of a fitness trail.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

sitk/adhi/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 04-Nov-2000