|

SITKA

Administrative History |

|

Chapter 2:

SITKA — HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

| OVERVIEW |

|

|

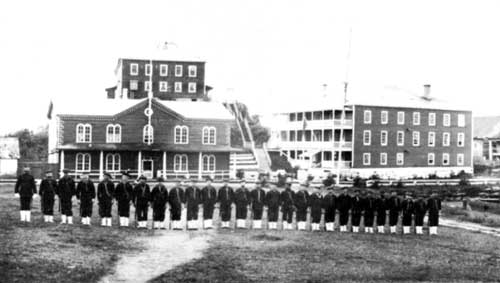

Far left, 2d Lt. Howard H. Gilman, U.S. Marine

Corps, with his Marine detachment from USS Adams on parade ground

at Sitka. Gilman led the effort to construct recreational trails at

Indian River before he left Sitka in August 1884. (Sheldon Jackson Collection, #500, Presbyterian Historical Society) |

This section briefly outlines the history of the community of Sitka. It provides a context for understanding the evolution of what is now Sitka National Historical Park. It includes a description of traditional Tlingit use of the area around Sitka before the Russians established a fort in the area. The battles of 1802 at Old Sitka and of 1804 at Indian River are detailed. Understanding the different national approaches to fulfilling government responsibilities in Alaska is necessary to understand changes at Sitka from the Russian period to the American period. Understanding the nature and remoteness of Sitka and Alaska is also necessary to understanding the development of the park.

| TLINGITS |

The Tlingits, the most northerly of the Northwest Coast Indians, occupied southeast Alaska possibly 10,000 years ago. Most archeologists believe that the Tlingits moved from the interior of today's Alaska and British Columbia to southeast Alaska. They followed the Nass, Stikine, and Taku rivers to their mouths, then fanned out to occupy the many islands. Although archeologists do not know for certain that Tlingits occupied it, a site on Baranof Island named Hidden Falls has been found. People lived there 8,000 years ago. When Tlingits first came to Sitka Sound is not known, but the Kiksadi Tlingits oral history indicates that they had a permanent village there for a number of years before Euro- Americans arrived. [58]

Because the Coast Mountains come right to the water's edge on Baranof Island, the large Tlingit winter village at Sitka stood on the beach. Fish, shellfish, and land animals were abundant in the area. This largess, combined with the moderate maritime climate, allowed the people to hunt and gather food relatively easily year-round. In late March the people began sea fishing for halibut and cod, and freshwater fishing for Dolly Varden. In early April, they gathered herring. Later that month, sea mammals migrating north passed through southeast Alaska waters. The Sitka Tlingits hunted sea otters, hair seal, fur seal, sea lion, and porpoise. Although whales passed en route north, the Sitka people did not hunt them.

Early in summer, most of the Sitka Tlingits moved to camps near the mouths of freshwater streams to fish for salmon. Kiksadi Tlingit families from the permanent village, Shee-Atika or "by the sea," at Nu-Tlan or Castle Hill, used a summer fishing camp, Gaja-Heen or "water coming from way up" at the mouth of Starrigavan Creek and another at the mouth of Indian River. The people most commonly trapped salmon in rock weirs or hooked them. Other Sitka Tlingits embarked on trading and war voyages early in summer. They might travel as far south as Prince of Wales and the Queen Charlotte islands. The Tlingits were frequently at war among themselves and with the Haida people to the south. They fought to obtain slaves, new hunting and fishing territories, and to increase their material possessions.

In late summer, families moved to hunting camps. There the women and children gathered berries, roots, and grasses. The men hunted deer, black bears, brown bears, mountain goats, and sheep. With the approach of winter, the Sitka people returned to the large village at Castle Hill. Year-round they could dig clams and gather crabs from the nearby tidal flats. [59]

The Sitka spruce forests that covered the lower elevations of Baranof Island provided wood that was used to build houses and provide heat. At their permanent village the Sitka people lived in large, rectangular, gable-roofed plank houses. The houses measured up to 30 by 40 feet. As many as 12 families and their slaves lived in a house. The Sitka village had a number of these houses. At their seasonal camps, the people had smaller wood structures. [60]

The people also used wood to make canoes. Although the coastal waterways through southeast Alaska were dangerous, they provided the best transportation routes through the region. The Tlingits had travel, war, work, and hunting canoes. A canoe was made from a single tree. Typically, the canoes were long, narrow, and high-pointed at the bow and stern. For their larger war canoes the Sitka Tlingits traded with the Haida people to the south who lived on Prince of Wales and the Queen Charlotte islands where western red cedar was available. [61]

| SOCIAL STRUCTURE |

Because of the mild climate and lush flora and fauna that made subsistence relatively easy, the Tlingits had time to develop a complex social system and to pursue a high degree of aesthetic creativity. The people based their beliefs on kinship and communication with all living things.

Tlingit territory encompassed most of today's southeast Alaska. It was divided into 13 or 14 areas called kwans that each had from one to six permanent villages. Three groups, the Sitka kwan, Husnuwu kwan, and Kake kwan, claimed parts of Baranof Is land. The west side of the island was the territory of the Sitkans. [62]

Within a kwan, there were clans based on kinship. Clans owned salmon streams, hunting grounds, berry patches, sealing rocks, house sites, family crests or emblems, and spirits. The head of the clan guarded its properties and directed trading activities. Clan chiefs had power, rank, and wealth. They belonged to the nobility. The nobility spoke for a clan and preserved its honor. The other people were commoners and slaves. Most Tlingits were commoners who did the necessary day-to-day work. Slaves could be captured or purchased. They performed the more onerous and dangerous tasks. Slaves were not members of the clans they served. [63]

Every Tlingit was a member of one of two social divisions in a village. One group was Raven. The other group was Eagle or Wolf. Children had to marry a member of the opposite group. Tlingits traced their descent matrilineally. Family members lived together in a clan house. They shared canoes, slaves, crests, songs, hunting, and ceremonial objects. The house leader, usually the oldest brother of the family matriarch, led ceremonial activities. [64]

|

|

Tlingit ceremonial festival, Sitka, date

unknown. (Photo courtesy of Anchorage Museum of History and Art, #B80.50.31) |

For events such as marriages, births, deaths, or the dedication of new crests or houses, the Tlingit people had elaborate rituals. When possible, members of a house hosted a potlatch for one of these events. Neighboring villagers were invited to come and feast and dance. The people told stories. The ceremonies involved giving and receiving gifts. Hosting a potlatch indicated wealth and social status. [65]

The southeast Alaska Native people carved elaborate designs on their ceremonial masks, rattles, dance paddles, and even everyday utensils. Although some carved posts were inside houses and some mortuary columns stood near the gravehouses on the ridge behind their village, totem poles were not part of the Sitka Tlingits' heritage until historic times. The Haida and Tlingit Indians to the south are better known for carving totem poles. Such poles served several functions. Crest poles gave the ancestry of a particular family, history poles recorded the story of a clan, legend poles related experiences real and imagined, and memorial poles commemorated an individual. All bore symbols or crests that belonged to a particular lineage, house, or family. Symbols used by the Tlingit Raven group included ravens, hawks, puffins, sea gulls, land otter, mouse, moose, sea lion, whale, salmon, and frog. Those of the Tlingit Wolf and Eagle groups included wolf, eagle, brown bear, killer whale, dog fish, ground shark, and halibut. Traditionally, the totem carver was a member of the clan opposite the person who commissioned it. [66]

| EURO-AMERICANS DISCOVER SITKA |

On July 15, 1741, Alexei Chirikov, commander of St. Paul, one of the ships of the second Bering expedition, recorded sighting what has been assumed to be Lisianski Inlet on the northwest coast of Chichagof Island. He reported a broad harbor at 57 degrees 15 minutes north latitude. Ten armed men in a longboat were sent ashore to explore the land. Days passed and the men failed to return. A second boat set out, but it too disappeared. Smoke from fires onshore could be seen, but three weeks passed and nothing was seen of the missing men. Some Natives in two small canoes paddled out from the bay where the boats had gone. When Chirikov tried to entice the people in the canoes to come aboard St. Paul, both canoes turned away. On July 27, Chirikov and his officers decided to return to Kamchatka. St. Paul had no small boats left and without them it was impossible to send parties ashore to obtain critically-needed fresh water. [67]

After the existence of land in the North Pacific was documented, navigators from several different European countries set sail to explore the Northwest Coast. Possibly the next to see Baranof Island was Don Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra, a Spanish navigator. In August 1775 he sailed his 36-foot schooner Sonora into today's Krestof Bay, which he called Port Guadalupe. Quadra wrote of a mountain "of the most regular and beautiful form I have ever seen." He named the mountain San Jacinto. [68]

Three years later the famous British explorer, Capt. James Cook, named the peak Mount Edgecumbe, the name that is used today. The Russians called the mountain Saint Lazaria, assuming the peak was the one seen by Chirikov and so named by him. Cook's crew brought to the world's attention sea otter pelts taken from animals found in the waters of the North Pacific. Be cause of its extraordinarily glossy sheen and its fluffiness, the sea otter pelt was highly valued by the Chinese. The sea otter brought the Tlingits on Baranof Island into contact with Euro-Americans. [69]

| THE FIRST RUSSIANS AT SITKA |

By 1799 Sitka Sound was a favored trading spot for Euro American traders. The Russians considered the predominantly British and American traders to be intruders in their domain. After a visit to the Sitka Sound area in 1795, Alexander Baranov, Chief Manager of the Shelikhov-Golikov Company, one of the companies organized into the Russian American Company in 1799, determined to build a trading post at the site. On July 7, 1799, Baranov returned to Sitka Sound with several other Russians and a number of Aleut hunters. Baranov negotiated with the local Tlingit chief for the right to occupy a tract of land at the mouth of Starrigavan Creek, four miles north of the large permanent Sheeatika village at Castle Hill. Construction of Archangel Saint Michael's Redoubt began immediately. The Russians built a large warehouse, stockade, blockhouse, blacksmith shop, residence for Baranov, quarters for the hunters, and a men's house. During the winter the Tlingits unsuccessfully attacked the post several times. Business called Baranov to Kodiak in 1800. [70 Baranov left written instructions for Vasilii G. Medvednikov, whom he left in charge, discussing treatment of area Natives and construction of the fort. In the instructions, Baranov also pointed out the need to strengthen the company's economic and political position in southeast Alaska. It is clear from the instructions that the Russians feared the local Tlingits. After Baranov's departure, 25 Russians and 55 Aleuts staffed the post. In spring 1802, the population of the post was 29 Russians, 3 British deserters, 200 Aleuts, and some Kodiak women. [71]

Materialistic and militant, the Tlingits were shrewd traders and fierce enemies. The Russian traders had protested foreign competition for furs to their government and had appealed to the British, Spanish, French, and United States traders not to trade guns and ammunition for furs. By the late 1790s the fur trade competition in the North Pacific was keen, and few traders cooperated with the request of the Russians.

The Sitka-area Tlingits were divided among themselves in their feelings toward the Russian settlers. In June, 1802, a group of hostile Tlingits from Indian River and nearby Crab Apple Island led by a chief named Katlean attacked the redoubt. They looted and burned the barracks, storehouses, and fur warehouses. They more than 4,000 sea otter pelts and burned a ship being built. Most of the Russian and Aleut workers were killed. The dead numbered 20 Russians and up to 130 Aleuts. A few Russians and Aleuts who had been away from the post hunting or who fled into the forest later reached British and American trading ships that arrived in the harbor and relayed the news. Capt. James Barber of the British ship Unicorn held a Tlingit chief and several other Indians captive until the Russian and 18 Aleuts captured during the attack were turned over to him. Barber delivered the survivors and the news of the attack to Baranov at Kodiak on June 24. [72]

In late September, 1804, Baranov returned to Sitka Sound with a large Russian and Aleut force to re-establish the redoubt. The 1,150 men were supported by four ships with cannon. One of the ships, Neva, had recently arrived in Russian America. Its commander, Urey Lisiansky, later wrote an account of the battle that ensued. The Sitkans permanent winter village was clustered around Castle Hill. When the Russian ships sailed into sight, the Tlingits abandoned the village in favor of a stronger fortification to the east by Indian River, Shish-Kee-Nu, or "Sapling Fort." The Kiksadi Tlingits fortified the site in anticipation of the Russians' return. Fourteen buildings enclosed by a thick log wall stood at the site. The Tlingits reportedly numbered 750. The site provided fresh water and a potential route of escape. Further, the gravel shoals extending from the river's mouth prevented close approach by large vessels. [73]

On September 29, the Russians went ashore at the winter village. Lisiansky named the site New Archangel. That evening a Tlingit ambassador came from the Indian River fort. The Russians asked that the chiefs come to visit. The ambassadors returned several times. Baranov asked that the Russians be permitted to occupy Castle Hill. When negotiations broke down, the Russians advised the Tlingits that they planned to begin firing at the Indian River fort. The Russians returned to their ships, moved them close to the fort, and began firing on October 1.

The Russians bombarded the Tlingit camp with 16 guns for several days. Then a number of Russians went ashore and battle ensued at Indian River. Baranov led the Russians. Chief Katlean led the Kiksadi Tlingits. A few men were killed and some wounded, including Baranov. The Russians were forced to return to their ships. They renewed their bombardment. Because their supply of gunpowder was exhausted and because they were afraid of the treatment they would receive from the Russians if captured, the Tlingits chose to abandon the fort and flee across the mountains to the north. After the Tlingits fled, the Russians burned the fort. [74]

The Russians were not sure where the Tlingits had gone. For a long time, all Russian hunting parties were on constant guard against attack. A few days after the battle, eight Aleuts were killed in Jamestown Bay and another was shot in the woods near the Russians' new fort. [75]

The Tlingits escaped by following Indian River to its head and crossing the mountains to Katlean Bay. There they constructed canoes and moved to "Olga Point" where they lived for a year before moving to "Deadman's Reach" and finally to Sitkoh Bay on Peril Straits. At Sitkoh Bay they built a new village called Choch-Kanu, Halibut Fort. [76]

The Russians built a new settlement, called Novo Archangelsk or New Archangel although generally known as Sitka, at the site of the Tlingit village at Castle Hill. The Russians named the hill Castle Hill, because it was the site for the Russian American Company governor's home. Although Baranov had his house on the hill, the first structure known as Baranov's Castle was built on the site in 1837, long after the first governor's death.

Around the kekur or hill, the Russians built a high, wooden stockade with three blockhouses, all armed with cannon and muskets. Almost a thousand trees were cut for the stockade. Inside the stockade, warehouses, barracks, and workshops stood. By summer 1805, 8 buildings had been finished and 15 gardens had been planted. As late as 1858, Tlingit warriors sporadically attacked the town and groups who were away from the post. [77]

| SITKA BECOMES RUSSIAN AMERICA CAPITAL |

In August 1808 New Archangel became the capital city of Russian America and the administrative center for the Russian American Company that had been chartered by the Russian government in 1799 to be its sole fur trader in North America. At that time, the Russians claimed land in North America that stretched along the coast from Norton Sound to California. Sitka became the cultural and commercial center for the Russians in North America. Officers and employees of the Russian American Company brought their families to Sitka. In 1833, 406 Russians lived at Sitka. With them were 307 Creoles (of Russian fathers and Native Alaskan mothers) and 134 Aleuts. [78]

Ships from many European countries and America that came to the North Pacific to trade for furs, hunt whales, or explore stopped at Sitka. A shipyard had been established shortly after the town was founded. Over the next fifty years many vessels were repaired at the shipyard. Others were built there, including several steam vessels including Nikolai I and Muir. The steam engine for the latter was built at Sitka as well. [79]

The community had brickyards, tanneries, and a foundry for casting brass, copper, and iron. At two sawmills near Sitka, Russians cut lumber for ships and buildings. Workers caught and salted fish for food and sale at several sites near the community. In the 1840s and 1850s, the Russians cut and shipped ice from the lakes at Sitka to California. For the ice industry they created Swan Lake, known to them as Labaishia Lake, from a low swamp. [80] An 1809 map of Sitka identifies a well in the center of town. An account in the 1840s identifies a cistern, thought to be at the same site, for water that was hauled about half a mile from a spring on a mountain-side. [81]

As part of the company charter, the Russian government required the Russian American Company to provide support for Russian Orthodox clergy in Russian America. In 1816, the Russians constructed the original Saint Michael's Russian Orthodox Church close to the ocean. In 1848 they replaced the church with a cathedral that was built in the center of town. In 1842-1843 the Russian-American Company built the Russian Bishop's House for the church. It is believed that Finnish ship builders constructed the two-story log building, which measured 63 feet long and 42 feet wide. Two frame additions, called galleries, were at the east and west ends of the building for stairways, latrines, and storage. They were to form an air space between the outdoors and indoors. Each gallery was 42 by 14 feet. The building became the center for the administration of the Russian Orthodox Church in Alaska. [82]

The Kiksadi Tlingits returned to Sitka in 1821 and settled out side of the stockade. The area where they lived was commonly referred to as the ranche. The Tlingits and Russians never lived completely in harmony. The Russians allowed the Tlingits inside the stockade only during specified hours each day and locked the gates at sundown. If a Native was selling fish or game to the company, the transaction was conducted at a small window at the gate by one of the blockhouses. [83]

By 1825, the community also had a hospital, an observatory, a library, and a museum. For outdoor recreation Sitka residents went boating, hunting, or on walks and picnics to the deep woods near Indian River. A route known as the Governor's Walk went from the wharf, through town, to Indian River. Cards, masquerades, theatricals, and dinners were common indoor recreation activities. The officers of the company had a club that Governor Adolf Etholin established in 1840. In general, the Russian settlement differed from most others in the New World in the 1700s and the 1800s because it was established by employees of a company who came to do a job instead of seeking religious freedom or to seek homes for themselves. [84]

| AMERICANS TAKE OVER |

By the 1860s Russia's interest in North America was waning. It had relinquished its claims to lands south of Prince of Wales Is land in the 1840s. The sea otter were virtually extinct in Alaska waters. Efforts to engage in whaling or in the land fur trade had not been economically successful. Company profits had declined. The settlements in Russian America had not become self-sufficient. Their remote location would make them difficult to defend. Russian and United States representatives signed a treaty to sell Russian America to the United States for $7.2 million on March 29, 1867. The U.S. Congress ratified the treaty on June 20, 1867 The formal transfer ceremony took place on Castle Hill at Sitka on October 18, 1867. Alexei Pestchouroff, commissioner of the tsar, formally transferred all of Russian American to Maj. Gen. Lovell H. Rousseau, commissioner for the United States.

After the formal transfer of ownership, many details had to be attended to. Russian citizens in Alaska were given the option to return to Russia or become American citizens. At least 537 people left Alaska for Russia on Russian American Company vessels in 1867-1868. The Native people were expected to obey American laws, but did not become citizens until 1924. The U.S. Government made no provision for a territorial government. The first efforts to organize a civil government at Sitka in 1869 failed for lack of interest and lack of laws and the government disbanded in 1873. [85]

Instead, the American government assigned the U.S. Army to administer affairs in Alaska. An Alaska District was created, with headquarters at Sitka. Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis was the first commanding officer. The five sub-posts established around the territory at Tongass, Wrangell, Kodiak, Kenai, and the Pribilof Islands in 1868 were closed in 1870 and the district was merged with the Department of Oregon headquartered at Vancouver Barracks, Washington.

A number of fortune seekers, traders, and adventurers, most from the western United States, rushed to Sitka in 1867 and 1868. The warehouses of the Russian American Company were emptied; much of the stockpiled merchandise was carried to San Francisco. With no organized government, drunkenness, crime, and prostitution flourished. The soldiers stationed at Sitka were no better behaved than the civilians. After the initial activity, Sitka's economy declined. [86]

By 1870 when the U.S. Army conducted a census of the residents at Sitka, the population totalled 391 Russians and Creoles, 49 Americans excluding military personnel, and an estimated 1,200 Natives. [87]

The town had several stores, meat shops, a barber shop, a bakery, a sawmill, two breweries, and many saloons. Sitka traders collected about $20,000 worth of pelts that year. The other major economic activities were fishing and shipping. The Tlingits continued to be allowed into the center of Sitka only during the day. One of the army's activities at Sitka in 1869 was construction of a one and one-half mile corduroy road from the town to Indian River to enable wagons to haul water and wood. [88]

The U.S. Army troops left Sitka in 1877. The remaining representatives of the U.S. Government were the customs collector and deputy and the postmaster. The non-Native people at Sitka felt that the military presence had guaranteed safety from attacks by the Indians. A week after the troops departed, Sitka Tlingits tore down a portion of the stockade. Tensions between Natives and non-Natives at Sitka increased, until the non-Natives appealed first to the United States and then to the British for protection. The British sent HMS Osprey from Esquimault, Vancouver Island, to Sitka. Osprey arrived before USS Alaska. They found all quiet at Sitka. Following the public outcry over this incident, the U.S. Government assigned the navy to administer affairs in Alaska. The navy stationed Marines and a gunboat at Sitka. Although the U.S. Government established a civil government five years later, the navy remained at Sitka until 1912. [89]

In 1884 Congress passed an Organic Act that provided for an appointed governor of Alaska and four commissioners. President Chester A. Arthur appointed John H. Kinkead, Sitka's postmaster, to be Alaska's first governor. The district headquarters for these government officials was Sitka.

| SITKA SETTLES DOWN |

For a few years after the purchase of Alaska, Sitka continued to be the center for the collection of furs in Alaska. In contrast to the Russian system, more than one fur trading company operated in Alaska under the Americans. Sitka was not close to the richest fur trading areas and increasingly was bypassed by the fur traders and trading companies. Trade in furs, however, continued to be a major local economic activity at Sitka. During their heyday in the 1910s and 1920s, a few fur farms operated in Sitka and on several of the islands nearby. [90]

Among those who came to Sitka following the purchase were a number of prospectors. In 1870 gold was found at nearby Silver Bay near the town. For many years miners worked a mine in the upper Indian River valley. Ten years after the first discovery, Joe Juneau and Richard Harris were grubstaked by Sitka resident and miner George Pilz. They discovered placer gold in creeks near today's Juneau. Following that discovery, many residents of Sitka left for the booming mining towns of Juneau and Douglas. Gold mining continued in the Sitka area, however, until World War II. More than three-quarters of a million ounces of gold was recovered from Sitka area mines. Gypsum, discovered in 1902, was commercially mined in the Sitka mining district until 1923. [91]

To reach some of the mining sites, a bridge was built over the lower portion of Indian River in 1888. Funds to build the bridge were raised by subscription. I.B. Hammond built the bridge at a cost of $142.50. The last mention of the structure was a call for additional funds so that the structure could be painted. [92]

American missionaries also headed for Sitka during the 1870s. The Reverend John G. Brady and Fannie E. Kellogg, of the Board of Home Missions of the Presbyterian Church, opened a school for Native children in 1878. Later, the school became Sitka Industrial Training School, and subsequently it was named to honor the long-time Presbyterian missionary Sheldon Jackson. [93] The Russian Orthodox Church continued its mission at Sitka after the 1867 transfer. In 1897 Monk Anatolii Kamenskii, working at Sitka, re quested funding from the church for a school building. The Russian Bishop's House, then used as an orphanage, was too crowded and in need of repair. [94]

In a few short years, Juneau surpassed Sitka in population and economic activity. When larger mining operations started at Juneau and nearby Douglas and those boom towns became more stable communities, people began to clamor to have the capital of the district moved from Sitka to Juneau. In 1901 the decision was made to move the capital. The actual move, however, was not completed until 1906.

The loss of the government payroll impacted Sitka and between 1900 and 1910 Sitka's population declined 25 percent. As the fishing and fish processing industries grew between 1910 and 1920, the population grew by 13 percent. In 1878 the Cutter Packing Company opened one of the first two salmon canneries in Alaska at Starrigavan Bay near Sitka. Although it closed shortly after the 1879 season, several other canneries opened in the vicinity during the 1880s. A few salteries operated for several years as well. A market developed for halibut, and a cold storage plant opened at Sitka in the early 1900s. For a brief time during the 1910s a shore-based whaling station operated at nearby Sitkalidak Island. A herring fishery flourished during the 1920s and 1930s. Over the years a number of fishermen and cannery workers made Sitka their home. [95]

Sitka's other major economic activity was tourism. In 1879, John Muir made the first of five trips to Alaska. Upon his return to California, he wrote several articles about southeast Alaska. Others ventured north. Some, such as Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, wrote accounts of their trips that were subsequently published. Beginning in the 1880s, increasing numbers of people began to visit Alaska to see its scenic wonders, Native people, and evidences of its Russian heritage. All of the steamships stopped at Sitka. [96] Many Russian buildings still stood in the town. The Russian Orthodox Cathedral with its beautiful icons was a major attraction. In the 1890s the town residents restored Baranov's Castle, but the wooden structure burned in 1894. In addition to viewing the buildings, visitors could purchase Native artifacts such as baskets and wood carvings, and follow the boardwalk from the wharf through town to the 1804 battle site and Indian River. [97]

The thousands of people who headed to the Klondike gold fields in 1897 and 1898 bypassed Sitka. The community was not along the Inside Passage route that took stampeders from San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle to Dyea and Skagway. The increased attention paid to Alaska as a result of the gold discoveries in the north impacted Sitka in other ways. An agricultural station opened in 1898, and the station's chief made Sitka his head quarters. A magnetic observatory opened the same year. After Tongass National Forest was created in 1902, the U.S. Forest Service had a ranger at Sitka. When the submarine cable was completed in 1906, Sitka was connected to the rest of the world by telegraph. [98] But for the most part, after the capital moved, Sitka was a small, relatively isolated community during the early 1900s. Fishing, fish processing, and tourism were the mainstays of the local economy. Several residents wrote that the major event in town was the weekly arrival of the mail boat. Beginning in the 1920s, a few float planes brought visitors and a little freight to town. The population was around 1,200 people.

In 1913 Sitka was selected by the first Territorial Legislature as the location for the first Pioneers' Home for indigent prospectors who had spent many years in Alaska. In 1934 a large, second building was added. Southeast Alaska Natives organized the Alaska Native Brotherhood at Sitka in 1912. The group formed to fight for citizenship rights and equal treatment. Camps soon organized in other Southeast Alaskan communities, and a companion group, the Alaska Native Sisterhood, also formed. By 1920 Sitka had become a small, stable community that changed little until World War II. About 1904 the Sitka Wharf and Power Company tapped Indian River for a water-distribution system that served the center of town. A water-wagon, filled at Indian River, served outlying areas. As late as 1940 the U.S. Marshal had the people in jail run the water wagon to Indian River. After the five- gallon cans were filled they were delivered to residents for $5.00 a week. Around 1942 and 1943 additional water lines were constructed to serve more parts of the town. [99]

Just before World War II started, the U.S. Government began a military build-up that included establishing bases in Alaska. The old naval reservation on Japonski Island was selected for a U.S. Navy seaplane base. From there, PBY airplanes could patrol the North Pacific. An army base opened at Sitka to guard the naval station. In addition, a radio "beam" station was constructed on Biorka Island, and gun emplacements were installed on Harbor Peak and on several islands in Sitka Sound. The military personnel and construction crews brought new life to Sitka.

|

|

Naval Air Station, Sitka on Japonski Island,

1944. (Photo courtesy of Alaska Historical Library) |

After the war ended, the bases closed. The government transferred their buildings to the U.S. Department of the Interiors' Alaska Native Service for use as a medical and education facility. The hospital was one of the main centers for treatment of tuberculosis during the late 1940s and early 1950s. It was transferred to the U.S. Public Health Service in 1955. In 1948, the Bureau of Indian Affairs opened a secondary-level boarding school, Mt. Edgecumbe High School, at the site. It served Native children from throughout Alaska. In 1985 the State of Alaska took over operation of the school. Sheldon Jackson Industrial Training School evolved into a college offering two and four year programs. After statehood in 1959, the State of Alaska opened a Public Safety Academy at Sitka, and a few years later the University of Alaska started a community college there. Sitka became a regional education center.

Several sawmills operated at Sitka throughout the 1900s. Lumber from Sitka had been important in building the gold rush boom towns of Dyea and Skagway. Some lumbering occurred over the years. After World War II, there was increased interest in leasing areas on Baranof Island for logging. A Japanese-owned pulp mill at the mouth of Silver Bay began operating in 1959. Sitka's population increased by 63 percent as approximately 500 people found work at the mill. In 1977, the Coast Guard established an air station on Japonski Island, in part to enforce the new 200-mile offshore fishing limit. [100]

The tourism industry flourished in the post-World War II era as more people learned about Alaska. Until the mid-1950s steamship companies offered passenger service and organized tours, particularly through southeast Alaska. As it had been before the war, Sitka was a favorite tourist stop. The national monument, availability of Native arts and crafts, and remaining structures from the Russian period, most particularly St. Michael's Cathedral, attracted people. In January 1966, the wooden cathedral burned. Fortunately, measured drawings of the structure had been prepared by the U.S. Forest Service and completed by the National Park Service in 1962. Sitka residents spearheaded an effort to reconstruct the cathedral on its original site, which by the 1960s was in the center of downtown Sitka. For the Alaska Purchase Centennial in 1967, the State of Alaska improved a commemorative park atop Castle Hill with can non, interpretive markers, and flagstaffs. That same year, the city opened its community Centennial Building and the Sitka Historical Society started a museum there. The Visitor Center at Sitka National Monument, built in 1965, further enhanced tourism. The federal Board of Indian Arts and Crafts had started a program at Sitka in 1962 and its Native artists moved to the new center. About the same time the Sitka Summer Music Festival began. During the 1960s transportation improvements brought more visitors to Sitka. The State of Alaska began its Marine Highway system in 1963. In 1967, jet air service to Sitka from Anchorage and Seattle started. In 1972 the national monument was redesignated a national historical park and its mission expanded to interpret the Russian experience in Alaska. The Russian Bishop's House was added to the park. There had been 150 buildings in Sitka in 1867. When the house was added to the park, it was one of only four buildings surviving from 1867.

The 1980 census gave the population of Sitka as 7,803. Ten percent of the people are Alaska Natives. [101]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

sitk/adhi/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 04-Nov-2000