|

Timpanogos Cave National Monument Utah |

|

NPS photo | |

High on the slopes of American Fork Canyon in the shadow of mighty Mt. Timpanogos in Utah's Wasatch Range are three moderate-sized limestone caves: Hansen Cave, Middle Cave, and Timpanogos Cave. These exquisite caverns display dazzling helictites and anthodites in a variety of fantastic shapes. In the tradition of the National Park Service, Timpanogos Cave National Monument preserves these caves and all their fragile underground wonders for you, and for others in the years ahead, to enjoy.

The World of Caves

For thousands and thousands of years, Hansen Cave, Middle Cave, and Timpanogos Cave were dark—silent perhaps, except for the sound of water dripping—and unknown. Then the first light of a candle, a lantern, a flashlight flickered in these underground realms, and their secrets were revealed.

Imagine the excitement and disbelief of the early explorers as light fell on the many colorful and delicate sculpted forms of the caves. There must have been a childlike delight in discovering and naming incredible features like the Chimes Chamber, the Camel Room, and the Great Heart of Timpanogos. How did this special world come to be? Speleologists—scientists devoted to studying the mysteries of caves—search for answers to such questions. At Timpanogos Cave National Monument the unusual colors, abundant helictites and anthodites, and the development of the caves are of particular interest. It is thought that the caves were formed along fault lines and later dissolved out by water. Research brings answers to these and other questions—and it brings new questions.

Discovery!

Over 100 years ago no one knew that there were caves hidden in American Fork Canyon. Then on a fall day in 1887, 40-year-old Martin Hansen, a Mormon settler from American Fork, Utah, accidently discovered the first cave. Hansen was cutting timber high on the canyon's south slopes when, according to one version of the story, he came across the tracks of a mountain lion. Following the tracks to a high ledge, he found an opening in the rock—the entrance to the small cave that would be named after him. Hansen did not enter the cave that day. but he returned later to explore.

Hansen and others hacked out a rough trail straight up the mountainside. By all accounts, the first visitors found the cave exceptionally decorated with colorful deposits of flowstone and other formations. Within only a few years, however, souvenir hunters and miners had damaged the cave, selling much of their treasures to museums and universities and to commercial enterprises who made decorative objects from the cave deposits.

Not until 1915 was a second cave discovered. That summer a group of families from Lehi, Utah, came to American Fork Canyon for a day's outing. While the rest of the group explored Hansen Cave, teenagers James W. Gough and Frank Johnson climbed around the rocky slope outside. By chance they stumbled across a hole not far from the entrance to Hansen Cave, it was the entrance to Timpanogos Cave. Many people explored the cave, seeing its exquisite formations, including the Great Heart of Timpanogos, but for some reason knowledge of the cave and its whereabouts faded.

Then on August 14, 1921, Timpanogos Cave was rediscovered. An outdoor club from Payson, Utah, had come to American Fork Canyon to see Hansen Cave and investigate rumors of a second cave. It was Vearl J. Manwill, a member of the club, who confirmed the rumors by rediscovering Timpanogos Cave. That very night, "by the light of campfire, [we) discussed our find." Manwill wrote, "and talked about ways and means to preserve its beauty for posterity instead of allowing it to be vandalized as Hansen's Cave had been." The people around that fire dedicated themselves to the cave's preservation.

The excitement of rediscovering the natural wonders of Timpanogos Cave had not yet died when a third cave—Middle Cave—was found that fall. George Heber Hansen and Wayne E. Hansen, son and grandson of Martin Hansen, were in American_Fork Canyon hunting deer. As they looked through binoculars at the south slope of the canyon from the opposite side, they spotted an opening near the other two cave entrances. Within days they returned to this new cave—Middle Cave—with a large exploring party equipped with ropes, flashlights, and candles. In the party was pioneer cave-finder Martin Hansen, by then 74 years old.

The hopes of all those who sought to protect and preserve the caves of American Fork Canyon were realized a year after Timpanogos and Middle Caves were discovered. In 1922, at the urgings of Utah citizens, the U.S. Forest Service, and others. President Warren G. Harding issued a proclamation establishing Timpanogos Cave National Monument, Since that time the caves have been officially recognized as natural features of national significance and extraordinary scenic and scientific value.

Underground Delights

Some of the Earth's most powerful and most delicate forces combined to create the wonders of Hansen, Middle, and Timpanogos caves, beginning when the Wasatch Range was building 30 million years ago. Tremendous mountain-building forces slowly uplifted and fractured the sedimentary rock.

The caves were dissolved later along fractures now called the Hansen, Middle, and Timpanogos faults in the Deseret limestone. Apparently rising hot water and descending cold water were important factors in the caves' origins. Natural weak carbonic acid dissolved the rock to form the caves, which were created at the level of an ancient water table and later invaded by a stream for a short time.

Then a change occurred. Water that filled or partially filled the caves drained. As more water seeped into the air-filled caves, it decorated them with fantastic formations. Water trickling through the limestone overlying the caves dissolved calcite and other minerals from the rock. Then, upon entering an underground chamber, the water deposited its mineral load as a tiny crystal on a cave ceiling, wall, or floor.

Over thousands of years, as countless crystals were deposited, a variety of cave formations took shape—stalactites, stalagmites, flowstone, helictites, and others. Each had its own shape and size, determined by how and where the water entered the cave, how long it flowed, and other factors.

Today, the caves are still changing: new formations are being created, and existing ones are growing where mineral-laden water continues to enter. In Timpanogos Cave a stalactite-stalagmite pair are growing closer year by year; today they are only 34 inch apart, and if growth continues at the current rate, they will probably join in about 200 years. As long as water—the master architect and interior decorator—continues to trickle into the caves, creation will continue.

Helictites:: Stars of the Underground Show

Helicite, a strange and exotic-sounding word, is the name of a formation found in these caves. The tremendous number of helictites is one ot the hallmarks of the Timpanogos Cave system. Such quantities ot helictites, coupled with anthodites, are uncommon. Helictites twist and turn unpredictably in all directions, defying gravity. Usually less than ¼ inch in diameter and a few inches long, they aio as delicate—and fragile—as hand-blown glass.

Smooth but spiraling helictites are made of calcite; needle-like crystals are made of aragonite, a mineral chemically identical to calcite but with a different crystalline structure.

Cave explorers and speleologists have debated the origin of helictites since they were first discovered. From the beginning it was apparently understood that they were created in a much different way from such formations as stalactites, stalagmites, and other more common formations.

Some early spectators believed that helictites were created by mineral deposits on spider webs or fungi. Some thought their odd contortions were the result of the forces of electrical energy, cave winds, or earth tremors.

Today many speleologists believe that two forces peculiar to water guide the creation of helictites. Like crooked straws, most helictites appear to have a tiny central canal running along their length. Water is apparently pushed and pulled through this canal by capillary action under hydrostatic pressure. Together these two forces override the usual dominant force of gravity: controlled by these forces, water slowly seeps through the canal to the tip of the helictite, where it then deposits a crystal.

Some scientists further believe that the crystals do not stack neatly, but arrange themselves haphazardly one on top of the other, adding to the apparently random nature of their growth. Future research may shed new light on these unusual cave creations.

Stalactites and Other Common Cave Formations

Many different types of cave formations are; created by water simply dripping or flowing into the caves. Perhaps the most well-known of these are stalactites and stalagmites, which can be seen throughout the caves. Stalactites, which hang like icicles from the ceiling, form as drop after drop of water slowly trickles down through the cave roof.

The smallest stalactites may be hollow, thin, and straight, and so are called soda straw stalactites. Others may be massive: The Great Heart of Timpanogos in Timpanogos Cave—5½ feet long, three feet wide, 4,000 pounds—is composed of three, or possibly more, tremendous stalactites that have grown together. Traces of iron, nickel, manganese, and organics color stalactites and other cave formations.

Stalagmites are formed when mineral-laden water strikes the floor. The tallest stalagmite is about six feet high in Timpanogos Cave; most are smaller. Occasionally stalactites and stalagmites merge, forming a floor to ceiling column. The caves' largest column, 13 feet high, is found in Hansen Cave.

Another common formation—draperies—is created when water trickles down an inclined ceiling. A spectacular example is the Frozen Sunbeam, a thin translucent sheet of orange-colored calcite in Timpanogos Cave. Draperies in these caves are seldom over one inch thick.

The Cascade of Energy and the Chocolate Fountain, both in Timpanogos Cave, are examples of flowstone formations. As the name implies, the smooth coatings or sculpted terraces of flowstone are created when water flows down a wall or across a floor. An impressive specimen decorates a wall in the Big Room of Middle Cave.

Popcorn formations occur where water seeps slowly through pores in the rock or in thin films down rock walls. These knobby lumps abound in Timpanogos Cave, where they are mixed with helictites.

Underground Pools and Cave Creatures

Thirty mirror-like pools and lakes in the Timpanogos Cave system reflect their other worldly environs. Hidden Lake can be seen in Timpanogos Cave. In some pools, small wall-like formations made of calcite form rimstone dams.

Animals inhabit the caves but are easily overlooked. Cave spiders, centipedes, and crickets live here. An occasional bat roosts in the caves, but no large bat colony like those found in Carlsbad Caverns or in other caves exists here. Occasionally a pack rat, mouse, or chipmunk visits. Without an underground stream or steady source of food, the caves are not well equipped to support many cave species.

Like other cave features, the pools and cave animals are protected. Their survival depends on the National Park Service and on you. Preserving many ot the most important natural and cultural sites of the United States, all our national parks deserve our respect and careful guardianship.

Planning a Cave Trip

The caves are open daily for tours mid-May through mid-October, weather and funding permitting. The caves are closed in difficult or dangerous hiking conditions.

Tickets for cave tours are sold at the visitor center. In summer all tours usually sell out by early afternoon. Buy tickets in advance or arrive early in the day to avoid long delays.

To buy advance tickets, call the park up to 30 days before your visit or buy them at the visitor center up to the day before the tour. Weekends and holidays are the busiest.

When you buy tickets you are told when your tour starts. You may begin walking up the 1½-mile trail to the caves 1½ hours before your tour begins, which gives you ample time. In early morning there is usually only a short wait before you may start for the caves. The wait quickly lengthens; by late morning it may be two to three hours.

You can enjoy your time here in many ways. Ask a ranger for suggestions or see park brochures and exhibits. Do not start up the trail before your designated time; that only makes for a longer stay at the Grotto, a small waiting area near the caves' entrance.

The National Park Service wants you to enjoy the caves but must limit the number of visitors to protect delicate, irreplaceable features. Each tour has a 20-person limit. During the busy summer months, those able to buy tickets often wait several hours before they can start hiking to the caves.

Touring the Caves

This fascinating underground world has lured visitors for decades. Today all cave tours are professionally guided. The ½-mile tour lasts about an hour on a surfaced, lighted, and fairly level route. Your tour begins at the natural entrance to Hansen Cave and continues through Hansen, Middle, and finally Timpanogos caves. Touring the cool and wet caves requires some bending and crouching through the narrow passages. Bring a flashlight if you wish.

The caves' small chambers and passageways are packed with extraordinary features. Ceilings, walls, and floors are covered with stalactites, stalagmites, draperies, flowstone, and the helictites for which these caves are renowned. The profusion of bizarre, brilliant white helictites in the Chimes Chamber of Timpanogos Cave is a highlight of any tour. So is the Great Heart of Timpanogos, a giant cave formation consisting of several stalactites joined by draperies. Cave pools reflect cave decorations. Cave animals are rare, but you may see cave crickets, bats, or other creatures of the dark.

While in the caves, look but don't touch. It is tempting to touch, but delicate cave formations break easily and skin oils discolor them. Nature might take thousands of years to repair the damage, or the loss could be forever. Parts of the cave system can be wet and slippery; watch your step. Use high-speed film or a flash for taking pictures. Tripods are not allowed. For information on our specialized cave tours like the Introduction to Caving Tour call the park.

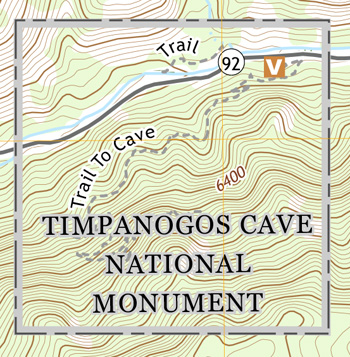

The Trail to the Caves

The trail up the steep northern slope of Mt. Timpanogos is physically demanding but rewarding. You climb 1,092 feet in 1½ miles on a zigzag, hard-surfaced trail from the bottom of American Fork Canyon to the cave entrance. Altogether the round trip to and through the caves and back down is 3½ miles; it takes about three hours.

Pace yourself: there is much to enjoy along the way. Benches allow you to rest, catch your breath, and enjoy outstanding views of American Fork Canyon, the Wasatch Range, and Utah Valley. Wildflowers grow beneath Douglas fir, white fir, maple, and oak. You may spot chipmunks, golden-mantled ground squirrels, lizards, and many species of birds. Just below the entrance to the caves are the only restrooms on the trail.

Bring along a jacket and drinking water. Drinking water is NOT provided on the cave trail or at the caves. The temperature in the caves is approximately 45°F (11°C), about like a refrigerator. Wear comfortable walking shoes. Consult your doctor before attempting this trail if you have difficulty walking or breathing, or have heart problems.

Because of the trail's steepness and the caves' narrow passages, wheelchair access is impossible. Baby strollers and other wheeled vehicles and pets are not permitted on the trail or in the caves.

Warning! Rocks fall often in American Fork Canyon. Red stripes mark the areas of greatest hazard on the trail; avoid stopping in these places. Be alert for the sound of falling rocks. If rock fall comes toward you, move out of the way or take cover, move close to rock walls, and protect your head. Don't throw rocks yourself. Stay on the trail; short-cutting causes erosion and can start a landslide. Running—especially downhill—is dangerous. Children under 16 must remain with adults responsible for their conduct and safety.

More Things to See and Do

Visitor Center

Stop here first to find out about caves, the human and natural history of

American Fork Canyon, and what to see and do in the park. Exhibits, brochures,

books, and a short introductory film are available. Park staff can answer

questions and help plan your day. The center and restrooms are accessible to

persons with disabilities. The center is open mid-May through mid-October; call

for winter hours. A snack bar and gift shop are open during the cave tour

season.

Picnic Areas

The park has a picnic area across from the visitor center and a larger one.

Swinging Bridge Picnic Area, ¼ mile west. Both areas are located on the

shady riverbank. Each has tables and drinking water. Swinging Bridge also has

fire grills and restrooms.

Canyon Nature Trail

This gradually descending trail winds along the floor of American Fork Canyon,

with views up and down the canyon and across to the opposite side, where the

caves are located. A trail guide is available at the trailhead or the visitor

center.

Accommodations and Services

Within 10 miles of the park nearby communities have gasoline, restaurants,

lodging, and groceries. There are public campgrounds nearby in the national

forest and state parks, and private campgrounds in American Fork, Lehi, and

elsewhere.

Nearby Places To Visit

Within a short drive of Timpanogos Cave National Monument are many places to

take a scenic drive, hike, horseback ride, fish, boat, or just enjoy the

day.

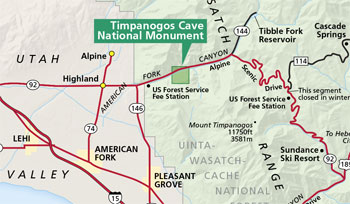

The 20-mile Alpine Scenic Drive winds through rugged canyons of the Wasatch Range offering stupendous views of Mt. Timpanogos and other glacier-carved peaks. The route follows Utah 92 up American Fork Canyon and continues through the national forest into Provo Canyon on U.S. 189. Along the way is the 607-foot Bridal Veil Falls. Entirely paved, the scenic drive is open from about late May to late October; snow closes part of the road the rest of the year. The drive is not recommended for vehicles and trailers over 30 feet long.

(click for larger maps) |

The nearly one million acres of the national forest surrounding the park offer many ways to relax and enjoy the wild outdoors of the Wasatch mountains. In American Fork Canyon alone there are several national forest campgrounds and picnic areas. For hikers and horseback riders there are trails where panoramic vistas, natural lakes, and wildlife such as mountain goats, mule deer, and golden eagles are seen. Two hiking trails ascend to the summit of 11,750-foot Mt. Timpanogos. At Cascade Springs a ½-mile-long boardwalk leads out over clear natural pools and cascading terraces of travertine deposited by springwaters.

Tibble Fork Reservoir, other reservoirs, and mountain streams are popular places for fishing for rainbow and brown trout. Winter is ideal for cross-country skiing and snowmobiling.

Three Utah state parks are nearby. At Wasatch Mountain State Park, on the forested slopes of the Wasatch Range, there are campgrounds; picnic areas; trails for hiking, cross-country skiing, and snowmobiling; and a golf course. At Deer Creek State Park, also in the Wasatch Range, boating, sailing, sailboarding, and fishing for trout, perch, and bass are popular pastimes. Deer Creek also has a campground and picnic areas.

Both Wasatch Mountain and Deer Creek state parks are east of Timpanogos Cave; take Utah 92 to U.S. 189. Utah Lake State Park, located southwest of the park in Utah Valley, features one of the West's largest natural freshwater lakes. Activities include boating. sailing, and fishing for white bass, bluegill, and crappie.

For a Safe Visit

The National Park Service wants you to have a safe visit and to assist in

protecting the park's valuable resources. Please follow these regulations and

tips. • Come prepared for the season. In the summer high temperatures are

usually in the 80s° and 90s°F; evening temperatures may drop to the

50s°. If a sudden thunderstorm occurs, avoid open areas and tall trees prone

to lightning strikes. In spring and fall high temperatures average in the

60s° and lows in the 40s°. In winter high temperatures range from the

20s° to the 40s°, and several feet of snow may accumulate. • Build

fires only in picnic areas and only in grills provided or campstoves. •

Dispose of trash properly. • Do not disturb any animals or plants. Hunting

is illegal. • Utah 92, the main road through the park, is narrow and has

sharp curves: don't exceed posted speed limits; watch for pedestrians crossing

the road or walking alongside. • Pets must always be leashed. • See

above for safety and regulation information concerning a trip to the caves.

• Help us protect and preserve the monument by not collecting or taking

home any plants, animals, or minerals.

Source: NPS Brochure (2010)

|

Establishment

Timpanogos Cave National Monument — August 10, 1933 (NPS) |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Annotated Checklist of Vascular Flora, Timpanogos Cave National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR-2009-167 (Walter Fertig and N. Duane Atwood, February 2009)

Cultural Resources Management Plan: Timpanogos Cave National Monument (1984)

Flowering Plants of American Fork Canyon, Timpanogos Cave National Monument (Eva M. Kristofik, December 11, 1998)

Foundation Document, Timpanogos Cave National Monument, Utah (October 2016)

Foundation Document Overview, Timpanogos Cave National Monument, Utah (January 2016)

General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Timpanogos Cave National Monument (August 1993)

General Management Plan/Development Concept Plan/Interpretive Prospectus, Timpanogos Cave National Monument (September 1983)

Geologic Map of Timpanogos Cave National Monument, Utah NPS Natural Resource ()

Geologic Resource Evaluation Report, Timpanogos Cave National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2006/013 (July 2006)

Geologic Resources Inventory of Our National Parks: A Case Study of the Timpanogos Cave National Monument USGS Open-File Report 2010-1335 (Ronald D. Karpilo, Jr., Stephanie A. O'Meara, Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, Heather I. Stanton and James R. Chappell, from "Digital Mapping Techniques '09-Workshop Proceedings," 2010)

Geological Factors of Timpanogos Cave (Thomas A. Walker, extract from Zion-Bryce Nature Notes, Vol. 6 No. 4, July-August 1934)

Heart of the Mountain: The History of Timpanogos Cave National Monument (Cami Pulham, c2009)

Hydraulic Modeling of Low Flows American Fork Creek, Timpanogos Cave National Monument, Utah (Michael W. Martin and William L. Jackson, Draft, May 19, 1997)

Integrated Upland Monitoring in Timpanogos Cave National Monument: Annual Report 2009 (Non-sensitive Version) NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR—2010/391.N (Dana Witwicki, October 2010)

Integrated Upland Monitoring in Timpanogos Cave National Monument: Annual Report 2010 (Non-sensitive Version) NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR—2012/526.N (Dana Witwicki, January 2012)

Integrated Upland Monitoring in Timpanogos Cave National Monument: Annual Report 2011 (Non-Sensitive Version) NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR—2013/714.N (Dana Witwicki, March 2013)

Junior Cave Scientist Activity Book (Ages 5-12+) (2016; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Activity Book, Timpanogos Cave National Monument (2009; for reference purposes only)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Timpanogos Cave National Monument (December 2010)

Macroinvertebrates of Timpanogos Cave, Timpanogos Cave National Monument, Utah Final Report 2003 (C. Riley Nelson, Julie Guptill and Richard W. Baumann, May 17, 2004)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Timpanogos Cave Historic District (Mary Shivers Culpin, February 10, 1982)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Timpanogos Cave National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/TICA/NRR-2020/2188 (Catherin A. Schwemm and Donna Shorrock, November 2020)

Park Newspaper (Timpanogos Reflections): Summer 2004 • Fall-Winter 2004 • Summer 2005 • Summer 2006 • 2010 • 2011 • 2012 • 2023

Reconnaissance Geology of Timpanogos Cave, Wasatch County, Utah (William B. White and James J. Van Gundy, extract from NSS Bulletin, Vol. 36 No. 1, January 1974; ©The National Speleological Society)

Resource Review: Spring 2004 • Summer 2004

Science & Resource Management 2004 (c2004)

Science & Resource Management 2005 (c2005)

Statement for Management — Timpanogos Cave National Monument: April 1984 • August 1986 • April 1989 • August 1989 • July 1991

Timpanogos Cave National Monument Visitor Study: Summer 2005 Visitor Services Project Report 167 (Marc F. Manni, Yen Le and Steven J. Hollenhorst, February 2006)

Trail Guide: Wildflowers of Timpanogos Cave National Monument (Becky Peterson and Brandon Kowallis, 2004)

Trees of American Fork Canyon, Timpanogos Cave National Monument (Eva Kristofik, December 16, 1998)

Trends in Water Quality of Cave Pools at Timpanogos Cave National Monument, July 2008–September 2018 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NCPN/NRR—2020/2181 (Rebecca Weissinger, Andy Armstrong, Kirsten Bahr and Chris Groves, October 2020)

Vascular Plant Species Discoveries in the Northern Colorado Plateau Network: Update for 2008-2011 NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR-2012/582 (Walter Fertig, Sarah Topp, Mary Moran, Terri Hildebrand, Jeff Ott and Derrick Zobell, May 2012)

Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report, Timpanogos Cave National Monument NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCPN/NRTR-2009/210 (Janet Coles, Jim Von Loh, Aneth Wight, Keith Schulz and Angie Evenden, April 2009)

tica/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025