|

Tupelo National Battlefield Mississippi |

|

NPS photo | |

Soldiers! Amid your rejoicing do not forget the gallant dead upon these fields of glory. Many a noble comrade has fallen, a costly sacrifice...The most you can do is cherish their memory.

—Nathan Bedford Forrest

The Battle of Tupelo, July 14-15, 1864

For Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman the fighting in Mississippi in summer 1864 had only one purpose: to protect the railroad carrying food and ammunition from Louisville, through Nashville and Chattanooga, to his army advancing on Atlanta. So important was this to Sherman that after the Battle of Brices Cross Roads he ordered his commander in Memphis "to make up a force and go out to follow Forrest to the death, if it cost 10,000 lives and breaks the Treasury."

Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, as Sherman wrote, had "whipped Sturgis fair and square, and now I will put against him A.J. Smith. . . ." So, on July 5, 1864, Maj. Gen. Andrew J. Smith marched into northern Mississippi with over 14,000 men in a dust-choked column nearly 15 miles long, fighting and skirmishing along the way. Both Maj. Gen. Stephen Lee, commanding the Confederate Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana and Forrest knew Smith would try to bring the Confederates to battle. Both believed their best move would be to await an attack in a strongly fortified position. They chose Okolona, 18 miles south of Tupelo, for their defensive line. But in order to prepare a strong position, troops had to be drawn to Okolona from throughout northern Mississippi. On July 13, his cavalry having learned that Tupelo was now unprotected, Smith marched his Federal forces in that direction. By taking the town he believed that he would both gain a hold on the Mobile & Ohio Railroad and force the Confederates to attack him—in a fortified position.

Realizing what was happening, Forrest hurried up his main force to attack the long Union column. Smith's soldiers beat back the attacks and marched on, reaching the little village of Harrisburg (now in the Tupelo city limits) about dark the same evening. Here they camped, forming a battle line along the crest of a low ridge, and awaited the attack they expected the next day. Lee did not plan to disappoint them. As he told Forrest, Smith's army must be "dealt with vigorously at at once."

The Battle of Tupelo in Brief

The battle began here at 7:30 am, as Confederates started a series of uncoordinated charges against the Federal position. The attacks were easily beaten back with heavy losses. Failing to break the Federal center, the Confederates attacked the Federal right flank, again without success. That attack was followed by a Federal counterattack that quieted the Southerners temporarily. After dark on July 14, the Confederates made another attack from the south without significant effect.

His troops had repulsed several Confederate attacks, but General Smith was alarmed. The heat took its toll on his soldiers, and, due to bad planning, his men had little but coffee and worm-infested hardtack to eat, and their ammunition supply was distressingly low. At 2 pm on July 15, after skirmishing with Confederates on the western and southern fronts, the Federals began marching north toward Memphis. They marched four miles, crossed to the north side of Old Town Creek, and camped in late afternoon.

A t 5 pm on July 15, from a commanding ridge south of Old Town Creek, Confederates surprised Smith's troops with artillery and infantry fire. The Federals scrambled to form a line that pushed the Confederates off the ridge, forcing their retreat to Harrisburg. The Old Town Creek fight ended the Battle of Tupelo, with many casualties on both sides. Forrest himself sustained a temporarily disabling wound keeping him out of action for three weeks.

Aftermath

Neither side could claim complete victory. Lee and Forrest could say that Federal forces turned back after the battle, but the Confederates had not fought with their usual skill. Forrest's soldiers "went in by piece-meal and were slaughtered by wholesale," a Confederate officer wrote years later. The attacks, Smith reported, "were gallantly made, but without order, organization, or skill."

Smith did not follow Forrest "to the death" but held him for a time. Sherman gave Smith credit for that, sending him out to fight Forrest again in August. And again Smith kept Forrest in Mississippi, away from Sherman's supply route. In September, Forrest rode into Tennessee, and his men saw hard service but with no effect on the war's outcome. Sherman—now beyond Atlanta and beyond the railroad—was cutting through Georgia on his "march to the sea."

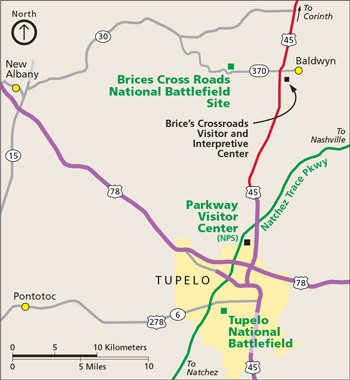

(click for larger map) |

U.S. Colored Troops at Brices Cross Roads and Tupelo

As the Emancipation Proclamation took effect January 1, 1863, former slaves and free black men could volunteer for U.S. military service. Formed into regiments commanded by white officers, these men were called the United States Colored Troops (USCT). Several USCT regiments commanded by Col. Edward Bouton played critical roles in the battles of Brices Cross Roads and Tupelo.

At Brices Cross Roads, Bouton's regiments, held in reserve until Forrest's troopers soundly defeated the Federal forces, made several critical stands that slowed the Confederate pursuit of the Federal retreat.

Before the Battle of Tupelo the USCT protected the supply train and served as rear guard for the Federal army. The USCT held off several Confederate attacks, which allowed the Federals to secure the most advantageous ground for the battle of July 14-15.

Visiting the Battlefield

Tupelo National Battlefield is on Main St. (Hwy. 6) in Tupelo, 1.2 miles east of the Natchez Trace Parkway. National Park Service interpreters at the Parkway Visitor Center near Tupelo provide information about both battles (Tupelo and Brices Cross Roads).

Source: NPS Brochure (2016)

Documents

Foundation Document Overview, Natchez Trace Parkway, Mississippi/Alabama/Tennessee (December 2014)

Master Plan Development Outline, Tupelo National Battlefield Site (1952)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Tupelo National Battlefield (William E. Cox, October 1, 1974)

Protecting Sherman's Lifeline: The Battle of Brices Cross Roads and Tupelo 1864 (Edwin C. Bearss, 1971)

State of the Park Report, Natchez Trace Parkway (incl. Natchez Trace National Scenic Trail, Brices Cross Roads National Battlefield Site and Tupelo National Battlefield), Alabama-Mississippi-Tennessee State of the Park Series No. 31 (2016)

The Tupelo Campaign: June 22-July 23, 1864 — A Documented Narrative & Troop Movement Maps (Edwin C. Bearss, May 15, 1969)

tupe/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025