|

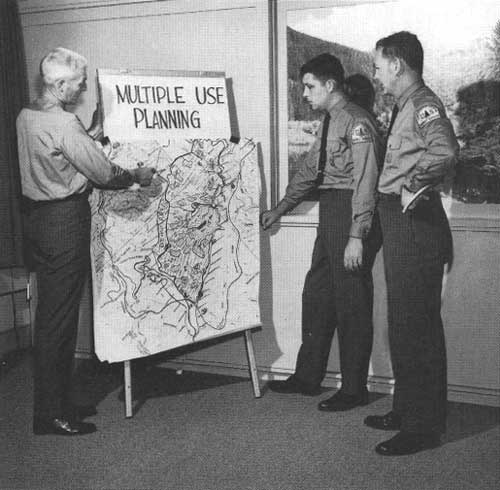

Managing Multiple Uses on National Forests, 1905-1995 A 90-year Learning Experience and It Isn't Finished Yet |

|

Chapter 3

Managing Multiple Uses in the Face of Unprecedented National Demands: 1945 to 1970

National Forest Planning and Performance: 1945 to 1970

Rapid economic and population growth after World War II created extraordinary demands on the goods and services of the Nation's natural resources. National forests quickly became a major source for expanding the supply to meet those demands. National forest managers were immediately challenged to rebuild and expand their workforces, access roads, facilities, and equipment. They also had to make up for the maintenance and management deferred through the war years and deal with the rapid growth in resource demands that outran and continually taxed their managerial capabilities and workforces.

In the 25 years from 1945 to 1970, national forest timber harvesting rose an average of more than 5 percent per year — twice the rate of the national economic growth and almost four times faster than total U.S. production of industrial wood products. During the 1950's and 1960's, national forest timber and the expansion of low-cost Canadian lumber imports offset a near 40 percent decline in the South's average annual softwood lumber production (Ulrich 1989). National forest timber stabilized log supplies for the large and highly productive timber industry of western Oregon and Washington and increased total log supplies for the rest of the West (Fedkiw 1964). The large and rapid increase in national forest timber harvests contributed to the economic stability and growth of many western communities and helped meet national housing goals and lumber demands. They also relieved pressures to harvest the stands of young, small-diameter timber. This gave the South's young and rapidly growing southern pine trees a 20-year opportunity to grow in size and increase the South's timber inventory.

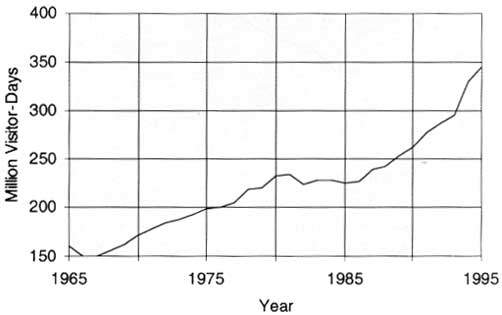

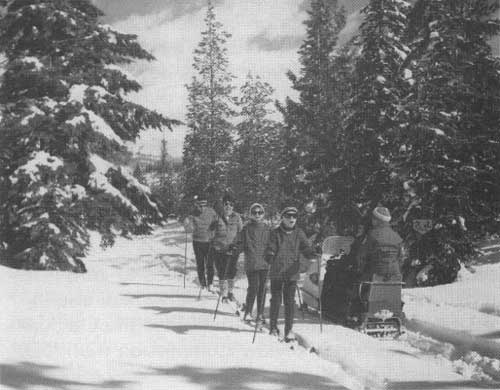

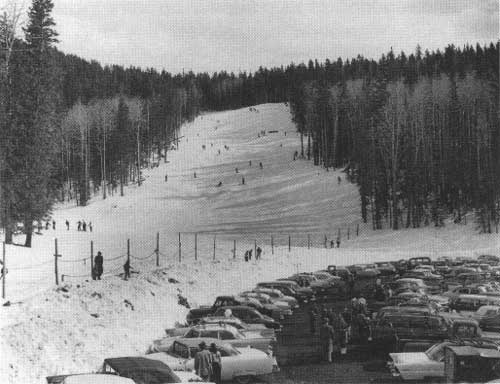

Recreation visits to national forests grew more than 11 percent per year — more than 6 times faster than population growth — as the American family's income and leisure time increased and the Nation's highways and transportation facilities greatly expanded and improved. Hunting and fishing visits rose at an even faster rate. Water-storage facilities for power, irrigation, domestic consumption, mining, fisheries, and recreation use increased by about a million surface acres. Mineral exploration and development grew sporadically, but steadily.

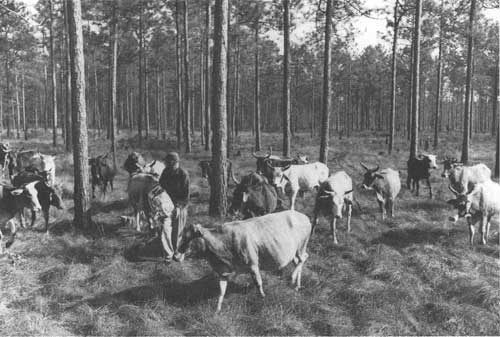

Beef consumption, nationally and per person, also increased steadily during this period. National forest cattle grazing rose from 1.2 million to 1.5 million AUM's — an increase of 25 percent. Forage productivity improvements and the acquisition of the national grasslands brought a 30-percent increase in grazing allotment carrying capacities. Animal husbandry improvements and improved range forage added significantly to cattle weights. However, there was a significant decline in sheep herding and grazing.

National forest area dedicated to wilderness use increased by 7.1 million acres, from less than 1.5 million acres to 9.1 million in 1964. The National Wilderness Preservation Act of 1964 included these wilderness acres as the initial components of the National Wilderness Preservation System. An additional 5.5 million acres were scheduled for evaluation and eventual wilderness designation over the next 10 years. Nearly a million of those acres were added to the National Wilderness Preservation System by 1970.

There was an evolution in planning and management for multiple uses on national forests during this period. The fitting of multiple uses into ecosystems on individual national forests became increasingly complex as demands for all national forest uses burgeoned. The fitting of adaptive management practices for overlapping and adjacent resource uses into the site-specific conditions within highly variable ecosystems became more challenging. Reconciling competing and overlapping user interests likewise became more demanding, especially as those interests broadened beyond local users to regional and national publics and special-interest groups. Conflicts between the timber industry and wilderness and recreation interests reached national proportions.

During the early years and into the 1950's, planning on national forests focused on individual resources such as timber, rangeland, recreation opportunities, wilderness areas, wildlife and fish, and watersheds. Planning called for inventories of resource conditions and trends on rangelands, forests, watersheds, recreation sites, and wildlife habitats. Planning determined sustainable timberland and rangeland use levels and assessed the need to modify use or adapt management in areas where there was a need to protect watersheds and other resources. The collection and evaluation of resource data for national forest planning grew throughout the 1945 to 1970 period. The data reflected both the use and the condition of natural resources.

|

| Multiple use: timber growth and harvest and mineral development. Lakeview Logging Company truck hauls harvested logs, Fremont National Forest, Oregon, 1960. The derrick in the background is part of a Humble Oil Company wildcat operation searching for oil or natural gas. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by Paul R. Canutt.) |

Conflicts were largely avoided or easily mitigated as long as the level of use remained relatively low compared to the national forests' capacity to absorb it. Where conflicts did occur, a multifunctional consultation approach was used to coordinate the uses. Users and State and local wildlife and water resource officials often helped resolve these issues.

National forest efforts to coordinate land uses through management planning became more deliberate as resource uses accelerated during the 1950's. Local managers began to demarcate recreation and special management areas, waterways, roads and trails, and other use characteristics in their plans as resource inventories were completed. The content of these plans differed from forest to forest because the National Forest System had no uniform standards or direction for coordinating multiple uses. Despite this lack of consistency, more informed planning and management decisions were being made. However, the actual implementation of the decisions on the ground in many instances still depended on the district ranger's or forest supervisor's practical experience and intuitive judgment (Wilkinson and Anderson 1985).

The Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act (MUSY) in 1960 brought a more balanced consideration of all national forest uses and resources. MUSY mandated that national forests be managed for multiple uses and sustained yield of their products and services; that the various renewable surface resources be used in combinations that best met the needs of the American people; and that the relative values of the various resources be considered and that decisions not be limited to use combinations that gave the greatest dollar return or the greatest unit output.

The Forest Service proposed the MUSY Act when pressures were emerging from the timber industry and wilderness interests, respectively, to increase and to halt the harvesting of remaining old-growth stands. The wilderness interests largely perceived old-growth timber lands as "the" remaining wilderness. They saw the construction of national forest roads to access old-growth timber as rapidly reducing wilderness designation options. The Forest Service felt that legislative direction to manage national forests for multiple uses and sustained yields would provide the policy guidance to ensure a nationally balanced mix of uses in the face of the opposing pressures of "single-interest groups" and economic demands for possible "overuse" (USDA Forest Service 1961b).

|

| Brahma hybrid cattle grazing under permit on wiregrass forage in a managed stand of longleaf pines, Apalachicola National Forest, Florida. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by Dan Todd.) |

Diversifying Staff and Skills in Managing Growing Multiple Uses

This period saw an improvement in natural resource science, knowledge, technology, and professional skills. For example, the number of degrees conferred annually in natural resource areas rose from an estimated 10,000 to 15,000 in 1940 to more than 60,000 around 1970, and for the first time around 1970 included a significant number of women. For the same period, the number of doctorates in natural resources subjects rose from 12 in 1940 to 122 in 1970. Membership in natural resource professional societies rose from 6,300 to 47,400 (Fedkiw 1993).

The Forest Service increased both the number of resource professionals in the national forest work-force and the diversity of their knowledge and skills as resource use and management became more complex and the supply of professionally trained resource specialists expanded. Although foresters continued to dominate the professional workforce, the diversity of skills and knowledge within the national forest workforce in the early 1970's grew (table 1) (Fedkiw 1981).

Table 1. Number of Forest Service employees by occupation and skill, 1972

| Occupation or Skill | Number |

| Forester | 5,021 |

| Civil Engineer | 1,081 |

| Range Conservationist | 262 |

| Contracting and Procurement | 239 |

| Landscape Architect | 181 |

| Soil Scientist | 151 |

| Wildlife Biologist | 108 |

| Hydrologist | 104 |

| Plant Pathologist | 94 |

| Computer Specialist | 92 |

| Geologist | 52 |

| Fisheries Biologist | 24 |

| Archaeologist | 4 |

| Geographer | 3 |

| Economist | 2 |

| Total | 7,418 |

Source: USDA Forest Service 1980. | |

Although these skills had been previously represented in the Forest Service, they were almost exclusively in Forest Service Research and in Washington and the regional offices. Now they were increasingly needed on national forests and ranger districts.

Depth of experience and seasoned judgment from working with a wide range of forest conditions, uses, and users on the ground were important supplements for managing natural resources effectively. Multidisciplinary consultation expanded and helped integrate the management of multiple uses. But the driving force of annually expanding use "targets" and management challenges in each individual resource area continued to influence the seeking of resource-specific solutions. Advanced planning and longer lead times became increasingly critical tools for the effective integration of multiple uses and their management.

|

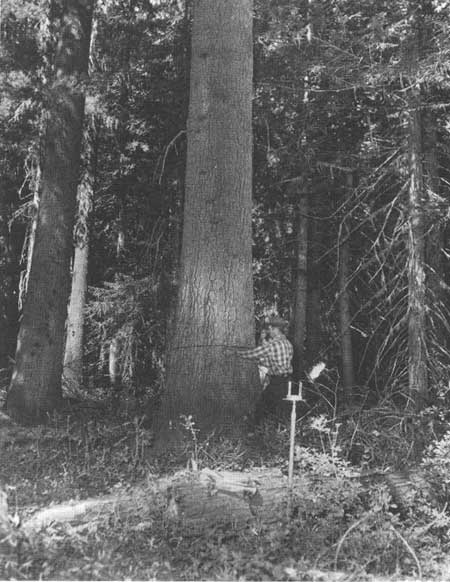

| Managing for multiple uses on the Dale Ranger District, Umatilla National Forest, Oregon, 1960. Range cattle grazing, timber production, water supply and fish habitat. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by C.M. Rector.) |

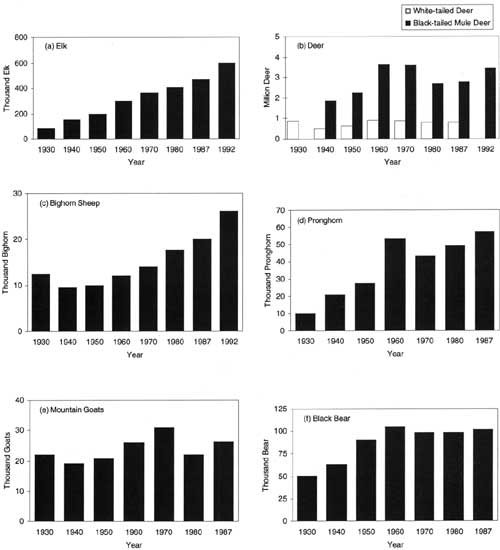

In this general setting, national forest managers met expanding output and use targets while advancing the art, practice, and effectiveness of managing multiple uses. Although there were shortfalls along the way, national forest outputs and uses rose to peak levels in the 1960's. Wildlife and fisheries habitats, particularly for game species and specifically targeted species, such as the condor, Kirkland's warbler, and osprey, were generally being maintained or improved. Eastern national forests were being rehabilitated. Rangeland conditions were being improved and forage production was increasing. Forest fires were being contained to lower acreages and other natural disasters were being ameliorated. There were more research natural area and wilderness designations. The quality of managing multiple uses improved incrementally, but slowly, responding to growing uses as well as improving science and management skills. National forest managers gave new attention to wetlands and increased their efforts to identify and take measures to protect endangered species and their habitats.

National forest management's incremental responses to the growing and changing mix of multiple uses were progressively building, extending, and modifying use systems throughout the National Forest System, and during this period incremental responses seemed sufficient. The National Forest System was progressively evolving into an integrated association of uses and management systems that were designed to sustain the uses and ensure the permanence of the resources and their productivity. The individual use systems became more integrated as they increasingly overlapped and adjoined each other in various combinations within the national forests. During the 1950's and 1960's, national forest managers modified and adapted the forest structures and their ecosystems as they provided Americans with increasing quantities of products, services, and benefits from water, timber, mineral, range, wildlife, fishery, watershed, recreation, landscape, and wilderness resources.

However, major events and uncertainties during the 1960's began to reveal serious management inadequacies and dissatisfactions among some national forest users and important groups of the American people.

Public concerns for wildlife management, for example, began to develop broader and deeper dimensions. Game biologists and some hunters questioned the knowledge and practices used to manage elk throughout the Rocky Mountains. Using timber harvest to improve food and forage supplies, controlling excess livestock and big game numbers, and protecting big game winter range did not always sustain desired deer and elk population levels or quality hunting experiences. This issue came into sharp focus when Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks biologists challenged a proposed timber sale on the Lewis and Clark National Forest. National forest managers saw the sale as a necessary part of the Forest's timber management program. The biologists anticipated an adverse impact on elk that would shift game populations from State-owned lands to private lands. To resolve this dilemma, national forest managers joined several Federal and State wildlife agencies in a long-term study of elk habitat requirements (Lyon et al. 1985).

In the East, national forest users on West Virginia's Monongahela National Forest questioned the way even-aged management was being applied to hardwood forests. Such forests provided important turkey and squirrel habitats and long-established, highly valued hunting grounds. National forest users also questioned the visual impacts and quality impairments associated with clearcutting. After several years of challenges from the West Virginia Legislature and national forest users, the Monongahela prepared an environmental impact statement (EIS) on the forest's implementation of even-aged timber management. The Forest recognized the need for management changes and improvements and generally agreed with the findings of a study commission established by the State Legislature. The EIS recommendations, if they could be effectively implemented, indicated that the Monongahela's timber management questions could be resolved, but the issue actually broadened in the early 1970's.

During the 1960's, the public became aware that populations and habitats of some wildlife, fish, and plants were declining, including wetland habitats for waterfowl. National forest managers, responding to these emerging concerns, began to increase their efforts to protect and restore wetlands and to identify and address endangered species habitat needs jointly with various interest groups and public agencies.

In the West, national forest managers realized that forest fire prevention and control were leading to a new problem — forest fuel buildups. They began to address this concern through fuel inventories and fuel hazard management projects that used prescribed burning to reduce fuel buildups and strategically located firebreaks to slow and control fires that might break out in areas of heavy fuel and high risk.

National forest managers, seeing a need for better soil inventories and soil management capabilities, initiated soil surveys and a related soils training program. The soil surveys were barely underway in 1964 when a massive landslide occurred in the watershed of the South Fork of Idaho's Salmon River. A combination of extraordinary rainstorm conditions and extremely wet soils on steep and unstable slopes, which for decades had been crisscrossed by logging roads, were seen as the cause. These conditions led to severe sedimentation of the river and its tributaries, with devastating damage to salmon fisheries and habitat — particularly spawning beds.

In Montana, local citizens were relentlessly challenging clearcutting and terracing on the Bitterroot National Forest's steeper, more visible mountain slopes. The issue became national in 1970's.

Internally, the Forest Service was using the traditional incremental management response to local demands, issues, and problems — a style that had worked well in addressing natural disasters and catastrophic forest fire conditions. National forest managers felt that shortfalls, failures, or new problems that involved management, as well as natural events, could be ameliorated or reversed using this same approach. Believing this, they took care to define and limit matters to their local dimensions. Implementation of System-wide initiatives such as fuel hazard management and soil surveys was largely left to the regions and forests according to what they perceived were their local priorities and preferred timeframes.

The Forest Service's hierarchical administrative structure and decentralized style of managing multiple uses continued to prevail during this period — even though national forest managers were becoming more aware of the public's growing concerns about the direction and quality of national forest management. No comprehensive effort emerged within the Forest Service or USDA to integrate these major events and concerns into an holistic evaluation of the National Forest System's performance. Although there were a few individual exceptions, the national forest management hierarchy did not generally perceive this traditional hierarchical and decentralized approach to managing multiple uses as a potential weakness or "Achilles heel" in managing national forest lands.

The next part of chapter 3 describes the development and growth of multiple uses on national forests and the efforts to improve resource protection, maintenance, and management in meeting the demands of the American people from 1945 to 1970. Each resource is described separately because that is the way use was managed and reported. The growing need for planning and coordinating the management of multiple uses is given special emphasis.

The Management of Multiple Uses: 1945 to 1970

Population, Economic, and Demand Trends

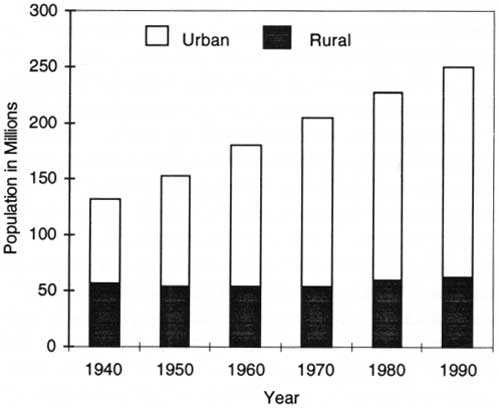

From 1945 to 1970, the American population grew by 45 percent, from 64 million to 205 million — an increase unmatched before or since. The economy rose almost twice as fast as population and led to substantially improved per capita incomes and family welfare. Leisure time and mobility likewise increased. There were also major shifts in regional demographics as Americans sought to share in the Nation's economic growth by relocating to areas of growing employment and higher wages. Urban populations rose from 60 percent to 74 percent of the Nation's population, while rural populations declined to 26 percent (fig. 5). Agricultural productivity per acre and per farmer rose rapidly and induced younger people to out-migrate from rural areas. Even though national growth became concentrated in urban and suburban communities, agriculture and natural resource development prospered.

|

| Figure 5. U.S. urban and rural population, 1940-1990. Source: Bureau of the Census, U.S. Department of Commerce. |

Between 1940 and 1970, the number of households nearly doubled, from 35 million to more than 63 million. Construction of new housing rose to an average of a million homes per year. The need for replacement housing rose from 100,000 units per year in the 1930's and early 1940's to 700,000 units per year in the 1960's. Lumber and plywood consumption rose from 32 bbf in 1945 to 44 bbf in 1950, an increase of 40 percent, and to 50 bbf by 1970, 57 percent more than in 1945. Beef consumption more than doubled to a peak level in 1976. Cattle numbers rose from 86 million head in 1945 to 132 million by 1976.

Outdoor recreation activities accelerated faster than the population growth. Recreation use on Federal lands soared. Manufacturing, construction, energy use, and urban development also expanded more rapidly and produced great increases in emissions, effluents, and wastes that increasingly impacted the Nation's air, water, and land for their dispersal and disposal. Rapid growth in every dimension of society brought unprecedented demands on the goods and services provided by the Nation's natural resources. National forests quickly became an expanding source of supply for meeting those demands.

|

| Forest supervisor and district ranger inspecting conditions in Big Whitney Meadows, Inyo National Forest, California, 1958. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by Daniel O. Todd.) |

Grazing Use and Management

In 1945, some 23,000 ranchers and farmers were grazing 1.2 million cattle and 4.3 million sheep and goats on national forests. This stocking level was 45 percent below the severe overstocking of ranges during World War I and closer to range carrying capacity. But seriously degraded vegetation, eroded soil, and other unsatisfactory range conditions remained (USDA Forest Service 1945; Rowley 1985). Although World War II production pressures had also slowed efforts to reduce livestock numbers, livestock producers after the war were prepared to resist renewed efforts to reduce the number of animals they could graze. Cattlemen and sheepowners were resolved to work together to achieve vested rights (established entitlements) to their allotments, clarify grazing objectives, and strengthen their role in managing their livestock on national forest allotments.

As the public became more aware of this issue, national forest managers became more sensitive about letting unsatisfactory range conditions continue. The general press and conservation groups strongly opposed any increased grazing on Federal lands and supported national forest initiatives for further livestock reductions and range betterment (Rowley 1985).

Despite stockowners' opposition, the Forest Service renewed its emphasis on reducing stock levels. Both stockowners and national forest field employees recognized the challenges in implementing such reductions. They did not agree on methods for estimating grazing carrying capacity or range conditions and trends. Some field employees complained that "We just do not have reliable records of conditions measured periodically from which trends can be determined" (Rowley 1985). Range rehabilitation was recognized as easier to implement and more acceptable to stockowners, but it was a slower process. Between 1933 and 1945, western national forests reseeded 85,000 acres of rangeland, while 45,000 acres of pastured lands were reseeded on eastern forests. This was a start, but 4.2 million acres needed reseeding. To accelerate range rehabilitation, Congress in 1949 authorized $3 million to develop nurseries to grow grass and shrub seed to reseed depleted rangelands and restore their forage and browse cover. The Forest Service also began to explore easily demonstrated ways to measure range vegetation conditions and trends (Rowley 1985).

The Granger-Thye Act of 1950 provided for the use of legally authorized 10-year grazing permits and local grazing advisory boards. It also authorized the use of grazing receipts when appropriated by Congress — 2 cents per AUM for sheep and goats and 10 cents per AUM for other stock — for reinvestment on the national forest rangelands for reseeding; constructing fences, stock watering places, bridges, corrals, driveways and other improvements; controlling range-destroying rodents; and eradicating poisonous plants and noxious weeds.

|

| District ranger with permittee inspecting range conditions and cattle grazing under permit on an allotment in the Tatoosh Mountain range, Gifford Pinchot National Forest, Washington, 1949. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by L.J. Prater.) |

Between 1945 and 1955, cattle numbers on national forest rangelands were reduced by 9 percent and sheep numbers by one-third. Range permittees declined by 10 percent to 21,000. The sharp decline in sheep grazing was strongly influenced by market factors such as the advent of synthetic fabrics and a one-third reduction in U.S. wool and mohair production. Wool imports declined even more, by 60 percent, reflecting a sharp drop in market demand. The cattle industry, however, grew as beef consumption steadily rose to a peak in the mid-1970's. Cattleowners, thus, continued to strongly oppose reductions in permitted livestock.

The Granger-Thye Act did not grant the vested rights sought by permittees. Permits remained contract privileges rather than absolute rights. The new legal status given local grazing advisory boards encouraged stockowners to participate more actively in negotiating the terms of their grazing contracts. Grazing advisory boards were made up of 3 to 12 stockowners who were also national forest grazing permittees — and could include a representative of wildlife interests appointed by the State game commission. When requested to do so by a permittee, the boards could provide national forest managers with advice and recommendations on grazing permit modifications, animal reductions, or denials for permit renewals. The boards also advised on establishing or modifying individual or community allotments. The Granger-Thye Act brought stockowners some relief from the policy for reducing permitted stock as national forest range management increased its emphasis on improving and expanding forage production to avoid future reductions (Rowley 1985).

In this environment, national forest rangeland management shifted away from aggressive reductions and emphasized range improvements to increase forage production. Stockowners strongly supported and cooperated with this shift. They increasingly participated in improvement projects with money, time, labor, and materials. The pace of reseeding, fencing, installing water developments, and building livestock driveways accelerated after 1955. In addition to increasing forage productivity and output, these range improvements also helped correct some of the longer term problems of deteriorating and depleted ranges. Cattle numbers in 1970, compared to 1955, were up about 31 percent to 1.5 million, and range carrying capacity was up by 30 percent. Half of the increase in capacity was due to the addition of the national grasslands in 1954. With this shift in management emphasis, the aggressive drive for livestock reductions faded. But national forest managers made it clear to stockowners and their political representatives that such reductions were still needed on the more critical lands. Sheep numbers declined to 1.7 million by 1970 and allotment permittees dropped below 18,000 by 1970. When allotments were no longer needed for sheep, some were converted to cattle allotments.

National forest grazing managers installed an allotment analysis system using improved methods and measures for assessing range conditions and trends developed by research in the mid-1950's. Permittees were encouraged to participate in allotment analyses and planning. They also began to hire range scientists to do independent range studies for their own interests. By 1960, allotment analyses had been completed on a third of the 11,000 national forest allotments. Some 1,900 — more than 17 percent — had plans based on these analyses. In 1965, grazing permittees became cosigners of their 10-year permits. By 1970, the first cycle of systematic range analysis and planning had been completed on all allotments. Range rodent and noxious weed control also advanced during this period (USDA Forest Service 1945-1970; Rowley 1985).

Stockowners introduced improved breeds and animal breeding during this period. These improvements, together with greater forage production and higher forage consumption per animal, increased the number of cows calving and overall stock weight, a performance difficult to quantify, but nevertheless an observed benefit of better animal husbandry and range betterment.

Grazing on southern national forests was free until 1965. Because the southern forests had been acquired through piecemeal purchases of farmland, their progress in range management had been slow and difficult. Long-established customs and free use of open range reinforced the reluctance of local stockowners to accept regulated grazing. Poor economic conditions in the more remote rural South also slowed progress. In 1965, however, when cattle grazing was expanding with growing beef demands, grazing fees were introduced on southern forests.

Stockowners Sensitive to 1960 Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act

The MUSY Act in 1960 specifically identified range as a resource use, along with outdoor recreation, timber, wildlife, watershed, and fish, among the national forest multiple-use purposes. Although the Act explicitly authorized range use in law for the first time, the livestock industry perceived a threat from this affirmation. The industry became particularly sensitive to recreation use, including wilderness, as a competitor to traditional grazing privileges. The emergence of the environmental movement during the 1960's and early 1970's similarly raised stock-owner and range manager concerns, as environmental groups began to perceive national forest range managers as being too closely allied with range users and livestock organizations. These unfolding sensitivities were indicative of changes to come in the 1970's and later.

The National Grasslands

In 1954, the administration of 3.8 million acres of rangeland land utilization projects (LUP's) was transferred from the Soil Conservation Service (SCS) to the Forest Service. The SCS had originally acquired these lands, primarily in the Great Plains Region, and managed them for domestic livestock grazing during the depth of the Depression under a New Deal program designed to purchase unprofitable, low-productivity farmlands for Federal administration. In 1960, the Secretary of Agriculture designated almost all of these lands as 19 national grasslands and formalized their management by national forest managers (Rowley 1985). NFMA formally incorporated the national grasslands into the National Forest System in 1976.

The national grasslands brought new challenges to national forest managers. The Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act, as amended in 1963, required that their management promote grassland agriculture and sustained-yield management and demonstrate sound land use practices to adjacent public and private landholdings. During its 20 years of management, the SCS had established cooperative agreements with Great Plains grazing associations and districts to help integrate the management and use of LUP grasslands with the needs of the private operators who leased them. The SCS issued permits to the associations, which, in turn, redistributed grazing privileges among their members according to the overall grazing limits. The associations often participated in planning and design of LUP improvements. This participative and coordinated approach to rangeland husbandry was in stark contrast to the national forests' direct control of rangeland management. National forest managers, nevertheless, accepted the challenge and eventually acceded to much of the SCS approach and practice in grassland management. As grassland managers and technical assistants assigned to the national grasslands transferred to range positions elsewhere on the National Forest System, they helped spread the use of cooperative, integrative, and demonstration approaches to other national forest rangelands (West 1992; Rowley 1985).

|

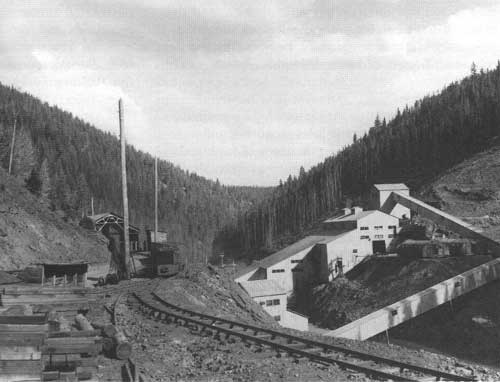

| Blackbird mine operations on Blackbird Creek, Salmon National Forest, Idaho, location of the world's largest cobalt deposit, 1952. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by L.J. Farmer.) |

Managing Surface Resources on Mineral Leases and Claims

The exploration and extraction of leasable minerals (oil, gas, coal, oil shale, phosphate, potassium, and sulfur) on national forests grew steadily in the postwar years as national development and related demands for energy resources expanded rapidly. In the late 1940's, leases — mainly for gas and oil — numbered about 4,000 and covered less than 5 million acres. By 1970, their number had increased to 19,000 and covered 16 million acres — almost 10 percent of all national forest lands. Most of the growth occurred on the former public domain lands in the western national forests and on the acquired lands of the southern national forests. But leasing occurred in all regions.

The BLM had responsibility for administering both mining leases and hardrock mineral claims on national forests created from the public domain. In 1947, the BLM was also delegated the administration of mineral leases and claims on acquired national forest lands. The Department of the Interior's Geological Survey was responsible for technical administration of the leases. The role of national forest managers was to ensure that mineral exploration and development were compatible with national forest surface rights and resources. By interdepartmental agreement between Interior and USDA, this included reviewing applications, recommending approval actions, and stipulating conditions for the protection and use of surface resources.

In reviewing lease applications, national forest managers sought to further mineral development, under conditions that protected the surface resources for timber production, watershed protection, forest recreation, and wildlife and fisheries. In 1951, for example, California's Los Padres National Forest worked cooperatively with BLM, the Izaak Walton League, the Audubon Society, and the oil industry to agree upon a set of special stipulations for all oil and gas leases in the Sespe Condor Sanctuary (USDA Forest Service 1951-1952).

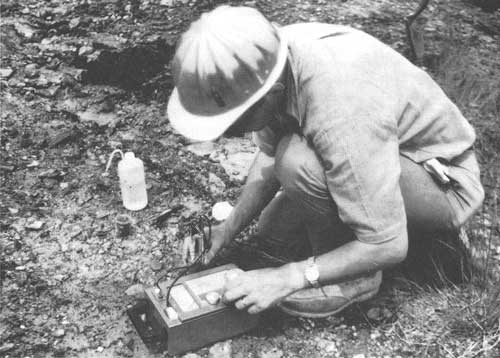

National forest managers reviewed each application to determine whether mineral development and use could be carried out in harmony with surface uses. Where harmonious use was impractical, they assessed the relative values. In the case of strip mining, for example, a determination could be made that the best public interest precluded strip mining altogether in valuable watershed or recreation areas, but could be permitted in other areas. Where such mining would seriously impair the surface resources, a stipulation would be made that, after mining, the operator would restore surface resources for productive use and otherwise prevent soil erosion.

|

| Hydrologist checks pH content of strip mine, Shawnee National Forest, Illinois, 1967. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by Paul Steucke.) |

In 1960, wildlife groups challenged oil and gas interests when the latter applied for leases to explore and develop oil and gas resources on the North Kaibab section of Arizona's Kaibab National Forest. National forest managers worked cooperatively with BLM, the oil industry, the Geological Survey, the State of Arizona, sportsmen, and other conservationists to review lease applications and issue final permits. They jointly developed 35 stipulations to protect wildlife and wildlife user interests. The stipulations controlled the number of wells that could be drilled at any one time; the location, construction, and use of roads; pipeline locations; limits on tanks and other surface uses; disposition of equipment; revegetation measures; and measures to protect scenic, water, wildlife, and other resources. As it turned out, the exploration ended as a "dry hole" (USDA Forest Service 1963-1964). By the end of the 1960's, national forest managers were initiating coordination and protection actions on about 4,000 leases per year.

Mining Claims

Shortly after World War II, the number of people staking spurious claims on national forests under the 1872 Mining Act accelerated. Many claimants intended to use the staked claims for purposes other than mining. The 1872 Act did not provide that mining be done on a claim after it was patented, nor did it provide any checks against damage to soil, timber, water, or other resources. In many places, a finder could still stake a claim by filing a document with the county and marking the site with a note in an old Prince Albert tobacco can. In many counties, there were literally thousands of such questionable claims. The late 1940's and early 1950's became an era of the "weekend miner." Legitimate claims by miners who had actually discovered minerals and were working to develop them were mixed in with spurious claims — making the handling of mining claims a nuisance for national forest managers. Many national forest managers became skeptical and even hostile to mineral development (Peterson 1983).

In the big-timber country of California and the Pacific Northwest, where timber values often far exceeded estimated values of minerals on claims (some timber was valued up to $25,000 per acre), some claimants clearly used the mineral laws to obtain title to that timber. Other claims were used to control access to large bodies of merchantable national forest timber or to develop summer home sites. In many areas, the claimholder's pre-emptory right to surface resources often made effective natural resources management difficult or impossible.

|

| District ranger examining mining claim found in a can nailed to a tree during a forest boundary survey in the Clear Creek area, Boise National Forest, Idaho, 1955. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by Bluford Muir.) |

In the early postwar years, the national forest resource manager's role in mining claims and patents was largely reactive and limited to initiating protests against claims believed to be invalid and those where surface resources were being improperly used. Mining claimants, to hold their claims, had to do a small amount of work on them each year and had the right to use surface resources, but only as needed for such work.

Legitimate mining operations continued to be encouraged, and they increased on national forests. Claimants could obtain patents to bona fide claims under the mineral laws and title to 20 acres of timber as well as the minerals. But national forest managers increasingly saw a need for stronger guidelines and more deliberate efforts to protect the public's interest in proper land and resource management on frivolous claims.

In the early 1950's, the Forest Service proposed the separation of surface and subsurface (mineral) rights as one solution to the growing problem of managing surface resources on claims and adjacent lands. This did not jeopardize the interests of legitimate miners, but it could prevent abuse of mining laws from spurious claims and interference with managing other national forest uses and resources. The American Mining Congress, representing the mining industry, agreed that it was time to face the problem, and a new law, the Mining Claim Rights Restoration Act, was passed in 1955. It separated surface rights from subsurface rights while permitting legitimate mineral exploration and mine operations. The law also withdrew the staking of mining claims to extract common-variety materials: sand, stone, gravel, common pumice, and cinders. These became "salable" minerals subject to permits and sale under direct national forest supervision.

Uses unrelated to mining were no longer permitted on mining claims, nor could claimants remove timber except as needed to operate their claims. In addition, the 1955 Mining Act provided a procedure requiring the claimant, upon proper notice, to prove his or her claim was valid. The national forests promptly instituted a review process, guidelines, and a schedule to identify valid claims — a review that took 12 years to complete. Some 1.2 million claims were identified, covering 24 million acres. Tens of thousands of dormant and abandoned claims were eliminated. By 1967, national forest managers had validated 13,371 claims, less than 2 percent, on the basis of verified claimant statements.

National forest managers reviewed hundreds of occupancy applications on unpatented claims where claimants had become occupant-owner residents of valuable improvements. Qualified claim occupants — those entitled to surface rights — received relief through leases, special use permits, or purchase of the occupied site or an alternate site, but this type of relief required that all rights to the unpatented mining claim be reverted to the Government. Thus, the age of frivolous national forest mineral claims eventually came to an end (USDA Forest Service 1956-1968).

During the 1950's and 1960's, except for periodic spurts of uranium prospecting and a few high-value minerals, most national forests were not very active in hardrock mineral or energy development. The principal, and largely sufficient, sources of domestic ores and energy were being located on private and BLM lands. The more remote, topographically rough, and difficult to access national forests were largely ignored — with the notable exceptions of nickel, cobalt, and uranium (Peterson 1983).

During the cold war and missile-driven uranium boom, claimants filed about 5,000 claims per month. In the late 1960's, renewed interest in prospecting for uranium, silver, copper, molybdenum, and gold again prompted the staking of many hundreds of claims on national forests. The number of claims examined for compliance with mining laws rose to 4,000 per year, and surface rights were coordinated on 10,000 to 40,000 claims each year.

During the 1960's, as public interest in protecting natural resource conditions grew and the environmental cause emerged, some mining companies began to introduce resource protection measures into their national forest operations. For example, national forest managers and six major mining companies cooperated to ensure environmental protection in developing their leases on Missouri's Clark National Forest. By the terms of their leases, permits, and agreements, these companies took action to control erosion, prevent stream pollution, revegetate disturbed lands, and reduce harmful air emissions. In Colorado, the American Metal Claim Company (AMAX) cooperated with national forest managers; the Colorado Game, Fish, and Parks Department; and the Colorado Open Space Foundation to plan and operate mining projects near a well-known ski resort on the Arapaho National Forest. Environmental protection practices focused on maintaining water quality for established uses; providing both winter and summer recreational opportunities, including swimming, hiking, hunting, and camping; and creating a pleasing appearance (USDA Forest Service 1970). These actions were at the forefront of the mining industry's response to intensifying concerns about national forest environments.

But there also were more challenging situations. In 1969, the American Smelting and Refining Company (ASARCO) located a major molybdenum deposit in the highly scenic and game-rich White Cloud Peaks area on Idaho's Challis and Sawtooth National Forests. ASARCO applied for a special use permit to build an 8-mile access road to its claim. It worked closely with national forest managers to evaluate road access options for minimizing impacts on the area's sensitive scenery, ecology, and game resources. Nonetheless, ASARCO's proposed development became very controversial. Conservation interests opposed the road proposal and argued that the permit be denied due to threats to wildlife, water quality, and scenic values. They felt that protection of these resources outweighed the benefits from mining a relatively abundant mineral (Wilkinson and Anderson 1985).

In the public press, writers protested the rationale that gave mining top priority on a pristine 80-square-mile national forest area that included 54 scenic mountain lakes and one of Idaho's few glaciers. They urged that the White Cloud area be closed to mining. Under the mining laws, national forests had no regulations to control prospecting or to protect surface areas, water quality, fish, wildlife, timber, or soil resources; they also lacked authority to deny access. Their authority was limited to regulating the manner and route by which a road could be constructed. National forest managers held three public meetings on the White Cloud issue, which then became moot in 1970 when ASARCO, due to political sensitivity and a weak molybdenum market, withdrew its permit request and ceased further development (Wilkinson and Anderson 1985). In 1972, Congress added the White Cloud area to the Sawtooth National Recreation Area, where mining was permitted only under strict resource protection standards: the use of tracked vehicles and other moving equipment on this highly scenic area with fragile soils and frail ecology susceptible to aesthetic damage was prohibited or restricted. The White Cloud issue illustrated how national forest authority was limited to managing only surface resources on claims filed under U.S. mining laws. It also illustrated the influence of environmental interests.

|

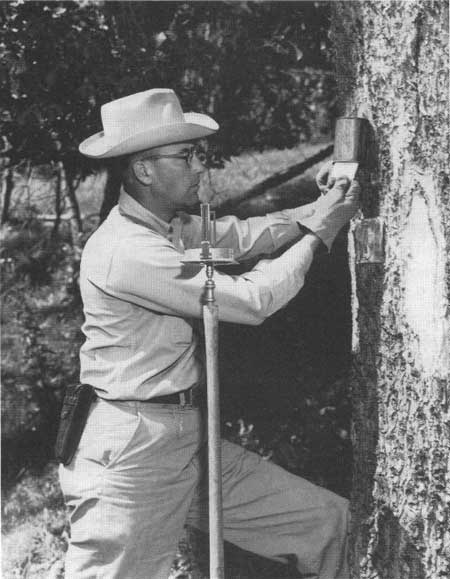

| Forester measuring a 46-inch d.b.h. western white pine on a timber-survey sample-tree measurement plot, Powell Ranger District, Clearwater National Forest, Idaho, 1951. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by L.J. Prater.) |

Using and Managing Timber Resources

The military's demand for timber products abated abruptly after 1945, but rising domestic housing demands quickly absorbed wartime timber supplies and more. Annual housing starts rose to 1.5 million per year by 1950 and remained at that average level until 1970. National forest timber supplies increased from 3.1 bbf in 1945 to 3.5 bbf in 1950. Between 1945 and 1950, even though demand for wood was strong and rising, expansion of the national forest timber harvest was dampened by the lack of adequate roads. Road construction budgets were scarcely enough to maintain wartime harvest levels. In 1946, the Federal Housing Expediter eased this situation by allocating funds "to build 1,443 miles of access roads, and reconstruct 656 additional miles to develop a maximum contribution from national forests toward providing more lumber for veteran's housing" (USDA Forest Service 1945-1950).

Congressional leaders, administration officials, and national forest managers saw expanding national forest softwood sawtimber harvests and producing high-quality wood products as performing a social service to the Nation. The softwood timber inventories of the Northeast and Lake States had been heavily depleted by the early 20th century. In the South, supplies of large trees and high-quality timber were declining rapidly and the smaller second-growth trees were producing low-quality wood products. Southern softwood inventories were also declining as timber harvests continued to exceed the growth of younger stands (USDA Forest Service 1945-1950). National forests, at this time, held half of the Nation's softwood timber inventory, primarily in mature and overmature stands in the West (Powell et al. 1992).

In the West, the national forest allowable cut was the calculated timber volume that could be sold and harvested in each year of the current decade and each decade thereafter on a long-term, sustainable basis. This calculation was based on the planned life (rotation age of the managed forest) of the existing old-growth timber inventory and the accretion from the estimated growth of any young timber in these stands and expressed on an annual basis.

During the postwar years, allowable cuts were separate determinations in the national forest timber management plans prepared each decade for some 400 working circles. Working circles basically represented the efficient national forest timber supply areas for the established local timber industry. Working circle allowable cuts were summed up to estimate the allowable cut for the whole forest.

Actual annual timber sale volumes generally lagged behind calculated allowable cuts because some timber markets were limited by industry's milling capacity or the available timber harvest included species for which markets were limited or nonexistent — a common situation in the Rocky Mountains. Lack of staff and funding to prepare timber sales and build access roads contributed to this lag. National forest managers viewed the allowable cut estimates as an upper limit to the average annual and decadal sales level while the western timber industry interpreted them as lower limits for timber sales and expected the full amount of the allowable cut estimate to be offered for sale throughout the 1945 to 1970 period. During the 1940's and 1950's, and into the 1960's, the industry widely held the view that national forest estimates of the full allowable cut were conservative compared to the sustainable harvest potential. They continually pressured national forest managers to raise allowable cut estimates. The allowable cut, or the allowable sale quantity (ASQ) as it came to be called in the 1980's, became a persistent and divisive issue between the timber industry and the Forest Service (Cliff, no date).

In 1950, the allowable cut level for all national forests was 6.0 bbf, but actual timber harvest volume, due to lack of access, was limited to 3.5 bbf. As staffing and funding improved, road construction and reconstruction accelerated from 2,000 miles per year in 1950 to 4,700 miles in 1960. Timber sales and harvests during the 1950's rose almost every year. Timber harvests reached 9.4 bbf in 1960 — 85 percent of the allowable cut of 11.0 bbf (fig. 6). The decadal updating of inventories and management plans with more accurate and detailed data permitted a steady rise in the calculated estimate of the sustainable allowable annual cut for the 400 national forest working circles. Such data included new information on growth, reproduction stocking, protection, reforestation and stand improvement practices, access, wood utilization standards, and inventory levels. Changing technologies and improved timber inventory methods were especially important. They made intensive timber utilization more economical and timber inventories more accurate. These improvements continued to influence yields and harvests through the 1960's as the total national forest allowable cut rose to 12.9 bbf in 1969. In that year, the harvest rose to 11.9 bbf — almost 8.4 bbf more than in 1950 — and to 92 percent of the allowable cut (USDA Forest Service 1945-1970, 1984, 1993).

|

| Figure 6. National forest timber sold and harvested, 1950-1969. Source: USDA Forest Service. |

Ninety percent of the increase in national forest timber harvests came from the western old-growth. The largest share came from Washington and Oregon with 41 percent, northern California with 20 percent, and Idaho and Montana with 15 percent. Small increases in the rest of the Rocky Mountain and Great Plains States forests added 9 percent, Alaska had 5 percent, and the remaining 10 percent came from the eastern and southern national forests (USDA Forest Service 1993).

|

| Clearcutting by staggered settings in old-growth on the Willamette National Forest, Oregon, 1953. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by Thomas C. Adams.) |

In the East, national forests focused on rehabilitating the heavily cutover, often burned-over acquired forests and reforesting abandoned farm croplands and fields. Planted forests were still too young to be harvested for saw-timber. To rebuild growing stocks and sawtimber inventories in the rehabilitating forests, only half of the growth was being harvested. Thus, average annual timber sales and harvests of the southern and eastern forests were limited to about half of their sustainable allowable cut levels.

During the late 1940's and 1950's, national forest timber supplies in the Douglas-fir areas of western Oregon and Washington offset the timber harvest decline on private lands. As a result, the total harvest in western Oregon and Washington during the 1950's remained relatively stable at an average annual level of 10.9 bbf, while the harvest share from Federal lands rose from 25 to 37 percent. Some lumber mills, however, went out of business for lack of logs, as the larger and higher quality logs were increasingly used for plywood by an expanding softwood plywood industry. Many lumber mills short of timber supplies shifted their operations to northern California, Idaho or Montana, and Canada, where available public timber supplies helped expand jobs and community growth (Fedkiw 1964; USDA Forest Service 1993).

Nationally, the rising western national forest harvest offset large declines in softwood sawtimber harvests and lumber production in the younger, much cutover, and declining private inventories in the East and South. Softwood lumber production in the South had dropped from 10 bbf in 1940 to less than 6 bbf in the early 1960's and 7 bbf in 1970. In the New England, Mid-Atlantic, and Lake States, softwood lumber production declined by 1 bbf in the same period. The huge old-growth reserves of the western national forests provided 20 years of reduced market pressure on the declining softwood sawtimber stocks on industrial and other private forest lands in the East and South. This respite in sawtimber harvests in the eastern United States helped to increase the rate of regrowth and buildup of softwood timber stocks, particularly in the Southeast and Northeast, which became important sources of increased sawtimber supplies during the 1970's (Ulrich 1989; Wheeler 1969; Row 1962).

Sustained-Yield Units and Long-term Timber Supply Contracts

Up through the 1940's, national forest managers used sustained-yield units and long-term timber supply contracts to advance community development and stability and to develop young, managed forests. The Sustained Yield Forest Management Act of 1944, passed largely through the efforts of the Western Forestry and Conservation Association and with the support of timber companies in need of new log supply sources, authorized the Secretary of Agriculture to establish cooperative and Federal sustained-yield units on national forests. The Act was designed to promote forest industry, employment, and community stability where sustained-yield units could ensure a stable and continuous timber supply. By 1945, national forests in seven regions had identified 64 potential opportunities for cooperative sustained-yield units and more than 61 opportunities for Federal sustained-yield units, and had applications for 60 cooperative units and 16 Federal units (Clary 1986).

Sustained-yield units could be established on national forests where community stability depended on Federal forest timber supplies and where such supplies could not be assured through the usual timber sale bidding procedure. The sustained-yield unit was designed to supply the timber needs of such communities on a sustainable basis without competitive bidding, but at prices not less than the appraised value of the timber. A cooperative unit was an agreement between an industrial or other private timber landowner and the national forest to establish and manage a unit made up of both private and national forest timberlands. A Federal unit contained only national forest timberlands.

Only one cooperative unit was ever established — the Shelton Cooperative Sustained-Yield Unit on the State of Washington's Olympic National Forest, established in 1947 through a 100-year agreement with the Simpson Logging Company. The unit included 110,000 acres of virgin national forest old-growth and 159,000 acres of Simpson's second-growth and regenerating forests. This cooperative arrangement provided the Simpson Company a sustainable timber supply of 90 million board feet per year. Without this cooperative arrangement, the Simpson harvest would have been 50 percent lower, mills would have closed, and 1,400 people in the local communities of Shelton and McCleary would have lost jobs (Clary 1986; Steen 1976). The Simpson unit was effectively phased out in the 1980's, as its dependence on national forest timber declined to zero. Simpson's timber needs are now being supplied by the regrowth on company lands, but the formal contractual dependency on national forest timber remains a valid agreement.

Just five Federal sustained-yield units were ever established. They reserved a total 1.7 million acres of national forest timber lands in Arizona, California, New Mexico, Oregon, and Washington. These units essentially guaranteed a sustained timber supply to local mills located in small communities dependent on the timber industry. Each, however, became a continual source of complaints and frustration to national forest managers (Clary 1986). All units are still in existence, except the one in Flagstaff, Arizona, which was developed in 1948 to support two sawmills. In 1980, the Coconino National Forest shut this unit down when the surviving mill had grown strong enough economically to operate without the preferential supply of a sustained-yield unit (Clary 1986).

In the face of strong opposition from many segments of the timber industry, conservation groups, organized labor, civic organizations, and communities, national forest efforts to advance community stability through sustained-yield units faded in the 1950's. One of the outgrowths of the retrenchment was the development of oral timber sale bidding in the Pacific Northwest. Oral bids gave local timber firms an opportunity to meet "outside" competition and thus support community stability (Leonard 1995).

National forests offered long-term timber sale contracts to encourage the development of the pulp and paper industry. In 1950, a public auction of 4.5 million cords of pulpwood on four Colorado forests culminated years of effort to develop a market for the Engelmann spruce timber that dominated the mountain slopes of the upper Colorado. The sale required erection of a pulp mill with a capacity of 200 to 250 tons daily and would keep that mill supplied for 30 years. Since two-thirds of the sale area timber was dead — killed by tiny spruce beetles — the sale also became a gigantic salvage project. In the high mountains, short summers and low humidity kept the beetle-killed timber in usable condition for pulpwood for many years.

|

| Winberry sale unit, Willamette National Forest, Oregon, clearcut in 1951, showing advanced regeneration and brush in 1957 after 1953 replanting. Brush provides wildlife habitat and forage until shaded out by new tree crop. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by L.J. Prater) |

In 1958, Alaska's Tongass National Forest awarded a long-term pulpwood sale of 1.5 billion cubic feet to the Ketchikan Pulp and Paper Company. This culminated three decades of effort to bring a pulp and paper industry to southeast Alaska. The sale required construction of a 300-ton capacity mill that would employ 800 people, and would supply that mill with 50 years of pulpwood. There were three additional long-term sale contracts; two have been canceled (the latest, Alaska Pulp Corporation in 1993), and a third, the Pacific Northern Sale, was modified to a 25-year contract when pulp mill construction became infeasible. The 25-year contract was completed in the 1980's by the Alaska Lumber and Pulp Company (now Alaska Pulp Corporation) (Leonard 1995). Only one long-term contract, Ketchikan Pulp's, remains operational — but under revised terms and reduced volume. These were among the last long-term timber sale contracts that national forests granted.

Timber Management Planning

Until the late 1970's, there were very few and only rudimentary national guidelines for overall national forest management planning. Official regulations, focused primarily on timber management, had only six specific requirements. They were to aid in providing a continuous supply of national forest timber; be based on the principle of sustained yield; provide an even flow of timber to help stabilize communities and local employment; help coordinate timber production and harvesting with other national forest lands and uses in accordance with principles for managing multiple uses; establish the allowable harvest rate at "the maximum amount of timber that may be cut from the national forest lands within the unit by years or other periods"; and be reviewed and approved by the Chief of the Forest Service (Wilkinson and Anderson 1985).

Central control and consistency for all timber management plans among the national forests was ensured by the Washington Office review and approval process (Leonard 1995). From Pinchot times, three basic procedural steps have been used in timber management planning: determining the land that was suitable for harvest (the commercial forest land); calculating the amount of timber that could be sold from the suitable land base on a sustained basis; and deciding the appropriate methods for harvesting and regenerating that timber (Wilkinson and Anderson 1985).

Commercial forest land (CFL) included all areas capable of growing at least 20 cubic feet of commercial wood per acre per year in soil conditions, terrain, and locations where logging would not be too costly. CFL excluded lands withdrawn for wilderness, administrative sites, or other purposes. In 1952, CFL made up 94.7 million acres — more than half of the National Forest System. By 1962, there were 96.8 million acres. CFL acres declined thereafter as new wilderness areas were designated by Congress.

|

| Winberry sale unit, Willamette National Forest, Oregon, in 1972, showing 20-year regrowth of Douglas-fir planting following clearcut in 1951. Planted trees are more than 20 feet tall and brush is suppressed. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library.) |

National timber management guidelines gave national forest managers a great deal of flexibility and discretion and placed responsibility for planning and carrying out plans at the national forest and ranger district levels. Some latitude in national direction was desirable and necessary to enable district rangers to deal more effectively with local forest timber type variations and conditions and other national forest resources and uses (Wilkinson and Anderson 1985). The pressure to harvest timber in areas reserved for recreation, landscape aesthetics and watersheds led to more specific guidelines. For example, in rejecting a 1962 plan for "near natural" management in certain zones of California's Sequoia National Forest, the Chief of the Forest Service called for a certain amount of harvesting in some scenic areas. He felt that maintaining all parts of every scenic area in a near-natural condition — in this case, the establishment of virtually unmanaged areas of up to 100,000 acres — was impracticable (Clary 1986). The Forest Service issued new national direction that required allowable cut levels for landscape management areas to be determined separately and used only where there was assurance that the forest and industry could protect the desired features and attractions of landscape areas.

In the mid-1950's, during the planning for the Quilcene watershed on Washington's Olympic National Forest, the city of Port Townsend was concerned about timber harvesting and management in its municipal water supply source. National forest managers assured the city that the Forest would "propose nothing in the way of management that would adversely affect the amount and purity of the water supply." The watershed was part of the Quilcene working circle, and more than half of the watershed supported mature and merchantable timber. The Forest wanted to begin harvesting as soon as possible so that average annual harvest would be smaller (it would be spread out over a greater number of years). The harvest plan stipulated that the timber harvest would be limited to the watershed's sustainable yield of 9.5 million board feet per year; clearcuts would be limited to 30 acres or less (compared to a maximum of 80 acres); each clearcut patch would be reforested soon after slash disposal; and national forest managers would carefully select logging practices to protect watershed conditions (Clary 1986).

1961 National Development Program for National Forests

In 1961, President Kennedy, on behalf of the Forest Service, transmitted a long-term "Development Program for National Forests" to Congress, in which it was determined that the long-term sustainable harvest of national forests under intensive management would be 21.1 bbf by the year 2000. This included an intermediate goal of 13 bbf by 1972 (USDA Forest Service 1961a; Clary 1986). The goals, however, were never realized. Timber sales and harvests averaged less than 12 bbf through the 1960's, 1970's, and 1980's.

|

| Reforestation and clearcutting. A 15-year-old Douglas-fir plantation well-established following a 1950 clearcut, Gifford Pinchot National Forest, Washington, 1955. In the background, a more recent clearcut area with mature timber on either side. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by P. Freeman Heim.) |

Nevertheless, national forests were seen to play an important role in the Nation's timber supply and economy, particularly in the housing sector. The harvesting of old-growth timber, which was often decadent or deteriorating, was also viewed as a positive factor. Such harvests replaced mature and overmature western coniferous forests that had little or no net growth with fast-growing young timber stands (Clary 1986; USDA Forest Service 1945-1970).

Preparation of Timber Management Plans

Forest supervisors and their timber staffs, working with district rangers, prepared timber management plans, although in the major timber-producing regions a significant amount of technical work was centralized in the regional offices — from the taking of timber inventories to the calculation of allowable annual cuts. The Washington Office Timber Staff reviewed timber management plans throughout the 1945 to 1970 period. Often, allowable cuts were increased above pre-war levels to reflect updated inventory and regeneration data, improved harvest methods and equipment, shorter rotations, and higher utilization standards. National forest timber management plans "that did not calculate timber so as to permit the greatest annual allowable cut were returned to the regions for revision" (Clary 1986). The final approval for national forest timber management plans rested with the Chief of the Forest Service.

The Role of Road Development in Timber Resource Management

Developing and maintaining the national forest road system was a primary priority throughout the post-World War II period. Although road access to all parts of the National Forest System was needed to administer, protect, use, and manage the national forests efficiently, timber management to develop vigorous young forests and achieve the full allowable cut became a strong focus for the rapid development of the road system. Timber harvests became the principal basis for financing, justifying, and accelerating the construction of almost all local logging and collector roads, and many mainline access roads. Road system development also allowed the use and management of national forests for other purposes, especially outdoor recreation, wildlife, and fisheries.

An average of 22,000 timber sales per year took place during the 1950's; in the 1960's, the average was 24,000. More than 90 percent were very small sales to small local timber operators and other users, generally less than 100,000 board feet and under $1,000 or $2,000 per sale. About 1,000 sales per year involved 100,000 to 1 million board feet to somewhat larger operators. The bulk of the annual timber sale volume, however, was sold through another 1,000 or so sales of 1 million to 20 million board feet or more to medium- and large-size timber operators. These large sales were an important tool in developing the access road system; they required three types of roads: arterial (mainline) roads, the primary road system to major drainages or large land areas; collector (lateral) roads, to feed into the primary roads and reach smaller drainages and blocks of land; and local roads (logging spurs), temporary, lower standard roads to reach specific timber sales.

|

| Residual ponderosa and sugar pines left as seed source after logging, Umpqua National Forest, Oregon, 1953. Residual trees will be harvested later, after the unit has been restocked. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by E.L. Hayes) |

To extend the road system into previously undeveloped areas, timber sales scheduled many widely spaced timber harvest units. This approach encouraged smaller units that could be harvested and naturally seeded by surrounding timber, artificially seeded, or planted. Such units, with "no cut" areas between, limited the logging disturbance to a relatively small portion of the total timber sale area. The selection harvest system, often used for ponderosa pine, removed only a few trees per acre. Such sales covered larger harvest areas and likewise extended the road system to previously unroaded areas.

Although the national forest road system was initially developed to reach and extract national forest timber, it was seen as the key to opening up the national forests for hunters, anglers, hikers, other recreation interests, and other users. The total permanent road system in 1945 was about 100,000 miles. By 1970, it was nearly 200,000 miles.

Arterial and collector roads were engineered to Government standards and constructed by the Forest Service or the timber operator as a timber sale requirement. Temporary spurs were built by timber operators and treated as logging costs. However, many of these spurs were built on lines staked by national forest engineers where future permanent roads would be needed. Maintenance or reconstruction in later years would add these roads to the permanent road system. Between 1950 and 1970, timber operators built 70 to 90 percent of the annual road miles constructed or reconstructed. The annual mileage built by timber operators rose from 1,500 miles in the early 1950's to 3,800 miles in 1960 and over 6,000 miles by 1970. Roads built by the Forest Service increased from 500 miles in 1950 to 850 in 1960 and 1,100 miles by 1970.

Access To Respond to Natural Disasters

Between 1949 and 1951, repeated hurricane-force storms blew down timber over wide areas of western Oregon, northern Idaho, and western Montana — as much as 8 bbf in Oregon and a half-billion more in Idaho and Montana. National forest managers reoriented timber sales and road plans as soon as possible to salvage the heaviest concentrations of dead and damaged trees.

|

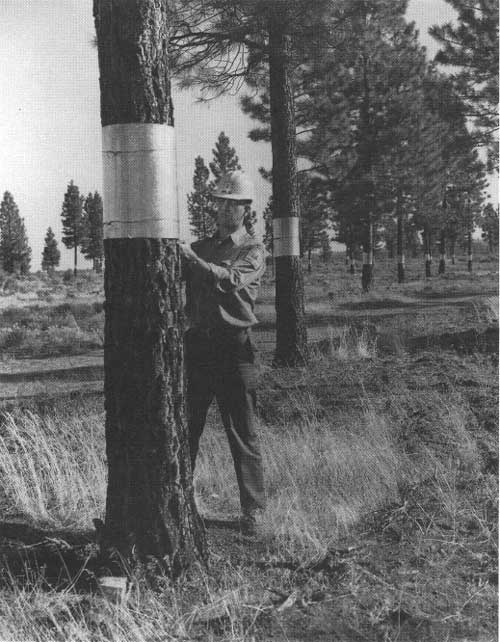

| Ponderosa pine seed orchards, Hackamore area, Modoc National Forest, California. Forest worker installing metal bands to prevent chipmunks from climbing trees to harvest pine cones and eat the seeds. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by John Wicker.) |

With major outbreaks of Engelmann spruce and Douglas-fir beetles in Idaho, Montana, and Oregon in 1952, the emergency efforts shifted to harvest the newly infested timber as soon as possible. A decade later, in 1962, the Columbus Day storm again caused similar widespread timber damage in Washington and Oregon. Redirected timber sales and road construction enabled salvage of 1.4 bbf of national forest blowdown timber by 1964 (USDA Forest Service 1949, 1953, 1964-1965).

Reforestation and Stand Improvement

Before World War II, 1.2 million acres of deforested land had been planted or seeded, and an unknown amount had received timber-stand improvement cuts, weeding, thinning, or pruning. During World War II, these activities were largely suspended. By 1946, some 3.2 million acres of CFL needed reforestation and 3.8 million acres needed some type of timber-stand improvement.

Such work was reactivated in 1946, but it was limited to sale areas where timber operators paid for reforestation and post-harvest stand treatments. In that year, 27,600 acres were planted or seeded. Reforestation had doubled to 56,000 acres by 1955, accelerated to 200,000 acres in 1962, and stabilized at about 260,000 acres per year in the late 1960's. This trend reflected the rising national forest timber harvest level, primarily clearcutting, and a shift away from natural regeneration to planned reforestation. About 50,000 acres per year were being naturally regenerated in the 1960's. Success was improved by brush removal and scarifying the soil surface to expose mineral soil.

National forest tree nurseries were reactivated after the war. In 1950, 13 nurseries produced 45 million seedlings. This rose to 88 million in 1955 and 137 million in 1960, then stabilized at 100 million to 120 million seedlings per year. Superior seed production areas, seed orchards, and hybrid production were developed in the late 1950's. By 1963, national forests had 13 superior forest tree seed production areas on 10,069 acres, and 28 forest tree seed orchards were under development on 1,763 acres. The number of seed orchards and their area continued to expand seed production during the balance of the postwar period.

The quality of regeneration management improved throughout this period. In 1962, the Forest Service established the position of certified silviculturist on national forests and upgraded it to the level of senior timber sale positions. Forest Service research completed studies that improved regeneration methods, seed orchards, seed production, seed and tree quality, and nursery management and production.

Weeding, precommercial thinning, and sanitation cuts to remove both excess and poor-quality trees increased from about 250,000 acres per year in the early 1950's to more than 500,000 acres per year between 1955 and 1963. As thinning costs rose significantly, these activities declined to 300,000 acres in 1970. Other activities were animal damage control, mainly fencing to exclude deer, on about 200,000 acres per year, and rodent control on several hundred thousand acres. Prescribed burns were increasingly used, especially in the South, to protect longleaf pine from brown-spot disease, to reduce understory brush competition, and to prepare the ground for natural seeding (USDA Forest Service 1946-1970).

|

| Foresters on Pisgah National Forest, North Carolina, discussing multiple-use plan for the Pisgah Ranger District, 1963. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by B.W. Muir.) |

Planning for Multiple Uses Under the MUSY Act

The initial planning for managing multiple uses under the MUSY Act established a two-stage process for classifying national forests into land-use zones. Such zones were defined in the first-stage regional multiple-use planning guides. They gave broad direction for establishing, planning, and managing zones for recreation, travel influence, water influence, landscape, grassland, general forest, and formally dedicated areas such as research natural areas and wilderness. The zones varied somewhat among the regions. The general forest zone was usually CFL. Wildlife areas were not zoned because wildlife occupied all zones. All regions required the water influence, travel influence, and dedicated-area zones. Regional guides, however, did not give any direction on the use combination or pattern of uses that would best meet the public's needs within the regions nor how the use combinations or patterns should be determined. Multiple uses actually were coordinated incrementally on the ground through management decisions and practices within each land-use zone as the demand for uses emerged, site by site and year by year (Wilson 1967, 1978).

In the second stage, district rangers prepared district multiple-use plans that classified their entire district into land-use zones. These plans were used to decide where management activities should take place. District plans did not withdraw CFL from timber production; rather, they directed the protection of landscapes, water quality, recreation, and other resources within the land-use zones. Timber planners were required to ensure that timber harvest plans would protect other designated zone values. Sometimes this direction required reducing the allowable cut or modifying management practices. Resource planning for nontimber uses created other difficulties. For example, wildlife resource planners would often categorize CFL within a general forest zone as elk winter range, which called for adaptation of timber harvests and management. Thus, wildlife management under the multiple-use plans was essentially a matter of coordination with other uses rather than a matter of separate zoning. In time, it became apparent that neither the functional resource plans of the earlier years nor the multiple-use plans of the 1960's provided any clear or uniform guidelines for coordinating multiple uses (Wilkinson and Anderson 1985; Wilson 1967).

Insect and Disease Management