|

Managing Multiple Uses on National Forests, 1905-1995 A 90-year Learning Experience and It Isn't Finished Yet |

|

Chapter 4

Policy Issues and Management Conflicts Challenge Multiple-Use Planning and Management During the 1970's

The National Setting

National demands for timber, energy, water and water quality, beef, wildlife and fish, and opportunities for outdoor recreation and wilderness experience continued to increase dramatically during the 1970's. National awareness of environmental systems — their composition, structure, and functions — and the public interest in the need to sustain them for the needs of future generations likewise increased as the environmental movement continued to advance. These burgeoning demands and the growing public awareness of environmental concerns intensified pressures on all the uses of national forest lands and resources as well as the calls for preservation and management adjustments to keep their environmental systems healthy, diverse, and productive.

In this setting, conflicts over the use and management of national forests opened up national policy issues and debates that burdened and challenged the Forest Service throughout the 1970's. At the field level, national forest managers struggled to respond to the rising demands for use and, as well as they could, to the national policy issues and growing management challenges. This chapter addresses the major policy issues and debates of the 1970's. Chapter 5 reviews the actual performance of national forest land and resource management at the field level.

Huge increases in lumber and plywood prices beginning in the late 1960's and continuing throughout the 1970's raised the concern and efforts of the Administration and Congress to expand timber supplies from national forests. Controlling this inflation became a priority because lumber and plywood prices were adding disproportionately to the national inflation problem. In 1968, President Johnson proposed the construction of an additional 26 million housing units in the next decade — fully a million more units per year, than those built annually between 1950 and 1968. The housing goals not only called for a decent home for every family; the low-income housing target became an important component of the Administration's national poverty program. Such goals, in turn, were seen as a growth opportunity for both the housing and timber industries. Rising lumber and plywood prices increased housing costs and were seen as a threat to achieving these goals.

The controversy over clearcutting on national forests was elevated to a national policy issue. In order to raise and maintain the allowable cut, the timber industry sought legislation to increase funding to manage national forest timber resources more intensively. Wilderness interests and environmentalists opposed national forest timber harvest increases and turned to litigation under NEPA and related legislation to achieve their national forest management and wilderness designation goals.

The Forest Service, in an effort to overcome a growing uncertainty about the management of de facto wilderness areas, particularly as it related to timber harvest planning, initiated the Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE) process to speed up the designation of wilderness areas and release nondesignated roadless areas for multiple-use management. A court challenge aborted the RARE process. Wilderness planning was slowed to a snail's pace. Roadless areas could not be entered without NEPA-based environmental analysis. As a result, timber harvesting was increasingly concentrated on already roaded timber lands. This contributed fuel to the issues of clearcutting and the general adequacy of national forest management.

Wilderness, environmental, and conservation interest groups became polarized against commodity producers over the proper use and management of the national forests. The issue was exacerbated by acknowledged shortfalls in the implementation of clearcutting on some national forests. The Forest Service estimated that the 1970 national forest allowable cut, 12.9 bbf, could, with more intensive management, be increased by 7 bbf by 1978. It also firmly believed that the increase could be realized with greater funding and guarantees that those increases would remain available in future years. As NEPA's environmental quality implications became clear, the potential allowable cut was further qualified as the most timber that could be made available without unacceptable environmental impacts.

The year 1970 introduced a decade of new direction and guidelines for managing multiple uses on national forests; it became a decade of adaptation by national forest managers. Court suits over national forest planning and management multiplied. Congressional efforts at substantive legislation to resolve the polarization between commodity and amenity values failed. However, consensus emerged on procedural legislation and guidelines for long-term national planning for the National Forest System, research, and State and private forestry programs — the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act of 1974 (RPA) — and for the planning and management of the individual national forests — the National Forest Management Act of 1976 (NFMA).

This chapter reviews the management conflicts over and the emergence of new national policy for the use and management of national forests and how that policy changed procedures and guidelines for planning and managing multiple uses. It also reviews the performance of the Forest Service's hierarchical organization and decentralized management in addressing these issues.

Administration and Congressional Efforts To Expand

National Forest Timber Supplies

Housing Goals, Timber Demands, and Price Responses

The enactment of the Housing and Urban Development Act of 1968 increased the concerns of Congress and the Administration about expanding timber supplies from national forests and other sources. It reaffirmed the Housing Act of 1949's goal — "The realization as soon as feasible of the goal of a decent home and a suitable living environment for every American family." Congress determined that the Johnson Administration's goal of 26 million housing units could be substantially achieved. The 1968 housing legislation directed the President to present a 10-year detailed plan and schedule to achieve his goal and to report on its progress annually. If performance failed to meet scheduled targets, the President's report was to explain why housing targets could not be met and what steps needed to be taken to achieve rescheduled targets in subsequent years.

This legislation was extraordinary in two ways. It established national housing goals in quantitative terms for a fixed time period — an unprecedented approach in national policy. It also required monitoring public and private performance in meeting scheduled annual targets and revision of plans and targets in the event of a shortfall.

Increasing the Nation's housing inventory by 26 million units was an ambitious initiative; it responded to the need to replace aging housing and meet housing needs of the maturing postwar Baby Boomers. At spring 1968 congressional hearings, officials of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) testified on the feasibility and economic effects of the Administration's proposed housing goal. They felt that there was no reason that industries supplying major building materials, such as lumber and plywood, could not supply the additional requirements to meet the President's goal.

USDA also participated in the development of the President's housing proposal. After the proposal was sent to Congress, the Secretary of Agriculture's planning, evaluation, and programming staff evaluated the timber supply and demand impacts of the proposed increased housing construction. It determined that the increase would double 1965-67 timber prices and increase lumber and plywood prices by about 6 percent per year (USDA 1968). It reported that increases in softwood timber harvest from Federal lands were the most effective way for the Federal Government to increase timber supplies and dampen lumber and plywood price inflation, and that rapid increases in Federal timber harvests would raise issues with public groups interested in natural beauty and wilderness objectives.

The Secretary of Agriculture transmitted the special study findings and his timber program recommendations for the President's fiscal year 1970 budget to the President's Office of Management and Budget (OMB) in September 1968. The recommendations proposed modest increases in national forest timber sales, reforestation, and timber stand improvement and restoration of the forest road construction program that had been sharply reduced in FY 1969 as an anti-inflation measure; increased funding for recreation, with smaller increases in other nontimber resource areas; small increases in all Forest Service research program areas; and technical assistance to encourage greater timber harvesting on nonindustrial private lands. The President's FY 1970 budget retained the pattern of proposed increases, but reduced their amount due to other national priorities and tight budget ceilings designed to contain general inflation.

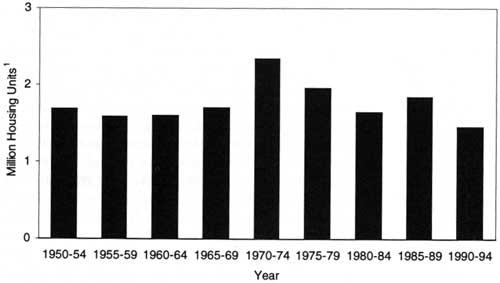

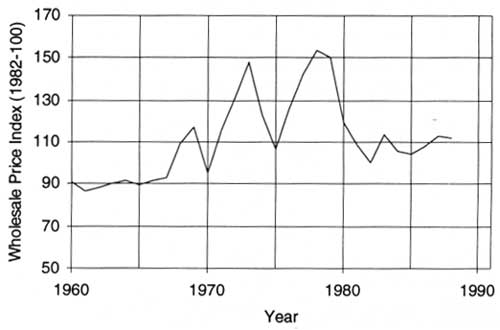

In the meantime, housing construction rose steadily from an annual rate of 1.4 million units in January 1968 to 1.7 million units in the first quarter of 1969 (fig. 10). During the same period, the relative price of softwood lumber rose similarly, but more rapidly (fig. 11). By March 1969, it was 50 percent higher than the average, largely stable lumber price level between 1950 and 1968. But U.S. lumber production did not rise — it stayed at the average annual level of the previous 17 years, 29 bbf.

|

| Figure 10. Average new housing units constructed annually per 5-year period, 1950-1994 (includes new housing starts and mobile home shipments). Source: USDA Forest Service; U.S. Bureau of the Census. |

|

| Figure 11. Wholesale price trend for softwood lumber, 1960-1988. Index = average current market price of all softwood wood lumber divided by the producer price index for all communities. Source: USDA Forest Service 1990. |

Softwood plywood relative prices were at their historically lowest level in 1967. They had declined steadily since 1950, by 45 percent, while plywood production had risen each year to almost 5 times the 1950 production — largely as a result of plywood substitution for the softwood lumber boards traditionally used for sheathing, subflooring, and roof enclosure in housing construction. The plywood itself was more costly, but it cost less to install. By March 1969, plywood relative prices had risen to 100 percent above 1967 levels, but plywood production had risen only 15 percent.

The timber industry quickly interpreted these sharp rises in lumber and plywood prices without corresponding rises in lumber and plywood production as a critical short-term softwood sawtimber shortage. Price increases on national forest timber were much greater, and, in part, reflected some speculative bidding in the timber industry. Timber and housing industry officials quickly informed the Administration and Congress of the timber supply shortage, rising timber prices, increasing lumber and plywood costs, and the increasing cost of housing construction (American Enterprise Institute 1974; Le Master 1984).

The Administration's Initial Response to Rising Timber Demands and Prices

National elections brought a new Republican Administration in January 1969, with a new set of policy officials. By early March 1969, the new Director of the Budget, responding to USDA's special study and the lumber and plywood price market signals, and to evaluate possible policy and program changes for FY 1971 and subsequent budgets, requested the USDA to prepare a careful analysis of timber supply alternatives and their budgetary and social implications. At the same time, the new Cabinet Committee on Economic Policy appointed the Interagency Task Force on Softwood Lumber and Plywood under the Budget Director to study the price, demand, and supply situation and recommend appropriate short-term actions to ameliorate the price pressures.

The task force analysis for the short term was quickly completed and its recommendations approved by the President — all within 2 weeks. It called for easing short-term transportation bottlenecks in lumber and plywood shipments; increasing FY 1969 Federal timber sales by a billion board feet, mainly from national forests, but also 10 percent from BLM lands; closely supervising defense wood products procurement; and negotiating with Japan to reduce log exports from the West Coast.

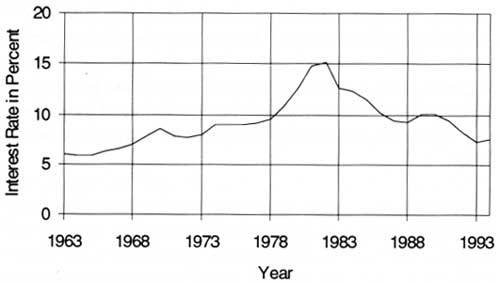

In the early spring of 1969, due to mortgage credit shortages and rapidly escalating interest rates (fig. 12), there was a sudden, unexpected decline in housing construction, which caused lumber and plywood prices to fall sharply. The lumber and plywood shortage and price problem promptly dissipated for the rest of 1969 and remained dormant through the 1970 general economic recession and reduced housing construction. The task force, nevertheless, believed that timber supplies and prices would be a continuing problem for national housing goals and directed the Forest Service and the BLM to analyze possible timber sale increases on their lands — giving equal weight to ensuring environmental quality.

|

| Figure 12. Trend of new home mortgage interest rates, 1963-1994. Source: Economic Report of the President 1995. |

The planned FY 1969 public timber sale increases were not realized. Actually, national forest saw timber sold in FY 1970 dropped 1.2 bbf below the 1968 sales level of 10.8 bbf — a decrease caused by the extremely high appraised prices generated for national forest timber by the rising housing construction and lumber and plywood prices in 1968 and early 1969 and the low timber demand following the sudden drop in housing construction and lumber and plywood prices in the balance of 1969 and 1970. The timber industry appealed the situation to the Secretary of Agriculture, and almost all of the planned but unsold FY 1969 national forest timber sale offerings were reoffered in FY 1970. To reduce any future lags between national forest timber sale price appraisals and a rapid decline in lumber and plywood prices, the Forest Service adjusted its method of updating appraisal prices to reflect the current timber market. With these adjustments, timber sold on national forests rose to 12.3 bbf in 1970. The planned sale volume for FY 1970 was 12.7 bbf (USDA 1972).

Congressional Response and the Timber Supply Act of 1969

In the spring of 1969, both houses of the 91st Congress held hearings on lumber price increases, rising housing costs, and the problems of lumber production. They focused on the adequacy of the President's proposed actions, the need for additional forest roads, and the long-term alternatives for expanding timber supplies. The more than 40 witnesses included representatives from HUD, the housing industry, and a cross-section of timber product manufacturers as well as "government and private witnesses," all of whom Senator John Sparkman of Alabama, chairman of the Senate hearing, said "hold the solution to the problem." The latter included representatives of the Forest Service, the BLM, and nonindustrial forest owners and wilderness, recreation, and wildlife advocates.

There was little disagreement about the issue. It was succinctly defined by the question raised by the President of the National Homebuilders Association: How is the housing industry going to get the lumber and plywood to construct an average of 2.6 million units per year to 1978, the goal of the 1968 Housing Act, when the industry can not get enough timber and wood products to produce 1.5 million units in 1969? The Senate hearing concluded that national forest timber harvests, with 50 percent of the Nation's softwood sawtimber inventory, were much below their potential. The Senate's report on the hearings emphasized that national forest timber production could be substantially increased and assure future supplies if "the necessary investment was made in intensive forest management on a continuing basis" (U.S. Senate 1969).

Shortly after the hearings, the timber industry, to substantially increase annual national forest timber production, drafted a legislative proposal to establish a fund from national forest timber receipts to finance silvicultural practices. The proposal reflected the findings of the Forest Service's Douglas-fir supply study on alternatives for increasing timber supplies on national forest lands in the Douglas-fir region of western Washington and Oregon and northern California (USDA Forest Service 1969b). The findings showed that the allowable cut could be substantially increased if guaranteed sustained annual investments could be made for reforestation, timber stand improvement, thinnings, and other practices to increase the intensity of timber management, and for adequate road access to accomplish them. Chief Edward Cliff enunciated this finding. The principal emphasis of the industry's proposal was on increased sustained annual investment (Le Master 1984).

Annual appropriations for forest management were typically viewed as postponable because the return on timber investments was seen as occurring only in the long term. Congress readily justified such postponements using inflation control and other short-term financial budget pressures as a rationale. Nevertheless, the timber industry proposal was favorably received by several members of Congress. It was introduced under the common title of the National Timber Supply Act of 1969 in both the Senate and House in April 1969 and the House Subcommittee on Forests scheduled hearings on the House version (H.R. 10344) for May 1969. There was widespread, bipartisan support for this bill, which was cosponsored by 56 Congressmen.

The hearings on H.R. 10344 drew testimony from 63 witnesses, including representatives of 10 environmental, conservation, and wilderness interest groups. All 10 opposed or called for substantial modification of the bill's strong timber orientation. The timber industry supported the bill vigorously. The Administration generally opposed establishing a permanent trust fund because such funds reduced future budget flexibility. As the hearings drew to a close, however, the USDA proposed minor funding revisions and amendments to ensure funding increases for managing the nontimber multiple uses and resources that would be affected when timber sale levels were increased.

Conservation groups saw H.R. 10344 as a threat to future wilderness designation and the development of recreational and other nontimber national forest resources and a hazard to the best allocation of available funds among national forest uses and services. The executive director of the National Wildlife Federation submitted testimony that made it clear that the Federation would use all its energy and resources to "go to the people" if the timber industry persisted in its efforts to increase Federal timber harvests where it would be "unwise" from the point of view of all land values (Le Master 1984).

The Sierra Club said it supported more intensive management on certain national forest lands, but only under the following conditions: sound, ecological forest principles would be followed rather than the maximum production of timber in the shortest time; strict provisions would be made to ensure protection of all multiple-use values, even where timber was the main objective; intensive management would occur only on lands that everybody plainly agreed should be managed for timber; and areas having outstanding scenic and wilderness values, long identified and stated by conservation groups locally and across the country, would be excluded from H.R. 10344 policy direction.

The environmental, conservation, and wilderness interests thus saw the Timber Supply Act as giving timber dominance over other resources that were to be given equal consideration under the MUSY Act of 1960. Both the Sierra Club and the Wilderness Society saw H.R. 10344 as foreclosing designation of de facto wilderness areas, largely roadless areas that a national forest had defined as capable of growing commercial timber products and providing other multiple uses (Le Master 1984).

Responding to the hearings, the House Forests Subcommittee extensively revised H.R. 10344 to address the objections of conservation, environmental, and wilderness interests while maintaining its key feature: a "high timber yield fund" based on "all the unallocated receipts from the sale of timber and other forest products, to sustain intensive timber management practices on national forests." The revised bill was replaced by a "clean" bill, H.R. 12025. After the Subcommittee and full Committee adopted additional amendments, including a broader title — the National Forest Conservation and Management Act — it was favorably reported by the Subcommittee in September 1969 by a vote of 23 to 1 (Le Master 1984).

Although much of the bill's interest and urgency was lost with the collapse of lumber and plywood prices in the spring of 1969, the timber industry saw it as a victory (AEI 1974). In December 1969, however, the Sierra Club, the Audubon Society, the Izaak Walton League, the National Rifle Association, the Wildlife Management Institute, Trout Unlimited, Friends of the Earth, and the Committee on Natural Resources sent out telegrams and letters warning that H.R. 12025 "threatens America's national forests, scuttles historic multiple-use practices, and undermines prospective parks, wilderness, open space, and recreation areas." They also initiated a grassroots campaign to encourage their members to send letters and telegrams to Congress (Le Master 1984).

Final debate and House action on H.R. 12025 were scheduled for late February 1970. The resolution to debate the measure was defeated by a vote of 225 to 150 with 52 abstentions. Opposition from conservation, environmental, and wilderness interests contributed importantly to this defeat. The bill died without a discussion of its merits on the House floor. Other contributing factors were the return of lumber and plywood prices to 1967 levels, restoration of adequate timber supplies in early 1970, and a first cresting of popularity of the new environmental movement. The expressed opposition of Wayne Aspinall of Colorado, Chairman of the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs and Chairman of the Public Land Law Review Commission (PLLRC) authorized by the House Committee in 1964, was also a critical factor. He agreed with the motives for the introduction and support of H.R. 12025, but considered any action on the legislation at that time to be untimely. He favored a more balanced solution of the timber supply problem based on the PLLRC report, which was to be released shortly and was not yet available to Congress. Aspinall's approach favored classification of national forest lands by dominant uses, including commercial timber production, as opposed to the multiple-use approach. But this idea never made any policy headway. The PLLRC report was largely ignored. Its recommendations were commodity oriented and out of step with environmental concerns and NEPA policy direction (Le Master 1984).

Emergence of the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act in 1974

In 1971 and 1972, housing construction rose to new peaks, 2.6 million and 3.0 million units, respectively, then dipped back to 2.6 million units in 1973. Lumber relative prices rose by 50 percent; plywood prices by 40 percent. They contributed disproportionately — several times their weight in the wholesale price index — to the general inflation that the President's Economic Stabilization Program was trying to control. The program's credibility was being affected by the magnitude of lumber and plywood price increases (Fig. 13) and by reported irregularities and distortions in the industry's response to price-control efforts. At the same time, the Government was seen as a major contributor to both the demand problem (through the housing goals) and the supply problem (through inflexible national forest timber supplies).

|

| Figure 13. Price increases for softwood lumber, 1970-1979. Source: Ulrich 1990. |

In March 1973, more than 2,000 members of the National Association of Homebuilders and the National Lumber and Building Materials Association staged a mass meeting in Washington, D.C. They were strongly supported by the National Forest Products Association. They "marched" on congressional and Federal agency offices to dramatize the seriousness of the lumber and plywood supply problem for homebuilders, who were increasingly unable to get framing materials — a problem that the President of the Homebuilders Association said was intensified by the failure of the national forests to make the full allowable cut available.

Between 1971 and 1973, a period of rising lumber and plywood demands and prices, there were repeated efforts to pass legislation to increase present timber supplies by intensifying the management of national forest timber. In 1971, Congressman Charles Griffin of Mississippi introduced a bill, H.R. 156, essentially identical to the Timber Supply Act of 1969, but it failed to get a hearing. At about the same time, Oregon's Senator Mark Hatfield introduced the American Forestry Act, S. 350. It would have authorized a forestry incentives program to encourage forest development on nonindustrial private and State-owned lands; a forest land management fund for Federal lands based on timber sale receipts, similar to that in the Timber Supply Act of 1969; and an American Forestry Policy Board to counsel the Secretaries of Agriculture and the Interior on forest land policy. Senator Lee Metcalf of Montana introduced the Forest Lands Restoration and Protection Act, S. 1734, as an environmental analog to Senator Hatfield's bill, and Congressman John Dingell of Michigan introduced the same act as H.R. 7383 in the House. The latter bills focused on establishing rigorous regulatory requirements for both private and public forest lands, including the licensing of foresters and requiring that licensed foresters prepare mandatory harvest plans for private lands. "Sound forestry practices" were spelled out in detail for Federal lands, including the use of long rotations and the "even-flow principle" defined as "perpetual yield of approximately equal annual amounts . . . in quantities which do not decline and which may increase."

In 1973, during the 93rd Congress, Senator Sparkman introduced the Wood Supply and National Lands Investment Act, S. 1775, an updated version of the Timber Supply Act. Senator Hatfield introduced a revised version of the American Forestry Act as S. 1996. Both were referred to the Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry, which was deeply involved with a bill for a forestry incentives program for private nonindustrial lands and another bill banning log exports from Federal and non-Federal lands in the Pacific Northwest. The forestry incentives bill had wide support among most interest groups, and this consensus contributed largely to its eventual enactment. It authorized annual appropriations of $25 million to share forestry practice costs on non-industrial private woodlands of 500 acres or less.

The export of softwood logs from the West Coast to Japan became a public issue in the late 1960's, when softwood log exports threatened to rise above 2 bbf per year. Although almost all the export volume came from non-Federal lands, the Secretaries of Agriculture and the Interior in April 1968 issued joint orders restricting the volume of unprocessed timber that could be harvested and exported from national forests and BLM timberlands to 350 million board feet. No restriction was placed on the amount of "processed" timber that could be exported. The Secretaries' export quota was legislated and became effective January 1, 1969, and expired on December 31, 1973 (Hines 1987).

The proposal to ban log exports was seen as addressing symptoms rather than causes and was not considered a cure for the timber supply issue it addressed. It paved the way for other nations to retaliate. Even so, when the log export quota on Federal land expired in 1973, a provision attached to the Department of the Interior and Related Agencies Appropriations Act in 1974 and each year thereafter continued to prohibit the export of "unprocessed" timber harvested from Federal lands (Hines 1987).

The timber industry strongly supported both timber supply bills (S. 1775 and S. 1996). USDA supported neither. Reflecting the traditional position of OMB on the uncontrollable aspects of permanent trust funds, USDA insisted that it did not need a special fund based on national forest receipts to increase Federal forest management funding. The Sierra Club, Friends of the Earth, the Audubon Society, the National Wildlife Federation, the Wilderness Society, and the American Forestry Association likewise opposed both bills for their own reasons.

Instead of pursuing the highly polarized — conservation vs. timber industry — timber supply bills, the Committee on Agriculture and Forestry turned to a new proposal — S. 2296, the National Forest Environmental Management Act, which eventually became the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act of 1974 (RPA). The bill was written as a procedural measure rather than policy direction. Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota introduced it as an amendment to the 1973 Farm Bill. His purpose was to provide a participative, long-term planning approach to national forest management that would reduce the extreme differences between the timber industry and the environmental, conservation, and wilderness interests and the distrust of the Forest Service that had emerged in both groups in the preceding decade. He also wanted the process to circumvent the conventional short-run fiscal expediency in OMB's approach to Forest Service appropriations. Thus, S. 2296 did not specify any substantive policy or program goals for managing national forests; instead, it provided a process to develop management goals and a means to fulfill them using a modified budget process. Based on the President's commitment to support these management goals, this process could potentially ensure sustained and sufficient funding (Le Master 1984).

The Committee found S. 2296 too complicated and comprehensive to be added as an amendment to the already complex 1973 Farm Bill and proposed introducing a separate bill to explore the interest and support it would attract. Senator Humphrey agreed, but advised the Committee staff that the bill would need to have clear evidence of broad support. Responding to this guidance, the Committee staff, under the leadership of James Giltmier, invited concerned interest groups, including the timber industry, trade associations, conservation and environmental organizations, and the Forest Service, to define areas of agreement on the management of national forest lands. The groups included the American Forestry Association, the American Plywood Association, the Citizens Committee on Natural Resources, the Industrial Forestry Association, the National Forest Products Association, the National Wildlife Federation, the Sierra Club, the Society of American Foresters, Trout Unlimited, the Western Timber Association, and the Wildlife Management Institute. Participation was voluntary, informal, and free of any procedural requirement, and soon was down to reviewing and discussing S. 2296 line by line. In the process, the Forest Service disposition toward the bill shifted from "cooperative skepticism" to "enthusiastic support." Groups often characterized as preservationists, who were not originally included on this committee, later became major contributors (Le Master 1984).

Encouraged by the wide participation in the S. 2296 revision, Senator Humphrey introduced it in November 1973. The forestry community of interest widely endorsed and supported it. The title of the bill became the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act (RPA). It was literally the first legislative act to come before President Ford at a time when there was extreme tension between Congress and the Administration (Hirt 1994; Le Master 1984). OMB had sent a letter recommending that he veto it. The Secretary of Agriculture urged that he sign it, and he did so on August 17, 1974.

To assist in long-range planning, the RPA required the Secretary of Agriculture to conduct a comprehensive inventory and prepare an assessment of the Nation's forest and rangeland renewable resources every 10 years. The assessment was to summarize the inventory and analyze current and future demands and supplies for renewable resources from all forest and rangeland ownerships and describe Forest Service programs and responsibilities and discuss important policy considerations, laws, and regulations influencing forest and rangeland management. In addition, the RPA required the Secretary to prepare and transmit to Congress, by way of the President, a recommended renewable resource program every 5 years that provided for the protection, management, and development of the National Forest System, cooperative forestry assistance, and forestry research.

The program included specific needs and opportunities for investments, outputs and benefits, and management goals over a 50-year planning period. Congress, for its purposes, apparently considered 5 years the useful life of the RPA program, as they requested that it be updated every 5 years. Congress also required the President to submit a detailed statement of policy, intended to be used in framing Forest Service budget requests — a document that Congress could revise or modify. Congress has chosen to change this statement of policy only once, in 1980.

Sections 5 and 6 of the RPA specified three requirements for national forest lands and resources: A continuing, comprehensive inventory; the integration of national forest management plans with the national RPA program and coordination with corresponding State and local plans and those of other Federal agencies; and the use of a systematic interdisciplinary approach to integrate physical, biological, economic, and other considerations into national forest planning. In this way, the RPA linked, for the first time, national program planning directly to national forest land and resource management.

The RPA legislation did not explicitly provide for public participation, but Senator Humphrey called for a goals-oriented, open, participative planning approach to RPA. On September 19, 1974, he met with the interested citizens who had helped develop the Act and encouraged them and their organizations to participate in and support its implementation. To those present, he pointed out:

The Act gives you the means to set goals for the long-term and the short-term. This gives us the mechanism for sound planning.... The budget process is going to give us the muscle to reach our aspirations.... The President is entirely free to exercise his discretion, and I expect him to do just that. Likewise, Congress can do the same.... We are bringing program formulation to the people, and it will be up to them to embrace it.... We called this meeting to let you know you count; in order to make sure your ideas count; and to open the door for continued cooperation (Humphrey 1974).

The RPA was received with euphoria in forestry circles and viewed by some as a panacea for the forest resource issues that had been repeatedly analyzed and hotly debated for more than 5 years. The long-term planning it provided could have been, and had been, carried out under previously existing authorities, with one difference: the RPA provided for congressional endorsement of and interest in the policy analysis, program planning, and budget proposals the Forest Service developed under the RPA.

The RPA, in effect, was the solution the Forest Service sought to the ineffectiveness of its national program planning which was submitted directly to Congress in 1959, and its updated version, which was sent to Congress with a Presidential transmittal in 1962. Richard E. McArdle, Chief of the Forest Service from 1952 to 1962, who led the preparation of those early long-range program plans, strongly endorsed the RPA legislation in a Senate hearing in February 1974 (American Enterprise Institute 1974).

Administration Efforts To Increase Timber Supplies: 1970-1979

While Congress struggled with various legislative proposals to help national forest management respond to the Nation's needs, the timber and housing industry interests, and the environmental and conservation concerns, the Administration continued its own efforts to increase national forest timber supplies. In late 1969, the White House Interagency Task Force on Softwood Timber and Plywood completed its analyses of long-term alternatives for increasing timber supplies. But the White House, responding to the enactment of NEPA in January 1970, directed the Task Force to delay its report and work with the newly created Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) in the Executive Office of the President to give appropriate emphasis to environmental matters and work for legislation to increase timber supplies in ways that protected the environment. As a result of the polarization during the debate on the Timber Supply Act of 1969, the Task Force and Council judged that it would be next to impossible to obtain legislation. They felt the existing law was sufficient if it could be adequately funded and if the Forest Service and other Federal resource agencies could address the environment.

President Nixon endorsed and released the Task Force's final report in June 1970. The report found that the housing goals would require substantial increases in softwood timber supplies, without which wood product prices would rise substantially above 1962 to 1967 levels. The Forest Service felt that national forest allowable cut increases beyond an additional 7 bbf above the 1970 level would seriously threaten multiple-use and environmental objectives.

President Nixon directed the Secretaries of Agriculture and the Interior to work with CEQ to prepare plans for increasing the timber supply while meeting sustained-yield, multiple-use, and environmental quality objectives. He directed OMB to review any additional funding for such increases for consistency with overall national budget priorities. He further recommended that annual Federal timber sales be flexible and responsive to swings in demand; that USDA press ahead with programs to increase timber supplies from State and private lands; and that the Departments of Housing and Urban Development, Commerce, and Agriculture accelerate efficiency gains in wood product utilization. President Nixon also directed the naming of an advisory panel of outstanding citizens to study the entire range of problems to ensure that inadequate timber supplies did not preempt achieving national housing goals (Nixon 1970).

Responding to the President's direction, as a first step toward achieving the 7-bbf potential increase the Forest Service and the Task Force had reported attainable on national forests, the Forest Service prepared, and USDA proposed to OMB, a supplemental appropriation for FY 1971 to initiate a national forest investment program to increase softwood sawtimber harvests. This proposal was not approved. The 1970 timber demands had fallen to previously normal levels as a result of interest-rate increases and a decline in housing construction. OMB's review, obviously, reflected a very short-term view. In FY 1972, competing national priorities for the available Federal budget and constraints on budget outlay ceilings to reduce general inflation precluded any proposals for an accelerated national forest investment program. Although timber sales were programmed at the 1971 level, Congress approved additional funding to supervise the industry's accelerated harvest of previously bought, but uncut, national forest timber.

In 1971, the Cabinet Committee on Economic Policy reconvened the Task Force on Softwood Lumber and Plywood as housing construction and lumber and plywood prices rose to record levels in 1971 and 1972. President Nixon finally appointed his Advisory Panel on Timber and the Environment. This time the Administration viewed rising lumber and plywood prices as policy problems that affected the credibility of the President's Economic Stabilization Program.

Because raw materials such as timber were not subject to price controls and could be reflected in end-product prices as production costs, lumber and plywood prices were particularly difficult to regulate. For example, softwood prices for standing timber (stumpage) rose about 50 percent on national forests and 50 percent on private lands in the South while lumber and plywood prices rose only 12 and 16 percent, respectively. During the same period, the wholesale prices for all commodities increased by only 4 percent. Wood product prices continued their strong increases in 1973 and reached their highest levels in 1978 and 1979, years when timber stumpage prices and speculation were also at their highest, new household formations were nearly 2 million per year, and construction of new housing units exceeded 2 million per year.

Despite its earlier analyses of housing goals and the timber supply issue, the President's recommendations, and the Administration and Forest Service responses, the reconvened Task Force found that none of the President's recommendations had been implemented except his appointment of an Advisory Panel on Timber and the Environment. Thus, the Task Force quickly concluded that further analyses would add little to the assessment of the timber supply issue or to its proposed solution. It recognized that funding was the key to short- and long-term timber supply increases from Federal lands and urged the Director of the Cost-of-Living Council, which was administering the President's Economic Stabilization Program, to make every effort to find a solution to the inflating lumber and plywood prices and the timber supply issue.

For the FY 1973 programs, budget constraints to contain inflation again squelched any chance that the Forest Service could intensify its management and increase its timber sales. National forest timber sales and harvests remained at FY 1972 levels during FY 1973, but the Secretary of Agriculture and the Director of the Cost-of-Living Council announced plans to increase timber sales by a billion board feet by FY 1974. After a delay, Congress finally approved this proposal and the Administration requested a $15 million supplemental appropriation to fund it. The Natural Resources Defense Council, the Sierra Club, and the Wilderness Society responded with a suit to enjoin the Forest Service from increasing FY 1974 timber sales, and in February 1974 a Federal Court ruled that the congressionally approved billion-board-feet sales increase was illegal without an EIS.

The President's FY 1975 budget included the proposed billion-board-feet increase that Congress had funded. In April 1974, the same environmental and wilderness groups, plus the National Parks and Conservation Association, filed suit against the increase. They asked for a declaratory judgment that the entire FY 1975 Forest Service RPA national forest program beginning on July 1, 1974, violated NEPA by failing to file an EIS. The National Forest Products Association, sensing the suit would shut down or delay timber harvests, became an intervener in the suit. The Association denied that the proposed FY 1975 budget was a legislative proposal or other Federal action that would significantly affect the environment under NEPA. The suit was settled when all parties agreed that the 1975 RPA assessment and program would serve the purposes of an EIS.

Report of the President's Advisory Panel

President Nixon endorsed the Advisory Panel's report in September 1973. The report supported increased timber harvests from national forests, but only with assured sustained financing for the intensified management needed to achieve higher timber harvest levels. It recommended a generous withdrawal of roadless areas qualified for wilderness preservation as well as withdrawing lands with fragile soils and steep, erodible slopes from the timber harvest land base. It supported expanding recreation areas and protecting water supplies, wildlife, and rare and endangered species. The Panel asked that commercial forest lands (CFL) not set aside for wilderness or other uses be designated for timber production and recommended a National Forest Policy Board to advise the President, the Congress, and the Nation.

The American press widely interpreted the Panel's report and the President's endorsement as recommendations to increase national forest timber harvests. The timber industry praised the report; environmentalists severely criticized it. The New York Times, like the Sierra Club and other environmental groups, viewed the allowable cut on national forests as already too high and, therefore, saw the President's endorsement of a harvest increase as "reckless" policy. The environmental interests took sharp exception to the Panel's support of clearcutting and designating CFL not withdrawn for wilderness or other uses for timber production. The American Forestry Association and the Forest Service likewise opposed designation of nonwithdrawn lands for timber production and the proposal for a National Forestry Policy Board as well. The Ford Administration, reporting the Panel's recommendations and follow-up actions to Congress in 1974, also opposed the Policy Board. Because the RPA process involved the public, the Executive Branch, and the Congress and provided a framework for a systematic, orderly analysis of an array of complex issues, the Ford Administration viewed it as a sufficient opportunity for review and development of forest policy.

Some of the press viewed the Advisory Panel's qualification that national forest harvests be accelerated only if more Federal funds and staff were provided as a stumbling block to both the Administration and the Congress (Washington Star-News 1973; Science 1973). The American Forestry Association (AFA) was more sanguine:

The biggest needs of the national forests ... are adequate funding and a long-range plan ... and while recommendation nineteen proposes an increased annual Federal expenditure for forest development ... of $200 million, AFA believes ... it should be reaffirmed in each of the other 19 recommendations in words that the White House, the Office of Management and Budget, and the Congress could clearly understand.... (American Forests 1973)

William E. Towell, Executive Vice-President for the AFA, wrote elsewhere:

The name of the game is funding. It does little good to get new forestry programs authorized unless the money is provided.... Somewhere in the wave of new environmental enthusiasm traditional forestry and wildlife conservation programs have not kept pace in the struggle for tax dollars. New [environmental] projects ... have drained off available funds. These efforts are all good and deserve our attention, but we cannot continue to slight fundamental forestry and wildlife activities.... If money is the name of the game, then let's get our signals straight for the opening kickoff (Towell 1973).

An Independent Effort for Consensus

In the foregoing setting, Marion Clawson, a member of the President's Panel and author of its report, continued his pursuit of a successful resolution to the timber supply and funding issue. In May 1974, he organized the Resources for the Future Forum on "Forest Policy for the Future: Conflict, Compromise, Consensus" (Resources for the Future 1974). Forum organizers were convinced that a substantial consensus on forest policy was both desirable and possible and would be advanced by an exchange of views among concerned persons and interest groups through an open, mutually shared search for a constructive forest policy. Resources for the Future invited more than 200 participants from Congress, the Executive Branch, the timber and building industries, labor unions, universities, and environmental, conservation, and wilderness organizations.

The Forum did not define policy issues in advance. Instead, it addressed the future demand for forest products and services and conflicts and strategies in forest land management in the first two sessions. A third session addressed the administration and financing of forestry programs. The final session was "A Search for Consensus."

The former president of Resources for the Future and U.S. Congressman from Virginia, Joseph L. Fisher, defined consensus as "not a perfect agreement on figures or statements, but rather a shared understanding of what the issues are, pros and cons of the solutions proposed, and the directions in which to go" (Fisher 1974). He identified the question of how much forest land for wilderness versus how much land for timber production as the principal issue on which consensus was lacking. In dealing with this issue, he thought the country was on the right track, but moving ahead with much backing and filling and grinding of gears. He attributed this difficulty to a lack of confidence and trust among antagonists; it would not be dispelled easily.

The closing session centered on areas of present and potential agreement and those where agreements did not seem possible. William Towell proposed that the interest groups concentrate their efforts on areas of present agreement and avoid areas of major differences. He recommended expansion of program funding for national forest programs as the highest priority issue on the basis of widespread agreement among forest conservation groups that these programs were underfinanced and out of balance with each other and total funding needs. A representative of wilderness interests suggested that the area of concentration be on issues where differences were the greatest. Wilderness did not require major budget expansions; thus, in his view, funding was not an area for a common effort. The Sierra Club could not go along with the AFA's long-range planning and funding goals until the wilderness issues were resolved. The wilderness representative said, "you cannot get agreement with environmentalists for more funding if it represents a threat to wilderness and old-growth forests" (Fisher 1974).

The consensus discussion ended without agreement following a strong statement from William R. Hagenstein, Executive Vice President for the Industrial Forestry Association and former president of the Society of American Foresters. He felt the Nation already had plenty of good forest policies, and he cited many. He concluded that the principal need was to give the Forest Service the tools it needed to get the job done. This appeared to be an endorsement for greater Forest Service funding for all resource purposes including designating new wilderness areas, intensifying forest management, and expanding the Federal timber harvest.

The RPA's enactment a few months later effectively shifted the approach to resolving the national forest management and funding issues. The Forest Service would conduct the RPA assessment and program planning process and prepare a national forest program and the accompanying EIS with public participation. The USDA would review it and approve it. It would then be reviewed by OMB and the President, who would transmit it to Congress along with his statement of policy for its implementation. All Forum participants would have the opportunity to participate in the RPA process.

The Performance of Timber Supplies and Housing Goals in the 1970's

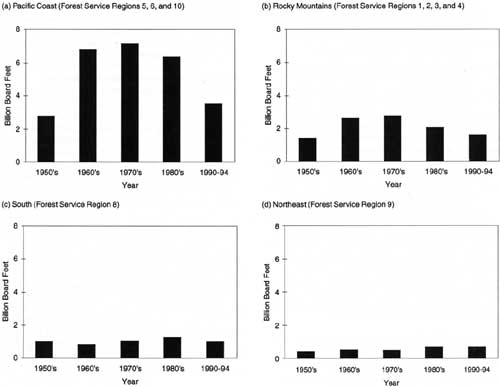

During the 1970's, national forest timber sales averaged 11.0 bbf per year — a reduction of 300 million board feet from the average annual sales volume of the 1960's — and did not vary much from year to year (fig. 14) Thus, when housing construction was at record levels, averaging 2.15 million units, and total timber product consumption rose 30 percent, national forest timber sales did not contribute to any increase in timber supplies.

|

|

Figure 14. Average annual national forest harvest by decade for major

U.S. regions, 1950-19941 1First half of the 1990 decade only. Source: USDA Forest Service. |

The average annual timber industry harvest of national forest timber in the 1970's was 11.4 bbf per year — 400 million board feet more than the average annual sales volume. The industry achieved this high average annual harvest level by accelerating harvests of national forest timber it had bought and had not yet cut in the first half if the 1970's. In the latter half of the decade, however, the timber industry reduced its harvest to an average of 10.6 bbf per year — 400 million board feet less than the average annual timber sales volume for the decade — even though housing construction in the 1977 to 1979 period was near peak levels.

Although much of the pressure to expand national forest timber supplies had come from the western forest timber products industries, the West did not share equally with southern or Canadian producers in the expanded softwood lumber and plywood markets. As the U.S. timber and construction industries geared up to meet the national housing goals of the 1970's, total annual softwood lumber and plywood consumption in the United States increased by 18.3 bbf, or 34 percent, from 38.6 bbf in 1969 to 51.9 bbf in 1978. Softwood lumber net imports, primarily from Canada, supplied 42 percent of the increase, or 5.6 bbf. Southern softwood lumber and plywood production provided 5.7 bbf of the increase, or 43 percent. The balance of the increase in consumption, just 2 bbf, or 15 percent came from the western regions. In the Western States, both industry and other private landowner softwood timber inventories were generally declining, which limited their capacity to expand their timber supplies. Log exports, mainly to Japan, increased from 2.7 bbf in 1970 to 3.8 bbf in 1979, which also limited the expansion of domestic supplies from western mills. Thus, in the 1970's, western national forests became a potential source of increased timber supplies that could, with a higher intensity of timber management, be made available to the western timber industry. However, national forest timber sales for the 1970's actually remained slightly below those for the 1960's.

More than 21 million new housing units, including mobile homes, were added to the national housing inventory between 1969 and 1978 — a substantial fulfillment (more than 82 percent) of the 26 million unit goal of the 1968 Housing Act. A record number of families obtained new housing during this period. Housing contractors built more homes than ever. Residential construction jobs expanded and workers were fully employed. Realtors sold more new homes than in any previous decade. Financial institutions made a record number of new housing loans. Forest industries had no complaint about profits. Lumber dealers sold record amounts of lumber and plywood. National forest timber harvests were slightly reduced from the 1960's, the number and area of designated wildernesses were expanded, and de facto wilderness and roadless areas were being protected by NEPA requirement for an EIS. National recreation areas, national trails, and wild and scenic rivers were expanded in number and area.

The Clearcutting Issue Leads to New Guidelines for

Managing Multiple Uses

Clearcutting had become a controversial public issue on a number of national forests during the late 1960's and reached national proportions in 1970. Congressional hearings in 1971 produced new administrative guidelines for clearcutting on national forests, and these were first applied in 1972. However, a court suit in 1973 to enjoin clearcutting on West Virginia's Monongahela National Forest led to a ruling that clearcutting practices were inconsistent with a literal interpretation of the 1897 Organic Act's timber harvesting guidance. The result was an injunction in the Fourth Circuit Court against such cutting, which applied to all national forests in Maryland, West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. If this injunction had been extended to all national forests, it would have reduced timber availability from western national forests by 50 percent. A search for legislative solutions to the clearcutting issue eventually resulted in the passage of the National Forest Management Act of 1976 (NFMA). The process of resolving the clearcutting issue is reviewed here.

Early National Forest System Response to Clearcutting Critiques: 1970

Opposition to clearcutting on national forests emerged in the late 1940's and 1950's as harvest levels steadily rose and clearcutting as a method for harvesting and regenerating commercial timber stands became more widely used. During the 1960's, the opposition to clearcutting became more widespread over the National Forest System and more intensified in certain regions and on certain national forests. In 1970, clearcutting became a national issue with four focal points of sharp controversy: West Virginia's Monongahela National Forest, Montana's Bitterroot, the Bridger and several other forests in Wyoming, and Alaska's Tongass.

Most of the opposition came from local citizens and a variety of local use and interest groups, who often had the support of local and State conservation, recreation, and wildlife, and related interest organizations. By 1970, however, the clearcutting issue had engaged the attention and activities of national environmental and conservation groups as well as Representatives and Senators who represented the local interests.

Critics' objections were wideranging. They argued that clearcutting destroyed wildlife habitat and caused erosion that damaged fisheries and degraded soil and water; produced unsightly landscapes and degraded scenic values; destroyed plant and animal diversity; threatened irrigation water supplies; involved overcutting in violation of the sustained-yield principle; and impaired various recreation uses and experiences. Critics also felt that national forest managers were slow in responding or unresponsive to their concerns and seldom consulted with them before implementing clearcuts. In 1965, the growing opposition led the Forest Service to mount a program to explain to the public its view of clearcutting as an effective tool of the even-aged silvicultural management method for wood production, forest regeneration, and resource management. This effort attempted to clarify apparent public misperceptions about clearcutting. The Forest Service misread its audience, because citizens believed clearcutting was a real problem for other reasons. In fact, the effort polarized some of its critics (Weitzman 1977; Cubbage et al. 1993). In many ways, the rising controversy suggested that national forest management was losing its way in heeding the guidance of Gifford Pinchot (1907):

There are many great interests on the national forests which sometimes conflict a little. They must all be made to fit into one another so that the machine runs smoothly as a whole. It is often necessary for one man to give way a little here, another a little there. But by giving way a little at present they both profit by it a great deal in the end.

National forests exist today because the people want them. To make them accomplish the most good the people themselves must make clear how they want them run.

In-Service Evaluation of the Clearcutting Issue on Selected National Forests

As the controversy over clearcutting intensified on the Monongahela, Bitterroot, and four national forests in Wyoming, the Forest Service appointed special task forces to review the clearcutting critics' charges and evaluate the applied management practices and their effects. These evaluations were commissioned by the regional forester for the Northern Region for the Bitterroot; jointly by the regional foresters for the Rocky Mountain Region and the Intermountain Region for the Bridger, Teton, Bighorn, and Shoshone National Forests in Wyoming; and by the Chief of the Forest Service for the Monongahela in West Virginia. No study was undertaken on Alaska's Tongass National Forest, where the Sierra Club sought an injunction against the long-term timber sale contract — 8.75 bbf in a single long-term sale — and a declaration that the Tongass had violated the MUSY Act by administering its lands predominantly for timber production. The basic harvesting method was clearcutting.

The Forest Service staffed each of these studies with experts who had not been involved with the clearcutting in question or the public issue. The experts represented a range of resource management activities. They were directed to provide an impartial, but thorough, analysis. As they initiated their investigations, they consulted with national forest managers responsible for each forest and with local citizens critical of clearcutting. They also received written responses and statements from the citizen critics.

The task forces found and reported evidence of substantial shortcomings in the way clearcutting was applied. For example, the Bitterroot Task Force reported, "Clearcutting has been overused in recent years. In many cases esthetics have received too little consideration. It is apparent to us that a pre-occupation with timber management objectives has resulted in clearing and planting on some areas that should not have been clearcut" (USDA Forest Service 1970). The Monongahela Task Force reported that emphasis on timber management was leading to an imbalance among its resource programs (Weitzman 1977). The Wyoming National Forests Task Force reported similarly:

We found much evidence of good management, but we also found indications of serious shortcomings. There was some evident damage to wildlife habitat and to soil stability. More frequently, a potential for such damage was clear. . . . Damage to the scenic quality of the landscape, however, was unmistakable.

The report further elaborated:

The conflict between timber and other values is evident. These operations, carried out some years ago, have been roundly criticized, not only by the public but also by members of the timber industry and the Forest Service... . We believe there have been inadequacies in planning, in execution, and in evaluation of management actions on all four of the Wyoming Forests.. . . (USDA Forest Service 1971a).

All of the reports found shortcomings in multiple-use planning. The Bitterroot Task Force reported:

Multiple-use planning . . . has not advanced far enough to provide firm management direction necessary to insure quality land management and, at the same time, to provide all segments of the public with a clear picture of long-range objectives. (USDA Forest Service 1970)

The task forces recognized and reported that management shortcomings affirmed many of the local citizens' concerns about clearcutting. They made straightforward recommendations to remedy these shortcomings and avoid them in the future. But they also acknowledged that much of the management they observed on the study forests was quite adequate.

The task forces looked for deficiencies in management planning and implementation. They found that the emphasis on achieving short-term production targets often took precedence over longer-term land management. The Bitterroot Task Force report stated it this way: "there is an implicit attitude among many people on the staff of the Bitterroot National Forest that resource production goals come first and that land management considerations take second place." The Bitterroot report found that such emphasis was not unique to the Bitterroot and that it did not originate at the national forest level. It attributed this emphasis to "rather subtle pressures and attitudes coming from above" (USDA Forest Service 1970).

|

| Timber regeneration harvest, Snoqualmie National Forest, Washington, 1970. Immediate foreground shows excellent reproduction of Douglas-fir, western red cedar, and noble fir following 1952 clearcut. Background shows more recent clearcuts logged with high-lead cable systems. Intermediate ground shows a shelterwood harvest. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library.) |

The task forces saw that the pressure to sell the full allowable cut each year to make more timber available and ease the housing materials shortage was most insistent. The Washington Office required weekly timber sale accomplishment reports to keep the Secretary of Agriculture, Congress, and outside groups informed of progress in meeting timber cut commitments — evidence of pressure from above to meet timber targets — although at the time such production control was normal in most well managed business enterprises. Other factors contributing to shortfalls in forest resource management were related to lack of basic resource information; lack of specialized skills at the forest level in important disciplines such as landscape management, wildlife biology, soils, and hydrology; and shortfalls in quality control (no or insufficient monitoring of management activities). In a search for deeper causes, the task forces identified underlying problems of heavy workloads; shortages and frequent transfers of professional staff; youthful, less-experienced staff; and insufficient financing.

The Wyoming Task Force found that foresters with inadequate training and experience in silviculture and multiple-use coordination were making field on-sale layout and harvesting decisions because senior foresters were burdened with too many other essential duties, including NEPA compliance appeals, to give detailed assistance to these field tasks. Heavy current workloads limited opportunities to evaluate and monitor the effects of past management. The Task Force found this deficiency most obvious in assessing regeneration success, which was often found wanting.

The Bitterroot Task Force's check on the depth of experience and strength of the Forest's land management capability found that the average length of service of professional employees was 11.5 years within the Forest Service, but only 3 years and 2 months on the Bitterroot. The shortness of this experience was associated with the Forest Service's rapid growth in the 1960's — a transitional and unavoidable problem. However, the district ranger's short tenure on the forest was also associated with the Forest Service's practice of frequent transfers to broaden and accelerate the development of its foresters as managers. Broad experience was important for managerial strength in senior positions, but frequent transfers also contributed to less depth of experience for executing on-the-ground fieldwork.

|

| Shelterwood harvest, Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon, 1970. Harvest removes enough trees for Douglas-fir to regenerate itself and leaves enough trees to provide a seed source and shade to protect seedlings from frost damage. Overstory will be harvested when seedlings are established. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library.) |

The task force reports revealed that the National Forest System and Forest Service research had adequate knowledge and capability to recognize and evaluate poor management practices and multiple-use coordination after the fact. The difficult challenge was to correct the different practices and coordination procedures and avoid such shortcomings in the future. The Forest Service Washington Office directed the regions and forests to take corrective action at the local level. But the speed and thoroughness of this local action was limited by staffing, funding, and policy that were beyond local control (Weitzman 1977). From this perspective, the Congress, the Administration, USDA, and the Forest Service's Washington Office were part of the problem (as well as part of its solution).

Chief Cliff Gives Emphasis to the Ecosystem Approach and Training

By 1970, the Forest Service hierarchy was well aware of the growing public concern and the rising number of open conflicts over how the national forest resources, especially timber, should be used and managed and the need for change. Chief Ed Cliff highlighted the challenge for more effective multiple-use and resource management in this way, when he spoke to the regional foresters and station directors on January 19, 1970, as quoted in the Bitterroot National Forest Task Force Report:

I am convinced that with an ecosystem approach to multiple-use management, our forests and rangelands can contribute to a better living for present and future generations by providing security and stability to regional economies and rural communities. It can also provide a high-quality environment, recreation opportunities, fish, wildlife, water, forage, and timber, and be in harmony with the needs of lesser organisms. But the use of the resources must be balanced with the constraints of stewardship responsibility for we are dealing with a limited land and natural resource base (USDA Forest Service 1970).

|

| Edward R Cliff. Chief of the Forest Service, 1962-1972. (Forest Service Photo.) |

In June 1970, the Deputy Chief of the Forest Service, M.M. "Red" Nelson, wrote to regional foresters, advising them to help improve the ecological skills of national forest professionals and suggesting some first steps to do so:

Much is happening in ecology. The ecosystem concept is being dusted off. It now forms a popular and conceptually sound basis for management planning. Energy flows in the ecosystem give us one way to look at and predict the impacts of management actions. Functional ecology is now being emphasized above descriptive ecology in our better universities. In the face of this dynamic situation, we need to examine how well-honed our ecological skills are.

Another vehicle we are testing is taped briefs of research that we should be aware of. The task of achieving agency leadership in ecology has got to include personal commitment by each Forest Service professional. Each of us has got to do what he can do to update our own professional competence. One way is by selected reading (Nelson 1970).

The readings included the six up-to-date references on ecology, ecosystems, and resource management: Readings in Conservation Ecology, edited by George W. Cox, 1969; Perspectives in Ecological Theory, by Raymond Margalef, 1969; Environmental Conservation, by Raymond P. Dasmann, 1968; The Ecosystem Concept in Natural Resource Management, edited by George M. Van Dyne, 1969; Concepts of Ecology, by Edward J. Kormondy, 1969; and Ecology and Resource Management: A Quantitative Approach, by Kenneth E.F. Watt, 1968. Regional foresters passed this guidance on to national forest supervisors:

The ecosystem has always formed a sound basis for natural resource management planning. Energy flows in an ecosystem are analogous to cost-benefit flows in an economy. There is plenty of economic conscience in the Forest Service. Our ecology conscience could stand improving. The Washington Office is distributing the new book by Dr. Edward J. Kormondy entitled Concepts of Ecology to help us relate this subject to our responsibilities. We heartily endorse this approach to increased professional competence and agency leadership. The book by Kormondy is attached for your use (Cravens 1970).

A Nationwide Field Evaluation of National Forest Timber Management

During 1970, Chief Cliff directed a team of Forest Service experts representing water, timber, wildlife, and landscape (and other recreation resources) to prepare a nationwide field evaluation of timber management practices and related national forest activities. The team's report was to highlight problem situations and pave the way for responsive actions that would attain and maintain a high level of timber productivity and environmental quality. Nothing less would be acceptable. In October 1970, when the team was evaluating timber management practices on national forests, the Chief wrote in an interoffice memorandum to all Forest Service employees:

Our programs are out of balance to meet public needs for the environmental 1970's and we are receiving mounting criticism from all sides. Our direction must be and is being changed.... The Forest Service is seeking a balanced program with full concern for the quality of the environment (Cliff 1970).

The report, National Forest Management in a Quality Environment: Timber Productivity, was completed and delivered to the U.S. Senate in April 1971, as the Subcommittee on Public Lands was holding hearings on management practices on public lands. The report identified 30 problem situations where national forest clearcutting practices were being misapplied or producing undesirable adverse effects that needed to be responded to. Cliff advised the Subcommittee that the Forest Service was ready to make the changes in policy and practices the study recommended (Cliff 1971). Making these changes, however, would require more detailed information on what had to be done in each of the 30 problem situations. (Cliff 1971; USDA Forest Service 1971b).

Congressional Hearings Elevate Clearcutting to a National Issue: 1971

National forest managers, however, were not to have the time to define and develop the changes Chief Cliff had identified. The clearcutting controversy was suddenly elevated to a "full blown" national issue in late 1970 and early 1971 and became the subject of hearings by the U.S. Senate Interior and Insular Affairs Committee's Subcommittee on Public Lands, chaired by Senator Frank Church of Idaho. An event that contributed to the national escalation of this issue was the completion of a report on the management of the Bitterroot National Forest prepared by the Select Committee of the University of Montana Faculty ("A University View of the Forest Service," November 18, 1970) and the Subcommittee's wide distribution (20,000 copies) of that report (U.S. Senate 1970). Montana Senator Lee Metcalf, a member of the Subcommittee and a resident of the Bitterroot Valley, had requested the report. He felt the University study would give an appropriate external review of the Bitterroot Valley citizens' complaints about the Bitterroot's timber management practices and serve as a useful complement to the largely technical internal Forest Service study.

The study objective was defined in this way: "to determine what the Forest Service ought to be doing, what it was doing, and whether its actions indeed departed from what it ought to be doing" (Bolle 1989). The University of Montana Select Committee elevated its analysis and report to a policy evaluation of the actual management practices against the management of multiple uses as defined in the MUSY Act. The University report used the Bitterroot Task Force report as a starting point for its factual findings. While it acclaimed the Task Force critique of timber management practices, it felt the Task Force gave "short shrift" to related range, watershed, wildlife, and recreation issues (Bolle 1989) and cited the "psychological impossibility of objectively criticizing one's own efforts" (Popovich 1975). The Select Committee saw the real problem as timber primacy dominating and controlling Forest Service activity. It interpreted this as a clear departure from the congressional policy of multiple use as defined in the MUSY Act. The Select Committee's report charged that "Multiple use management, in fact, does not exist as the governing principle on the Bitterroot National Forest" (U.S. Senate 1970).

The Select Committee found that the Bitterroot's terracing and planting practices following clearcuts on low-productivity fragile mountain slopes, the specific target of much of the Bitterroot Valley residents' criticisms, to be uneconomical and therefore, unjustified, even though they were usually effective for regeneration. In place of this extreme and costly practice, the Select Committee recommended "timber mining" — the harvesting of the commercially valuable timber and suspension of any purposeful regeneration efforts altogether. The Forest Service unrelentingly rebutted this recommendation. It was also questioned by many foresters and Bitterroot Valley residents, who saw "timber mining" as an absolutely alien approach to forestry (Popovich 1975).

The Select Committee found that clearcuts were too large and often used where other silvicultural systems were more suitable. The Committee found that congressional appropriations were inadequate for balanced resource management and insufficient to remedy the problem. It saw a need to add economists and other resource specialists to the Bitterroot management staff, the need to openly solicit public participation and become more responsive to it, and a need to find ways to reward and retain competent timber sales supervision and other field operations employees as opposed to promoting them to office jobs removed from field activity.

The release of the University report in late 1970 at a national press conference brought startling results. Virtually overnight the earnest concerns of the Bitterroot Valley residents were flashed coast to coast. Not only did stories appear in the national press, but seemingly in every newspaper in the Nation and some in Europe and Africa (Bolle 1989). The report findings became startling nationwide news and contributed to escalating the clearcutting controversy to a national issue. National attention was focused on both national forest management and the Forest Service as a natural resource managing agency.

|

| Selection forest with uneven-aged structure being formed by periodic partial harvests in a northern hardwood stand, Nicolet National Forest, Wisconsin, 1970. Next planned harvest was scheduled for 1985. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library.) |

The Senate Subcommittee on Public Lands scheduled hearings on clearcutting for 5 days during 1971 (U.S. Senate 1971). More than 90 witnesses were heard; many more provided written statements. The Subcommittee also received thousands of letters from all parts of the country expressing interest in the future of the Nation's forests. Witnesses included Members of Congress, environmentalists, State officials, professional foresters and other scientists, timber and housing industry representatives, the Forest Service, BLM, and HUD.