|

Managing Multiple Uses on National Forests, 1905-1995 A 90-year Learning Experience and It Isn't Finished Yet |

|

Chapter 5

Performance of Multiple-Use Management: 1970 to 1979

This chapter describes the national forest on-the-ground response to the growing demands for multiple uses and the rising pressures for greater environmental sensitivity and protection. It presents a fuller view of the setting for and national forest managers' response to the national policy issues of the 1970's and new congressionally enacted policy direction. Overall, national forest managers continued to respond to the expanding national and local national forest use demands but struggled to implement the new policy direction and the environmental and ecosystem emphases that were rapidly evolving from the national debates and public pressures.

The Internal Forest Service Setting: The 1970's

By 1970, many national forest managers and professional staff were deeply concerned about the direction national forest management was taking. Chief Cliff shared these concerns in a memo to all Forest Service employees (Cliff 1971a). He pointedly reported that programs were out of balance with the public's emerging environmental preferences and that criticisms were mounting on all sides. The national forests needed new direction, and the Forest Service was taking steps to achieve such changes. He cited the draft Environmental Program for the Future (EPF) as a leading initiative to shape these changes — through higher and more balanced congressional funding. The Chief stressed the need to heed President Nixon's response to the Softwood Timber and Plywood Task Force findings to intensify management to increase national forest timber supplies while protecting environmental quality. He also reiterated NEPA's strong requirements and the President's direction that Federal agencies carry out full pollution abatement on all Federal projects promptly.

The Chief felt the key to successfully achieving a more balanced resource emphasis and the new NEPA objectives was increased staffing and funding (Cliff 1971a). If such increases were not feasible, then current activities would have to be reprogrammed: timber sales, road construction, and structural improvements would need to be reduced; funding for wildlife, watershed, recreation, pollution control, and similar activities would need to be increased.

In July 1971, Chief Cliff summarized the public's view and outlook, as he saw them, before a joint meeting of the Western Association of State Game and Fish Commissioners and the Association of Midwest Fish and Game Commissioners in Aspen, Colorado:

The American public is demanding top quality in the management of natural resources and attention to the way things look. We are already involved in a number of lawsuits reflecting public awareness of our activities. The public is increasingly unhappy with us. This will continue until we get balance and quality into our program, as well as public involvement into our decisions. Until we do this, the course of the public entering into our fairly routine decisions through protests, appeals, and court cases will have the effect of reducing our ability to put timber on the market to help meet housing goals (Cliff 1971b).

Earlier, in January 1970, Chief Cliff had told regional foresters and experiment station directors that he was convinced that an ecosystem approach to the management of national forest uses would contribute to a better life for present and future generations. This approach would provide a high-quality environment for recreation opportunities, fish and wildlife, water, forage, and timber in harmony with the needs of lesser organisms. He encouraged his staff to review the current ecology and ecosystem management references and to participate in a national training program on ecosystem approaches to national forest management.

Following the traditional division of policy and management responsibilities between the national and field offices and the decentralized approach to managing multiple uses, the implementation of this approach and related training was left largely to regional foresters and forest supervisors and their professional staffs. Washington Office leadership would not refocus its multiple-use resource-management policy attention to the ecosystem approach explicitly again until the 1990's.

|

| C. Wayne Cook, Professor Emeritus of Range Science, Colorado State University, and the driving force in the introduction and development of the Ecosystem Management short course in the late 1960's. (Colorado State University.) |

National Forest Managers' Training in Ecosystem Management

Chief Cliff's views for linking the ecosystem approach to managing multiple uses on national forests were translated into a national ecosystem management training program for national forest managers. This program began in 1970 through joint Forest Service sponsorship of an Ecosystem Management Short Course with the Department of Range Science at Colorado State University. At that time, it was the first formal ecosystem management course offered at the university level in the United States (Cook 1994).

The Forest Service sponsorship led to substantial course additions and its expansion from 2 to 3 weeks. It was initially offered three times per year — later reduced to two weeks and two sessions per year — with a minimum of 35 students per session. Forest Service sponsorship continued into the early 1980's, when the program was superseded by the national training program for National Forest Management Planning. In the 12 or so years that it was offered, nearly 1,000 national forest managers and staff experts from the Chief's level down to the ranger district participated in it. Over the years, Forest Service participants made up more than 80 percent of the total enrollees (Cook 1994). Many Ecosystem Management Short Course graduates became trainees in the national forest management planning training program in the 1980's. Such enrollees provided a bridge for linking ecosystem management principles with national forest planning.

The range management background of many of the course instructors and the Department of Range Science influenced the general context of the course — forested and open rangelands — but it also addressed wildlife, timber, water, recreation opportunities, and related uses. The teaching focused on ecological principles and theory, with a strong emphasis on ecosystem structure and functions. The course's objective was to provide a generalized understanding of how ecosystems responded to different natural and anthropocentric influences and the importance of maintaining the integrity of ecosystem structure and functions. Instructors often supplemented this training with case studies and field observations. (Bartlett 1994; Cook 1994; Colorado State University undated).

The Washington Office did not furnish any central guidance for applying the ecosystem approach to managing national forest resources during the 1970's. Ecosystem principles were implemented by the trainees who took what they had learned about ecosystem functions and structures and applied it as they saw fit in their daily management work on the national forests. Ecosystem approaches to national forest resource management developed most strongly in connection with range and wildlife. But this emphasis naturally influenced the management of other resources — particularly timber. Early applications of an ecosystem approach within the National Forest System were quite uneven. They were hampered because managers saw uncertainties and risks with such applications, especially the barriers of the Forest Service's detailed manuals and management guides. Where ecosystem-oriented efforts deviated from manual guidelines and led to unacceptable results, or where supervisors saw aberrations from established guidelines, the ecosystem approach carried career risks for young foresters, resource specialists, and managers (Hartgraves 1994).

Even though the ecosystem approach was not formally adopted, there were many efforts and initiatives to incorporate its principles into managing national forest uses (Hartgraves 1994). One of the most important initiatives established a common framework for classifying National Forest System lands and resources by ecosystem characteristics. An ecosystem approach to national forest management needed to stratify forest and rangeland ecosystems as they lay on the land.

|

| Ecosystem Management short course participants received field instruction and experience to better understand the concept of ecosystem management. Field trips examined both rangeland and forested ecosystems. (Harold Goetz, Range Ecosystem Department, Colorado State University.) |

Classifying National Forest Lands and Resources

In the early 1970's, when national forest unit planning was getting underway, the Intermountain Region's regional forester initiated a project to provide a common framework for classifying heterogeneous lands and resources on the region's national forests. At that time, each functional staff had its own particular approach to land and resource classification and each forest developed its own classification system to fit its specific conditions. Such classifications were influenced by the particular background, training, and experience of the resource staff developing them. The goal of the Intermountain Region's project was to develop a common classification framework that would consistently predict management responses, distinguish ecosystem productivity differences, and be useful for timber, wildlife, fish, watershed, range, recreation planning and management, and the integration of multiple uses across the region (Sirmon 1994).

Robert Bailey, the Intermountain Region's ecological geographer, led the project. He mapped ecoregions (extensive geographical zones over which the macroclimate is sufficiently uniform to permit the development of similar ecosystems on sites with similar properties). Within the same ecoregion, such broad-scale landforms as mountains and valleys, extensive water bodies, swamps, or broad plains modified the "local" climate and led to secondary differences in the ecoregion structure and components. Ecoregion substratifications due to landform were called "landscapes." Due to different geographic patterns, an ecoregion could contain many landscapes. With this understanding of the relationship between climate and landforms, national forest resource people could consistently delineate and differentiate ecosystem units at several different scales depending on their needs and purposes and upon which questions decisionmakers at various levels would be asking. The variously sized ecosystem units provided a base for consistent estimates of ecosystem productivity, probable responses to management practices, and the interaction effects of such management among ecosystem units (Bailey 1983; 1987a). Because ecoregions and ecosystems units did not follow National Forest System boundaries, Bailey's approach was broadened to cover all ownerships.

In 1976, the Forest Service published the first map titled "Ecoregions of the United States" for the Department of the Interior's Fish and Wildlife Service, a cooperator in the project, to help compile its National Wetlands Inventory. The same map was used in the RARE II process to assess which eco-regions and lower level ecosystem components were not already represented in designated wildernesses.

Bailey's map was later used to identify and locate ecosystems not represented or underrepresented in the National Wilderness Preservation System. The Intermountain Region used Bailey's process in unit area planning and eventually in national forest land and resource management planning. Other regions also used the map, but in the absence of any central consistent direction within the National Forest System, each region applied different or additional criteria for its particular purposes.

National direction for implementing an ecosystem approach to managing multiple uses was to come almost two decades later in 1992, with the further development and refinement of the ecoregion framework and the technology for mapping lower level ecosystem units. In November 1993, David Unger, the Associate Chief of the Forest Service, issued a directive, "effective immediately," to begin using the National Hierarchical Framework of Ecological Units in land management planning, research programs, and cooperative efforts with other agencies and partners (Unger 1993; USDA Forest Service 1993a). This framework has been adopted by several Federal and State resource agencies, including the USDA Natural Resource Conservation Service (formerly the Soil Conservation Service), the BLM, the Fish and Wildlife Service, the Department of Commerce's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Minnesota and Michigan Departments of Natural Resources (Bailey 1987b; USDA Forest Service 1993a). Much of the basic work was developed during the 1970's. Bailey's ecosystem classification approach to meet the needs of the Intermountain Region was national in scope from the very beginning.

Timber Management

As the 1970's began, national forest managers became increasingly aware of needed changes in national forest timber harvesting and management to meet wilderness and recreation uses, environmental objectives, and timber harvest targets. Such needs called for the fuller use of timber and better land management. They included constructing minimum-impact roads that were better fitted to forest uses and environmental needs; using new and advanced logging methods in environmentally sensitive areas; expanding investment in intensive forest practices; using more successful and effective regeneration methods; planning and designing timber harvest units more carefully to meet landscape objectives; using downed timber more fully, and reducing slash; using environmentally sensitive slash disposal methods; and much more (Roth and Williams 1986a).

The findings of the Monongahela, Bitterroot, and Wyoming clearcutting studies, and the Forest Service's national evaluation of National Forest Management in a Quality Environment: Timber Productivity highlighted this need for change. Subsequent congressional hearings on clearcutting and court suits challenging clearcutting reinforced it. Further evidence surfaced in many other studies undertaken by national forest managers at all levels on clearcutting, regeneration success, timberland suitability, the adequacy of timber harvesting systems, logging methods, and road layouts and designs to meet nontimber forest uses and environmental protection needs; determining allowable cut levels; writing and revising timber sale contracts to increase environmental protection; and other aspects of timber harvesting and management.

Three National Forest System-wide actions were undertaken in 1972 and 1975 to improve timber harvesting and management on the ground: implementation of The Action Plan for National Forests in a Quality Environment, stratification of the commercial forest land (CFL) base, and shifting the planning approach to unit planning. The first action gave forest-wide direction for applying recommended on-the-ground solutions to the 30 problem situations outlined in the "National Forest Management in a Quality Environment" report. The second action implemented the findings from the study on "Stratification of Forest Land for Timber Management Planning on the Western National Forests" (Wikstrom 1971).

Stratification of the Commercial Forest Land Base

The 1971 stratification study was directed by the Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station and conducted by staff foresters from the six western regions. It evaluated the suitability and availability of the CFL base for growing tree crops on six national forests — one in each region. Taking careful account of soil and slope conditions, land productivity, and land use, major factors influencing suitability and availability, the study reduced the 4.2 million-acre CFL base by 22 percent to 3.2 million acres. An additional 13 percent of the remaining CFL was reported economically or technologically unavailable due to high operating costs, low product values, or terrain that was subject to high risks of erosion or environmental damage with current conventional logging methods (Wilkinson and Anderson 1985).

The stratification study concluded that the traditional differentiation of commercial and noncommercial national forest land had been oversimplified and inadequate for national forest planning — especially for timber management planning. The study recommended stratifying CFL into subclasses, including a "marginal utility" subclass for forestlands with problems of erosion, regeneration, or restocking on unstocked lands or that were otherwise economically and technologically unavailable. It also proposed that such areas be excluded from current cutting budgets to avoid overcutting the commercial timber growing base (Wilkinson and Anderson 1985). A May 1972 amendment to the Forest Service manual on timber management plans established a new classification system requiring CFL to be stratified into four components: standard, special, marginal, and unregulated and the use of the same calculation procedure to determine potential yields and allowable cuts for each.

The CFL standard component, the largest one, involved few or no adjustments to the calculated harvest for multiple-use objectives. The special component encompassed lands that had been zoned to protect waterways, riparian areas, travel ways, aesthetic areas, recreation areas, and other resources. Land within this component usually required specialized silvicultural prescriptions and modified harvesting methods. Light partial cuts, longer rotations, fewer or no thinnings, no cutting along streamsides, and other special practices usually reduced its programmed harvests. In some cases where special practices could be applied to meet multiple use objectives and environmental constraints, full yields could be realized (Newport 1973a).

In the marginal component, very little timber was sold or harvested. For example, in 1973 eight forests in the Northern, Southwest, and Pacific Northwest Regions with new timber plans had programmed an allowable cut of 51 million board feet per year for their marginal lands compared to a potential yield of 156 million board feet. Six of the eight forests had an allowable cut of zero for their marginal components compared to a potential yield of 92 million board feet per year (Newport 1973b; Wilkinson and Anderson 1985). The fourth, or unregulated, component included harvests from experimental forests, administrative sites, recreation sites, and tracts isolated from markets. Such areas were very limited.

The new classification system generally reduced the estimated allowable cut on the national forests. For the eight forests with new timber plans, the new allowable cut calculated for 1973 averaged 9 percent below that for January 1, 1972 (Newport 1973b). The reductions were almost entirely from lands withdrawn from CFL. Withdrawals were attributed to special component (multiple-use coordination) and marginal component (critical soil or slope, economic, and environmental problems). By 1977, national forest managers had classed more than a third of the CFL timber base as special or marginal (Wilkinson and Anderson 1985).

The Shift to the Unit Planning System

The third major action modifying timber management planning was the shift from multiple-use plans to unit plans. Each forest had up to 20 planning units, each made up of one or more drainage basins. In 1972, the planning objective for each national forest over the next 10 years became the preparation of an intensive land use plan for each of its units. Units where critical management decisions were to be made were given planning priority. This new system required timber management planners to follow the land allocations of the individual unit plans. In this approach, the areas that unit plans zoned for recreation, scenic landscape, travel influence, water influence, streamside, or critical soil also had to be classified as special or marginal in each forest's timber management plan. Unit plan allocations also reflected national and regional timber production goals — the first time that national forest planning policy required timber management planning and implementation to be explicitly coordinated with other multiple uses.

A May 1972 Forest Service manual amendment made another important revision for timber management plans — the whole national forest was to be the area base for allowable cut determinations rather than individual working circles. However, in most regions, regional office timber staffs continued to make the potential yield and allowable cut calculations. The forest timber staff provided data and information, advised on various aspects of allowable cut calculations, and wrote the final timber management plan (Newport 1973a).

The Nondeclining-Flow Policy and Its Measure: Potential Yield

With the help of computer technology and the Douglas-fir supply study in 1969 (USDA Forest Service 1969), national forest managers, for the first time, were able to simulate timber harvests, management, and growth, decade by decade, for several decades beyond the first rotation. Unexpectedly, the study results revealed that, under the existing management intensity, current national forest harvest levels could not be sustained after the old-growth inventories had been harvested in the Douglas-fir region of Washington, Oregon, and California. The study projected that, using existing management intensity, harvests would be reduced 45 percent after the first 100 years. The current harvest level could be sustained only if forests were more intensively managed (Wilkinson and Anderson 1985; Roth and Williams 1986b).

The findings shattered the traditional basis for determining sustainable harvest levels in western old-growth forests — estimating the annual allowable cut by dividing the total old-growth inventory by rotation age and adding the net annual growth of immature timber to it. As a result, national forests shifted the determination of allowable cuts to a nondeclining-flow policy based on the potential yields (or harvests) that second-growth forests could produce using existing timber management intensity. The western timber industry took strong exception, because this policy would immediately reduce the timber supply from western forests. The industry argued that such a policy would waste the old-growth timber inventories, which greatly exceeded the stocking levels for managed forests (Wilkinson and Anderson 1985).

Ultimately, a compromise based on intensified timber management avoided timber harvest reductions. This solution required the Administration and Congress to make a commitment to increase the second rotation's potential timber harvest volume by increasing the funding for current reforestation, thinning, timber stand improvement, and other intensive practices to accelerate the growth of young timber.

The influence of the expected increases in future timber growth and inventories (due to more intensive stand management) on the current allowable cuts was initially referred to as the "allowable cut effect" (ACE). It has since been renamed the "earned harvest effect" (EHE). However, there was no assurance that Congress and the Administration would sustain higher funding for more intensive timber management over time. Lack of this guarantee made the Forest Service cautious and reluctant to raise allowable cuts based on the EHE.

Nevertheless, the regional forester of the Pacific Northwest Region wanted to evaluate how the Douglas-fir Supply Study findings and methodology and the underlying implications of new computer technology and projection methods would influence planning and management activities and decisions in the region. He wanted to know the impacts on data, information, and skill requirements for planning allowable cut levels; on timber management practices and intensities for individual forests; and on potential second rotation yield calculations. He wanted to know what implications different mixes and levels of timber management practices or improvements in timber utilization standards would have on allowable cut decisions and future timber program planning and funding.

In the early 1970's, Washington State's Gifford Pinchot National Forest was chosen to pilot this evaluation. It had just updated its timber inventory, its 10-year timber management plan was due to be updated, and it was representative of other productive Douglas-fir forests in the Pacific Northwest. As the Washington Office became involved with the study and the questions it addressed, the study became a national pilot for responding to the Pacific Northwest Region's concerns.

The Gifford Pinchot study found that allowable cut determinations could no longer be made without related decisions about investments to intensify timber management and about the types and amounts of timber management practices that would produce the growth and inventories to sustain current harvest levels into the next rotation (Roth and Williams 1986a). In 1975, the Gifford Pinchot National Forest became the first national forest permitted to reflect the EHE in its allowable annual cut determinations. This action was based on Congress' commitment to provide annual funding needed to support the intensified management over the new timber plan's 10-year life (Wilkinson and Anderson 1985).

On the basis of anticipated funding and backed up by monitored annual performance, this new approach was extended to the entire National Forest System in the late 1970's. Timber management plans documented the acres and types of silvicultural treatments needed to sustain the selected allowable cut level. Annual monitoring of actual treatments and acres treated showed whether such treatments satisfied the 10-year timber management plans' planned treatment schedule. Where actual performance fell short, individual forests reduced their allowable cuts accordingly. If the performance followed the plan, the allowable cuts could be maintained. The Gifford Pinchot fulfilled its scheduled silvicultural treatments during the balance of the 1970's and to the end of its 10-year plan in 1984 (Roth and Williams 1986a).

In line with the Church Guidelines, the Forest Service recommended that the EHE be determined by relying on reforestation, thinnings, and stand improvements for which growth responses had been reasonably documented. Forest planners were discouraged from relying on other intensive practices, such as fertilization and irrigation, whose growth benefits were poorly documented or largely speculative for large parts of the country (Wilkinson and Anderson 1985). Funding for silvicultural examinations, reforestation, and timber stand improvement practices increased almost three times, from $50 million in 1968 to $147 million in 1979 (USDA Forest Service 1992a).

Silvicultural Practices

For silviculturists, the late 1960's and 1970's were a time of growing recognition of the need for more intensive silvicultural examination and management of the national forest timberlands. This was particularly true in the West, where timber management had focused heavily on protection, access development, harvest area dispersal, and natural regeneration. Often the key foresters in the western regions were the timber sale planners and supervisors who carried the principal production workload and produced the major revenues within the National Forest System. Generally, the less-experienced foresters and forestry technicians at the district level were assigned the regeneration and related silvicultural responsibilities (Roth and Williams 1986b). In the East, where national forests were made up largely of heavily cutover timberlands, timber management had focused more heavily on rehabilitating cutover stands, improving their growth and growing conditions, regenerating unstocked lands, and rebuilding growing stocks. This naturally called for more attention to silvicultural examinations, their diagnoses, and the development of silvicultural prescriptions to guide actual management practices.

Both in the East and in the West, national forest managers increasingly recognized the need for more effective silvicultural treatments, including coordination with other multiple uses. This was well evidenced during the Church hearings in 1971. But each region did much more to evaluate its own stand conditions and management needs. In 1974, for example, an evaluation of the timber situation in the Rocky Mountain national forests found that only a third of the harvested land was regenerating successfully. The research bulletin that reported this study characterized the reforestation failures as "galloping devastation" (USDA Forest Service 1974a).

An analysis of the performance of sanitation silvicultural practices in the old-growth ponderosa pine stands in eastern Washington and Oregon revealed that sanitation was not developing any young stands. Sanitation harvests removed old-growth ponderosa pine trees that were being attacked or were highly susceptible to attacks by bark beetles. Sanitation harvests usually removed about 40 percent of the stand volume, leaving 60 percent to grow. They were seen by the average person as selection cutting. But sanitation harvests were not providing the regeneration needed for the next rotation. The heavy emphasis on sanitation-salvage cutting often left residual stands inadequately stocked and frequently with decreased, damaged, and poorer quality regeneration (Burke 1985). The new silviculture called for complete harvesting of the sanitized stands to start new stands (Roth and Williams 1986a). The Pacific Southwest Region made similar discoveries in California.

In the Pacific Northwest, the most basic finding was that its national forests were not regenerating within 5 years after timber harvest — an NFMA requirement. The record "was not good." Part of the solution was retraining key forest staff. Many foresters returned to universities for a semester or more of retraining to bring them up to speed in silviculture (Roth and Williams 1986a).

Following Chief's Office direction, the first national forest program for training and certifying silviculturists was established in 1973 in the Northern Region, where the Bitterroot National Forest had been a focal point of the Church hearings. It was entitled Continuing Education in Forest Ecology and Silviculture (CEFES). The program recognized the larger context of ecosystems, but due to the narrow understanding and limited ecological science and knowledge at the time, its primary focus was largely on the stand and individual tree interactions and processes with the local environment. Several aspects of other resource interactions were included in the curriculum but not fully integrated into a broader ecosystem context.

Other regions followed with programs of their own over the next 5 years. Each regional program was approximately equivalent to a masters degree and constituted one requirement for silvicultural certification. The other requirements usually included 3 years of silvicultural field work and the successful defense of a silvicultural prescription before a panel of experts. The continuing education programs in forest ecology and silviculture were strongly coordinated with university programs and faculty and other resource management agencies. In the Northern Region, 461 natural resource professionals participated in the CEFES program. Half of that number were Northern Region foresters or resource experts.

As silvicultural and forest ecology training programs were getting underway in 1973, national forest managers also began to intensify on-the-ground silvicultural examinations and evaluations. Qualified certified silviculturists became responsible for determining stand conditions and the need for cultural treatments. The level of effort for such examinations rose from 101 FTE's in 1968 to 188 person-years in 1975, when each person was examining about 25,000 acres per year. By 1979, FTE's rose to 836 person-years, with one person examining an average of 11,000 acres per year.

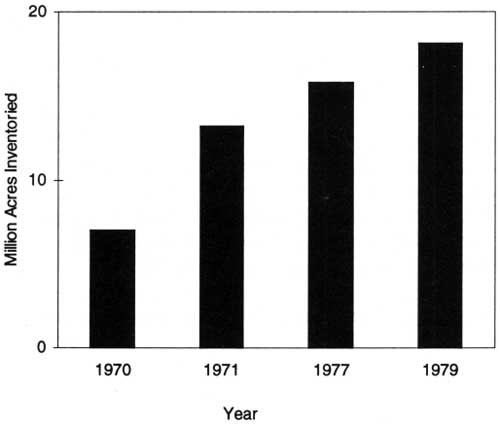

Congressional emphasis on eliminating the reforestation backlog gave a big boost to silvicultural examinations. In 1976 and earlier years, less than 5 million acres were examined. This quickly rose to nearly 9 million acres per year by 1979. The goal of the silvicultural examination and diagnosis program was to provide site-specific silvicultural prescriptions prepared or approved by certified silviculturists for all forested lands needing treatment. Each stand was to be reexamined every 10 years to update its silvicultural prescriptions and to keep pace with changing forest conditions and management needs and new technology (USDA Forest Service 1979, 1980, 1992a).

During the same period, almost every region developed automated stand recordkeeping systems to maintain long-term stand condition and management records — making reporting silvicultural accomplishments easier and more reliable.

Most timber activities, including reforestation, timber stand improvement, and timber sale preparation were based on silvicultural prescriptions derived from stand examinations. In areas planned for timber harvests, such examinations and diagnoses reviewed stand conditions throughout the entire sale area, identifying stands that would benefit most from planned harvest and those that would benefit from such treatments as thinning (Murphy 1994). Silvicultural examinations also produced the data and prescriptions needed for the intensified unit planning process that emerged in the 1970's (USDA Forest Service 1980).

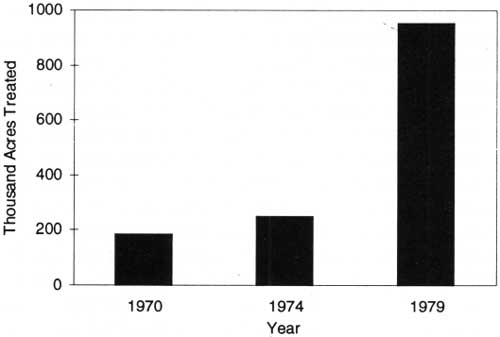

During 1978 and 1979, the silvicultural examination effort completed an NFMA-required inventory of all national forest lands in need of reforestation or thinning. This inventory included an estimate of the acres of treatment and the funds needed to eliminate the accumulated reforestation and timber stand improvement (TSI) backlog and to provide follow-up treatments on stands that would be harvested during the 8 years Congress had given the Forest Service to eliminate the backlog. As of October 1979, national forest lands needing of reforestation totaled 1.6 million acres; 882,000 were the result of timber harvest, fire, insects, disease, wind, and storms or failure of seeding, planting, or natural regeneration before 1975. The balance, 757,000 acres, was acreage that accrued after 1975. For TSI, generally precommercial thinning, the backlog was 2.2 million acres. Precommercial thinnings were needed to reduce the number of trees per acre and thereby increase overall stand health and individual tree growth. Thinning improved the health of stands by strengthening their resistance to drought, insects, disease, and other threats and increased the quality and value of their future growth. More than 400,000 acres of reforestation and 350,000 acres of TSI per year would be needed to eliminate the backlog (USDA Forest Service 1980).

The total acres reforested annually during the 1970's rose about 40 percent, from 313,000 acres in 1970 to 446,000 in 1979. Eighty percent were planted or seeded, while the remaining 20 percent were regenerated naturally. Twenty percent of the increase in regeneration treatments occurred between 1970 and 1977. The balance, 80 percent, was achieved in 1978 and 1979 in response to the newly developed inventory of backlog reforestation needs (USDA Forest Service 1972-1980).

TSI treatments during the 1970's rose almost 60 percent, from 303,000 acres in 1970 to 477,000 in 1979. TSI practices included thinnings and various other stand improvement measures such as fertilization, which was introduced in the early 1970's, and rose to more than 20,000 acres per year by 1976 (USDA Forest Service 1972-1980).

National forests continued to develop seed orchards and production areas to produce genetically improved for tree nurseries. The capacity of national forest seed extractories was increased as the production and collection of seeds increased. In 1970, for example, national forest seed extractories processed 22,000 pounds of seed. By 1979, they were processing 81,000 pounds. In 1976, the Forest Service initiated a major study of national forest nurseries to find out whether their existing capacity was capable of meeting the reforestation backlog of seedling needs and the needs resulting from new NFMA requirements. As a result of this study, two nurseries were added — one in the Southwest Region and the other in the Pacific Northwest.

Nursery tree production at the 13 national forest nurseries rose from 97 million trees in 1970 to 127 million in 1979. To increase planting stock survival rates on difficult reforestation sites, the nurseries also began producing containerized nursery stock. In 1979, they were providing more than 6 million containerized seedlings (USDA Forest Service 1972-1980).

The Forest Service developed standard methods for evaluating and certifying the effectiveness of silvicultural treatments in 1977 and implemented them in 1978. Regeneration could be certified successful after the third year for plantings and seedings and after the fifth year for natural regeneration. Failures, due primarily to insufficient tree survival, were recorded. Failures that needed further reforestation became a part of the reforestation backlog. TSI was certified in the first and third years after treatment. In 1979, national forests reported certified successful regeneration on 308,000 acres and certified success on 350,000 of TSI (USDA Forest Service 1978-1980).

In the 1970's, the intensification of silvicultural examinations increased the number and quality of silvicultural practices applied on the ground, improved tree and stand growth, and offset some of the impact of the nondeclining-flow policy on allowable cuts. The intensified silvicultural approach also reduced clearcutting, which had reached a peak of 564,000 acres in 1970 when timber was harvested from more than 1.5 million acres (Cliff 1971b). In 1978, as the timber harvest area rose to more than 2.6 million acres, the actual area clearcut was reduced to 310,000 acres — a 45-percent reduction in clearcut acres in 8 years (Forest Service 1992b).

Coordination of silvicultural examinations, planning, and treatments with other resource specialists likewise improved. But much of the coordination tended to be consultative and multidisciplinary rather than truly interdisciplinary. Although the NEPA environmental coordination precepts were available, national forests as a whole did not fully and mutually integrate resource specialists into the dominant timber management and harvesting tasks, which largely remained in the hands of the traditional timber staff. Thus, during the 1970's, a true, mutually interdisciplinary approach to timber and general resource planning and decisionmaking evolved slowly and in relatively few places (Roth and Williams 1986c).

Timber Harvests, Logging Systems, and Landscape Management

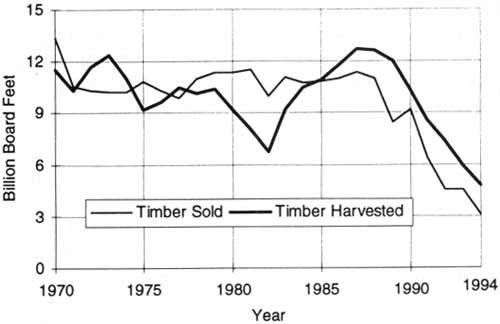

During the 1970's, the annual amount of national forest timber sold and harvested averaged about 11 bbf — about the same as for the 1960's (fig. 15). The average annual harvests, however, dropped from 11.4 bbf in the first half of the 1970's to 10.6 bbf in the second half. This reflected the decline of national housing and timber demands after the early 1970's (see fig. 10, chapter 4). The average annual volume of timber sold in this period was 0.5 bbf below the average annual volume sold and harvested in the last half of the 1960's (see fig. 6, chapter 3). This reduction largely reflected the influence of growing environmental pressures and the increased designation of wilderness.

|

| Figure 15. National forest timber sold and harvested, 1970-1994. Source: USDA Forest Service. |

During this period, the full annual harvests were concentrated on about two-thirds of the timber land base that was accessible and available for harvesting. This was due to the withholding of RARE I and RARE II roadless areas from harvesting in the absence of a final EIS evaluation of their suitability for wilderness. Because the Forest Service believed that RARE, then RARE II, would resolve the wilderness/roadless area issue in a few years, it kept the timber inventory in roadless areas in the CFL timber base and continued to sell and harvest the full allowable cut. From this viewpoint, it did not seem reasonable to cut back the annual allowable cut, close local mills, and cause unemployment for a relative short-term period. As a result, timber harvesting in already roaded areas was greatly accelerated throughout the 1970's, and this exacerbated environmental issues and concerns related to clearcutting.

This concentration of harvests began to cumulate pressures on related resources of forested rangeland, landscapes, and wildlife cover. Soil movement and stream sedimentation risks increased as larger-than-planned harvest areas had to be roaded and regenerated in the same watersheds. Mitigation efforts increased logging costs as more expensive logging methods and land treatments were required to protect other resources. The harvest concentration also contributed more to the public concern over national forest management than would have been experienced under the normally more dispersed timber harvest program (Roth and Williams 1986d). Throughout the 1970's, appeals and court actions became costly major obstacles to achieving the congressionally established and funded timber targets (USDA Forest Service 1979).

Logging Equipment: Methods and Systems

During the late 1960's, the need to improve logging equipment and systems to respond to the expanding environmental policies and standards and growing public concerns became increasingly clear throughout the National Forest System. Special harvesting methods without the environmental damage associated with ground yarding and road construction were needed to sustain national forest timber supplies (Newport 1973a).

The timber industry and loggers would require considerable persuasion and training to adopt new equipment and methods for felling and yarding timber. They had no independent incentive to make such changes unless such stipulations were built into the timber sale contracts. The timber industry and the loggers generally had only two basic logging systems: tractor yarding and high-lead (yarding with one end of the log on the ground). The high-lead system was largely used on national forests in western Washington and Oregon and northern California — an area where half of the total annual national forest timber harvest was concentrated. The Forest Service conducted special training programs for industrial, Federal, and State forestry personnel in California, Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Montana to promote advanced cable and tractor logging systems that national forest managers, engineers, and resource specialists had determined would reduce timber harvesting's adverse impacts on soil and water (Roth and Williams 1986a; USDA Forest Service 1972).

The Pacific Northwest Region was the leader and innovator in new logging equipment and systems and fuller utilization of the timber sold, but this was also shared by other regions. It introduced the yarding of unutilized material (YUM yarding), which cleaned up many sale areas, made them easier to reforest, and added to timber supplies. During the 1970's and earlier, logging residues were generally considered cull material. They were widely scattered over each cutting unit or piled and usually burned. YUM yarding concentrated this material at a central landing point. The small material was difficult to sell, but, periodically, when the pulp market was strong or pulp mills experienced a wood shortage, many of the YUM piles were sold for pulp production. Others were taken for domestic fuelwood (Roth and Williams 1986a).

Other practices applied in the Pacific Northwest Region and elsewhere included requiring loggers to remove lower diameter materials from the sale area. As an incentive for purchasers, the smaller, less merchantable timber sale components were offered at a fixed lump-sum contract price per acre (Roth and Williams 1986a). Salvage logging was introduced to increase timber supplies and to reduce the loss of such timber to decay and insects. In 1977, Congress established a revolving timber salvage sale fund. By 1979, such sales added a billion board feet annually to national forest sale volumes. During the 1970's, the amount salvaged grew as timber markets and prices became stronger and receded in years when markets were weaker. The trend in the use of small timber materials followed a similar pattern (USDA Forest Service 1980; USDA Forest Service 1992a). National forests also instituted a free use-permit system so that people could cut dead timber for fuelwood. Before 1970, the use of national forest timber for home-heating fuelwood was nominal. By 1979, however, some 700,000 families were collecting a total of 3.2 million cords per year of national forest fuelwood — a trend that continues today (USDA Forest Service 1980). Directional felling of old-growth was introduced by the Pacific Northwest Region as a contract requirement to reduce tree breakage, improve tree utilization, and reduce erosion damage on steep slopes with shallow soils (Roth and Williams 1986a).

Perhaps the Pacific Northwest Region's most significant accomplishment toward better land management was the development, improvement, and diversification of entire logging systems and fitting them to the site-specific needs of individual harvest areas. The Pacific Northwest Region initiated a program for testing and demonstrating various forms of skyline logging (a system that lifts both ends of logs off the ground during yarding). Helicopter and balloon logging methods were also tested. Helicopter yarding proved to be very costly ($1,300 per hour of flight time) and ultimately was limited to areas where other logging systems could not be used on the timber sale and the environmental benefits and road-cost savings justified the costs.

|

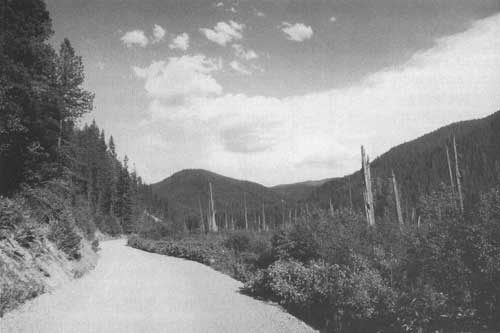

| The typical logging road on Alaska's Tongass National Forest is also used for recreational fishing and hunting. (USDA Forest Service Photo. Taken by W.S. Cline) |

Most logging improvement focused on skyline logging systems that could operate on concave slopes and reach out laterally for 800- to 5,000-foot yarding distances. A Pacific Northwest Region survey of lands requiring such systems estimated that they contained a 40-bbf timber inventory — equivalent to an annual allowable cut of 0.4 to 0.5 bbf over 100 years (Roth and Williams 1986a; Newport 1973b).

The skyline logging development program offered several practical challenges. National forest engineers were basically trained as civil, not logging, engineers. Forestry schools' logging engineering programs had been greatly retrenched or eliminated. Thus, there was a major challenge to recruit and/or train logging engineers who could test, evaluate, and demonstrate advanced logging systems. These logging systems needed to be evaluated on both environmental and economic criteria to ensure that they would be successfully adopted on national forests by the timber industry. A third challenge was to develop and provide training programs for technicians on how to use the advanced logging systems and for line and staff officers on how to design timber contract specifications for using these advanced logging systems. During the 1970's and later, the Forest Engineering Institute (FEI) at Oregon State University met these challenges. It provided a month-long course for technicians and a 1- or 2-year training program for professional foresters and engineers. A research and development program to improve existing and develop advanced logging systems called FALCON (Forestry, Advanced Logging, and Conservation) was proposed and funded from existing national forest appropriations for a 5-year period. FALCON's second component was to study the compatibility of different logging systems with various resources and their impact on those resources. A third component established a demonstration area in the Pansy Creek drainage on Oregon's Mount Hood National Forest where a person could observe all the different logging systems and their impacts on the resources of a harvested area and its surrounding sites (Roth and Williams 1986a).

Road Design and Construction

The Pacific Northwest Region modified road designs and construction to reduce their impact on soil and water resources — particularly where roads served individual harvest settings and otherwise carried light traffic volumes. Civil engineers managed the national forest road program and set road design standards. The Forest Service began to use civil engineers in the early 1950's when national forest logging and road construction began to expand rapidly. Prior to that time, forest engineers were primarily forestry school logging engineering graduates.

Civil engineers were trained primarily to meet urban and highway engineering standards and the roads that they designed for lower class forest roads often exceeded the standards needed or required for forest use and management. These roads were generally too wide and were built to too high a standard. They involved larger volumes of sidecast rocks and soils than necessary to maintain their grades and widths. Excess material was often pushed over roadsides, where it became an erosion and sedimentation problem.

This problem was familiar to and a concern of national forest managers throughout the system, but it took Regional Forester Rex Ressler's leadership to bring this situation to a head in Washington and Oregon. A region-wide forest supervisor s meeting — an historic first for such meetings — was held on a timber sale road where alternative road standards could be thoroughly reviewed and discussed in relation to actual ground conditions and environmental needs. The meeting's outcome was clear direction from the regional forester to design and build what came to be known as "minimum-impact roads." Minimum-impact roads were narrower, had less sidecast material, and required less end hauling. They required no special surfacing material and less rock. Compared to the impact of the previous higher standard road designs, they substantially reduced the scarring of hillside landscapes. Minimum-impact roads were increasingly used in the Pacific Northwest Region during the 1970's, and their use continues today. Similar road design and construction improvements were made in other regions (Roth and Williams 1986a).

During the 1970's, almost 75,000 net miles were added to the national forest road system (fig. 16). Road construction and reconstruction (rebuilding existing roads that had been degraded or did not meet existing design standards or reopening closed roads) averaged 9,494 miles per year for the decade. (USDA Forest Service 1972-1980). Most of the reconstruction was concentrated in the regions with the largest timber harvest volumes. In the Pacific Northwest Region, for example, which harvested more than 42 percent of the total national forest timber cut during the 1970's, reconstruction constituted almost half of the total road construction (Coghlan 1995). Reconstruction of existing roads to current requirements and standards did not count as net additional road mileage. Roads actually constructed and reconstructed in the 1970's totaled 94,944 miles, more than the net increase in the total miles of national forest roads. Only 6.4 percent, or 6,013 miles, of these roads were funded by direct congressional appropriations. The vast majority were built by timber operators and funded by timber sale proceeds (purchaser credit). Purchaser-built roads were primarily logging spur roads and some secondary or collector roads. Mainline access roads were usually funded with appropriated funds and often included standards necessary to meet recreation traffic requirements as well as mainline road needs for loggers to reach public highways.

|

| Figure 16. Total road mileage in the National Forest System, 1967-1995. Source: USDA Forest service 1996. Data provided by Washington Office Engineering. |

Landscape Management

In the late 1960's, national forest managers recognized that sustaining timber harvests would require blending the location and design of timber harvest areas and roads with the general landscape in ways that protected visual quality. This need led to a new landscape management approach that provided a harvest layout design that responded to the public's interest in landscape views and vistas while achieving timber harvest objectives (USDA Forest Service 1972, 1974).

|

| Moon Pass Road, Idaho Panhandle National Forest, where it passes cedar swamp snags and forest regrowth from the 1910 fire. This gravel-surfaced road is cooperatively maintained by the Forest Service and Shoshone County, mainly for recreation in the summer and snowmobiling in the winter. (USDA Forest Service Photo.) |

While the first efforts to integrate harvest locations and boundaries with the natural landscape emerged in California, systematic visual resource management guidelines emerged in Oregon and Washington. At the Chief's request, a silviculturist and landscape architect combined their skills to prepare a regional guide as the first component of a national manual released in 1974 under the title National Forest Landscape Management (USDA Forest Service 1974b; Roth and Williams 1986a). This manual identified visual landscape characteristics and provided guidelines to analyze the visual effects of different timber harvest alternatives. Its main purpose was to help national forest managers coordinate timber harvest designs and plans with maintaining acceptable vistas. Such landscape management involved both the location and shaping of timber harvest units. During the 1970's, national forest managers recruited the Nation's, and perhaps the world's, largest staff of landscape and environmental experts to plan timber harvest area landscapes. Such specialists became skilled in harmonizing national forest installations such as roads, log landings, ski lifts, and other signs of land management with nature's woods and natural beauty.

Chapters on range and roads were added to the National Forest Landscape Management series in 1977. These handbooks provided vocabulary, planning guidelines, and an objective-setting process. The range chapter offered ideas on acceptable manipulation of forage vegetation and the installation of range improvement structures. The roads chapter provided methods to reduce the visual impact of roads so that they "lay lightly upon the land" (USDA Forest Service 1978). A supplemental report, "Land Use Planning Simulation," described how the visual impacts of proposed timber sale areas, power lines, surface mining, and other land uses and installations could be evaluated by projecting visual impacts on a screen. This became a useful tool in providing large groups of people the opportunity to see and react to the visual effects of various timber harvest alternatives. In 1978 and 1979, additional chapters on timber and wildlife were prepared. They illustrated methods for combining visual resource management with silvicultural and wildlife habitat practices to achieve attractive as well as productive landscapes.

The use of the National Forest Landscape Management Handbook broadened beyond national forests as demands for the publication and its concepts from universities, other Government agencies, and the public grew throughout the 1970's (USDA Forest Service 1978-80). To reflect the substantial advances in research and technology since 1974 and respond to a significant increase in the demand for high-quality scenery, the 1974 handbook was revised and updated and released in August 1996 under the new title Landscape Aesthetics: A Handbook for Scenery Management.

By 1979, all national forest regions had completed analysis and mapping of that 40 percent of National Forest System lands where visual quality objectives needed to be integrated with forest management activities. This helped to ensure that the scenic aspects of such land areas would taken into account as growing national forest land use and management shaped their future direction.

Wilderness Management and Use

Much of the wilderness management effort in the 1970's was devoted to wilderness planning for RARE I and RARE II and evaluating the 5.5 million acres in 34 national forest primitive areas that Congress had assigned for further study in the Wilderness Act of 1964. National forest primitive area evaluations were completed on schedule. By September 1974, all 34 areas had been recommended to Congress for designation and had actually been designated as wilderness. In the same year, the national forests celebrated the 50th anniversary of the designation of the first administrative wilderness in the Nation — the Gila Wilderness — with commemorative ceremonies held in Silver City, New Mexico. The celebration was held within sight of that first wilderness established on national forest lands.

The expanding number, area, and use of national forest wildernesses increased the wilderness management challenge in every dimension in the 1970's. Their number rose by 80 percent, from 61 to 110. Their area increased from 9.9 million acres to 15.3 million (55 percent). Their dispersion among the States rose from 13 in 1970 — 10 in the Far West plus Minnesota, New Hampshire, and North Carolina — to 26 States in 1979. Twelve of the new States were in the East, a reflection of the eastern wilderness legislation: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Missouri, South Carolina, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. Utah was the thirteenth. But, even with this wider dispersion of wilderness areas, some 92 percent of the total designated wilderness remained concentrated in the eight Rocky Mountain States and the three Pacific Coast States (USDI/USDA 1970-1980).

The growing number and expanse of designated wilderness areas multiplied the need for wilderness management plans. By 1979, management plans had been completed and implemented for 46 areas. Planning was under way for another 38 and pending for most of the 24 units added in 1978. No areas were added in 1979. The new national forest land and resource management planning guidelines issued in 1979 fully integrated designated wilderness management direction into the new forest plans.

A 1970 study, prepared by the Department of the Interior in consultation with national forest mining specialists updating the 1961 and 1964 reports to Congress on wilderness mining activities, reported 18,000 unpatented mining claims and 1,500 patented claims in designated wilderness and primitive areas. In the 1964 Wilderness Act, Congress had directed that these mineralized areas, located on 34 national forests, be evaluated and that recommendations be made on their suitability for wilderness. The mineral reviews for these areas were completed and published in 1973 by the U.S. Geological Survey and Bureau of Mines (USDI/USDA 1970-1980).

The most demanding challenge facing national forest wilderness managers in 1970 was the preservation of the wilderness resource and its pristine conditions in the face of rapidly rising use, which in that year exceeded 5 million RVD's. The management experience to 1970 also clearly demonstrated a rising trend of wilderness use violations; these exceeded 200 per year and involved 173 prosecutions. Many violations were unintentional, where violators generally failed to comply with Forest Service regulations. Many users were either unaware that they had entered wilderness areas or were uninformed about wilderness restrictions — indicating a priority for wilderness user education and clearly marked wilderness boundaries (USDI/USDA 1970-1980).

National forest managers were participating and assisting wilderness search and rescue operations, which were likewise increasing. In 1971, for example, there were 84. A rising number of fatalities were also being reported each year. In 1971, there were 16 — four lives were lost in airplane accidents and 12 fatalities occurred as people were testing their skills against the wilderness. Many more people suffered serious injuries during their wilderness activities. Such instances were expected to occur more often as the number of wildernesses and users continued to grow.

A more systematic problem was occurring at the most popular lakes, streams, and other scenic or attractive spots in the wildernesses, particularly those near highly populated urban areas or in areas that were otherwise readily accessible. Many groups and individuals visiting such attractions were not seeking, or often did not have the skills to meet, the challenges wilderness offered. The intensity of use around many such spots was rising to the point that it was threatening the quality of the wilderness resource. Thus, in the early 1970's, the following wilderness management priorities emerged: preparing and distributing educational information on wilderness restrictions, ethics, and safety to users; posting wilderness boundaries; establishing proper people-carrying capacities for wilderness and managing use accordingly; cleaning up human debris and waste; providing sanitation controls; removing nonconforming structures and developments; and administering grazing and mineral exploration activities as permitted by the Wilderness Act.

To serve the preferences of national forest visitors seeking primitive-type offroad activities without the need to do so in a formally designated wilderness, national forest managers expanded complementary space and sites outside the wilderness for back-country hiking, camping, hunting, fishing, and other roadless recreation activities.

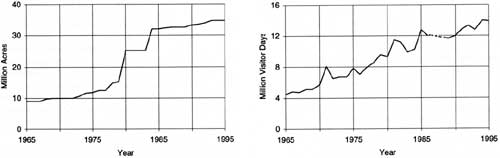

During the 1970's, the number of wilderness visitor days rose by 85 percent. This compares with a 27-percent increase in the total acreage of national forest wilderness and primitive areas available for wilderness experience and activity (fig. 17). The available area rose from 14.3 million acres in 1968 to 18.1 million in 1979. Thus, the intensity of use of wilderness opportunities nearly doubled in the 1970's. This rapid growth in wilderness use contrasts with a 35-percent increase in total outdoor RVD use on national forests during the same period.

|

| Figure 17. National forest wilderness area and visitor use, 1965-1994. Source: USDA Forest Service. |

On a State-wide basis, California, with 13 percent of total available national forest wilderness and primitive area in 1979, continued to receive the most RVD use — about 20 percent of the total. The Boundary Waters Canoe Area in Minnesota, with 5 percent of the available wilderness and primitive area, however, was the single most intensively used wilderness. It provided 12 percent of the total national forest wilderness visitor day use. Together, the California wildernesses and Boundary Waters Canoe Area accounted for almost a third of national forest wilderness use.

|

| Fifty-four wilderness hikers crossing Bear Prairie on the annual "Gates of the Mountains" wilderness hike, Helena National Forest, Montana, 1970. (Forest Service Photo Collection, National Agricultural Library. Taken by Philip G. Schlamp.) |

To manage wilderness use consistent with its capacity and capability, national forest managers introduced a wilderness permit system in the early 1970's. They expanded its use wherever it would help to ensure that wilderness resources would be properly and safely used and would help to control human debris and waste. By 1979, 50 percent of wildernesses and primitive areas, including all California wildernesses and the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, were under the permit system. Where it was implemented, the permit system generally worked satisfactorily and improved wilderness management effectiveness. Permit issuance, either by a staff person or volunteer at a wilderness trailhead or at the local ranger district office, gave national forest employees the opportunity to communicate directly with wilderness users and inform them about wilderness care and use. Wilderness users appreciated and responded to this information. Where permits were used, national forest managers reported less litter and reduced ecological impacts (USDI/USDA 1970-1980). Individuals, groups, and organizations who were interested in maintaining a high-quality national forest wilderness system increasingly volunteered work on projects. They communicated with visitors, performed searches and rescues, maintained signs and trails, cleaned up campsites, removed debris, and performed various other supporting functions.

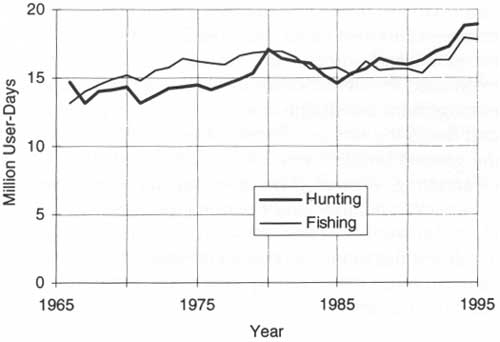

The dominant recreation activities among wilderness users in the 1970's were hiking; horseback riding with pack stock and backpacking, usually with guide services; camping; hunting; fishing; and mountain climbing. In the late 1970's, winter wilderness activities were becoming more popular in some places and were seen as likely to increase the need for search and rescue operations, which were ranging between 265 and 310 per year. In the late 1970's, fatalities averaged more than 40 per year. Many could have been prevented with better understanding about how to meet nature on its terms, how to effectively prepare for emergencies, and how to develop skills in wilderness activities and conditions.

Trespass and violations increased during the 1970's despite the improved intensity of wilderness information, supervision, and management. In 1976, they reached a peak of 794 and remained a continuing problem for the balance of the decade. Wilderness violations involved various forms of motorized equipment, occupying and using wilderness without a permit, not complying with a wilderness permit, and violating special wilderness restrictions. In 1978, two incidents of armed robbery and one murder required coordination with local law enforcement authorities (USDA/USDI 1970-1980).

Although wilderness interests were successful in getting Congress to endorse lower than pristine standards for wilderness candidate areas and wilderness designation, the management of national forest wilderness continued to be guided by pristine standards. Wilderness interests did not oppose them — although some users complained about permitted livestock grazing and horse use, legitimate mining activities, thefts, low-flying aircraft, and, in some places, the permit system.

Outdoor Recreation Use and Management

RVD use for a wide variety of recreation activities grew throughout the decade, despite rising concerns and issues among various resource interest groups and some users about wilderness preservation, timber harvest levels and related road construction, and clearcutting, all of which probably contributed to the culmination of the wilderness preservation, timber harvesting, and clearcutting issues during the 1970's. National forest management of multiple uses, on the other hand, encouraged and helped make this growth possible.

Growth in Total Visitor Use

National forest outdoor recreation use in the 1970's increased from 163 million RVD's in 1969 to 220 million in 1979 (see fig. 8, chapter 3). While annual RVD use on other Federal lands, mainly national parks, declined after 1976 by nearly 30 million RVD's, outdoor recreation use on national forests continued to rise by more than 20 million RVD's. Fitting these expanding demands for outdoor recreation opportunities with other uses on national forests became and remained a major management challenge for national forest managers throughout the decade (USDA Forest Service 1970-1980).

Visitor use and growth were concentrated in the western national forests. The seven western national forest regions accounted for 78 percent of the RVD use and more than 80 percent of the RVD growth during the 1970's. The western regions included the Pacific Coast and Rocky Mountain States plus Alaska, North and South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas. They made up barely 20 percent of the U.S. population, but had more than 90 percent of the national forest area. Visitor use was largely local or regional and averaged 3.5 RVD's for each western person each year. The intensity of use varied by State from 2 to 3 RVD's per person per year in South Dakota and the most populous States of California and Washington to 10 to 12 RVD's per person per year in less populous States such as Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming. In North Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas, where national forest acreage was minimal, national forest use averaged barely a tenth of a visitor day per capita per year (Poudel 1986).

RVD use on national forests in the East totaled 36 million in 1969 and was about equally divided between the Southern Region and the Lake States and Northeastern Regions (combined and called the Eastern Region in mid-1970's). By 1979, it had risen by 32 percent, to 48 million. Almost 85 percent of the increase had occurred in the Southern Region. Because the population in the East is very dense and highly urbanized, average per capita use per State among the Eastern States was very low. Although national forest acreage in the East was small, and constituted less than 12 percent of the area of the National Forest System, it was used twice as intensively as that in the West (Poudel 1986).

Camping accounted for more than 23 percent of the increase in RVD use on all national forests. It rose by 13 million RVD's between 1969 and 1979. Motorized travel through and within national forests for general viewing and accessing specific recreation sites and opportunities accounted for 20 percent of the RVD increase, rising by 17 million during the decade to 50 million. Safe, drivable roads became important during the 1970's, not only for viewing the forest and its mountain scenes and environment, but also for accessing the wide variety of recreation resources — streams, lakes, mountainsides, and trails and the developed sites for camping, boating, swimming, skiing, and other activities (Poudel 1986).

Outdoor recreation visitors to national forests typically devoted about 38 percent of their RVD's to activities in developed sites such as campgrounds and picnic areas; winter sports sites; water developed for boating and swimming; observation sites; various interpretive, informational, and documentary facilities; fishing areas and trailheads; playgrounds, parks, and sports fields; recreation residences; and hotels, lodges, resorts, and concessions. Visitors devoted about 42 percent of their RVD's to dispersed recreation activities throughout the national forests and an additional 20 percent to motorized travel on forest roads (Poudel 1986).

Staffing for Recreation Management

National forest staffing for recreation planning and management and operations and maintenance generally followed the upward trend in RVD use. Professional and support services rose by 35 percent between 1973 and 1979, from 4,300 FTE person-years to 5,900 FTE's (USDA 1992a). Almost 95 percent of the staffing was directed to general recreation and served both developed and dispersed recreation sites, opportunities, and uses. This included landscape planning, which was a growing component of the recreation function during the 1970's and worked closely with timber sale planners and road engineers. The remaining 5 percent of the staffing was directed to cultural resources and wilderness management.

National forest managers also graciously and generously used human-resource programs and volunteers to accomplish a large part of their expanding operational, maintenance, and construction work needed to support rapidly growing recreation use and activities on national forests. The programs (shown with their dates of initiation on national forests) include the Job Corps (1965); the Youth Conservation Corps (1971); Volunteers in the National Forest (1973); the Senior Community Service Employment Program (1974); the Young Adult Conservation Corps (1977) and various hosted programs (1960's-1970's) of other agencies, States, and the private sector, such as College Work Study, the Work Incentive Program, Vocational Work Study, and programs authorized under the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act of 1973 (CETA).

These programs provided conservation education through natural resource activities on national forests, skills training, employment, and national service opportunities for the unemployed, underemployed, minorities, disadvantaged, youth, elderly, retired people, and persons with disabilities. Through conservation work projects, participants made valuable, increasing contributions to visitor information services, recreation site and facility maintenance, camp unit construction, trail maintenance and construction, and clerical support through out the 1970's. The total work provided by human resource programs and volunteers rose from less than 4,000 person-years in 1970 to more than 6,000 person-years in 1975, and more than 16,100 person-years in 1979. The great growth after 1975 was largely due to the initiation of the Young Adult Conservation Corps in 1977 and expansion of the Youth Conservation Corps and Senior Community Service Employment programs during the 1970's. The number of volunteers continued to expand rapidly after 1975 (USDA Forest Service 1972-1980).

In 1979, 93 percent of the total services available to the Forest Service from human-resource programs were used on national forests. Recreation resources and users received a major share. Other resources benefitting from these services were timber stands and wildlife habitats. The total estimated value of all human-resource services provided to the Forest Service in 1979 was $164 million and compared with $28 million in 1975 and about $13 million in 1970, measured in constant 1979 dollars (USDA Forest Service 1972-1980).

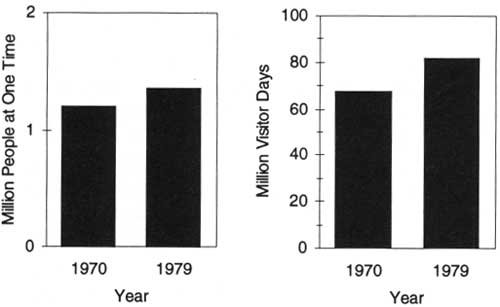

Capacity and Use at Developed Sites

In addition to upgrading the sanitary facilities at developed recreation sites, the annual recreation investment on national forests in the 1970's rehabilitated many deteriorating sites and constructed some new ones. Between 1970 and 1979, Federal and private investments increased the capacity of national forest developed recreation sites for visitor use occupancy by 12.6 percent. Use at developed sites rose by 21.0 percent during this same period, to 81.9 million RVD's — more than the capacity of developed sites could accommodate (fig. 18). Forty percent of this increased use was accommodated by more effective and intensive use of existing sites during the recreation season. Recreation visitors were encouraged to use available existing sites on weekdays rather than weekends. To achieve fuller use of the available developed sites, new sites or those replacing abandoned sites were located in areas of stronger recreation demand and greater user access (Poudel 1986).

|

| Figure 18. Developed outdoor recreation site capacity and use, 1970 and 1979. Source: USDA Forest Service. |

National forests operated 53 percent of the total occupancy potential at developed sites. The balance was privately operated, usually with privately constructed facilities, under the national forest special use permit system. The privately operated facilities included all recreation residences and public concession sites; most of the hotels, lodges, and resorts; some winter sports sites and boat marinas; and organizational camps administered by youth organizations and other groups. Privately operated developed-site occupancy capacity increased by 15 percent during the 1970's; national forest occupancy capacity increased by almost 10 percent (Poudel 1986).

The largest occupancy capacity increase occurred at winter sports sites, which grew by 43 percent during the 1970's. RVD use of winter sports sites, mainly ski areas and other facilities, increased by 6.4 million, or 98 percent. The next largest increase in RVD use occurred in campgrounds. It grew by 4.1 million RVD's, or 10 percent, and was accommodated primarily by more intensive use of existing sites. The use, however, shifted among campground sizes and types of camp units. Over the decade, a third of the campgrounds with 25 or less units were shut down and their capacity replaced by expansion of larger existing campgrounds and by constructing new, larger ones. Between them, campgrounds and winter sports sites accounted for 75 percent of the increased use at developed sites between 1970 and 1979. Boating sites and interpretive sites each accounted for an increase of 1.1 million RVD's of use and about 15 percent of the total increase. Occupancy capacity for each rose between 50 and 60 percent.

Visitor use of hotels, lodges, resorts, and public service concessions increased by 800,000 RVD's, or 17 percent, and was accommodated largely through increased use of existing facilities. On the other hand, recreational residence use declined by 900,000 RVD's as national forest managers reduced the number of recreation residence permits. Beginning in the late 1960's, national forest policy called for a shift in the use of isolated individual private recreation residence sites to public purposes. Where public values exceeded those for continued private use, existing permits for some of the more isolated residence sites would be canceled and no new permits would be issued for establishing any additional private recreational residences. Permits for recreation residences that were located in established residential tracts were not subject to cancellation (USDA Forest Service 1969, 1978-1980).

Other uses, such as swimming, picnicking, and scenic observation, also grew, between 400,000 and 450,000 RVD's, and were accommodated primarily through more effective use of existing sites. The number and capacity of picnic areas and scenic observation sites were reduced. Visitor use at existing playgrounds, parks, and sports sites quadrupled from 1970 to 1976 and led to expanding existing sites and building new sites that doubled occupancy capacity during that period. A further doubling of capacity by 1979, however, proved excessive and was not fully utilized until well into the 1980's (Poudel 1986).