|

Managing Multiple Uses on National Forests, 1905-1995 A 90-year Learning Experience and It Isn't Finished Yet |

|

Chapter 6

National Forest Management for Multiple Uses: 1980 to 1995

The General Setting

The new approach to national forest planning, the economic and policy highlights of the 1980 to 1995 period, the expanding role of public participation, and growing public confrontation are briefly described in this introductory section to provide an overview of the challenging environment for national forest planning and management during the 1980's and early 1990's. These topics are then developed in more detail in subsequent sections.

A New Approach to Forest Planning

NFMA's final implementing regulations, issued in 1979, initiated a new emphasis on integrated land and resource planning for multiple uses on national forests. The implementation of NFMA was as much a new learning experience as a new planning experience on each national forest, and during the 1980's it continually evolved and improved on each forest.

This new approach was linked with nationally determined long-term RPA goals and called for the integrated planning for all resource uses — recreation, fish and wildlife, water, timber, range, and wilderness — on a forest-wide basis for the next 50 years. This approach superseded and integrated the previous unit planning system, which had required 1,200 "unit" land use plans on 123 national forests, and the functional planning for individual resources that involved the periodic updating of 48 separate major resource plans on each forest. NFMA planning replaced these plans with regional planning guidelines for each of the nine national forest regions and forest-wide integrated land use and resource plans for each of the 123 national forests.

NFMA did not require regional guidelines, but they were considered a useful step for linking the national RPA program with individual forest plans. Regional guides allocated the long-term RPA goals among the forests and were intended and designed to ensure comprehensive and consistent national and regional management direction for all national forest resource uses (USDA Forest Service 1982a).

The goal of NFMA planning was to reinforce a more holistic approach to national forest resource planning, use, and management on a forest-by-forest basis. It was intended that all multiple uses receive equal consideration as long-term planning allocated them to national forest lands for future implementation and that multiple-use planning reflect both the needs and demands of the American people and the capability of national forest lands and resources to serve them. Guidelines for managing the multiple uses would be adequate to sustain the uses and maintain the productivity of the land and the soil. National forest planning under NFMA called for a more evenhanded balancing of resource uses with each other and with national forest land and resource capabilities — forcing greater attention to the interdependent and interactive relationships among the uses and the resources on a forest-wide scale (Cawley 1990). NFMA planning in this way was another step toward an ecosystem approach to planning and managing multiple uses on national forests.

The Forest Service formally considered a fully holistic or ecosystem approach to NFMA planning as it evolved strategies for implementing NFMA planning, but did not adopt the approach for several reasons. Federal policy attention within the Administration and in Congress throughout the 1970's had been strongly focused on increasing timber supplies to achieve housing goals and dampening timber product prices and general inflation. The Forest Service and key Federal policy officials were optimistic that national forest timber supplies could be further increased through greater investments in timber and other resources and appropriate management measures to avoid or mitigate any adverse environmental impacts. Some managers felt that they could adapt their watershed planning and range and wildlife management models to a holistic ecosystem approach for managing multiple uses. But these models and their databases were geared to answer timber suitability questions rather than questions about ecosystem management.

The data supporting timber planning were by far the best developed, with watershed next. The available data for other resources was piecemeal and generally insufficient. Such databases did not generally lend themselves to, and were not readily adaptable for, an ecosystem approach to planning. The models available for ecosystem planning, on the other hand, would have fragmented the timber database and reduced its effectiveness for timber resource planning and for resolving pressing timber supply questions. This was not acceptable. Addressing the timber supply issue was a high priority and required a traditional timber-oriented planning model — one that could readily evaluate the economic efficiency of timber management alternatives. This choice reflected the Forest Service's strong belief that once the timber supply issue was resolved, provisions for other resource uses would fall in line with NFMA resource and environmental standards and guidelines.

The Forest Service was anxious to respond promptly to the NFMA and NEPA planning guidelines. In 1979, for example, final forest plans and EIS's for all but two of the 123 national forests were tentatively scheduled for completion by the end of FY 1983 (USDA Forest Service 1980b). There was a lack of passion and readiness to try to transform the planning process on 123 national forests to a fully holistic ecosystem approach — although the concept did have appeal and was considered at the time. As it turned out, even with NFMA's limited shift toward an ecosystem approach, most of the plans were not finalized until after 1983, and a few not until the 1990's.

In 1982, USDA policy officials under the Reagan Administration undertook the revision of the 1979 NFMA regulations to better balance economic efficiency with environmental protection. They strengthened the role of economic criteria for NFMA planning and decisionmaking and rewrote proposed environmental guidelines to reflect the broader and more general direction of the NFMA legislation itself. Although the action was viewed in some circles as an effort "intended by the Reagan Administration to weaken NFMA as a statement of environmental policy," the final NFMA regulations of 1982 added language that "substantially strengthened" environmental protection for some resources (Caldwell et al. 1994). The most significant case in point was the new language added to elaborate the 1979 NFMA regulatory guideline "to maintain viable populations of all existing native vertebrate species in the planning area." The new language provided that:

A viable population shall be regarded as one which has the estimated numbers and distribution of reproductive individuals to insure its continued existence is well distributed ... to insure that viable populations will be maintained, habitat must be provided to support, at least, a minimum number of reproductive individuals and that habitat must be well distributed so that those individuals can interact with others.

This strengthened language was to play a major role in the resolution of the spotted owl controversy that was emerging in the 1980's on national forest lands in the Pacific Northwest and California (Caldwell et al. 1994).

Economic and Policy Highlights

Double-digit inflation and interest rates emerged in 1979 and 1980 and were accompanied by high rates of unemployment. In response to these conditions, the housing market in the early 1980's dropped sharply over the decade to about 1.7 million units per year, and then to an even lower level in the early 1990's. However, average annual softwood lumber and plywood use during the 1980's and early 1990's rose by more than 10 percent above the peak average annual use of the 1970's, due largely to increased remodeling and repair of existing housing.

Administration and congressional priorities for increasing timber supplies from national forests remained strong throughout the 1980's. In the early 1990's, however, this policy pressure abated as housing construction fell to an average of 1.4 million units and court suits were instrumental in reducing national forest timber harvests in the Pacific Northwest. Despite strong softwood lumber and plywood demands between 1980 and 1995, their relative prices remained substantially below the record price levels of the 1970's. This was largely due to an increase in timber supply — a 60-percent increase in softwood lumber imports from Canada and a 40-percent expansion in softwood lumber and plywood production from the southern pine forests (Ulrich 1990; U.S. Bureau of the Census 1993a, 1993b; Warren 1995; Council of Economic Advisors 1994).

The high inflation and high interest rates in 1979 and 1980 also brought severe pressures to reduce Federal spending and budgets. In 1982, under the Reagan Administration, general inflation and interest rates were controlled and reduced, but Federal budget deficits expanded dramatically during the balance of the 1980's and early 1990's — continuing the pressure to control and reduce Federal spending. In this financial climate, national forest budgets were reduced by 24 percent, from $2.8 billion in 1980 to $2.1 billion (constant 1994 dollars) in 1986, and remained at reduced levels, an average of $2.4 billion, through 1994. National forest staffing was similarly reduced, by 26 percent, from 41,700 FTE's in 1980 to 30,900 in 1988. Staffing recovered somewhat in 1989 and reached an average of 34,500 FTE's between 1992 and 1994 (USDA Forest Service 1994f).

Despite funding and staffing reductions, national forests continued to balance staffing among the resource disciplines and improve their capabilities for managing multiple uses on the land in a more integrated manner. For example, staffing for timber programs, including timber sales, silvicultural examinations, resource planning, and all reforestation, timber stand improvement, and brush disposal activities, declined by 18 percent, from about 12,900 FTE's in 1980 to 10,500 in 1994. Much of this reduction reflected the sharp drop in timber sales during the early 1990's. On the other hand, staffing for soil and water programs increased by 40 percent, from 1,170 FTE's in 1980 to 1,640 FTE's in 1994. Wildlife and fish FTE's increased by 114 percent, from 1,040 to 2,230. Recreation program staffing rose by 49 percent, from 3,420 FTE's to 5,100 FTE's. Road and facility engineering staffing, as with staffing for timber programs, also declined, by 64 percent, from 5,220 FTE's to 1,860. Staffing for minerals management, however, increased from 230 to 400 FTE's, or by 66 percent. Range management staffing declined from 1,090 FTE's to 920, or by 16 percent (USDA Forest Service 1994f).

The rapid growth of national forest use abated between 1980 and 1995. Timber sale offerings and volumes sold during the 1980's averaged 11.5 and 10.7 bbf, respectively, about the same as the 1970's decade, then both dropped sharply during the early 1990's to less than 4.0 bbf by 1994. The decline was concentrated in the Pacific Southwest and Pacific Northwest Regions, but all regions except the Eastern Region experienced a decline in timber sale levels. In the early 1990's, timber sales in the Eastern Region, a predominantly hardwood region, averaged 710 million board feet — 17 percent above the 1980 level. Permitted grazing capacity remained more or less stable at 9.8 million AUM's per year, but actual range use declined from 8.7 million AUM's in 1992 to 8.1 million AUM's in 1994

Recreation visitor day (RVD) use, including wildlife, fishery, and wilderness use, actually experienced a 4 percent decline by 1987, and then began to increase again at 3.4 percent per year to 1994 — substantially faster than the 1 percent population growth rate. The overall average rate of increase for the 15-year period from 1979 to 1994 was 2.2 percent.

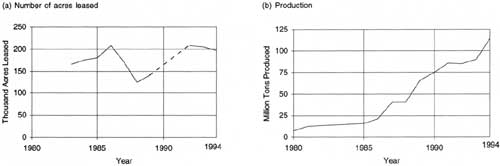

NEPA and NFMA regulations and court injunctions increased the need for more intensive oversight of mining plans and operations. Mineral management activities responded with more thorough environmental assessments and protection standards. The number of producing gas, oil, coal, and geothermal leases increased during this period, while the acreage under lease for exploration and production decreased.

This general respite from the dramatic increases in national forest use of the previous three decades, however, did not bring any slackening of the public controversy associated with national forest land and resource planning and management or the public's interest in participating in that planning and management (USDA Forest Service 1981b, 1994e, 1994f).

The Role of Public Participation and Growing Confrontation

The passage of NEPA, RPA, and NFMA legislation during the 1970's greatly broadened the opportunities for a wide range of people and organizations with highly diverse expectations and sharply differing values, preferences, and viewpoints to become involved in national forest planning, decision making, and project implementation. These opportunities rose to new heights between 1980 and 1995 as NFMA planning, framed by NEPA's requirements for environmental impact analysis, got under way. Public participation in national forest planning activities literally exploded. NFMA planning for the 123 national forests, as reported in 25 draft and 97 final forest planning environmental documents, involved more than 72,000 public input events (table 4) (Russell et al. 1990).

Table 4. Number of public input events by type of event

| Type of Event | Number |

| Meetings Held | 1,216 |

| Brochures and Newsletters Produced | 650 |

| Contacts and Consultations Made | 6,651 |

| Letters of Response Received | 63,607 |

| Total | 72,124 |

Source: Russell et al. 1990. | |

Many more thousands of citizens participated in meetings, in preparing brochures and newsletters, in direct contacts and consultations with national forest managers, and in review and comment on draft EIS documents. About 90,000 copies of NFMA plans and supporting EIS documents were distributed to public policy officials, public agencies, private organizations, and individuals for review and comment.

NEPA, RPA, and NFMA intended that the public's views and ideas on national forest planning and decisions be solicited and taken into account during the development of both draft and final plans and decisions. Legislators and the Forest Service hoped that a wide range of the public would be interested in forest planning and that such interest would lead to fewer appeals and court suits on final national forest plans, EIS's, and decisions. But the public's expectations were very diverse and strongly held. Environmental groups believed NFMA mandated national forest management reform — reform that would involve a change from what such groups viewed as a dominant commodity production focus to a focus on increased protection and enhancement of noncommodity uses, especially the expansion of wilderness areas. Timber industry groups looked for forest plans to achieve the high RPA-set timber production targets more effectively to meet the national demand for wood products. Other groups identified success in terms of their own particular expectations (Larsen et al. 1990).

Growing Public Confrontation

As NFMA plans and resource management projects were developed, completed, and implemented during the 1980's, public participation grew, and debates about the appropriate use and management of the national forests increased and intensified. Growth in public participation led to an increasing number of challenges as individuals and groups turned to the press, demonstrations, the Forest Service administrative appeals process, court suits, and legislative actions to pursue their goals. By the end of the 1980's, the number of new appeals, for example, had risen to more than 1,000 per year. Such challenges focused primarily on timber harvest and management, but every resource area was affected by them.

Plan and project appeals were directed to the deciding officials and, therefore, were predominantly local — 56 percent went to regional foresters and 33 percent to forest supervisors. Only 11 percent were directed to the Chief of the Forest Service or the Secretary of Agriculture.

Environmental interest groups increasingly turned toward appeals, national public opinion, and interventions by judges and sympathetic congressional authorizing committees to achieve their national forest management goals. Between 1980 and 1995, these groups became increasingly sophisticated and successful in pursuing their goals through court suits, political campaigns, and legislative action — a success that was epitomized by the resolution of the northern spotted owl issue in the Pacific Northwest (Hoberg 1993). A 1993 court injunction and the Northwest Forest Plan adopted in 1994 for the management of the northern spotted owl habitat led to a reduction of several billion board feet in old-growth timber harvests on Pacific Northwest national forests in favor of maintaining a more extensive old-growth environment to protect the viability of the threatened northern spotted owl populations and other old growth-dependent species.

Thus, while public participation brought significant increases in public input to national forest planning between 1980 and 1995, it also increased and intensified issues and debates between national forest managers and the public about the appropriate use and management of national forests. Chief Robertson, addressing the Lands Committee of the Rocky Mountain Oil and Gas Association in 1988, characterized the environmental community as "extremely vigilant" and "watching every step we make on national forests and standing ready to challenge any decision that has a weak spot" (Robertson 1988).

The National Forest Planning Process and Its Performance

Initially, many national forest managers were hopeful that the NFMA planning process would be largely scientific and produce scientific solutions that would avoid political entanglements — an assumption that tended to shape the public participation process. Lofty expectations accompanied this approach. Its goal was to inform and involve the public — to give the public information and to receive public input — as opposed to problem resolution through two-way communication, negotiation, and shared decision making. The new forest plans were expected to be more balanced in terms of resource coordination and integrated management for the multiple uses and better understood by the public, thereby earning more public support and producing fewer appeals and litigation. National forest managers hoped, as expressed by Senator Hubert Humphrey, that "forest managers could practice forestry in the forest and not in the courts." The public had similar high hopes. Neither the public nor national forest managers anticipated the influence that the changing values emerging among public interest groups and the maturing of the environmental movement would have on the process. NFMA planning quickly became much more confrontational and political than ever expected. As a result, the planning process became increasingly complex and demanded and consumed more time (Larsen et al. 1990a).

The Public Issue and Management Concern

The NFMA planning process was designed to respond to the 1980 RPA national program goals at the local forest level. RPA projected modest increases in all national forest resource uses by 1995 and major increases in outdoor recreation uses, including wildlife, fisheries, and wilderness; timber harvests; and mineral and energy operating plans, by the year 2030. These projections largely reflected past national forest resource use and demand trends, including a strong response to the newly established demand for substantial expansion of national forest wilderness. This raised both public interest and public concerns.

The planning process provided a forum for addressing and resolving national forest resource use issues and management concerns that emerged from the public's very diverse and conflicting interests. In practical terms, the purpose of the forest plans was to provide answers to three questions: What is a forest good for (its ecological potential)? What do people want from the forest? and How do we meet today's needs, while preserving future options? (Shands et al. 1990).

One of the initial steps in the planning process established each forest's baseline or potential for each of the major resource uses. These capacity limits defined the outer boundaries of the forest planning process. The second step was the identification of issues and opportunities by the public and planning and management concerns by national forest managers. Public issues basically defined the alternatives to be considered. Also, they often reflected and defined longstanding conflicts among competing national forest uses and user interests. In a way, they represented highly politicized public policy questions. Forest planning, however, tended to respond to these issues as management problems and addressed them through the largely scientific and technical planning process (Shands et al. 1990). The commitment of the forest planning process to the 1980 RPA's long-term output goals and objectives tended to orient the planning process toward traditional multiple-use planning and management. Such a technical planning approach did not respond well to the social and political content of the public issues and did not provide an arena for public interest groups to confront each other and work with policy officials toward mutually acceptable solutions. As a consequence, external pressure on national forest planning mounted. The 1980's were marked by an increased number of appeals and litigation that focused heavily on limiting or reducing the commercial uses of national forests, particularly timber harvesting.

The Role of Planning Alternatives and Management Direction

The public issue process revealed the public's wide scope of expectations for national forest use and management. Thus, there was a corresponding variety of alternative ways national forests could be managed. Taken collectively, these reflected the full diversity of the public's expectations, RPA program goals, and existing management plans and goals. The preferred management alternative was determined and selected by comparing the net public benefits (the discounted market value of all future uses less management costs) of the alternatives and how they responded to the various public issues.

National forest planning alternatives typically included the existing forest plan or plans as the NEPA-required "no action" alternative, and a specific alternative that responded to the RPA goals. Other alternatives could include high, moderate, and low commodity-output options and a similar set of amenity alternatives. Still others might focus on wilderness, wildlife and fisheries, or recreation, or address a particular public issue. A few forests included an alternative that was defined collectively by conservation interests or other interest groups.

Because of their long-term nature, forest plans were goal-oriented and did not specify actual year-by-year on-the-ground implementation. In other words, forest plans were not project- or site-specific. This became quite a problem for many interest groups who expected forest plans to make site-specific decisions. Their expectations led to many forest plan and project appeals. Each year, national forests made decisions on about 40,000 resource management projects — an average of 325 per national forest per year. Over the 10- to 15-year expected life of a forest plan, the inclusion of such projects in the forest planning process would have entailed advance planning and decisions for 3,250 to 4,875 site-specific projects per forest (Gippert and White 1990).

Management Direction for Implementing Alternatives

The management direction for each alternative was determined by its long-term goals for resource use. It also reflected the direction given in the laws and regulations and the influence of scientific knowledge, technology, and experience, but did not assign any specific forest management activities. Such management direction likewise provided for the protection of soil productivity and environmental quality. In addition, there were environmental guidelines and standards, referred to as "management constraints" (management requirements) to ensure viable wildlife and fish populations, meet State water quality standards, and protect endangered species. Each alternative mapped national forest lands into management areas (land use "zones" ) reflecting different resource conditions and potentials for use — each area uniform enough to have its own management direction for expected uses, environmental protection, and mitigation. Most forests had about 20 management areas. The planned resource goals and uses among these management areas varied with each alternative, and the management direction likewise varied accordingly.

Many forests were able to design management direction in ways that mitigated or resolved certain public issues. The most successful forests were able to distill their public issues into problem statements. The management direction for each management area then served to resolve such issues. This approach appeared to help the public visualize what would take place on the forest in better detail and tended to increase the public's acceptance of planning decisions (Bosworth et al. 1990).

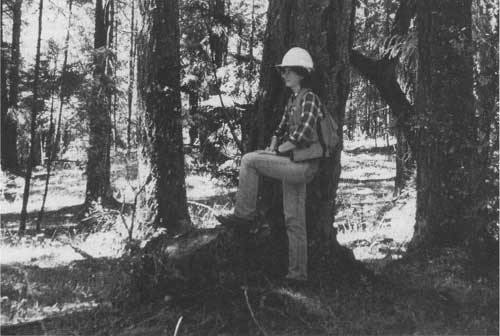

|

| Forester examining silvicultural practices on Douglas-fir, Siskiyou National Forest, Oregon. (USDA Forest Service Photo. Taken by Melissa Carlson.) |

Principal Guidelines for Planning Multiple Uses

NFMA affirmed the management of national forests for multiple uses. It defined many constraints that explicitly provided for the protection of soil, water, and especially wildlife and fisheries. It also provided strong guidelines for implementing the interdisciplinary approach.

NFMA guidelines and regulations also focused strongly on the timber resource. Timber harvesting would be limited to forested lands where the soil, slope, and other watershed conditions would not be irreversibly damaged and where there was an assurance that the land could be successfully restocked with trees within 5 years following timber harvest. Streams, lakes, shorelines, and other wetlands would be protected from detrimental changes associated with timber harvesting. Clearcutting would be limited to conditions where it was determined to be the best-suited or optimum method to meet land management objectives and not necessarily the one that produced the greatest dollar return or timber volume. Clearcut size would be restricted.

NFMA guidelines and regulations also permitted increased harvest levels based on intensified management, but only if such management was consistent with the MUSY Act of 1960 and successfully implemented. Timber harvesting, except for salvage sales or sales needed to protect other multiple-use values, was precluded on lands classed as not suited for timber production.

Each forest's harvestable volume was limited to the amount that could be removed annually, in perpetuity, on a long-term sustained-yield basis. A forest plan could depart from such a nondeclining flow level, but only where the increased volume provided by the departure helped to achieve one or more other multiple-use management objectives, determined with public participation, in the forest plan.

NFMA also provided for maintaining the diversity of plant and animal communities on each national forest. Its regulations required that fish and wildlife habitats be managed to maintain viable populations of existing native and desired nonnative vertebrate species in the planning area to ensure that such species did not become threatened or endangered. Forest plans were also to protect and restore habitats of any endangered species that existed in the planning area to sustain their populations. This direction responded to ESA's policy objectives and direction.

NFMA called for integrating economic analysis with biological considerations. This was achieved by defining alternative forest resource management practices that would satisfy NFMA's and NEPA's biological and environmental constraints and by selecting the practices that would achieve the resource output goals most efficiently based on their expected rate of return on investment costs. This procedure was most useful in planning the management direction and timberland area needed to achieve the timber management goal.

The plan's EIS was to discuss the environmental impacts for each forest plan alternative. It was also to address social, economic, and community impacts as well as the biological and physical resource effects. Although NFMA itself was vague about the need to assess community impacts, national forest managers needed to be responsive to community concerns and the impacts that plan alternatives had on a community's stability and viability. Generally, this meant planning national forest management in a way that would avoid radical or abrupt changes in a community's economic and social structure.

The Interdisciplinary Process

NFMA required that each national forest use an interdisciplinary team to develop its forest plan. The role of the interdisciplinary team was to ensure that forest planning would fully consider the physical, biological, economic, social, and other sciences in the long-term planning and management direction for multiple uses — a requirement that was intended to replace the strong role of the traditional multidisciplinary "planning by individual resource function" approach to national forest management. The interdisciplinary team requirement broadened the professional skills available on each forest. The hiring of new and more "ologists" over time contributed to a more evenhanded interdisciplinary approach in developing forest use plans and management direction for each of the multiple uses in each management area (Office of Technology Assessment 1992).

In 1990, a Forest Service retrospective evaluation of the interdisciplinary process, based on comments and responses from 178 key local people in all national forest regions, found that the public had very favorable views about the process. They generally believed that the interdisciplinary process allowed all resources to be appropriately considered and, in this way, helped to achieve more sound management decisions. The interdisciplinary approach also enabled more environmental issues and impacts to be assessed than previous planning approaches. Both the responding public and national forest professional staff believed that the interdisciplinary process produced far better multiple-use coordination than earlier multidisciplinary planning methods had (O'Neal et al. 1990).

The Plan Decision Process: Plan Approval, Appeals, and Litigation

The draft EIS displayed the environmental analysis process and its results and provided initial information for evaluating plan alternatives and identifying a preferred alternative. All alternatives were designed to meet environmental protection objectives and resource management constraints. Alternatives were compared by estimating the net public benefits of each alternative, various indicators of each alternative's response to public issues, and the RPA goals for individual resources.

The Preferred Alternative

The selection of a final alternative was based on the public's review of and response to the forest plan's draft EIS and its preferred alternative. Frequently, the public feedback led to adjustments and modifications in the preferred alternative or the selection of another alternative. The regional forester for each region selected the final alternative, issued a final EIS, and documented the decision in a record of decision. Such a decision could be appealed to the Chief of the Forest Service.

Once plans were approved, they became the legal guide for developing annual program and budget proposals. Management direction provided the starting point for implementing the management of multiple uses and their planned annual outputs on the ground. The actual implementation of forest plans, however, was controlled by congressional budget allocations to national forests, which influenced the scheduling and timing of resource outputs and management practices to be used and also the general resource management emphasis (Bosworth et al. 1990).

Forest Plan Appeals

The number of forest plans completed each year is displayed in table 5, together with information on the number of new appeals, resolved appeals, pending appeals, and forest plans free of appeals (USDA Forest Service 1981-1995, 1995e).

Table 5. Appeals of completed forest plans by number, status, and year

| Years | Forest Plans with EIS filed with EPA |

New Appeals |

Appeals Resolved |

Appeals Outstanding |

Forests Free of Appeals |

| 1983 | 4 | — | — | — | |

| 1984 | 5 | 24 | 22 | 2 | — |

| 1985 | 14 | 31 | 23 | 10 | 5 |

| 1986 | 42 | 230 | 41 | 199 | 12 |

| 1987 | 17 | 151 | 117 | 233 | 24 |

| 1988 | 8 | 317 | 184 | 366 | 39 |

| 1989 | 7 | 84 | 155 | 295 | 49 |

| 1990 | 17 | 182 | 128 | 349 | 62 |

| 1991 | 123 | 117 | 355 | NA | |

| 1992 | 4 | 57 | 122 | 290 | 78 |

| 1993 | 0a | 40 | 99 | 231 | 79 |

| 1994 | NA | 3 | 29 | 205 | NA |

| 1995 | NA | 3 | 24 | 184 | NA |

| Total | 123 | 1245 | 1061 | 184 | — |

aFinal EIS delayed on four California national forests due to need to revise previously completed draft plans in response to the listing of the spotted owl as a threatened species. Source: USDA Forest Service 1981-1995, 1995e. | |||||

As more plans were completed and final EIS's issued, plan appeals escalated to a peak level in 1988 and then declined. Forest plan appeals through 1995 totaled 1,245. The number of appeals per plan or forest varied from a low of 5 to a high of 25. In 1995, there were still 184 appeals outstanding — about four appeals per plan. Table 6 summarizes the resolution of forest plan appeals (USDA Forest Service 1995e).

Table 6. Resolution of forest land and resource management plan appeals

| Resolution of Appeal |

1984-1989 | 1990-1995 Number |

Total |

| Appeals on Plans Remanded to Forest | 37 | 7 | 44 |

| Appeals on Plans Affirmed | 132 | 329 | 461 |

| Appeals Nonsubstantive | 70 | 62 | 132 |

| Appeals Dismissed | 179 | 41 | 220 |

| Appeals Withdrawn | 127 | 77 | 204 |

| Totals | 545 | 516 | 1061 |

Source: USDA Forest Service 1995e. | |||

The record of appeal resolutions suggests that appellants' actions were not very effective for their purposes, which belies the actual case. The contents of all appealed plans received careful evaluation in the Chief's Office. In order to be prepared to provide effective responses to a Chief's Office appeal evaluation, most forests reviewed their plans critically. As a result, many appeals were withdrawn through negotiated agreements for revisions and amendments with national forest planning officials below the Chief's level. The dismissals generally reflected untimely appeal submissions, appeals for remedies not legally available to national forest managers, or issues that were outside the scope of the planning effort. The appeals on procedure (nonsubstantive appeals) were concentrated on just two national forest locations — the Los Padres National Forest in California and those involved in the northern spotted owl issue in the Pacific Northwest — and were essentially dismissed. More than 90 percent of the decisions on substantive appeals affirmed the final EIS and its selected final forest plan.

Only 44 of the substantive appeals were remanded to the forests for further review and consideration of the appeal issue and forest-level revision or amendment. Most of the remanded appeals (37) occurred with the earlier completed plans and appeals made before 1990.

Although almost all of the planning appeals resulted in affirmed plans or were dismissed or withdrawn, they raised issues that led to improvements in the planning process, the quality of the disclosure of the environmental impacts in the final forest plan, and the management direction published in the final EIS documents. These improvements appear to be reflected in the relatively fewer number of remands between 1990 and 1995 — 5.1 percent of 136 substantive appeals that were not dismissed or withdrawn compared to 21.9 percent of the substantive appeals not dismissed or withdrawn between 1985 and 1989. In addition, the number of appeals that were dismissed or withdrawn declined substantially after 1989 (table 6). However, relatively more appeals were referred to the Chief for affirmation or remand. This trend indicated more effective presentation of appeals by appellants and relatively fewer negotiated settlements of appeals at the forest level.

NEPA and NFMA Forest Planning Litigation

Some public interest groups and individuals pursued their dissatisfaction with approved forest plans through court suits and adjudication. The number of such suits, however, was much less than the number of forest plan appeals. The first forest plan to be challenged in litigation was the Rio Grande (Colorado) National Forest plan. Between that initial court challenge in 1987 and 1995, a total of 49 court suits relating to national forest plans were adjudicated. This compares with the resolution of 1,061 out of 1,245 forest plan appeals without court suits during the same period. In 39 of the 49 suits (80 percent of the time), the courts upheld the forest plans. In addition to the approval of the forest plan itself, most of the suits involved timber harvest or management issues or biological diversity, endangered species, and wildlife or fisheries management issues. Other suits addressed issues related to range, recreation, roadless area evaluation, water rights, public involvement, watershed effects, old growth, minerals, road development, or, in a few instances, regional guidelines, but at a lower frequency than timber and wildlife issues.

The 10 court suits adjudicated in favor of the plaintiffs generally involved either timber management or endangered species issues or both, including the spotted owl and the salmon species issues in the Pacific Northwest. All but one of these suits related to forest plans in the Pacific Northwest or the northern Rocky Mountains.

Project-Level Appeals and Litigation

As national forest plans were increasingly affirmed through the appeals process and court litigation, public interest groups and individuals increasingly turned to challenging the implementation of site-specific projects to pursue their particular concerns about national forest management. The number of project appeals awaiting decisions rose rapidly, from 163 at the beginning of 1986 to 1,626 at the end of 1992 (table 7).

Table 7. Summary of project appeal activity, 1986-1992

| Appeal Status | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1989 | 1990 | 1991 | 1992 |

| Number of Appeals | |||||||

| Pending January 1 | 163 | 563 | 628 | 1,044 | 1,045 | 1,249 | 1,453 |

| New Appeals | 1,081 | 874 | 1,609 | 1,291 | 1,991 | 1,386 | 1,659 |

| Decisions Rendered | 681 | 809 | 1,193 | 1,290 | 1,787 | 1,182 | 1,486 |

| Pending December 31 | 563 | 628 | 1,044 | 1,045 | 1,249 | 1,453 | 1,626 |

Source: USDA Forest Service 1992a. | |||||||

New appeals in 1986 numbered 1,081, compared with 1,659 in 1992, and totaled 9,983 for the 1986 to 1993 period (includes 1,144 forest plan appeals). Appeals resolved in the same period rose similarly, from 681 to 1,486, but this increase was not great enough to catch up with the growing workload of pending and new appeals.

The appeals focused most heavily on timber sales and management issues (table 8). For 1991 and 1992, such appeals constituted 52.6 percent of the new appeals, while recreation, range, land management planning, minerals and geothermal management, and lands administration each constituted between 6 and 11 percent. Most appeals related to resource management projects; only 201 related to land management planning.

Table 8. Distribution of administrative appeals related to national forest management for 1991 and 1992

| Resource or Management Activity |

Number of Appeals |

Percent of Total |

| Timber | 1,530 | 52.6 |

| Recreation | 320 | 11.0 |

| Land Planning | 201 | 6.9 |

| Minerals | 220 | 7.6 |

| Range | 182 | 6.3 |

| Lands | 189 | 6.5 |

| Wildlife/Fish | 126 | 4.3 |

| Engineering | 62 | 2.1 |

| Pest Management | 13 | <1 |

| Water/Air | 8 | <1 |

| Other | 60 | 2.1 |

| Total | 2,991 | 99.4 |

Source: USDA Forest Service 1992a. | ||

Many of the project-level appeals were filed by interest groups and individuals pursuing issues that they felt had not been fully responded to or resolved in approved forest plans and EIS's or actions on plan appeals. The appeals were widely distributed throughout the National Forest System. The greatest concentration, almost 73 percent of all the appeals in 1991 and 1992, were in the major timber-producing regions: Pacific Northwest (Region 6), Northern (Region 1), Southern (Region 8), and Pacific Southwest (Region 5). Thus, public issues and appeals did not abate as national forest plans were approved for implementation and as forest plan appeals were increasingly resolved. The focal point for appeals merely moved from forest plans to site-specific projects.

After 1988, litigation accelerated. The number of NEPA cases litigated rose from 50 between 1970 and 1988 to 79 for between 1989 and 1995. However, the Forest Service success ratio on NEPA court suits rose from 20 out of 47 cases (43 percent) between 1970 and 1978 to 63 out of 79 cases (80 percent) between 1988 and 1995 — a fact that was largely attributed to the Forest Service's commitment, beginning in 1979, to provide Service-wide intensive training and preventive law advice on NEPA's legal requirements, its related decision documents, and its effective implementation in an effort to help meet the growing challenge of NEPA compliance (Bremen 1995). This initiative contributed importantly to more effective responses to NEPA standards and requirements, as well as to better written NEPA and decision documents.

National Action Plan To Improve NEPA Compliance

In 1988, the escalating number of project appeals and the high level of adverse NEPA court suits led the Forest Service to establish a national task force to determine the underlying causes of this performance. There was a growing concern within the Forest Service that the trend of increasing litigation and appeals would significantly change the balance of management activities on national forests and disrupt timber sales and oil and gas leasing, particularly in unroaded areas and old-growth timber. The task force reported three basic problems requiring correction to achieve more effective NEPA compliance and minimize future litigation and appeals: an often insufficient understanding of NEPA requirements among national forest managers and staff; widespread reluctance within the Forest Service to prepare EIS's; and confusion about when specific planning, management, and NEPA-related decisions were made (USDA Forest Service 1989a). Citizens participating in the NFMA planning process also shared the last concern.

This evaluation resulted in A National Action Plan: Improving Compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act in Project Decisionmaking (Leonard 1989). The action plan involved formal participation of Forest Service leadership from the Chief down to the district ranger and all professional staff involved in preparing environmental analyses. It focused on removing the obstacles national forest managers and staff faced in trying to comply with NEPA and NFMA when analyzing, designing, and deciding on resource management projects. Such obstacles included pressures brought on by heavy, time-consuming workloads and a tendency to cut corners to meet planned program and budget targets — particularly, but not exclusively, for timber harvests; unclear signals on priorities; lack of clear, accessible direction on NEPA compliance; changing interpretation and direction; paperwork overload; and changing analysis standards for assessing environmental impacts.

Formally implemented in the spring of 1989, the National Action Plan's short-term actions included a letter to line officers with Chief's direction, followed up by joint Deputy Chief and regional management meetings; regional action plans and inventories of available NEPA resources and skills; national team assistance on specific projects; a national newsletter on NEPA compliance; a national training workshop with followup on how to help interdisciplinary planning teams and EIS teams; and a state-of-the-art "answer book" with references.

Longer-term activities included a high-quality training course on NEPA and NFMA appeals and litigation processes and requirements as well as other, more specialized courses, including training in conflict resolution, the development of analytical models for estimating environmental impacts, and the expansion of the national database and library on NEPA compliance needs.

The national effort to improve NEPA compliance was applied effectively and energetically throughout the National Forest System. It continues to operate, and its activities have improved and expanded with time and experience. The best evidence of its effectiveness is the major reversal of the ratio of appeal wins versus losses since 1988. The number of new NEPA appeals and suits, nevertheless, has continued to grow, indicating dissatisfaction with national forest use and management among strong residual segments of public interest groups and individuals, which include commodity as well as environmental interests. Their attention generally focuses on commercial uses of the forest and related environmental concerns, and particularly on timber harvesting and management and its perceived environmental effects. In view of the progress national forests have made in meeting NEPA requirements and standards, it raises a question about the goal of the growing number of appeals and suits. Improved national forest NEPA compliance indicates more effective responses to Federal laws setting environmental standards that national forests management must satisfy. Under these circumstances, one would normally expect NEPA compliance appeals and suits to decline rather than rise. However, appeals and litigation are a means of stopping or more thoroughly exploring management decisions that are not favorable to a group's or individual's interests. Some groups became quite sophisticated in the pursuit of these interests. One group, the Wilderness Society, for example, published two handbooks How to Appeal Forest Service Plans and Issues to Raise in a Forest Plan Appeal (Wilderness Society 1986a, 1986b).

Revision of the Rules of National Forest Land and Resource Management Planning

In March 1989, as an initial step for revising and updating the existing rules for the second cycle of national forest planning under NFMA, the Forest Service undertook a comprehensive review and critique of its land management planning experience. The critique, completed in May 1990, documented what had been learned in the first cycle of NFMA planning and suggested the best ways to respond to the planning challenges of the second cycle. A summary report, Synthesis of the Critique of Land Management Planning, Volume 1 (Larsen et al. 1990a), and 10 other, more detailed reports documented the results. The critique involved more than 3,500 people inside and outside the Forest Service. More than 2,000 people participated in or had responsibilities for planning and providing guidance through formal workshops and interviews. They included members of the general public, interest groups, representatives of other resource management agencies, elected officials, Indian tribal leaders, forest supervisors, regional foresters, resource specialists, and members of interdisciplinary planning teams. An additional 1,500 interested people submitted written comments on the planning experience of the 1980's.

The findings identified six major areas where adjustments were needed: citizen, lawmaker, and Forest Service expectations of planning; the Forest Service attitude toward and conduct of public involvement; how the Forest Service conducts planning; simplification and clarification of planning procedures; implementation of plans, particularly to ensure that they are followed and used; and connections between appropriations and forest plans.

Some 272 detailed recommendations were combined into seven major recommendations:

Reduce and clarify planning rules and direction, including a planned, step-by-step approach to forest plan revision and increased responsibility and authority of local resource managers.

Inform and involve public interests early and continuously; increase line officer commitment to planning and improve analytic tools and their application to planning questions.

Ensure that planning is adequately staffed with the variety of skills it needs and that research support is adequate to increase the effectiveness of integrated resource management.

Strengthen and clarify the linkage between forest plans, programming and budgeting, and appropriation activities.

Educate the national forest staff, citizens, and cooperators about the RPA, NFMA, and NEPA planning processes and how they fit into the national forest multilevel planning, decision making, and management processes.

Develop a strategy for revising forest plans and improve methods for monitoring and maintaining forest plans.

Strengthen Forest Service quality control and management review mechanisms and disseminate results together with decisions from appeals and litigation to interested public (Federal Register 1991).

The critique's findings became valuable guidance in preparing the Forest Service's draft proposal to change land management planning regulations. The Forest Service published an advance notice of proposed rulemaking in the Federal Register in February 1991 (Federal Register 1991), soon after Synthesis of the Critique of Land Management Planning was published, to solicit comments on the draft planning regulations. The advance notice of rulemaking's text was strongly based on about a third of the critique. Readers were encouraged to study the critique's reports along with the preliminary text. Other reviews and informational papers used to update the existing rule were the results of land management plan appeals and litigation, various published professional papers on the planning process, and related papers such as the Keystone Policy Dialogue, which addressed biodiversity on Federal lands. The advance notice restated the Forest Service's conclusion that although NFMA had some limitations, it was basically sound policy guidance. NFMA, for example, did not specifically address the ecosystem concept and management approach to national forest land and resource management planning, but the critique included a recommendation to "take an ecosystem approach to multiple-use, sustained-yield management . . . in contrast to a resources approach...." (Shands et al. 1990). The advance notice's proposed regulatory text moved in that direction in its purposes and principles. It emphasized the need to manage national forest multiple uses, including environmental and amenity values, in an ecologically sound manner. Under integrated resource management, the proposed rule included ecological subunits such as biological communities and special habitats as management indicators in addition to the traditional management indicator species.

The Forest Service distributed 20,000 copies of the advance notice to interested persons and groups and invited comments on the rule. More than 600 responses provided 4,700 comments. Business and industry interests; Federal, State, and local government agencies; conservation and environmental groups; and Forest Service employees each provided between 9 and 11 percent of the comments, for a total of 41 percent. Recreation and other user groups, academics, and civic organizations each provided 1 to 2 percent of the comments — a total of 4 percent. The remaining 55 percent came from individuals. (Federal Register 1995). Following the processing of the comments on the 1991 advance notice, there was an extended delay in publishing a proposed rule — until 1995. The delay was influenced institutionally by a Bush Administration moratorium on the issuance of new regulations, the change in Administrations after the November 1992 presidential election, and a need to review the proposed rule making with the new Clinton Administration policy officials. Chief Robertson's 1992 announcement of the intention to move the National Forest System toward an ecosystem approach in managing multiple uses added a new technical dimension to NFMA rule making not addressed in the advance notice. The continuing northern spotted owl controversy in the Pacific Northwest in the early 1990's — a focal point for exploring ways to implement principles of ecosystem management — remained unsettled until late 1994. It created its own uncertainties and tensions about implementing an ecosystem approach to national forest management. There also were substantial litigation and court decisions in this period; these continually introduced new considerations about how and to what extent ecosystem management guidelines could be introduced into the NFMA regulations (Federal Register 1995). The Forest Service finally published its proposed rule in the Federal Register in April 1995. The proposed rule included a major new Forest Service finding and conclusion: "Principles of ecosystem management need to be reflected in the planning regulations."

The Forest Service has made its intention to move toward an ecosystem management approach clear and, in the last few years, it has actively promoted implementing ecosystem principles consistent with existing laws. Other Federal agencies have acted similarly. When the spotted owl controversy in the Pacific Northwest was settled in 1994, it became a particular case in point. The 9th District Circuit Court upheld the validity of an ecosystem approach in sustaining the Record of Decision for the Range of the Northern Spotted Owl from programmatic challenge (SAS v. Lyons, No. C92—479WD [W.D. WA Dec. 21, 1994]). Judge Dwyer, in rendering that decision, stated, "Given the current condition of the forests, there is no way the agencies could comply with environmental laws without planning on an ecosystem basis" (Federal Register 1995).

The Forest Service recognizes that the ecosystem approach to management is an evolving concept and that much remains to be learned about how best to implement its principles practically in managing multiple uses. The Forest Service issued the proposed rule as a transitional step for incorporating the principles behind the ecosystem approach into land and resource management planning consistent with NFMA. Although the existing "crazy quilt" framework of Federal laws occasions some limitations and uncertainties for implementing ecosystem concepts, progress can be made within this framework. The Forest Service believes that existing statutes may need to be adjusted before the ecosystem approach can be transformed from an evolving approach to a fully operational reality for the National Forest System (Federal Register 1995).

The proposed planning rule's first principle requires that the National Forest System be managed to provide sustainable ecosystems that yield multiple benefits to present and future generations. It then defines people as a part of those ecosystems and defines the primary role of resource decisionmaking as meeting people's needs and desires within the capacities of those ecosystems.

Forest plans will establish direction for the integrated management of soil, water, fish and wildlife habitat, grazing, timber, oil, gas, mineral, recreation, wilderness, cultural, historic, geologic, vegetative, air, visual, and other relevant resources.

Management direction will focus on achieving objectives that will be described in terms of desired resource conditions, or ranges of conditions, associated with ecosystem variations.

Objectives will be designed to achieve forest plan goals describing desired end results in broad general terms. These forest plan goals will link broad Forest Service goals expressed in the law, Executive Orders, regulations, or Forest Service directives and the RPA program to the desired resource conditions specified in the forest plan.

The forest plan will not specify a time period for achieving its goals and objectives. Actually, the desired resource condition will be the basis for determining the capability of local national forest ecosystems to meet the multiple uses sought by national forest users.

Under the proposed NFMA planning regulations, projections of goods and service levels or management activity levels would not be any part of forest plan direction. Experience with existing plans has shown that such projections are not reliable or predictable and are often not even determined by the plan; rather, they are determined by annual budgets and programs, actual market demands, and by appeals and litigation — processes and decisions not under the control of national forest managers. Thus, the state of forest resource conditions desired for soils and rangelands and other vegetation, historic or cultural site retention, or visual quality or wilderness experience and the associated management direction would determine the forests' capability to respond to them. The proposed rule also assumes that effective ecosystem management, properly implemented, including the management of endangered, threatened, and sensitive species habitats to avoid their extirpation or listing in the case of sensitive species, would automatically provide for habitat diversity as well as sustainability. The proposed rule focuses forest plans on achieving and sustaining desired resource conditions and responding to multiple-use demands according to the capacity of those ecosystems to supply them. Thus, forest plans would no longer include quantitative outputs except in the case of timber resources. NFMA explicitly requires quantitative output objectives for timber.

Under the proposed rule, national forest management would, in some ways, become more holistic, increase its emphasis on an interdisciplinary approach, and seek more effective public participation to integrate the management of its multiple resources and uses. The ecosystem approach would involve a broader geographic and landscape-oriented perspective in fitting the multiple uses into forest ecosystems. It would also consider conditions on other public and private lands outside the forest plan area to ensure that national forest lands are managed from a broad, ecological perspective rather than one limited to jurisdictional boundaries. This effort will involve improved and increased public participation to avoid impinging on the rights of private landowners and the authorities of other public agencies.

The proposed rule provides still another approach to integrated management of multiple uses in a way that will sustain both the forest uses and the ecosystems that support them for the benefit of future generations. Its final form will depend upon the public comments on the purpose and content of the proposed rule closed in August 1995. A second proposed rule was drafted in response to the public comments and, as of March 1997, had been scheduled to be reissued for an additional 90-day comment period in mid-1997. It is still pending as this book is being published.

Wilderness Designation, Use, and Management

Between 1980 and 1995, public interests prompted congressional wilderness designations that more than doubled the area of national forest wilderness (see fig. 17, chapter 5). Most of these additions had been included in RARE II. Between 1979 and 1984, the designated national forest wilderness area rose by 17 million acres, from 15.1 million to 32.1 million, and the number of units nearly tripled, from 110 to 327, creating a huge challenge for wilderness administration and management. Designations in subsequent years came more slowly. Between 1985 and 1993, national forest wilderness grew by 2.6 million acres, to 34.6 million acres, with 397 units in 38 States. Nearly 93 percent of the wilderness area (32 million acres) was distributed among 254 units in 14 States in the Pacific Coast and Rocky Mountain Regions and Alaska. The remaining 7.4 percent (2.6 million acres) was dispersed among 143 units in 24 States in the eastern and central United States. Wilderness areas constituted 18 percent of the total National Forest System in 1993, 36 percent of the total National Wilderness Preservation System, and 74 percent of the wilderness in the lower 48 States. In 1994, Congress was considering an additional 6 million acres of national forest land for wilderness designation.

Wilderness use grew in the 1980's, but at a slower rate than during the 1970's. RVD use rose from 9.6 million in 1979 to 12.7 million in 1985, and thereafter more or less stabilized at an average of 12.4 million RVD's per year, varying between 11.6 million and 13.3 million per year until 1993.

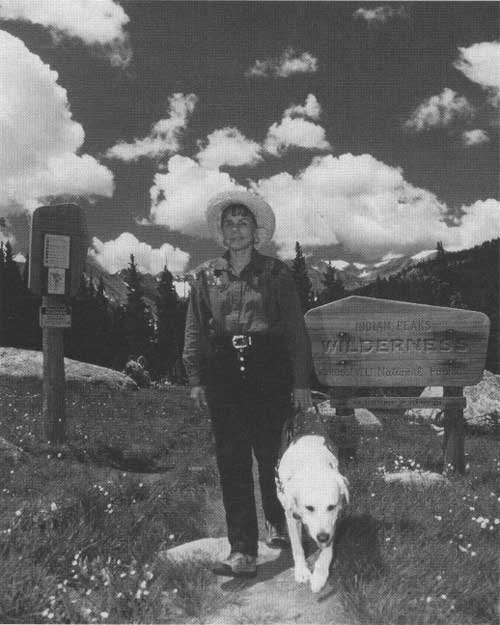

|

| Hiking along a trail in the Indian Peaks Wilderness on the Arapaho-Roosevelt National Forest, Colorado, 1996. (USDA Forest Service Photo. Taken by Tom Iraci.) |

Management of Wilderness

The rapid expansion of the national forest wilderness acreage and units, along with continued growth in visitor use, particularly in the early 1980's, created a huge new workload to develop action plans and implementation schedules for nearly 300 new wilderness units covering almost 20 million acres. These plans and schedules were designed to ensure quality use and management of wilderness areas in ways that would maintain their quality and character. Wilderness managers' and researchers' knowledge and experience, available technology, and public involvement were used to determine the carrying capacity of the various wilderness units. Monitoring tools and techniques likewise needed to be identified, developed, and implemented to protect the wilderness from unacceptable changes. Wilderness plans also included standards and guidelines for recreation use, wilderness education, trail planning and maintenance, grazing use, fire management, motorized and mechanical equipment use, and other aspects of use and protection specific to each wilderness unit (USDI/USDA 1981-1989).

To handle the expanding workload, wilderness planning and management staffing increased slowly from 174 FTE's in 1979 to 196 FTE's by 1983, and then rapidly doubled to 386 FTE's by 1994 (USDA Forest Service 1994f). By 1994, action plans had been completed for all 397 national forest wilderness units (Thomas 1994).

In 1983, the Forest Service convened a National Wilderness Management Workshop at the University of Idaho. This workshop produced a national guide to provide consistency and direction for improving wilderness management practices — Wilderness Management: A Five-Year Action Program. The workshop was a cooperative effort of citizens, organizations, research and education institutions, State agencies, commercial recreation interests, and others who had a stake in wilderness management. The guidelines developed by the workshop emphasized enlisting the cooperation of wilderness users and interests to improve wilderness management practices.

The general Forest Service management goal for wilderness is to provide for scientific, scenic, educational, conservation, historical, recreational, and other uses consistent with sustaining the natural conditions of the wilderness resource and protecting such wilderness characteristics as solitude and unconfined opportunities for recreation and experiencing natural resources in their primeval state. National forest management activities to protect the wilderness include educating users on wilderness benefits and how to protect them, enforcing regulations established to protect wilderness, rehabilitating damaged areas, maintaining inventory data for wilderness uses and resource conditions, preparing and implementing plans for protecting wilderness quality for the use and appreciation of future generations.

Wilderness Management: 1980-1986

Due to the strong emphasis on recreation use through the 1980's, the actual management of wilderness continued to focus on managing people and their impacts. The greatest challenge was to provide for visitor use while protecting wilderness values and allowing natural ecological processes such as wild\fire to operate freely. Teaching wilderness users about the nature of wilderness and how they could use it and enjoy it without degrading its quality was the principal national forest strategy — educating wilderness users rather than regulating them to protect wilderness quality. It was this "people approach to wilderness management" that generally increased visitors' awareness and sensitivity and persuaded them to care more about the ways that they used and enjoyed the wilderness. National forest managers encouraged and received substantial assistance in their educational efforts from wilderness interest groups, outdoor writers, and outdoor equipment suppliers. National forest wilderness managers also depended increasingly upon volunteers to accomplish the annual workload. Wilderness volunteers grew from less than 100 person-years in 1980 to 178 person-years in 1986, when visitor use began to level off (USDA Forest Service 1981-1987).

Visitors concentrating at the more attractive sites and desirable wilderness locations continued to be a problem. This impacted not only visitor solitude, but also wilderness character and wilderness resources. Such visitor impacts on wilderness have always been highly localized — near trails, streams, lakes, and other forest attractions and the heavily used popular campsites often located near such attractions. The wilderness permit system was a valuable tool for limiting and dispersing such heavy use. In the early 1980's, the Forest Service established an approach called "limits of acceptable change" (LAC) to assess when and where to impose use restrictions. Research began to provide information about site durability and user threshold levels beyond which user impacts would become substantial and difficult to reverse. Such studies helped wilderness managers decide where to encourage camping and other onsite uses and where to discourage them.

The identification of 13 national forests in 1994 as "urban national forests" where urban values, demands, and related uses had become dominant illustrated the intensifying use of wilderness areas observed throughout the 1980's. These forests included the Arapaho-Roosevelt and Pike-San Isabel in Colorado; the Angeles, Cleveland, Los Padres, and San Bernardino in California; the Mt. Baker-Snoqualmie and the Gifford Pinchot in Washington State; the Mt. Hood in Oregon; the Tonto in Arizona; the Wasatch-Cache-Uinta in Utah, Wyoming, and Idaho; the White Mountain in New Hampshire; and the Chatahooche-Oconee in Georgia. These 13 forests included almost 4 million acres of national forest wilderness — more than 10 percent of all national forest wilderness — and were located within 1 hour's travel time of a million or more people. The management environment on these forests as a whole was defined as chaotic, as the managers strived to respond to the expectations of the urban user group while protecting wilderness ecosystems. Urban users placed extremely heavy demands for immediate access to wilderness as well as to highly developed recreation areas, recreational waters, resource education, fire protection, firearm shooting areas, and law enforcement. In 1994, these 13 forests provided 82 million RVD's of use, including wilderness visits — more than a quarter of the total national forest RVD use of 330 million (USDA Forest Service Urban Forest Supervisors 1994).

Despite the growing management effort, reported wilderness violation incidents grew from about 600 per year in 1980 to 1,650 in 1986, and continued to increase thereafter. Most violations were illegal use of motorized vehicles and equipment. Other violations included illegal outfitting and guiding, artifact and fuelwood thefts, camping and pet violations, cultivation of marijuana, destruction of Federal property, failure to abide by permit terms, and vandalism (primarily theft and damage to visitor vehicles at trailheads). Search and rescue missions remained more or less stable at about 300 per year. Fatalities ranged between 30 and 50. The number of serious injuries was much greater. Wilderness managers continued to be highly responsive to search and rescue requests in such emergency situations, even though it was evident that many emergency incidents and occasions of lost wilderness users could have been avoided had the visitors been properly informed or better prepared for wilderness challenges. The public, however, came to expect immediate action, such as helicopter lift-outs or rescue, which intruded into the wilderness environment and the wilderness experience of other wilderness users (USDA Forest Service 1981-1987).

Renewed Efforts To Upgrade Wilderness Management: 1987-1995

In the late 1980's, both the Forest Service and outside wilderness interests became aware that a number of factors were contributing to an inconsistent wilderness management philosophy and shortfalls in wilderness management. Ambiguities in wilderness legislation that permitted nonconforming uses, such as mining and grazing, and wilderness boundaries that were legislatively located next to areas of intensive development were two important sources of such inconsistency. Managers were sometimes uncertain about how such situations should be managed. Most managers were trained or practiced in production objectives, but were not schooled or skilled in a wilderness management philosophy, which was akin to preservation. Most focused their attention on managing wilderness for permitted recreation uses and were responsive to the growing demand for increased wilderness use. Many wilderness managers and users alike lacked a common understanding about what constituted a quality wilderness experience. But there was also a corresponding lack of services and opportunities for acquiring such understanding other than through an extended wilderness experience itself. Limited funding and staffing tended to lead to low priorities for wilderness management and the use of "least cost" or "shortcut" technology to solve wilderness management problems. Different interpretations of wilderness laws among managers, wilderness organization leaders, and politicians likewise contributed to the uncertainty and ambiguity of the wilderness management philosophy (USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Region 1989).

To gain a common understanding, acceptance, and support for a consistent wilderness management philosophy and to encourage wilderness managers to apply it on the ground, the Rocky Mountain Region's regional forester encouraged a wilderness philosophy for the region. He enlisted experienced regional wilderness managers and the help of many people with a longstanding interest in and practical knowledge about wilderness — and their organizations, including the American Wilderness Alliance, the Colorado Mountain Club, the Colorado Open Space Council, the National Audubon Society, the University of Iowa, and the Wilderness Society. Working together, they produced and published the Rocky Mountain Region statement on wilderness management philosophy. It focused on wilderness values, uses, users, and management guidelines. Most of these have been incorporated into the Forest Service manual and handbooks (USDA Forest Service Rocky Mountain Region 1989).

Congressman Bruce Vento of Minnesota, Chairman of the Subcommittee on National Parks and Public Lands of the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, spearheaded oversight hearings on national forest wilderness management and a stronger thrust for upgrading wilderness management direction and its consistent application. In March 1989, Vento wrote in a letter to the Chief of the Forest Service that the hearing record was almost unanimous that national forest wilderness management was weak and inadequate and leading to a decline in the quality of its wilderness (Vento 1989). His letter identified the major shortcomings documented in the hearing record and provided 14 recommendations on how to improve national forest wilderness management. These recommendations apparently became the basic guidelines for a major update of the National Forest System wilderness management philosophy and standards — improving the understanding and capabilities of wilderness managers and bringing wilderness management to an equal status with the other National Forest System functional management areas. Congressman Vento's recommendations called for the Chief's commitment and leadership in providing training to wilderness managers and other Forest Service employees on the history, philosophy, and value of wilderness; expanding the wilderness ranger staff; establishing a career ladder for wilderness managers; providing performance standards for all line officers responsible for wilderness management; consolidating wilderness areas fragmented by multiple-use unit boundaries; establishing directors of wilderness in the Washington Office and regional offices to give wilderness an emphasis equal to that of other functional resource divisions; establishing a national public education program on the values of wilderness and its proper use to reduce visitor impacts; and expanding wilderness research in cooperation with other Federal agencies. Vento also requested that the Forest Service report to Congress every 5 years on the condition of national forest wilderness and the restoration of degraded areas. His closing guidance advised the Forest Service to request funding to accomplish these recommendations.

In 1989, the Forest Service's Washington Office enunciated its commitment to manage wilderness as an enduring resource in accordance with the following management principles (USDA Forest Service 1987a): manage wilderness as a distinct resource with inseparable parts; manage the use of other resources and activities within wilderness in a manner compatible with the wilderness resource; allow natural processes to operate freely within wilderness; attain the highest level of priority of wilderness character within legal constraints; preserve wilderness air and water quality; produce human values and benefits while preserving wilderness character; preserve outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive, unconfined recreation experience in each wilderness; control and reduce the adverse physical and social impacts of human use in wilderness through education or minimum regulation; favor wilderness-dependent activities when managing wilderness use; exclude the sight, sound, and other tangible evidence of motorized equipment or mechanical transport wherever possible within wilderness; remove existing structures and terminate uses and activities not essential to wilderness management or not provided by law; accomplish necessary wilderness management work with the "minimum tool"; establish specific management objectives, with public involvement, in a management plan for each wilderness; harmonize wilderness and adjacent land management activities; manage wilderness with interdisciplinary scientific skills; and manage special exceptions provided by wilderness legislation (for example, mining, grazing, and access to private lands) with minimum impact in the wilderness resource.

Thus, the problem with wilderness management in the late 1980's was not so much a matter of management objectives and principles, but a lack of consistency in understanding, commitment, and resources for their full implementation. A 1989 study by the U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO) addressed and confirmed these problems in their findings and recommendations (GAO 1989). The GAO report found that the shortfalls and unevenness of wilderness management implementation were generally contributing to some deterioration in wilderness quality and that inadequate funding was a major contributing factor. It also reported that the full extent of the reported deterioration could not be determined because many areas lacked baseline data on wilderness conditions as well as current condition data. Some areas were in relatively good condition, but others often showed deterioration on trails and bridges and around popular camping areas.